What More Can I Do?

Guests

Eliza Nemser

Jonathan Foley

Summary

As climate change impacts our lives more and more, many of us want to know: what can I do to make a difference? If the scale of the crisis feels overwhelming, there’s good news: what you do in your own life matters – a lot. It can be as simple as talking to your neighbor. And by engaging with our communities, we can do more – together.

The scientific consensus is that we have to quickly reduce carbon emissions – largely by moving away from burning fossil fuels – if we want to keep the Earth habitable for humans and other life. And one way to get there is to start with individual actions, as first steps on a ladder of continued sustained action.

There are many things we can all do to help drive systemic change while walking a bit more lightly on the earth. Many of these are well-known: buy less stuff, eat less meat, electrify your home and get off methane gas. But there are other actions we don’t always think of, such as where you do your banking, and getting involved in local decisions about roads, transit and housing.

Daily choices lead to habits, which can lead to larger trends and wide-scale change. Added up, those can have a real social and economic impact. Especially if they inspire people around you to do the same.

One resource that many of us overlook is the impact of our time. When it’s deployed in a strategic way, it can be a major climate lever. Eliza Nemser leads Climate Changemakers, a group that helps people become advocates and volunteers, to support civic action and engagement for climate policies.

“Anyone can reach out and schedule a constituent meeting and meet with policymakers and their staff. Most people don't, but anyone can. And surely if we're all using our own spheres of influence, our own networks, we have more proximity to power than we think,” she says.

There’s also a lot of power in living aligned with your values. Nemser says seeing the outcomes of your own civic engagement can help with climate despair and eco anxiety.

“You often hear action is the antidote to anxiety. I think self-efficacy and the type of volunteerism where you recognize your own agency is the antidote to apathy.”

Find more resources on how to be a climate-conscious citizen on our website. And remember:

“ You're not in this alone,” Nemser says. “A lot of us are going through this, and we can all be part of the solution together.”

This episode also features excerpts from Cory Booker, Anna Lappé, Frances Moore Lappé, Saul Griffith, Monique Figueiredo, Jonathan Chapman, Jennifer Anderson, Tanya Gulliver Garcia, Vernon Walker, Abrar Anwar, Slater Jewell-Kemker, Kyle Gracey and Alec Loorz.

Episode Highlights

04:30 – Eat less meat, and more plants

09:00 – Benefits of composting

11:00 – Electrify your life!

13:30 – Ride your bike (or bikeshare), carpool, use transit

14:30 – Consume less, and be satisfied with what you already have

16:00 – Bring a climate lens to your job

19:00 – Jon Foley on best and worst climate levers

29:30 – Time is the most important variable when addressing climate change

30:30 – Where you do your banking

35:45 – Participate in mutual aid

38:30 – Eliza Nemser on civic engagement and climate advocacy

50:00 – Advice from youth activists

What Can I Do?

Resources From This Episode (3)

Full Transcript

Note: Transcripts are generated using a combination of automated software and human transcribers and may contain errors. Please check the actual audio before quoting it.

Ariana Brocious: This is Climate One. As climate change impacts our lives more and more, many of us want to know: what can I do to make a difference?

Eliza Nemser: We're just people, we’re worried for a whole host of our own personal reasons. And that's why we're doing something.

Ariana Brocious: If the scale of the crisis feels overwhelming, there’s good news: what you do in your own life matters – a lot. It can be as simple as talking to your neighbor.

Jon Foley: Sometimes it's those neighborhood conversations about like, hey, this is actually going to make your life better. This is going to make your home more comfortable or save you money.

Ariana Brocious: And by engaging with our communities, we can do more – together.

Eliza Nemser: You're not in this alone. A lot of us are going through this, and we can all be part of the solution together. And then there's this added bonus of collective action.

Ariana Brocious: What More Can I Do? Up next on Climate One.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One, I’m Greg Dalton.

Ariana Brocious: And I’m Ariana Brocious.

Greg Dalton: You know, after having conversations about climate for so many years, there’s one question I get asked a lot – and that’s “what else can I do?”

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, me too! I hear this all the time from people I talk to, once I tell them what I do for a living. Actually, I get one question first, which is, “how screwed are we??” and THEN, “I recycle, I try to fly less… what else can I do? What really makes a difference?”

Greg Dalton: We need to drastically cut the emissions we’re putting into the atmosphere. We know what to do, but getting there isn’t simple or easy. The systemic forces are overwhelming for an individual.

Ariana Brocious: But there are many things we can all do to help drive systemic change while walking a bit more lightly on the earth. On the show today, we’re revisiting conversations with people who have helped us understand how to do those two things simultaneously – how we can reduce our personal impact and create change on a larger level. Think of this episode as your climate toolkit: full of a bunch of different tactics you can apply in your life, in your community, and beyond.

Greg Dalton: You likely already know some of the main ways you can reduce your personal emissions – buy less stuff, eat less meat, electrify your home and get off methane gas. But there are other methods we don’t always think of, such as where you do your banking. And getting involved in local decisions about roads, transit and housing. How our communities are built and run has a bigger impact than what kind of straw you use.

Ariana Brocious: I know it can feel like A LOT. So, we’re going to break this up into steps, starting with things we can do personally, on a daily basis, and then moving to larger forms of action. Partly because I think it can feel easier to do something small to get started. And also because as citizens of the Global North, we are responsible for MUCH higher emissions than most of the rest of the world. So what we do really matters.

Greg Dalton: Yeah. And even bigger actions, like replacing your gas car with an EV, can seem trivial when compared to global emissions. But more EVs on the road sends a social and economic signal. There’s real power in building cultural norms and support for policies beyond the direct emissions from your car.

Ariana Brocious: And we want to hear about your own climate journey, the steps you’ve taken, and what’s worked in your life.

Greg Dalton: You can share your actions and experiences by emailing me at greg at climate one dot org, and we may include them on a future show.

