Youth Activists 15 Years Later

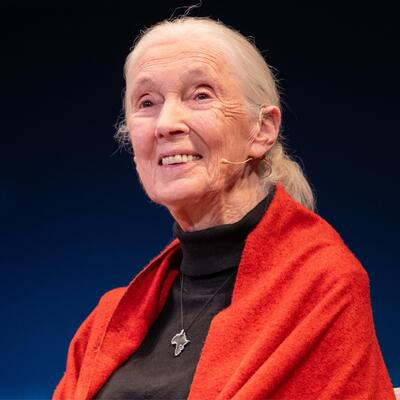

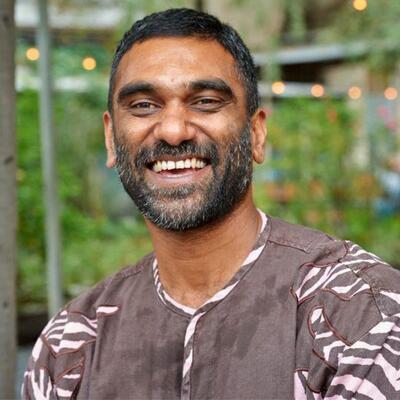

Guests

Alec Loorz

Victoria Loorz

Slater Jewell-Kemker

Kyle Gracey

Abrar Anwar

Summary

From the climate movement’s earliest days, young people have been actively pushing older people in power to own up to their failings and work for a better future. But activists who spend their youth fighting to change big systems frequently feel burdened by unrealistic expectations. Some succumb to depression and burnout.

Alec Loorz was a celebrated youth climate activist years before anyone heard of Greta Thunberg. Starting from the time he was 12 years old, he dedicated his life to traveling all across the country educating other young people on the climate crisis and inspiring them to take action through his organization, Kids vs. Global Warming. But at the age of 18, he fell into a deep depression and withdrew from the movement.

“It was just exhausting and so difficult … and the cynicism about the movement was part of it too,” he says. So he decided to try something else. “And for me what that looked like was just stepping aside, taking a big step back.”

His story is not uncommon. Many activists burn out, frustrated by participating in actions that very rarely lead to meaningful and lasting change. The emotional cost of seeing so little payoff for years spent fighting can be agonizing at any age, but perhaps more so for young people who put so much of themselves into the effort.

Slater Jewell-Kemker was another young climate activist who documented the work of her peers for a decade in her film, “Youth Unstoppable.” She says being a youth activist at international climate negotiations often felt limited and dehumanizing, especially as the real impacts of climate disruption grow greater each year.

“It feels like the people in charge who have the power to make real change are in a completely different reality. And it's very difficult. It's very hard. And then you come home and most people have never heard of a COP [Conference of Parties] or the UN climate change conferences and you feel like you're in this weird sense of, ‘am I just screaming at a wall? Am I screaming into the void? Like, can no one else see this? Am I insane?’”

She says only a fraction of her peers avoided burnout and remained involved in climate action. Like Alec Loorz, who is her now husband, she decided to step back from direct activism. The two of them now live in rural Ontario, focused on permaculture and sustainable living close to the land.

“I look back at it now and there is a part of me that is angry that the narrative encouraged me as a child to believe that I could fix the world's problems.”

Still, some youth climate activists manage to remain involved while keeping despair at bay. Abrar Anwar says becoming a father helped him stay focused.

“Giving up … is not an option. The next generation is here. We were the youth climate activists. There is a new generation of them now. We've got kids of our own that are inheriting the world next.”

Episode Highlights

3:30 Alec Loorz on feeling a sense of calling to the climate crisis

9:00 Alec Loorz on jumping over dread straight into action

12:45 Alec Loorz on hitting burnout and depression

15:31 Alec Loorz on reconnecting with nature and the wild

18:00 Victoria Loorz on supporting her son’s passion for climate activism

24:30 Alec Loorz on our current place in the climate crisis

33:30 Slater Jewell-Kemker on youth not being taken seriously at G8 summit

38:40 Slater Jewell-Kemker on experiencing burnout and anger at climate inactio

48:10 Abrar Anwar looking back on his youth climate activism

54:00 Kyle Gracey looking back on his youth climate activism

59:00 Advice for today’s youth climate activists

Resources From This Episode (2)

Full Transcript

Note: Transcripts are generated using a combination of automated software and human transcribers and may contain errors. Please check the actual audio before quoting it.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One, I’m Greg Dalton.

Ariana Brocious: And I’m Ariana Brocious.

Greg Dalton: Human-caused climate disruption is a collective crisis, and one that compounds the longer we don’t address the root causes of it.

Ariana Brocious: But for so long we’ve thought of it as a future problem – one that the next generation will solve.

Greg Dalton: I’ve been covering climate for close to two decades and it’s only the fires, floods and heat of the last few years that have caused climate to be perceived as a problem now, not off in the future.

Ariana Brocious: And let’s face it– laying our hope for climate solutions at the feet of young people is unrealistic, and completely unfair.

Greg Dalton: From its earliest days, children and youth have been active in the climate movement, pushing older people in positions of power to admit they caused the problem and work to fix it.

Ariana Brocious: No one has made this point better than young activist Greta Thunberg, who calls out older generations for failing hers and not owning up to the problem they created, while actively worsening the climate crisis through their inaction.

Greg Dalton: Greta’s frank, impassioned critiques and weekly climate protests made her famous. She was preceded by other youth activists like Slater Jewell-Kemker.

Slater Jewell-Kemker: We need to address, as human beings, our sense of responsibility. And we need to address our selfishness. We need to rethink how we actually live and engage with each other and live with this planet because this is how we've gotten into this monumental problem.

Greg Dalton: As we’ll hear about on today’s show, years of tireless effort fighting for change frequently leads to unrealistic expectations, depression and burnout.

Slater Jewell-Kemker: I look back at it now and there is a part of me that is angry that the narrative encouraged me as a child to believe that I could fix the world's problems.

Greg Dalton: Alec Loorz was a celebrated youth climate activist years before anyone heard of Greta Thunberg, starting from the time he was 12 years old. He dedicated his life to traveling all across the United States educating young people on the climate crisis and inspiring them to take action through his organization, Kids vs. Global Warming. But at the age of 18, he fell into a deep depression and withdrew from the movement.

