Activism, Art and Environmental Justice

Guests

Christine Abadilla Fogarty

Sofía Córdova

Doug Harris

Ladonna Williams

Summary

On Climate One we often try to shine a light on the vast inequities that exist between those who benefit from extracting and burning fossil fuels and those who suffer its impacts first and worst. Art offers a lens for exploring energy and mineral extraction and challenging audiences’ worldviews in ways that can be subtle and disturbing.

With that in mind, we recently hosted a discussion with some of the people behind San Francisco State University’s recent exhibition, Clearly Polluted: The Fight for Environmental Justice in the Bay Area. The show investigates environmental racism and its ongoing, disproportionate impact on Black, Indigenous, and people of color. It was co-curated with community advisors, local activists and advocates who share their lived experiences and ongoing efforts for climate and social justice.

“I think George Floyd and Breonna Taylor really tipped the scales for us, and really the gist of the exhibit is: climate justice is racial justice,” says Christine Abadilla Fogarty, associate director at the Global Museum at San Francisco State University.

As we focus on reducing emissions and switching to green energy, it’s essential that we also make the future more just, and not treat some communities as disposable. Ladonna Williams is Program Director at All Positives Possible, a grassroots organization working to obtain environmental justice for historically disadvantaged and long-term high-risk exposure populations. She shared her personal experience with pollution and chemical exposure living near Pacific Gas and Electric in Daly City and the Phillips 66 refinery in Vallejo.

“We have to address the injustices that have happened historically in order for us to move forward and address these issues. We have to include the racism, the discrimination, the pollution,” Williams says. “Climate change, environmental injustice, environmental racism–they're not separate. There is no line that divides them. They're all encompassing.”

Art, in its many forms, can play a powerful role highlighting these inequities. And it can provide new ways of thinking and viewing ourselves in relationship to the earth. Multimedia artist and musician Sofía Córdova says several of her recent projects were inspired or affected by the climate crisis and exploring the idea of launching us beyond the apocalyptic near future.

“If we can imagine the total destruction of everything we know, every system that binds us, then even if it's after complete collapse, we can start anew. And that became a really exciting prospect,” she said.

Resources From This Episode (5)

Full Transcript

Note: Transcripts are generated using a combination of automated software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the actual audio before quoting it.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. Art, in its many forms, can play a powerful role highlighting inequities:

Christine Abadilla Fogarty: I think George Floyd and Breonna Taylor really tipped the scales for us, and really the gist of the exhibit is: climate justice is racial justice.

Greg Dalton: Art can also provide new ways of thinking and viewing ourselves in relationship to the earth.

Sofía Córdova: If we can imagine the total destruction of everything we know, every system that binds us, then even if it's after complete collapse, we can start anew.

Greg Dalton: As we focus on reducing emissions and switching to green energy, it’s essential that we also make the future more just, and not treat some communities as disposable.

Ladonna Williams: We have to address the injustices that have happened historically in order for us to move forward and address these issues.

Greg Dalton: Activism, Art and Environmental Justice. Up next on Climate One.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One, I’m Greg Dalton.

On this show we often try to shine a light on the vast inequities that exist between those who benefit from extracting and burning fossil fuels and those who suffer its impacts first and worst. Art offers a lens for exploring energy and mineral extraction and challenging audiences’ worldviews in ways that can be subtle and disturbing.

With that in mind, we hosted a discussion with some of the people behind San Francisco State University’s recent exhibition, Clearly Polluted: The Fight for Environmental Justice in the Bay Area. The exhibit investigates environmental racism and its ongoing, disproportionate impact on Black, Indigenous, and people of color. It was co-curated with community advisors and advocates who share their lived experiences and ongoing efforts for climate and social justice.

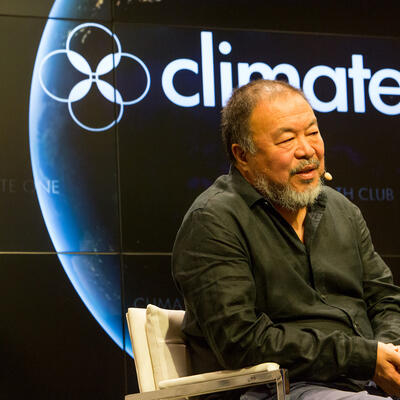

Christine Abadilla Fogarty is Associate Director at the Global Museum at San Francisco State University. Ladonna Williams is Program Director at All Positives Possible, a grassroots organization working to obtain environmental justice for historically disadvantaged people. Doug Harris is a former professional basketball player and now documentary filmmaker. They joined me for a conversation with a live audience at the Commonwealth Club of California, to discuss the role of art and media in surfacing climate and environmental justice impacts. Ladonna Williams began by sharing her personal story.

