Oppressive Heat: Climate Change as a Civil Rights Issue

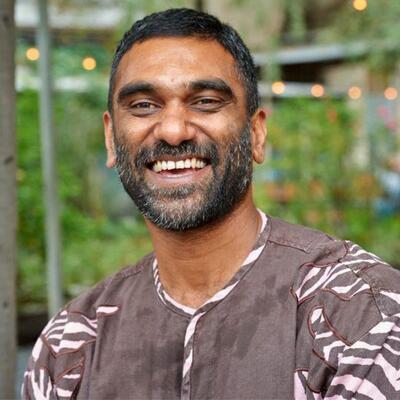

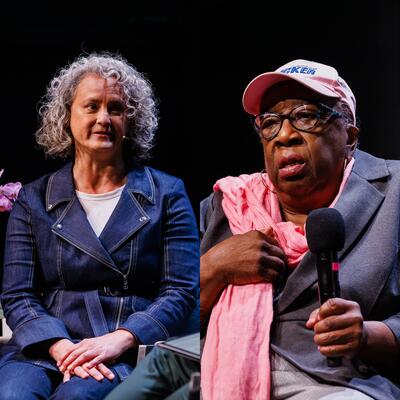

Guests

Ingrid Brostrom

Rev. Dr. Gerald Durley

Mystic

Summary

While the environmental movement is typically associated with upper-class white folk, it is also a civil rights issue. Communities of color often live closest to factories and refineries that spew toxic pollution. That’s one reason why polls show more African Americans and Latinos expressing a serious concern over climate change than whites. So why do environmental movements lack diversity, and why has it been so difficult for nonprofits to reach communities of color? We talk to hip hop artist and activist Mystic, civil rights hero Rev. Gerald Durley and civil rights lawyer Ingrid Brostrom to learn more.

Full Transcript

Announcer: This is Climate One, changing the conversation about energy, economy and the environment.

When it comes to the impacts of climate change, minorities and economically disadvantaged communities usually suffer the most. .

Ingrid Brostrom: They are getting the double whammy of being physically impacted by the local pollution, but they’re also gonna be impacted first and worst by climate and they’re gonna be less resilient.

Announcer: Which makes climate disruption more than just an environmental issue.

Mystic: Climate change was always part of the platform in terms of connecting it to civil rights and to human rights and to social justice.

Announcer: And just like in the civil rights movement, churches are getting involved to make the moral case for climate action.

Gerald Durley: The environmentalists, the conservationists cannot keep this in their own little bailiwick, in their own silo. This is big.

Announcer: Civil rights and climate change. Up next on Climate One.

Announcer: How does climate change connect with voting, education, and other civil rights? Welcome to Climate One – changing the conversation about America’s energy, economy and environment. I’m Devon Strolovitch. Climate One conversations – with oil companies and environmentalists, Republicans and Democrats – are recorded before a live audience, and hosted by Greg Dalton.

What comes to mind when you think of global warming? A polar bear, or maybe a melting glacier? If you’re Hispanic or African-American, you might think of a child with asthma worsened by a coal plant near your home. People of color often live closest to the large sources of carbon pollution that are hurting their personal health and the health of the planet. On today’s show we look at climate disruption through the lens of civil rights, with three guests on the frontlines.

Reverend Gerald Durley worked alongside Dr. Martin Luther King in the Civil Rights Movement. He’s pastor emeritus of Providence Missionary Baptist Church of Atlanta, and he’s also on the board of Interfaith Power & Light, a religious response to climate change. Mandolyn Wind Ludlum, better known by her stage name Mystic, is an American hip-hop artist and activist. And Ingrid Brostrom is Assistant Director of the Center on Race, Poverty & the Environment, an advocacy organization.

Here’s our conversation about oppressive heat -- climate change and civil rights.

Greg Dalton: Reverend Durley, let’s begin with you. You were in the National Mall, 1963 when Dr. King gave his famous speech and you went back 50 years later. How do you see civil rights and climate change as connected?

Gerald Durley: First of all let me thank Climate One for this very important discussion at this time. It’s so important because in any movement there has to be a period of time where we get all of the facts together so it’s not considered fake news. But we can come together and understand how important this is. In 1963, that was my senior year in college and we were concerned about the civil and human rights of all individuals. And we fought a good fight I thought and then 50 something years later it’s still the civil and human rights that everyone should have the right to clean air, toxic free water and these kinds of efforts. So we see the analogies between what we were fighting for then and what we've got to fight for now. It is a right of everybody that we have access to these kinds of area. So we see it now and particularly in the faith community we were beginning to now organize around this. And if we can organize by bringing people to another level of awareness, then we can move to the strategy session. That’s the foundation of any movement.

Greg Dalton: Mystic, you grew up with a mother who’s an environmental advocate and activist, and how did you come to this I guess you couldn't escape it because you grew up with it coming to the climate connection.

