Greg Dalton: I'm Greg Dalton. And today on Climate One, our topic is the news media and the story of carbon pollution. In the 25 years since the first congressional testimony about human cause global warming, the fundamental science has become more clear. Abnormal climate change is happening and humans are causing much of it. But mainstream news coverage often indicates that science is not subtle. One reason is that fossil fuel companies have manufactured doubt about climate science but that's not the only reason why mounting data has not led to mounting political pressure to stabilize the earth’s life support system. Over the next hour, we’ll look at the competing narratives on climate change with our live audience here at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco.

We’re pleased to have with us three communication experts with a deep knowledge of the carbon story.

Bud Ward is Editor of the Yale Forum on Climate Change & The Media and a co-founder of the Society of Environmental Journalists.

John Cook is Founder of Skeptical Science and co-author of

Climate Change Denial: Heads in the Sand.

Jim Hoggan is Co-founder of DeSmog Blog, author of the book

Climate Cover-Up: The Crusade to Deny Global Warming, he's also chair of the David Suzuki Foundation. Please welcome them to Climate one.

[Applause]

Gentlemen, thank you for coming.

Bud Ward, let's begin with you. About 23-24 years ago, Jim Hansen and Steve Schneider went and testified before Congress. You founded the Society of Environmental Journalists. What's the headline or the narrative arc of the story the last 20-25 years on climate change?

Bud Ward: Well, I think the climate situation has gotten worse. I think we’re starting to run out of time for the kinds of reforms and ways to address the issue that we should have been taking years ago. At the same time I think it's increasingly becoming part of our everyday culture. I think there are some good news, some good activities going on amidst all the bad news that basically involves the lack of federal initiative and the lack of international initiative. But there are some good things happening, some important things happening.

Greg Dalton: And we’ll get to the good news. But first,

Jim Hoggan, how do you see the narrative the last 20 years or so? Have things become more serious? What's the headline?

Jim Hoggan: I think that — what's troubled me is this kind of fake debate, not so much about the debate itself because I think facts are not really as much of a part of the problem as we believe they are but it's more the sort of underlying social dynamic of that narrative that's a problem, and that is that people have come to believe that if you think climate change is a problem or if you think it's not a problem that there's count — it's almost like there's — this is what people like us believe and if you don’t think this, then you're one of them.

Greg Dalton: So it's sociology in tribal, in a way, or a group.

Jim Hoggan: That's right. So underlying the narrative of there being a debate because of the way that climate change denial has sort of unfolded in the way that advocates for change on climate change policies have kind of fought, that you basically have this ideological polarization where people — it's now a matter of identify. And so we have conversations with scientists and advocates that believe that “Well, you just need to explain this more clearly because something is not understood here.”

But if you look at it closer, it's actually not about more information. It's really about this sort of identity conflict. And so I think that the way the narrative has unfolded and the way it unfolds right now, it reinforces this polarization but it's not a good kind of polarization. It's not a polarization that takes you to a greater understanding. It's a polarization that takes you to greater gridlock.

Greg Dalton: And what's the solution then to change that — to get that identity foundation that you're talking about?

Jim Hoggan: For me, I'm a communications guy. And one of the things that I've learned in speaking to people about this social scientist in particular or something I've decided myself, I wouldn't attribute this to the people I've spoken to necessarily but I've come to believe that you need to approach these types of issues with something in the back of your mind that probably when we were younger and we've forgotten as we gotten older, and that is that you could be wrong. That we need to have an eye on intellectual modesty in these issues because if self-righteousness takes over, it reinforces this kind of ideological polarization. And the self-righteousness can take — just because you're right doesn’t get you off the hook. You can be right and self-righteous. You can be right and polarizing. You can be correct on the issues and correct on the science, correct on the emergency but totally wrong on how you move the issue forward because of your self-righteousness.

Greg Dalton: John Cook, you have a site called Skeptical Science that has a top 10 myths of people who sort of don’t accept climate change.

Do you think that there's maybe a little tone of what

Jim Hoggan was just saying about that in your site, like “Here's the truth,” the other people, “Here's how to talk to stupid people who don’t accept the facts”?

John Cook: Well, one thing I always stress is that it's not about stupidity, it's not — like people who reject climate science — and there's a lot of evidence to say that it's not necessarily due to a lack of knowledge or due to…

Greg Dalton: Intelligence even.

John Cook: Yes, exactly. Or even level of education. And as he say, the biggest dropping factor is cultural factors, is political ideology but that's also not the whole story either like talking about the last 20-25 years. What we've looked at is how has our understanding of science evolved over that time. And among climate scientists, it just gotten stronger, our confidence that humans are causing global warming but among the public, they don’t — there's a very large perception that the scientist agree.

And the interesting thing is that there's a big cultural factor in that large perception of consensus. I can say that they’re much more likely to think that climate scientists disagree than liberals. But there's still a large perception of consensus among liberals so I think there's a mix of culture and a mix of every information deficit or meet the information circles.

Greg Dalton: So why is that? Is it because the information is not getting out there? Is it because of deliberate misinformation, fossil fuel funded, smog and clouding the science? Is that a factor?

John Cook: I guess the answer to that is yes.

Greg Dalton: All of those?

John Cook: Yes. And for the last 20 years plus, there's been a very strong effort to cast that on the consensus. And it goes back as early as 1991 or even earlier when some fuel associations spent half million dollars on a campaign to reposition fact as theory and to cast that on the settled facts of climate change.

And since then, it hasn’t been all fossil fuel. There's been ideological groups and just various attempts to I guess confuse the public about the fact that scientists have been agreeing on this for decades.

Greg Dalton: There’s a book,

Merchants of Doubt, that told that story that's now going to be made into a film by Jeff Skoll. Look for that next year.