Ariana Brocious: His story is not uncommon. So many activists have burned out along the way, frustrated by participating in actions that very rarely lead to meaningful and lasting change. The emotional cost of seeing so little payoff for years spent fighting can be agonizing at any age, but perhaps more for young people who put so much of themselves into the effort. That said, some youth activists developed strategies for pushing through the burnout – or avoiding it altogether. We’ll talk to a couple of them later in the show.

Greg Dalton: I met Alec Loorz in 2011, when I interviewed him on the Climate One stage. I often wondered what had happened to him after he dropped out of the public eye. So I looked him up and asked him to come back on the program to share the journey he’s been on since that time, and how he views the climate movement today.

Greg Dalton: So Alec, thanks for coming back. When you were 12 years old, you watched An Inconvenient Truth with your mom. Of course, you are both profoundly impacted. She went up to bed. What happened for you?

Alec Loorz: Well, I was blown away. I watched the whole movie again and all the special features and everything. I have never felt something like that where I felt almost like a sense of calling to participate in raising awareness around this issue. And I felt the need to communicate with young people because we are the ones most affected. I do still say “we” even though I’m almost 30. But that was my initial spark. I saw the movie, ended up doing more research. Started getting invited to speak at events and it kind of took off that was when I was 12. By the time I was 14 I was trained by Al Gore's program to give a version of his slideshow. The youngest person ever at that point which that title is now been usurped several times which I'm very glad about. And then, yeah, through my teens I had this really crazy lifestyle of traveling and speaking at conferences and doing interviews and all of this stuff which was not what I expected. I didn't start out trying to be a well-known public speaker or anything. I just wanted to share the news with members of my generation.

Greg Dalton: Well, you had a calling after watching the movie you kind of launched into this. And at the age of 12 you did become something of a rock star in a then very small climate movement. Here's a clip of you at age 13.

Alec Loorz: I went to a big environmental conference. And while everyone was listening to all these important people speak, they set up a youth pit for all the youth to go. But that’s not what we want, is it? It’s not enough to be saying, “Yay, let’s ride bikes and change lightbulbs.” No. We got to be in there with everyone else.

Greg Dalton: What it’s like to hear your 12-year-old self today?

Alec Loorz: Man, it’s a bit of a trip. That was early, that was one of my first big speeches. And it’s wild because I still agree with that point. Everyone wants like a top 10 list of what are the simple actions we can take to stop global warming, and it's never gonna be that simple. It’s even a tactic of the fossil fuel industry to put the onus on consumers saying that it's our consumption that’s problem. When really our entire society is addicted to fossil fuels at every scale. And going to be worse and worse for us the longer we take to actually start easing away from that.

Greg Dalton: Most 12-year-olds don't build their own PowerPoints and take to the national stage as you did. What was driving you then and what kept you going during those years when many people are just figuring out their identity doing school.

Alec Loorz: Yeah. I mean it definitely was interesting to be engaged in this through my adolescence. I think it sort of took its toll on the way my identity was developing. And at the same time, I did it because I felt like I needed to, almost, that there was a need within the world for people to be having this conversation and for a young person to be the one bringing the science back again. And I really, I guess I will go back to that sense of calling. It’s something that stuck with me throughout the entire time and I still feel that, and that’s not something where I'm trying to say that I specifically have a calling to engage in, the solution to climate change, or whatever. And my point is that everyone is called to participate in this transition in some way in their own way. And that feeling is powerful. It’s something where I just felt like I couldn't not do something. And still feel like that. I haven't quite been out there on stage in at least 10 years but my activism has taken a different form.

Greg Dalton: And we’ll get to that. But that level of notoriety and fame, and this is for people, and remember, this is kind of social media was in a very different place at that time. And a lot of, you know, child actors, they get famous young, they have real difficulty navigating beyond that like young cute phase of their life and adolescence and what’s next. And what was it like for you to kind of navigate that notoriety?

Alec Loorz: It was difficult. Especially in my later teens by the I was 17, 18 I started feeling a sense of like there was a rift within my identity. There was the version of me that went on stage and spoke to an audience and was the climate change kid. And then I felt like my real self was something else that people didn’t see and I wasn't invited to share on stage. And I would like, post things about music on my Facebook and get people saying, hey, what are you doing posting about music? This is not important. You’re a climate change kid.

Greg Dalton: They wanted you to be a certain way, right?

Alec Loorz: Exactly.

Greg Dalton: Expectations of you that they put on you.

Alec Loorz: For sure. And I think that even taps into our culture’s obsession with the hero's journey as an archetype of story, where a single individual hero goes out and discovers something and brings it back and is a hero. I think the culture is shifting away from that. I don't believe that that is the predominant myth for us right now. Or at least it's falling apart and something else is emerging, which has to do with collectivity. The fact that we’re all in this together. It's not ever going to be one person coming to save the world that we have to save the world together. We have to work towards that. Some of the articles written about me back in the day were very much just sort of like he's the next Al Gore. He's going to save us. Which my ego loved to hear but at a certain point it started feeling like, that’s not what this is about.

Greg Dalton: That’s got to be quite a burden to have that trust on you. you preceded Greta by a decade and she put it right back. Like, no, no, don’t put that on me. You boomers, you know, right back at you. When you and I last talked you were 16. You said then that when you were 12 you jumped right into action that dread and despair of climate was just starting to hit you. Let’s listen back to that moment from 12 years ago.

Alec Loorz: When I first heard about climate change when I first heard about this stuff, I just went straight to kind of doing something about it and taking action. And I skipped over despair and denial and stuff. And it’s just kind of taken until the last couple months to kind of hit that space and been struggling with it a little bit.

Greg Dalton: So what was that going on? What was your struggle then?

Alec Loorz: Yeah, last couple of months that is interesting to hear. 16. I think that was the point when I started maybe becoming a little bit cynical about the tactics of the mainstream climate movement. And I’d only been engaged for several years but just talking to people who’d been part of this movement for decades leading up to then. And just this realization of like my god what are we doing we’re trying the same tactics over and over and over again expecting different results. And at the same time, I realize that it's, what else are we going to do? i think a lot of people within the climate space know that continuing to do marches and writing petitions and writing a letter to your congressmen and stuff it’s like, if that was going to work it would have worked by now.