Mystic: Yeah, I mean I grew up with my mother here for a long time in San Francisco. She was an activist and advocate. Worked with farmworkers in the Central Valley in the 80s she worked with folks coming from Nicaragua and Guatemala around asylum. So she was just like always dedicated to people and the world and the environment. And as time has progressed as we have learned more knowledge, as we have gained more facts about what climate change means not only around the world, but in the communities that are most impacted, which are traditionally more impoverished and are traditionally folks of color. That, you know, I can't escape getting the information shared with me and it can be as simple as if I had air freshener in my house that she would explain to me what the toxins were. She would explain to me that I should go buy one where I can put my own essential oils on them and therefore it's healthier for my house and healthier for me. So it was kind of there in something that I was interested in but when I began working with the Hip Hop Caucus which is national and growing international human rights and civil rights and social justice organization started by Reverend Lennox Yearwood over 10 years ago. Climate change was always part of the platform in terms of connecting it to civil rights and to human rights and to social justice. And so to have the opportunity to travel to other places, you know, has pushed me in that direction as somebody who really I know it can be a kind of flag world to say global citizen but as somebody who works with children and loves children all around the world to know that millions of children are being impacted by climate change and will continue to be so. That’s what drives me to advocate in this area.

Greg Dalton: Thank you. Ingrid Brostrom, there’s a perception that the environmental people who care about our climate change are coastal, Caucasian, et cetera. So tell us what your organization is trying to address that hasn't been addressed by sort of the broader environmental groups, bigger environmental groups.

Ingrid Brostrom: Yeah. And I think that perception is actually very wrong. When you do polling you actually see that people of color, poll the highest on the need to address climate change and address it quickly. And it makes sense because certain communities are impacted by the same toxic facilities that are causing global warming and climate change. And so, you know, we are working directly with communities in California Central Valley. So a lot of farmworking communities it’s impacted by pesticide applications, it’s impacted by fracking operations, refineries of course all of the biggest freeways go right through the Central Valley. And so they’re inundated with both local pollutants from all these facilities and sources as well as carbon. And so they are getting the double whammy of being physically impacted by the local pollution, but they’re also gonna be impacted first and worst by climate and they’re gonna be less resilient. They’re gonna have less money to leave the area they’re gonna have less money for air-conditioning and other ways of that other communities can be more resilient. We’r

Greg Dalton: Jose Gurrola is the 23-year-old mayor of Arvin, an agricultural town in California Central Valley and that town suffers from some of the poorest air in the country. In 2007 the EPA noted the community has some of the highest levels of smog pollution in the United States. Let’s listen to the Mayor.

[Start Clip]

Jose Gurrola: Arvin is a small agricultural community population just over 21,000. About 95% Hispanic and the rest divided between Muslim-American population, African-Americans and Caucasians. Low-income community. We passed resolution in support of the Paris climate agreement. I believe we’re the only city in the county, and possibly in the Central Valley to do so. In my first term, there was a pipeline leak that was leaking gas and about 20 of my neighbors on my street were evacuated for more than eight months because this contamination was in the soil. It was in their homes and during that time I try to adopt a temporary moratorium on oil and gas operations, which include fracking. And if this happened in an affluent area in Bakersfield, it would be making the front page of the newspaper every day, but it wasn't. And a large percentage of the people living within one mile of a fracking are people of color. You know, these things are structural and institutional it’s environmental racism. I am fully aware that I'm trying to operate in the system that was meant to keep my community oppressed and keeping people from participating in local government as well. I've decided to speak out rather than just, you know, as a 24-year-old just I can just keep quiet and play nice.

[End Clip]

Greg Dalton: That’s Jose Gurrola mayor of Arvin, California. Reverend Durley, he said pretty strong things there that it’s intentional oppression where fossil fuel and the way that our economy works to provide energy.

Gerald Durley: First of all, I was so pleased to hear from the mayor at that age group. We used to talk about passing the torch on and what do we say to our young people and I'm convinced the torch is never passed on, you take the torch and you move ahead. No one passes it because we like power. We like to have privileged positions and in a capitalist society, it’s about the money. We always say follow the dollar. So consequently it is -- he used the term environmental racism. And we look at the toxic waste often fracking in the Midwest, but there is a certain kind of and particularly when we bring the faith aspect into it. When I would talk to many of the and I’ll just said many of the white evangelicals throughout they would constantly hold on to that this is created by God, not realizing these were man-made situations. But they did it because many of the people in the congregations were owning these companies. So when they own the companies it was profit over people. So consequently, we've got to go back and if you say that they said let's start off, let's oppress people in this area because they're Latino or black. I think they follow the dollar terms of replacing toxic waste dumps because of the land where they get the land at a certain amount and those kinds of laws that were passed. And so when you put those two things together the profit motive a lot of time it override the racist thing. I mean the cotton plantation was around money. So when you really go back and look at it, it has not changed over the years. That's what now we've got to look at the human life and what it really means in terms of just going after the dollar.

Greg Dalton: So those fossil fuel refineries plants are placed in places where the land is cheaper. The people have less power to out to fight back.

