Rebecca Solnit on Why It’s Not Too Late

Guests

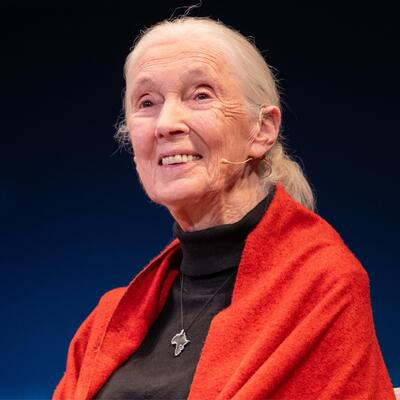

Rebecca Solnit

Summary

Looking at climate devastation while witnessing a lack of political urgency to address the crisis, it can be easy to spiral into a dark place . But a look at the larger picture gives reason to be hopeful, says writer, historian and activist Rebecca Solnit. Solnit has been examining hope and the unpredictability of change for over 20 years. In 2023 she co-edited an anthology called It’s Not Too Late, which serves as a guidebook for changing the climate narrative from despair to possibility.

“I think if I have a superpower, it's slowness. Which means that I see long stretches of time, which lets you see change,” says Solnit. It would have been hard to imagine the technological and societal advancements of 2023 in 1973, but the people of that era working for change paved the way for all the progress since.Solnit says, “It behooves us all to do everything we can towards that better future for human rights, for biodiversity, for 30 by 30, and beyond.” Even if the results of that work aren’t immediate, they contribute to change in the future.

The Green New Deal did not become actual legislation, but it changed how climate policy is discussed on Capitol Hill. In a similar vein, the protests at Standing Rock did not stop the pipeline, but they inspired Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to run for office, beat the third most powerful democrat and become an important voice for climate in congress.

“The idea that we don't have the solutions, that nobody cares, that the media is not covering it are all things that were reasonably true to say 15 or 20 years ago. They're completely inaccurate now,” Solnit says. Renewables are cheaper than they have ever been, cheaper than dirty energy in many places. According to a report by Goldman Sachs,The Inflation Reduction Act is poised to drive $3.3 trillion of investment in clean energy.

“I think there's a lot of people who care, who would like to hope, but who haven't been offered hope.” says Solnit. “We can't make it like we never burned those trillions of tons of fossil fuel and put all that carbon dioxide in the upper atmosphere. But we have tremendous choices in this moment.”

For many, despair is actually a privilege. Sonlit says that for most of us, “we secretly know that we can give up and our lives will still be relatively comfortable and safe.” That kind of thinking, however, ignores the millions of others who do not have the luxury of giving up as their homes are flooded or burned, or when their crops fail. Solnit says, “To let other people die first, other people lose first, other species lose first, I don't think it's ethical. And I think the facts say there's a lot worth fighting for now.”

“A lot of victories look like nothing. The forest wasn't cut down, the toxic incinerator wasn't built in the inner city neighborhood, so the kids didn't get asthma,” says Solnit. But that does not take away from the fact that they are indeed victories. And there are visible victories: Solar energy projects are being implemented so fast – a gigawatt a day – it’s the equivalent of a large nuclear power plant opening every day.

Every action people take to mitigate the climate crisis will matter. And even if the goals that are set aren’t achieved, the closer we get, the better the outcome. Solnit says, “The difference between the best case scenario and the worst case scenario is profound.”

Episode Highlights

2:08 Rebecca Solnit on slowness as a superpower

5:07 Rebecca Solnit on the Green New Deal

12:31 Rebecca Solnit on progressive politics and climate

15:20 Rebecca Solnit on climate defeatists and deniers

18:46 Rebecca Solnit on building empathy

27:24 Rebecca Solnit on Feminism

32:46 Rebecca Solnit on the climate crisis and the democracy crisis

45:38 Rebecca Solnit on changing your mind

Resources From This Episode (4)

Full Transcript

Note: Transcripts are generated using a combination of automated software and human transcribers and may contain errors. Please check the actual audio before quoting it.

Greg Dalton: Climate can feel dark and difficult to deal with both intellectually and emotionally, and I do think there are good things happening. Progress is being made. So we're going to talk about what's going right. I'm Greg Dalton.

Ariana Brocious: I'm Ariana Brocious.

Greg Dalton: And this is Climate One.

Ariana Brocious: On today's show, we're featuring an interview with Rebecca Solnit, a writer, historian, and activist who's been examining the concept of hope and the unpredictability of change in her work for more than 20 years. She's a real voice of hope when it comes to the climate crisis.

Greg Dalton: Right, and she's not Pollyannish. I cycle through ups and downs, and she really lifted me up. For example, she talked about proposed bills such as the Green New Deal and the Standing Rock protests, seen as failures, but they had unanticipated positive consequences. And then there are laws that are enacted that have indirect or knock on consequences that don't get counted in direct impacts. I'm comforted by her wide ranging and long term thinking. I guess you could say, Ariana, I like her math.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, me too. I came away from my conversation with her feeling a bit more upbeat about where we're at in this moment in the climate crisis and what the future holds and how much power we have to change it. In addition to climate optimism, she is a vibrant voice on women's rights. Her 2014 essay, Men Explain Things to Me, has been credited with coining the term mansplaining, which is a cultural phenomenon that I think many of us are familiar with. And mansplaining in particular can be kind of an easy cultural touch point. But the truth is that her work is resonant on all sorts of subjects.