Ariana Brocious: Personal responsibility is super important, of course. But right off the bat this gets kinda tricky, because for decades the fossil fuel industry has been making average people feel like their actions are the main cause of the climate crisis.

[CLIP from BP’s “climate footprint ad”]

Remember BP’s “climate footprint” tv ad from a couple years ago? It tried to shift the focus away from big oil and focus the blame on individual consumers. That's a tactic polluting industries have been using for decades -- like that famous Crying Indian ad from the 1970s.

(AUDIO CLIP People start pollution. People can stop it)

In actual fact, the vast majority of emissions contributing to climate change belong to a handful of corporations and industries.

Greg Dalton: We want to be very clear: the scientific consensus is that we HAVE to quickly reduce carbon emissions – largely by moving away from burning fossil fuels – if we want to keep the Earth habitable for humans and other life. And one way to get there is to start with individual actions, as a first step on a ladder of continued sustained action.

Ariana Brocious: Right. Daily choices lead to habits, which can lead to larger trends and wide scale change. Consider, for example, cow’s milk. As we’ll hear about in a moment, the cattle industry contributes a ton of emissions. But in 2022 Gen Z bought 20 percent less milk than the national average. As a generation, they’re just not a fan of milk. And think about how many coffee shops now carry oat milk, which is much kinder to the environment.

Greg Dalton: Right, lots of battles about what milk is. Small change can snowball into activism or policy or entrepreneurship, or even change the market itself. There’s also a lot of power in living aligned with your values. It can help a lot with climate despair and eco anxiety, which we’ll talk about later in the show.

Ariana Brocious: Okay, so first up in “What Can I Do”.... eat less meat! I know, I know, this is probably the first thing you thought of. But wow, it is significant. According to the EPA, agriculture accounts for about 10 percent of global greenhouse gasses, and about half of that is from livestock. Plus, it takes a ton of land and water to raise meat and the feed we give to cattle, in particular. And both dairy and beef cows contribute a lot of methane to the atmosphere. And methane is, of course, a super potent greenhouse gas.

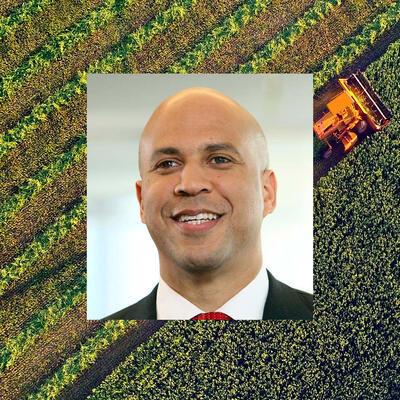

Greg Dalton: Right 500 gallons of water to grow a hamburger, and it gets worse: growing crops to feed cows worsens deforestation in the Amazon. So the impacts of consuming beef and dairy are vast. Now we’re not saying you have to become vegan – though some people choose to do that: like New Jersey Senator Cory Booker. He’s pushing for a number of bills that would reform various aspects of U.S. industrial agriculture.

Cory Booker: We are a nation right now that is using practices, forget your diet for a second, that are unsustainable. And as the entire planet earth is moving more towards the standard American diet, as the globe is moving more towards our diet. We will probably need about four planet Earths just to have the land necessary to feed the exploding demand for pork, chicken and beef.

Greg Dalton: And Cory Booker isn’t just driven by the sustainability or carbon emissions side of it, it’s also how these systems impact the welfare of animals and human beings. He told me about visiting confined animal feeding operations, or CAFOs, in Duplin County, North Carolina.

Cory Booker: These contract farmers who have miserable lives because they’re a few steps short of sharecroppers. But these big multinational pork corporations who, three or four of them control the whole market dictate to the contract farmers how they have to raise things, big warehouses of pigs, all the feces going through these grates into massive lagoons and then they’re sprayed onto fields in low income communities. And so, you walk through these communities, communities of African-Americans who have been on that land since slave times, since slavery was around. And now the value of their land is going to the floor. They can’t open their windows. They can’t put their clothing on the lines. They have respiratory diseases, clusters of disease there spiked and they said how can we have this happen? How could Americans eat their bacon and not understand how we’re suffering?

Ariana Brocious: Food and food systems are areas where we can make changes and feel the impacts pretty directly. We talked about this with Anna Lappé. She’s Executive Director of the Global Alliance for the Future of Food. She explained that solutions that reduce the damage agriculture and livestock have on the planet – things like regenerative grazing, planting trees, improving soil health, reduced use of fertilizers – those can ALSO build climate resilience.

Anna Lappé: Those solutions are going to make farms more resilient to climate shocks, that it's going to push farmers and support farmers and moving toward growing a more diverse set of crops, which is good for our health, as well as resiliency, and that was so exciting to realize that, yes, we can think of food systems as part of the casualty of this crisis, right, that farmers are on the front lines, that they're a huge cause of the crisis, but also they really are farmers and folks working on food systems, a key part of our solutions to get us, get us out of this climate catastrophe.

Greg Dalton: Anna learned a lot about the connections between agriculture and climate from her mother, Frances Moore Lappé, author of the hugely influential cookbook “Diet for a Small Planet,” which was published more than 50 years ago. Frances Moore Lappé says change can happen through legislation and policy but also through our own actions. Just cutting back on the animal products you consume can make a big difference, if enough of us do so.

Frances Moore Lappé: Food has special power because we can't choose, we can't buy a new solar panel every day, you know, but we can choose what we put into our mouths every day and it ties us, we know, to each other, to the earth, to the climate. And so I think it has a sense of, as we align those daily choices with the world that we want, we feel more powerful.

Greg Dalton: Plus there’s well-backed science that eating more plants and less meat is far better for your health. So go ahead and lean into a plant-powered diet. Maybe try eating meat only a couple times a week, rather than every day.