Ladonna Williams: I started as a teen mother and my first apartment away from home. And I lived there for 10 years, had my first two children there. And it was a beautiful housing area. They didn't call them projects, the typical low income projects. They were townhomes. And so, and in back of it was also a huge playground for the kids. And the school kids would come there for their P.E. So we had no idea that we were actually living on a toxic dump, but we should have known because there was no fence line. And I was actually in an apartment away from PG&E. We saw burnings that at one point we thought were beautiful at night cause it lit up. And we also had a farm that was on the other side. And in the beginning the animals looked okay. But as time went on, they began to take on this strange look and my children would bring home two-headed frogs, literally, because it was a stream that ran between the property and also PG&E. And so again, not putting it together, 10 years almost to the date when I moved there passed, I get a phone call that men in bubble suits appeared at Midway Village. This is in Daly City, a couple of blocks down from the Cow Palace, and the phone call was, look like spacemen are out here. These men are all covered up. Come to find out, they were doing a cleanup without notifying the residents. They called it a beautification, which is why I use the term environmental injustice can appear to be an art of illusion. It is an art of illusion. Some people say, oh, it just appears that way. No, it absolutely is because most of us were fooled into believing we were in safe, sanitary, clean housing only to discover we lived on top of 365 plus carcinogens that now that we look back, we recognize were tied into the many trips that we made to the doctor. My daughter, unfortunately, was born with cerebral palsy. We played in the area as a kid, and I just thought it was unique to me. But again, reflecting back, I recognized, wait a minute. We were hearing the ambulance regularly. People from the community, residents were being taken to the hospital. But again, this is 10 years reflection of living on this, this toxic dump that we discovered was toxic, we thought, well, we've gotta tell the agencies, we've gotta tell the authorities they don't know what we're, what we're discovering, only to find out with the many documents, they've known for 50, 60 years and counting that this site was contaminated. So we were the last to know.

Greg Dalton: That's quite powerful. And not unique to San Francisco or California. Those sorts of stories happen in many places, unfortunately. Christine, Daly City is adjacent to the western part of San Francisco, where San Francisco State is located. That area, I learned recently, was zoned for single family for a particular reason. What did you learn about the history of the university's neighborhood and researching the Clearly Polluted exhibition?

Christine Abadilla Fogarty: Yeah, and our research found that red lining happened and it's something that's happened over time. It affects not just San Francisco, but everywhere and that San Francisco State is right next to Daly City, which was also developed on that land. So just that realization that we are on toxic land was really kind of eye-opening and having to deal with that. So the exhibit actually explores these kinds of situations where history has impacted the land and how we live and how it affects the people who live in these neighborhoods.

Greg Dalton: And just to kind of unpack it and spell it out, that part of San Francisco was zoned single-family housing to keep out people of color. Probably particularly Black people in that part. And that's, again, that is not unique to San Francisco. Doug, after playing professional basketball, you started making documentary films. One of your films, North Richmond, Past, Present, and Future, chronicles the story of that city near San Francisco Bay that is home to the Chevron Refinery, one of the single largest sources of pollution in California. The refinery has operated for more than a hundred years. Tell us about the restrictive covenants that dictated who could live where and how that relates to the city of Richmond, California today.

Doug Harris: Well, when Black people came, migrated West from different parts of the south and other parts of the country, they primarily came here to the Bay Area to work in the shipyards. And so those that lived in Richmond, they were relegated to live in one of two areas. One, the housing projects and two, the unincorporated community of North Richmond, that neighbors, which was then Standard Oil, but today is Chevron. And so the Black community, that was pretty much the hub of the Black community in West Contra Costa County.

And they were relegated to live there if they wanted to own their own property and build homes. And, and so there's been a long history of unhealthiness for those residents. And I worked in North Richmond during the nineties for like five, six years. And I noticed that a lot of the young kids had asthma and a lot of their grandparents, you know, they were, it was cancer riddled the whole community. And this was before I started doing documentaries, but when I started doing this four-part documentary series about the history of North Richmond, I started to understand what was really going on in relation to the Chevron refinery and the effects that not only Chevron, but General Chemical had on that community. And so doing documentary films has really opened my eyes as to the real serious issues of environmental justice. Cause I'm a former ball player. What do we know about environmental justice? But, but it has really opened up my eyes and it's made me want to explore and, and even talk about it because it's through producing documentaries that it gives me a chance to educate people about what's really going on.

Greg Dalton: Christine, you live in Oakland, a city divided by freeways that have different rules for diesel trucks, which was new to me recently. For 70 years, heavy trucks have been banned on the 580 freeway, which goes through wealthier neighborhoods and heavy, mainly diesel-powered trucks are allowed on the 880 freeway, which runs through lower income communities of color. So what's been your emotional journey learning about these things in your own community and were you impacted in ways you didn't anticipate?

