Ai Weiwei: Human Flow

Summary

In his new movie Human Flow, artist and human rights activist Ai Weiwei documents the plight of refugees struggling in a hot and crowded world. Greg also talks to an artist who uses music to convey emotional urgency around climate disruption.

Bill Collins, Scientific Advisor, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

Stephan Crawford, Founder, The Climate Music Project

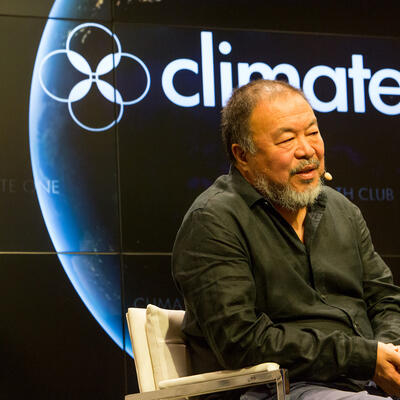

Ai Weiwei, Artist and Activist

This program was recorded at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco, CA.

Full Transcript

Announcer: This is Climate One, changing the conversation about America’s energy, economy and the environment.

Throughout the world, hurricanes, drought and sea level rise are hitting people where they live. In Africa and the Middle East, people are being driven from their homes by political and economic upheaval, amplified by the changing climate.

Ai Weiwei: Before the Syrian war there’s seven years of drought…many people think that also contribute to the upheavals in the nation.

That’s artist and human rights activist Ai Weiwei. In his new film “Human Flow,” Ai documents the plight of refugees struggling in a hot and crowded world.

Later, we’ll hear about using music to convey emotional urgency around climate disruption.

Stephan Crawford: As an artist, I wanted to try to find ways to use art to make it less abstract.

Announcer: Art, freedom and people on the move. Up next on Climate One.

Announcer: How can art help us understand the human costs of climate change?

Welcome to Climate One – changing the conversation about America’s energy, economy and environment. Climate One conversations – with oil companies and environmentalists, Republicans and Democrats – are recorded before a live audience and hosted by Greg Dalton.

Ai Weiwei spent much of his childhood living in political exile with his family in Xinjiang. When the Cultural Revolution ended, the family returned to Beijing. During his twenties Ai lived in the United States, where he was exposed to the works of artists such as Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol, befriended poet Allen Ginsburg, and earned a reputation as a top tier professional blackjack player. He gained artistic success and international recognition for using his art and social media to comment on politics. This led to his arrest and detention for by the Chinese authorities. Ai now lives in Berlin and travels the world pursuing his art and his activism.

Ai recently spoke with Greg Dalton about his latest project, “Human Flow,” a film documenting human migration and the refugee crisis.

Greg Dalton: Let’s begin with your dad and the story of your dad and how that it kind of comes to the film. Your dad was the renowned Chinese poet Ai Qing who joined the Chinese Communist Party and was sent down to the countryside for a long time where he had to, you know, clean toilets. So tell us how that shaped your empathy for what the film’s about. How did that influenced you?

Ai Weiwei: Well, the year I was born which is in 1957 my father was exiled. So our whole family had been sent to the most remote area very far from Beijing, Xinjiang.

Greg Dalton: The far west.

Ai Weiwei: Yes, far as you can get. Yeah, a little bit farther would be Russia or Pakistan, you know. So talk about another story. So I grew up in this very extremely harsh condition, you know, my father becomes anti-revolutionary. And in that society that’s the worst of crime you can commit is an anti-revolutionary. So since I was very young, I experienced all those very harsh political conditions like the discriminations, all those. And basically we have to live in a hole underground so to tell you the condition, yeah, fortunately the Gobi desert is not so much raining in the summer.

So that make me much easier to approach this film, Human Flow, and to see this human tragedy as part of my condition, you know. I feel there’s some connections in there, you know, the people, there are 65 million people being forced out of their homes. There’s no single one which is willing to leave their home, to give up their land.