Jim Hoggan, is fossil fuel money? Have they been driving the narrative?

Jim Hoggan: Absolutely. I mean, I think there are people in the fossil fuel industry that I believe at one time or another are going to be sitting in those same seats that the tobacco industry sat in and having to account for some very tough questions about information that they knew and acted against the public interest and against massive public interest with climate change.

But I think there's an equal accountability on the part of environmental advocates when you believe that the reason that people don’t agree with you is that they don’t understand, when the real reason they don’t agree with you is because they don’t think that people like them should think like you and you go on to communicate in a “I'm right, you’re wrong, let me tell you what you should think” manner. This basically actually makes — if what you want is actually a solution, this is setting aside being right or setting aside winning or the sort of satisfaction that comes with somebody being wrong about something. But if you actually want something done, then I think there's sort of an equal responsibility on the part of both climate change denial and the kind of mischief that you see from the ideological right and people who are advocating for change.

Greg Dalton: When you mentioned that, I thought of Al Gore’s campaign initially. Remember he had Nancy Pelosi and Newt Gingrich, Al Sharpton, a bunch of people from political opposites sit on a chair, spend a lot of money advertising this. And the purpose really was let's show that we can reach across the aisle, come together on this issue and it unifies. And that was later ridiculed as being naïve or ineffective.

Jim Hoggan.

Jim Hoggan: Good idea may be wrong format, but it's a good idea to have — if you have that kind of polarization that I'm talking about, the last thing you need for Republicans is Al Gore as a spokesperson. I love Al Gore and we all should admire him for what he's done for this issue but there's a downside to Al Gore if you need people who you disagree with, you don’t like on the other side, agreeing with you in some way, right? He's a polarizing figure for Republicans. And so I think that there's a need to have people on that side of the issue speaking to people on that side of the issue in a manner that is comfortable for them in the paradigm that they see the world through.

Greg Dalton: I interviewed Arnold Schwarzenegger five times when he was in office, and I always thought he was a better communicator because a lot of people would listen to Arnold who wouldn't listen to Al Gore. Whatever Al Gore said, certain people are going to dismiss it before he — regardless, just because he said it.

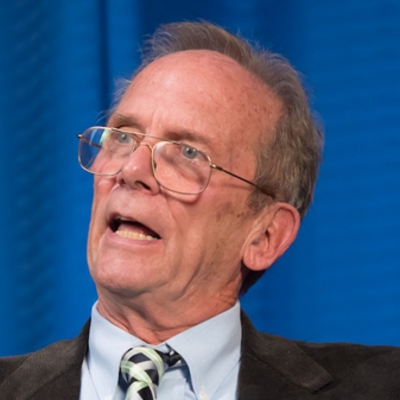

Bud Ward, let's get you in here on terms of the mainstream news coverage of this debate and how the mainstream news has covered this polarization.

Bud Ward: Well, I'm reminded about a week ago, Tony Leiserowitz at Yale who I work with asked me who the 10 top reporters in the country were on climate.

And to be honest, I couldn't come up with 10. I got to five or six and then I started going into niche media, which are important, but they're not what he had in mind. And after you get past two or three — I mean, at major metropolitan dailies you’re past two, three or four in the United States, the trough runs dry pretty quickly. And this is not true only of mainstream coverage of climate. As important as climate is, there are other important public policy issues that are also being totally ignored or disregarded by the mainstream media. So I think we have kind of a perfect storm with this issue which communications scholars have referred to as a wicked issue, a great term for it, because of the difficulty in communicating about it coming at a time when the media for distribution of information to many of Americans including local television have withered to — I mean frankly, the New York Times isn't nearly the paper it was 10 years ago. It may still be the best single daily newspaper in the United States, in my opinion, it is, but it's no nowhere near what it was 10 years ago, let alone Time Magazine, News Week, US News & World Report. I mean, they're just not. So it's been a strange confluence of the major issue needing this kind of information and diversity arising at a time when the media are just not capable of covering it anymore.

Greg Dalton: On the New York Times, the New York Times’ public editor recently did a piece on New York Times climate coverage. In 2013 the New York Times did away with the screen blog.

It disbanded its environmental desk. And this happens as the Wall Street Journal no longer has environmental reporter. He now works at Stanford. KQED disbanded its Climate Watch and there's been other. One guy moved from USA Today to National Geographic. And the public editor of the New York Times quantified this and said that quantity had dropped and the quality had dropped of deep enterprising coverage. So let's talk about whether the niche players, Climate One, Grist, Climate Progress, et cetera, can they feel this void,

Bud Ward, or is it just like just trying to put pebbles into a big hole where…

Bud Ward: I think we’re at the beginning stage of what's going to be a 40 or 50-year evolution of media and information and how we go about getting our information. I think there's great potential in the so-called new media. I think there are important voids that they are not yet filling that are being left by the demise, if you will, of the traditional or mainstream news media. And with all the damage that the mainstream news media did to themselves and all the neglected outstanding that they could have provided — I mean, they brought this on themselves in lots of ways. But some of the virtues that they provided to an informed democracy are not yet being filled, in my mind, by the new media.

There's potential but I think we’re at a real risk of furthering the information gap just like the income gap in the United States and other countries. We’re at a real risk of furthering the information gap. If you really want to know about climate change, you can pretty much be very knowledgably informed by trolling the web intelligently and getting outstanding information, but you've got to go to it. It doesn’t come to you. And that runs all the risk of the information gap arising anew on this issue and other issues.

Greg Dalton: Bud Ward is Editor of the Yale Forum on Climate Change & The Media. We’re talking about media and climate at Climate One.

Jim Hoggan, can niche players fill the big gap of the metro dailies in the travailing mainstream media?