Christine Abadilla Fogarty: Well, we live in an area called Maxwell Park, which in the course of our research for our exhibit was completely tangential. Maxwell Park used to be like an exclusive community for white people and then over time, as white flight went out to the suburbs, people of color and Black folks would come in and move into those properties because the property became affordable to buy. But then over time, you know, it's the systemic disinvestment as the wealth left the city. And that part where we live, all the infrastructure, all the conveniences, are not easy to get to, right? So you look down our street and you see potholes. When it rains, you see the drain, the water does flow against the drains, but they don't really go down into sewers. They just are on the street and contributing to the pothole problem. You're almost in a food desert. There's not really very many corner shops that you could go to to just get fresh fruit or vegetables. You have to drive like five miles away to get to it. And you can hear the freeway noise and the air pollution that you get too. So, it's kind of weird to live in this place. I love the neighborhood and a lot of young families are moving back in and really building up the neighborhood, but I think the realization is like, wow, am I part of this problem? You know, is this the gentrification that's happening that we moved here, like what ten or so years ago? Because it was affordable to us. But then you see, you know, folks coming out of San Francisco into these affordable places, and then you just realize, wow, am I also part of this problem?

Greg Dalton: Sounds like this was a real eye-opening experience for you. LaDonna, you're program director of All Positives Possible, a grassroots community-based organization working to obtain environmental justice for historically disadvantaged and long-term high-risk exposure populations. How are you trying to address the injustice as we've been talking about and portrayed through the art we've seen here? And what role does art play in your work?

Ladonna Williams: Art plays an important role. For instance, the storytelling and story sharing is what we're doing here, and that's an art. And she touched me when she talks about Oakland because as they transition, as they say, into these neighborhoods right around Oakland, what do you see? Blue roofs. You know what blue roofs are? The tarps that black people use to live under now, cause they no longer have wood homes or you know, homes made of sturdy cement. They're literally living on the street and they're an ignored population. We talk about environmental justice. We came up with All Positives Possible because what our communities are dealing with, you really go into this deep depression and we had to figure out how do we reverse that? You know, you gotta put it in your mind first to push past that, that fear that first of all, I've come from a toxic dump. Living on it. Didn't know it. Moved to Vallejo, only to find out that we're still being hit by so many sources of pollution. The refinery Phillips 66, New Start industries that blew up on us in 2019. The ships, huge tankers that come through that spill toxins into the water, and then you turn on your water in any given day, it's brown. And the authorities tell you, oh, don't worry about it, just drink it. But just cautiously drink it. Okay, but bring a bottle to a meeting and ask them to drink it, and you're gonna get a whole different reaction. So what we've taken on is, the actual lived experiences of the everyday folks who are historically disadvantaged, high risk, long term that live along the shorelines, whether it's Bayshore. I was born and raised in San Francisco. My dad and family fished as we lived off the land. You come through Richmond along the shoreline, same thing. Rodeo, Vallejo, we as Black folks and on that front line, literally live off the land, but we're forced to live off of polluted land. And so when we come in these spaces and we hear environmental justice for all, or we're in it, you know, we're all in this together. Or even when we give these presentations, you hear the term Black and brown. Black and, Black and. They won't even focus on the fact that Black folks, by and large, has systemically been placed in these to, on these toxic dumps that folks all know about. And then we just go on with, life is normal and it's not. And we won't stop and address specifically the injustices and the racism that has happened to black folks without adding other populations in, It's not us against them. We really are to share this earth, but you cannot continue this injustice against Black folks and we go on and act like it doesn't exist and we can take it from here and move forward. We can't move forward until we stop and address what has happened to us. And that is the redlining, the systemic racism that have allowed agencies and our government, even our president right now, if you mention Black specific stuff, he's gonna move on to the next subject. Even some of the Black leaders will do that. I've called several Black leaders to say, Hey, what about this reparations bill? They don't want to hear it. But if you say immigration, oh yeah. We have resources for that. We have to address the injustices that have happened historically in order for us to move forward and address these issues. That is the term All Positives Possible, but we have to include the racism, the discrimination, the pollution. Like we have these huge injustices that go on under the term of climate change and for us, climate change, environmental injustice, environmental racism. They're not separate. There is no line that divides them. They're all encompassing.

Greg Dalton: Doug, your thoughts on that and, and you know, and what role you think that art plays in con, you know, addressing the storytelling and other forms of art and addressing the injustices that LaDonna just so eloquently laid out.

Doug Harris: Well, I think it's important for people to be properly educated in learning what took place 50 years ago that put us in that position. And I really, uh, admire the work that you doing LaDonna in terms of addressing those things. And that's what I try to do myself in terms of being able to educate people through history, through the work that I do in filmmaking. People say that it's an art, and yeah, it's an art, but I look at it more as educating people. It's a combination of art, education and activism.

Greg Dalton: And one really powerful thing happening there, of course, at the intersection of education of the national myth or story we tell ourselves is the 1619 project, which is trying to say, now let's start in 1619, not 1776. LaDonna, Doug spoke about the need for education. Art and music are often the first to get cut when school budgets shrink. We know that story in California, thanks to Prop 13 and others. Yet California recently passed another ballot initiative that will increase arts funding in K through 12 schools by up to a billion dollars a year. Growing up, you went to field trips to museums. Your kids, not so much. So how did those visits enrich your life and inform who you are today and how do you think museums can amplify the stories we're talking about?