Ariana Brocious: And compost, if you can, because food waste rotting in landfills emits a lot of methane.

Monique Figueiredo: Composting is one of the most impactful things you can do for climate change.

Ariana Brocious: This is Monique Figueiredo, the founder and CEO of Compostable LA. It’s a food scrap pickup service. She says composting benefits the climate in several ways:

Monique Figueiredo: One, it takes organics out of a landfill, and organics in a landfill become methane. They kind of slowly mummify while rotting because the conditions in a landfill are so tightly packed that they create these anaerobic conditions, these conditions without oxygen. And when that happens, food scraps can't decompose properly, and so they release methane, which is way worse than carbon dioxide in the first 20 years of its life.

And then the other part of composting, which I really think is the, the powerful part of composting, is the soil creation aspect. Because when you create healthy soil, and when healthy soil has a relationship with plants, you get this entire other sphere of benefits. You have stormwater filtration. It's holding water to help with flooding and drought. It's creating more nutrient dense food because there's more nutrients in the soil itself from the compost. So, you know, it's healthy humans. It's healthy air because it's pulling carbon dioxide out of the air and storing it in the ground where it's good for the plant. So, it gets deeper and deeper and deeper the further you start digging into the world of composting.

Ariana Brocious: So whether you do it under your sink, in your backyard, or through a service, try to compost your food waste. Next up on our tools for change: electrify your life!

Ariana Brocious: Saul Griffith is the author of “Electrify: An Optimist’s Playbook for our Clean Energy Future.” He says when we electrify everything – that means our homes, our cars, our power utilities and major industries, we'll only need about half the energy we currently use.

Saul Griffith: Fundamentally, electric machines don't generate the waste heat internal combustion engines do. An electric car uses about one third of the energy to go the same distance as a gasoline car, provided that you provide the electricity from a clean source like wind or solar or hydroelectricity. And then, what's underappreciated in the American energy economy today, and in fact, in all, all the countries of the world is that we generate our electricity thermo electrically. What that means is we heat water to make steam, spin a turbine to turn a generator to make electricity. But a huge amount of that energy is wasted as heat. Sometimes half in natural gas, sometimes two thirds of the energy is wasted as heat if you're doing it with coal. So if we electrify all of the demand side machines, that means the things that you and I recognize because they're in our garage or they're in our kitchen or they're in our basement, and then we provide them all with electricity that's produced with sunshine and wind, we actually probably only need 40%, definitely less than half of the energy we think we need today.

Ariana Brocious: Though he does appreciate how much it will take to get us there, Griffith makes a strong case for electrification. And he says the benefits are vast.

Saul Griffith: The health of our communities and the smog in our cities caused by all of the oil we're burning in our cars is another thing that will lead to greater respiratory health. It will have huge health benefits beyond that as well, and our skies will become clearer. The air around us will become cleaner. The waterways will become cleaner. On top of that, we can now see that energy is very likely to actually get cheaper, not more expensive. Wind and solar really are just so cheap now and batteries are about to be so cheap and electric vehicles are about to be so cheap. You know, we'll see thousands of dollars of savings in every household every year.

Greg Dalton: And this is one climate strategy where you actually have money to help you do it, too, thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act.

Ariana Brocious: Right. Depending on your income level, there are direct subsidies and tax credits for doing things like switching your furnace from gas to a heat pump, putting in an electric water heater, buying an electric car, and so on. The folks at Rewiring America have a very helpful guide to these credits and rebates. You can find a link in the show notes or on our website.

Greg Dalton: And while I LOVE my electric vehicle, another tool for addressing climate disruption is simply to drive less. Ride your bike, take public transit, carpool, combine your errands into one trip. Less miles traveled by combustion engines means better air quality and public health, in addition to reduced climate-harming emissions.

Ariana Brocious: I recently got a very cool electric cargo bike to take my kids to school. And I’ll be honest here – many mornings, especially in winter, I don’t want to bike. I want to sit in the comfort of my warm car. But I make myself do it and as soon as I get on the bike, I feel so happy. I get to travel the neighborhood streets instead of the major traffic arteries. I see neighbors walking their dogs, I feel the sun and wind and my body is in motion. It’s a really nice start to the day.

Greg Dalton: I love riding to work, you’re closer to the community. When I bike or walk, it’s good for my health, it’s good for my mood. And you don’t necessarily need to buy a bike – a lot of cities have bike shares.

Ariana Brocious: Another strategy for reducing your impact is simply to consume less. Take stock of what you already have and keep using it rather than replacing it. A great example of that is what’s in your closet.

Jonathan Chapman: It's true to say that the most sustainable clothing there is in, in many respects, the clothing that you already have. A lot of what we could probably do better is just learn to, I suppose be satisfied with what we have.

Ariana Brocious: Jonathan Chapman is a design professor at Carnegie Mellon University who studies our relationship with material things. Here’s his advice on being a more climate conscious consumer:

Jonathan Chapman: Choose something that's going to be technically durable. That's going to last. That when you wash it, it isn't destroyed after the first wash, ideally choose something that doesn't require ironing a whole lot. So there's a lot you can do at the point of purchase, but I also think there's something about once you own the thing and it goes into your wardrobe or in a drawer or wherever it goes. I think it's about what happens after that, that really matters in terms of the way you live with it, the way you keep it, the places you take it and the way you pay attention to the role that it plays in your life. Because I think if you allow it into your life and spend time with it in that way. You're more likely to form meaningful stories with the thing.

[MUX]

Ariana Brocious: So these are all things you can do as an individual, and as a consumer – changes to your personal habits. But the next step on this climate action ladder happens in your professional life: you can help make change by bringing a climate focus to your job. We recently did an episode on Six People Who’ve Changed Their Jobs for Climate.

