This Year in Climate: 2023

Guests

Rev. Lennox Yearwood Jr.

Kathy Baughman-McLeod

Ali Zaidi

Jane Fonda

Nalleli Cobo

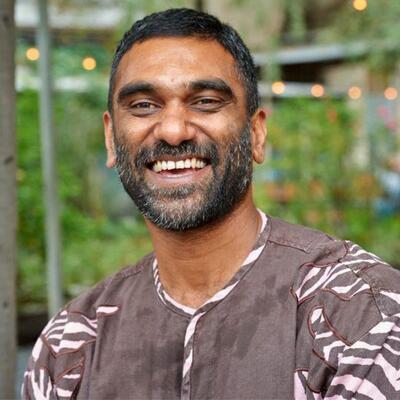

Ralph Chami

Bernie Krause

Paolo Bacigalupi

John Curtis

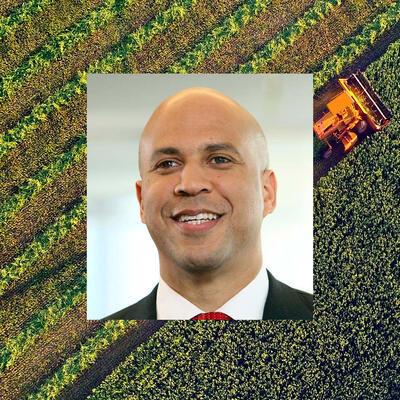

Cory Booker

Rebecca Solnit

Summary

It’s been a year of weather extremes — again. But there’s also been cause for renewed hope about our climate future.

This year, the 28th annual United Nations Conference of Parties, or COP, was held in Dubai. Negotiations went into the wee hours of the night and ended with a surprising result: The final agreement not only uses the words “fossil fuels” for the first time, but the nations of the world have now agreed to a global pact that explicitly calls for “transitioning away from fossil fuels” beginning this decade. They also agreed to quit adding carbon dioxide to the atmosphere entirely by midcentury.

The agreement is unenforceable, and polluters could still exploit loopholes to ignore the promises. But words matter. This signals to investors and policy makers that the end of fossil fuels is finally beginning.

Meanwhile, 2023 was the hottest year on record. The world saw raging wildfires, catastrophic floods, and many other extreme weather events. Between 2018 and 2021 deaths from heat alone rose 56%. Kathy Baughman-McLeod, Director of the Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center says,“The scary part is a lot of times these [heat] deaths and illnesses are masked. You know, it's called the Silent Killer for a reason. We don't hear it. We can't see it, and we don't have a lot of data that tells us.”

This year also saw the policies embedded in the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act begin to be implemented. White House Climate Advisor Ali Zaidi says that people's lives are at the heart of the Biden Administration’s efforts to reduce emissions and prevent dangerous warming. “When we go about tackling the climate crisis, we're not just measuring our progress in terms of clean energy, gigawatts built or greenhouse gas, million metric tons reduced. We measure it in the people who felt left out, left behind,” says Zaidi.

This past year was not only a time of extreme weather, but of increasing demonstrations protesting that not enough isi being done to address the climate crisis. Jane Fonda, a famous actress and activist, says, “I have found that every single time I start to get depressed, if I take action it disappears. Greta Thunberg said, don't go looking for hope, look for action and hope will come. And she's right.”

Nailli Cobo, a young climate activist based in Los Angeles, personally experienced the consequences of fossil fuel extraction. She was afflicted with horrendous nose bleeds stemming from the oil well just across the street from her apartment. “It got to the point where the nosebleeds got so intense I couldn't sleep in my own bed anymore. I would have to sleep in a chair to prevent choking on my own blood. I developed asthma and that's something I'm always gonna have to live with.” Cobo became an activist at age nine, helping to secure passage of an ordinance that banned new oil and gas development and will phase out existing wells in LA County. This year, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed a bill banning new wells within 3,200 feet of schools, homes and buildings. But oil companies have managed to put an issue on next year’s ballot to overturn those community protections.

It can be easy to feel overwhelmed by the climate crisis. And sometimes that can cause people – especially in wealthy countries in the global north – to ignore the problem or even just stop trying to address it altogether. But author Rebecca Solnit says, “We who are relatively comfortable, safe, affluent, and therefore powerful, I think have no moral right to give up.”

Reverend Lennox Yearwood Jr.,CEO of the Hip Hop Caucus, says, “You have to have a strong faith. To believe that it's just not you. That it's something bigger than you. And that's something that will carry on this fight. And that one day, and at this time, my goodness, with all that's going on and so much pain and so much trauma and so much hurt, you just got to believe that one day, the more that we keep fighting for justice, one day as humans, we will come together and we will make this planet a good place.”

A previous version of this episode incorrectly stated that the COP28 agreement includes a transition from fossil fuels this decade. While the deal calls for the transition to happen in “a just, orderly and equitable manner,” it does not include a timeframe. We regret the error.

Episode Highlights

4:21 - Kathy Baughman-McLeod on the dangers of heat

5:12 - Ali Zaidi on big climate initiatives in the Biden Administration

11:15 - Jane Fona on the importance of taking action

14:41 - Nalleli Cobo shares her personal story living near an oil well.

