Shepard Fairey, Mystic and the Power of Art

Guests

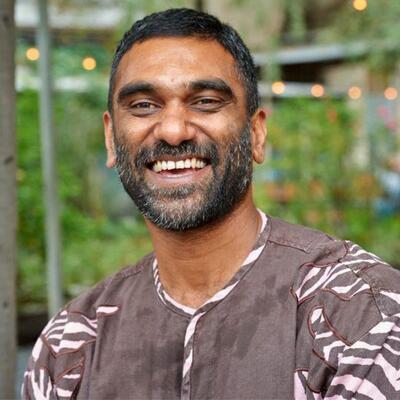

Shepard Fairey

Mystic

Summary

Shepard Fairey is best known for creating the iconic Barack Obama “Hope” portrait during the 2008 presidential election. Fairey’s work is now included in the collections of the Smithsonian, the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, the Modern Museum of Art in New York and many others. Fairey says as a young man, he was drawn to counterculture.

“Punk rock and skateboarding showed me a culture that was about ignoring what the mainstream was doing, using creativity to build your own scene and it made it cool to have an honest and unvarnished voice,” he says.

Much of his art and activism has focused on the environment and climate change. He says he uses dark humor and human protagonists to draw people into his pieces.

“I'm taking a lot of different approaches but rarely is it just ‘Save the Whales,’” he says. “I do want the whales to be saved, but … it's more seducing people with something that maybe will get them to reflect upon it and make their own choice rather than feeling like they're being judged.”

Fairey says it can be difficult to walk the line between motivating people and discouraging them with the full picture of what’s at stake with the climate crisis.

“It's important that people understand the severity of the issue, but it's also important that they don't feel paralyzed because it's too overwhelming. So, I'm always trying to see how I can get the balance right in my communications with both the text and the imagery I'm using.”

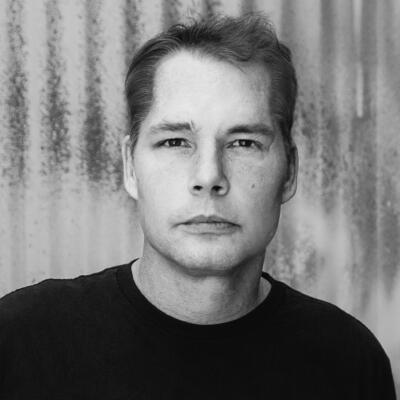

For Grammy-nominated hip hop artist Mystic, art has allowed her to build a platform to advocate for social justice and connect with people in power.

“Art allows people to tune in, right? I think sometimes when we’re enjoying ourselves or engaging with art, some of our defenses come down,” she says.

Humor can also be an important tool and form of release, she says, especially when talking about difficult subjects like climate change. Mystic is also a community educator, and currently the Program Manager for Hip Hop Caucus’ Think 100% FILMS division, which produces films that center on climate justice. Their first film is a comedy special called “Ain’t Your Mama’s Heat Wave.”

“How do you make the climate crisis funny, right? Something that's not funny at all. How can we talk about it in ways that open up where people can think about it in different ways and we can start to have conversation... And so, Ain't Your Mama’s Heat Wave is really about joy as part of resistance.”

But Mystic says that doesn’t mean forgetting the need to respond to the crisis at our doorsteps, especially in minority and low-income communities.

“This is a call, this is an emergency that’s happening, and we need to understand that the climate crisis is not just in other places in the world, but it's happening in communities, in our nation, in Black communities.”

Related Links:

Ain’t Your Mama’s Heat Wave Trailer

Hip Hop Caucus

Shepard Fairey Art

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. How can the arts inspire and advance the climate conversation?

Mystic: Art allows people to tune in, right. I think sometimes when we’re enjoying ourselves or engaging with art, some of our defenses come down. In particular for me as a music artist, music is a universal language, right.

Greg Dalton: But communicating about the climate crisis can be tough, even through a song, mural, or poster:

Shepard Fairey: It's important that people understand the severity of the issue, but it's also important that they don't feel paralyzed because it's too overwhelming. So, I'm always trying to see how I can get the balance right.

Greg Dalton: The power of art in the climate emergency. Up next on Climate One.

Greg Dalton: How can art help us connect with the reality of climate change in a different way than charts or data? Climate One’s empowering conversations connect all aspects of the climate emergency. I’m Greg Dalton.