Greg Dalton: I've heard of mansplaining and I've practiced it according to my college age daughter. In 2023, Rebecca co edited an anthology called It's Not Too Late, which is a guidebook for changing the climate narrative from despair to possibility. Thank you. We need that.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, we really need that. I had the opportunity to sit down and talk with Rebecca recently at the Commonwealth Club of California, and we had a nice wide ranging discussion. And we started with talking about her ability to take the long view of things.

Rebecca Solnit: I think if I have a superpower, it's slowness. Which means that I see long stretches of time, which lets you see change. And one thing I run into a lot with climate is people often conflate impossible with unimaginable. Nobody in 1973 could have imagined 2023, but everything good in 2023 is because somebody in 1973 or some past, um, moment fought for it. And I like 1973 because you can see, um, The most mainstream narrative is that the Civil Rights Movement, which means the Black Civil Rights Movement, was really in decline at that point, arguably. Um, you could debate that. But Native, Native, you know, after Alcatraz, and the formation of AIM, et cetera, the Native rights movements were really surging. The women's movement was surging. Gay rights were really beginning to gather force. A disability rights movement was happening. And the environmental movement, which was something really different than the earlier conservation movement. It was also really beginning to do stuff and even the language for thinking about all these things had to be invented. And I know feminism best in some ways. Words like domestic violence and marital rape weren't concepts or terms people had. So you could see they made mistakes, they stumbled, they didn’t know what they were doing, but so much good stuff comes of it. So I feel for 2073, it behooves us all to do everything we can towards that better future for human rights, for biodiversity, for 30 by 30, and beyond, and for the climate, knowing that most of us won't, oh, there are probably some young people, Most of us won't be here in 2073. I don't plan to be. And, um, I think I'd be 112. And, though never say never. You can't see the future, but you can learn the shape of change from the past. And to see it also means seeing indirect consequences and other impacts. A lot of despair, et cetera, comes often from people thinking that if. You know, like if we have, if we make demands of a government on Tuesday and they don't fall to their knees and say they were wrong and we were right and give us everything we asked for by Thursday, then we failed and that's just not how change works, although it's how defeat works.

Ariana Brocious: Right. I think about the Green New Deal, this idea that was, you really popularized, and seen as very kind of far out, you know, uh, extreme in some, in some sense, and then became adopted by leading presidential candidates, you know, and kind of form, put it part of their platforms. We still don't have the Green New Deal, but that has been kind of modified and come into Build Back Better that Biden was trying to get. And then that also failed. But we got the inflation reduction act. So, we're, we're making progress, right?

Rebecca Solnit: Yeah, and to assume that if the Green New Deal didn't pass, it failed, which is again that kind of short sightedness that I, I keep trying to counter, is to fail to see it completely change the conversation. Part of the genius, even of the name, the Green New Deal, is to say taking care of the natural world is a brilliant jobs program. you can see there are green new deals that have been adopted in cities and regions in the United States and elsewhere. And again, even with IRA, you have to measure the indirect consequences, like a huge part of Europe and some other. countries were like, what they're going to pump all this money? We need to pump a bunch of money. And so it's having these kind of like knock on consequences in the same way that standing rock didn't stop a pipeline, but had a number of remarkable other consequences, including inspiring AOC, who was just a bartender and waitress nobody had ever heard of, to run for office, and one of the great upset victories of recent history. Defeat the third most powerful man in the Democratic House to become the youngest woman in Congress ever. And do a lot of amazing stuff. And be maybe one of the great voices of our time.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, I think so.

Rebecca Solnit: Standing Rock inspired her to do that.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah. So a lot has changed since you entered the climate movement or the environmental movement, how do you evaluate the progress that's been made when we look back and we've talked about some of these, you know, the recent bills, but when you look back on maybe the last 20, 15, or even five years, what we've done, and also considering that as there's been progress, there's been continued, um, acceleration of climate impacts. You know, last year was the hottest, this is the hottest year and that keeps happening.

Rebecca Solnit: Thank you for asking me a slowness question, a long term change. I think if you told people where we were with renewables and how powerful and engaged the climate movement is, and how much the public is engaged compared to where we were 10 years ago. I don't know how much people would believe it and I think some of the problems we still have are that people's, a lot of people get this vague understanding and don't get updates. The idea that we don't have the solutions, that nobody cares, that the media is not covering it are all things that were reasonably true to say 15 or 20 years ago. They're completely inaccurate now. And it's also really interesting because there was this period, I think of it as the Al Gore Inconvenient Truth Compact Fluorescent Prius era, I didn't fully realize myself until I read this wonderful book that's a short history of the human use of coal from the very beginning through the industrial revolution to the present. The book came out at the end of the 90s and it said, burning fossil fuel is bad, but we don't really have an alternative. I read this about eight or ten years ago, and it made me think oh my god renewables were not what they are now. We've had an energy revolution and this energy revolution is too slow for most people to have noticed renewables were expensive. They were primitive. They were utterly inadequate to the job, even a little over 10 years ago, let alone at the millennium. So we've had an energy revolution that's incredibly exciting, but only if you can see, um, the arc of change, which is slow and incremental and very wonky. Everything is different. In the early climate movement was polite. It was sort of requesting and kind of trusting governments and corporations to do good things. The idea that we had to fight them, blockade them, call them out, etc. I watched the founding of 350. org and watched it go from a kind of nice, polite organization to a much more radical one.