18:29 - Ralph Chami on blue whales

21:25 - Bernie Krause on how climate changes the soundscape

24:47 - Paolo Bacigalupi on writing climate fiction

28:25 - John Curtis on what we have in common

31:32 - Cory Booker on bringing people together

36:31 - Rebecca Solnit on taking the long view of progress

40:50 - Rev. Yearwood Jr. on the climate activism in the wake of Hurricane Katrina

Resources From This Episode (5)

Full Transcript

Note: Transcripts are generated using a combination of automated software and human transcribers and may contain errors. Please check the actual audio before quoting it.

Greg Dalton: I’m Greg Dalton.

Ariana Brocious: I’m Ariana Brocious.

Greg Dalton: And this is Climate One.

[music change]

Rev. Yearwood Jr.: It's time to stop polluting our communities, polluting our world. We don't have much time and we must end the climate crisis now.

Ariana Brocious: That’s Reverend Lennox Yearwood, the inspirational leader of the Hip Hop Caucus, and one of our most compelling interviews of 2023. We’ll hear more from him later in the show.

Greg Dalton: A lot has happened in 2023 and we’re spending today reflecting on what made us feel a pang of fear and a jolt of excitement. We’ll talk about the year that was, and look ahead to 2024.

Ariana Brocious: In this hour we’ll hear from a bunch of amazing, insightful people with ideas for real climate progress.

Greg Dalton: First we're going to start with the news.

Ariana Brocious: The 28th annual UN climate conference has just wrapped up in Dubai. And you were there.

Greg Dalton: I was. And I’m surprised by the outcome reached in overtime. The Conference in an OPEC country resulted in nearly 200 nations agreeing to “transition away” this decade from fossil fuels – oil, gas and coal.

Ariana Brocious: This is a really noteworthy achievement. It’s a big surprising win for conference president Sultan Al Jaber. For decades, petrostates such as Saudi Arabia had blocked even mentioning the words “fossil fuels” in these climate agreements - which is pretty shocking in its own right.

Greg Dalton: Right. And Al Jaber faced fierce criticism for being an oil executive leading a conference aimed at reducing fossil fuels. Now he proved his doubters wrong.

Sultan Al Jaber: We should be proud of our historic achievement. We have given it a robust action plan to keep 1.5 within reach. It is a plan that is led by the science. It is the U.A.E. Consensus.

Ariana Brocious: This is big news for climate.

Greg Dalton: The agreement is unenforceable, and there are still lots of loopholes and opportunities for polluters to ignore the promises. But words matter. This is a signal to investors and policy makers that the end of fossil fuels is finally beginning around the world.

Ariana Brocious: There’s a lot in the agreement so we’re just going to hit a couple of other highlights: It also aims to halt and reverse deforestation. The deal also calls for tripling renewable energy production by 2030. And that in itself is a big audacious goal that will be challenging to meet.

Greg Dalton: Right, though we can’t possibly stop using fossil fuels until there’s enough clean power to replace it.

Ariana Brocious: The agreement overcame objections from fossil fuel producing nations including Saudi Arabia and Iraq – and emerging economies such as Nigeria and India that are running on fossil fuel or dirty energy.

Greg Dalton: This whole process is based on peer pressure. Individual countries still get to decide their own timelines for transitioning away from fossil fuels.

Ariana Brocious: And those timelines are running out. Turning to other climate news… IT WAS SUCH A HOT YEAR, AGAIN. This October was one of the hottest ever, and I bet listeners could feel it. Here in Arizona, I certainly could. I kept waiting for things to cool down.

Greg Dalton: Yeah me too. And that's a dangerous trend. Deaths from severe heat increased 56% in the U.S. between 2018 and 2021. We talked with Kathy Baughman-McLeod from the Adrienne Arsht Rockefeller Resilience Center, who’s working with communities to deal with extreme heat.

Kathy Baughman-McLeod: The scary part is a lot of times these deaths and illnesses are masked. You know, it's called the Silent Killer for a reason. We don't hear it. We can't see it and we don't have a lot of data that tells us.

Greg Dalton: As climate awareness has moved into the mainstream, we find ourselves talking more about all the ways burning fossil fuels impacts our lives. And the truth is that energy (and water) intersect with everything around us. If you are wealthy you may not notice the strains on the food, energy and water systems. If you are poor, you probably feel those strains more directly.

Kathy Baughman-McLeod: The story of extreme heat is a story of race and a story of discrimination. Exposure to extreme heat increases asthma. It means that you have to run the air conditioner more, and if you don't have air conditioning, that heat exacerbates underlying conditions that people have and people in food deserts with little access to healthy food and healthcare end up having their conditions like diabetes or heart disease exacerbated by heat.

Greg Dalton: This is an environmental justice problem – one that the Biden administration has been working to address. Earlier this year I spoke with White House Climate Advisor Ali Zaidi about the administration's work on gathering momentum and excitement around big ticket climate initiatives:

Ali Zaidi: We have a relentless focus on getting greenhouse gas emissions down, but we have such a bigger opportunity right now, and that opportunity is to restore that American dream. And so when we go about tackling the climate crisis, we're not just measuring our progress in terms of clean energy, gigawatts built or greenhouse gas, million metric tons reduced. We measure it in the people who felt left out, left behind. How many of them can we pull into the fight as we move forward.

Greg Dalton: If 2022 was the year of big legislation – with passage of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Act and Inflation Reduction Act, 2023 was a year of policy implementation. Of course that will take a long time to roll out and see the benefits. But it's starting to get underway.