Shepard Fairey is best known for his Barack Obama hope poster during the 2008 presidential election. His work is now included in the collections of the Smithsonian, the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, the Modern Museum of Art in New York and many others. Fairey says he was a rebellious youth. I asked him what punk rock taught him about art.

Shepard Fairey: Well, growing up in Charleston, South Carolina which is a very beautiful place but not a progressive place. I was only exposed for a long time to art that was decorative or was reinforcing a lot of the clichés of the region. My dad told me when I was a kid, you know if you're really successful you might one day paint the duck stamp. And that didn't connect me that much then it actually probably connects to me more now because of my understanding of ecosystems, you know, the ducks place and things, you know, is more meaningful to me now. But punk rock and skateboarding showed me a culture that was about ignoring what the mainstream was doing using creativity to build your own scene and it made it cool to have an honest and unvarnished voice. And what I realized was all these tools of empowerment because punk rock was not supported by the dominant framework, like making stencils and homemade T-shirts and stickers and flyers for promotion. This is all incredibly empowering and so, you know, that coupled with the messages from a lot of the bands I liked in punk rock whether it was The Clash or the Dead Kennedys, Black Flag all of that plus I did get into Bob Marley also who had a lot of great political messages. This made me think about how creativity is not just to make artwork to match the couch but how you can do something culturally with it.

Greg Dalton: To have purpose more than just pleasing to the eye. When you were in college you saw an art piece depicting the globe with a mask around it. How did that shape your environmental awareness?

Shepard Fairey: Well, it made me think about the power of symbols and how the, you know, the globe, even though it seems, the world seems vast, it’s actually not that big and that everything we, you know, we put into the air we put into the water affects the, I guess you, you know, I was considering the Gaia concept before I even knew that word but didn't. You know this is a planet that breathes and it needs to be held to breathe clean air. So, you know, I really like the way that each person could see themselves in the planet itself with that image. And I think that even before the Internet I realize that we’re all confronted with so much white noise that images that convey a message powerfully, iconically, using symbols that are relatable, that was an important tool of communication. And I saw artist far too narrow and cryptic, often and elitist. So, I was always looking for examples that sort of bridged high art and that punk rock ethos that have been so important to me as a developing teenager.

Greg Dalton: And we should mention for people who may not be familiar the Gaia concept is this idea that the earth is a living organism that's pulsing and that everything's working together as though it was an organism. You recently completed a mural in the arts district of downtown Los Angeles called “drink crude oil” describe that mural and what you were provoking with it.

Shepard Fairey: Well, it’s a piece that has kind of a collage aesthetic and I look at advertising as this insidious force of shaping people's behavior. And within that piece there is a Coca-Cola bottle but instead of it saying Coca-Cola in the same type style it says crude oil, so it says drink crude oil. And then there's an oil derrick and a flame and a guy who looks like a soldier, but it's a gas station attendant with a gas nozzle and it says, “we never stop charging” and it's making the correlation between the way that the economic forces of the fossil fuel industries and the accumulated power of that industry means that they can keep reinforcing their message through advertising and lobbying. It’s something that it's difficult for the average citizen to overcome and it's even difficult for governments to overcome. But within this piece there's a woman and you could say an activist for environmental justice who’s wearing a hat with a flower with a globe in the middle of the flower who you know in some ways like you know, in this she’s metaphorically up against and in this piece is literally up against all of this propaganda to maintain the structure of the economic and functional structure of how the fossil fuels industries works now. And it’s something that I think people when they realize that their pawn in someone else's plan they go wait a second, I don’t know if I really want that. And it’s one of the reasons I use obey in my work. I'm not encouraging people to obey. I'm actually encouraging them to question obedience by taking what's in the ether, which is all these different unseen forces to make you fall in line with someone else's agenda and crystallizing that into the direct command to obey so that people go, obey what, hmm, do I really want to?

Greg Dalton: Right. And so much of your work focuses on that concentration of power and fossil fuels are highly concentrated industry and a lot of power. How do you think about that speaking for the climate emergency we’re up against that huge concentrated power with a lot of fragmented power?