Ladonna Williams: Well, fortunately I grew up in San Francisco, so you know, we went to the Cow Palace and experienced a rodeo. We went to the Palace of Fine Arts. We went to the museums and we even took field trips, uh, Union Square, where the teacher would take us into these art stores where you would see a painting. And back then, I'm not gonna tell y'all how old, I am. But you seen a little ticket and we were trying to read it and we go, oh, that's $20 with a bunch of zeros. And the teacher says, no, that's $20,000 for a painting. You know? So we got that rich experience. But I have six children. And you fast forward now, and most of the schools, at least the schools in our areas, do not take the kids on these field trips anymore. And reflecting back on that, that is such a missed opportunity to enrich our kids' lives. I've had to do it on my own and on my own dime, but that's an investment in my children. We should all do that.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. Let’s return to my conversation with three guests behind San Francisco State University’s latest exhibition, Clearly Polluted: The Fight for Environmental Justice in the Bay Area. We’re talking about how art can help elevate and educate people about environmental justice. Christine Abadilla Fogarty is Associate Director at the Global Museum at San Francisco State University. Doug Harris is a documentary filmmaker. And Ladonna Williams is Program Director at the grassroots environmental justice organization All Positives Possible. She spoke about the need for having conversations that are often uncomfortable.

Ladonna Williams: They call 'em difficult conversations. They're not difficult to me because if I can hold paperwork and see my family. On both sides. I can tell you the name of two of the slave owners that held rights to my family, Eliza Wright, which is a white woman, and Bill Smith, who was a Cherokee. They both owned slaves on both ends of my family's lineage. And I'm not supposed to speak of that in these venues because they say it's polarizing or it, it creates this, you know, uncomfortableness. Well, damn it be uncomfortable. Because if I can trace my family's history back a hundred years and see that they've been enslaved and they've went through this traumatic life to try and make a better life for the generations to come, who am I not to grab that and take that and turn it into an art of storytelling, because that's what my parents did for me. They told the stories before and, and mind you, these documents that I've gotten has only been within the last two years, and that's thanks to social media and the advancement of technology, I can now trace my family's history. Previous to that, I only knew about it through the storytelling, which is that art and education that my parents talked about. And I used to say, oh my God, I can't stand old people and these stories, and now I'm the old people in these stories, you know? But that was how they connected us to who we are and how we need to move forward. If we're talking about justice for all, which I absolutely believe. An injustice to anyone is an injustice to all of us, but you cannot ignore the injustice and the contribution that Black people made to build this country for free. And then we move forward in these spaces, like even this beautiful, uh, uh, technology. This building is awesome. It's beautiful. You guys got all the amenities, but you go a few blocks down the street and we're looking at Hunter's Point and there's technically Black homeless people put in these trailer homes. And the sickest part about it is this black leadership that made the decision to do it. So, I bring it in there. Sorry to get you off script, but if I'm given a platform, it is my calling to share this story and help educate through storytelling, through art, through documentary, through interchanging that I am obligated to share this anytime I get an opportunity.

Greg Dalton: Thank you for sharing. Christine, why don't you tell us about Clearly Polluted, what, how it came about and what you're trying to achieve with this?

Christine Abadilla Fogarty: Yeah. So Clearly Polluted was our pandemic project. It took two years to do, and it was inspired by, uh, you know, all of the social justice demonstrations that were happening in 2020. I think George Floyd and Breonna Taylor really tipped the scales for us, and really the gist of the exhibit is, climate justice is racial justice. So we wanted to explore that. And it's such a universal topic we came up with an outline that just identified the themes that we wanted to explore, so themes of displacement, environmental impacts, what pollutants, what, what it looks like visibly, what, what was that pollution? And then the resilience, because we wanted not to, for it to be so doom and gloom, we wanted it to end with some hope and to kind of mobilize our young folks to like, listen, you can do things, you can have a small impact by just, you know, bringing a usable bag to the grocery store, or, you know, connecting with the Black Unity Center on campus and seeing what food banks and stuff that you could contribute to. So, part of the story of it, we knew we had this basic outline and the story was fleshed out. When we connected to Doug and LaDonna and seven other community participants, we knew that their stories would flesh out this outline. And in fact, their stories became the exhibit. So if you were to go to the exhibit, which is available online. We don't use objects, we use photographs. We feature the videos in particular and we pulled quotes, really impactful quotes from, um, the exhibit to become the objects to become the story. And that's what we want the Global Museum to be is not so much, because museums have a colonial history, right? They have a long ways to go to combat that. But for us as a university museum, we wanna be able to use our platform to combat that, to share the storytelling with the communities that are affected by the objects that we exhibit, by the stories we wanna communicate. And really just become a facilitator and be that platform.