Gerald Durley: Fight as far as legislation is concerned. Plus you understand that many times people have said while on people of color and particularly in African-American community and Latino community. Why aren’t they are more involved. But you have to understand one thing, people move from a psychological point of survival. And when you've got police brutality when you got rent when you got poor education, when you've got unemployment those issues that are very bread-and-butter issues is not a matter of people are not concerned about the environment. They've got other pressing issues. And so as long as you can keep that in front of people you can do the land, you can put different kinds of programs around them, they just don't know. And I think that is why this is so important now I know in 40 states Interfaith Power & Light is really trying to work with the base of people to bring them to a level of understanding what is actually going on. I had no idea about this eight years ago. And I consider myself fairly knowledgeable, but I have --

Greg Dalton: Highly educated man but the climate was not on your radar.

Gerald Durley: It was not on my radar. A lady, she came up to me and said this is very important and I didn't pay any attention to her. But she joined the church and so I started listening to her. And she said I wanna introduce you to my husband. Her name was Jane Fonda. Her husband was Ted Turner. So I said you’ve got my ear. But it wasn’t about polar bear so much as it maybe I could get a grant from these people.

Greg Dalton: Follow the money, right.

Gerald Durley: Yeah, follow the money. But then as I begin to get in and look at the devastation in particular those that I was called to serve, I begin to understand the importance of what it is that we have to do. Then I begin to see that there is no incongruence between faith and science and begin to connect the dots and allow people. Because people, when they find out that this is a despairing situation they will make the appropriate decision. So I got tired of so many major white who’s talking about minorities rather than talking with minorities and finding out what's going on in the rivers here North Carolina, South Carolina when suddenly it went down after Katrina with Jim Wallace and to look at those issues. Then it became then we've got to have that coordinating kind of understanding as to where we go. So is the deliberate effort to say we’re going to just disenfranchise people of color in these areas. I don't think that so much as evolved from following the dollar.

Greg Dalton: Let’s pick up on that Mystic, I mean environmental organizations know they have a diversity problem, they try. Where do they fall short? Do they not listen enough why is it so hard to bridge that gap?

Mystic: I think one of the most basic level it’s about who deems certain kind of knowledge worthy, right. And who deems the sanctity the quality, the purpose of lives differently. And so it’s one thing as a, you know, a primarily way, you know, environmental justice organizations to try to come to communities of color and show up and say well we have things to tell you, right. And we have all the answers for you and these are what the solutions are without ever taking the opportunities to say how is this impacting you and your family and your community. What would you like to see the solutions be and to start to talk about not just that we in communities of color need for the policy to change, but that we also need to be engaged. There’s a lot of money in climate change mitigation, right, and adaptation as we create more renewable energy sources. You know how about in communities that are most deeply impacted that there are educational programs to train people to build solar panels to install solar panels to really be engaged in. So I think it can be very well meaning but when you think about structural hierarchies and if the perception is that white folks are the leader within this movement and have that higher level of power and you don't help lift people up, right, not speak on behalf of people or poor people. But bring them to the table to speak for themselves to shape what the conversation is. And not just the conversation but what those solutions are that need to come. So I think that there has been a lot of outreach but I think the failure is also like you come to tell us things, you don't come to ask us how we’re organizing or what we want to do or what we want to see and what we want the future to be.

Announcer: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation about civil rights and climate change. You can subscribe to our podcast at our website: climateone.org. Greg Dalton will continue his conversation in just a moment.

Announcer: We continue now with Climate One. Greg Dalton is talking about climate disruption and civil rights with Reverend Gerald Durley, pastor emeritus of Providence Missionary Baptist Church of Atlanta. Hip-hop artist and activist, Mystic. And Ingrid Brostrom, Assistant Director of Center on Race, Poverty & the Environment,

Here’s your host, Greg Dalton.

Greg Dalton: Ingrid Brostrom, I wanna talk about the courts. Some scientists believe that dispensing facts about climate change and atmospheric carbon isn't really getting through to people and they're looking to the courts to do some things that the federal government has not done just as civil rights a lot of important things happened in the courts. Tell us what's happening in the courts on climate.

Ingrid Brostrom: Well the courts have not been friendly thus far. I mean there is a series of cases, you know, basically trying to hold companies liable for the climate change they are causing and actual damage to communities and they all failed. The courts were basically punting and putting it back on the federal government and saying this is who’s gonna regulate these climate pollutants, not us. So we've had a series of failures on that front. But there is a renewed energy and focus on a different type of litigation and that's really recognizing that governments in general hold natural resources and trust. And the atmosphere can be seen as a natural resource that’s very important for our future generations and the ability of them to live. And so we've actually seen some progress in this new legal theory, and I believe next year there’ll be more litigation on that front. There are right now in the world over 700 different climate cases. The U.S. is the home of the vast majority of those cases and so definitely litigators both here and internationally are trying to figure out different legal theories that we can test in the courts. And so we'll see what happens. Me, personally, I haven't had a great deal of faith in the court system divorced from other political and organizing avenues my organization in particular, we organize, is a biggest part of what we do is we organize communities and we do policy work and we also litigate. But the court system itself is designed to remove issues from the hands of the communities that are impacted and putting it on elite attorneys and their different legal theories. When the environmental justice communities, the communities of color that are so impacted by climate and by toxicities when we asked for support to make sure that we do not allow pollution trading as the way to implement that law, it fell on deaf ears. So it continues to be a really big divide and not not, I don't think the way we’re actually gonna solve our problems. So it really does have to be we have to be getting more voters we need to be changing the decision-makers. We need to be organizing the residents. We need to be changing the laws in Sacramento and Washington and let’s have a court case. So that’s where I think we’re gonna get those victories and it’s not gonna be the courts by themselves.