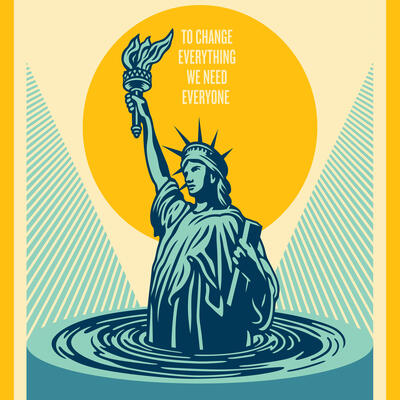

Shepard Fairey: Yeah, well that's where it's actually going to take community organizing voting people choosing how to spend their money that is, in a way a very strong message and vote. Capitalism does respond to supply and demand. So, if you demand renewables, if you demand electric cars, they will respond. But it requires in a way a combination of all these things to reach a critical mass that changes the structure of the fossil fuels industry and how we think about energy consumption. So, I'm promoting all of those things with different art pieces I'm making and some of them, I'm encouraging people to vote, in others, I am saying you know look at this beautiful sacred environment that that we all value and we don't want to go away. And you know in other pieces, I might be saying think about your children's future. I’m basically using every strategy I can but it's important that people understand the severity of the issue, but it's also important that they don't feel paralyzed because it's too overwhelming. So, I'm always trying to see how I can get the balance right in my communications with both the text and the imagery I'm using.

Greg Dalton: Right. Convey urgency but not alarm people so much that they shut down or that they get numb to that. You can’t be on high alert all the time, right. I mean adrenaline doesn't work that way.

Shepard Fairey: Right. And, you know, and the feeling of hopelessness is very demotivating. So, keeping people motivated is important.

Greg Dalton: And you have said that you embrace what you call an inside out strategy working with the establishment you described kind of the outside. Describe what you mean from the inside.

Shepard Fairey: Well, for years I couldn't survive just as an artist, so I did a lot of marketing and design projects with corporations. And whenever possible if the corporation that was approaching me liked my work and liked a lot of the ideas in my work then I would encourage them to, you know, be courageous about putting those messages out. So, in a way using you know using their very powerful machinery to put across the messages about equality, environmental responsibility, and democracy that I think are important. And then oftentimes, even though there's a fear in the corporate world that something will diminish the support with certain consumers actually taking a stand, frequently bolsters loyalty and support. So, even if that might not pan out that way, if for a moment I can get them to do the right thing that's what I'm gonna be trying to encourage from my position of very little power, but I use what I can.

Greg Dalton: Subversive on the inside. So much of environmental messaging can be kind of righteous and preachy. When you are creating art related to environment how do you approach that kind of not being kind of holier than thou?

Shepard Fairey: Well, it's a tough thing and sometimes I try to use humor. I mean, I think even the drink crude oil piece has a little bit of a dark humor, dark, sticky humor. There’s another piece that I did based on a photograph I shot, looking from Williamsburg into Manhattan and there's some factories there and it was a really beautiful sunset, but I made an illustration where the pollution from the factory is creating the smoke is going into this gold and orange and black sunset. And then there's a couple standing there on the waterfront looking across at the sunset and the caption is these sunsets are to die for. And, you know, I think that when I have a little bit of humor in there but you know that's also pointed that that's a way to not just be on, you know, this sort of Debbie Downer and have a cool factor have a style to what's there. I'm taking a lot of different approaches but rarely is it just save the whales. I do want the whales to be saved, but it's I'm trying to find things that draw people in before they just instantly reject something as to hippy dippy or asking them to have to consider their imperfection in any of their behaviors. It's more seducing people with something that maybe we'll get them to reflect upon it and make their own choice rather than feeling like they're being judged.

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation about the power of art. If you missed a previous episode, or want to hear more of Climate One’s empowering conversations, subscribe to our podcast wherever you get your pods. Coming up, Shepard Fairey on the power of human protagonists in his work:

Shepard Fairey: I desperately want people to care about these issues and I've tried a wide range of approaches with my art. And I feel like every action makes a difference but this is an issue that we really have to break through on.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton, and we’re talking about the power of art in the climate crisis with Shepard Fairey. Though much of his art is focused on climate and the environment, he’s best known for his “hope” portrait of Barack Obama, and gained more acclaim for posters he created for the Women’s March. I asked him why he thinks his environmental work hasn’t broken through in the same way those others have.