Ariana Brocious: So people are throwing soup and paint on famous artwork, right?

Rebecca Solnit: When people get all, all outraged about that. I'm like, I saw the impact of the BP blowout in the Gulf of Mexico. Like, you think a little tomato on a sheet of glass is bad? Let me tell you about lighting the ocean on fire and respiratory diseases, the ruination of Vietnamese refugees, livelihoods in the fishing industry, thousands of pelicans coated in oil, and all the kids with asthma here by the Chevron refinery. All the forms. The fact that fossil fuel, every step of the way is poison, and it's political poison as well. It feels like something we're just beginning to recognize. Because we grew up in the, sort of, the age of fossil fuel, or is regnant and triumphant, and it's been completely normalized, and part of our job is to denormalize it.

Greg Dalton: Arianna, I really appreciate her response to your slowness question. There's so much emphasis in the climate conversation on speed and scale, speed and scale, we got to go faster, faster, faster. I think sometimes we overdo it. And there's a saying I forgot where I heard it once, it's like, things are urgent, we better slow down. I just spent a week at a Buddhist monastery with a bunch of climate people where we walked and talked and chewed very slowly. It was very powerful. And these are people who know we need to do a lot fast. So sometimes slowness can be really powerful and in some ways we don't really see in our hyper fast culture.

Ariana Brocious: Right. And the other thing Rebecca says in relation to that is that there's these seeds planted all the time that don't fruit until much later. So you may not think that what we're doing now is that impactful or that the conversation that you had with someone about climate didn't change their mind in that moment, but bit by bit, as we continue to put our energy into this, we do make change and those things unfold and develop over time.

Greg Dalton: We're so conditioned to see like direct immediate cause and consequence. A lot of systems don't work that way.

Ariana Brocious: And we also have to hold the truth that we do need to act fast. That there is a sort of a critical decade ahead of us where a lot of things have to happen and slowing down now will harm us in the future. So we have to sort of be embracing both of those ideas of the need for urgency and also the deliberation and the benefits of a slow thinking approach.

Greg Dalton: When do we go fast and when do we go slow? A lot to think about there. We'll get back to your conversation with Rebecca in a minute. If you missed a previous episode or want to hear more of Climate One's empowering conversations, subscribe to our podcast wherever you listen.

Ariana Brocious: And these conversations are really critical. Help us get more people talking about climate. You can do this by giving us a rating or a review. or recommending our show to a friend.

Greg Dalton: Coming up, privilege can make people complacent – that’s not gonna affect me – or nihilistic – it’s not gonna make a difference – and forget that there are communities suffering now.

Rebecca Solnit: Despair is a luxury because for most of us giving up, at some level we secretly know that we can give up and our lives will still be relatively comfortable and safe.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

This is Climate One. Let’s get back to Ariana’s conversation with author and activist Rebecca Solnit.

Rebecca Solnit: There's a really powerful, pervasive idea in the progressive world that our job is to convert our enemies, that we're little evangelists out there to out debate people who don't agree with us. I wrote an essay for Harper's when I was writing a column there, before it became so conservative again, In Praise of Preaching to the Choir. We have enough people who believe that climate change is real and urgent. that if all of them mobilized, if all of them were fully engaged, we could do everything we need to do. And it's, we don't need to convert our enemies. We need to mobilize our friends. IAnd, um, you know, in preaching to the choir is this dismissive phrase I heard all my life. And it's like, The choir comes to church to sing, to hear some preaching, to gossip on the church steps or the synagogue or mosque steps or whatever. And it's also such a transactional notion of what, what speech is for. I do run into people, sometimes, usually male, sorry, think that words are for either bullying somebody into agreeing with them or doing an information dump. But words are for, there's words of love, words of joy, words of humor, um, words of poetry. Language is how we connect and it's often, and what, what kept me alive as a young woman was really long conversations back in those days of like the phone just rang and you picked it up and it was one of your best and then you talked for two hours. And we reaffirmed that we had value, that we had rights, that each other's experiences were real. You know, as we're being gaslit that, you know, sexual harassment didn't happen in the world, you know, sexism didn't exist and also shut up, and et cetera. So we do a lot with language to reinforce each other, to support each other, to encourage each other. And some of the climate conversation is definitely about info dumping, some of it will be about debating, but a lot of it will be about encouraging – a word a writer friend of mine reminded me a while back means to instill courage.

Ariana Brocious: Good climate news, good environmental news can be slow moving, can be highly technical, and as a result it doesn't necessarily get the same play or coverage or even public understanding as something like a hurricane or a fire. wildfire or things that are much more, um, fast, um, gripping, you know, kind of destructive, bad news. So I think it can be easy for people to read the news and think that we're in a pretty dire situation. Um, how do you think about climate defeatists versus climate deniers?