Greg Dalton: Sure. So, yeah, since we last talked, you know, I’ve learned from Renee Lertzman who’s a psychologist who works on eco-anxiety that people try to push their feelings aside and then act because they feel the urgency of climate. Those feelings don't go away. They just grow and fester and then come back and grab you by the ankles or the throat sometime later. But a lot of people I think what you were talking about there is, you know, don't feel, just jump in, do. Because you know, the planet is, our home is on fire, do something. And some people think that that activity will make the despair go away. But it sounds like it did a little bit for you.

Alec Loorz: I was able to not go there I think for the first several years. Even though I knew how treacherous of a situation it was. I just sort of was able to focus in on okay. Doing what I can and it’s going to be okay. I think definitely in the years since then as I’ve reflected it’s, my perspective now is probably a little bit different. I feel like those emotions are extremely important to express and to work with. And the fact that eco-anxiety is like a term now I think speaks to the fact that so many people are feeling the sense of dread. Especially right now this is a poignant time to be having this conversation because the climate has been in the news this last couple weeks. I’m in Ontario right now and up here in Canada the wildfires have been on another level. 23 million acres have burned this year and the previous record was 13 million acres. And the season really is still picking up steam. So it's clear that the type of stuff that we were warning about 15 years ago are starting to arrive and they will keep getting worse. And this is depressing and scary. And I think we need to be talking about that because it's, we’re going to go just crazy, we're going to lose our sanity if we don’t.

Greg Dalton: And by the time you are 18 you wanted a new identity. You said you started to kind of get cynical about the movement. You got depressed that progress wasn't happening, same tactics being tried. You moved to a new school in British Columbia. Tell us about that kind to step away and reinvent yourself.

Alec Loorz: Yeah, I reached a point when I was 18, where I was kind of just done with that world. It was just exhausting and so difficult for my internal self to be mostly just the travel was so intense. Certain months, I was traveling for three weeks out of the month. There was one Earth Day where I spoke in 11 different cities. Took a flight in between each one within a single week. And there are always film crews coming into our house and just sort of always another event to prepare for. So that was part of it and the cynicism about the movement was part of it too. This sort of sense of okay this isn’t working I don't know if it's worth trying to convince everyone else that we should try something else. So I'm gonna just try something else. And for me what that looked like was just stepping aside taking a big step back. I’ve moved to Canada, went to school in BC. made a new Facebook page that I invited new friends to and didn't mention anything about my climate background. I felt wounded by that. And so I kind of just wanted to let it go.

Greg Dalton: It’s like you shedded a skin.

Alec Loorz: Yeah, a little bit. And that became its own sort of difficulty of just connecting with friends and then only like never telling them about the thing. And someone would randomly like come across an old TEDx talk that I did and be like, what you did this? And just this feeling of like that sense of calling never actually went away. The feeling that I needed to do something about this maybe even intensified. And that sort of came to a head in 2014 after I’ve been at that school for two years. The campus was up in the mountains in British Columbia, north of Vancouver, surrounded by like old-growth forests with a river running through and waterfall and just gorgeous. And that spring, 2014, the gravel company that owned the land came in and started clearcutting the forest in a really brutal way. And like I went out there and watched it and was just heartbroken. And just as bad was the fact that none of the other people at the school really seemed to care that much. There wasn't really any sort of a sense that this wasn't okay. Well for me it was like gut wrenchingly not okay. And just the realization that like my God, now that I've witnessed it I could visualize so much more vividly what's going on in the Amazon, what’s going on throughout Canada. The last remaining forests are being cut for profit. So anyway, that was really intense. That sort of one of the things that kicked off my summer of the deepest depression. I sort of ended up taking another step back that year. Went and traveled across the country, worked on organic farms as a way to just connect with the land. And that ended up becoming my main focus. By 2016, I settled in Olympia, Washington. Over the next couple years, I started spending more and more time with shorelines and parks and places that were wild and alive. In 2018 I discovered a stretch of shoreline in Olympia, Washington that I literally fell in love with. I went out there with my cameras doing time-lapse photography, and I would be I would stay out there for eight hours straight or 12 hours some days. I would go early in the morning and stay till dusk, time-lapsing and writing and being there and witnessing birds and animals and watching the tide lower and rise. And had some really significant encounters with wild creatures that I'm working on writing out the stories. Because my sense throughout that whole time was that it's not just for me, I'm not just trying to go and have fun at a pretty place. This is an act of reconnecting with the wildness that has been so devastated by human civilization. And trying to learn how to listen how to hear those voices. How to see these places of being so inhabit them as alive and intelligent and worthy of being valued. And even entering into conversation with. They don't speak in words but they're still speaking.

Greg Dalton: So nature healed you. You connected with nature and that healed you.

Alec Loorz: Yes. And I deeply believe that that is the only way we are going to get out of this mess is by returning to the greater world. And realizing that all the answers are out there. The earth knows how to stay in balance. We just need to find a way to align with that balance.

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation with youth climate activists. If you missed a previous episode, or want to hear more of Climate One’s empowering conversations, subscribe to our podcast wherever you get your pods.

FOR POD: Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. You can do it right now on your device. You can also help by sending a link to this episode to a friend. On our new website you can create and share playlists focused on topics including food, energy, EVs, activism.

Coming up, Alec Loorz on the value of connection he’s learned living close to nature and how it applies to the climate crisis:

Alec Loorz: Something that's giving me a lot of hope for the future is the idea of permaculture the idea that we can build a human presence that is enduring and that is integrated with the wider landscape

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. Youth climate activist Alec Loorz wasn’t alone in his efforts; he had his mother, Victoria Loorz, with him the whole way. She recalls how passionate her son became after watching An Inconvenient Truth.

Victoria Loorz: The next day he was on fire. He had built his own little presentation. He was gonna go to his class. He’s in sixth, seventh grade. And he was gonna tell them we’re gonna stop global warming.

