When Words Aren’t Enough: The Visual Climate Story

Guests

Céline Cousteau

Davis Guggenheim

Cristina Mittermeier

Summary

While IPCC risk assessments and emission projections can help us understand climate change, they don’t exactly inspire the imagination or provoke a personal response to the crisis. But a growing league of storytellers is using photographs, films and the human experience to breathe life into the cerebral science of climate change and conservation. So how can films, photographs, and the human experience convey the urgency of the climate story?

“15 years ago we needed to convince people that it was real,” notes director and producer Davis Guggenheim, “and then we need to convince people that humans are causing it. And then you want to convince people that this is the most urgent story of our time.”

Guggenheim’s documentaries include He Named Me Malala, Waiting for Superman, and a certain Academy award-winning film with former Vice-President Al Gore. Over the years he’s learned that good climate storytelling requires a delicate balance between a compelling character and a path to action.

“We always thought the An Inconvenient Truth was a redemption story about a politician who lost an election,” he says, “and it was his mission in life to tell this truth that he knew.”

Sometimes the compelling character in a climate narrative is the filmmaker herself. In Tribes on the Edge, a new documentary that explores the threats to the land, rights, and health of the Indigenous Peoples of the Javari Valley in the Brazilian Amazon, explorer and filmmaker Céline Cousteau reluctantly made herself part of the story.

“I did place myself in front of the camera so that I would create a bridge,” Cousteau says, “so that the audience would follow me as somebody perhaps more familiar, more accessible, the neighbor, and follow me into this adventure.”

Other visual artists, like photographer Cristina Mittermeier, try to let the images speak for themselves.

“I don't like photographing indigenous people as if they were encapsulated in the past in a romanticized way that no longer exist,” she says, “they live and walk amongst us and they look like us.”

Whatever their methods, these storytellers share a goal trying to create a more equitable relationship with nature through images and sound.

“Do not ever forget that one of your main focus and goals is to shift consciousness,” explains Céline Cousteau, “and you may never know exactly what your films or stories have done, but you need to believe in what you're doing.”

RELATED LINKS:

Full Transcript

Greg: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. [pause] Risk assessments and emissions projections don’t exactly make us feel the climate emergency.

Davis Guggenheim: 10 years ago or 15 years ago we needed to convince people that it was real. And then we need to convince people that humans are causing it. And then you wanna convince people that this is the most urgent story of our time.

Greg: A growing number of storytellers are using films, photographs, and the human experience to breathe life into the climate crisis.

Céline Cousteau: It's not the blockbuster, big-splash film. It's truth, it’s intimacy. And some of it is ugly and some of it is beautiful.

Greg: So how can images and sounds inspire a sustained climate response? Lack of climate action is not because there is a lack of information.

Cristina Mittermeier: How do you provide a call to action to people that are watching your film that's tangible and in the moment? How do we use this to rally for protection?

Greg: When Words Aren’t Enough. Up next on Climate One.

Greg: How can films, photographs, and the human experience convey the urgency of the climate story? Climate One conversations feature all aspects of the climate emergency: the individual and the systemic, the exciting and the scary, people who are in power and disempowered. I’m Greg Dalton.

Davis Guggenheim: We always thought the An Inconvenient Truth was a redemption story about a politician who lost an election, and it was his mission in life to tell this truth that he knew.

Greg: Davis Guggenheim is a writer, director and producer. His documentaries include He Named Me Malala, Waiting for Superman, and a certain Academy award-winning film with former Vice-President Al Gore. As Director of An Inconvenient Truth, Guggenheim learned that good climate storytelling requires a delicate balance, between a compelling character and a path to action.

Cristina Mittermeier: As artists, all we can do is hope that you can make people stop for one moment and think.

Greg: Cristina Mittermeier [MI-der-MY-er] is a photographer, conservationist, and marine biologist. She founded the nonprofit SeaLegacy with her partner, photographer Paul Nicklen. In her photographs, Cristina tries to avoid romanticizing the indigenous people she depicts.

Céline Cousteau: I felt that I had to deserve the honor to tell the story. And part of the trial and error was testing my conviction that I could do it in a way that honored the voices of the people I work for, the indigenous people in the film.

Greg: Céline Cousteau is a filmmaker and explorer, and the granddaughter of pioneering ocean adventurer Jacques Cousteau. Her new documentary, Tribes on the Edge, bears witness to indigenous communities in the Amazon who are fighting for survival amid deforestation, oil extraction, and gold-mining. The project began with an email a few years ago from a man she’d met at a conference in the Amazon named Beto.

Céline Cousteau: Beto is from the Marubo tribe in the Vale do Javari indigenous territory in the Brazilian Amazon. I was there in 2007 filming a conference of the contacted indigenous people of that territory as part of a film called Return to the Amazon as we were going back to places my grandfather had been to in the early 80s. And when I was there, I bore witness to the stories of critical health issues hepatitis, malaria being two of them now COVID is added on top of that that the indigenous people have been facing for decades. Started with the colonizers in the 16th-century. And I was heartbroken, I mean, we, you know, I’m a filmmaker and I tell stories but I also watch stories and to be in the midst of it impacted me in a tremendous way and I wanted to do more than just do that one film. It was years later that Beto sent me an email and he said I want you to tell my people story I want the world to know we exist and we want to live. And there's really, there’s no other answer but yes and yes I rearranged my life to make this part of it, that was in 2010. So, it's now 11 years later and the film just came out in February.