Greg Dalton: So explain what pollution trading is and why it's so controversial among certain communities.

Ingrid Brostrom: Yup, I mean pollution training is what it sounds like. It really is the ability to buy and sell pollution rather than reducing it at the source. And why it's so important for environmental justice communities and communities of color is if you look at carbon in isolation then perhaps it doesn't matter whether reductions are happening. But when you recognize that carbon is never emitted by itself, it always emitted alongside very toxic air pollution that directly impacts people living next door. Then, instead of reducing the pollution on site and instead you buy it from somewhere else then location really matters. You're not getting the pollution reductions that these communities really need right now they're being impacted on a daily basis.

Greg Dalton: So that’s for U.S. power company for example, can save some trees in Brazil, but still keep polluting in Mississippi or Alabama or Louisiana, et cetera. So they can clean up somewhere far away and still be dirty at home because it's cheaper to do that. Mystic you're working on voter registration, voter engagement with the Hip Hop Caucus. During the 2016 election 60% of eligible voters in this country voted. That’s up a little bit from 59% in 2012 down a little bit from 2008 when the exuberance of Barack Obama drove a lot of people to the polls. Why don't more people vote what can be done to get more people engaged out to vote. If they don't think it matters the last election ought to show that elections matter.

Mystic: I think on the most basic level, it's frustrating when you vote and you don't get what you voted for, right or you vote, but then the election is stolen, right. I’m a little bit older, so I'm like I voted in elections where that's not how it was supposed to turn out. That there was so much kind of a systemic approach to excluding people from being able to vote because they had been incarcerated or you know, whatever it may have been removing people from roles. And so I think there’s the frustration there but when we talk about bringing more folks to the table to vote and especially at the caucus we’re very interested in civic engagement among young people, right. As somebody who advocates for children and works with children and youth and like I firmly believe that children and youth are leaders, right.

Greg Dalton: But you think locally too is a better place. If you’re disaffected with national go local.

Mystic: Absolutely. Absolutely vote local.

Greg Dalton: Because they’re it matters.

Mystic: And we’re not partisan at the Hip Hop Caucus. So we’re not about telling you who to vote for or what to vote for. It's about get the knowledge understands who the people are who are running for these positions and what that impact is on your community. Who funds them, and so in that sense what's happening locally like your school board, you know, in your attorneys. But then of course your mayor and your governor may be voting for the president doesn't seem like it has the largest impact. Although I believe after this current administration that there is no way that we are going to be able to go back. I mean, I would hope that we will not go back to a point in a position where we say it does not matter to vote, but it's like let's engage more young people to push that through to lead it and let's force people who are currently in power who we’ve put in those positions to actually do what they said they were gonna do.

Gerald Durley: To hold them accountable.

Mystic: Yeah, to hold them accountable. And help transform communities driven by community solutions.

Greg Dalton: Reverend Durley you know some people who voted for Barack Obama who thought he was gonna change things, but he didn't.

Gerald Durley: I think he changed a lot of things. And that’s indicative of why somebody is trying to change things back.

Greg Dalton: Right, right.

Gerald Durley: He must have changed something, if you have to change it back, he must have changed something. If he want us trying to make it great again, it was never great for me.

Greg Dalton: Certainly trying very hard to. We’re talking about climate change and civil rights with Reverend Gerald Durley from Interfaith Power & Light, and the hip-hop activist and artist Mystic as well as Ingrid Brostrom for the Center on Race, Poverty and the Environment. I'm Greg Dalton. Reverend Durley, I’d like to ask you about scripture. You work a lot with people from different religious traditions and a lot of time you talk with the evangelicals and others but some people point to Genesis which says, be fruitful and multiply and that human should fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the sky.

Gerald Durley: Yeah. You’re talking about Genesis the second chapter, the book of Genesis. And even when you look into the Jewish, the Talmud and the Torah they all have opening beginnings of creation. And when you look at the even the Jewish liturgy talks about the stewardship in the beginning the book Genesis means the book of beginning. So consequently from our particular faith we see that God created a perfectly balanced ecological world where plants and animals and bees could come together. And he took the humankind to work with that to be the stewards of that. But now we as human beings we’re treating the planet like rent-a-car. We take it for granted, you know, it's something that we’ve take that privilege mentality. So we've got to go back and look what we've done because of our own greed over profit and greed of profitable people we’ve thrown that balance off and that's just what we see when the oceans warm up when the acidity of the oceans are so intense, when sharks don't even know which way to swim when salmon are not swimming upstream. We have done that but we can come back and justify it and say well maybe this is what God is doing. But God says I will give it to you take care of it. You have clean water, pristine water you have clean air, the birds, you’ll have enough to eat. The Indians understood the Native Americans in terms when they were hunting they care for balance but we now we move far beyond that. So the Scriptures on all for this, Islamic faith the Jewish faith speaks to that effect in a number of scriptures. And even the Christian tradition we have what we call the green Bible now where it demonstrates throughout the Bible where God speaks to the point of the mountains and the trees and the babbling brooks and what we're to do. But we’ve becoming inured to that and closed our ears to that and going our own ways and now we’re suffering. There’s always a consequence when you break a rule. He gave us a rule to follow. And the same thing in science, if you break a scientific rule you pay the consequences. If you stick a fork into an electric socket --

Greg Dalton: It doesn't turn out so well.