Greg Dalton: Let's talk about that colonial history of museums, cause you know, museums are very tied in with wealthy people that have extracted a lot of wealth, probably connected to the types of, sources of pollution we've been talking about here. So, and some museums have, uh, gone through a journey of reflecting on their role. You know, Teddy Roosevelt's statue was removed from the Museum of Natural History in, in New York and others. So how has your view of museums changed going through this project on environmental racism?

Christine Abadilla Fogarty: Yeah, I still kind of grapple with it. It's like, I love museums. I think you learn so much about the world through the objects that they display. And museum studies, I think is positioned to educate our students to be change agents, right? To think outside of that Western, Eurocentric box and share and facilitate stories with the communities involved to really privilege the makers and the source communities whose stories are latent in these objects. And to also bring in artists who I think are so important to, you know, they're the pulse of life now, right? They're the ones who are actually living it. And to bring all this together, I think is the future for museums is to be able to step aside and maybe share and have artists, community members just share their stories from there instead of scholars interpreting what they're hearing.

Greg Dalton: Less kind of elitist. Yeah. LaDonna, California has a suite of climate laws and policies that direct funding to underserved communities as part of its move from fossil fuel to cleaner energy. There's cap and trade funds and that's come about because just legislation and pressure from environmental justice activists like yourself. The Biden administration has elevated the role of climate justice and its policies and appointments, has been saying they're more active in that area. What kind of funding are your peers and black led organizations seeing and what kind of funding are you seeing? Is there more flow money flowing to the places that need it?

Ladonna Williams: Well, they say it is, and on the surface it appears to be, but when you compare the average grant for a Black-led organization working on Black specific issues. And I focus on that because the historically disadvantaged, highest risk, longest term exposed population is still Black folks. Yet when you look at the funding pool, the funding averages $2,500 to say $5,000 for a Black group that is working on just too many issues to count. And then you look at these NGOs, these non-governmental organizations who come to us in the form of listening sessions and, Hey, let's have these, you know, workshops and the whole time they're taking down your intellectual properties and your experiences.

Greg Dalton: Another form of extraction.

Ladonna Williams: Absolutely. And then they go and they write because they have the, the grant writers, they have the to, you know, engage and travel around. They come up with a million dollar grant. So yeah, you're giving us more grants now than you've given us before, which was very minimal. But when you look at the amount that we are getting, it is giving us just enough to fail and it gives them enough to succeed. And many times you have residents that have been in a community that have never moved out of their community and have taken on these issues and tried to get funding and could not get funding. And then they have new folks that come in and take over the community's issues and voices, and they literally walk them through the process of getting funding through whatever their programs are, where they want to hear new voices and, and new approaches. We don't have a problem with that. We welcome growth, but you can't come into my hood and overlook me and my issues, and that's what happens. And so when we hear Biden's, new proposals, J 40, justice 40, EJ 40 whatever, and Gavin Newsom. And you know, at one point they were talking about this surplus and how much money was going towards EJ and what have you. Our communities aren't seeing it. We still have the major potholes. We still have, you know polluted water coming through our pipes and living on top of a toxic dump that has not received proper cleanup. So on the surface it appears, oh yeah, you know, we've got all this money coming through, but we have yet to see this fair distribution. We hear the racial equity, we hear, oh yeah, we're taking on these financial equitable projects where we're looking. We ain't acting on it. We're looking at, you know, different approaches, but in the meantime, they're still using that same funding structure where we usually have to go to a larger white organization to beg them for funding or inclusion. And then we have to jump through these hoops and, and even just the process with applying for a grant from the federal, from EPA’s environmental justice program, you gotta go through grants.gov and ID me. And, and then you gotta go through their portal and then you gotta figure out, looking at this, you know, a hundred page monster of a proposal. By that time you starving to death, your lights is being cut off, your stomach is growling. You need some support right then, while you're also trying to figure out, you know, what are these cracks in, in, in my community? Why is my pipes not working? Why does my toilet not flush properly? By the way, what is this smell? You hear from your neighbors, folks are literally passing out only to discover later on we're being exposed by vapor intrusion. Vapor intrusion. Like we're normal residents. We are forced to become these scientists and these, these, you know, specialists in these fields that we have no idea about until our bodies start to tell us, you better learn if you wanna survive, you better figure out, you know, what a P N A is, or benzene or all these other things that are coming through our air and soil and water. You know, these are all elements in the earth that is hitting us. That should not be because community is being exposed by all of these polluting sources that's been licensed and permitted to come into our communities. They tell us, well, you know, maybe, you know, consider moving. Well, how about consider not putting polluting industry in our communities?