Greg Dalton: Congratulations on that. We’ll get into indigenous people a little bit later. Céline, your family synonymous with oceans are you more passionate and what were you doing, you were in the forest, which maybe an unusual place for a Cousteau, maybe not, but are you more passionate about sea life or people?

Céline Cousteau: I'm passionate about the human story at the center of the environmental story, no matter what ecosystem. I'm just as comfortable being thrown in the ocean as I am hiking in the jungle, but I like to think I have a fin on one foot and hiking boot on the other ready to go. I think the important part is really making the human nature connection, no matter where it happens.

Greg Dalton: Davis Guggenheim, your dad won four Academy Awards for making documentary films, including one for remembrance of Robert F Kennedy shortly after his assassination were shown at the Democratic national convention. You followed on your dad's footsteps and in the 1980s when you were in college, he wanted to make a documentary about apartheid. What advice did your dad give you then?

Davis Guggenheim: Well I told him I was very excited because I admired my dad, he was a wonderful man and a great filmmaker. And I said, I’m gonna make this film about apartheid. And he said, well, who’s it about? I go, it’s not about people it’s about this big thing and it’s this movement. And he’s like, well, if you don’t have a person, you’re following that’s really hard as a storyteller. And I’ve kept that with me. He always said that people when they’re watching a movie care about people. And whenever I’ve done that it’s works up pretty well. Whenever I’ve forgotten that my films get a little too far off and a little bit hard to identify with. I think I’m always trying to find stories that are universal that can bring more people together. And if you can humanize almost anybody, there’s a few people who you can humanize. But that really, I think is a great thing. And I keep my father on my shoulder every day at work.

Greg Dalton: In connection with humans and natures a theme and all of your work and a lot of documentary films about climate change I think they lose that human element. They’re about issues and systems. And Cristina Mittermeier, you say that we want to imagine wild animals accepting us into their world. A world where humans evolve for thousands of years. How do you think about that when you are photographing wild animals in their habitat?

Cristina Mittermeier: It’s an interesting thing. I enjoy so much your comments Davis and Céline because it is true, it's about the human experience as a citizen of this planet. Most people are for whatever reason not in a position to experience that in the way that so many of us have with a fin on one foot and a hike boot on the other. And a lot of people are afraid frankly, you know, and I think we have raised an entire generation that is afraid of getting dirty or getting sick or whatever and they don't go to nature. So, when you can create images that allow people to imagine themselves interacting with nature, especially with animals. I think people just crave that you know the friendship with an octopus can you imagine?

Greg Dalton: Yeah, that's quite a film. Céline Cousteau, you talk about swimming near a humpback whale and it looking you in the eye and acknowledging you. What is it like to come eye to eye with a whale?

Céline Cousteau: You feel really small. And I don't mean just in size I mean in importance. Because we are, we’re tiny, I mean human beings are tiny on this planet, we’re just really numerous and impactful, which can be negative or positive. But that moment that a humpback whale looked at me I just kind of stopped in the water and just felt my existence. It's hard to describe. And touching on what Cristina says a lot of people either are afraid to or don't have the opportunity to get in nature, but there's so many there are so many moments in nature that really touch on the heart of what we are in this bigger system. That we are just one species, amongst others. And that moment eye to eye with a humpback whale for me was just a stark example of it and a privileged one.

Greg Dalton: Cristina Mittermeier, you have a million and a half followers on Instagram which is pretty darn big and yet you also say that makes you feel small. But are we supposed to feel small in nature or is feeling small in the face of climate change?

Cristina Mittermeier: I think we’re an arrogant species, you know. I think it humbles us and makes us really uncomfortable when we feel small and insignificant. For me, the act of stepping into nature is always a pass it contracts where you become part of the food chain you become part of a system that you don't control. I like that feeling. But I think humans especially you know the culture that we have created for ourselves over the last 100 to 150 years is one of supremacy over nature. And I mean I think many of us that's what we’re trying to change with our films on our narratives, you know, try to create a more equitable relationship with nature.

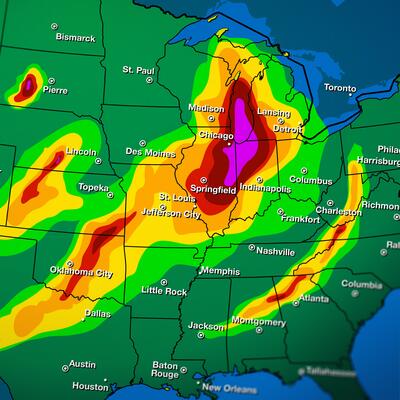

Greg Dalton: I lived in China in the early 80s, late 80s after college. And I remembered sort of the classical Chinese paintings will always show these huge mountains and show the humans as, you know, very tiny, relative to nature which was I thought was like odd to me. I hadn't seen that before going to live in China. Davis Guggenheim, the poster for An Inconvenient Truth features hurricane coming out of a smokestack. What are the dominant images you think of that define the climate narrative?