Ali Zaidi: The amount of investment we've seen triggered by this policy means that by 2030 the US will be capable of producing 13 million electric vehicles worth of batteries. That's a really big deal. We sold 16 million vehicles total last year. So think about the pace of the transformation. We have increased, by the end of his first term, we will have increased our ability to manufacture solar panels by eight x. We're conserving land. We are dealing in the agriculture sector. 60,000 farms, 25 million acres of farmland in the US signed up for climate smart agriculture. So, you know, if you're a climate voter in 2020, you did what everyone bet against was possible for decades, what had seemed completely out of reach, that every single sector of the economy would be now lined up with irresistible economics driving towards decarbonization, and that we'd be doing it in a way that's centered around workers and communities and justice. I don’t know what greater evidence there is of democratic power in propelling a system that had run on emissions for decades toward decarbonization.

Greg Dalton: The scale of the things he’s talking about really are broad and deep. The concern of course is that a Republican president might try to claw back some or all of those gains.

Ariana Brocious: Right and that would really slow the momentum we’ve started to see. Let’s each share something positive and negative about the year in climate news, and then we can talk about other things we’re keeping an eye on.

Greg Dalton: Let’s do it.

Ariana Brocious: I’ll start. My high was the successful case brought by Montana youth against their state, using language in the state constitution about the right to a safe and healthy environment. That was a big legal victory for climate and we’ll see what it means. We did a whole episode on the rise in climate court cases and I’m watching that space to see what develops. What about you Greg? What was your good news story from 2023?

Greg Dalton: Oh it’s so hard to pick. There is so much good news happening. Eight countries are scaling renewables at a pace that shows the Paris goals are achievable and possible. I had a mangrove awakening: they’re really powerful at sequestering carbon. My biggest one is when I heard Al Gore say that once greenhouse gas emissions reach zero, global temperatures would stop rising in just a few years. That’s really powerful and means that global leaders could actually see and experience the benefits of decarbonizing.

And your low, Ariana?

Ariana Brocious: My low would have to be the continued slowdown in actually taking the action necessary to address climate change. We’ve know for a really long time what needs to happen. This year we saw the UK prime minister roll back climate goals, which was really disappointing since they’re one of the global leaders in taking action. And here at home, we’re waiting to see the outcome of next year’s presidential election and what THAT could mean for the climate agenda President Biden has put in motion. Greg, what’s keeping you up at night?

Greg Dalton: So many things. I’m a terrible sleeper. And most importantly the human cost of involuntary migration of people thrust from their homes due to drought and food insecurity. At this year’s climate summit in Dubai and last year in Egypt, we sought out people from the global south who have these stories to tell. I looked them in the eye and really listened. And they’re suffering. And that suffering is caused by us burning fossil fuels.

Ariana Brocious: And that’s going to continue as long as we don’t take the action that’s needed. Okay now let’s quickly talk about what we’re watching in 2024. For me that’s a couple things: climate litigation at home and abroad, as I already mentioned, and also the continued developments around the electric grid. This is something we covered in another episode and it’s wonky and complex, but so essential! Because we have to be able to move all the renewable power we’re building out to the places that need it. Greg, what are you keeping an eye on?

Greg Dalton: Ballot boxes. The Economist reports that 2024 is the biggest election year in history. Countries with more than half the world’s population - four billion people - will send their citizens to the polls. Elections in the US, UK and India will have a major impact on how fast we move away from fossil fuels.

Ariana Brocious: And you know, as we cover all this climate news it can be easy to maybe get bogged down or depressed about where we’re at. But a lot of people – including many we talked with on the show this year – say taking action makes them feel better. One of those was the incomparable Jane Fonda.

Jane Fonda: I have found that every single time I start to get depressed, if I take action it disappears. Greta Thunberg said, don't go looking for hope, look for action and hope will come. And she's right.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, there's research that backs that up, that doing, it helps, and the community you find in doing is part of that, the relationships, it's the action in concert with other people.

Jane Fonda: Exactly.

Greg Dalton: You were arrested in Washington, D. C., it was your first time since the 1970s. You were arrested with a bunch of celebrities,

Jane Fonda: And a bunch of non celebrities. I mean, this wasn't just all about, what I loved about it is celebrities introduced active, frontline activists, you know, who normally, whose voices wouldn't be heard and it was all recorded, and we have it in perpetuity, and hundreds of, I mean, lots and lots and lots and lots of people watch this stuff. And people travel from all over the country, mostly women, mostly older women.

Greg Dalton: Many of whom watched your videos and that's why they were there.

Jane Fonda: Well, they like Grace and Frankie too. You know, I mean, I've been out there in the trenches as an activist when people really hated me. And then I've been out there in the trenches when I was Grace and Frankie and people loved me. And so I've been at both, and it really helps to have a good, successful TV series behind you if you're going out there.

Greg Dalton: You had your mugshot taken. You were handed a bologna and cheese sandwich. You were locked in your cell. Take us to that moment. What were your thoughts and feelings? When you click, you're in a jail cell in Washington, D. C. for protesting on climate.

Jane Fonda: This, this may sound weird, but when you are putting your body on the line for something that you would give your life for, the deepest thing you can possibly believe in, there is, while they're putting the handcuffs on, those white plastic things, they hurt like hell. But you feel so liberated.I felt so free. It was weird, huh? But, you know, I'll have to be honest. I'm white, I'm famous, I'm privileged. So I knew they weren't going to hurt me. I knew that I was safe. So, it was really my job to kind of like record what was going on.