Rebecca Solnit: I feel like there's concentric circles of climate understanding, and then I feel like I'm making a model of Dante's hell, we'll set that aside. think his ring sort of descended, mine might ascend. Maybe this is purgatory. But I feel like the denialists are just refusing the information, and I think a lot of it is because what the natural world is constantly telling us is everything is connected to everything else, and we all have responsibility towards the whole, which is a very anti rugged individualist, anti free marketeer, um, libertarian thing, so it's ideologically offensive to conservatives. But they're so far over there, they kind of don't matter, and um, but climate defeatists who abound often are also not particularly, they don't deny that climate is real. They often deny that solutions are real, that the movement is real, that coverage is real, that people caring is real. So they have their own amount of denial. There's a kind of depression where you just want to sit in the corner or curl up in fetal position or whatever, but these sort of evangelists of giving up, like the energized ones, I don't fully understand it. But I find that a lot of times that very often that their facts are wrong and that their frameworks about how change works and the nature of power is often wrong, too. And then within that, I think there's a lot of people who care, who would like to hope, but who haven't been offered hope. And then what's really interesting, when you get to the organizers, the scientists, the journalists, the people who are really involved, they're scared, but they're not despondent. They know that this is the decisive decade, that it, that future is what we will make it in the present. There are parameters, of course. We can't make it like we never burned those trillions of tons of fossil fuel and put all that carbon dioxide in the upper atmosphere. But we have tremendous choices in this moment. And the difference between the best case scenario and the worst case scenario is profound. I wrote an essay last year called Despair is a Luxury because for most of us giving up, at some level we secretly know that we can give up and our lives will still be relatively comfortable and safe.

Ariana Brocious: And it's easier to give up,

Rebecca Solnit: Yeah, and so what you're really doing is giving up on behalf of people. You're saying, let those kids starve. Let the, let those, let that ice melt. Let those storms destroy the crops of those people in Central America. Let you know we're you, we, we who are relatively comfortable, safe, affluent, and therefore powerful, I think have no moral right to give up and we're giving up, you know, to let other people die first, other people lose first, other species lose first, I don't think it's ethical, and I think the facts say there's a lot worth fighting for now, and fighting for it is a really good way to live.

Ariana Brocious: So you were describing this idea that giving up for people in the global north, as we just say, you know, there's those of us who live in the wealthier, more privileged parts of the world, and who have also contributed the majority of the emissions that are now contributing to the climate crisis, that giving up by us is essentially, consigning other people to death and now and in the future. So that strikes me as, um, lacking empathy, lacking understanding. So how do we build more empathy, more understanding among, you know, those in the global North?

Rebecca Solnit: One thing that I found fascinating when I finally understood what most human rights and environmental movements do, first of all, is try and make the invisible visible. When I started volunteering with Rainforest Action Network in 1988, people didn't know anything about the Amazon and the role of rainforests in Global Health, etc. I remember actually standing on a corner, um, very near here, and there was this 20 something year old who was very shy and, and, uh, being told by some man that no, the Amazon was not the lungs of the earth. And uh, some guy in a business suit, but whatever.

Ariana Brocious: Mansplaining.

Rebecca Solnit: Yeah. But, you know, and so bringing those stories, connecting people, and then also one of the narratives we really need to dismantle because we have a lot of bad stories about climate too. The fossil fuel industry was very excited about the idea of climate footprints because if we could all worry about our personal virtue, we wouldn't worry about them. And it is our job to worry about them, fight them, and ultimately dismantle them. I'd also suggest that everybody is responsible, but the richest 1 percent of human beings on earth have twice the impact of the poorest 50 percent of people on earth, you know, peasants in Bangladesh are not really causing a lot of climate warming, people with private jets are. So it's also understanding that, you know, we have varying impacts depending, you know, on personal choices and that it's not just a personal responsibility thing. I have 100 percent clean energy at home, which if you're in San Francisco, you can sign up for with Clean Energy SF because somebody else fought to make that an option. I rode my bike today in bike lanes because the San Francisco Bike Coalition fought for bike lanes. Pretty soon, thanks to the movement to stop allowing gas hookups in new construction, you won't have to opt out of having methane pumped into your house. when you phrase it that way, it sounds pretty lurid, doesn't it? You know that houses will be all electric. And um, so we make these changes together and um, and we. make people visible, and we make the benefits of what we're doing visible together. And so much climate work is just making visible what's happening with oceans, what's happening with the global south, what's happening with rainforests, what's happening with impacted communities But also making visible the movement, the solutions and the victories. And I think the left historically is really bad at celebrating victories and the climate movement has a hell of a lot more we, we need to do, but we've accomplished a lot.

Ariana Brocious: So how do we celebrate victories more? Because I think this comes back to the idea that environmental stories, you know, one editor told me once, they ooze, right? They just kind of like incremental things, they go bad slowly, they get better slowly. There's not as much drama. But there's been a lot of environmental or climate victories that are preventing harm.

Rebecca Solnit: Yes.

Ariana Brocious: Rather than achieving a new solar plant or something. So how do we celebrate those?