Davis Guggenheim: Well, it’s interesting to know that poster is presented to me by Paramount Studio. I said this is sensationalistic it’s over the top. And the trailer is the scariest movie you’ll ever see. And I was really upset about it I mean I went to the mat saying this is a terrible way to market this film. It turned out to be a really good way to market this film. So, I learned a lot. When I made the film, I wanted the tone of it to be moderate and not political and to reach as far to the middle and even to the right if I could. So, the answer for me is or the lesson for me is that marketing of film is very different than making a film and what your story is. But there’s a lot of, I have a lot of answers to that question but I think for that movie the images that seem to resonate with people were the polar bear swimming in the water and putting its paw up on a piece of ice that was too small to find firm ground and swimming away back into the endless ocean. You can hear people gasp in every screening of that movie. And then Al Gore was really smart about at that point reinforcing in almost every slide the CO2 marching up and how it would go up how you visualized it, it sort of imprinted. But that's more than 10 years ago and since the challenges are very different. Back then it was like is it real and do we understand it. I think now the challenge is that further in this conversation but now it’s about now that a lot of people believe it's real and that we’re causing it, now what do we do and how do we activate people? So, I think the images might have to change.

Greg Dalton: Cristina Mittermeier, polar bears are probably the most iconic image associated with climate change. Your partner photographer Paul Nicklen made a video of a starving polar bear in the Canadian Arctic in 2017 around Baffin Island. I think I was there around that time. You were there as well. The National Geographic video went viral and reportedly was seen more than 2 billion times. Your photograph I think was the top 10 for the year. Looking back now, what do you see as a lasting impact of that weak, hungry, sad polar bear limping around in the final hours of its life?

Cristina Mittermeier: Yeah, I think Davis and Céline would agree with me that it's never the one moment you know. I remember Davis when the Inconvenient Truth came out, the book, was a sense of relief. And you know I felt almost like a polar bear, you know, because for those of us who have made a living trying to convey with science with images you know what's happening and the gravity of the situation. And you know the denial arguments were so exhausting that when Inconvenient Truth came out it was really a moment that it all turned out. And yet it didn’t last, right, I mean people move on. And so, we are continuously striving, Greg, to make those iconic moments. And as artists, all we can do is hope that you can make people stop for one moment and think. And the starving polar bear was that. We had no idea that it was gonna cause such a stir, but yes, it went viral. And so many things were revealed just how emotionally invested people are in the welfare of animals. How upset they get when action is not taken. But we also got a really deep look at the enormous amount of people that are still in denial at the machinery of communications behind the continual denial of the problem and how well-funded they are. You know, we started getting a glimpse at all these think tanks that are out there putting out wrong information. The one thing I kept thinking, Greg, was they’re investing so much money in perpetuating this situation on the lie. How much money are we investing? Because as a filmmaker as a photographer it’s always so hard to get the funding to go out there to tell more stories. So, are we investing at the same scale of the solution? And this is the question for all the donors out there. But yeah, the starving polar bear for me it's just a page in the book I hope to make many more images that continue to steer our emotions into action.

Greg: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation about climate storytelling employing images and sound. Coming up, showing humility and earning trust as a storyteller.

Davis Guggenheim: It was awkward at first, it was genuinely awkward. They would often touch my hair to see if it was real, they thought I was the oddest person in the world and they laughed at me. And that was a good sign.

Greg: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton, and we’re talking about visual climate storytelling with Academy award-winning director and producer Davis Guggenheim; Photographer and marine biologist Cristina Mittermeier; and explorer and filmmaker Céline Cousteau. Her new documentary, Tribes on the Edge, explores the threats to the land, rights, and health of the Indigenous Peoples of the Javari Valley in the Brazilian Amazon.

[Tribes on the Edge clip]

Greg: Despite not wanting to make herself part of the story, Céline found that her presence in the film was one way to humanize a group of people that affluent viewers in rich northern countries, might otherwise have difficulty relating to.

Céline Cousteau: I did place myself in front of the camera so that I would create a bridge. So that the audience would follow me as somebody perhaps more familiar more accessible the neighbor and follow me into this adventure. And through me meet the people that affected my life. I also chose to be more vulnerable than perhaps I would've wanted. Because the story wasn't about me, but I chose to actually film inside my home. I'm fiercely protective of my personal space, but I thought it was important if I asked the audience to stretch their ability to create a connection with people, they don't know that I had to let them in a little bit more than I otherwise would have. So, that's one way. Another one is that I didn't craft any of the scenes. I didn't ask any of the indigenous people no matter which village or which tribe we were visiting I didn’t ask them to put together ceremony or ritual or ask them to go hunt. We really just followed the ebb and flow of their life and sometimes that means we may have missed out on the absolute beauty shot that would've made you know the scene in the film. But I think it showed something much more intimate because it was authentic. And I think that at the end of the day that shows in the film. It's not the blockbuster big splash film. It's truth it’s intimacy. And some of it is ugly and some of it is beautiful.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, a lot of it is beautiful and you do see your son bounding on the stairs in your home before you set off. Connect for us the resources the sort of the why should I care question. We hear a lot about the Amazon is this faraway place for someone listening to this in Canada, Europe, North America. How are we connected our lives to the people you portray in Brazil and in the Amazon?