Greg Dalton: So you did that for a period of time. Many people were arrested. Famous people, regular people, lots of brave people. What do you think that Fire Drill Fridays accomplished?

Jane Fonda: Okay. We were not, as has been reported in the press, our goal was not to affect government. Our goal was, look, we know from the Yale Communications Project, Climate Communications Project, that... There are a majority of Americans, like 70%, are very concerned about the climate. But they haven't taken action. And they say because they haven't been asked. The great unasked. This is our job now. Is to reach the great unasked.

Greg Dalton: We've also got a lot of active climate folks with far less privilege, people who are making a big difference in their communities.

Ariana Brocious: One young person giving me hope is Nalleli Cobo. She lives in South Los Angeles, and her apartment is right across the street from an oil well. She became an activist after she started having severe health problems starting around age 9.

Nalleli Cobo: It got to the point where the nose bleeds. Got so intense I couldn't sleep in my own bed anymore. I would have to sleep in a chair to prevent choking on my own blood. I developed asthma and that's something I'm always gonna have to live with now. I had heart palpitations and I had to use a heart monitor for several weeks. I got body spasms that were so intense I couldn't walk. My mom would have to carry me from one place to the other. Unfortunately the list goes on and on, and it wasn't just me. My mom developed asthma at 40, which is really rare, and my grandma developed it at 70, which is unheard of.

Ariana Brocious: Nalleli ended up with reproductive cancer as a result of her exposure. She was incredibly resilient and sacrificed her youth to fight the industry and its toxic exposure.

Nalleli Cobo: Because I was so young, I didn't realize what I was up against. I just thought I was fighting grownups. But I did not understand that I was fighting big oil, a multi-billion dollar corporation, and I think it helped a lot not to know that at the age of nine.

Ariana Brocious: She had a few BIG successes–shutting down their neighborhood well and helping to secure the passage of an ordinance that banned new oil and gas development and will phase out existing wells in LA County. This year, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed a bill banning new wells within 3,200 feet of schools, homes and buildings. But oil companies have managed to put an issue on next year’s ballot to overturn those community protections. So Nalleli is still fighting.

Nalleli Cobo: Lives are on the line. There are over 4 million Californians living a mile or less to an active or idle oil and gas. Think of your mom, think of your grandma, your niece, your nephew. Because these are human lives, oftentimes we get distracted by the big number or the dots on the map, and we forget that every dot represents a human. And for me, I felt like at the age of nine, someone could look at me in the eyes and say, you don't deserve to breathe clean air. But what they didn't know was that I was a nine year old who was, still is, obsessed with Justin Bieber, that I love dance, that I love music, that I love eating, that I love hanging out with family that makes me who I am.

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to Climate One’s year in review episode. If you want to go back and listen to one of the previous episodes we’ve mentioned today, check out the show notes for links. Or simply subscribe to our podcast wherever you get your listen.

Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. You can do it right now on your device. You can also help by sending a link to this episode to a friend.

Up next: how knowing the carbon-holding value of a blue whale could make us appreciate them more:

Ralph Chami: So, if they could speak our language or if we could understand their language they’ll be saying, hey, dude, why don’t you pay me? I’m helping you survive.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton.

Ariana Brocious: I’m Ariana Brocious, and it’s our annual year-in-review show.

Greg Dalton: We talked about a LOT of different issues and ideas on the show this year: including the role of agriculture, how to decarbonize the trucking industry, and the role of nuclear and hydrogen in a clean energy future.

Ariana Brocious: We talked about the crazy energy demands of bitcoin, and the history of the American Buffalo. We had great conversations with economists, scientists, activists and musicians, and even people who helped us understand what some animals might think or say about climate changes. One of those was Ralph Chami, an economist with the International Monetary Fund who fell in love with blue whales.

Ralph Chami: I remember that moment it’s like today. I looked at her and I thought what are you how is it that I didn't know you existed? And by the way, you have to understand the blue whale is the largest creature that has ever lived. You can fit an African elephant inside her mouth and would disappear completely. I mean, she could've swallowed us and no one will ever know but she didn't. She fed gracefully around us.

Ariana Brocious: He came up with an economic argument for why we should protect them. When they’re alive they eat plankton, which absorb CO2, and when the whales poop, it sinks to the sea floor, effectively removing that carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. And when a whale dies, it also provides a carbon sequestration service:

Ralph Chami: And what I was interested in because economists and finance people think, on average, how much does a great whale capture carbon on average. I had to calculate it myself. And that's the number now that you see all over the world. People talk about 33 tons. That's basically my number.

Ariana Brocious: And put that number in a context for us. What does that represent when people are thinking about carbon?

Ralph Chami: That represents 1500 trees on the body of a whale. And that whale because they are negatively buoyant because they’re so heavy. When they die, they sink. And anything that sinks below a thousand meters is sequestered forever unless you disturb it.

Ariana Brocious: Ralph Chami wants us to consider the value whales are providing to us and compensate them for it, by protecting them and their habitat.

Ralph Chami: Think of it this way. I work for the IMF and I provide the service and they pay me a salary. The IMF does not pay me a salary because Ralph is a nice guy, nor that Ralph is a husband or a father or a good citizen. They just because I provide a certain service that the IMF is interested in. Okay, well, here's a whale and it’s providing a carbon sequestration service on behalf of humanity. If she could speak our language what would be the wage that she would demand? That’s it. Because after that people said, oh, you’re pricing a whale. I said, no man, what I’m trying to tell you is the whale, unfortunately, doesn’t speak English, doesn't speak dollars and cents. And so, we've taken them for granted. Well, they are going around helping us fighting climate change. The whale, unfortunately, doesn’t speak dollars and cents. And so, we've taken them for granted. Well, they are going around helping us fighting climate change. So, if they could speak our language or if we could understand their language they’ll be saying, hey, dude, why don’t you pay me? I’m helping you survive.