Shepard Fairey: Well, one I think that, for example with the Obama the much of the world was paying attention to Obama and had a range of feelings, but when I created an image that was a good symbol for him as a human being, rather than just being like his logo which is a great logo for his campaign. There was an immediately transmittable icon for him. And so, it benefited from that. However, you know, the We The People series was based on archetypes. It was saying that this Muslim woman or this Latinx woman or this Black boy were all equally American, equally human, equally patriotic. And I think for a lot of people who feel like they are not well represented within, you know, what it means to be American or any of those other things. That, you know, as well as people who want to see more inclusion though those archetypes made sense, but they were all about humanity from Obama to that or about humanity. And the environment is a much more abstract idea. Yes, we all live within this it should definitely arouse some sense of what's at stake for humanity in us, but I think it's less immediate. And I think it's the way we find human form for almost anything that we think is you know, inspiring or sacred. With some of the images I've done, that idea of the human connection to the environment and things being sacred have been important to me. I did the Protect The Sacred image, which was about respecting Native American tradition, as well as respecting the environment based on that idea. And I know that within certain circles that that image did really connect but --

Greg Dalton: I have it in my home.

Shepard Fairey: But nothing has broken through in the same way as like you said as those other images. And, hey, if there's anybody that thinks they have the winning formula I'm open to suggestions because I desperately want people to care about these issues and I've tried a wide range of approaches with my art. And I feel like every action makes a difference but this is an issue that we really have to break through on and you know some things that are going to compromise life on this planet might already be too late to fix, but we’re an innovative people. So, we have to encourage people to care and to take action. And that's from the most brilliant scientific minds to somebody that just changes a minor aspect of their habits around energy consumption, but we probably all gonna have to do something.

Greg Dalton: Right. I think if you ask a lot of people on the street without thinking what do you think of climate change. They would think of polar bear may be a smokestack. A human face is not easy to come up with a human face even a villain, right. The environment is seen as outside of us, over there, separate somehow, we’re not part of it.

Shepard Fairey: Well, very true, but several of the pieces I've made have used a protagonist within them because I know that portraiture is alluring for people. So, whether it’s the drink crude oil or several other images there’s one I did call raise the level that my wife is in it. Another one called fan the flames with a woman with a fan with a globe on fire within the fan. And it's not encouraging people to fan the flames and saying yeah, we continue to fan the flames unfortunately, that for all the things that we’re doing there's a lot we’re not doing. And I don't wanna discourage people because I think there’s stuff that’s happening that's encouraging but we need to do more. So, all of these things are hopefully ways for people to see how every individual's actions make a difference and how there is a very human connection to this issue. It's not just about polar bears or leopards that are endangered and all of those things I think affect people emotionally and might actually be the prime driver for some people, but I think it requires a lot broader of a sort of swath portfolio of approaches in order to touch everyone.

Greg Dalton: The climate conversation is often driven by facts and charts, and although it does have human dramatic elements to it. How do you think about the relationship between art and facts and how people are able to receive that?

Shepard Fairey: Well, I wish people were driven more by facts and I claim to be, but I know I'm very emotionally driven just like everyone else. We feel things and then we look for an intellectual justification for those feelings. And that's why we can be led astray so easily by nefarious forces. Now, when someone with what I think is an altruistic intent can make something that's emotionally resonant that leads somebody to then care about facts that maybe that same person is presenting, that's a beautiful thing that's what I'm striving for often. But I know that I have to lure people in with something that connects emotionally.

Greg Dalton: You got to start obviously with obey the giant sort of cropping up in public spaces and done a lot of your work in those public spaces. And climate is a tragedy of common public space we are pumping pollution into the global commons, the air and the water, and individuals in every scale: personal, corporate, national acting ways of the rational for themselves and damaging to the public to the commons. I'm curious how you think about that parallel between public space as an artistic expression and public space that’s being polluted by our activities.

Shepard Fairey: Well, I'm glad you brought that up because it's something I've considered a lot and I always felt as a, as a street artist that the public space is really meant to be for the community. Anybody that participates in democracy can appreciate the idea that we all should be able to shape what our world looks like or at least what our communities look like. And yet corporate advertising and government signage were pretty much the only visual communications in public space and I always thought there should be more art. And I initially said, well I'm gonna do that with or without permission and now I get invited to do things. But one of the things a lot of people don't consider about these commons and it’s something I learned about from my friend Adam Werbach who is the youngest president of the Sierra Club that idea of common assets air and water that we all need to be healthy yet certain companies really benefit financially from polluting or destroying these common assets. And so, the way people should think about that is that these are owned by all of us yet they’re compromised by predominantly by a very powerful few. And yes, we all can decide what kind of car we want to drive and those few often say, yeah, yeah, it's your carbon footprint, you know, it's because you drive an SUV, but really we need to be thinking not only about how we’re contributing to the maintenance of these common assets or the health of these common assets but also how we need to vote to make sure that the people who wreck the environment also pay to restore it.