Gerald Durley: No. In the same thing with this it will breaking certain inalienable rights that have been given to us to do and we’ve abdicated our responsibility to take care of what was given to us to take care of.

Greg Dalton: You also work with this interfaith group that deals with congregations, mosques, there's not many areas where, you know, Christians and Muslims get along or agree these days but climate is one of them.

Gerald Durley: One of those issues. And in fact, when we went to Turkey not too long ago, Imam Plemon El-Amin in the Blue Mosque he was teaching from the Quran about climate change and Rabbi Ron Segal from Atlanta from the Temple there he and Peter Berg [ph] were teaching from the Quran. And then in emphasis I taught from the New Testament perspective and it’s interesting when we came back out of those three groups, and we got on a bus and people asked who are you all, we said we’re interfaith group. And some of the people that’s riding on the same bus we've got to get away from riding on the same bus as being shocking and ride on the same bus because we got common goals in this.

Greg Dalton: Reverend Gerald Durley is a retired Baptist pastor from Atlanta. I'm Greg Dalton. We’re talking about climate change and civil rights. Mystic, I’d like to ask you about Reverend Durley said earlier that climate is seen as something abstract and faraway. Music traditionally has played a very powerful role in movements, you know, anthems, et cetera. Tell us how you're trying to connect your music, your hip-hop music with getting people to get out and vote care about climate to reach them in a way as Reverend Durley says in the gut rather than parts per million, which is kind of abstract science.

Mystic: Right. I mean music is unifying, right. It’s not even just the hip-hop is unifying but hip-hop is unifying around the world and sometimes it's not explicitly saying it in the art, but it's the fact that through your art you’re helping to facilitate the space where people come together and they’re exchanging and then you can use your platform to kind of facilitate a conversation. As an artist, I’m not somebody who believes that like when I get up on stage to perform that I'm talking at you, right. As far as I'm concerned it's an exchange.

Greg Dalton: You’re not Bono, yeah.

Mystic: I can’t do it without. You know, I can’t do it without you. And it's an exchange of energy that happens. But so through that music look if you can get young folks to come out if you can get communities to come out, you can disseminate all kind of information. You can facilitate all kinds of conversations with the folks who come out. And so at the caucus like really bringing artists to some of them may have a much, you know, larger kind of level of success than I've had. If it’s somebody like T.I. or what have you, but when they start to use those platforms to talk about climate change and to talk about why they personally started to believe that it was important and that we needed to look at it, but also not separating that from like why we need to look at police brutality and why we need to look at broader systemic inequalities and other areas of social justice that young folks gravitate to that and they also see somebody who looks like them, right. Most hip-hop artists we are artist of color that has changed over time, and there are some more white artists. But it’s like you see somebody who looks like you who comes from your community who again is not using the parts per billion although I found that young people are very interested in that kind of information. As an educator it’s like when you put that there and they start to look at it, you can tell the difference in those numbers. It's not so abstract that they can't connect to it. So yeah the music brings the folks together and then the message spreads. But I think art is crucial in any movement, right. I think that like you can’t have a revolution without art. You can’t have a change without art. When we start to quash art, when we start to quash the role of artists using their platform and their voices to advocate and to amplify voices in the community, like when we start to quash it, we have a problem, right. I think that we’re turning into a society that we don't we never envisioned our society becoming. But if we remain quiet then those are the things that start to happen. So I'm like the more artists the better and the merrier and a hip-hop artist can get on a record and like say something that maybe you, people in this room or people listening on the podcast may not necessarily support. But if you have a conversation and you sit down with them you will find the people that you have these perceptions about are some of the brightest folks that you have talked to and again have these beautiful powerful ideas. And so yeah art, art and change I mean when have they not been connected. As somebody who studied anthropology when we look back, we look back and start to look at the reflections of what was happening within society and changes we can see it. And so art has always reflected that and as we’ve recorded audio I mean it's like and I’ll close up here but as long as people have been --

Gerald Durley: You’re not excited, are you?

Mystic: -- as long as people have been oppressed, people have been resisting. And as long as we have been challenging artist have been using our platforms and our art to contribute to that change and to pursue justice.

Gerald Durley: I just want to say in the faith community we call that a response, you know, call and response. We’re trying to call and response. And when you’re moving people you said, now you know what I’m talking about, amen, somebody.