Jim Hoggan: I started DeSmog Blog quite a while ago. And so I would say it's been, for me, astounding that a small group of people could have such a big audience.

Greg Dalton: And what is the audience?

Jim Hoggan: Well, that's what I was going to say. Big audience for us — if we have a really good day, we might get 70,000 readers a piece, right? Most days are a lot less than that. But then there's this kind of odd thing that happens is in social media when you have lots of friends who respect you, they'll take your stuff and push it out on theirs, right? So you've got not just one blog that has 50,000 readers in a particular day, but then you've got a whole bunch. And before you know it, you've got actually millions of people. You actually have readership that's bigger than our daily newspaper.

The problem is that the people who read it are probably not the people who need to. And there tends to be, the way — there's a guy that I interviewed for a new book I'm writing named Jonathan Haidt who says, “Morality both binds and blinds us.” So we have these kinds of moral views of the world that pull us together in teams and pit us against other teams and blind us to the truth. And there's no better place to just expose yourself to what you already think than blogs and online media and to have it just reinforce what you already think and never be exposed to the reality of somebody else.

I mean, just because somebody doesn’t think that climate change is a big problem as I think it is, doesn’t mean they're a crazy person you should never listen to. They may actually have a lot to say. In fact, they probably do but the Internet basically creates this divide — I wonder if that's not what you were talking about.

Bud Ward: Absolutely. I think in this in particular with the loss of Nelson Mandela and how he was able to bring people together — there's a number of us yesterday at a conference here in town listened to former main Republican senator, Olympia Snowe, who was really one of those senators who was able to cross the aisle. And she made the necessary comment. She said she learned an awful lot in her 34 years on Capitol Hill, learned an awful lot from those who she disagreed with. And Mandela and President Obama yesterday made a somewhat similar point. And I think we've lost that. I think that's one of the things we baldy need but I think we've lost that too.

There is no single monopoly on wisdom or intelligence on this issue. We need to have a strong, aggressive debate on what to do about this issue. We don’t need another decade wasted on is it humans, is carbon dioxide a pollutant and is earth warming. We know that. The evidence is compelling. So as strong as it can be, we know that but we need a good hard debate on what to do about it and how soon and how important it is. That's been one of the victims, I think.

Greg Dalton: Let's ask

Jim Hoggan and then

John Cook, what you do, if anything, to try to reach out beyond to acquire, to get people who might not be in the same tribe or mindset.

John Cook, let's ask you first. You try to get people — because it kind of geared — partly skeptical science is geared, here are some clubs you can kind of knock some sense into deniers, right?

John Cook: Yes. I guess what we found was the similar experience to what Jim reported.

We found that the biggest impact we make is when other third parties take our content and republish it in other venues. And what it does is reach both a much broader audience than just the people who visit our website who usually are people engaged in the climate issue already, and also much more diverse audience. So we found that our content is being used in university curriculums, so that's going out to university students, in books and university textbooks. So it reaches a lot broader people than just our climate bloggers. And even TV documentaries and shows who would just grab infographics that we would create or arguments that we publish.

And so what we've done realizing that is create our content in a way that makes it as easy as possible for the third parties to republish it and share it around. And also for social media to share it so that one person who reads our site might share it but then their whole network of people will get access to that information.

Greg Dalton: And if they're sharing it to pillory and make fun of it, that's okay? “Well, look what these people or crazy people are saying.”

John Cook: Well, I guess you could argue there's no such thing as a bad publicity.

Jim Hoggan: Yes, that's a good question. I think our site, at least part of my original idea, was to sort of help make people, average people more savvy about how peace time propaganda works, how public — I'm a public relations person. And so what I was trying to do is kind of explain public relations from the oil and gas industry and the coal industry to people. And what I found is that I constantly had to rein in the people who are writing because you get so angry at people who are lying or people who are misleading.

It's very easy to get carried away and to — I guess what I ended up realizing was that I not only had to rein them in, but I had to rein myself in. And what I found is that it's like a lot harder than I thought. And so when I started writing this new book I'm writing called The Polluted Public Square, one of the first people I talked to was a Zen Buddhist Monk named Thich Nhat Hanh. And I spent an hour with him and David Suzuki. And right at the very end of the interview, I said to him “You're not saying that we shouldn't be activists, are you? I mean, you've been — when you were in Vietnam, you were an activist to protect the monks and nuns in your monastery. I know that you used to paste up the faces of bad policeman who were harassing people in your monastery. So it's not like you don’t believe in activism,” because he'd be making these comments that made me wonder about it.

And so he kind of looked at me and I — if you ever met Thich Nhat Hanh, having him look at your is quite an experience. And he was very close, this close, right? And there was this kind of look of kind of like right into my soul kind of look. And he said, “Speak the truth but not to punish.” And ever since he said that — I remember I was walking off the stage and my wife said, “You heard what he said, didn’t you? You heard what he said, right?” And I realized that how easy it is to suffer from that problem. Self-righteousness is like a virus, and a lot of the time it's so subtle you don’t know you have it. And so to get back to your question, that place in people, if you want to reach out beyond the converted is not helpful.

You need to start some place deeper than your mouth in communicating with people because people are not stupid and they know what you're up to and what you're feeling. And if you don’t deal with the inner ecology, the outer ecology doesn’t have a chance. And dealing with the inner ecology is the hardest problem we have, for me anyway, it is.

Greg Dalton: So does that mean that villainization of oil company executives, that sort of thing, is counterproductive?

Jim Hoggan: That's a really hard one. I would say you want to do it mindfully. I think if you think the world is full of evil people and they're surrounding you, you probably have to get your psyche checked rather than these people, right? But I do think that there's been some really bad behavior. I mean, I haven’t close down DeSmog Blog because there's a role for that. But I think you need to be extremely mindful about are you taking the polarization that you're creating into the future or into the past? Are you creating gridlock or understanding?