Sofía Córdova: I was really young. I, I couldn't have, I maybe was three, but I remember we lived on, I think it was the 11th floor of a building in Miramar. So Miramar, as the name suggests, overlooks the sea. So the winds were very, very felt. And it was a community that had a lot of elders. And I remember all of the folks from our floor just sort of organically started kind of coming to our apartment cause my parents were young parents. I was a little kid. So we were sort of the best equipped to kind of host everybody. And I remember two things. One, that it was extremely... I don't wanna say scary, but there is this air of mystery, when we're visited by these sort of events, there is such a way they push us out of what we know in such a way that it actually starts to operate really differently on our modes of thinking and on our modes of being.

And even at that young age, I remember the sort of tension in the air from all of these people having to, in a sense, be relocated temporarily and come to our place. We, of course, immediately lost power. So I remember everybody also kind of gathering what they had and all of these little gas stoves kind of assembled altogether. And I remember we made tortilla espanola and everybody ate. And that's the other part that I remember really vividly that in the middle of this tension, and this would be fear and suspense, really, there was also this incredible network of care. Appeared immediately and we were able to sort of feed one another. And I remember that feeling like an anchor and what was otherwise very unsteady, uh, ground really.

Ariana Brocious: So you started introducing climate themes into your work in 2012, and can you tell us about the first piece where you did.

Sofía Córdova: Yeah. So that was a series called Echoes of a Tumbling Throne/Holas a fines de los tiempos. I wanted to expand how marginalization happens through colonial vehicles and empire, and so I started working, thinking about work that would encompass all manner of colonized subjects, Black and brown subjects, Indigenous subjects, queer and trans bodies in the United States, because that's where I was living at the time. Always internationalist, I should add. And I, as I was sort of having that seed of a thought, I was also noticing that in 2012 there was this sort of great crackling in the air where, in the western world particularly, there was an obsession with the Mayan prediction of the end of days. And I just thought there was something tragic and comic about ascribing the ability to kind of foresee the end of days to a people that these very same European Western cultures say can't have possibly built their own pyramids because those are architectural marvels. And to me there's something really scary, but also worth challenging about that very kind of racialized view of the Indigenous other, where there is like a conduit to spirit, but no conduit to intellect. Which is of course how those same people, those same European peoples can justify colonial violence and enslavement, and all of the other ills that followed. So with those two sort of grains in my mind, I started thinking about the future and I realized that I wasn't really interested in the kind of quote unquote apocalypse or this end of days moment, but that in thinking about the liberation of colonized Black, brown, Indigenous, queer, trans bodies, I was really thinking that the future was an incredible place to posit us because if we can imagine the total destruction of everything we know, every system that binds us, then even if it's after complete collapse, we can start anew, and that became a really exciting prospect. So I started working with other performers and placing these performers in front of a green screen and then creating these sort of, what I call kind of digitally corrupted ecologies, right? Where like the natural landscape becomes really glitchy and really crunchy. And at first they were just sort of these experiments and like people in place. I'm a research based artist, so as I sort of sat with what the conditions could be that led us there without again, being too apocalyptic and thinking of a single event, climate change kind of became the natural culprit, the natural kind of antagonist just because of where we seem to be headed. And as I sort of lived with that longer, the research started kind of infecting the work. And so in some of them you see bodies in front of, again, very digitally corrupted footage taken by tourists of icebergs collapsing on these sort of like Arctic tours. So climate change and its causes and effects became really important sort of aesthetic and conceptual fodder. And then as I went deeper and deeper and deeper into that mode of thinking, I started also thinking about what are the links? With colonialism, with capitalism, with Empire, and the subsequent realities that we're facing right now due to climate change, right. How does the extraction of resources and bodies out of the Caribbean, out of West Africa, out of South America, um, within the Southern United States itself, how did those conditions accelerate climate? And in turn, as we're living it now, put in precarity, the very populations that have been harmed throughout.

Ariana Brocious: That's so interesting to hear you reference 2012 and thinking about the Mayan calendar and the predictions. I remember that. And to me, I think of 2012 and I immediately think of the drought. It was like a year of really intense drought in the Western US and there was a lot of concern around, you know, is this a tipping point? Is this a place where we're gonna to finally take stock of water shortage in some of these things? Because, you know, it was really kind of getting in some places dire.

Sofía Córdova: Well, something about that really quickly. It's funny how as a species we need these things narrativized, right? Like a drought conjures up an image and then maybe we can be led to action. But then the moment it's, it sort of pushes away, we kind of go right back to the way we've been behaving. And it's just, I'm, I'm really fascinated by that. I think it's really interesting and it, and it speaks so much to how we tell stories and how we need to tell stories in order to actually take things on. And I think in a way we haven't quite found how to tell the climate story in a way that we ourselves believe it

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, it's a work in progress. So in your mind, what's the role of activism in art and art in activism?