Greg Dalton: One of them is Jennifer Anderson, who spent 20 years as a petroleum geologist for the oil and gas industry. At one point she went to a city council meeting and heard local people testify about the health and environmental harm caused by her industry. She realized she wanted a change. So she left her job, and got some advice from a mentor:

Jennifer Anderson: And she was very frank. Jennifer, there are no do overs, is what her guidance to me was. When we're talking about the climate emergency, there's no time to reinvent yourself. Whatever you have in your background, you need to use it.

Don't run away from it. Don't, you know, like, uh, think of Your story's your story. Embrace it. Yeah, own it and use it. And it was sort of a lightbulb moment. Like, wow. I had wanted to get so far away from oil and gas that I thought I needed to reinvent myself. And, uh, just based on what she said, it was, like I said, kind of a light bulb moment and helped me see things a little differently.

Greg Dalton: Anderson ended up studying climate science and transitioning her skills into carbon removal. She said it was hard, but very much worth it. Now she works at Charm Industrial, where she uses her skills to put carbon back in the ground.

Ariana Brocious: But you don’t need to overhaul your entire life to have an impact. Think about the ways your job, or the company or organization you work at right now, impacts the atmosphere and environment. Can you encourage your workplace to adopt more climate-friendly behaviors or policies? Can you get your company to provide low-carbon mutual funds as part of your 401k plan?

Greg Dalton: Every job can be a climate job!

Ariana Brocious: Okay. So far we’ve talked about a lot of the obvious, though perhaps not always easy, ways you can make changes in your own life to be a climate conscious citizen.

Greg Dalton: But what about the less obvious ones? Coming up, how to evaluate which climate tools will have the biggest potential impact:

Jon Foley: Now is better than new. And time always is more important than tech because time is the most important variable when it comes to solving climate change.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton.

Ariana Brocious: I’m Ariana Brocious. And today is all about answering a question we get all the time – what can each of us do to address the climate crisis and have real impact?

Greg Dalton: We’ve already talked about many of the choices you can make in your own life: buy less stuff, eat less meat, switch your gas car for an EV, compost… Added up, those can have a real social and economic impact. Especially if they inspire people around you to do the same.

Ariana Brocious: Someone who’s done a lot of thinking about that is Jon Foley. He’s the executive director of Project Drawdown, which he describes as the “consumer reports” for climate solutions:

Jon Foley: We do the research that very few others do looking at the efficacy and cost and scalability of solutions around the world and share that with investors, governments, communities, and philanthropists so we can put the best solutions in motion as quickly as possible.

Ariana Brocious: I wanted to talk with Foley because I’m fascinated by Project Drawdown’s Solutions Library– it’s about a hundred climate solutions they’ve carefully vetted and explained. I asked him what he thinks people underestimate or misunderstand about their own role in addressing the climate crisis.

Jon Foley: I think there's been a false debate out there for a while, that it is a choice, some kind of binary choice between big systems change of our politics and how business works or our individual actions in our community and at home and in our daily lives. What I think is a kind of a confusion point there is like that we have to choose one or the other, or that you can only do one. That's not true. They reinforce each other. I think a lot of people are surprised that your personal actions do matter a lot, not just in terms of the material impact of how much carbon was actually prevented from going in the atmosphere, but also that it speaks volumes to other people culturally, economically, politically, socially, in so many ways. Every day that we show that we're doing a climate solution by maybe eating differently, by retrofitting our house or changing our cars or how we get around, we're sending signals to the world around us every single day. We're all kind of micro influencers. Why would we want to give that up compared to voting, which we do once every four years and may or may not have any impact at all. But this is like voting with your life every single day. So I emphatically believe that, you know, acting on our personal lives is a powerful way to change the larger system as well as voting and watching where our money goes. They'll work together and that surprises people.

Ariana: I think it's an exciting and inspiring way to think about it because it does give you the feeling that your actions matter, which really fights that sense of apathy or nihilism that can often come with talking about climate. And, you know, I have an example that I'd like to share of just the small ways this can happen. I have a neighbor I've started to get to know, our kids go to the same school, and I started talking about my stove. I got an induction stove about a year ago, and we were just talking conversationally, and she was asking more for safety about her son who really likes to cook, and being worried about an open flame. So I described the stove I had gotten and how much I like it. She asked me for the brand name and I provided it. And then I saw her a week later and she said, Hey, I'm getting my new stove tomorrow. And she was so excited. And you know, that's just like one small reflection. I'm sure there were other factors influencing her, but it's nice to think that, um, as you said, we can model behaviors. We can sort of help others think differently about these solutions too.

Jon Foley: Well, exactly. I used to live in San Francisco, and now I live in rural Minnesota. A little bit of an adjustment. And I live in a county that's majority Republican. If I went around throwing soup at people's artwork, or if I started telling people how they should vote for this politician versus that politician, it probably wouldn't go very far. But when I got my new electric car, all of my neighbors all wanted to drive it and kick it around. They're like, this is amazing. This is really fun. This is a great car. And a whole bunch of them are thinking about as their next vehicle, getting an electric vehicle. That's a change that wouldn't be possible if we only pulled the politics lever or the protest lever. That doesn't work always. And sometimes it's those neighborhood conversations about like, hey, this is actually going to make your life better. This is going to make your home more comfortable or save you money or create jobs. That's the weird thing about climate solutions to me is like, why do we lean with the climate foot in every situation or a political foot forward and our dance with other people? How about we lean in with another foot, which is talking about, hey, this is going to make your house more comfortable or more valuable or safer or save you money or something that everybody agrees with. And so, this kind of so-called polarization we think is real in America about we can't talk about climate with half the country, that's not true at all. As you found out, as I found out, when you talk about climate solutions in real terms as neighbors, not as politicians or activists you get a lot further and it reminds me like Katharine Hayhoe one of our, somebody we all mutually admire. She often says the best thing we can do about climate change is talk about it. And that's what's really nice about personal actions is they’re relatable and they also give you a reason to get involved with climate solutions even if you don't care at all about climate change because climate solutions by and large save you money and they make your life better.