And there was a rabbi named Hillel who lived around the time of Jesus who talked about debate for the sake of heaven and debate for the sake of defeat, winning. And said — this one is good — heaven means greater insight. We want to have those debates so we can understand better. We don’t want to have debates for the sake of just beating and winning. Those tend to bring out the bad parts of people, right?

And so it's not like this is new. These people have understood this for a long time, right? But we tend to be too busy to sort of be this and not have the time to really check ourselves. And many of us don’t have the relationships that we should have with sort of spiritual sources of self development that allow us to kind of look at ourselves and clean this kind of stuff up. And we can end up being part of the problem even when we’re right about the issue. And I think part of the problem is that when you have the science on your side, it's easy to think you're right and it's easy to overlook bad behavior because people who are opposing it seems so unbelievably unreasonable.

Greg Dalton: John Cook, you do a lot of work looking into the — I'd now use this term with a little bit of hesitation — the denial sphere, people who deny the science. Let's get your response in that frame to what

Jim Hoggan just said about the motivations and the way those people are approached and the way they spread denial.

John Cook: I mean, I think it's quite instructive to consider — to understand the psychology that comes into play when climate change attitudes are involved. And like the question how do you distinguish between someone who’s deliberately misleading and someone who genuinely believes, it's actually extremely difficult, nearly impossible thing to do because the kind of arguments that someone would use to deliberately mislead someone manifest in exactly the same way as the argument someone would use if cognitively bias just pushes them towards these same arguments. So for example — one popular argument that kind of came up earlier was the use of fake experts to cast out on whomever with scientific agreement.

So getting spokespeople who aren't experts in climate science but convey that impression of expertise, and that's a popular tactic to use to portray the impression that this is 50/50 debate among the climate science community. But then if somebody is ideologically biased, they just have a tendency to attribute more expertise to people who they agree with. And so it manifests in the same way they consider these non-experts are experts in climate change as a genuine belief. So I tend to examine the behavior rather than the motive behind it. If someone is misinforming people, you can't comment on whether they're lying or whether they genuinely believe it. You just have to address the behavior.

Greg Dalton: Let's talk about Fox News. What role does Fox News —

Jim Hoggan and then I'd like to get

Bud Ward on this — play in the climate debate. You've talked about that a little bit.

Jim Hoggan: This is just my opinion — well, it's actually not my opinion. It's an opinion of a guy that I interviewed named Jason Stanley. And he said, specifically about Fox News, that he and a bunch of his friends were sitting around having dinner one night, and they were talking about Fox News and this tagline of fair and balanced. And he said his friends were saying, “Do you know anybody who thinks Fox News is fair and balanced?” And no one named anyone. And then they go on to talk about “Would you actually think Fox News thinks that they're fair and balanced?” Probably not. And so what is this about? And so his view is that they're not actually trying to convince you that they're fair and balanced, they're trying to convince you that nobody is. And that is like really, really dangerous because that's essentially saying there are no such thing as facts.

There is no such thing as objectivity. You can't believe what anybody is saying because everybody is just out to manipulate you for their own purposes. So why would you even go to the public square? Why bother? And if you ask me what the biggest problem of climate change, inaction on climate change is, it's not climate change denial, it's that people have just turned off. They basically — Deborah Tannen says you hear a ruckus outside your window, you open the window to find out what's going on. Unless there's a ruckus every night, and then you do the opposite. You just kind like button down the hatches and ignore it. That sort of disinterest and mistrust and public disengagement because of all the racket is a bigger problem than climate change denial. Sorry. I totally forgot the other question.

Bud Ward: Well, I agree with a lot of what Jim said there. I think that there are a lot of editors around the country who are experiencing what I'll call climate fatigue. They've been on this issue for 20-25 years. It's a good day-one story. It's a lousy day-two story. And most editors worth their salt would kill to have a — now, listen carefully — to have a well researched, well-reported, well-documented, well-sourced, beautifully laid out story saying it's a hoax. If that story exists, that's a Pulitzer and I want my byline on it. Unfortunately, the story doesn’t exist. You can't do it but most journalists who are _____ [00:31:43] there still are some out there who would kill to have that story. I think the demographics of the Fox News audience says a lot. It's clearly an audience that's predisposed to accept a lot, not all, of what Fox News does. And I'd say just like the media isn't monolithic, even Fox News isn't monolithic.

Their talk shows are clearly off the scales to the right, if you will, and full of errors, probably deliberate errors, on climate and climate science. That's not necessarily the case with all of their news programming. It's certainly not the case with your local Fox affiliate. You're local Fox affiliate may be treating this issue fairly responsibly and they have a lot of discretion to do that. So even Fox News is not monolithic. But some of the criticisms that I would apply to Fox News, frankly, I would apply that to MSNBC also. So I think both of them apart from both of your houses, a bit stronger parts, frankly, on Fox than on MSNBC. But saying that, it doesn’t leave the three legacy networks, ABC, CBS and NBC, in the U.S. much better. They still have problems with this issue too.

And I'd say, clearly, PBS stands above the rest in terms of its coverage of this issue although it's far from perfect. And even the News Hour, what used to be Larry News Hour, recently created a major blunder with what Jim was referring to earlier when he referred to the false balance. So even PBS is not above it. It's a tough issue to cover.

Greg Dalton: We talked earlier about some positive stories. So I'd like to offer one and then get your comments on some of the bright stories that might have been told or need to be retold. And one that comes first to me is Tesla. Tesla is an amazing success story. It's sexy. It's changed people’s perceptions of what electric cars are. A lot of people who don’t care about polar bears or climate love it for its technological sophistication. It's cool and it's a great story and a great — a year ago, I might have bet that Tesla might not make it.