Greg Dalton: Victoria supported her son’s conviction. She ended up quitting her corporate job to travel with him, handling organizing and fundraising while he gave his climate presentations. They did that full time for seven years.

Victoria Loorz: And parents would ask me like how did you get your kid to do this? I’m like you obviously don't have a teenager because you don't get teenagers to do things like you support what they are already passionate about. And so it was his passion that I was supporting all along.

Greg Dalton: They had to navigate the stardom and the pressure that came with it. Which could be tough for a teenager.

Victoria Loorz: You know, and sometimes his ego would get in the way and we talk about it and go, you know, this isn’t about you. And he got that.

Greg Dalton: Victoria recalls some leaders tried to protect her son and other youth activists from the full picture of the climate emergency, even as they welcomed their role in the movement. During the Earth Day 40th anniversary celebration on the National Mall, she was backstage, and overheard three people talking, including climate scientist Jim Hansen and Bobby Kennedy Jr. They were discussing how the planet had passed a critical tipping point.

Victoria Loorz: And as they were talking about it Alec walked up and all three of them stopped talking. And you know change the subject completely waited till Alec was gone and then I heard them, you know, just kind of say the young people, you know, they were protecting him from what is real. And I understand that, wanting to do that, I understand that as a parent wanting to protect ourselves, our own hearts, our children from the reality that is coming that is here that we are in. But I'm not sure I'm not sure how helpful that is.

Greg Dalton: Along the way Victoria and Alec formed an organization to help inspire and activate more youth in the climate movement, youth like the young Swede Greta Thunberg, who rose to prominence years later by calling out hypocrisy and inaction at the UN.

Greta Thunberg: This is all wrong… I shouldn’t be up here, I should be back in school, on the other side of the ocean. Yet you all come to us young people for hope. How dare you! You have stolen my dreams and my childhood with your empty words and yet I’m one of the lucky ones. People are suffering, people are dying, entire ecosystems are collapsing. We are in the middle of a mass extinction and all you can talk about is money and fairy tales of eternal economic growth. How dare you!

Victoria Loorz: Alec was never like Greta, where she’ll just name it and just say you know you guys screwed up and we’re stuck with it. Like he would never say that. That’s just not his heart. His heart is much more collaborative and understanding where people are coming from.

Greg Dalton: But those same feelings resonated for Alec, Victoria says, after he started to become disillusioned with the lack of progress on climate and the scale of the crisis.

Victoria Loorz: When he went to Iceland and actually saw how much the glaciers had receded. He could feel it in his body and the grief began. That was really I think a turning point for him when he could actually feel it and it wasn't just a message.

Greg Dalton: Victoria went on to found the Center for Wild Spirituality and write a book entitled, Church of the Wild: How Nature Invites Us into the Sacred. She has this advice for parents of other youth activists:

Victoria Loorz: I would say listen, honor them, almost makes me cry. They know why they're here. They know this is important. You can support them. You know diminishing this doesn't help. Exaggerating it doesn't help. Giving them ways to be active, you know, learning from them in a way that they're closer to the earth they haven't forgotten as much as we have. So that's what I would say, be present with them. They're going to need you.

Greg Dalton: In talking with adult Alec Loorz, I asked him if he felt any guilt after stepping back from the climate movement when he was younger.

Alec Loorz: A little bit. It’s sort of complicated within myself because I was just so ready to be done with it when I initially stepped back. But I guess you could call it guilt. There's this sense that started building of like the longer that I stayed away it sort of is like. Yeah, I guess there was a bit of a disappointment in myself. And at the same time there was a sense of I'm still searching for what the actual answers are. And I haven’t actually stepped back really, I’ve stepped back from public speaking and doing interviews and stuff. But it's still almost obsessively what I think about all the time is climate change.

Greg Dalton: Do you miss this public spotlight in any way?

Alec Loorz: I don't miss being put on a pedestal and talked about as the hero. What I do miss is being on stage speaking to an audience who is vibing with what I'm saying. To feel that sense of connection with people who are getting something for the first time that I recently got for the first time. And just being able to share it with people and feeling that connection with people in the audience.

Greg Dalton: When you were 12 the world was on track for maybe five or 6° of Celsius of warming. You are really affected by NASA scientist James Hansen saying that we had only five years to make significant progress. And a lot of progress has been made. We’re now on track for 2 1/2 maybe more degrees of warming since the Industrial Revolution. Still bad but not as bad as it was, say, a decade ago. How do you think about the progress that has been made, the good news?

Alec Loorz: Yeah, it is good news. I'm trying to hold back my cynicism. I don't know if I truly believe that we’re on track for 2 1/2 to 3°C. But even if we are, that’s still a really scary world. And I think we have to be prepared for the types of weather disasters that we've been seeing just to intensify and become more common and more prolonged and more intense.But I am trying to find a way to hold both, of feeling the sense of progress is being made. The right types of conversations are happening at a high level at least the beginning stages of those conversations. And there does seem to be a commitment within countries to actually address this problem. I don't know if the actual tactics that are being discussed are actually going to fully get us out of this mess. And it's also one thing to commit to something and it's a whole other thing to actually do it. Nations have been committing to climate targets for at least 20 years and consistently not reaching them. So something still has to kick into gear at that higher political level. And probably my perspective now is that we shouldn't wait until the politicians and UN people figure this out for us, that it takes addressing this in all of our own ways.

Greg Dalton: And so how do you describe your life now?

Alec Loorz: Well at this point I'm living on a former farm in southern Ontario. In 2021 I moved out here from Washington state to be with Slater Jewell-Kemker, who is now my wife. We got married last year. She was involved in the climate movement back when I was and we almost met so many times back in the day, but we only connected in 2019. So we’ve been living together for the last two years and we like planted a food forest with some friends who live close by. We've got probably 20 different garden spaces doing a lot of work generating the soil, building up biomass. I think as I’ve learned more agriculture is a huge part of the difficulty of the situation we’re in. I think the longer that we stick to the modern sort of monocrop industrial agriculture the more difficult it’s gonna be to actually feed everyone properly. And I think so many people are longing to return to the land in this way to grow our own food, to make our own energy, to be in community. So that's what we’re striving for here. And actually something that's giving me a lot of hope for the future is the idea of permaculture, the idea that we can build a human presence that is enduring and that is integrated with the wider landscape rather than making a farm by clearing away what's there and planting a bunch of corn. We’re past the phase of individual people being the solution. And I think it doesn't have to be the other extreme of like mass movement type stuff. I do still think there's a space for that especially if it can be coordinated in a higher-level way rather than like this group is gonna do a march and then it’s over. This group does a march and then it’s done. Like I think we as a movement need to be having this conversation of how do we integrate our efforts and find like an overarching strategy that is common but then decentralized organizing within that. I think that's the type of thing that’s gonna be really powerful as it’s explored more and more throughout the next few years.