Mystic: Right, amen.

Gerald Durley: See, see, that’s the response. You reach down because we’re interacting do you believe what I’m saying makes a lot of sense. I think somebody agrees with me. Am I right about it? You see that, that’s call and response. And that’s in the musical world, but in the faith world when we’re sitting there can you imagine selling heaven and nobody knows where it is. But we sell it and it gets down into the gut into the mind into the spirit. Then you get people that hook into it and Dr. King said once when we’re in Chicago in ‘66 or ’67. And some reporters had stopped him to talk to ask him some questions in Cicero, Illinois. And we were excited we had caught the momentum of the movement and we kept marching. And Dr. King said something that's always stayed with me when I think about movement development. He said “I cannot answer anymore of your questions. I've got to go catch my people.” If we're not catching our people we don't have a movement. So we gotta put it so they’re moving ahead, whether we get stifled get stopped we get tired and we quit. That’s the key, that’s why that young mayor excited me. He’s caught the movement and he's moving ahead of many of us. It’s call and response and you watch your audience and you pull in somebody sitting there. The person sitting there with those glasses are you with me tonight? Look at that. And that’s how you get and then pretty soon they take ownership. They take ownership. The environmentalists, the conservationists cannot keep this in their own little bailiwick, in their own silo. This is big, but if I don't believe I’m a part of it it’s just another passing fancy and will change in another few years this will pass by. But we've got a critical nexus moment this is a Kairos moment to pull all of that together. And I guess that's what excites me at this point.Announcer: You're listening to a conversation about civil rights and environmental justice. This is Climate One. You can check out our podcast at our website: climate one dot org. Greg Dalton will be back with his guests in just a moment.

Announcer: You’re listening to Climate One. Greg Dalton is talking about civil rights and environmental justice with Reverend Gerald Durley, pastor emeritus of Providence Missionary Baptist Church of Atlanta. Hip-hop artist and activist, Mystic. And Ingrid Brostrom, Assistant Director of Center on Race, Poverty & the Environment,

Here’s Greg.

Greg Dalton: I’d like to go to our lightning round and ask each of our guests. First, the true or false and then an association question. So first true or false and then I’ll mention a brief noun and ask them for the first thing that pops into your mind unfiltered. So here is some fun. So Mystic, true or false. Hip-hop has a misogyny problem?

Mystic: True.

Greg Dalton: Reverend Durley, environment is not a relevant term to many Americans?

Gerald Durley: True.

Greg Dalton: Ingrid Brostrom, environmental justice advocates sometimes obstructs progress by making the perfect the enemy of the good?

Ingrid Brostrom: False.

Greg Dalton: Also for Ingrid Brostrom. Some environmental groups help corporations green wash?

Ingrid Brostrom: I hope not.

Greg Dalton: Okay. Reverend Durley, true or false. Conservationists are often smart and dull as dirt?

Gerald Durley: Oh you had my quote.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: I got that from you, yeah.

Gerald Durley: Yeah, I thought so, yeah.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: I stole it but you can have it back.

Gerald Durley: Okay. Thank you. Thank you. That’s true. I mean you go to these meetings after meetings and at the end of the meeting they decide where they gonna meet again and discuss the same thing. You can educate anyone here about climate change and fracking and oceans and all this but it’s dull. And they're competing with the housewives of America and that's a tough act to follow.

Greg Dalton: I’m gonna mention the association part of our lightning round here at Climate One. I’m gonna mention a phrase or a noun and you will mention the first thing that comes to your mind. Mystic. Taking a knee.

Mystic: Tired of dying by being killed and fighting for justice. (0:46:08)

Greg Dalton: Ingrid Brostrom. Polar bears.

Ingrid Brostrom: Important. But so are people.

Greg Dalton: Mystic. Yes we can.

Mystic: Yes, we can. “Si, se puede,” right. Like yes, yes, yes. But I’m an educator, right. So I’m one of those let’s do yes create your environments for yes.

Greg Dalton: Reverend Durley. Tesla.

Gerald Durley: Wave of the future.

Greg Dalton: Mystic. Flint, Michigan.

Mystic: Black children matter and Flint, Michigan still doesn't have clean water without lead.

Greg Dalton: And neither do some schools in Oakland, California. Ingrid Brostrom. Fracking.

Ingrid Brostrom: It’s a dying industry that still doing a lot of harm.

Greg Dalton: Last one. Reverend Durley. Donald Trump.

Gerald Durley: A catalyst who will make America look at itself.

Greg Dalton: Let’s give them a round for getting through that. (0:48:00)

[Applause]

Greg Dalton: That’s one one the best Donald Trump answer I’ve heard.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: Mystic, let's talk about job creation, green jobs have been out there for quite a while. They haven't quite materialized to the extent that many people hoped when Van Jones first coined the term maybe first I heard it 10 years ago. So is there wealth creation opportunity happening or is that kind of been an elusive goal?

Mystic: In some ways I think it has been an elusive goal thus far, right. But I think that part of the path forward mandates that that must be a part of the approach moving forward. You can’t come to our communities and ask us to help solve a solution when other people are benefiting and not provide avenues where it's not asking for a handout, right. It's saying we are part of the solution. We too deserve to be part of this process and the solution.