So

Bud Ward, what are some other positive stories that had been told or need to be told more?

Bud Ward: One of the New York Times front page, the piece the other day talking about major corporations, two dozen, two and a half dozen who are basically getting very serious about factoring the strong likelihood that there's going to be carbon tax in our lifetime, certainly we hope in our lifetime, factoring that into their economics it was given.

I thought Jim’s comment was right on when he said earlier that the closer you get to the people, the more good news there is and more good activity there is. And I certainly agree with that. There are some amazingly encouraging things going on to address this issue independent of the stalemate in Washington D.C. on moving forward with this issue. It's happening at community level. It's happening in certain corporations. It's happening at boardrooms. It's certainly happening in the insurance industry. So there are some really encouraging signs, it's just, frankly, not enough.

Greg Dalton: And those are stories on the business pages, not necessarily on the environmental pages.

Jim Hoggan, positive stories.

Jim Hoggan: I have them. I was just trying to think of one. I told you about UBC and how they're going to exceed their…

Greg Dalton: University of British Columbia.

Jim Hoggan: And that's a very positive story and it continues with retrofitting and various kinds of shifts in the type of fuels they're using. UBC is the University of British Columbia. But I think there's something else that's even more positive, and this is something Peter Senge is very, very interested in, and that's young people. And the way — if you ever get a chance to meet him, he's an amazing man at MIT, a systems thinker who’s very concerned about climate change. And he's very interested in young people. So he does a lot of work in education.

And one of the things that I've noticed in universities across Canada is that students coming into universities are demanding that sustainability be folded into any of the faculties that they're going into. So it's in law — at UBC there is sustainability in the law faculty, in engineering. And so you see this — really, when you think about sustainability, sustainability is actually about young people. And young people don’t have the problem that a lot of older people do in sort of pulling all this together. And so I think there's a lot of really interesting progressive things happening with young people. And certainly in universities across Canada, from McGill to UBC to Simon Fraser and University of Victoria are changing their curriculum to help people better understand how we practice law and engineering and all these other amazing things that we do in a more sustainable manner.

John Cook: Well, Jim and I were having a competition earlier on who is worse, Australia or Canada at the moment. I think Australia wins hand down.

Greg Dalton: In terms of being a dirty fuel economy?

John Cook: Well, just the general direction, I guess, of the government and how supportive they are of climate action. The one thing that is encouraging in Australia is just the way renewable process have dropped so sharply, like solar power is so much cheaper than it was back when we got our solar panels on the roof. And even friends of ours who don’t really accept the science of climate change are still asking us about solar panels and just interested in it from an economic point of view. And I got into big discussions with my dad for quite a while ahead of climate change and he too wasn’t really that accepting of the science but he crunched the numbers and got solar panels on his roof because it just made financial sense. And then the funny thing was afterwards, suddenly he accepted the science, and it was the behavior change that drove the attitude change that shows that human mind has a bit of complicated crazy things, not just one factor that drives what we believe.

Greg Dalton: We've had people here talk about that. If you take one action, you're more like to take another action. So that first step opens the door to lots of things. The Keystone Pipeline has been on the front pages a lot. It continues to be sort of an icon of the climate debate, et cetera. Let's talk about that as a news story both as a communications piece as well as something that has all the elements in here.

Bud Ward, Keystone Pipeline gets lots of coverage. How would you analyze the coverage of it?

Bud Ward: Well, I think the coverage is going to continue to emerge and it's a tough issue for the media because it has become and has been made such an icon. Probably how we do as world society in addressing climate change is even bigger than the question of what we do about Keystone. Whether the President decides to proceed or not to proceed from the U.S. standpoint with Keystone, we’re going to still have major challenges whichever way he goes on that issue.

I would say one thing, Greg, in the discussion of good news. I think it's important that we recognize that we've come through a period the past seven years or so in which we had an administration in Washington, which came in strongly committed and strongly knowledgeable on this issue. It came in for a time being with majority controlling both houses of congress. It decided not to pursue this issue as its highest priority. It has basically gone mute on this issue to a large extent. There's absolutely no prospect of federal action outside of the regulatory area, the main EPA regulation of coal-fired power plants. And we wouldn't have guessed at the first inauguration that we'd be sitting back and saying, “We've gone nowhere on this issue.”

And I think that's a bit of sobering news. The U.S. leadership that we once exerted in the world on environmental issues broadly is completely gone. It's just no U.S. leadership. As a matter of fact, I'd suggest that there's no U.S. leader. I mean, who is the leader on climate change in the United States Senate or the United States Congress? We don’t have an Ed Muskie like we used to have. And there are some decent people but there's no U.S. leader. I agree with the comments that were made earlier about Al Gore. He's terrific. We couldn't have done it without him but he's the wrong leader right now. He's the wrong face on the image.

Greg Dalton: It used to be John McCain. That changed. It sounds like you don’t put much faith in the President’s climate plan that he announced in his speech in Washington earlier this year.

Bud Ward: I put lots of interest in speeches but I think I'd rather see the action than the speeches. And there had been some decent speeches, some are earlier. But remember, this is a guy who can and still does as I’ve witnessed just yesterday, make terrific speeches but he's not chosen to use the use the bully pulpit and for a long time there was a mask on this issue. Don’t talk about climate, certainly coming into the last elections. So I think they've kind of blown some opportunities.

Greg Dalton: Jim Hoggan, President Obama as a climate communicator?

Jim Hoggan: I'm yet to be convinced that liberals are better on the environment than conservatives.