Céline Cousteau: A lot of ways. One very simple one. If you enjoy breathing, you're connected to the Amazon and its people. About 20% of our oxygen comes from the Amazon rainforest and where there are indigenous people where there is protected indigenous land there's no deforestation. There’s actually less deforestation on indigenous land than there is on conservation land. So, the presence of people in this case creates an additional barrier to protect the territory. The Javari territory in particular is deemed irreplaceable in terms of biodiversity by the IUCN, the International Union for Conservation of Nature. And one of the projects we’re hoping to do is discover that biodiversity. And that biodiversity is something we all count on. If you think about your pharmaceuticals, most of our pharmaceuticals have their roots in nature. If there is undiscovered biodiversity that’s the potential for our future medicine. And there is no better example than what the world is going through today when we think of something that could impact all of us. And then there's just all the products we use very simply put; I mean if you know if we have gold in any of our jewelry if we have hardwood in any of our furniture. A lot of those things come from places like that. And we may not know that they are harvested illegally, but it's important to understand that there are a lot of these products that come from extraction that is unsustainable or impacting indigenous lives.

Greg Dalton: Cristina Mittermeier, you also work and photograph number of indigenous people some really beautiful photographs. Who is Will George and how do you give him his power back by taking his photograph?

Cristina Mittermeier: Will George is a member of the Tsleil-Waututh First Nation in British Columbia, a community that has been impacted by the construction of oil pipelines through their territory. And they have been fighting the construction of another pipeline coming in from the interior from Alberta to carry crude to the coast of British Columbia, which then gets carried to China and then gets for refining and then gets brought back into Canada. And Will George and his tribe members have been standing up to the construction of this pipeline have been disrupting have been protesting and they invited me to come and spend the day with them and photograph them. They built a beautiful what they called a watch house where people could come in and have ceremony and spend time together. And like Céline, I don't like photographing indigenous people as if they were encapsulated in the past in a romanticized way that no longer exist. They live and walk amongst us and they look like us. And so, does Will, you know, Will works in the Home Depot. But he brought in his family’s headdress and he put it on and I asked him I said, how angry are you, you know, the infractions that this government imposes on indigenous people, not just his tribe but so many of them. And he, you know, express his anger and when I showed him the photograph and I don't know if this has happened to you Céline, but for communities like the Tsleil-Waututh and so many others in British Columbia they were forbidden for generations to wear their traditional costume to speak their language. They were, you know, they were taken to residential schools where they were taught not to speak their language. Anyway, when you show them a photograph of themselves bearing their family's ancestral regalia you return something to them. And part of it is the power and part of it is the pride and part of it is the understanding of the place they have in this fight and to protect our planet.

Greg Dalton: One photo of yours, Cristina, that I really like is a young indigenous person sitting on rocks near the ocean with a fishing net in their hands, face paint headdress and Chuck Taylor sneakers. Which just shows like this is a real modern teenage, probably a teenager. So, tell us about that photo and what is, yeah.

Cristina Mittermeier: That is the northern tip of Vancouver Island a community called Alert Bay and the Namgis people live there. And I was invited and are so honored because the potlatch is something that has returned now that indigenous Canadians have more opportunity to express their culture. So, I was invited to a potlatch and I was surprised by so many young people who are now learning the language and the songs and the dances. And I noticed this girl because she was part of that potlatch her passionate dance. But I was not allowed to photograph in the big house so I looked her up on Facebook and I talked to her and I said, you know, I would love to photograph you. And so, we set up a date on the beach and this is how she showed up.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, it’s great. Davis Guggenheim, you had never met a Muslim family before you made a film about one of the most famous Muslims in the world, Malala. How did you approach that going into that culture what kind of humility did you have to summon and how did you go about getting so close to one of the most famous teenagers in the world?

Davis Guggenheim: It’s interesting it’s a great question. She was 15 1/2 and was still covering from, I mean she woke up in a UK hospital not knowing what the UK was. And I approached it the same way I approach everything which is an attempted humility and openness a vulnerability. I think vulnerability is a really important thing like are you and -- but this family, y Malala, her mother Thorpekai, her father is Ziauddin and her brothers Khushal and Atal. But I maybe was introduced to a few Muslims in my life but never welcomed into a home. And it was awkward at first, it was generally awkward. But within a few days we all fell in love with each other. They would often touch my hair to see if it was real, they thought I was the oddest person in the world and they laughed at me. And that was a good sign. But I’m sure that Cristina and Céline feel the same way where you, you know, it’s always different with everybody. But the most important thing is you earn trust slowly and over time and with humility and being vulnerable.

Cristina Mittermeier: The other interesting thing for those of us who work with the people that are not from the Western world is that we’re all on social media. You know, I've made friends with almost everybody that I photographed even in remote indigenous communities in the Amazon and stayed in touch with them through WhatsApp or Facebook. And so, it gives you the opportunity when you get an email or a text from somebody like Will George saying they're taking me to jail I would love to use that photograph, you know, to rally for my defense. It gives you just such an honor to be able to continue to help.