Rebecca Solnit: A lot of victories look like nothing. The forest wasn't cut down, the toxic incinerator wasn't built in the inner city neighborhood, so the kids didn't get asthma, uh, um, the coal plants, the liquid natural gas export facility wasn't built, etc. So a lot of times if you're looking for victory, it literally looks like nothing, it's a thing that didn't happen. But a lot has happened and is happening. Bill McKibben pointed out the other day, we're implementing solar energy so fast. it's the equivalent of a large nuclear power plant opening every day. One of the great victories climate people often hark back to is the Montreal Treaty to stop the ozone depleting gases, which was actually really successful. And then just in the last few years, there was a major milestone in the recovery of the ozone layer because we had this treaty. And treaties sometimes work. A Lot of it is on the media, which is part of my job and yours. but all of us are storytellers. one of the things that happens at a lot of climate events is people ask what can I do? A lot of what you can do is be informed on climate, including the victories and the possibilities and bring them up in conversation and be equipped to counter defeatism, despair, when it's due to what Thelma and I call bad facts and bad frameworks. Because it's also bad frameworks about how change happens or where power lies, because power also lies in the grassroots. It lies in good ideas, it lies in civil society, it doesn't just lie in elites, which is the story we're often told to make us give up.

Greg Dalton: I love what Rebecca says about defeatism, that it takes a certain amount of privilege to give up. And that people with privilege like you and me have no moral right to give up on the climate challenge.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, it's a privilege to ignore something that doesn’t affect you directly. And I think about the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020 and how this is really an example of showcasing how if you weren’t affected, you could just turn your TV off and give yourself a break - in contrast to people who experience racism and violence in their lives every day; they can not just turn it off. If you live near an oil well or a refinery, it’s affecting your daily life, and it’s a lot harder to ignore those things.

Greg Dalton: And capitalism depends on those sacrifice zones or concentrating harms in certain areas while the benefits go to other places. On a previous Climate One episode, I talked to Leah Thomas, the Founder of Intersectional Environmentalist. She really opened my eyes to how important it is to address multiple systemic problems at once. And this really connects back to what Rebecca Solnit was saying about how easy it is for relatively privileged people to give up. Here’s Leah Thomas:

Leah Thomas: What I hear from a lot of white kind of well-to-do environmentalists is the sentiment of it’s too complicated. I just want to focus on you know, reducing greenhouse gas emissions. But they don't realize the privilege that’s kind of wrapped into that because they’re saying I want my future for my grandkids to be fine, but my present is okay. And to me there are people without clean air and clean water, and that is not complicated and we need solutions to address who is being impacted by that right now.

Ariana Brocious: She puts that so clearly and so powerfully.

Greg Dalton: She does and for decades, the mainstream environmental movement has been mostly white and well off. And because of their limited perspective, solutions hasn’t always gone as far as they needed to.

Leah Thomas: Even though the environmental protection agency was created, Earth Day was created all of these environmental laws and regulations to them may have thought, hey, you know, things are getting better in the 70s and 80s. However, because the movement wasn't intersectional, didn’t really include a lot of low income and people of color then we just see toxic waste sites getting kind of diverted to these vulnerable communities and staying away from wealthier and white neighborhoods. So the problem didn't disappear, it just disappeared for them.

Greg Dalton: And the same way that race and class play a critical role in climate outcomes, so does gender.

Ariana Brocious: And because of society's inequality, women are more vulnerable to the effects of a heated planet.

Greg Dalton: They are the ones often walking distances daily to fetch water, caring for young and elderly. The UN says as climate change drives conflict and declining agricultural production across the world, women and girls face increased vulnerabilities to all forms of gender-based violence, including human trafficking, and child marriage.

Ariana Brocious: That’s so heartbreaking. And gender also impacts how people feel able to participate in climate or other social movements. If you have been systematically ignored, pushed aside or silenced, whether through workplace culture, harassment, or outright violence, you aren’t going to feel safe putting yourself on the line for something.

Greg Dalton: That’s a good point. I hadn’t really thought about that.

Ariana Brocious: WellI think it’s true for all of us that it’s hard to understand what isn’t our lived reality. And what’s really important is that all of these issues are intertwined, and there is no solving the climate crisis without addressing race, class, gender, and other identity issues. Let’s get back to my conversation with Rebecca Solnit.

Rebecca Solnit: The goal really is, and this is a goal of anti racism, um, a lot of other human rights struggles, the goal is a democracy of voices. It's not to shut down. The voices that have historically been heard, but to make them one of many voices to let the voices that haven't been heard happen I worry a little bit because you sometimes get a dismissiveness as though feminism is, either has achieved goals and should shut up and go home. I don't like the idea of generational waves. but it, um, it does feel seismic. There are these seismic ruptures. We had one in the late sixties. We had another one in the eighties. Um, we had one, I think me too, is the consequence of the rupture that really came in 2012. It was kind of bearing the fruit of the changing conversation of surfacing the violence, the abuse, the silencing. So that when those actresses came forward, the ground had been laid for people to hear, believe, and understand in a way they hadn't. It's another model of change working slowly and incrementally. Feminism is a human rights movement. It's a democracy movement. And the short example I can give is how did Bill Cosby and Harvey Weinstein have like Half century long crime sprees of doing horrific things to women. It was about, uh, an autocracy of voices. They were confident that they had more power, more credibility, more control than their victims. I think rape and sexual assault are both enforcements and enactments of that inequality. I can do anything I want to, you have no rights and no voice. Not even the voice to say no, not the voice to testify afterwards. And they literally got away with it in both cases for half a century. And then we got into an era with more democracy of voices. So you can't disconnect the violence against the physical violence from the social violence, the conceptual violence. That's also about, you know, I met a woman from Texas whose mother was one of the first women to sit on juries in Texas. Texas didn't let women sit on juries until the 50s. Which meant if you were a victim, a woman victim, you had to get men to...