Greg Dalton: George Shultz was here a couple of weeks ago. He reminded us that it was under President Nixon the EPA was created, Clean Water Act, Clean Air Act, that they actually — and then Montreal Protocol. He says conservatives actually get things done. What have Democrats done?

Jim Hoggan: John Fraser who is the minister of the environment in a conservative government in Canada was part of the Montreal Protocol, which, if you believe the New York Times this morning, has contributed a lot to mitigation of climate change, also behind acid rain — action on acid rain.

So I think that there's a — to go back to the Keystone Pipeline, it is not a good idea to say yes to the Keystone Pipeline because I think it endorses bad behavior. Our government in Canada, and I say this as an individual citizen, not as chair of the David Suzuki Foundation, but our government has not done anything on climate change. It needs to do something on climate change. If we said yes to the Keystone Pipeline, we would be saying yes to bullying, we would be saying yes to complete disregard for the need to clean up and reduce — clean up the tar sands, the oil sands, and reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The real problem, I think, for the Keystone Pipeline is not Bill McKibben. It's Stephen Harper with that ideological…

Greg Dalton: Prime minister of Canada.

Jim Hoggan: Right. The ideological response to climate change. Advertising does not reduce greenhouse gas emissions. And if you lived in Canada, you would think it did, right? And so I think — anyway, I don’t know if that's where you're going with your question but that's certainly what I think about Keystone Pipeline.

Greg Dalton: You're a savvy communicator. You can take my question whatever direction you want. You know that. So we’re going to pause for a moment and invite your participation. We’re going to bring up the microphone and invite you to come join us and hope you will come on and don’t be shy to come up and join us. While we’re doing that, I want to — it’s going to come around, I’ve got some people come in. So have you come on up and…

Bud Ward: Greg, can I briefly — with all due respect to George Shultz and all he's brought to this issue, there is one factual point that I'd like to correct.

The Republican Party does deserve a lot of early credit for passing some of those neighboring laws and legislation. The National Environmental Policy Act, which Nixon declared, the environmental decade, the Clean Air Actually, but I think you mentioned also the Clean Water Act. And the Clean Water Act was actually vetoed by President Nixon and had to be overwritten by the U.S. Senate, the Democratic Senate at the time. So I wouldn't give the Nixon administration as much credit for the Clean Water Act as it might have deserved in some of the other areas.

Greg Dalton: That was probably me not him that's making that mistake. Thanks for that correction. Welcome to Climate One. Let's have our next question — first question. Welcome.

Raleigh McLemore: I'm Raleigh McLemore. I'm a retired science teacher here in California. Science teachers really represent a potential public opinion making force. And they're confronted with some of the noise that you're hearing whether we get an article from a parent that says the Antarctic ice sheet is growing so what you're teaching my son or daughter is wrong. And from the U.K. Daily Mail that's the most recent one I saw from a guy named Charlie — I think his name is Rose.

Often times the people who are giving us this information are really good parents who are trying to find out what's right or wrong. They're not usually ideologues, I don’t think, but it often leaves the teacher who has, I think, sometimes the bare minimum knowledge about climate change. I mean, we’re teaching what we know but we don’t know all of it, right? So sometimes it really throws us for a loop.

Greg Dalton: Did you have a question?

Raleigh McLemore: The question is — sorry. Well, actually it's more of a statement. Make sure that you reach towards those thousands of people who are teaching climate change everyday. Don’t forget us. And sometimes it helps — like National Science Center for Science Education is doing this trying to actively train teachers on how to teach climate change.

The Heartland Foundation just sent out massive mailing to everybody saying how climate change is wrong. And I don’t see the other side to it.

Greg Dalton: Thank you. Anyone who want to tackle that?

John Cook.

John Cook: The American Geophysical Union is holding a full meeting conference this week. And I'm actually talking there tomorrow on this topic about the problem of misinformation and how the teachers deal with it. And one approach that I'm suggesting is that addressing this information in the classroom is actually a powerful education opportunity because education isn't just about pouring new information into students’ heads and so about correcting misconceptions that they have. And the most effective way of correcting misconception is to actually activate that misconception in the classroom and then replace it with the correct conception.

Greg Dalton: Teachable moment rather than something to be just swept away.

John Cook: That's right. So there are two decades of research into this area. It finds that addressing misconceptions directly head on and explicitly in the classroom is actually a powerful educational opportunity.

Jim Hoggan: Yes. And I think that part of it is to try to not focus solely on the good versus evil behavior type of narrative. It seems to me that exploring the motivation — so when I did the book tour for

Climate Cover-Up people would say, “How can these people sleep at night? What motivates them to do this?” And I didn’t know — a lot of the time I don’t know the answer to that, what's going on in somebody’s mind. I used to say money, it seems to me, to be the most obvious, money and ideology, right? But actually taking it a little bit deeper and starting to look at the kind of social psychology of how people behave in groups.

And there's a great book — where are you who are just — oh, right there. Yes. There's a fantastic book written by a woman from L.A. named Carol Tavris called Mistakes Were Made (But Not by Me). She explains the social psychology of this type of denial in a way that is clear, that people self justify. It doesn’t matter whether you're on the left or you're on the right, we all self justify. We make a decision and then we look for all sorts of reasons for why that decision was right. We don’t like to admit we’re wrong and we especially don’t like to do it in public. And when somebody else is attacking us, we even don’t want to do it. We don’t want to do it even more so.

And so people understanding the kind of social psychology — students understanding the social psychology of what's behind this is important because people who lie in leadership positions are dangerous people. But people who suffer from this type of self-justification, this avoidance of cognitive dissonance, these are people who are way more dangerous because they cannot self-correct. The person who’s a liar, “I did not sleep with that woman,” they kind of know they're lying. They're less dangerous than the person who’s first lied to themselves and now they're going to lie to you and sort of going into a kind of — as an educator — into an understanding of that, to me, would be really valuable for a young person to understand that.