Ariana: Yeah, I know people who are really interested in solar and battery storage because they want to be off grid for self resiliency does nothing to do with actually this power source so much. So I want to take one step back and we've been talking about personal actions, which is really valuable. And we'll come back to that. But when you look through the project drawdown library at kind of the established climate science that we have today, what are the biggest and most effective climate levers that we have we can, we can work on right now?

Jon Foley: Well, what's really exciting is that the world is finally really paying attention to climate solutions. We're starting to put some real money behind it now. And some very exciting things are happening. So, for example, in the electricity column, the big part of the problem, but not the only part we see renewables taking off solar, wind and storage are getting cheaper, better, faster than ever before. That's awesome. I'm also excited what's happening in buildings with heat pumps. Because heat pumps are now the killer of furnaces and boilers and old air conditioners. We now have the killer app. The thing that makes everything else obsolete and still better. It's cheaper, more efficient, more convenient, more pleasant than what we used to use before. In transportation, the electric vehicle is the killer app.That's better and will be cheaper and better and more effective than the fossil fuel vehicle. And it costs me like, you know, five bucks to quote, fill my tank in my electric car compared to $30 at the gas pump. When climate solutions win is when they beat the others in the marketplace and finally those technologies are being unleashed, but I also think we need to pay attention to other things that aren't just technological miracles sitting around, taking over the world. We have to think also about things like methane leaks in pipelines. Methane's a really important part of climate change because methane warms the atmosphere a lot. And it warms it really fast.

Ariana: Right.

Jon Foley: So plugging the methane leaks in natural gas, abandoned wells, abandoned coal mines, pipelines, refineries, all that is crucial. Also fixing methane in agriculture, which is going to be harder, is crucial. Deforestation is another crucial issue. A lot of people are stunned to realize that deforestation emits more greenhouse gasses, more CO2, to the atmosphere than the entire United States economy.

Ariana: That's staggering. And I just want to jump in and say, you know, people think of deforestation, it might feel disconnected or far away, but a lot of that deforestation is happening to raise cows, to make burgers or to grow soybeans in Brazil that are also often going to feed cows, right?So what you eat also can have an influence there.

Jon Foley: Yeah. Most of the deforestation in the world is caused by agriculture, so yeah, what we eat matters a lot and it's driving most of the deforestation, which is a huge climate problem. But it's also the number one biodiversity problem, this clearing of habitats as well as vast stores of carbon is a big problem for the planet in the climate, biodiversity and human columns, because this is also where a lot of diseases that affect humanity later come from is from animals living in rainforests. So keeping them intact, keeping them wild, keeping them full of biodiversity and full of carbon would actually be really good for us in the long run.

Ariana: Now let's just briefly touch on the ones that maybe get a lot of attention, but are actually not that effective. The false or sort of ineffective climate solutions that are talked about right now.

Jon Foley: Well. One of the things that's really important about climate change and why some solutions aren't going to be a big player, is all about time. Because climate change is a cumulative problem facing the planet. It doesn't happen in one year. It happens over many decades. So the temperatures we're seeing around the world today, shattering records, causing extreme weather events, and all these disturbances we're seeing, is caused not by just this year's emissions, it's caused by the last, you know, 200 year’s emissions building up in the atmosphere. While climate solutions work the same way out in the future, it's not about what a climate solution will do in the year 2050. It's about what it does every day from now until 2050 and beyond. So, we talk about the time value of money. Like if you want to be retiring when you're 65 or 70, you better start saving now and accumulate money over time and build up a big impact when you retire, right? Same thing with climate solutions. We better start now and accumulate impact until mid century when we hit net zero and stop climate change, right? That means there's a time value of carbon just like a time value of money. Every year we wait, waiting for a technological breakthrough, waiting for the silver bullet, the shiny tech object that will save us all, we lose a year of effectiveness. In fact, every year we wait for a climate solution, you can discount its effectiveness on stopping climate change by about 7%.

Ariana: Wow.

Jon Foley: Every year compounding means you wait 10 years. You lose half the effectiveness in terms of steering the world towards net zero in time. So when people like Bill Gates and others talk about fusion, I just laugh. I mean, fusion's always 20 years away, and always will be. That's not a climate solution. Same thing with advanced nuclear, carbon capture, hydrogen, these big clunky projects that always seem to run over budget and off schedule and consume vast amounts of government resources. These are not only not solutions, they're worse than that because they're a distraction from actually implementing solutions that do work today. Especially carbon capture. So we often have a saying at Drawdown, which is, “now is better than new. And time always is more important than tech.” Because time is the most important variable when it comes to solving climate change.

Ariana: So in other words, we need to take the tools we already have and sort of employ them to the max instead of looking for some of these other solutions that might come into play 20 years from now, but aren't going to significantly bend that curve.

Jon Foley: Absolutely. To address climate change, we need to bend the curve now and keep bending it. That doesn't mean new technologies can't help out in the future too. Let's fold them in as we get them. Great. And the good news is we actually do have. Almost all the solutions we need to stop climate change right now. Some of them are a little bit more expensive than we might like. Some of them aren't as convenient as we might like. But most of them are actually cheaper than fossil fuels, and better, and healthier, and give us more security. We just need to get moving.

Ariana: Well great. That's good news. So let's return now to the role of the individual. This episode is about what more can I do? So there are things people don't think about so much. So could you give us a couple of those?