Ariana Brocious: Believe you.

Rebecca Solnit: Yeah, which, um, the whole, and we had an entire culture, it wasn't just individual juries or whatever, we had an entire culture that in every way, including blaming Eve, et cetera, portrayed women as subjective, delusional, unreliable, vindictive little hussies, et cetera, and men as somehow having a monopoly on objective truth. And that's impacted climate scientists, that's impacted women politicians, that's impacted women. And it's also kinds of professional spheres. And it's also impacted women saying he's trying to kill me who aren't believed until they turn up dead. And so, because I often, you know, I did not coin the term mansplaining, although I'm often credited with it. So far as I can tell, the essay published in 2008, the title essay, Men Explain Things, to me, inspired it. And I have an entire file at home, I call the Mansplaining Olympic Tryouts. Um, with more than a hundred spectacular examples. The original essay I wrote is about. A nuclear physicist in Livermore telling me, laughing, that one of his neighbors recently ran out of the house naked screaming her husband was trying to kill her. And I looked at him. I said, how do you know he wasn't trying to kill her? And it was terrifying to realize his beliefs were so fixed, the one thing that couldn't occur to him with a naked woman in the middle of the night saying he's trying to kill me is that that he might be trying to kill her.

Ariana Brocious: And she might be telling the truth.

Rebecca Solnit: Yeah, and so the,

Ariana Brocious: you know, so

Rebecca Solnit: you know, so credibility, you know, having language, not just in having words, but living in a society that will listen to them, having credibility, um, consequence, uh, you know, audibility, are survival tools that women didn't have, and you know, I care about climate. I'm totally committed to it. I've kind of retooled my life to, for that to be mostly what I do. But I can't not care about feminism, and they're not all that separate. And feminism is also like my own life story, including family histories of domestic violence, intense street harassment here in San Francisco, and although harassment doesn't convey the menace and threat. And sometimes assault I faced. Feminism is my life, climate is my planet.

Greg Dalton: You're listening to a conversation with Rebecca Solnit about the need for optimism in the climate imperative. This is Climate One. Coming up, why connecting with other people is so important.

Rebecca Solnit: We have to escape from consumerism, we have to escape from the kind of loneliness and isolation that Silicon Valley and a lot of other structures in our society have helped create.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Ariana Brocious: This is Climate One. I’m Ariana Brocious. Let’s get back to my conversation with activist and author Rebecca Solnit, talking about the connection between the climate crisis and the democracy crisis.

Rebecca Solnit: There's a lot more support for climate action than we're getting from politicians. That's partly about dark money and how expensive it is to run political campaigns. if we really had a one, you know, one person, one vote nation, if we had equal access to the ballot, if we didn't have the gerrymandering, the voter suppression, uh, you know, the st taking the vote away from people convicted of felonies even after they served their time, uh, and too many states, et cetera. If we had full participation, people, like, I remember there was that election when Jeff Sessions, the confederate chipmunk became, uh, um. Trump's secretary, attorney general. And then there was the special election, and you got like a right wing child molester versus a really nice moderate, moderate white guy. And it was really exciting that the white guy ran. But were black people fully enfranchised in Alabama, probably Alabama would have been sending really cool Democrats, probably, quite possibly black women to the senate all along. And then I think we can broaden the concept of democracy to say, how do people in the global North have the right to make decisions that affect people in the global South, you know, the South Pacific, sub Saharan Africa and remote places like the Arctic. The Circumpolar Peoples of the Arctic, um, how do the rich have the right to impact the poor more? Who, who will feel the impact more? You could even expand it to a democracy. How do human beings have a right to pursue our goals, if they're going to make other life, you know, other species extinct, our whole habitats extinct. So I think it's, in a way, just like I said, feminism is a democracy project. I think climate is a democracy project. And then another constituency is the people who were born yesterday. The people will be born in 50 years. The people will be born in 500 years. We don't have the right to steal the future.But the right, the we who are stealing the future is mostly the minority who are profiting from the status quo and trying to prevent the climate transition, because again, true democracy would let that transition roll forward.

Ariana Brocious: We're seeing, you know, the overturning of Roe v. Wade. There's been sort of an increase in censorship and, uh, silencing of other kinds of subjects that are, like, not allowed to be discussed in schools and taught to children and things like that. So it can feel like we're taking steps backwards. There's also been a real, um, political sort of backlash to the overturning of Roe v. Wade in states that are trying to pass their own protections. So how do you hold that? You know, kind of, um, maybe not despair, but, you know, disappointment with these major steps back, which can feel like steps back. And then also this, what's happened? What's the result has been?