Greg Dalton: Jim Hoggan is Co-founder of DeSmog Blog. Let's have our next audience question. Welcome to Climate One.

John Mashey: John Mashey here right for DeSmog Blog and do work with Skeptical Science. So a question was sort of alluded to but maybe you want to address some more is the odd connections with the tobacco industry. I came up in Merchants of Doubt, it was discovered last year, actually, by folks at U.C. San Francisco that the tea party was basically constructed not just by the Koch Brothers but by the tobacco industry. And that story broke in the DeSmog Blog.

So anyway, could you guys address that in terms of the public relations techniques used and any other relations? I think it varies by country so maybe you can say a little bit about that.

Greg Dalton: Let’s just tackle that quickly? Tobacco and oil.

John Cook.

John Cook: I'd say one quick thing about it. I think as a communicator, there's a powerful story there, and it's a story that resonates with people, this story that the tobacco industry misled people about the link between smoking and lung cancer, and the same techniques are being used today about climate change. Our people know about the health problems with tobacco. And so by joining the dots between those misleading techniques and what's happening now, it's a way to tell a human story to put the climate controversy in context.

Greg Dalton: You know Russell Crowe movie. Oil people really bristle at being associated or compared to tobacco. I noticed it really gets under their skin. Anything else on that?

Jim Hoggan: Yes. And I knew that. In DeSmog Blog that's one of our key narratives, is trying to show the relationship. And the advancement that's on Science Coalition was one of the original organizations that passed on what was learned on behalf of Philip Morris about creating doubt in public thinking about cancer and cigarettes to climate change issues so that — and the idea is through a bunch of technique, things that we call like AstroTurfing, we call it ventriloquism.

So you're basically — an AstroTurf is like a — AstroTurf group is like a fake grassroots organization. Ventriloquism is basically putting a white lab coat on somebody and giving the sort of corporate sort of speaking points, delivering them through that person. But right at the very bottom of this problem is — these people use social science. These people know how to take advantage of the cracks in the way people think, and they play with that. And people need to understand how that process works especially something that George Lakoff talks a lot about is the power of repetition, repetition of even false ideas. It goes all the way back to the Second World War where you — this sort of demonization of people that you basically — they knew, they learned these things over and over and over again. And even if you don’t trust the source of it, there's research that shows that it actually has an impact on the way you think about things.

So I think that is another area that we need to better understand, not just climate science, not just the social psychology of this, but also how does propaganda work. Propaganda is more than just name-calling. There is such a thing as propaganda. It has been studied, academics have looked at it, it has a history, there are techniques, they are successful in manipulating people, and they can be used on behalf of the tobacco industry, on behalf of the fossil fuel industry or some kind of evil political belief.

John Cook: Just to follow up on what Jim’s talking about too. I think a really useful approach is to help people — give them the skills to detect propaganda. And one of the social science experiments I've recently performed is testing the effect of explaining the tobacco industry tactics and then joining the dots between that and what's happening with climate change.

And what I found was priming people and then showing them this information, it either neutralizes the misinformation or it can cause it to backfire.

Greg Dalton: Let's have our next question. Welcome to Climate One.

Peter Joseph: I want to thank all of you for this great intelligent discussion and your individual work. My name is Peter Joseph. I work with Citizens Climate Lobby. We’re advocating a revenue neutral carbon tax. And I want to know what your opinion is of its chances and how it might work to counter some of the psychology and the propaganda that's been out there for so long. It seems that money is a universal substance that everybody understands. And as long as carbon pollution is profitable, it's seems like it's going to happen. But as soon as it becomes clear that it will become less and less profitable through a carbon tax that's rising, that there will be a psychological shift in people’s understandings of the whole energy economy. I'd like to know what you think of that.

Greg Dalton: Cap and trade was political poison. Now carbon tax seems to be getting some traction. Who would like to —

Bud Ward.

Bud Ward: Well, I would say the work of the Citizens Climate Lobby is really quite interesting. There's a fairly new adventure, a fairly new grassroots issue by the map. I think it does make a case that should and could appeal to political conservatives, if you will. I think it has lots of merit behind it. I think, quite frankly, cap and trade was a disaster. And it may be a good thing that we didn’t pass cap and trade. Of course, we need to pass something but I agreed with some of the comments at the time that this was the worst legislation I've ever seen. Let's pass it right away because we needed something. We needed to get started. And we didn’t pass it, of course.

But I think there are some real winning arguments that can appeal across the isle. And I think this kind of — I mean, we’re going to have a carbon tax at some point in our history, hopefully sooner rather than later. And we still have to get over the scars from the cap and trade battle and there are very few relationships. I mean, I assure you, regardless of what your position is on climate change, your mind is fairly aggressive towards controlling it. I would be troubled going to my member of congress in many, many districts across the United States, in many, many states across the United States and say it's in our political personal best interest to support cap and trade. It's a tough sell even if you really need to do something about this issue.

I think the approach CCL is taking has a lot of merit. And I think it's winning some support in some conservative quarters. Most of all, in my home in Virginia, very, very conservative. Richmond Times Dispatch newspaper, its editorial pages is leaning to the right of the Wall Street Journal and always has been. And it came out and basically said within the past six weeks, eight weeks that science is real. We got to get on this. Forget about the debate. Forget about the denialism or whatever you want to call it. The science is real.

Greg Dalton: Some of those editors probably have homes on the Virginia shore.

Jim Hoggan.