Greg Dalton: We’re talking about climate storytelling with Céline Cousteau, Cristina Mittermeier and Davis Guggenheim. I’m Greg Dalton. We’re recording this show with a live audience. And one question from a listener, Lisa. Are there other films in the pipeline like My Octopus Teacher which was about love and connection and a deep knowing of place? And this is, I think a lot of people saw this film. When my wife and I watch it, people were just gushing about it, it was amazing. So, Cristina tell us about the film a little bit and how you reacted to seeing it.

Cristina Mittermeier: I mean first of all, Craig Foster, the filmmaker is a dear friend and his wife Swati and I have been fellow warriors in many conservation battles. And so, I know that they were making this film and the part that they struggled and this is where I would love to get Davis’ and Céline’s thoughts was how do you provide a call to action to people that are watching your film that's tangible and in the moment. And the Octopus Teacher was yes of course about the relationship of this man with his backyard this beautiful kelp forest and the octopus. But the deeper intention that they had was, you know, how do we use this to rally for protection. There is a devastating octopus fishery, all these ropes have entangled so many whales and it slowly causing the demise. And that's where I want us to go as an artistic filmmaking community to being able to use the social media and the technology platforms that we have to build a larger community and the call to action that people can continue taking.

Greg Dalton: And Céline Cousteau, it seems like one thing that, you know, there’s a one-to-one relationship in that film. It's very deep and beautiful and that’s different than a lot of nature documentaries, etc. where you see a charismatic mega fauna briefly and then it moves on. But there is like, I mean there is intimacy between this exotic creature and this man. So, tell us your thoughts about My Octopus Teacher and what it illustrates and what’s so powerful in there.

Céline Cousteau: Oh, I think what works really well there was that it was a relationship. It doesn't matter if it was intra-species it was a relationship. And you inherently understood that and you understood the love that was created the admiration the piece that was brought to him by having this contact with nature. The reverence he had for the animal the understanding of the animal allowed him to be in its realm and its world. The people that I have heard from who aren’t in our circles I’ll say of either filmmaking or nature or environmental protection, we’re in all of it and they all felt it. So, to kind of answer the question, Cristina as well of like how do we get people to motivate to action. I think part of what we do in storytelling is intangible and that's I know for me really difficult because we share a story with the world. We don't really know what they're going to do with it, and we don't necessarily at the end of the film just want to say here's your to do list. Because part of it is about shifting consciousness and I think that that’s something that's, I know it's hard for me but I have a filmmaker friend who years ago said this to me. He says do not ever forget that one of your main focus and goals is to shift consciousness and you may never know exactly what your films or stories have done, but you need to believe in what you're doing. So, there's no easy answer of, you know, putting a little PSA at the end of your film kind of breaks the magic of that love between this human and this animal. I think people will follow up and they do in their own ways. I know some people who are not eating octopus anymore because of the film. And if that's all that was done, I'm applauding it.

Greg Dalton: Davis Guggenheim, the documentary films now are platforms for action participant media and other groups are trying to use them to mobilize people, An Inconvenient Truth, awaken the generation. Your thoughts on My Octopus Teacher, in fact you noted earlier when we talked that the man seem to have a closer relationship with the octopus than his own son.

Davis Guggenheim: Yeah, I don't know I mean they seem like a lovely family. And that was more of a question not knowing anything. But I like what Céline was saying. I think the filmmaker’s job first is to tell a story. And I was like to think of the movies I make it’s like what is the story outside of the issue that you’re making. We always thought the An Inconvenient Truth was a redemption story about a politician who lost an election. It was his mission in life to tell this truth that he knew. And of course, the movie had tons of charts and graphs and all those other stuffs. But at the core heart of it you identified with him. I think what’s great about Octopus Teacher it’s a love story. And like every great love story, love stories are always, the formula for love stories are the simplest of formulas which is, you know, these two, usually people, but like these two organisms, you know, and they want to be together desperately. It could be Doctor Zhivago or could be a teen flick. But a great love story are the obstacles that get in their way. They come closer and then the obstacles pull them apart. They get closer and the obstacles pull them apart. And, you know, what’s beautiful about that movie is it just works as a love story first. And I think that’s our job first is to tell that story that cast a spell on you. And sometimes not always, I think sometimes the message and it happens in my movies a lot, the message breaks that spell. And so, you have to figure out a way to, and I don’t want to go into them, but we had a great lesson we learn when we made Inconvenient Truth where we had no prescription and we show people the film and they’re like, what are we supposed to do? And so, we learned at the end to put things you can do in the end credits and that was a great breakthrough for us. So, you’re constantly trying because a lot of my films are about issues but how do you tell that story and keep the spell from breaking. And then give people what they want once you cast a spell and they’re asking for it.

Greg Dalton: So, Cristina that gets to, you know, beauty, you know, someone told me the term, you know, apocalyptic subline. The imagery that’s used in climate is the disappearing beauty. A lot of it is very depressing. A lot of the climate story is very depressing. Here's melting glaciers melting this, you know, dying trees, death everywhere. How do you wrestle with the emotional balance, you know, you want to find inspirational beauty, but there is also loss and sadness in that beauty?