Rebecca Solnit: The Supreme Court who overturned Roe versus Wade do not represent the people of this country. They were shooed in by minority presidents. Two out of three of Trump's appointments, I think, were corrupt. And, the Supreme Court has become a criminal organization. Certainly Clarence Thomas, um, has. And it does not represent what the public wants and believes is right. And we're seeing backlash, not only in states trying to pass their own, you know, and essentially killing Roe versus Wade, hands it back to the states. Some states are gleefully criminalizing essentially being a pregnant woman, uh, in this very handmaidens tale, 1984 kind of way. A lot of other states are looking at passing reproductive rights protection. But also, I often hear the narrative like, oh, women's rights took a step backward. But I want to enlarge the picture to say that in the last few years, Argentina, Mexico, and Ireland, three very Catholic countries, all granted women reproductive rights. And so if you get, you know, the U S is not the world. And I tend to think that ideas are the genie that's not going to get back into the bottle. Women in this country had 50 years of reproductive rights. We believe that we are entitled to them. Obviously there's a right wing backlash. I think it's a backlash against all the progress that was made, racial progress, gender progress, progress for queer and trans people, progress for indigenous rights and progress for environmental protection. You know, you can suppress the will of the people through brute force and the Republicans are clearly committed to being a minority party. They've given up on actually winning majority rule, which is why they're trying so hard to corrupt elections, suppress votes and voters, particularly black voters, It's not a good long term strategy for them. and I think that in the long, like, and I feel terrible for the women in Texas and other states who are being terrorized, tortured, forced to carry dead babies and fetuses that cannot possibly survive, et cetera, but, um, I don't think it'll last.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, this is actually a great segue. I'd like to ask you to read something and this is an excerpt from an essay you wrote in, following the 2016 presidential election called How to Survive a Disaster.

Rebecca Solnit: The ideal societies we hear of are mostly far away or long ago, or both. Situated in some primordial society before the fall, or a spiritual kingdom in a remote Himalayan fastness. The implication is that we here and now are far from capable of living such ideals. But what if paradise flashed up among us from time to time, at the worst of times? What if we glimpsed it in the jaws of hell? These flashes give us, as the long ago and far away do not, a glimpse of who else we ourselves may be and what else our society could become. The door to this era's potential paradises is in hell.

Ariana Brocious: I love that last line and this idea of finding paradise, of finding solace and comfort and community and togetherness in the worst of times. And, uh, you write in that essay and I think in some other places about responses to disasters like Hurricane Katrina. So, how did you come to this idea that these times that can seem like the most dire can actually be, um, really powerful and uplifting and community building?

Rebecca Solnit: San Francisco earthquakes taught me that. First, I lived through the 89 earthquake, as I'm sure a lot of you did, whose 34th anniversary was just a few days ago. And I was amazed to find that, like, all the things I'd been fretting about, simmering over, We're just completely erased like I was mad at somebody who was behaving badly. I never thought about him again and I just saw people. You know people all over the city came out and directed traffic because there was a complete blackout. People just figured out what needed to be done and did it. In North Beach, for example, the power was out for three days to restaurants rather than let their foods like, set out barbecues and started feeding the neighbors. People tried to rescue the victims of the freeway collapses. There was a group called Seeds of Peace that had fed the great anti nuclear peace marches, was set up community kitchens and fed the first responders. who were working at the freeways. The fire department putting out the fires in the marina was only able to do that because huge numbers of volunteers showed up to help them run those hoses from the ocean to, to get some water, et cetera. And then I was commissioned to write an essay in advance of the centennial of the 1906 earthquake. And I found again, all these remarkable stories of, not what we'd always been told about disaster, movies and a lot of conventional coverage of disaster, including the journalism of the 06 earthquake and the incredibly criminally Racist journalism around Hurricane Katrina is an assumption that human nature is basically corrupt in when Authority falls away in the chaos of a disaster. We revert to our primordial nature particularly poor people. And that nature for men is ravening wolves plundering looting raping marauding etc for women, um, especially if it's movies with Charlton Heston or Tom Cruise in, in them, um, women become helpless idiots who need to be rescued by strong men. The stories they tell really reinforce the narrative that we need strong authority but what you actually see in disaster that authority often ceases to exist or becomes obsessed with protecting its own power and private property, which is the least important thing compared to human life in a disaster. Authority often fails hideously. Civil society, the first responders in any disaster are your neighbors. And what happens is that by the time the news cameras get there, the professionals have often also gotten there. You'll get these exciting search and rescue teams who are wonderful. But if you've been pulled out of the rubble that first day. it's probably the neighbors. People are resilient, um, generous, empathic, creative, courageous, and that's sort of like, you know, rising to the occasion. That's kind of very wholesome. But what I found fascinating is that over and over in stories from 911, from hurricane Katrina, when they weren't stories about the racist violence of the police and the white supremacists and, um, the blitz, uh, the bombing of London, Iin the 1906 earthquake, there's a kind of luminous and a joyfulness in people's accounts that told me, we're always told capitalism, consumerism, and in a sense, therapy culture tells us we want, we want material comfort and safety and we want the pleasures of private life, love, sex, nice, nice things. But I think what we want most deeply is meaning, purpose, belonging, agency. And we lack those. And what's astonishing is that people are never, that's not the story we hear about who we are and what we need, but people are so deeply fed when they find it in these moments, even when there's been a lot of death, even when their house has been, has burned down, that they're often joyful and bold in a way you don't see otherwise. I wrote a book this relates to called A Paradise built in Hel,l the extraordinary communities that arise in disasters. the book came out in 2009. I did the research, you know 2007 and 8 Partly because after Hurricane Katrina, I thought we really needed the equipment to understand Who we really are in disaster, who misbehaves, who behaves well, et cetera. Because that's like most of the people who died in that hurricane died in New Orleans and they died essentially because of racism and, um, the callousness of and stupidity of the authorities in charge from the Bush administration to the governor, to the mayor. But, um, And I knew that climate change meant that we would have more disasters and more intense disasters, and we needed to understand who we were in the face of disaster. And I wish I was wrong about that. What I didn't understand is that in some ways disasters would become normalized. And the wildfires California had, um, in 2017, 18, 19, 20 were big news stories. Canada just had the biggest news fires in recorded history and like they barely got reported on. The New York Times and a lot of the mainstream media made me crazy because they kept reporting on the smoke and it's like, Hey, have you ever heard that where there's smoke, there's fire? There was almost no coverage of where the smoke was coming from. And of course Canada, you know. Margaret Atwood once said Canada is behind the world's longest one way mirror, and so what I worry about is that we normalize it that like, you know, ten thousand homes burning here five hundred people drowning there crop destruction Famine here that there's so much of it. It will become normalized which is something I hadn't really anticipated.