Greg Dalton: Alec Loorz is a climate activist, writer and photographer. I’ve interviewed more than a decade ago when you're 12. Thank you for coming back and sharing your story so candidly and openly and vulnerably, Alec. I think a lot of people can relate. And thank you for sharing that.

Alec Loorz: Well, thank you so much for having me back on. It’s a pleasure.

Greg Dalton: You're listening to a conversation about youth climate activists. This is Climate One. Coming up, how one young person found her place in the climate movement by documenting it:

Slater Jewell-Kemker: Okay, I'm not gonna be the kid necessarily who goes and chains himself to a reactor fence. I'm not gonna be the kid who goes and stages some crazy publicity stunt, but I can be the person who goes and films them because no one was paying attention to kids at that time. No one was taking them seriously. (:22)

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Ariana Brocious: This is Climate One. I’m Ariana Brocious. A powerful way to experience the life of a youth climate activist is to watch the documentary “Youth Unstoppable.” It was produced by Slater Jewell-Kemker, who spent more than a decade filming and documenting the work of youth climate activists while being one herself. Like her now-husband Alec Loorz, Slater stepped away from the movement and has found a new sense of peace investing in her life focused on permaculture and sustainable living in rural Ontario.

Slater Jewell-Kemker: I grew up in Los Angeles, California, and my parents were in the film industry and most of their friends, and the people in our life were involved in media or arts. But with a very specific bent of wanting to make the world a better place. One of our dear friends, Jeannie Meyers, started this organization called the My Hero Project, in the very kind of infancy of the internet cause she wanted her kids to have somewhere to go online that was safe and inspiring and made humanity feel a little bit more worth saving even at that time. And when I was little a friend of ours, Kathy Elden, she was gonna go interview the peace activist Ron Kovic for My Hero. And I went along with my mom and he would only give an interview to me. So I was five years old and holding this camera and he put me on his lap and wheeled me around his apartment and showed me all of his anti-war, pro-peace artworks and, and told me about his experiences and I think it just clicked. Something in my brain clicked at that young age of, oh, this is normal. I can talk to anyone I want. I can ask them questions because it's always no until you ask. And it just felt like that was something that I could do in my life. No one had told me yet that, oh, you're five years old. You can't just go and interview people. So I think that just stuck with me.

Ariana Brocious: So you had an early interest in filmmaking, you had role models in your life that were filmmakers, but why choose to do something documenting climate activists?

Slater Jewell-Kemker: When I was about nine years old, I moved up with my family to a farm in Southern Ontario in Canada and going from a very small house and yard in the valley in Los Angeles to fields and woods and rivers and fireflies and animals. And just this magic sense of wonder really reprogrammed my brain as to what joy was in my life, as to what safety felt. And this made me get more and more interested in the environment because it was something that people were talking about, and writing articles about. And something was going wrong. And through the My Hero Project and my parents and my love of filmmaking and newfound interest in the environment, I was given the opportunity to interview Jean-Michel Cousteau, the son of Jacques Cousteau, the renowned marine biologist. And it was the first time in my life that I spoke to an adult of that level, of that immense wisdom and knowledge and like social standing in the world who fully communicated with me even though I was a kid, even though I wasn't anywhere near his level of knowledge on the subject. He spoke to me as a fellow human being and I felt like my questions to him mattered that he genuinely wanted to interact with me and, and he was so kind and lovely and was really the one who I guess, kind of inspired me to go on this journey. He literally passed me a baton and said, it's your job now. And I feel like a lot of kids would say, I maybe wouldn't run with that, maybe wouldn't take it seriously, but I took it very seriously because this person respected me and I respected them, and I felt like I could do something. No one had told me at that point yet that I couldn't. So I started getting more involved and that led me to representing Canada as a youth delegate at the environmental G8 Summit in Japan in 2008.

Ariana Brocious: I'd like to jump in there because there's a moment in your film where you talk about this, where you felt like for the first time kids weren't being taken seriously. And I wanna hear this moment from you. You're 15 years old you’re at the G8 Summit in Japan. This is in 2008.

Slater Jewell-Kemker: It was just really surreal going on the stage cause I felt like we were acts and when they called out the country's names, some of the ministers cheered and stuff and it made me feel like they were just doing that to seem like they were buddy-buddy with the youth of tomorrow. I felt like we were just like the photo op kids.

Ariana Brocious: So what were you feeling in that moment? Explain that feeling of sort of being used as props and was that something that became common as you continued to be a youth climate activist?