Jon: Sure. So examples of climate solutions we might not think about. First, I guess I would mention, we just did a report on this, is banking. Like, where do we park our money? The median household in the United States has about $8,000 in the bank between checking and savings accounts. That $8,000 is being used by a commercial bank to lend it to somebody else while you are not using it. And that might include a fossil fuel company to build, you know, a well or a pipeline or some new infrastructure that's going to lock in fossil fuels. And so it turns out that, you know, the average family in America, without us even realizing it, is powering up industries that maybe we don't really like that much. So maybe you could look at alternative banks. There are some that actually pledge that they do not loan money to fossil fuels and you have a carbon free banking alternative. So those are some interesting ideas. Also, our 401ks and retirement plans, if you're lucky to have one of those at work, maybe see if any of those options you have for investing a retirement account, like a 401k, maybe they have green alternatives. And even, even just talking to your investment professionals and your bank managers about this issue, even if you don't change, at least gets them thinking about it too. And believe it or not, the more we ask about this, the more willing they're going to be to consider these options in the future. So I think that's a powerful lever we may not think we have. It's not just the ultra wealthy that can influence finance in the world. It's all of us in our little, you know, our own personal savings accounts and our retirement accounts. We collectively have a lot of power there too.

Ariana: And there are lots of resources on the Project Drawdown website, where people can find more information and they can also find these co-benefits that we talked a little bit about some of the ways that making these changes can improve your life in ways beyond the emissions themselves. Jon Foley is Executive Director of Project Drawdown. Thank you so much for joining us on Climate One.

Jon: Thank you for having me.

Greg Dalton: On our show, we like to talk about solutions on the systems level. In order to make change at the speed and scale scientists say is necessary to avoid the worst climate catastrophes, we need to be pulling big levers. And really, a lot of this comes down to power.

Ariana Brocious: And money. I’m glad Jon Foley mentioned money, because in many cases, money is power.

Greg Dalton: Right. But it’s not the only kind of power. As citizens can access power by tapping into another valuable resource – our relationships.

Eliza Nemser: And surely if we're all using our own spheres of influence, our own networks, we have more proximity to power than we think.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

[short music post]

Ariana: Please help us get people talking more about climate by sending this episode to a friend. You can also help by giving this podcast a rating or review – it helps other people find the show.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton.

Ariana Brocious: And I’m Ariana Brocious.

Greg Dalton: We've been talking about what more we can do as individuals to meaningfully address climate change. That’s the point of this episode. But I have to say, I often feel ambivalent about how much impact individuals can really have. The scale of the crisis is so big that nothing I do ever feels like enough. And there’s a growing group of people saying we need more radical, systemic change. It makes me think back to an interview we did with a former youth activist named Abrar Anwar. Here’s how he thinks about individual action:

Abrar Anwar: My advice would be to be a little more radical than we have been. Try and shake up the system. Governments don't like disruption. Shut down the road in front of your parliament, organize marches, but not just that. Get yourself into positions of power. Aim for places where you can stand toe to toe with lobbyists, with policymakers, with people who are influencing big oil, big energy. Get yourself in a position to be heard and making sure once you're in that position you don't back down and you don't change your opinions based on the pressure you will be feeling from your peers at the time.

Greg Dalton: What I hear Anwar saying is that we need to compel entire governments, and entire industries, to take big action in order to make a real dent in the problem. That’s where we need to focus our energy.

Ariana Brocious: I get that. But it’s not either/or, right? We’re all at different places on this ladder, we need people who are protesting AND people who are composting. We need all of it. That’s what we’re talking about today: the ways you can address the climate crisis through your actions. And how those individual choices can connect to produce a greater impact.

Greg Dalton: Right, do what you can where you are with what you can. We heard from Jon Foley about the false binary between individual and systemic action. We all need to start somewhere. Then take it one step further.

Ariana Brocious: Right and that’s what we’re going to talk about now: turning individual action to community action. And one of the most effective ways to do that on the local level is something called “mutual aid.”

Tanya Gulliver Garcia: I think the most important principle is just the idea that everybody has something to offer and everybody has needs.

Ariana Brocious: Tanya Gulliver Garcia, with the Center for Disaster Philanthropy explains what “mutual aid” looks like in action.

Tanya Gulliver Garcia: I think a lot of funding generally, but especially in disasters, is what we call white saviourism, where somebody who's wealthier, whether it's the global north to the global south, whether it's individual, says, well, I'm going to help these poor people. And instead, mutual aid is about saying, no, everybody has those skills and assets. We just need to bring that out. So I would start with that point and then take a look around and see what's already happening in the community. I guarantee you that in bigger cities, there's something already happening. There's already organized mutual aid groups in smaller communities. Get a few people together, talk to your local faith communities, find out what their needs are and start small. You know, talk to the local shelters who are providing services, the, the Ys, and see, you know, what's needed. Maybe adopt a school and, and start working with a school and have conversations because kids have assets too. There's lots of things that young people and youth could provide to a community as a whole and then receive other things in return.

Ariana Brocious: I love this idea of everyone having needs and everyone being able to help. And in a similar vein, we know that building connections in your community helps build climate resilience and can lead to local climate action. Here’s Reverend Vernon Walker, Climate Justice Program Director at Clean Water Action, who spent years doing that work in Boston.

Rev. Walker: Neighbors that are socially connected are less likely to die from extreme heat. Neighbors that are socially isolated are more likely to perish because of extreme weather events. And we know that climate change will bring more extreme heat events, more floods, and more hurricanes, etc. So let's build up the social connections and let's work with existing community organizations that have the community trust and that essentially are community anchoring institutions, such as faith communities and libraries and community centers, etc.

Ariana Brocious: So talk to people at school drop-off or your local coffee shop! Join your neighborhood association. Host a block party. Most of all, get to know your neighbors. Because in the case of a severe weather disaster, you’ll be relying on each other.