Greg Dalton: Shepard Fairey is a renowned artist and activist, perhaps best known for his 2008 hope portrait of Barack Obama. You were born in Charleston, South Carolina where seas are rising at an accelerating rate, an inch every two years. Floods are increasing, sometimes making the hospital inaccessible. Your dad's a doctor, your family still lives in Charleston. How do you feel about your home being threatened?

Shepard Fairey: Well, you know, I feel the same way about it as I feel about Bangladesh being threatened and about New Orleans being threatened. You know, luckily my parents have always cared about the environment and they’re sort of moderate, they don't like to rock the boat. But they believe in truth, they believe in protecting the environment for future generations. And Charleston is an extraordinary place I think a lot of people who live there and even people who would visit there would like to not see it submerged. But, you know, the collective will have to be there you can't just build the battery in Charleston higher which there is one of the things they’re talking about. My parents lived right there where the waves crash over during hurricanes. I've been through several of them myself where it's terrifying. And you know hurricanes have happened, but they're intensifying. And if you live through it the feeling of powerlessness is really traumatic. And I think that we need to be considering that a lot of these things are intensifying and that not only is it going to be bad for our parents it’s gonna be bad for displacing populations all over the planet. So, if you're soft on immigration, great, be welcoming. And if you're not soft on immigration maybe you should consider climate as something that you take seriously.

Greg Dalton: Right. It can bring a lot of people north.

Shepard Fairey: Yeah. And, you know, I don't know if I want the Floridians migrating to California where or anything, I'm kidding, but this is --

Greg Dalton: Already people are moving out of Florida. Some are going to Michigan into places that are --

Shepard Fairey: Yeah, this is serious stuff. And I just see the need for immediate but incremental change to be something that people need to consider how much less of a difficulty that is and how adaptable we can be now if we keep moving now and we move more quickly now than when potentially there's a critical mass for some things that are unstoppable. And if they are to be stopped require a brutal, brutal compromise in things that you that we now define as our way of life.

Greg Dalton: How concerned are you personally about climate disruption? Do you lose sleep over it, do think it'll affect you directly, personally, or is it already?

Shepard Fairey: Well, I mean it's affecting some of my decisions about what car I drive how far away from my house is my studio. But these are things that I'm just looking at us how to be responsible. I mean I just was reading an article yesterday about how Joshua trees are disappearing from Joshua tree because they can only take so much and this is heartbreaking. A lot of people don't understand how fragile everything is that we’re living in that we take for granted it's fragile. And so, this is how it's affecting me psychologically that I'm realizing that we as a species are not, we’re not as thoughtful as we should be. And that the fragility of things is something a lot of people aren't considering.

Greg Dalton: Speaking of fragility, you read the book White Fragility and been working to understand your own privilege. You’re reading John Lewis’ autobiography I think now. What are been some recent revelations for you about your own power as a white man and what are you doing to be a good ally to people of color?

Shepard Fairey: Well, I've been making work since I grew up in Charleston where they started the Civil War and it's very racially divided, economically. I’ve been aware of racism almost my whole life and yet I learned a lot in the last little over a year, yeah, little over a year, right. George Floyd was killed a little over a year ago. And because I'm a white straight male I had a lot of blind spots.

Greg Dalton: Me too, yeah.

Shepard Fairey: And so, you know, working with a lot of racial justice organizations collaborating with artists of color trying to make sure that I'm not, whether it's Native Americans or any other people of color that I'm supporting rather than taking the microphone or the spotlight. This is all stuff that you know I'm thinking about and I think a more precise sophisticated way now. And because I do believe that equality is anything short of an equality on every front is uncivilized. I care about all of this and even when it makes me have to admit that there were things I took for granted or things that make me uncomfortable about how to forsake privilege that I need to do it, because otherwise I'm not practicing what I preach and that's important to me. And you know there's a lot of emotions and sometimes I feel my feelings are hurt by you know people misinterpreting some of my statements or some of my efforts as me trying to be a white savior. I just want to be a good ally. I want things to be more fair and I'm always open to hearing better ways to do it. I'm listening.