Slater Jewell-Kemker: Wow. It's been a, it's been a minute since I've heard that scene. I was 15 years old. I was. I was in this very like small intense period of time where there were about a hundred other young people from around the world, and we were all in this space working together because we were there under the impression that we would be actually collaborating and working with our environmental ministers and with our leaders, and that we would have a say in our own lives that we would be able to actually influence policy and participate in a meaningful way. And some of the stuff that I, when I think about it now that we were talking about even now, is still, I guess, kind of radical but hits right to the point of this climate crisis of this, this existential crisis of, okay, we need to address as human beings, our sense of responsibility. And we need to address our selfishness. We need to rethink how we actually live and engage with each other and, and live with this planet because this is how we've gotten into this monumental problem. This is what is killing people every year and impacting all of our lives. And I was so proud and so inspired by, you know, these other kids who were also my friends. We became such fast friends, my friend Abrar from Bangladesh. And I remember him telling me about how, you know, the floods in his country had been getting worse every year, every year. And that he would be walking through the city streets waist deep or higher in water and how you'd have to just keep going about your day and trying to be okay. And, when this, this moment happened when we were finally were going to be interacting with our ministers, it really was just a photo op. And, you know, at the time, it was the first time of my realizing that, oh, these leaders, these ministers aren't necessarily these gods of morality who want to make everything okay and have our best interests at heart, that they, they too are human beings with flaws and with preconceived notions, and very much only viewed us as eye candy to be used for their benefit. Our words were stripped down. They were made stupid. It was incredibly shocking. I couldn't believe it. And it was only the kids from the G8 countries who actually got to go and interact with their ministers. So Abrar didn't go. My friend from Indonesia didn't go. My friend from Nepal didn't go. So basically all the countries from the global south were not represented or there at all. And it just felt gross to me. And I, I think I've become a little bit more slightly jaded with time because that just kept happening again and again, and again and again. And that was what got me on this journey of this documentary. That's what got me on this journey of being a climate activist, was that I felt like, okay, I'm not gonna be the kid necessarily who goes and, you know, chains himself to a reactor fence. I'm not gonna be the kid who goes and stages some crazy publicity stunt, but I can be the person who goes and filmed them because no one was paying attention to kids at that time. No one was taking them seriously. And, and I felt like, you know, I'm here. I'm willing, I'm gonna just do it.

Ariana Brocious: And that must have been frustrating to feel that sort of lack of power, lack of agency, especially after having this really, you know, profound interaction with Cousteau who had sort of given you the license to pursue question asking and, you know, pursuit of the truth. And I'm wondering how you sort of handled that feeling in the moment, and how much that inspired you to continue this project, of this evolving documentary that you had started.

Slater Jewell-Kemker: Being in that moment in Japan of seeing my new friends who were, even though they were young, were the smartest people in the room, were the most empathetic, kind, and thoughtful people in the room, not being listened to made me extremely angry. At first, I was very depressed and sad, but it then changed into this, this deep anger and this sense of astonishment that these kids who are going to be inheriting this world from our leaders we're not being taken seriously. They weren't even listening to them. And, and I, I took that anger and I, I decided that I needed to go find these other kids who were as impassioned as I was because even though this was such a meaningful experience, pretty much my friend Abrar and I were maybe the, some of the only ones who kept going because it was so unsettling, um, to go and put your heart and soul into something and work so hard and then to not be taken seriously. So many kids just backed away. And that became a cycle that I saw again and again over the years, going to UN climate talks of, of kids going in wholehearted and optimistic and young and happy and not being able to deal with it, with the rejection.

Ariana Brocious: Roughly what percentage would you say of the people within that cohort that you started in, in, with, in the early two thousands? 2000 tens are still activists today.

Slater Jewell-Kemker: Maybe 10%, 15%.

Ariana Brocious: So what does that say, that there's a high rate of burnout?

Slater Jewell-Kemker: It definitely says that there's a high rate of burnout, because when you, when you take a step back and you look at what we're actually dealing with, we've been having these climate change conferences since, you know, the first one took place three days before I was born. And there is this overwhelming sense of urgency and need that has been there, but maybe kicked to the side over the decades. And young people feel it more, I think, than a lot of other parties feel it more than their leaders because this is very much going to be. Impacting their world and their future and their life. Maybe we thought at the time it was going to impact our kids or our grandkids more, and we're now very well aware that it's impacting our lives too. But when you go to these spaces, usually they take place, where all of the leaders and presidents and whatnot are, it's opulent and separate and, and refined and until Paris, all of the youth climate activists and NGOs and other parties were kind of relegated to a random warehouse type environment that was nearby but not too close. And it could be really dehumanizing to be in those spaces, where you're talking about the very fundamentals of life, of what it means to be a human, of what it means to have a community, to have an identity that is being threatened by climate change. Particularly if you're in the global south of having ancestors who are buried in this place and have been for centuries and you won't be able to live there anymore. You'll have to leave. The US or powerful countries coming in with 300 negotiators who can be at every single meeting they wanna be at. And then you have the real stakeholders only have one negotiator cause that's all they can afford and they get easily overwhelmed and can only go to certain ones. And so they aren't really there with the voice. And so it's incredibly depressing to see that year after year without failThe one thing that you can count on is that the climate crisis is getting worse. That we're seeing it more and more, that people are dying, that people are losing their livelihoods. And it feels like the people in charge who have the power to make real change are in a completely different reality. And, it's very difficult. It's very hard. And then you come home and most people have never heard of a COP or the UN climate change conferences and, and you feel like you're in this weird sense of, of like, am I just screaming at a wall? Am I screaming into the void? Like, can no one else see this? Am I insane? It's hard when the people that you love don't necessarily understand what you're doing. It's hard to see how everything that you thought was gonna happen is coming to pass, like some horrible prophecy and people are still coming up with the same ideologies and ideas and ways forward and solutions as they were 10, 15, 20, 30 years ago. That is why there's a huge rate of burnout.

Ariana Brocious: What is your relationship with climate activism now?

Slater Jewell-Kemker: I like to think that I can be a person who can go to the current kind of crop of youth climate activists and, and help them in this, in this hard time and, and remind them of where they came from that it really truly is another example of, of you're able to do what you're doing because of 30 years of other youth climate activists fighting to even be able to be allowed to speak at the UN of, of being in these positions of being the first one to sue the US government of being like all these kids have been fighting this fight. All. Like, I always think of Severn Cullis-Suzuki at 12 years old in 1992 saying in Rio, you know, you tell us to be. Good people and you tell us to pick up after ourselves and to to be nice to other people, and then you do the exactly that. So how can we trust you?

Severn Cullis-Suzuki: You teach us not to fight with others, to work things out. To respect others. To clean up our mess, not to hurt other creatures. To share, not to be greedy. Then why do you go out and do the things you tell us not to do? Do not forget why you are attending these conferences. Who you are doing this for. We are your own children. You are deciding what kind of a world we are growing up in. (:36)

Slater Jewell-Kemker: And I still get that video sent to me like, oh wow, look at this girl. We have to support her. And it's like, this is from 30 years ago. So I think particularly with this documentary and my experiences of way too many burnt out nights of the soul. I feel like I have something to offer when I meet with, when I meet with young people and I meet with kids who are starting out at the same age I did, and, and telling them that it's okay to not be a crazy activist robot, that you are going to be burnt out. When I was a youth climate activist, like I was embarrassed that I felt burnt out. I was embarrassed that I was feeling overwhelmed when really what I should have been doing was, was looking towards my friends and my community and, and talking to them about it. But I felt like, If I took a step away, I was letting down the movement, and then I realized years later that everyone else felt the same way.