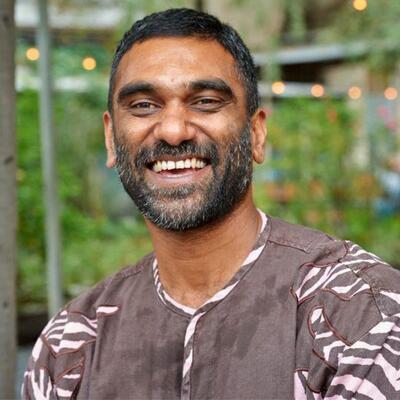

Greg Dalton: Another resource that many of us overlook is the impact of our TIME. And when it’s deployed in a strategic way, it can be a major climate lever. Eliza Nemser leads Climate Changemakers, a group that helps people become advocates and volunteers, to support civic action and engagement for climate policies.

Eliza Nemser: I knew very well we're at a stage where we need transformative systemic changes and progress hinges on our policymakers and their willingness and commitment to lead on climate.

Greg Dalton: After years as a professional geoscientist, she found herself advising oil and gas companies on earthquake hazards related to their operations. And then the climate threat hit closer to home. Nemser lives in California and she watched wildfires threaten the area near her. That's when she decided to pivot from science to advocacy.

Eliza Nemser: I started looking for my climate job. I started looking for grassroots volunteer opportunities and I signed up with a ton of organizations. My inbox was flooded with take action buttons and I would click and then I would feel the sense of disappointment, like I was asked to sign a petition and then pitch in $10. I also learned about grasstops advocacy, people meeting with decision makers and their staff, writing op-eds, that kind of thing. It's more time intensive, but very effective. And mostly left to the professional environmental advocates and business leaders and donors. So I became kind of fixated on how do we broaden participation in those strategies, like how do we democratize that.

Greg Dalton: And so just if I could jump in there, grass tops and grass roots. What's the difference between grass tops and grass roots?

Eliza Nemser: It has to do with kind of proximity to power and the strategies themselves. And frankly, sure, business leaders and people for whom it's their day job, and donors have more proximity to power inherently, but we all can gain proximity to power. Anyone can reach out and schedule a constituent meeting and meet with policymakers and their staff. Most people don't, but anyone can. And surely if we're all using, you know, our own spheres of influence, our own networks, we have more proximity to power than we think. So yes, there's very much ways to engage as a volunteer. I think it also has to do with how time intensive the strategies are, right? So again, these are taking the time to write letters to the editor, taking the time to have these meetings, taking the time to, to reach out in a personal way.

Greg Dalton: And I think that's key to the time intensity. A lot of volunteerism is sort of, you know, the annual beach cleanup or Earth Day. So talk about the time dimension here in terms of, is effective advocacy like weekly, monthly, or is it something I can check the box and feel good about and move on and kind of a contained period of time?

Eliza Nemser: I think both. It can definitely and needs to be time bound, right? We're talking about volunteerism. It also needs to be sustained and kind of habitual. So the best use of volunteer time creates meaningful impact and has tangible outcomes and fills us with a sense of purpose and reminds us of our agency, right? Planting trees, beach cleanup, it's great, but how can we as individuals create systemic change by working to shift priorities and influence policy at every level of government and every decision making table? We can help with that as volunteers. That's what advocacy is. To do it effectively, it is more time intensive, but it doesn't have to be your day job, right? It can be time bound. So Climate Change Makers is a volunteer advocacy program, and we focus on meaningful civic engagement. So we equip our volunteers. nationwide to drive systems level change by advocating, influencing policies at all levels of government. And you know, people can plug in as seasoned advocates or as first time advocates and, you know, go to, go from what we call zero to hero. I mean, we see it all the time. and oftentimes when you send a personalized outreach, you get a personal response back, and then you learn that your outreach was not only well received, it landed and it was acted upon and making a difference. And that really helps you realize your own agency and inspires you to do more.

Greg Dalton: Right, and your focus with Climate Changemakers is people have kids and jobs and full lives. So tell us how that process works through Naomi.

Eliza Nemser: We have these Hour of Action events. The idea is that Effective advocacy takes a little bit of time, carve out an hour. Naomi, at her first hour of action, scheduled a constituent meeting. She was just ready to go. After a successful constituent meeting, she was really fired up. She subsequently wrote a letter to the editor. It got published. She wrote her next letter to the editor, also got published, really felt emboldened. She was asked to join a climate advisory board and then started leading hours of action. And then, you know, after a year of doing this, she realized she had done like 70 some odd hours of action. So she created this infographic detailing. all of the impact she had made and shared it out around our community in Slack, inspiring other people. I'll give you another example. Tony in Missouri, his outreach on an Hour of Action, kind of using our playbooks, prompted the Missouri Department of Natural Resources to consider applying for Solar for All funding. This is happening around the country. Adam and Nicole in Kansas City and in Denver reached out to their city councils, prompted them to disseminate information about home electrification rebates to their constituents.

Greg Dalton: That's a big one, because the home electrification journey is complicated. because every home is different. I can see the power of that and sharing your experience with others. You mentioned government funding. There's a lot of money available coming through the Inflation Reduction Act for home rebates and for communities, et cetera. But it takes resources and knowledge to get at that government funding. Is that something that volunteers can help cities and communities do?

Eliza Nemser: That's definitely something that volunteers can help do. And volunteers can kind of act as connective tissue, right? And a lot of the outreach we've done this year as a community is very much along those lines. Is letting our counties know that they can apply for federal funding like there's direct pay in place now to help them electrify municipal fleets and we have volunteers reaching out and their counties weren't aware of that funding, right? So, that is definitely something that can be decentralized and volunteers can pitch in having never done this before and be effective advocates in their communities to help get this federal funding allocated faster. Equitably. I mean, we really need a lot of people. More hands on deck.

Greg Dalton: I really like what you said about individuals leading to systems level change. Are there other examples of how one person can have a systems level impact? Cause that's, it seems so, so daunting.

Eliza Nemser: It does. But, I mean, that's what advocacy is. I mean, I, I think, yeah, I have examples all over the place. Sigrid in Arizona reached out to her school district, prompted them to apply for EPA's Clean School Bus program.