Sofía Córdova: Yeah, that's always a tricky question. I had a friend beautifully say it once where she said that art and activism are actually different medicine. I think that the two can certainly cross. And I think that, you know, when I think of say the protest of 2019 in Puerto Rico, how they were protests, they were bodies in the streets demanding change, but they were also musical and they were also, in a sense, they were a performance, right? Each new act unfurled with like a new kind of aesthetic and, and sensorial experience. So I certainly think that in that flow of the stream, art has a lot to offer activism. On the other end, I worry in a sense, when activism comes to visit the art because, or the art world, because I'm really quite cynical about the art world. The architects of the art world are actually quite linked to the people that create the problems that we're all struggling with in the world, whether it's weapons manufacturing or being oil barons themselves. So I am always, I don't think that it's impossible, and I think some artists have certainly done it with like great effect and elegance. But I'm always a little wary about fitting in the practices of activism in the art world as we know it now, just because sometimes I worry that that's a mode of co-optation, um, by these institutions in a way that lets them get away with what they were already doing.

Ariana Brocious: We had an interesting conversation on Climate One with Shepard Fairey a couple years ago that also referenced some of those ideas and would be interesting for listeners to check out. You've said that we're living in a time of ambiguity and that that ambiguity can open us up to a space of radical imagination, which might be the only thing that will get us through this time. So how can art inspire that radical imagination?

Sofía Córdova: I'm very invested in this idea of ambiguity because I think it provides us with a sense of slippage. It lets us look at what is, and quite distinctly, I think in our specific moment, see the cracks through which it all is starting to crumble and it all starts to fall apart. And not to always look at it on the sense of destruction. What can be, what can we fill that in with? And that's the place that I sort of want to coax this imaginatory kind of experience out of folks. And I think that that's what my work ultimately wants to do. And this is a good segue from the activism question because rather than saying we all need to find modes to be with activism, which I think is really important for all of us to do. I think the practice is important and it's daily. I think the step beyond that, both within art and activism, because I think it's also a political question, is to imagine something that is completely beyond anything that has been imagined because the problems of our time require those types of solutions. I think that the powers that be, whether it's capitalism or the way that it has fed into kind of the way that educational becomes an indoctrination tool towards capitalism and sort of the acceptance of US empire particularly, I think that those machinations have very elegantly made us think that imagination is a child's thing, that it's for play. And I would posit that rather play and thinking in these “childlike ways” are actually things that we've evolved to carry with us as a mode of thinking through our problems. And I think that, it brings us another point of connection with systems and patterns within the natural world that we are part of. You know, we have such a fundamental understanding of ourselves as separate from all of these systems and patterns where in fact we are part of it. And I think that imagination and play puts us back into that sort of rhythm. And once we allow ourselves to be in that slip stream, we hopefully can give ourselves, not just permission, but agency to imagine something different because it's up to us. Radical imagination can be and should be really beautiful collective work because I think that once we're all in this space where we have given ourselves this agency to take control of what is possible in our minds, right? Essentially decolonize our own minds. And if we start doing this in congress, then what can start to happen? Every new strange idea meeting, another new strange idea can actually start to create sinew that becomes actionable.

Capitalism is a really elegant thing that someone imagined and then made and, and then made real, you know, many somebodies, but still. It all, you know, something that I always come back to with this conversation is brilliant Ursula K. LeGuin, when she writes in her non-fiction work, right, like the Divine Right of Kings used to be something that was considered permanent and eternal and it's been done away with, right? So it's possible. It really is.

Ariana Brocious: Another theme that comes through in your work is wanting to move us away from an anthropocentric view, right? And you have a piece titled The Gentle Voice that Talks to You Won't Talk Forever, that was inspired by a thousand year old cherry blossom tree that lives outside the Fukushima spill site. So before we get into talking about the piece itself, can you describe it for our radio and podcast?

Sofía Córdova: Yeah, so that work is actually an installation. So when you walk in, it's a room where the lights have been gelled, sort of softly pink, and the first thing you encounter is a dove that has been dyed, like a kind of baby pink, standing on a Corinthian column. To the right of that, there is a flickering video that is projected in bright light, so it looks very washed out of cherry blossoms with the sky having been digitally changed to various different colors. And along the way on the floor you see coral, that's this kind of same pinkish hue and you see quartz that's been dyed this kind of pinkish hue and a curtain that sort of cascades on the left side. In it, there's these flowers that are playing this sort of audio track that kind of borrows from the Ace of Bass song, and that's where the refrain comes, the gentle voice that talks to you won't talk forever. Where I'm sort of appropriating this pop moment and this pop motif to really, hopefully right, create this sort of sense of augury in the song, create a sense of warning for our species. That these warnings that are coming very discreet, but discreetly and strongly from the natural world will stop coming one day and we'll just be in it.

Ariana Brocious: And give us a sense of why this, you know, you explained the inspiration came from this cherry blossom tree, but maybe break that down. What about the tree inspired you and, and how that piece does this work, of trying to feature non-human centered art or experiences?