Greg Dalton: Street artist and graphic designer Shepard Fairey recently joined us for a Climate One live event. You can find the full conversation on the videos page on our website. Today we’re talking about the power of art in responding to the climate emergency. Coming up, hip-hop artist Mystic talks about the value of humor in dire times:

Mystic: How do you make the climate crisis funny, right? Something that’s not funny at all, how can we talk about it in ways where people can think about it in different ways and we can start to have conversation.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. We’re talking about the power of art in connecting with people, and driving action around the climate crisis.

Mystic is a Grammy-nominated hip-hop artist, community educator and a program manager with the Hip Hop Caucus.

Mystic: The Hip Hop Caucus is a national as well as international nonprofit organization that is really engaged in human rights work and civil rights work. One of our core areas is the climate crisis and pursuing climate justice. And we have a films division and I am the program manager for that films division. And the films division focuses on and produces films connected to climate justice and the climate crisis.

Greg Dalton: Right. And we’ll get into that. I think most people think of hip-hop in terms of music, but it's really a broader cultural movement, right?

Mystic: Absolutely. I am a hip-hop artist and I have been a hip-hop artist for oh my goodness almost 30 years now. Hip-hop as a culture contains many different elements. It's the emcees it’s the DJs it’s the B boys and B girls. It's the graffiti in the wall art, you know, it's a vast and dynamic and beautiful, beautiful culture. And so, at the caucus we believe and I also believe individually as a hip-hop artist that the culture, hip-hop culture can be used to engage our communities around justice around healing around knowledge building and sharing. So, hip-hop is a powerful, powerful culture and medium.

Greg Dalton: And many people think of the performers are often black, but white people account for I believe the majority of hip-hop listeners. So, is the Caucus reaching across the racial divide in engaging them on climate and other issues?

Mystic: Yeah, we definitely are the Hip Hop Caucus. We want to engage the communities that are being most impacted by inequalities and injustice. It's not simply engaging because we recognize the challenges that exist but because the solutions are often coming from the communities that are being most impacted in this context impacted by the climate crisis. And so, sure, hip-hop embraces everybody but the organizing that work that we do and the Hip Hop Caucus is an advocacy organization. The organizing that we do is absolutely targeted to, black, brown, indigenous and economically vulnerable communities.

Greg Dalton: We spoke before you said you can’t have a revolution without art. You can’t have a change without art. So, how can art change the trajectory of the climate emergency?

Mystic: Art plays in its many different manifestations, right. It plays this role of opening up pathways for communication and understanding. It helps to shift the culture that is felt in the community, in the room. It can help shift the culture in the context of legislation and policy makers. Art allows people to tune in, right. I think sometimes when we’re enjoying ourselves or engaging with art, some of our defenses come down. And particular for me as a music artist music is a universal language, right. I've had the privilege to study in South Africa and to work with children in Haiti and children and youth and indigenous youth in Canada. And you know children in various parts of the nation and part of what I know is that people sing along to songs whether they understand what the words they’re saying but the art itself is a bridge. It helps to build a bridge across man-made borders and the beautiful variety of cultures that exist. I also think that art allows, right, like art is also the voice of the unheard and the excluded if we’re using it right, right? And if we understand the power of what that art is. Art has this unlimited power to open up conversations so that we can work collectively. I also understand having engaged in research on culturally relevant arts education that there are people who also use art that because it's so powerful people can also use art to kind of subvert the will of the people and to push forward, you know, authoritarian messages, or you know so we have to be careful, and we have to understand that art can be powerful no matter who is using it.

Greg Dalton: Right. We talk in this episode with Shepard Fairey who talks about the potential for art to be propaganda. You’re primarily known as a musician. You're also the program manager for the Hip Hop Caucus, Think 100% Films Division. So, can you talk about the different art forms and how they can reach people in different ways.

Mystic: Yeah, so our first film from Think 100% Films is called Ain't Your Mama’s Heat Wave which is a comedy special. But I want to be clear that it is not a film that was simply developed and put together to be an organizing tool. It grew out of an organizing project in Norfolk, Virginia in the Hampton Roads area. And so, to use comedy which can kind of again bring down our defenses and in the comedy special how do you make the climate crisis funny, right. Something that's not funny at all how can we talk about it in ways that open up where people can think about it in different ways and we can start to have conversation. It's also in this rich, rich tradition the use of comedy in black movements the civil rights movement, on the Chitlin’ Circuit and in various other ways that comedy allows us to survive what is so painful. Sometimes you have to laugh to stop from crying those kinds of statement that we all know.

