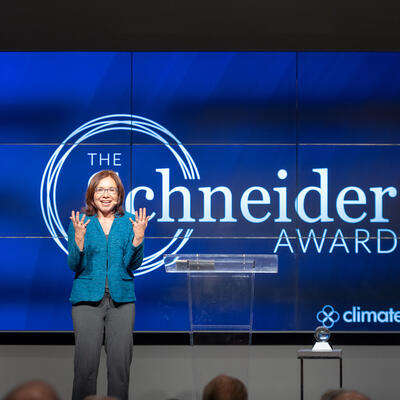

Leah Stokes: 2024 Schneider Award Winner

Guests

Leah Stokes

Rebecca Solnit

Summary

Every year Climate One grants the Stephen H. Schneider Award for Outstanding Climate Science Communication to one scientist. This year’s recipient is Dr. Leah Stokes. She’s an expert in climate and energy policy and an associate professor at the University of California Santa Barbara. She’s also the co-host of the podcast “A Matter of Degrees.”

“I view the climate problem as a fossil fuel problem first and foremost, that's my orientation. I work on the energy system. This whole problem began when we started to dig up carbon stores from underground and combust them, burn them, put them in the air and the water, in the active cycle. And so that's the part of the issue that I tend to focus on,” Stokes says. She doesn’t think guilting or shaming people about their use of fossil fuels is a useful or fair strategy.

“My attitude is that we were all born into a fossil fuel based energy system. Nobody chose that,” she says. “And so the work of our life is not to make people feel bad that they were born into a fossil fuel based energy system. The work is to change that.”

Stokes is a leader in connecting regular people with the nerdy world of the electric grid and energy policy. She is a go-to expert who often appears on CNN, BBC and NPR. She also had an influential role in shaping national energy policy such as the Inflation Reduction Act, the biggest economy-wide step the US has ever taken toward addressing climate disruption. Outside of academia, she’s involved with Rewiring America, helping people figure out how to get fossil fuels out of their lives and making heat pumps sexy.

“As I've gotten more involved in clean electricity and electrification advocacy…what I've started to think about is not how can I make my impact as small as possible, like a carbon footprint, trying to shrink, but actually how can I make my impact as big as possible by joining with others in campaigns to try to change policies and laws so that we're not just trying to make marginal, incremental improvements on a fossil fuel-based energy system, but actually change the system towards clean electricity and electrification.”

Episode Highlights

01:40 – Leah Stokes’ start in climate work

05:00 – Durability of the Inflation Reduction Act

10:30 – Making climate activism more inclusive rather than using “purity tests”

14:15 – Reflecting on the results of the November election

17:30 – Republicans will start next session with small majority in the House of Representatives

22:30 – Working on ways to decarbonize low temperature processes

25:00 – Role of the Green New Deal in spurring serious climate policy

28:30 – Action at a state level rather than national level

34:30 – Approaching climate work emotionally

38:00 – Rebecca Solnit on the power of slow change

42:30 – Climate defeatism versus climate denialism

46:15 – Better celebrating climate victories

49:00 – Finding solace and community in the worst of times

Resources From This Episode (2)

Full Transcript

Note: Transcripts are generated using a combination of automated software and human transcribers and may contain errors. Please check the actual audio before quoting it.

Greg Dalton: I’m Greg Dalton.

Ariana Brocious: And I’m Ariana Brocious.

Greg Dalton: And this is Climate One.

[music change]

Greg Dalton: This is one of my favorite times of the year. Not just because we slow down, take a break and enjoy food and family time during the holidays. But also because we take a moment to recognize someone in the climate communication space who is just really doing great work.

Ariana Brocious: Every year Climate One grants the Stephen H. Schneider Award for Climate Communication to one scientist. This year’s recipient is Dr. Leah Stokes. She’s an expert in climate and energy policy, and an associate professor at the University of California Santa Barbara. She’s also the co-host of her own podcast, A Matter of Degrees.

Greg Dalton: Leah is a leader in connecting regular people with the nerdy world of the electric grid and energy policy. She is a go-to expert who often appears on CNN, BBC and NPR. She also had an influential role in shaping national energy policy such as the Inflation Reduction Act, the biggest economy-wide step the US has ever taken toward addressing climate disruption. Plus, she’s fiery... and has been known to drop the occasional F bomb, which she managed not to do on stage with me at the Commonwealth Club. We kept it clean and classy.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, she's not your typical academic. And outside of academia, she is involved in helping people figure out how to get fossil fuels out of their lives and making heat pumps sexy. And she’s been doing this work for twenty years.

Leah Stokes: I began working on climate around 2005. This is also when Hurricane Katrina happened. And, the next year, 2006, An Inconvenient Truth came out. And that was such an important film to wake up so many people to the climate crisis. And I saw it in person at the University of Toronto, but the thing I remember the most from that experience of watching the film was actually the credits. I don't know if people remember the credits from An Inconvenient Truth like I do. But it's a black screen, as credits are, with white text. But rather than just saying, you know, here's who directed it and here's the thing, it said, You can stop the climate crisis. Oh, this is when I leaned in and got pretty excited and it said you can reduce your carbon emissions In fact, you can even reduce them to zero and then what was the secret? Recycle. And turn off the lights and change your light bulbs and you know, that was the moment then. It's not a criticism of anybody who wrote those credits. I doubt it was Al Gore himself. But that era of how we thought about climate action, what I was doing at that time, too, was getting students to turn off the lights to reduce energy. If we just use a little bit less fossil fuels, then yay, we're solving the problem. And, I think that that's not really true, unfortunately.

Greg Dalton: Well, and there's, but there's a story underneath that, which is, a couple years before that, it was British Petroleum, which came up with the idea of the carbon footprint calculator on their website, and they invested a hundred million dollars. So it might've been natural for people to say, what can I do? And there was a fossil fuel industry funded campaign to put that back on us.