Cristina Mittermeier: You know, because storytelling is so ingrained into who we are as humans. We’re not the first ones to come up with how to tell the stories. And for me, you know, the great storytellers like Rev. Martin Luther King, you know, he didn't start his speech by telling us I have a nightmare. He told us about his dream and this vision that he had for a better you know more equitable society. And then he reminded us in the same speech of the perils and the pits and all the hard work had to make it better. And then he reminded us again, you know, if we do the work this is where we'll go. And I think a good narration takes you through those emotional valleys and hills because it's just human.

Greg: You're listening to a conversation about climate storytelling using image and sound. This is Climate One. Coming up, overcoming despair and storytelling exhaustion.

Céline Cousteau: When somebody in the audience asked Beto of the Marubo tribe what can they do? Beto says now that you’ve seen my story, keep telling the story because it becomes yours. And I think that that’s something that we can ask our audiences to do.

Greg: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. We’re talking about the visual dimensions of climate storytelling, with filmmaker and explorer Céline Cousteau; Photographer, and conservationist Cristina Mittermeier; and Academy Award winning director and producer Davis Guggenheim. Our ability to deeply absorb images of nature, depends on how our brain receives them. Dr. Laura Sewall [SOO-ull] has taught eco-psychology and environmental perception, at Prescott and Bates Colleges. We asked her to help us understand how visual media connects us with the natural world.

[Start Playback]

Laura Sewall: When we’re sort of gazing into the natural world or in it, we’re not cognitively trying to do very much. Whereas, when we look at facts or graphs or lists of data or reading books about climate science, takes a lot of cognitive effort. And we, for the most part don't like to work too hard cognitively. It takes a lot of metabolic energy. We also always wanted to use cognitive ease. So, if there is imagery that is easy to access and this got these wonderful natural associations, we’re going to absorb it more readily. Let’s take advertising using nature to seduce us into buying a Jeep that will then tear up the terrain. There is no mistake there. There is an understanding that the associations are activated and we’re feeling all sorts of pleasurable stuff and we want that Jeep too. But there's a lot of good work out there. Some of those Patagonia and North Face short story adventure films. They've got great footage they show the reasons to be engaged the wonder of the world. And in the background is the message of this being in peril. This adventure something as this possibility. So, here's great human potential great experience and just remember it might be lost, but you've got all sorts of ability.

[End Playback]

Greg Dalton: That was Dr. Laura Sewall, author of Sight and Sensibility: The Ecopsychology of Perception. Davis Guggenheim, you're interested in how the human brain perceives climate threats. How conscious are you of how nature is being used in the video and photographic advertisements that you see on screen?

Davis Guggenheim: I'm just at the beginning of research on another movie about what I simplistically call the psychology of climate change, I’m not really thinking so much about imagery. I’m thinking about how this heavy, heavy sense of catastrophe plays on all of us as we live our lives, especially on my own children and everyone’s children. I think that's another angle into this problem.

Greg Dalton: Tell us about your son's 21st birthday. You bought him his first case of beer and it ended up in a surprising conversation about climate change.

Davis Guggenheim: Yeah, so this is a couple of years ago he was in college his junior year. And my wife and I said can we visit you on your 21st birthday? And he said, sure. And so, it’s a big really fun night with all his roommates like eight of his friends. Little mismatched tables pushed together and beer and take-out Chinese food. And it was just the most fun I've had in a long time, still it’s one of my best memories ever. But about 2 o'clock in the morning I asked one of his best friends. I said, well, how many children do you think you’ll have? He’s my son’s friend and he said, oh, I wouldn’t bring children into this world. And then we went down the line and none of my son’s friends said they would bring children to this world including my son. And the striking thing was that but was also the fact that very few of them talk about climate change. And so, they feel this great sense of catastrophe and yet they don't deal with it on a day-to-day basis. I’m interested in how they carried that, and perhaps if there's a way to sort of unlock that and understand that then maybe that’s another angle into breaking through in this complex issue.

Cristina Mittermeier: Can I say something about that, Greg, because I do have children of the same age and none of them wanna have children either, which is no surprise. But they live very close to the issue through us, right, through our passion. I noticed that young people feel in general so overwhelmed and disempowered and you know to deal with this a lot. So, I wanted to find a way of giving them an opportunity to be connected that was not a heavy lift emotionally or otherwise. So, we built a platform where you can tell short stories, with very contained, but they’re emotional and they’re beautiful. And at the end of every story, there's something that you can do right then and there. It can be sign a petition or tweet to a prime minister or donate five dollars to community. That sense of I've done my part is really important than, so stories you can tell people you know this is what you contributed to. When they hear that if they’re part of a bigger community making a difference, I think it starts lifting that sense of foreboding doom.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, it’s very deep it’s one of the things that’s mobilize climate action lately as young people been putting pressure. And there’s a certain resignation and I have kids who are in early 20s, late teens and really worry about the burden and often don't honestly talk to them a lot about it because I don’t want dad’s job to be, you know, a burden on them. We have a question from one person watching on the livestream. We’re recording this show with a live audience and one question from a listener, Lori asked, “Can we make a movie about the Amazon being burned for grazing lands and growing palm oil and focus on the companies behind that so they can be boycotted and shamed into stopping what they are doing?” Céline Cousteau, is that your next film?