Greg Dalton: Gallows humor.

Mystic: Yeah, exactly. And so, Ain't Your Mama’s Heat Wave is really about joy as part of resistance. And in a time where we have multiple pandemics that are intersecting, you know, COVID and police brutality and pollution and poverty. We still need to be able to thrive in our communities and the comedy special as an expression of art and film as visual storytelling and visual narratives, open up this opportunity to laugh and also recognize that the community in which it was filmed is sinking and floods even on sunny days. And so, yeah, we can laugh and this is part of joy is resistance. But let's also raise the awareness and let's also continue to organize. This is a call this is an emergency that’s happening and we need to understand that the climate crisis is not just in other places in the world, but it's happening in communities in our nation in Black communities.

Greg Dalton: Well, one of the best lines in Ain't Your Mama’s Heat Wave is Mamoudou N’Diaye talking about how white people rank their environmental concerns.

Mamoudou N’Diaye: And I want to tell you just a report from these white climate crisis rooms, what they worry about. Straws, sea turtles….. Black people. It’s not a good order.

Greg Dalton: So, that’s a hilarious and somewhat uncomfortable example of comedy speaking truth to power.

Mystic: Yeah, well I mean it’s important to continue to recognize and discuss that there are there currents that you know we have a history of white supremacy in this country that is still here. And that the environmental movement has often been white led and exclusionary and part of what was put together to engage people was to center animals, as opposed to humans, right. And again this comedy special filmed in a community that is full of black people that is sinking who are being displaced and saying, look, folks still care mostly about these turtles and polar bears, but we have Black people here and as Black people we are worthy and valuable and we deserve to have our issues in connection with the climate change addressed, right, in a way that preserves culture that preserves dwellings that contributes to improvements in health, right. Like Black people are worthy. And so, we laugh about it, right, like yeah, they care about the animals and not the Black people. It is painfully funny but it's the brilliant use of comedy and that platform that room the people who were listening when it was filmed were primarily Black folks. And everybody gets that yeah, they don't really see us as being valuable. So, that beauty of comedy for what's painful, turning it into something funny so we can kind of talk about and explore what that is.

Greg Dalton: And I think relief because climate is heavy to hold and think about all the time. I wish there was more climate comedy because it pierces, it gives us permission to laugh and release the things that we’re holding that we may not even know we’re holding and we need the comic relief because climate is dark. And I think if we could laugh about it, we might talk about it more.

Mystic: I agree with you. I mean I think that's the point of Ain't Your Mama’s Heat Wave, right, is let’s laugh about it, but let's also understand and we get that relief and we can practice in joy but that it opens up the space for us to talk about what's really hard. It lowers defenses, right, when we’re laughing. It also literally releases like endorphins within our body that I think can help us, help make us feel you know feel may be more open and better. I don't have the scientific research to say that specifically. And as far as we know Ain't Your Mama’s Heat Wave is the first comedy special that is connected to the climate crisis it’s absolutely the first Black one.

Greg Dalton: Mystic is a Grammy nominated hip-hop artist community educator and a program manager with the Hip Hop Caucus. I’ve been learning a lot lately about different modes of communication, here we’re talking about art and music and street art. Traditionally most science communication and this includes a lot of climate communication follows the information deficit model. If we just give people more information that's what's needed to affect change. And then there are sort of the empathy or emotional deficit model if we can get people to feel more that will prompt action. I’m curious how you think about this as a musical artist and now you’re involved in film, that emotional connection versus, you know, do you need to get people to feel more or know more?

Mystic: Right. There is so much information that's hitting us from all angles in where we are, right. Whether it's via social media or the radio or in our communities we’re constantly being bombarded with information and that can be an overload. Scientific research and when it's presented in this kind of, we need more information is that for, the understanding that information is not guaranteed. It's not that people lack intelligence. It's just how do you take that science and that data and apply it to your everyday life and what you're experiencing. Like what does that science and data mean when your community floods even on sunny days, right. And so, I think that part of the power of music and film and just creativity and culture is that that is about connecting on an emotional level, but you also have to take an approach like look. Typically, my verses are 16 bars. I can't try to fit in there the science, right. As academic I can actually read some of those scientific documents and the data.