Leah Stokes: Absolutely. And that's how it ends up in the credits of An Inconvenient Truth, right? And we all spend this period sort of trying to figure out how we can shrink our impact. And what I've really started to think about, as I've gotten more involved in clean electricity and electrification advocacy, which is a paradigm shift, right? It's not just, burn a little bit less fossil fuels. It's, get off of fossil fuels, move towards clean electricity and electrification. What I've started to think about is not how can I make my impact as small as possible, like a carbon footprint, trying to shrink, but actually how can I make my impact as big as possible by joining with others in campaigns to try to change policies and laws so that we're not just trying to make marginal, incremental improvements on a fossil fuel-based energy system, but actually change the system towards clean electricity and electrification.

Greg Dalton: Right. As Bill McKibben says often, the most important thing an individual can do is not act as an individual. Join with others. So you were very involved in the inflation reduction act. You know the biggest piece of climate legislation ever. I'd like to set the story and then dig into that a little bit with you. So Al Gore awakened many people. People realized that we needed an economy wide approach to climate change. It never really got to the level of national politics until say around the, the, the 2020 election. And suddenly we had Democrats, um, tripping over each other saying 1 trillion, no, 3 trillion. I think it got up to 16 trillion–

Leah Stokes: That was Bernie Sanders.

Greg Dalton: Right. And, and it was, so we had this competition for like, you know, to the top for them trying to outdo each other. Biden, the moderate, wins. He gets pulled a little bit more to climate because with Bernie, green new deal, you know, first there's going to be build back better. It's going to be hugely ambitious and then political reality sets in and it gets shrunk down into the Inflation Reduction Act where trillions become billions. Right and when it does get passed some people are like, “oh this is a disappointment. It wasn't as big as we wanted. There's a lot of stuff in here we don't like nuclear, hydrogen carbon capture. So my idea is that a lot of the things that are in there that Democrats and climate people initially didn't like are now what's going to keep it alive because those things are in there. If it had been what Biden really wanted. The new administration would be taking a sledgehammer. Instead they're going to be coming with a scalpel. So isn't that disappointment from some years ago a good thing now because this policy that you worked so hard on is more likely to live.

Leah Stokes: Yeah, well, the Inflation Reduction Act, it's really hard to estimate how much money will actually be. It only got harder after the election.

Greg Dalton: It's only two years in.

Leah Stokes: Yes, it's only two years in, there's a huge chunk of money that are grants, which is money that will hopefully disproportionately benefit lower income folks, communities of color, disadvantaged communities, that money will often flow through the states. So there are programs, for example, to help everyday Americans get a heat pump. For example, the state of California, as well as New York, have already opened up these programs that if you make a certain amount of money, you can go online and see if you can get a rebate back from the state to, you know, put a heat pump or heat pump water heater in your home. So those programs when the money is out the door and in the state coffers. It's not like the Trump administration can take that money back. The money that is harder to estimate and part of the reason why we don't know exactly how much money we'll spend is all these tax credits and there are a lot of them.

Greg Dalton: And there’s no ceiling on them, right?

Leah Stokes: There's no, these are uncapped tax credits. That's something that could change, the Republicans could decide to cap them. But that is probably not a very popular thing to do, because as a lot of different trackers have been showing, like, for example, the Clean Economy Tracker, three quarters of the money is flowing into Republican districts. So if you look at, for example, where these tax credits to manufacture batteries or solar panels are going, they're disproportionately going to Republican-controlled members of the house and Republican senators districts. And so why would the senators and members of Congress get rid of jobs in their own backyards, especially manufacturing jobs that, you know, provide good paying, you know, living wages to families that are, you know, theoretically voting for them. So those are the policies that are going to be fought over in the next probably two years before the 2026 midterms and my bet, I could of course be wrong, is that corporations are going to show up and say, we want these policies to stick around and, and keep them.

Greg Dalton: Well already, you know when Trump was elected the first time the auto industry was right out of the bat saying okay, We want to undo some of these things fuel efficiency standards that Obama put in place this time the auto industry saying hey that ev tax credit, We'd like to keep that in place. So the industry is in a very different place. Even some of the fossil fuel billionaires that are influential in this administration have made renewable bets. So you wrote a book on interest groups in the battle over clean energy. I'm curious what you see as kind of the shifting alliances because it's a real scramble going on. This is not 2016, it's not 2020. You know the U.S. Chamber’s in a different place, auto companies are in a different place. How do you see this shaking out or is it too early to tell?

Leah Stokes: Yeah. So this book that I wrote, it's called Short Circuiting Policy. It's an academic book, but a lot of practitioners have read it, which was shocking to me because when I was writing it, I thought it was the most useless thing I had ever done in my life. And why was I wasting so much time on this thing when the planet was on fire? But it turns out that a lot of people have read it who are activists because they find it useful. Because I asked the question of why do some laws continue on and why do others get rolled back? That's exactly the same question we find ourselves asking right now. Is this law going to continue on or is it going to be rolled back?

And one of the patterns that I talked about was interest group power. So basically if you have opponents, like for example, fossil fuel companies with very strong ties to the government who have a lot of money that they give through campaign contributions and they capture the courts and they capture the bureaucracy and they capture the public opinion you know, they can use that power to roll back laws or even just weaken them during implementation but if you start to have the clean energy industry have power in a similar way where they're well networked with, you know, members of Congress, with the executive branch, with the presidency, where they are influencing public opinion and influencing the courts, they can start to battle these opponents to the clean energy transition and, you know, people can have many legitimate feelings about, for example, Elon Musk. I'm sure many people do. But the fact is that he is a person who made money in not fossil fuels, but in solar and batteries and electric vehicles. That's a very different thing than, for example, during the first Trump administration, when Rex Tillerson got appointed to run the State Department.