Ariana Brocious: What would you say to the younger you in this climate activism space?

Slater Jewell-Kemker: Oh wow. I think if I was to talk to the younger me, one of the most important things that I could say would be to, and I understand saying this, that there is a certain degree of privilege, but to say, to not be so hard on myself. I look back at it now and there is a part of me that is angry that the narrative encouraged me as a child to believe that I could fix the world's problems. And that led to years of struggling with anxiety and depression and perfectionism and wondering, you know, I was putting my all in, why wasn't, why weren't things getting better? I was just not working hard enough. And I grieve for my child self, thinking that I could make it all better. But it is a fallacy to think that a child can fix this problem when we're looking at hundreds of years of systemic injustice and hundreds of years of convenience and consumerism over the health of people in the planet and money. I think there needs to be a lot more kindness. There needs to be a lot more empathy and compassion and listening, and I think we need to acknowledge that maybe we can't win the climate battle the way that we thought we could, the way that we were told that we could. It actually is really meaningful to try to change your community and where you live and where you are, that does make a difference, I think, even if it's just for people to feel like they are maybe living in a better way. I've really come to this place in my life where I feel like that is also important.

Ariana Brocious: Slater Jewell-Kemker is a filmmaker and climate activist. Thank you so much for sharing your story with us on Climate One.

Slater Jewell-Kemker: It's my pleasure. Thank you so much.

Ariana Brocious: Abrar Anwar has experienced the impacts of climate disruption his whole life. A U.S. citizen, he grew up in Bangladesh, a country he describes as unbelievably beautiful but beset by climate-induced severe storms, flooding, tidal surges and more.

Abrar Anwar: I was around 11 or 12 years old and we were going to renew my passport. And the top of our car went underwater as we approached the embassy. We had to get out, we had to wade through almost hip high water and get there. And right next to the U.S. embassy, like say the end of the same street at that time, there was one of the largest slums in the area, and you saw the, like you got to the embassy and you saw all these cars pulling up into this lovely dry space, and you would look around. And you would see people having to pull their belongings, their clothes onto floating pieces of wood and pull it out of the slum uphill towards somewhere where it's drier. (:42)

Ariana Brocious: He got into the climate movement when he was 16, thanks to his involvement in his school’s debate team.

Abrar Anwar: I love to debate. and then there was a debate competition about the environment. and so to prep for this debate, I started doing my research on environmental problems in Bangladesh and what I found shocked and horrified me to my core. From then on, I've been trying to get my voice heard in as many places as possible. And luckily I got to go to the G8 Climate Summit by the time I was almost 18, And actually saw how vast and amazing the youth climate movement was and how dedicated these children were, me being a child myself at the time. And it really gave me hope and pushed me a lot further into becoming a climate activist. So I returned from Japan, very inspired, and I participated in two or three environmental groups here. To help in cleanups and in organizing some more sustainable electricity sources for people in the villages. I then went, uh, and met later in Nepal again, as you saw in the documentary, and that trip inspired me so much. I, I came back and helped my friend start the BU foundation. Which to this day they're heavy into the environmental activism scene here, doing cleanups, road cleanups, tree planting, marches, conferences and everything, and it's entirely youth led. So we phase out as we grow older.

Ariana Brocious: Those of us that live in industrialized wealthy countries know sort of, uh, intellectually that there are people in developing nations that are being hit now, have been hit, first and worst by climate disasters, but it's still another thing to actually see it and then yet another to live it or experience it personally. Because we can't all travel and experience it personally. How, how do you make this crisis real for people who aren't living it the way you are?

Abrar Anwar: We're a more interconnected society today than we were 20 years ago. We saw in the war in Ukraine for the first time that people could go live on the ground in affected areas and show us what their lives are like. And it really woke a lot of people up. People who had no investment or stake started helping out. The climate movement, while it has been leveraging that, I think people in affected areas themselves need to be reaching out more. instead of news channels broadcasting it for their audience, there need to be live streams from our government. There need to be people going into affected areas across the world to show everyone exactly what's happening here. And I think a look at the ground level view of how people are living through these climate disasters, would actually open a lot of other people's eyes.

Ariana Brocious: So you transitioned from climate activism to working in sustainable tech. Do you think you've avoided the burnout that so many of your peers experienced being youth climate activists?

Abrar Anwar: To an extent, yes. Now there are times I, I'm still on the ground, especially because I'm in a country where this kind of disasters are happening regularly, so you can never really count yourself out. But I have definitely seen the burnout from not being heard screaming and speaking to the same policymakers over and over again, the transition from being youth to being an adult and still not being heard, and still fighting in the same movement and not knowing whether you've gained an inch or not, has, it's been a really big burnout on a lot of my friends that I know.

Ariana Brocious: How do you think you avoided that?

Abrar Anwar: I'm not saying I did, but to an extent. Being a father helps 'cause giving up at that point is not an option. The next generation is here. Like we were the youth climate activists. There is a new generation of them now. We've got kids of our own that are inheriting the world next. I think that really helped with me staying focused, but I wouldn't say I've avoided the burnout. I've felt the depression, I've felt the crash. I've seen my friends get arrested and hosed down and taken away by cops and have had to bail some of them out. Or shelter some of them through issues like that. And it's definitely taken a toll. There were days where getting up and working didn't seem like an option. And I have to say maybe it's just taking a deep breath and realizing the world is still incredibly beautiful. Like we have not lost everything we're fighting to save. And there's very beautiful people out there who're trying to make it a better place even now. I think eventually when you see what everyone else is doing, you yourself come back into it and it helps you get back on your feet and go, no, every little bit still does count. Everyone's still trying.