Ariana Brocious: When you think about it that way, there are so many species who might have a thing or two to say about how humans have ruined the environment.

Greg Dalton That reminds me of a conversation I had with Bernie Krause. He’s a soundscape ecologist and he uses audio recordings to document ecological collapse and biodiversity loss. He can literally hear extinction happening.

Bernie Krause: When an environment is healthy, the sounds are defined in these very carefully illustrated niches. When it’s under stress that all breaks apart and especially when the human noise is an issue that's causing the stress in that habitat. And all of the critters search for their niches so that their voices can be heard so that they can survive. When a habitat is sick, it shows in its voice. And I think we got to pay some attention to that because we can hear the changes that are taking place now.

Greg Dalton: Right. And so much of the mainstream news media is filled with images of melting glaciers, etc. burning forest. You once wrote “A great silence is spreading over the natural world, even as the sound of man is becoming deafening.’ How did you come to that conclusion?

Bernie Krause: Well, because in my recordings over the years I’ve been recording now since 1968. My recordings over the years I'm seeing the changes over time when I go back and visit revisit these places that I've captured years before. And the density and diversity of wildlife of focal wildlife, birds, insects, frogs and some mammals has changed radically.

Greg Dalton: It’s amazing and heart-breaking. He can hear the changes over time when he returns to places where he made recordings years ago. One place in particular was Lincoln Meadow in the Sierra Nevadas in California.

Bernie Krause: They had told the residents around that area that they were gonna do a new model of logging called selective logging, taking out a tree here and there. It was relatively new at that time. And that there be no environmental impact as a result. And I said fine I said can I go up and record before you do that. And I did. I went up in June, right on the solstice of 1988, recorded that habitat in the Sierras at about 06700 feet. And that summer the logging company did their selective logging bit and I came back exactly a year later under the same conditions and recorded again. And what I found was that not only were there not a lot of birds there, but they weren’t singing very much. And even though with a photograph the place looked unchanged. There didn’t seem to be a stick or a tree out of place. But to the ear the difference was astounding. It was so quiet and so scary.

Ariana Brocious: I find it really exciting all the ways people are using creative tools to talk about climate change. Another person who comes to mind is the author Paolo Bacigalupi. He writes speculative fiction, and his stories are filled with dark climate futures. Some of them are really scary. And Paolo told me that’s intentional.

Paolo Bacigalupi: I hope to wreck their home. Like, I mean, I hope to make them feel like the walls of their home are closing in on them. That nothing that they live in is stable or secure. I hope that like they are horrified and think, oh, just because today looks good doesn't mean tomorrow is safe. To leave them so profoundly disturbed that their home no longer feels like a safe place and they have to start engaging with the external world that like is sending us signals all the time, but we continue to find our ways to ignore.that either with our, you know, our Netflix or our Instagram or whatever the thing is. It's like keeping us involved in the slap fight of the moment or whatever it is, instead of like looking at the big pattern of like, where is our future headed?

Ariana Brocious: Denise Baden, who's the editor of this No More Fairy Tales anthology, and she says that, , Fear is an effective driver of plot and it can be an entertaining tool., stories that instill fear, but that overall that's counterproductive and actually generating the change we wanna see like in the climate

Paolo Bacigalupi: I am sympathetic to the idea. , I think that if you want to create, , change in a democratic society, people have to believe that there is actually a threat., in order for them to believe that climate change matters, they have to extrapolate forward into what climate change is, and they have to have that grounded well enough in their world, in their physical spaces that they. It's no longer an abstraction that they think, oh, maybe in 30 years they have to think maybe my property values are gonna die in five, and that's a problem. And so we need to deal with it. If you don't make it visceral and bring it into their world, , I'm not sure that you get the kind of democratic sort of upwelling of concern that moves politicians or that gets people onto planning boards or planning commissions and stuff. I think in very young people, I think that there's a, a stronger sense of emergency, but, , I. I think that there's a huge value in generating unease in people who are otherwise feeling like I can probably skate by. Um, you really want to kind of illustrate like, well, what happens if our insurance industry completely collapses because we didn't do the, um, sort of risk analysis correct on how hurricanes and other climate emergencies are going to damage. You know, our, our infrastructure, um, you want them to feel like, oh, just because I live in a safe space doesn't mean that that actually is a safe space. You want it to impinge and impinge and impinge.

And so I get the critique of, you know, dystopian stories or apocalyptic stories. I mean specifically apocalyptic more than, you know, dystopian. But like that these things might be. You know, bad or motivate people in bad ways or create the wrong framework for people to understand how to engage with big challenges.

Um, it's totally possible. , I think though that there is this element that. A well-written story of warning can create a sense of unease and a sense of awareness that otherwise doesn't exist for people.

That means something finally to them. And so that means that they're suddenly alert and engaged, in a way that they weren't before.

Ariana Brocious: Of course people understand and experience the climate crisis in so many different ways. Making progress on climate solutions starts with communicating and understanding each other. And that can come down to the words we use.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, this year I had two conversations with Representative John Curtis, a Utah Republican who chairs the Conservative Climate Caucus. And we talked about how the words we use can contribute to miscommunications that distract us from what we have in common.