Greg Dalton: And Tesla, Elon Musk make a lot of money selling carbon credits. So that's an incentive to keep the carbon markets in place. In his first speech after the election, President Obama said “purity tests are not a recipe for long term success.” So I'm curious what you think about that, and how that applies to climate, because sometimes there is a purity issue on the left about being vegans, and how pure people are, and we want these policies that are pure, and not, not compromised with fossil fuel interests. Is this a time for coalition building and questioning purity?

Leah Stokes: Yeah, I would call myself a progressive and, after the Inflation Reduction Act passed, there was a lot of conflict in the progressive part of the climate movement. And I, a friend of mine, Kate Marvel, who's a wonderful climate scientist, told me to go read Homage to Catalonia by George Orwell, which was a fascinating thing to read because basically you discover that the left is infighting and, you know, thinking that they are their enemy rather than, you know, the fascist. and that that's a tale as old as time, so to speak. And so we sometimes have this tendency to see people who are really close to us, who agree with 90 percent of what we agree with, but have some small difference, and view those people as the ones that we should attack or focus on and try to fix, as opposed to the people we maybe agree with 50%.

Greg Dalton: Freud talked about the narcissism of the small difference.

Leah Stokes: There you go, see, it's a tale as old as time. And, you know, in the wake of the, you know, presidential election in the fall, Representative Alexandria Ocasio Cortez, who I think is an amazing climate communicator. She talked a lot about how in this moment, what we need to be doing is building our coalition. We need to be bringing more people in. We can't be making people feel excluded, or if they're not perfect. You know, they're not vegan or they're not, biking everywhere they go because, I don't know, they've got kids in a minivan or something like that, that they are somehow excluded from our movement. –

Greg Dalton: But that's not a common view. There's a lot of righteousness and a lot –

Leah Stokes: Well, I'm with representative Alexandria Ocasio Cortez. If it's her view, I think she's rather right about that. We have to be building and bringing people in and that's what's going to make the climate movement succeed, but more broadly progressive movements.

Greg Dalton: Right, but we all practice this sometimes, this virtue signaling, like, oh, you eat meat, like, oh, you know, you can't be one of us.

Leah Stokes: Well, I view the climate problem as a fossil fuel problem first and foremost, that's my orientation. I work on the energy system. This whole problem began when we started to dig up carbon stores from underground and combust them, burn them, put them in the air and the water, in the active cycle. And so that's the part of the issue that I tend to focus on. And per your point about shaming, it's not about telling people you're a bad person if you burn fossil fuels. My attitude is that we were all born into a fossil fuel based energy system. Nobody chose that. You weren't like, hey, I'm a one year old baby, and I choose a fossil fuel based energy system. You were born into that. Even my grandparents, my grandfather, who's still alive, and he's, um, I think 96, he was born into that system too. You can actually see some of the anthropogenic signals in the Earth system going back to the early 20th century. And so the work of our life is not to make people feel bad that they were born into a fossil fuel based energy system. The work is to change that. The work is to make it so that there is a generation in the future that is not born into this fossil fuel based energy system. So shaming people and making them feel bad, That doesn't really help with the problem, does it?

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to a conversation with this year’s climate communication award winner, Leah Stokes. When we come back, we’ll have more on what climate policy and action might look like under the second Trump administration. Stay with us.

Ariana Brocious: Help others find our show by leaving us a review or rating. Thanks for your support!

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. Today we’re featuring my conversation with political scientist and energy expert Leah Stokes. She’s this year’s recipient of our annual Steven Schneider Award recognizing excellence in explaining complicated science and policy to everyday people. Leah Stokes says the American punditry has overanalyzed the results of the November election.

Leah Stokes: Every time we have an election, a lot of ink gets spilled about why did it go that way. It's over interpreted. I mean, I'm a political scientist. I have some political scientist friends in the room. I imagine they're going to agree with me. There's a lot of fundamentals that drive, from a political science–

Greg Dalton: There's a whole industry of like, you know, feeding our anxiety.

Leah Stokes: The political science basics of what we would say is that, It's sort of like what Bill Clinton said, it's the economy, stupid, right? This was an inflationary period. It really was a COVID election in many ways, a pandemic election. A lot of people, lost businesses or lost jobs. There were really big impacts on their personal lives because of the pandemic and the lockdowns and people had feelings about that. You know, that the impacts of those decisions were not equal across society. Some people could stay home and keep their jobs, you know, and others could not. And so a lot of people were really angry and then they were watching the costs of everyday goods in their lives go up and inflation is really unpopular. People don't like it when a dollar is worth less than it was yesterday. And so you can look across the world and see that almost, you know, without exception, the incumbent party has been voted out this year. And when it comes to climate change, I certainly don't think that this was an election where, you know, people were backlash against the climate policies of the Biden Harris administration. People sort of thought, yeah, that's fine. There's a lot of manufacturing jobs. That sounds good. It really wasn't the central driver. I really think pandemic and the inflation were.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, even, you know, gas prices are often factors in presidential elections. Not so much this time, right? I mean, you know, inflation writ large, yes. But not so much. So there were a lot of people, you know, climate people who were like, Oh my gosh, we're toast. If this goes the wrong way, do you think there was too much fear? Was there hype about the climate implications of this election? Cause you are more concerned about immigration implications than climate.

Leah Stokes: Well, what I will say is that when you have an incoming president elect who's talking about deporting 20 million Americans or undocumented people in this country, oh, or maybe maybe even citizens, I don't know how broadly they're planning to go with this. Ending birthright citizenship, which is, you know, required under the Constitution.

Greg Dalton: 14th amendment.

Leah Stokes: Some of these things, to me, are very concerning. and I think that there's been a lot of focus, too, both from the President elect, as well as many of the people he has appointed, on that specific issue. By contrast, there isn't as much focus on the people that he's appointed on repealing everything we've done with clean energy investments. You look at somebody like newly elected Senator Curtis from Utah, who had been in the house, he lives in an electrified home. This is a Republican –

Greg Dalton: Oh, I have talked with him about that. He has a climate friendly doggy door that he's very proud of that is like heat insulated and he showed me photographs. You can look on YouTube. He's kind of a nerd about this stuff.