Céline Cousteau: Oh, my next film, I have to first openly admit that I have a little bit of storytelling exhaustion, which is hard to admit on a discussion about storytelling.

Cristina Mittermeier: It’ll go away, Céline, you’ll be fine.

Céline Cousteau: I feel like I just got through this one and the next one, yeah. There will of course there will be a next one I mean this is who we are. It’s not what we do it’s just who we are. You know what I think is unfortunate about the whole just talking about the fires in the Amazon is that when the fires happened a couple years ago or at least when the press around the fires happened a couple years ago. People said, ugh, you know, what’s happening with the fires we need to stop this. I’m like do you realize the fires happen every year, every year, every year. It’s just when there is a lull in the news or when the fires are bigger or when there's a scandal around it because there's a certain president who blatantly doesn't really care. The thing about telling a story about the fires in the Amazon is that, I’m gonna say the powers that be, I’m not gonna get political but political and corporate powers that be don't want that to stop. Because when the land is cleared, you can then so crop or put cattle. And so, if a land is cleared legally or illegally the trees are done. And the next thing that’s gonna happen is cattle grazing and agriculture. So, it's nothing new this is where the storytelling exhaustion kicks in. Because I feel like not just my family but so many people have been repeating stories over and over and over again. And at the same time going back to the previous question, it can't create eco-anxiety. The young generation really feels it. My son’s younger, he’s nine. He acutely knows what's going on because he sees me working every day. And when somebody says what does your mom do? He says, my mom is she’s saving the jungle and the indigenous people. I’m not doing that by myself. I think first of all we all need to take responsibility because the story is ours. And going back to the beginning of this conversation, you asked me about Beto Marubo. When somebody in the audience asked Beto of the Marubo tribe what can they do to help. They saw the film, what can we do? Beto says now that you’ve seen my story, keep telling the story because it becomes yours. And I think that that’s something that we can ask our audiences to do. Own the story like it's yours because then you will do something about it. So, whether it’s Amazon fires plastics in the ocean the polar bear, own the story like it's yours and then do something about it. Find your passion and follow-through.

Greg Dalton: Another question from our audience member watching the livestream. Sarah says, “Do you feel there's a way that environmental filmmaking can go beyond the visual showing conditions, people, beauty and solutions?” Davis Guggenheim, one of the critiques of Inconvenient Truth was it was short on solutions. Do you think now we can have a compelling story that is positive and shows solutions?

Davis Guggenheim: Of course, and I think there are so many incredible stories that have been told by the people, you know, by Cristina and Céline. And if you look at climate change it’s bigger than a world war which I think it is. It’s an inaccurate comparison, but let’s say World War II. There have been hundreds of stories about World War II. Some are very technical. Some are very historic. Some of them about a few soldiers some of them about people who were victims. Some are cultural some are romantic. Some are vilifying enemies. Some are lifting up heroes. And it takes that back to climate change I think there are thousands and thousands of stories that we will have to continue to tell.

Greg Dalton: The difference of course, Davis, is that we know how World War II ended. And I’ve heard Ira Glass for example, say, climate stores are depressing because we know how they’re gonna end we’re all screwed. And it’s like the ending is not a surprise and it also hasn't happened yet. So, doesn’t that create a challenge for storytelling of something as its unfolding?

Davis Guggenheim: It’s a huge challenge. It’s not like World War II where there’s, you know, Nazis to hate. I mean there’s places like Exxon Mobil which are truly evil corporations and they’ve acted very badly. But the climate change itself is not something you can look at and touch, right? And it affects you the positive things you do don't have immediate response it’s really hard and it feels impossible. It feels like what I’m doing doesn’t help and it feels like even if I do what I'm doing helps it feels too big. So, it’s probably the most challenging thing it’s for sure, the most challenging thing that humankind has ever made we've made it and it’s also one of the even more challenging for us to figure how to describe and to figure out how to fix. I'm overwhelmed by it I’m humbled by it.

Cristina Mittermeier: And yet, we have to.

Davis Guggenheim: Yeah, we have no choice. We have no choice.

Greg Dalton: Céline, you mentioned how your film subjects have asked only that you take their stories and make them yours. How are stories, you know, important in our culture and how can we do a better job passing them along?

Céline Cousteau: Well, I mean I think first of all let’s not forget that we’re all storytellers. I mean the three of us are here, you know, talking about our work and our careers as storytellers but we are sitting around a fire with a beer. You’re a storyteller coming home from holiday when we’re allowed to go on a holiday again. You’re a storyteller because you come back with those moments and those memories. I think first of all is to own your own story, but share it with others listen to other people listen. We, I have had to relearn the art of listening because listening with indigenous people is more time-consuming it’s more proactive. You’re there as an active listener, you can't be thinking about how you’re gonna respond you really need to be absorbing. So, I think those are all skills to relearn and to remember. And I think going back to what Davis was saying as well is that we are inherently all interconnected with this we need to be present with it. There might not be tangible solutions, but it is about consciousness. It is about that shift and unless we start reconnecting with nature reconnecting with ourselves and reconnecting with others, climate change is always gonna seem like this far away subject. So, I would say just start and sit quietly, contemplate. Let's get off of these all the time I'm just as guilty and just spend a moment reflecting about our place on this planet and with each other. And I think then we’re gonna start realizing what's truly important in our lives and that’s gonna start I believe a tied shift in our relationship with our own future.