Sofía Córdova: So I was in my research sort of thinking a lot about actually thinking a lot about nuclear nuclear test sites out in the US American desert. And just thinking about kind of, again, nuclear kind of spills and what resistance the zoological and biological world had created against it. And I found that there was this cherry blossom tree that is millennia old. Huge. Beautiful. About 20 to 30 kilometers outside of the Fukushima spill site. And this cherry blossom had been the site of pilgrimage for people for thousands of years, and there is a really beautiful haiku written in 1884, I believe that was written for it, and that's included in the work. That's sort of the only kind of presence of the human hand other than the song in that installation. And when I found that, I was really fascinated by the fact that there was all of this sort of touristic infrastructure that had been built around it. So it's a huge old tree. So over the years, it had been pruned and sort of helped to grow in certain ways and it had these sort of crutches, if you will, that were sort of holding it up in certain areas. And over the short period of time since the spill, and perhaps because of the spill, a lot of that infrastructure started to decay or break down or go away. We know this because there was drone footage that was produced from that tree around the time it was expected to blossom. The other thing that that footage revealed, and this is where the inspiration comes from, is that the tree was blooming beautifully right after the spill. It didn't even take like a year off. It just had this beautiful bloom. And to me, there was something really poignant and beautiful about this organism blooming more beautifully than ever without the eyes that had traveled to see it for hundreds if not thousands of years. And to me, there was something really special about that experience, both as it points to a mode of resilience that's built into natural systems on our planet, but also as a negation of the view from a human perspective. So it inspired me to think about climate, from a non anthropocentric position. What if we start thinking of climate change as a tree or a bird, or a stone or a coral reef? If we decentralize our own perspective as the foundational kind of primary perspective, what are we capable of doing? How are we capable of understanding the climate crisis? And I think that we would actually be far more adept at understanding it if we could extend that grace to other living forms on our planet.

Ariana Brocious: So you've spoken about how your own increasing awareness of the climate crisis has changed you as an artist. How has it changed you as a person?

Sofía Córdova: That's a very heavy question. I think there was a moment I think that maybe sums it up in 2015, so a long time ago now when I was working on echoes of a tumbling throne, and again, when I started that work, I had this idea that I was sidestepping the idea of apocalypse itself. I didn't think about a certain event. I wanted to think about what was possible on the other end, but as I was living with the research and I was sitting in the contemporary moment, Sandra Bland had just been murdered by the police. There was no other way to describe it. I was just in despair. These facts and figures, the rising tides, the melting ice caps, all of that became unbearable. And so what I ended up putting, how I ended up putting that in the work is that that might be the beginning of where I start to kind of play with and coax out this idea of ambiguity. So I made the three characters that sort of embody that work be these sort of apparitions. I sort of imagined them as tecnorishas, right. So these sort of spiritual apparitions that are illegible in a sense, and they're saying something that feels really important and laden with meaning. But we are in a position where it's difficult to kind of unspool that. And that might seem, in a sense, despairing to the audience as well. But that's not necessarily an experience that I shy away from because I'm not interested in creating a situation or a narrative where we are exclusively given out rosy images of hope. No, our situation is dire. And so I think that was kind of maybe a way that I could metabolize it right, like live through the research myself while also infecting the work with it. And I use that word kind of intentionally because I think a lot about contamination and in a sense, this idea of hope and radical imagination also is maybe linked to this idea of contamination, right? Sort of spreading something from the work out and thinking about that as a condition. is already evidenced in how, again, colonialism and capitalism have affected our lives, and these things are not, we can't undo them. They are already part of it. So the work wants to think through it, but the work also wants the audience to, to think through it.And I think that's maybe how I've dealt with it. Often, it's very despairing. Luckily, when I'm either here in Puerto Rico or in Northern California, I am very close to natural landscapes that cleanse me and remind me of geological time and that maybe, maybe this story isn't the most important story told on earth. Um, but that's very heady.

Ariana Brocious: I think that that connection with the natural world does that for many of us. Right. Kind of grounds us and centers us back, reminding us of our place.

Sofía Córdova: Yeah, looking at an old rock really grounds me.

Ariana Brocious: Sophia Cordova is a multimedia artist and musician. Thank you so much, Sophia, for joining us on Climate One.

Sofía Córdova: Thanks for having me.

Greg Dalton: Find a link to Sofía Córdova’s work on our website. On this Climate One... We’ve been talking about activism, art and environmental justice.

Climate One’s empowering conversations connect all aspects of the climate emergency. To hear more, subscribe wherever you get your pods. Talking about climate can be hard-- AND it’s critical to address the transitions we need to make in all parts of society. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. You can do it right now on your device. You can also help by sending a link to this episode to a friend. By sharing you can help people have their own deeper climate conversations.

Brad Marshland is our senior producer; Our managing director is Jenny Park. Our producers and audio editors are Ariana Brocious and Austin Colón. Megan Biscieglia is our production manager, who co-produced this episode. Our team also includes Sara-Katherine Coxon and Wency Shaida. Our theme music was composed by George Young (and arranged by Matt Willcox). Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.