Leah Stokes: and he ran a conservative climate conference just at the tail end of the election in Utah and brought a lot of Republicans there. And he's already spoken out about what they plan to do with the energy parts of the Inflation Reduction Act. And he said, look, we might make some tweaks here and there, but we're not going to repeal the whole thing. And keep in mind too that the House, the House of Representatives is likely to be about 217 to 215 members Republican controlled for the first 90 days, because Trump has appointed three people to his administration, shrinking the Republican majority. And if you look across the House of Representatives at any given time, somebody is sick, or they've died, or they've had a kid, or they'd like to run for the governor of New York, hypothetically.

Greg Dalton: Or maybe gone to jail. Yeah, yeah.

Leah Stokes: Yeah, they've gone to jail. So, I mean, that is a razor thin majority. So, when you look at the things that are being said, the focus, it seems like, is really going to be on immigration. I think that those first 100 days, keep in mind, the first 90, they're gonna have a two seat majority in the House, it's gonna be hard to be like, you know, the number one thing that we should do is get rid of jobs in Republican House members districts. I don't know, that wouldn't be on my top to do list.

Greg Dalton: Right and a lot of the concern is about about expanding supply more drilling, etc, what's the worst case for that? I mean, I realize you're a political scientist not an economist but expanding supply depresses prices. It's a global commodity. It's not you know, it's not like more is going to be burned, right? but it seems like the climate people might be dare I say over worried kind of, you know, hyperventilating a little bit about more drilling, etc It's bad if it's in your neighborhood for sure and you know sensitive habitat, Indigenous lands for sure, but, you know, just because there's more supply it just depresses prices, you know, pushes some negative economic pressure on the industry, which is not necessarily bad.

Leah Stokes: Yeah, well, another interesting thing is that President elect Trump has been talking a lot about tariffs, right? And putting them on Canada and Mexico, for example. And Canada, where I'm from, I'm also Canadian, supplies a lot of oil to the United States. And there have been some economists suggesting that that will massively reduce gasoline prices, particularly in the Midwest. If he does this, that will also be very unpopular. So, yeah. I think that there will be some supply side policies that I don't agree with. You know, you have to wonder about, for example, LNG export terminals. The Biden administration could, for example, reject, a bunch of LNG terminals

Greg Dalton: Liquefied natural gas going toward Europe to help them get off Russian gas.

Leah Stokes: So they could, they have a review going on right now at the department of energy where they could reject a bunch of terminals. I hope they do that as some of the last executive actions of the Biden administration, but you can imagine that the Trump administration will try to do more fossil fuel extraction. The president doesn't have a huge amount of power over the amount of fossil fuels that are burned. Oil is a global commodity. It is priced globally and the amount that is produced at any given time is largely determined by, you know, what that global price is. And so President Biden, for example, when he was first in office, did actually honor his campaign promise to stop new leasing on public lands of fossil fuels. Unfortunately, a Trump appointed judge overturned that about eight months into the administration. But, you know, despite the things that he tried to do to rein in the amount of fossil fuels that were being produced, it was actually the most fossil fuels produced in American history. And people really blamed him for that. But that was because the fossil fuel, global prices were pretty high at the end of the Biden administration.

Greg Dalton: Right, and he–

Leah Stokes: So these are difficult things for a president to control a lot, you know, when it comes to production.

Greg Dalton: I mean, he also came in to restore the rule of law and those oil companies had contracts and leases that were legally binding. So you don't want a president to come in and say, you know, Oh, you're oil. So your contracts don't matter. I mean, he was following the law.

Leah Stokes: Yes. That's on the permitting side. Yeah.

Greg Dalton: So things like willow in Alaska, there were contracts. So one of the things that I did, you Let me just say it's comforting to talk to you because you seem less freaked out about the election than with other people I talk to.

Leah Stokes: I don’t know if I’m less freaked out. I myself am an immigrant to this country so I haven’t been a citizen that long.

Greg Dalton: If things get bad you could go back home, is that what you're saying?

Leah Stokes: No I’m not saying I could leave, I’m saying I’m concerned that we seem to have an incoming president who doesn’t think citizenship is real. And that is disturbing.

Greg Dalton: So there was a big effort in 2009. Obama passed health care, didn't really force the Senate to go all in on climate, was criticized for that, and think these things come around about every decade. And what happened in 2022, the IRA, there was like 10 years of work foundation that had gone into that. So what you're saying is that the foundation is being laid now while everyone is depressed and drinking too much, et cetera, you know, that they're looking at 29 to build that infrastructure for that next step.

Leah Stokes: Yeah I don’t really drink so I’m already thinking about the next climate bill. And for example, we don’t exactly know how to decarbonize the industrial sector. People have lots of ideas, don’t get me wrong, but with my colleague, Eric Massonet, an amazing engineer and a leading expert in industrial decarb. Uh, we actually have an episode of this coming out on our podcast, Matter of Degrees, but we're thinking about how do we take low temperature processes. So these are things like making a bag of potato chips or pasteurizing milk, which we'll hopefully still be doing, or you know, making cans of lacroix soda water. Right? How do we do that without fossil fuels? There are parts of our manufacturing base that are making things in this country. They are using fossil fuels and they don't have to because they don't actually need super high temperatures. So people think a lot in the industrial sector about steel and aluminum.

Greg Dalton: That aluminum Lacroix can.

Leah Stokes: Yes, and then also with cement. It's a byproduct. CO2 is a key part of the chemical reaction. But people think like, Oh, let's put a lot of attention on that. And they need to, too. Don't get me wrong. Thank you for everybody focusing on high temperature industrial decarbonization. But what about low temperature industrial decarbonization? How are we going to do that? We've got to figure that out. So we have a roadmap project right now trying to think about how we do that. How could we get some pilot projects going on in various states? We have to do that and we don't exactly know how from a policy perspective we can make that happen. So now is the time to think about what do we need to get done.