Ariana Brocious: But this idea that people really come together and find like a truer sense of being in these situations, I think is one that is very hope filling when you think about what future... Most likely, uh, you know, even if we do accomplish what we're hoping in terms of keeping climate impacts lesser, we're still going to have them, we're going to continue to have them, and we're going to have to find that resilience. What have you changed your mind about, and why?

Rebecca Solnit: In order to do what the climate requires of us. There's a lot of very practical, wonky stuff. You know, and very physical stuff. We need to change, we need to electrify everything. We need to change how this, what the world runs on. But I also think that we need to Change our imaginations, our values, our relationships. What's encouraging about how people respond to disaster is you see this deeper sense of who we are and what we really want, who we could be. And I feel like we have to be... We have to escape from consumerism, we have to escape from the kind of loneliness and isolation that Silicon Valley and a lot of other structures in our society have helped create. We have to feel that we can have an age of abundance, but abundance will be in confidence in the future and the society we live in, confidence in our institutions and each other, a sense of belonging, um, a quality of life that will lie in our relationships to other human beings, other species, the natural world.

And so I feel like that what disaster shows is that this is who we can be. It kind of shows a way forward, but we need to change the stories we tell about what a good life, a good society, wellbeing look like as well. It happens all the time. I've changed my mind a lot. because I've learned a lot of things. Um, I was not that hopeful in the nineties, I had a lot of things that resurgence of indigenous voice agency, visibility, et cetera, changed my thinking, um, that seeing, seeing that starting, really seeing it starting in 92, seeing the collapse of the Berlin wall and the fall of the Soviet bloc states, um, made me, uh, a number of other things made me believe that culture, culture can change politics, politics shapes, the physical, um, you know, and administrative world we, um, live inculture matters in a way I wasn't sure it did, even though I'd committed myself to it as a writer. and a lot of it is just learning and writing recollections of my non existence.

I finally understood everything I'd written about feminism was about, wasn't about violence, but it was also about voice. So a lot of it is just understanding better. And one of the joys of being a writer that I always hoped is shared by the reader is understanding something better, seeing something more deeply, finding out something. In my book, Orwell's Roses, I found out nobody who wrote about Orwell was very interested in the fact that he was an absolute passionate gardener who took deep joy in the natural world and maybe it didn't matter to people writing those books in the 70s 80s 90s. But I think for our time it matters and so my mind changes all the time and I think we just call it learning, and hopefully having a little bit of flexibility, you know, I've learned so much. I heard W. Kamau Bell say that he would have talked about race differently had he known then, ten years ago, what he knows now, I think we've all had an incredible crash course in thinking about race, thinking about trans identities, about gender, and getting past the binary, you know, we've had, we've all learned a lot about climate. So if we're learning, we're changing, and we're changing our minds.

Greg Dalton: On this Climate One... We’ve been talking about why it’s not too late for climate action with Rebecca Solnit.

Climate One’s empowering conversations connect all aspects of the climate emergency. To hear more, subscribe wherever you get your pods.

Ariana Brocious: Talking about climate can be hard-- AND it’s critical to address the transitions we need to make in all parts of society. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. You can do it right now on your device. You can also help by sending a link to this episode to a friend. On our new website you can create and share playlists focused on topics including food, energy, EVs, activism. By sharing you can help people have their own deeper climate conversations.

Greg Dalton: Ariana Brocious is co-host, editor and producer. Brad Marshland is our senior producer; Our managing director is Jenny Park.. Austin Colón is producer and editor. Megan Biscieglia is our production manager. Wency Shaida is our development manager, Ben Testani is our communications manager. Our theme music was composed by George Young (and arranged by Matt Willcox). Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.