John Curtis: I think we do this on a number of issues and not just climate. I think you could point to immigration and other issues where we just quickly bring up these, these, these words or these terms that are divisive that spread us apart. And at the end of the day, there's actually very little that separates us on climate as Republicans and Democrats. And there's far more that we agree on. And Republicans do want to leave this earth better than we found it. We have ideas on reducing emissions and I think a lot of Republicans make the assumption that to be good on climate, they have to embrace the green new deal. No, they have to bring their ideas to the table. And I also talk a lot about the fact that the myth is that we need to give up energy independence. The myth is that we need to give up low prices. The myth is that we have to give up affordability to reduce emissions. And I think that's turned a lot of Republicans off – that myth. And so we talk about the fact that like, let me show you how we do this without sacrificing energy independence. Let me show you how we do this without sacrificing affordability, reliability.

Greg Dalton: I saw that you met with some Olympians about reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Utah's in the running to host the 2030 Winter Olympics. Many of those events would happen at ski resorts in your district.

What do you see as your role in that effort from a climate standpoint?

John Curtis: First of all, let me say, use this opportunity to point out, uh, in a, in a very red state, Utah, very, very conservative state. Uh, we do a lot of oil and gas and coal that, um, one of the, one of the ways that we can get people turned on to this conversation is to show them how it impacts them directly. So in Utah, when you talk about the ski industry, um, people, all of a sudden sit up and listen and say, okay, I'm listening, right? And it's not and so it's it's easier for me to point out the shortness of the ski season the the that is starting later and ending sooner than it is something you know 10 000 miles away or 2 000 miles away And so I think this is a really good opportunity to say look local situations sometimes are what What it's going to take to get people engaged. And for me, two things. Well, really, three things have been very important pointing out what it's doing to the ski industry in Utah, pointing out the wildfires that we're having and the drought. And these are three easy place for very conservative Utahns to jump into this conversation. And to care. And let me tell you, they care deeply about the Great Salt Lake and the shortage of water. Utahns, regardless of the political affiliation. They care deeply about forest fires. They care deeply about the ski season. And these are not political issues. And so for me, having these things in my state has been a good opportunity to get people engaged who might not otherwise engage in this conversation.

Greg Dalton: Those myths he’s talking about are rooted in the information bubbles we live in. And we can actually have a lot of the same things. Renewable energy is cheaper and cleaner and can be all-American.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah. And this idea of needing to connect on shared values and terms is something we also talked about with Senator Cory Booker, a Democrat from New Jersey.

Cory Booker: I want people to expand their understanding because the most toxic threat to our nation right now I believe this. we have real problems in America and we have real problems globally. But I think the most toxic threat is the hate that is growing on Americans for each other. And this is creating an environment where we can't even talk to each other or far more common values. I was campaigning pretty hard in the last midterm election traveling all around the country. And I sat down on a plane and I often have people saying nice things to me. Often, unfortunately, people usual send me Mother's Day cards because I often get called “you mother" or something else. So, I get all kind of reactions across America as I crisscrossed the nation. But people are being really nice to be on this plane ride and I sit down next to a mom and a daughter 80 and 60 and they don't know who I am. And here I am large African-American male and for my ego some people might think this is wrong, but for my ego I love hearing what they said. They go, sir, who are you? Are you a professional athlete? And I'm like, well, I could be if I wanted to. But I said no ma'am, I'm a United States senator. And immediately all of us in America, if you need a politician congressperson you want to know what tribe they’re in. Are they in your tribe, their tribe or my tribe? The other-izing, the impersonality of that. Where do you stand with me or against me? And too much we have a binary world in America. And I said ma'am, I'm a Democrat. And she looks angry at me and says, I should've brought my Trump hat. Now there is a moment, all of life our power is not in what happens to us. Our power is never in the stimulus, it's always in the response. And we have a choice to respond with love, empathy, compassion, or to respond with negativity, hate lower frequencies of our being. And I look at the woman and I'm not dancing to this tune. And I look at her and I go, oh my gosh, Donald Trump, he signed two of my biggest pieces of legislation into law. And she seems surprised by that. And I go through some of the common values of that legislation. One on criminal justice reform. One on getting investment into low income rural and urban areas in America. And the record was scratched. It’s a long flight, but at the end of the flight we are talking about our personal lives. I learned about their family, they learned about mine. We’re affirming our commonality and talking about some of the problems in America being we don't talk to each other.

Ariana Brocious: Cory Booker is a compelling, compassionate speaker, and you can tell that he’s also a deep listener.

As consciousness grows more things become possible. Civil rights legislation failed for years until consciousness grew and we all get things done. But for now, we have got to be better at looking for win wins and not falling into a partisan divide. We have to commit ourselves to creating more dialogue, more ability to affirm each other's humanity and still believe that we have common cause in this country. Because when America acts with a sense of increased compassion and empathy and common cause we dazzle humanity in what we achieve. From immigration laws that let the entire plan is diversity come here and breakthroughs in science defying gravity going to the moon to even affirmations of human rights and human dignity that have put us as a standard bearer for our planet. We can do these things when we stop hating each other. And even if we disagree, find ways to affirm this commonality. I call it love, people who call it just affirming your fellow citizenship.

Ariana Brocious: You're listening to Climate One’s end of year episode. Coming up, in the midst of a climate catastrophe, humans show up for each other – sometimes in surprising ways.