Greg Dalton: and get industry on board so they're not fighting this.

Leah Stokes: Yes. And give them carrots, you know, rather than just sticks. I mean, I am very pro carrots. So people criticize the inflation reduction act and they say, well, there was no carbon tax and carbon price. And if we had gone a more Waxman Markey stick approach with that bill, I don't think in this moment, I'd be like, Oh, I think a lot of it's going to stick around because people would be saying, Oh, that's why everything's expensive. We have got to repeal that. Going this more incentive based carrots approach is very important.

Greg Dalton: Centrist. And so you're saying let's go durable rather than pure and ideal. So green new deal might be the virtuous path. It ain't gonna last, you know, it's not gonna be durable over time change of power in Washington.

Leah Stokes: Yeah, I don't want to criticize the Green New Deal or people who are dreaming big. You know, I think that is very laudable. And I think the young Sunrise activists, who I know a lot of, who did that sit in, changed everything. I really do. I think that having a vision, a positive, hopeful vision of what we want, was a huge paradigm shift from the dominant narrative in climate policy, which was just make things more expensive and it'll change everything and make things better.

Greg Dalton: Price on carbon.

Leah Stokes: Price on carbon or bust. I mean, that wasn't a hopeful, positive vision. So I do feel that the Green New Deal is a big idea, was a big change. And the way that that went through the sausage making process of the United States Senate was the Inflation Reduction Act came out the other side. But you know, Sunrise, Representative Alexandria Ocasio Cortez Senator Markey, all the people involved in the Green New Deal deserve a lot of credit for what eventually passed in the Inflation Reduction Act.

Greg Dalton: So, you need that big aspiration and eventually it gets down to something else when it goes, goes through. You know, after, um, Trump's first election, people took to the streets, marched for science, marched for women, putting on certain types of hats.

Leah Stokes: Pink ones, I think, yes.

Greg Dalton: Yes. You know, this time is different this time. There doesn't seem to be,

Leah Stokes: We’re tired, is that what it is this time?

Greg Dalton: So is it, is it wisdom or resignation? Hey, that like, Oh God, you know, or is it, I mean, yeah, is it resignation or it's like, Hey, you know, I mean, I interviewed Jane Fonda. She said like, you know, that big march didn't really create lasting change. It's a lot of work. Felt good for a few days. We feel powerful. And then what change really happened? So as a political scientist, what do you see about the response now? Is it more technocratic? It's more, you know, mass movement in the streets? Is it surrender and normalization?

Leah Stokes: Oh gosh, I hope it's not that. I'll talk about Rebecca Solnit's work. She wrote a book called Hope in the Dark. It was about trying to think about glimmers of possibility, even when things are not going in the direction that you want them to be. I don't know how anti democratic the next two years, let alone four years, will be. Because keep in mind, in two years, there will be a midterm. And again, as a political scientist, we have this thing called a thermostatic response. Meaning, people tend to go in the other direction after we go in one direction. So, we had 2016, which Trump was elected the first time. But then the 2018 midterms is a huge progressive swing where the squad first gets elected, the green new deal starts happening. You get this counter, this pushback.

Greg Dalton: Especially when right now we have one party control of all three branches that swing could be–

Leah Stokes: Exactly. So really in the next two years that will be this critical time period to see how far we undermine Democracy in this country. I think a lot of people are ready to push back Whether that looks like marching in the streets or you know challenging things that the Trump administration does legally as, for example, Earth justice did so much during the first Trump administration. I don't know. But I do think that people are tired is what my general hypothesis is, right? We've all gone through this pandemic. It's had huge impacts on a lot of different people. And I don't think that means that people are resigned. It just might mean that the way we resist or the way pushback happens is slightly different.

Greg Dalton: And I think it might be more local because I think the national is so toxic. People are just sick of the toxicity. Can be less toxicity on the local level where things are like, I know you because you're in my city or my state. And there's, you know, mayors can be less partisan or polarized because they have to like, pave the streets and get the garbage collected. So that's one thing and that's also, you know, often there's a swing when Washington goes anti-climate. There's a swing back to the states and like cities and states matter. That's where the carbon is. You know, most energy is, you know, but best is delivered through, you know, wires and cables that are regulated at the state and local level. So maybe it's more that's where people focus rather than Washington, the swamp in Washington.

Leah Stokes: Maybe. You know, this year, for example, in California, the cap and trade program, it raises a lot of revenue. And in the past that money has gone to high speed rail, which you may notice, uh, doesn't exist yet, but maybe someday. They're starting to think about how they wanna spend that money. And what if they spent it on some of the ideas that we've just seen federally? So, for example, helping everyday low income people in California electrify their homes or their apartment buildings. What about getting heat pumps for schools, as the great group Undaunted K 12 has been working a lot on? You know, what about, um, getting more money to do solar community microgrids in the cities and counties across the state? That's an opportunity just in California this coming year to do a kind of, you know, Green New Deal Inflation Reduction Act investment program towards building what we want to see. And this happens in states all the time. For example, a colleague of mine at Rewiring America worked in Colorado this past year to get a huge, hundreds of millions of dollars, in the Excel electric utility territory to help people electrify their homes. That was actually more money that they helped get through this state action than the federal investments through the Colorado rebate programs for homeowners. So, you know, there's always stuff to be doing when it comes to climate policy. I like to say I have like permanent employment for the rest of my life because this problem is so big and vast and endless. Unfortunately, I don't want that, to be clear. I would love to solve the climate problem and do more crochet or something like that.