Greg Dalton: Cool. Tangible. Cause school buses are dirty. Yeah.

Eliza Nemser: Totally tangible. And how do you think that made Sigrid feel? I mean, that you do something like, wow, look at, look at what I did in my hour as a volunteer. I helped make that happen. I mean, that's incredibly exciting.

Greg Dalton: And that's the, the feeling is something I wanted to ask you about because, you know, I, you know, once of every couple months deliver food for the food bank in San Francisco and I feel good handing a bag of groceries to a senior person. To be honest, I don't often think about climate volunteerism as, as something that's gonna make me feel good 'cause climate is often a scary, dark topic, and I wonder how you think about that as someone who is involved so actively in climate volunteerism? Is it a downer or can it make people feel good?

Eliza Nemser: I mean, I literally, we had a volunteer, Becca, report after an hour of action: This is like Tylenol for my climate anxiety. She said that. I think, you know, you often hear action is the antidote to anxiety. I think self efficacy and the type of volunteerism where you recognize your own agency is the antidote to apathy. So I think it does both. And it is very overwhelming, but when you do this kind of work in a community of people, it's really fortifying and actually, dare I say, fun.

Greg Dalton: And so what are some tips for someone who says, Okay, I have a few hours. I want to do something on climate. Not sure where to look or where to plug in. And maybe I don't feel like an activist who wants to march in a street. Where can I find my place?

Eliza Nemser: The first one is commit. You know, it's time to grab an oar and row. We all need to be rowing in the same direction and be real with yourself about the time commitment that you can make. I mean, will you volunteer an hour a week to push your school board to procure electric school buses and urge your county to electrify municipal fleets to, you know, to let your state legislator know that you're counting on them for climate leadership. So be honest about how much time you have to commit and then find a group. There's lots of climate organizations. Once you find a group, carve out the time, schedule it, and plan to make it a habit, because effective advocacy takes time, and we need sustained engagement. And then my other advice is to be courageous. You know, it takes you out of your comfort zone and be ready to level up and and do more and grow into your leadership. We need people who are helping to normalize civic participation. So setting a very visible example and talking about why you advocate, what moves you, what are you trying to protect? So I think the main thing is to show up.

Greg Dalton: Right. And also, you touched on find a group, which means it's kind of relationship based. I think a lot of people often think about climate like they think about impact and what and less about who they'll be doing it with. So talk about the social component of lasting and meaningful climate change.

Eliza Nemser: Yes, it’s pretty hard to stay motivated to do something over and over without a community to support you. I mean, the community component is huge. It's hugely important because, yeah, without that, you're going to fizzle out. But when you realize you're not in this alone. A lot of us are going through this, and we can all be part of the solution together. And then there's this added bonus of collective action. You have an outsized impact, right? We're greater than the sum of our parts, kind of thing. But it's, it's very important to feel that you're part of a community, which is why it makes sense to explore different groups and feel, find your action home,

Eliza Nemser: Frankly, we need more leadership on climate. We need community leaders. We need our elected officials leading. And so learning how to be an effective advocate is your, that's your path. That's your path to being a climate leader.

Greg Dalton: I guess we can all be a leader in some way, both in our homes and our lives. And then some people will go into the, you know, the public or civic square public sphere. Eliza, thanks so much for sharing your examples of people going from zero to hero.

Eliza Nemser: Thanks for having me, Greg.

[music]

Ariana Brocious: This hour, we’ve been talking about all sorts of things you can do to address climate in your personal life and broader community.

Greg Dalton: Addressing climate change is a long fight, one that will extend much longer than our own lives… and I want to acknowledge that it can feel hard. So we want to close today’s show with some words from a few youth climate activists about what motivates them to stay in the struggle:

Kyle Gracey: My biggest advice is to build community. We are not going to solve any of these problems by ourselves. These are complex, interconnected challenges and we need an entire society of people to do that effectively. It can be done. People have changed the world before and young people have changed the world before and they can do it again.

Slater Jewell-Kemker: You are going to feel depressed, you are going to feel overwhelmed, and it's okay to take a step back and to heal because you won't be able to continue this work if you just keep pushing on.

Alec Loorz: Trust your authority as a young person who will be impacted by this crisis. And remember that it's not about you. That this is something collective. We are tapping into something that's bigger than us with having these conversations and engaging in this work.

Greg Dalton: That was Kyle Gracey, Slater Jewell-Kemker, and Alec Loorz.

Ariana Brocious: And Greg, can I add just one more thing?

Greg Dalton: Ha, sure.

Ariana Brocious: there’s another big action that most of us can take, and that’s to vote.

Greg Dalton: Yes! According to the Economist, this year the most people EVER will go to polls around the world.

Ariana Brocious: Seems simple, but it’s critical to keep climate front and center among elected officials up and down the ballot. And in the runup to the U.S. presidential election we are going to check in from time to time with politicians and analysts on how the politics of energy are playing this cycle.

Greg Dalton: Today on Climate One... We’ve been talking through a “climate toolkit” for your everyday life. You can find links and more information about everything we talked about in the show notes on our website. And you can subscribe to our podcast wherever you get your pods.

Ariana Brocious: Talking about climate can be hard-- AND it’s critical to address the transitions we need to make in all parts of society. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. You can do it right now on your device. You can also help by sending a link to this episode to a friend. On our new website you can create and share playlists focused on topics including food, energy, EVs, activism. By sharing you can help people have their own deeper climate conversations.

Greg Dalton: Brad Marshland is our senior producer; Our managing director is Jenny Park. Ariana Brocious is co-host, editor and producer. Austin Colón is producer and editor. Megan Biscieglia is our production manager. Wency Shaida is our development manager, Ben Testani is our communications manager. Jenny Lawton is our consulting producer. Our theme music was composed by George Young. Gloria Duffy and Philip Yun are co-CEOs of The Commonwealth Club World Affairs, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.