Greg Dalton: There’s no footnotes in lyrics, right?

Mystic: Right. There’s no footnotes in my lyrics. But it’s figuring out I don't just create my art for myself it's about communication art. And so, I think in some ways it's equally if not more powerful than just offering more information that is in the form of data and scientific language when you can use art. More people can connect with that they can gravitate to it and it can be cool and it can make you move and it can make you understand in a different way what's happening. You know when we talk about the climate movement or the environmental movement more broadly, the movement is there have often been disconnects between the crisis that we’re facing and what's happening. And then how do we create information and knowledge and resources that is culturally relevant and responsive in ways that the communities that we want to communicate with can receive what we’re trying to say, right.

Greg Dalton: How do you know if your art has any effect, it can emotionally connect but how do you know if it causes change and do you have any specific examples of when art has really changed someone's mind or really had a tangible impact?

Mystic: I probably have more than we could talk about in the space of this conversation. I have fans across kind of areas maybe that people wouldn't expect, but people who are police officers and people who work in government as well. And they too will have conversations though maybe ask me and challenge me about something I’ve said or say, hey, I'm not that kind of person, right. But that they've come to me and said that listening to my music has given them ways different ways to think about our communities and to think about the ways that they serve. And maybe it's not the art itself but being an artist and being nominated for awards, but being artist who has always used my platform in connection with justice. It might not be the music but it's my platform that gets me into the room to speak with politicians that gets me into the room to be able to speak to what is on the table in terms of legislation and the importance evident to advocate for what our communities need. So, I think it's broad and diverse it’s literally the music impacts people and what they believe in and how we heal, but that the platform opens up these opportunities for me to speak with people in positions of power.

Greg Dalton: So, as we wrap up I'm just curious to know how do you measure the success of your own artistic endeavors and what keeps you up what gives you, how do you deal with your own sort of roller coaster of hope and fear around climate?

Mystic: Yeah, let’s see. In terms of measuring my own success as an artist. The success was in the first person who didn't kill themselves because they saw some light an opening for healing in my music, right. To even save one life means that my art, my craft has been successful, right, in the most intimate way.

Greg Dalton: That's power.

Mystic: Yeah. And then I would also judge the success of my art on how it inspires community and how it helps to build community. In terms of my fear and kind of the heaviness in connection with the climate crisis and how I try to keep my balance and I actually talk about it is a state of grace right. And I say find your grace and stand in it. That I draw like I'm able to deal with the heaviness and just like you know the darkness of it all because the children are so inspiring. I literally mean the children, right, as somebody who during COVID and prior to COVID was a lead kindergarten teacher facilitating arts. The whole world can be falling down around you but you still have to find the joy and the magic. And so, they give me hope they give me faith they make me understand that me being broken doesn't actually serve the purpose of moving forward. And so, as somebody who has experienced pain and a lot of sadness. The climate crisis is like one huge additional layer but like I know and believe that we must hold on to our joy. We must practice joy on a daily basis. And so, that's how I navigate through it, but it's also I want to say that it's not about denying when you just something happens or a piece of legislation gets pushed or there's a storm or a climate event that results in a massive loss of lives and destruction of communities. It’s okay to, you know, cry and be in that place but, you know, then we move ourselves back to stand in our grace, right, and then we can go make art about it. And as I told children like you can make any kind of art that you want to make if you ever feel sad make some art. You don't have to share it with anybody. You don't have to share it with me. Just know that you as a creative as an artist and as somebody who has the power to change the world that the arts are here for you in your life. And so, yeah, the art is a massive piece of how I make it through.

Greg Dalton: Well, thank you so much Mystic for sharing your story and your insights.

Mystic: Thank you, Greg.

Greg Dalton: On this Climate One... We’ve been talking with hip hop artist Mystic and street artist and graphic designer Shepard Fairey about the power of art in responding to the climate crisis. To hear more Climate One conversations, subscribe to our podcast on Apple, Spotify or wherever you get your pods. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. It really does help advance the climate conversation.

Brad Marshland is our senior producer; Ariana Brocious is our producer and audio editor. Arnav Gupta is our audio engineer. Our team also includes Steve Fox, Kelli Pennington, and Tyler Reed. Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.