Greg Dalton: Yes. Yeah. Well, I always tell young people who come and say want to get into climate. Like, yeah, it's a growth industry. There's going to be more jobs working on this. And you know, so those things, heat pumps, induction cooktops, electrifying our homes makes a lot of sense as a way to improve your life and clean up the atmosphere in our air. And in much of California, the cost of electricity has risen 50 percent in just three years. Uh, the increase has been much less in places like Sacramento and Los Angeles, which have nonprofit electric companies, but rising electricity prices are really starting to undermine this electrification and change the narrative. I've driven electric car for 10 years, I could always confidently say, electricity is, whatever it is, I can't do the math of, you know, kilowatt hours to miles per gallon. Electricity will be cheaper than gasoline. It's getting harder to say that now.

Leah Stokes: Well that isn’t actually true for cars in California. So you still save money. It's something like a dollar, two dollars per gallon if you’re going to take the kilowatt hour to the oil. So the EVs you still save money, and there’s still a good payback in every corner of the country including in Hawaii, which is interesting because they just burn oil for a lot of their electricity. Um, but anyway,

Greg Dalton: But you take the point that rising electricity prices are a problem.

Leah Stokes: It's absolutely a problem. I mean, SCE and PG& E and –

Greg Dalton: These are California utilities.

Leah Stokes: California utilities have been jacking up electricity prices way too much and unfortunately, they've been scapegoating little parts of the electricity bill where we like, have little bit of money to like, help a school electrify their, you know, HVAC or help low income folks do an energy efficiency thing on their house.

Greg Dalton: And it's not just California, it's Oregon too. It's other places.

Leah Stokes: Yes. But that's not the fundamental driver. If you start looking at profits, the amount of profits that these electric utilities have been taking. I mean, they're astronomical. If you look at the amount of what we call gold plating, which is over investing in certain parts of the energy system, because utilities are monopoly companies, if they can spend more money, they can charge all of that to the state. And then they can put more profit on top of that. So from my perspective, what we really need is better regulators in the state of California, who are pushing down those electricity prices, not, you know, taking away an HVAC system from a school because it costs somebody like one dollar on their energy bill in March.

But we also have to think about why are gas prices so cheap too? You know, gas isn't really cheap. People are not paying the true cost of what the gas system is. Now in some parts of the country, not as much in California, but in many parts of the country if you electrify your home you do save money and the people who save the most are people on delivered fuels. So if you have, you know people in for example, Maine and Massachusetts who have oil or propane, parts of the Midwest. If you switch to heat pump, heat pump, water heater, you save money.

Greg Dalton: So if fuel comes to your house in a truck,

Leah Stokes: You’re going to save thousands of dollars a year. Yes. This is what rewiring America has calculated. But also if you put solar on your roof and you electrify your home, you do the whole thing, which is what I have done. Then the payback period tends to work better because you're generating that cheap, clean electricity yourself and your electricity bills going down. So. We have to get this right though because we can't have it be that, you know, burning a poisonous gas in your home that is literally leaking carcinogens, benzene into your kitchen is better and cheaper somehow than, you know, induction. You know, just using the power of magnets to boil some water very fast as I now do. So we have to get that right.

Greg Dalton: So this is an economically rational argument. You said you quoted Bill Clinton is saying, it's the economy, stupid yet, you also have an undergraduate degree in psychology. And I think that we often. Policy nerds like us and, you know, talk about, you know, and people in climate say science, facts! But doesn't that miss like part of you know, human reality? We're emotional creatures who use our brain to justify the emotional decisions we make? So I want to talk about the side of this transition that's scary to a lot of people, uh, particularly if you're in a fossil fuel state, um, Or there's it's it's talked about in very fearful terms. Oh, the left is exaggerating climate. You're always the sky is falling. You're a bunch of hysterical people. Talk about that part. That's not the rational brain that talks about kilowatt hours, but just climate as an emotional opportunity or threat.

Leah Stokes: Yeah. So this podcast that I run called a Matter of Degrees with Katherine Wilkinson, she's a really good counterbalance to me because she's a very heart forward person, really emotions and –

Greg Dalton: She is lovely that way.

Leah Stokes: Yes. And so she tends to bring that energy. She, you know, co edited the book All We Can Save with Ayana Elizabeth Johnson, and, you know, they put poetry in the book. I mean, it's beautiful. And so, that is a way that she tends to approach these issues, and I think that is a really important thing.

Greg Dalton: She brings her whole self.

Leah Stokes: Yeah, she does, and I do too. It's just that myself happens to like kilowatt hours and wonky subjects. As well as Mary Oliver poetry. I think that we do have to bring that, and I think that's why when we were talking about shaming people, that isn't really the way that I tend to go with my messaging.

I think that too much of the environmental movement has been focused on sort of individual action and making people feel that they are not passing a purity test. Shame is not a great emotion to like bring people to your party, right? Like people don't like feeling shame. It's probably one of the worst emotions that we experience. Exclusion, shame, othering. Right? And so I think that we have to build a movement that calls people in, that makes them feel part of something fun. It's more like throwing a party, right? Rather than saying to people, you're not invited. So that's really the energy that I think will help propel the climate movement into, you know, more policy wins, which is always the best thing to have when you get up in the morning, get another policy win.

Greg Dalton: Leah Stokes is a political scientist and energy expert and associate professor at the University of California Santa Barbara. She’s this year’s recipient of our annual Steven Schneider Award recognizing excellence in climate communication. You can find a link to her podcast, A Matter of Degrees, in our show notes, along with more information about past winners of the Schneider award. There are fabulous storytellers in there. Check them out.

Ariana Brocious: Coming up, I talk with author and activist Rebecca Solnit about how we have to resist allowing climate despair to consume us. Plus, how to get better at recognizing victories, and celebrating them.

Rebecca Solnit: A lot of victories look like nothing. The forest wasn't cut down, the toxic incinerator wasn't built in the inner city neighborhood, so the kids didn't get asthma, etc. So a lot of times if you're looking for victory, it literally looks like nothing, it's a thing that didn't happen. But a lot has happened and is happening.