Rebecca Solnit: What's encouraging about how people respond to disasters, you see this deeper sense of who we are and what we really want, who we could be.

Ariana Brocious: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. We’ve been talking about some of the most compelling conversations we had on the show over the last 12 months. I feel grateful there are almost too many to mention.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, I agree. You can hear all of them on our website, or in our podcast feed. One of my favorites this year was with activist and author Rebecca Solnit, a person who’s written many many books and articles on climate, feminism and human rights. And says she finds a lot of value in taking the long view on making progress.

Rebecca Solnit: I think if I have a superpower, it's slowness, which means that I see long... stretches of time, which lets you see change. And one thing I run into a lot with climate is people often conflate impossible with unimaginable. Nobody in 1973 could have imagined 2023, but everything good in 2023 is because somebody in 1973 or some past moment fought for it. It behooves us all to do everything we can towards that better future for human rights, for biodiversity, for 30 by 30, and beyond, and for the climate. A lot of despair, et cetera, comes often from people thinking that if we have, if we make demands of a government on Tuesday and they don't fall to their knees and say they were wrong and we were right and give us everything we asked for by Thursday, then we failed, and that's just not how change works, although it's how defeat works.

Ariana Brocious: Rebecca also talked about why the white, western world can't just give up on addressing climate disruption:

Rebecca Solnit: I wrote an essay last year called Despair is a Luxury because for most of us giving up, at some level we secretly know that we can give up and our lives will still be relatively comfortable and safe.

Ariana Brocious: It's easier to give up.

Rebecca Solnit: Yeah, and so what you're really doing is giving up on behalf of people. You're saying, let those kids starve. Let that ice melt. Let those storms destroy the crops of those people in Central America. Let you know we're you, we, we who are relatively comfortable, safe, affluent, and therefore powerful, I think have no moral right to give up and we're giving up, you know, to let other people die first, other people lose first, other species lose first, I don't think it's ethical, and I think the facts say there's a lot worth fighting for now, and fighting for it is a really good way to live.

Ariana Brocious: I've read a lot of Rebcca’s work, and one concept that really resonates with me comes from book she wrote called “A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities that Arise in Disasters.” She explains that in spite of what we may think, true community spirit and belonging and mutual aid emerge in our times of greatest need. And that’s especially powerful considering our need for real resilience in climate disruption and disasters.

Rebecca Solnit: In order to do what the climate requires of us, there's a lot of very practical wonky stuff. You know, and very physical stuff. We need to electrify everything. We need to change how this, what the world runs on. But I also think that we need to change our imaginations, our values, our relationships. What's encouraging about how people respond to disasters, you see this. deeper sense of who we are and what we really want, who we could be. And I feel like we have to escape from consumerism. We have to escape from the kind of loneliness and isolation that Silicon Valley and a lot of other structures in our society have helped create. We have to feel that we can have an age of abundance, but abundance will be in confidence in the future and the society we live in. confidence in our institutions and each other, a sense of belonging, um, a quality of life that will lie in our relationships to other human beings, other species, the natural world. And so I feel like what disaster shows is that this is who we can be. It kind of shows a way forward, but we need to change the stories we tell about what a good life, a good society, and wellbeing look like as well.

Greg Dalton: I think that is a very powerful concept and one I’ve heard from other climate leaders– this idea of framing our future as one of abundance, not scarcity or limitation, which makes us selfish and scared. I had many impactful conversations this year. One that I continue to think about was with Reverend Lennox Yearwood, CEO of the Hip Hop Caucus. Early in his life he was active in environmental and social justice, but moved into climate after witnessing Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath.

Rev. Yearwood Jr.: Hurricane Katrina impacted me personally because I had a lot of friends in New Orleans and seeing them, well I think anybody, seeing anybody drown and suffer, I don't care if you knew them or not, it's going to impact you, but for me personally knowing those communities, knowing folks in the 7th Ward and the 9th Ward and then seeing the pictures and seeing where the water was, clearly, you realize that if the water was that high, people, could not survive that. And then you just realize that, wow, there are just so many people who are literally dying before our eyes on TV. Something must be done about this. And that was when I guess we sprang into action. at Hip Hop Caucus. We immediately had our networks together from the past election cycle, and people were being bused all around the country. So because of those networks, people were able to then connect with people. And then we just went right to work, and we haven't stopped since. I mean, I had a good friend who lived on Derjewan Street, Mama D. An amazing, beautiful, Black woman with these long, gray dreadlocks, and she lived on Derjewan Street. Pretty middle class community, but a community that was built on the backs of Black people fighting for, just dignity. And why I bring her up now is because when she stayed home, she didn't leave like many people could have, she could have left, but she stayed home and her neighbors, mostly older Black citizens who had to ride on the back of the bus and drink from the segregated water fountains. She stayed around, you know, she was in her own sixties and seventies at the time. And as her neighbors, grandmothers. and grandfathers begin to float down the street. She would go out there and catch them and tie them to the tree in front of her house. And that, for me, is why we do this work. Because no one, and I mean no one, should have to catch their neighbors floating down the street and tie them to a tree. And so for me, since that time, we, Hip Hop Caucus, created the Gulf Coast Renewal Campaign and have been working to stop, literally, anywhere, black or white, Republican or Democrat, neighbors from floating down the street.

Greg Dalton: That’s such a powerful story, reaching out to neighbors floating down the street, saving them and bringing them in. Reverend Yearwood is such a unifying force and such a compelling presence in the conversation.