Greg Dalton: Reverend Durley, you go to a lot of historically black colleges. What do you say to young people who are charting their career how to be part of this trend?

Gerald Durley: Yeah, I’ve had to shift, you know, I was Dean at two universities before one is school of medicine in Clark there in Atlanta and with the Hip Hop Caucus travel to 10 of the historically black college and universities. And would tell them now look at environmental engineering, don't talk about hopefully I can come up one day and put up solar panels and build windmills, own the company. Investing in the company, these are the kinds of things. This is what makes us come to this country move. So getting a new level of mentality and then the green just goes. Right now, when I went to Germany and different places, I didn’t see green jobs because there were many jobs. But when I went to the solar they had all this and it was only one person operating everything. Lot of people had lost their jobs when they came in. And so a lot of the people I’ve talked to, wait a minute, unless you really can be that one person who’s chosen to run the solar farm, you're out of work. So we’ve got to now as Mystic is saying with the business group, with the politician, see that we can move at another level. Now that's going to mean a new level of higher education to get into that. So then we’ve got to break down working with educators to understand that as we open the doors of opportunity to educate people so that they will be ready for this new influx of jobs. Otherwise it was the same old same old, a lot of people didn't get on the computer train early and they lost out to technology. The coal miners, they didn't get on it. So now the coal miners will never come back again. So now they've got to reboot themselves in another way. And I think that that's when the job really manifest themselves in reality.

Greg Dalton: Reverend Durley, a lot of environmental activism targets oil and fossil fuel companies as the villains and yet they sell a product that we all burn and use for our lifestyles everybody listening to this today use fossil fuels today. Are we complicit is it, you know, do we need to, you know, we complicit in this or is it simply that fossil fuel companies are evil and we've been passive victims of this?

Gerald Durley: Well certainly as long as we continue to burn fossil fuel and all this we are complicit. But the companies are going to do what they think that they can get away with to make money. I never thought growing up with outdoor toilet and poor, the oldest of eight, I said when I finally made enough money I was going to buy me a decent car and I didn't care what it meant. And I made enough money and I bought me a S550 Mercedes. And I said, now look at me I finally made it. And then as I start thinking about the environment and polluting all this, now I drive a hybrid. Now the company is now moving toward automated cars, autonomous driving car. They’re moving toward more electric cars. So we used to do a thing called boycott. If they don't do it, let’s not buy from that product. So I think when the public starts saying we’re not gonna buy all those large automobiles, we’re not gonna do that. Then I think that we’ll find the industry beginning to cut back on many of the atrocities that they've placed upon us. But as long as we continue to be you use the term complicit, why should they change.

Greg Dalton: We’re gonna go to our audience questions. Welcome to Climate One.

Female Participant: Hi. My name is Daisy Pestiline, question for Ingrid but others feel free to pipe in. Many people’s analysis of the failure to really achieve strong climate protections would be that the environmental movement just doesn't know how to get and take power. And I’ve heard and seen among both the activist community and the funding community in the last maybe five years more concerned about this and trying to figure out how we build infrastructure to actually support the movement. What would you say are some of the pieces that are missing right now that we need to actually be a powerful movement that can exert political influence and when?

Ingrid Brostrom: I mean I think the first piece is alignment. There is a tremendous amount of differences of opinion in and amongst the environmental justice movement. And so until we get on the same page, recognizing the magnitude of the problem it's gonna be hard to move forward. I think another criticism of the more of the mainstream environmental movement is its focus on litigation rather than power building. You know, the environmental movement helped create the laws that we are relying today, the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act and it was designed to be more of an elitist movement with the ability to understand these laws, exclude real broad public participation, but then the ability to go to court. And so we need to kind of dismantle that and recognize absolutely that until we change the power dynamics that have led to the situation we are in today we’re not gonna win. And that's why, you know, a lot of the environmental justice organizations focused very locally on building power as one of the very key things that we do. And that, you know, power is that change. And so, yes, I definitely think that we need to move to more organizing, more voter drives, more policy work and definitely that alignment piece.

Greg Dalton: Next question. Welcome.

Female Participant: Reverend Durley, we often think of climate change as an economic issue and a public health issue but it seems like we don’t pay enough attention to the mental health aspect of it. As we deal with more devastating, you know, fires and natural disasters, loss of life, property, jobs. It’s hard for communities to cope with that. Are there any lessons from your training as a psychologist and also as a reverend as a pastor in how we can make sure that our communities are resilient and can cope with the mental health stressors of climate change?