Ariana Brocious: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

This is Climate One. I’m Ariana Brocious. In 2023 I had the opportunity to speak with author and activist Rebecca Solnit live on stage at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco. We had a wide-ranging conversation, and much of it centered on climate change — how our understanding of it has evolved, how we can handle the range of emotions it brings with it, and how to keep optimism alive.

Rebecca Solnit: I think if I have a superpower, it's slowness which means that I see long... stretches of time, which lets you see change. And one thing I run into a lot with climate is people often conflate impossible with unimaginable. Nobody in 1973 could have imagined 2023, but everything good in 2023 is because somebody in 1973 or some past, um, moment fought for it. And I like 1973 because you can see the most mainstream narrative is that the Civil Rights Movement, which means the Black Civil Rights Movement, was really in decline at that point, arguably. You could debate that. But the Native rights movements were really surging. The women's movement was surging. Gay rights were really beginning to gather force. A disability rights movement was happening. And the environmental movement, which was something really different than the earlier conservation movement was also really beginning to do stuff and even the language for thinking about all these things had to be invented.

And I know feminism best in some ways. Words like domestic violence and marital rape weren't concepts or terms people had. So you could see they made mistakes, they stumbled, They didn’t quite know what they wanted and what they were doing. But so much good stuff comes from it. So I feel for 2073, it behooves us all to do everything we can towards that better future for human rights, for biodiversity, for 30 by 30, and beyond and for the climate. You can't see the future, but you can learn the shape of change from the past. And to see it also means seeing indirect consequences and other impacts. A lot of despair, et cetera, comes often from people thinking that if. You know, like if we have, if we make demands of a government on Tuesday and they don't fall to their knees and say they were wrong and we were right and give us everything we asked for by Thursday, then we failed and that's just not how change works, although it's how defeat works.

Ariana Brocious: So a lot has changed since you entered the climate movement or the environmental movement. How do you evaluate the progress that's been made when we look back and we've talked about some of these, you know, the recent bills, but when you look back on maybe the last 20, 15, or even five years, what we've done, and also considering that. As there's been progress, there's been continued, um, acceleration of climate impacts. You know, last year was the hottest, this is the hottest year on record, and that keeps happening.

Rebecca Solnit: Thank you for asking me a slowness question, a long term change. I think if you told people where we were with renewables and how powerful and engaged the climate movement is, and how much the public is engaged compared to where we were 10 years ago. I don't know how much people would believe it and I think some of the problems we still have are that people's, a lot of people get this vague understanding and don't get updates. The idea that we don't have the solutions, that nobody cares, that the media is not covering it are all things that were reasonably true to say 15 or 20 years ago. They're completely inaccurate now. Everything is different. The early climate movement was polite. It was sort of requesting and kind of trusting governments and corporations to do good things. The idea that we had to fight them, blockade them, call them out. Um, You know, etc. I watched the founding of 350.org and watched it go from a kind of nice, polite organization to a much more radical one. We grew up in the, sort of, the age of fossil fuel, or is regnant and triumphant, and it's been completely normalized, and part of our job is to denormalize it.

Ariana Brocious: yeah, I mean the idea that, you know, it's a normal thing to turn on your gas stove and smell gas in your home that you're combusting.

Rebecca Solnit: Methane, which we now call methane, when we're telling the truth,

Ariana Brocious: kind of, when that change happened for me, I remember thinking it had been so normal and now I was sort of like, Oh, you know, really it affected me.

Ariana Brocious: Good climate news, good environmental news can be slow moving, can be highly technical, I think it can be easy for people to read the news and think that we're in a pretty dire situation. Um, how do you think about climate defeatists versus climate deniers?

Rebecca Solnit: I feel like there's concentric circles of climate understanding, and then I feel like I'm making a model of Dante's hell, but we'll set that aside. I think his ring sort of descended, mine might ascend. Maybe this is purgatory. But I feel like the denialists are just refusing the information, and I think a lot of it is because what the natural world is constantly telling us is everything is connected to everything else and we all have responsibility towards the whole, which is a very anti rugged individualist, anti free marketeer, um, libertarian thing. But climate defeatists who abound, They don't deny that climate is real. They often deny that solutions are real, that the movement is real, that coverage is real, that people caring is real. So they have their own amount of denial. There's a kind of depression where you just want to sit in the corner or curl up in fetal position or whatever, but these sort of evangelists of giving up, like the energized ones, I don't fully understand it. When you get to the organizers, the scientists, the journalists, the people who are really involved, they're scared, but they're not despondent. They know that this is the decisive decade, that we... The future is what we will make it in the present. There are parameters, of course. We can't make it like we never burned those trillions of tons of fossil fuel and put all that carbon dioxide in the upper atmosphere. But we have tremendous choices in this moment. And the difference between the best case scenario and the worst case scenario is profound. I wrote an essay called Despair is a Luxury because for most of us giving up, at some level we secretly know that we can give up and our lives will still be relatively comfortable and safe.

Ariana Brocious: It's easier to give up, don’t you think?

Rebecca Solnit: Yeah, and you, and so what you're really doing is you're giving up on behalf of people. You're saying, let those kids starve. Let the, let those, let that ice melt. Let those storms destroy the crops of those people in Central America. We who are relatively comfortable, safe, affluent, and therefore powerful, I think have no moral right to give up and we're giving up.

to let other people die first, other people lose first, other species lose first, I don't think it's ethical, and I think the facts say there's a lot worth fighting for now, and fighting for it is a really good way to live.

Ariana Brocious: So that strikes me as lacking empathy, lacking understanding

Rebecca Solnit: you you mean the giving up?

Ariana Brocious: That, that, that not comprehending the impact that your inaction might have. So how do we build more empathy, more understanding?