Greg Dalton: We’ve been talking about visual storytelling with Céline Cousteau, Cristina Mittermeier and Davis Guggenheim. There’s another piece of documentaries and song and music is important part of the storytelling. Melissa Etheridge wrote the theme song titled “I Need to Wake Up” a roaring anthem about speaking up. It is the theme for An Inconvenient Truth. When I returned from the Arctic for the first time in 2007, I assembled the slideshow arrange that song and I cried at my kitchen table for weeks, putting it together. I still get mushy when I hear that song and I think it's underappreciated. There's no enduring theme song for climate in the way we shall overcome as for the rights or others. I think that song is as good as any. Davis Guggenheim, as a person who put that together I’m curious about how that song holds up. Clearly more people know the music than the song but I'm just curious in your thoughts about, plug for that song I think its powerful and it still holds up.

Davis Guggenheim: It’s a beautiful song. It really is incredible and it captured a moment and a feeling that, the theme of this show is visual storytelling, well, this is how songwriting can help. And it just shows you that it takes, it’s gonna take a lot of voices and a lot of different expressions. Scientists, filmmakers, photographers, songwriters, it takes all of us.

Cristina Mittermeier: Can I add something to that, Greg, if I may? Do you think, Davis, I mean there was a moment when we started talking about climate change when the conversation was truly cerebral. And I feel like in the beginning at least it left a lot of people out. People don’t like to feel stupid and just when you start looking at those graphs, you’re like oh I don’t get what they're telling me, you know, not think about it. But through song and through story and through photography we lower the price of entry into the most important conversation of our lives. And like you said, Céline, we’re all storytellers. And I feel that the stories that we’re telling somehow are empowering people to feel included and we’re giving them permission to become environmentalists to care about this issue. We need many more.

Davis Guggenheim: I agree a hundred percent. I also think we need to be conscious of how the urgency is changing. Like 10 years ago or 15 years ago we needed to convince people that it was real. And then we need to convince people that humans are causing it. And then you wanna convince people that this is the most urgent story of our time. It keeps going, right? The story and the barriers to understanding and taking full action keep shifting. And understanding where people are in the story and meeting them there. Like you both are in your work and you know all this is there’s a thing I’m always trying to crack that’s why I’m going back to my son and that sort of weird disconnect between him making a life choice about having children and then not talking about it. Like okay there’s something there. I’m always thinking of where are people in this moment.

Cristina Mittermeier: And then there’s something else because in the conversation about climate change, we often don't talk about the biodiversity loss that's going with it, right. These two parallel things. And they’re hand in hand, and the solution for a lot of climate change is going to be to protect biodiversity or to restore habitats. And so, we can't leave that part of the conversation out and allow the Elon Musks of the world to, you know, come up with a machine that solves the issue when we already have all the machinery on this planet that can solve the issue if we only we choose to protect it.

Davis Guggenheim: Yeah, I agree.

Céline Cousteau: I think this brings us back to an earlier part of the conversation with My Octopus Teacher where there's an emotional side the conversation and an intellectual side. And if we only focus on the intellectual side then it does seem daunting and overwhelming to your point, Cristina. I think if we focus on the emotional side then we’re leaving information out but to the point of Davis and your son and his friends, they're reacting on an emotional level not just on a logical level. I think all of that comes into play and it goes back to the psychology. So, I think you're right on Davis in this direction the psychology of climate change, this ecology of understanding ourselves in this current time and space. What is at stake do we understand it, what are we willing to do about it without going to panic button. Panic button only leads to chaos, right? We know chaos doesn’t solve anything. So, can we move forward in a thoughtful, meditative calm way where we actually provide people with tangible solutions where they exist and not try to get them to solve the world. Because I had a friend who told me once, oh I feel so good knowing you're out there protecting the planet. And I was like timeout, hold on a second. It's Tuesday I’m good. It's inclusive which I think is beautiful, right. It's inclusive it’s like, no, come with me I have beautiful things to show you and you can do something about it. I think that's what we’re all trying to do.

Greg: Filmmaker and explorer Céline Cousteau on telling climate stories in images and sound. We also heard from photographer and conservationist Cristina Mittermeier. And Davis Guggenheim, who directed the Academy Award-winning documentary An Inconvenient Truth

Greg: To hear more Climate One conversations, subscribe to our podcast on Apple, Spotify or wherever you get your pods. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. It really does help advance the climate conversation.

Greg: Sara-Katherine Coxon is our Senior Producer. Kelli Pennington directs our audience engagement. Tyler Reed is our producer. Steve Fox is director of advancement. Devon Strolovitch edited the program. Our audio team is Mark Kirchner, Arnav Gupta, and Andrew Stelzer. Dr. Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, where our program originates. [pause] I’m Greg Dalton.