Gerald Durley: When I went to Ferguson, Illinois after the shooting have taken place and several other shootings and the environment -- so we combined two kinds of environment. One is just the racist kind of environment that's there in terms of education in terms of unemployment those kinds of things. And then if you take anybody, anyone in this room and you put them into a confined area and the temperature, I often say where and during the winter we heat the outside and during the summer we cool the outside because the houses are not insulated and so you’ve got people that's like that. So we have to deal with the psychological kinds of pressures the mental pressure that occurs. So when we talk about what this really means to you in terms of depression which leads towards a suicide. When we talk about the gap between the images that are being portrayed and the reality of what we face from a psychological mental aspect, that's what we have to deal with and then deal with the loss. Like when I was over in Burke County a few weeks ago they said to me, so a few children are born deformed, so a few people die. At least we're working. So I had to look at what does that mean. And so some of them turned on me so I had to sit back and say that's right, you do have jobs but what is the expense of your doing that. So then we had to look at what do I give up. Do I give up making some money here or do I give up the well-being of this community and we work with this company to make it whole.

Greg Dalton: Next question. Welcome.

Female Participant: Hi, my name is Mary and my question is for all three of you. The connection between the environment and social justice isn’t apparent to all people. So what has been a challenge that you’ve encountered in communicating the connection between sustainability and social justice and how did you overcome it?

Greg Dalton: Reverend Durley, have you encountered people in the South or elsewhere who just say I don’t get the connection.

Gerald Durley: Between.

Greg Dalton: Sustainability and other social justice issues. Whether it’s incarceration or whatever it might be.

Gerald Durley: No. I don't think -- and the reason and I think what Mystic was saying is that the connection is not made because when you are involved with five or six other priorities you don't make the connection between climate. Climate is just, it’s warm out here today or there are torrential rains. But it doesn't connect to poor education, it doesn't connect to those and that's what we're doing now as I said earlier, organizing. I remember when in 1960 many black people say, why are we fighting to vote, we can make it, we’ve got our own businesses. They didn't realize that that was a constitutional right that it already been there. When we talk about affirmative action and all the fear, we've got to understand that affirmative action was really laws that had already been on the books. And a congressman got up one day and said let's affirm those actions. Let's do what was right. So consequently when people don't know ignorance breeds fear and fear breeds a kind of constipation of action. So right now you got people that are saying well maybe, maybe not. But when we can bring them to a level of awareness I don't care how poor a family might be or how destitute. When they hear justice issues when they know this is just not right and they get it, then they become a part of how do we bring forth this change. And I think we’re getting to that point now in America and what people are beginning to realize that now this is really destroying us mentally, physically, financially, every kind of way. And I’m pleased that this is it’s coming to that point. I mean I’m getting to that point now and I can articulate it even much more now because as it’s been said, climate change is not a hoax. It is real. And it’s not real for the future, it’s real for right now. And that's what's going to really generate the kind of gut feelings to make people rally around now. When we went in New York 400,000 people in the street and what the women did after the election out in the street that’s what it started to happen now. And I guess it’s infectious now.

Greg Dalton: We have to end but I wanna end by asking each of you quickly. What gives you hope, Ingrid. What gives you hope?

Ingrid Brostrom: Actually it’s the mayor of Arvin, Jose Gurrola is somebody that a lot of our groups help support and got him elected in the reddest part of the state, the most conservative part of the state, the most oil dominated part of the state. And we have an anti-fracking mayor and that gives me hope.

Greg Dalton: Mystic.

Mystic: Children and youth are my hope, my passion. On the hardest day whatever happens in the world if I get to spend time with children, I am reminded of why we do this work. Why the work is necessary, why it is mandatory and just like especially when you’re with the kindergartners and the first and the second graders like you know, they give you hugs and they’ve just got these big eyes and they think some things are just so hard about life, but it's like because their friend didn't share their yogurt with them, right. And so it just reminds me they are my hope.

Greg Dalton: Reverend Durley, what gives you hope?

Gerald Durley: I guess my hope -- I’m 75 years old now. And at my age to think back in 1963, August 28th the front line when we were marching there in Washington and we saw all colors, all faith. And I see a sense of that occurring again now 50 something years later where people are coming together across faith lines, across racial lines, across the sexual gender lines, across colors. And I see that and I see the young people who with the level of social media they’re much more open to discuss my grandson and the young people are doing this, much more so that then than we did. And I think that that gives me a lot of hope to see them that they're open up and the fear factor is not in them. I think that they would take the leadership to help those of us who are somewhat reticent in breaking down these barriers. And I think that gives me hope.

Announcer: Greg Dalton has been talking about climate change and civil rights with Reverend Gerald Durley, pastor emeritus of Providence Missionary Baptist Church of Atlanta. Mandolyn Wind Ludlum, better known as hip-hop artist and activist Mystic. And Ingrid Brostrom, Assistant Director of Center on Race, Poverty & the Environment.

To hear all our Climate One conversations, subscribe to our podcast at our website: climateone.org, where you’ll also find photos, video clips and more.

Please join us next time for another conversation about America’s energy, economy, and environment.

[Applause]

Greg Dalton: Climate One is a special project of The Commonwealth Club of California. Kelli Pennington directs our audience engagement. Carlos Manuel is the producer. The audio engineer is William Blum. Anny Celsi and Devon Strolovitch are the editors. I’m Greg Dalton the Executive Producer and Host. The Commonwealth Club CEO is Dr. Gloria Duffy.

Climate One is presented in association with KQED Public Radio.