Rebecca Solnit: One thing that I found fascinating when I finally understood what most human rights and environmental movements do, first of all, is try and make the invisible visible. and so much climate work is just making visible what's happening with oceans, what's happening with the global south, what's happening with rainforests, what's happening with impacted communities but also making visible the movement, the solutions and the victories. And I think the left historically is really bad at celebrating victories and the climate movement has a hell of a lot more we need to do, but we've accomplished a lot.

Ariana Brocious: So how do we celebrate victories more? Because I think this comes back to the idea that environmental stories, you know, one editor told me once, they ooze, right? They just kind of like incremental things, they go bad slowly, they get better slowly. There's not as much drama. But there's been a lot of environmental or climate victories that are preventing harm. Rather than achieving a new solar plant or something. So how do we celebrate those?

Rebecca Solnit: There’s both. And, you know, well, I have a several page section I compiled of climate victories going back to the early 70s. And people, it feels like victories get forgotten overnight. A lot of victories look like nothing. The forest wasn't cut down, the toxic incinerator wasn't built in the inner city neighborhood, so the kids didn't get asthma, uh, um, the coal plants, the liquid natural gas export facility wasn't built, etc. So a lot of times if you're looking for victory, it literally looks like nothing, it's a thing that didn't happen. But a lot has happened and is happening. Bill McKibben pointed out the other day, we're implementing solar energy so fast. it's the equivalent of a. a large nuclear power plant opening every day.

One of the great victories climate people often hark back to is the Montreal Treaty to stop the ozone depleting gases, which was actually really successful. And then just in the last few years, there was a major milestone in the recovery of the ozone layer because we had this treaty. And treaties sometimes work. But, a lot of it is on the media, which is... It's part of my job and yours. but all of us are storytellers. one of the things that happens at a lot of climate events is people ask what can I do?

A lot of what you can do is be informed on climate, including the victories and the possibilities and bring them up in conversation and be equipped to counter defeatism, despair, because power also lies in the grassroots. It lies in good ideas, it lies in civil society, it doesn't just lie in elites, which is the story we're often told to make us give up.

Ariana Brocious: So I want to turn, this is actually a great segue, I'd like to ask you to read something, an excerpt from an essay you wrote in, following the 2016 presidential election called How to Survive a Disaster. And, uh, I'll ask you to read this and then we'll talk about it a little.

Rebecca Solnit: The ideal societies we hear of are mostly far away or long ago, or both. Situated in some primordial society before the fall, or a spiritual kingdom in a remote Himalayan vastness. The implication is that we here and now are far from capable of living such ideals. But what if paradise flashed up among us from time to time, at the worst of times? What if we glimpsed it in the jaws of hell? These flashes give us, as the long ago and far away do not, a glimpse of who else we ourselves may be and what else our society could become. The door to this era's potential paradises is in hell.

Ariana Brocious: I love that last line and this idea of finding paradise, of finding solace and comfort and community and togetherness in the worst of times. And, you write in that essay and I think in some other places about responses to disasters like Hurricane Katrina. So, how did you come to this idea that these times that can seem like the most dire can actually be really powerful and uplifting and community building?

Rebecca Solnit: San Francisco earthquakes taught me that. First, I lived through the 89 earthquake, as I'm sure a lot of you did, whose 34th anniversary was just a few days ago. And I was amazed to find that, like, all the things I'd been fretting about, simmering over, We're just completely erased like I was mad at somebody who was behaving badly. I never thought about him again and You know people all over the city came out and directed traffic because there was a complete blackout People just figured out what needed to be done and did it in North Beach For example, the power was out for three days to restaurants rather than let their foods like, set out barbecues and started feeding the neighbors. And fed the great anti nuclear peace marches, wa set up community kitchens and fed the first responders. who were working at the freeways, um, you know, uh, the fire department putting out the fires in the marina was only able to do that because, um, huge numbers of volunteers showed up to help them run those hoses from the ocean to, get some water, et cetera. The first responders in any disaster are your neighbors. And what happens is that by the time the news cameras get there, the professionals have often also gotten there. You'll get these exciting search and rescue teams who are wonderful. But if you've been pulled out of the rubble that first day, it's probably the neighbors, people are resilient, um, generous, empathic, creative, courageous –

Ariana Brocious: that people really come together and find like a truer sense of being in these situations, I think is one that is very hope filling when you think about what future... Most likely, uh, you know, even if we do accomplish what we're hoping in terms of keeping climate impacts lesser, we're still going to have them, we're going to continue to have them, and we're going to have to find that resilience.

Rebecca Solnit: In order to do what the climate requires of us, there's a lot of very practical, wonky stuff. You know, and very physical stuff. We need to change, um, You know, we need to electrify everything. We need to change how this, what the world runs on. But I also think that we need to change our imaginations, our values, our relationships. What's encouraging about how people respond to disaster is you see this deeper sense of who we are and what we really want, who we could be. And I feel like we have to be... We have to escape from consumerism, we have to escape from the kind of loneliness and isolation that Silicon Valley and a lot of other structures in our society have helped create. We have to feel that we can have an age of abundance, but abundance will be... In confidence in the future and the society we live in, confidence in our institutions and each other, a sense of belonging, um, a quality of life that will lie in our relationships to other human beings, other species, the natural world. And so I feel like that what disaster shows is that this is who we can be. It kind of shows a way forward, but we need to change the stories we tell about what a good life, a good society, and wellbeing look like as well.

Ariana Brocious: Rebecca Solnit is a writer, historian, and activist. Her most recent anthology is Not Too Late. Changing the climate story from despair to possibility. Thank you so much for joining us here on Climate One.

Rebecca Solnit: Thank you so much.

Ariana Brocious: And that’s our show. Thanks for listening. You can see what our team is reading by subscribing to our newsletter – sign up at climate one dot org.

Greg Dalton: Climate One is a production of the Commonwealth Club. Our team includes Brad Marshland, Jenny Park, Ariana Brocious, Austin Colón, Megan Biscieglia, and Ben Testani. Our theme music is by George Young. I’m Greg Dalton.