Rev. Yearwood Jr.: We have a movement that puts people into buckets. They say, okay, if you're environmental justice, okay, well then go over here. That's where the Black, brown, and indigenous people go. If you're a young person, then go over here with Greta and Thunberg and other groups like that, and y'all stand over here. If you're from Appalachia over here, you're from the Arctic over there. And that is ridiculous because the entity that we're trying to stop and curtail the fossil fuel industry is not in buckets. They are not siloed. And so I'm not sure why we ever thought a siloed, segregated, climate movement would be successful, but it's not. And so I think that for me, I am in essence, a silo breaker. And so I work to break those silos to bring us together so we can be successful.

Greg Dalton: He works closely with former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who I don’t associate with hip hop, seem to be an odd pairing, but Rev. Yearwood is frank about the possibilities Bloomberg’s philanthropy provides:

Rev. Yearwood Jr.: David needs some, some stones. Cause we definitely fighting some Goliath. So if Mr. Bloomberg can provide the resources for a few folks on the frontline and first line communities have a few stones in their slingshot, then we're all for that. I understand. I'm going to be very clear. I understand what white supremacy is. I'm very clear on white privileges. But I'm also very clear that we are in a crisis, and we're in a crisis that can literally have extinction-level type events. And because of that, that means that we have to work together.

Greg Dalton: Rev and I talked about how the climate movement needs better storytellers to get the attention of folks across all interests. Take the benefits of electric vehicles over gas ones, for example.

Rev. Yearwood Jr.: There's different ways of telling the same story. I mean, if one person is saying that, Hey, you can plug in and save the planet. And that's a great story. And we need that story. Other story could be like, man, this EV is super dope and it goes really fast and it's a lot of fun to drive that may turn different people on. Sometimes, you know, you got to make things a little sexy, right? I mean, that's what's important also. I think that, I think people need to see it this differently. And that's why I think culture is so important, food and fashion. and how we view things. And also I think the movement had a tendency to only create the deep end. And that's, this is one of my things where everybody has to go to the highest diving board and leap off into the pool, into, you know, 15 foot water. The pool, though, should have two ends. It should have the deep end, which is important, but it should also have this shallow end where the babies can get in and in their little diapers, and they can play around in the water. And that's the same pool, the same water, but it allows for everybody, the babies on one side, but also those who want to dive off the deep board on the other side to be all in the same pool. I think the movement doesn't understand that. I think they just want to create this, the deep end of the pool, but you need to create the shallow end so folks can come in and learn. And I think that's what the Hip Hop Caucus is doing. They're creating a pool, the same water, same pool, same thing, but it allows for different people at different levels to feel comfortable and be in the pool at the same time.

Greg Dalton: I was awed by Rev. Yearwood’s dedication and willingness to give everything he has to the climate cause. Especially in spite of the fact that he feels his activism puts him at increased personal risk of violence.

Rev. Yearwood Jr.: I have children and I have a family and I have friends and so no doubt about it, I would love to be here in old age. But if someone feels that I am in the way they need to harm me, my goal is just that the next one will pick up the baton and run very far with it so that we can have clean air. And clean water. That's the calling sometimes that you have as an activist. You have to make that. And that's where faith comes in, for me. You know, you have to have a strong faith. To believe that it's just not you. That it's something bigger than you. And that's something that will carry on this fight. And that one day, and at this time, my goodness, with all that's going on and so much pain and so much trauma and so much hurt, you just got to believe that one day, the more that we keep fighting for justice, one day as humans, we will come together and we will make this planet a good place.

Greg Dalton: Are you saying you're willing to give your life to this cause?

Rev. Yearwood Jr.: I am more than willing to give my life to this cause because there's a righteous cause and there's a cause we're fighting for. And I know that without clean air and clean water, the next humans don't succeed. And so at some point in time, this is a temporal state regardless. And you know, I'm not going to be here forever. I’m okay with that. To know that the next generation, the same way, the exact same way that there were those who were on the plantations, there were those who were on the slave boats, there were those who were on the underground railroad, and they gave their lives so that a little black boy from Louisiana can work with a former Jewish mayor from New York to make the world better.

Greg Dalton: That’s a great way to wrap up the show, and this year, illustrating how we can reach across divides. Different kinds of people can find common cause. We have more in common than we often realize.

Ariana Brocious: It’s so true. And this episode helps remind us of the innumerable people out there who are working on climate from all different sectors and places around the world, which is an inspiring and hopeful place to end 2023. And we have lots more work ahead in 2024.

Ariana Brocious: You can listen to the full versions of all the episodes we mentioned in today’s show. Find us on your favorite podcast app or at climate one dot org.

Greg Dalton: Climate One’s empowering conversations connect all aspects of the climate emergency.

Ariana Brocious: Climate One’s empowering conversations connect all aspects of the climate emergency. To hear more, subscribe wherever you get your pods. Talking about climate can be hard-- AND it’s critical to address the transitions we need to make in all parts of society. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review.

Greg Dalton: Brad Marshland is our senior producer; Our managing director is Jenny Park. Ariana Brocious is co-host, editor and producer. Austin Colón is producer and editor. Megan Biscieglia is our production manager. Wency Shaida is our development manager, Ben Testani is our communications manager. Our theme music was composed by George Young. Gloria Duffy and Philip Yun are co CEOs of The Commonwealth Club World Affairs, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.