Jim Hoggan: Yes. Well, we have carbon tax in British Columbia where I'm from. And it was put in place by a — basically a right of center premier who kind of shocked everyone. And so I would say one of the lessons — although it's not perfect, there are some pretty good policies not just the pricing on carbon but climate policies in general. They're being sort of nibbled away out for other reasons but it's very different if you have somebody on the right who no one would expect to do it than somebody on the left.

So when you see somebody on the left do it, that's what you expect from that kind of ideological point of view but you don’t expect somebody on the right who would do it at the cost of their political skin. So it has people scratching their heads, which is, I think these days, a good thing. And so find somebody on the right would be my advice.

Bud Ward: This is the old mix that goes to China’s story. No Democrat could have done to China what Nixon did. And probably no Democrat can come out and support — liberal Democratic — can come out and support — doing something cap and trade. We probably need a really smart Republican legislature.

Greg Dalton: President Christie. Next question.

Female Participant 1: Greg, I was here with your program with James Hansen earlier. And we all know we have a very small window of opportunity available to us. And I'm a grandmother to 11 grandchildren. And I'm not hearing a way forward — I'm sorry — from this group. It's a nice discussion but it's not a way forward. And Bill McKibben’s name was mentioned. Maybe I picked up somewhat derogatorily but he is an activist. And I'm not hearing a lot about activism. And a lot of people believe that forget about the people at the top. It has to be a ground swell of activist around the world. Bill McKibben is trying to make that happen. So I'm getting impatient. What do you think about the role of activism in taking advantage of this small window of opportunity before discussion over? Thank you.

Greg Dalton: Jim Hoggan, without advocates, environmentalist, Bill McKibben and others, we may not be where we are. We wouldn't know what we know.

Jim Hoggan: Absolutely. And certainly I would not want to — being chair of the David Suzuki Foundation, we have our version of Bill McKibben in Canada of David Suzuki. And he's certainly an activist. And I admire Bill. But I think that — let me tell you what the Dalai Lama told me about this. He said — I asked him if he had any advice for climate scientists when I interviewed him. And he said that when he first started talking about compassion, it was like 39 years ago, and that — so he's just been — he said, “I've just been saying the same thing over and over and over and over again for 39 years. And I only feel like now people are actually starting to listen. And I see a response from people interested in compassion.”

And then he said, “We have a saying in Tibet that if you fail, if you fall down, get up, try again. If you fall down twice, get up again, try again. Nine times fall down, nine times get up.” And he said, without going into the details, he went into something about messaging. But right at the end, we get up, the interview is and we’re leaving the room, and he reaches out and tries to touch my forehead with his finger, at least that's what I thought he was doing, and he said, ‘We like to think the western mind is more sophisticated but I think the Tibetan heart might be stronger.” Maybe if we get the Tibetan heart, the eastern heart to work with the western mind, that maybe we can solve this climate change problem. And I think that one of the big things that's missing in the whole narrative and in this exercising moving forward is that people mistakenly think that this is a conversation about evidence, when in fact that's only part of the conversation.

The main part of the conversation has to be about values and it has to be emotional. There has to be an emotional dialog where there's no meaning. Evidence doesn’t create a lot of meaning. Fear maybe, hatred, anger, these things are not the future. I think you need more of an emotional dialog that actually allows people to understand what is the emotional alternative to “I can't make a difference”? What is the emotional alternative to “We are doomed” of the fear that people feel about this issue, the despair that people feel about this issue? That is the conversation that, I think, moves us forward.

Greg Dalton: And we have to end it here. Before we end, I want to ask you each briefly coming back to, we talked about a lot of issues, what people can do individually. We like to give people something they walk out of here with. What do each of you do to manage your own carbon footprint and what's the next action you will take to reduce your carbon footprint?

John Cook.

John Cook: I guess what I do is — I guess there's not a single answer to that. There's been a series of steps and just gradually…

Greg Dalton: It's a ladder. Constantly climbing up a ladder. What's the next round on your ladder?

John Cook: It's an incremental wheedling down of everything I have time and so getting solar power, even with just a matter picking up the phone and asking my electricity provider to switch to green energy. So in one action this reduces the hash footprint to nothing, and it's a fairly minimum cost, at least in Australia it is. So I guess, yes, it's just been a journey of reducing the footprint.

Greg Dalton: It's a continual process.

Jim Hoggan.

Jim Hoggan: Rail against the system, right? I mean, I think the kind of thing we’re doing right here is an exercise in trying to reduce our carbon footprint, this conversation. But I eat less meat. I drive a hybrid. I consume a lot less. I do the kinds of things with energy. Sadly, where I'm from, solar panels have kind of a minimal impact. But I do those kinds of things. That is not the solution. Those are just things that you can do so you're not a hypocrite but the real solution is at a bigger systems level. And we need to hold politicians accountable especially help politicians who actually want to make a difference.

Bud Ward: Well, I agree with all the things Jim just mentioned about things you do personally. But the other thing I do personally, and this goes back to the last question about you wondering where the fast-forward is, is it too late. It's not too late. I think we have to convince our citizens that it's not too late to avoid some of the worst impacts. It is too late to avoid some of the damage but we still have opportunities. If we can only muster the political will and leadership, there are still opportunities to avoid the worst impacts. And that's a ray of hope that I think we have to live it.

It's a real concern that even those on the most concerned end of the spectrum on this issue are starting give up. “It's too late. I can't do anything about it.” Don’t. We can — the best minds are telling us we can still avoid the worse impacts. The question is whether we’ll do it.

Greg Dalton: We have to end it there.

Bud Ward is Editor of the Yale Forum on Climate Change & The Media.

John Cook is Founder of Skeptical Science.

Jim Hoggan is Co-founder of DeSmog Blog. I'm Greg Dalton. You can listen to Podcast of this and other Climate One programs in the iTunes store. Thank you all for coming and thank you for listening.

[Applause]

[END]