Ariana Brocious: Abrar Anwar is a former youth climate activist and chief technology officer at Rebel Force Tech Solutions.

Greg Dalton: We also spoke to Kyle Gracey, another youth activist highlighted in Slater Jewell-Kemker’s film, “Youth Unstoppable.”

Kyle Gracey: I grew up in southwestern Pennsylvania that was sort of coal country and my family had worked in coal, so that was my first exposure to fossil fuels. But what happened in, I think it was around high school, is they started building wind turbines. In the county next to me. And so those started becoming a thing that people were talking about.

And there were literally places up in the hills in Pennsylvania where you could look one direction and see wind turbines and look behind you and see, uh, coal mines. So it was just this kind of wild visual of sort of the past and the future, uh, of energy. And so around that time I, as I was learning about that, I was also learning about this thing called climate change and just making the connections between those two and getting concerned about it.

Ariana Brocious: I'd like to play a clip, uh, from you. this was filmed at COP 15, the United Nations Climate Negotiations in Copenhagen in 2009, uh, when you were 24.

Kyle Gracey (playback): So right here we’re trying to make sure that a really strong deal comes out of the climate negotiations working with a lot of international youth from around the world in solidarity on the same issues and trying to push for strong climate action. I just want to share the passion of youth and understand that we’re here, we’re ready, we’re involved and we’re just going to get bigger. We’re not just here to say that when we get older, we tried. We think that we can have an impact and we won’t stop until we see the clean energy future that we all want.

Ariana Brocious: So that was nearly 15 years ago, and that particular COP was notoriously a bit of a bust. There was not a strong deal that resulted from those negotiations. What is it like to hear that now?

Kyle Gracey: I think it still tracks for me, you know, the focus on not just being there. Either as a spectator like some people were, or just wanting to try, but actually really being focused and believing that, that we could have an impact. Copenhagen wasn't much of a success, but over the longer period of time, we have had successes. Young people around the world have been successful in moving the needle, uh, on climate action. What I aspired to do at that moment, is what we actually went on to do: to bring the power of young people to the climate negotiations, to influence decision makers, to be more future focused and future generations focused, and to take the entire issue more seriously with their actions and their words than I think they otherwise would have.

Ariana Brocious: You said in that clip. We won't stop until we see the clean energy feature that we want. Did you stop? Did you face burnout?

Kyle Gracey: I did not stop. I continued to work in climate. I still work in climate for at least part of my work today. I didn't personally experience burnout, but I was definitely around lots of folks who went through different periods of burnout. Many of them actually because of Copenhagen. There was a lot of burnout right after Copenhagen. Um, but fortunately I was able to avoid that and keep the momentum going for myself. Long after that.

Ariana Brocious: So tell me what tools and strategies you use to help yourself cope and not maybe experience the same level that some of your peers did.

Kyle Gracey: One is, I tried to be realistic about what the potential outcomes could be. So some of the reasons that people got burned out in Copenhagen was because there was this big narrative built out that it was gonna be the solution to the climate crisis. And so then when that didn't happen and, and when it failed so spectacularly, people were just disillusioned because they had expected that that was gonna be everything. And I never expected it. I expected that it would be at best, Incremental progress and at worst, no progress. Uh, and it was some ended up being somewhere in between. I try to have kind of a healthy level of, of making change, but recognizing that change can take a long time. So that's been the biggest one. And then, you know, just taking care of myself, good self care, you know, eating well, exercising, sleeping, all the things that people talk about for maintaining good resilience. And then just thinking carefully about why I got into this in the first place and being focused on that action, uh, orientation, being focused on creating change and remembering that, that's why I'm here and that I'm planning to do that my whole life. And so if I have to focus on this issue my whole life to get there, that's fine. And if I get there sooner than that, that's great. There's lots of other challenges in the world that I can work on too.

Ariana Brocious:Kyle Gracey is a strategy consultant with Future Matters.

We’ve heard a range of perspectives today from youth climate activists who are now young adults. We asked each of them to share their advice to the youth getting involved in climate today.

Abrar Anwar: My advice would be to be a little more radical than we have been. Try and shake up the system. Governments don't like disruption. Shut down the road in front of your parliament, organize marches, but not just that. Get yourself into positions of power. Aim for places where you can stand toe to toe with lobbyists, with policymakers, with people who are influencing big oil, big energy. Get yourself in a position to be heard and making sure once you're in that position you don't back down and you don't change your opinions based on the pressure you will be feeling from your peers at the time.

Slater Jewell-Kemker: You are going to feel depressed, you are going to feel overwhelmed, and it's okay to take a step back and to heal because you won't be able to continue this work if you just keep pushing on.

Kyle Gracey: My biggest advice is to build community. We are not going to solve any of these problems by ourselves. These are complex, interconnected challenges and we need an entire society of people to do that effectively. So creating connections among other people, working together on this and what we sort of call never worrying alone, never being stuck thinking that you're the only person who's taking on this challenge and recognizing that the reason it feels hard is because it is hard. It's a big complex thing that we're trying to shift in the world, but it can be done. People have changed the world before and young people have changed the world before and they can do it again.

Alec Loorz: Trust your authority as a young person who will be impacted by this crisis. And remember that it's not about you. That this is something collective. We are tapping into something that's bigger than us with having these conversations and engaging in this work.

Ariana Brocious: That was Abrar Anwar, Slater Jewell-Kemker, Kyle Gracey and Alec

Greg Dalton: Climate One’s empowering conversations connect all aspects of the climate emergency. To hear more, subscribe wherever you get your pods. Talking about climate can be hard-- AND it’s critical to address the transitions we need to make in all parts of society. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. You can do it right now on your device. You can also help by sending a link to this episode to a friend. On our new website you can create and share playlists focused on topics including food, energy, EVs, activism. By sharing you can help people have their own deeper climate conversations.

Greg Dalton: Brad Marshland is our senior producer; Our managing director is Jenny Park. Ariana Brocious is co-host, editor and producer. Austin Colón is producer and editor. Megan Biscieglia is our production manager. Wency Shaida [Shey-duh] (rhymes with play) is our development manager, Ben Testani is our communications manager. Our theme music was composed by George Young (and arranged by Matt Willcox). Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.