But there’s 100,000 people killed in this kind of dramatic war, famine, environmental problems, they have to leave. So I think it's global situation. It can happen to most like anywhere and they’re really testing our humanity and especially to the people who are privileged and to challenge our understanding about human condition.

Greg Dalton: So do you feel a responsibility to bring this story to people who are comfortable and privileged?

Ai Weiwei: First, it's my personal journey. I want to understand the situation. I think to really draw any kind of conclusion first, that you need to be conscious and to know what is really going on. The scenes looks very complicated, many, many issues are very different, you know, some are more historical, some are religious problems, some are just current original conflicts. But what come to the conclusion after like going through this one year of filming, we went through about 23 nations, 40 camps. I interviewed about 600 people come out around 900 hours of footage. So then gradually you see even the condition are very different but they basically are the same. They are being forced out from their original home and have nowhere to go.

And some, a very small proportion about less than about a few percent of the people come to Europe which already made a big problem in Europe. And I’m settling in Germany now in Berlin so the German already take over one million for refugees. But most of them are still in camps after two years or one, two years of being in Germany. So it’s very difficult for any of them to really to be integrated into this society, you know, only very small portion maybe three percent of people has been really settled in some way. The rest they stay in the camp and which is very harsh condition to think about. Europe is a society which has plenty of resource to helping those people but the opinions are very divided and the policy also changing. You know, many refugees have been sent back to very difficult areas such as Afghanistan or some other places.

Greg Dalton: You make a point in the film that the refugee convention was born in Europe. And you seem to really pressure Europe to sort of rise up to that legacy of obviously coming out of World War II. What do you think Europe should do?

Ai Weiwei: I think it’s not a matter of just Europe. I think we have to see it as a global problem. And of course Europe was, you know, is close to Syria and also the Africa refugees come to Italy. So naturally, those people can reach the border there. But in this situation it’s really a global situation because you could see what caused those refugees. Many refugees come from Iraq, you know, even the extreme groups created by Iraq war in which U.S. is deeply involved. And Afghanistan, war, you know, also many, many other locations. And in Myanmar, you know, what happened in Bangladesh, Myanmar now.

Greg Dalton: And that’s changed the politics in Europe. Some of the Brexit, you know, recently the elections in Germany, your adopted country, where the right came up. Can you understand those people who feel threatened by so many refugees?

Ai Weiwei: I think there are several layers of the problem. First, those nations do have this kind of rightist or even some are really, they have this root, you know, this dust is always there it’s just been stirred and it came to the surface, you know. It’s deeply have those kind of tendencies and roots in Germany, especially and in many, many nations, you know, we cannot forget what happened a few decades ago.

You know, as human being nothing can just disappear as, you know, so once things getting difficult, politicians always use this to gain the popular vote. This is obviously same as U.S., you know, if you see the policies happening in U.S. which is also quite shocking if you think the policy to reduce the acceptance of refugees to such a small number. Even in the previous administration it’s not high, you know, to compared to other nations sharing of refugees but now it’s getting extremely low. And also in many cases to set up this kind of traveling ban or to even have this intention to move away the people already, some are born in here, some are, you know, have been here for decades to send them back or send them away. I think this is strong trend for violating those human rights and beliefs or the values which is most important values for to create this nation because we all, children of immigrants or refugees just some decades ago. So that’s really challenges this society to see the most powerful society, most privileged society and not bearing the responsibility and shying away from defending human condition and human rights.

That only means the society become less courage, no vision and the lacking of responsibility and the whole kind of this society leading our world to change, to make the positive change for this very crucial time.

Greg Dalton: Climate change makes a lot of the conditions that drive refugees from their homes worse. Drought, famine, the drought in Syria has been identified as a contributor to accelerating or amplifying that Civil War in Syria that sent refugees into Europe. What are the climate impacts that you see that underlie this mass movement of people?

Ai Weiwei: I think before the Syrian war there’s seven years of drought which also many people think that also contribute to the upheavals in the nation. And if you talk about Bangladesh and the flooding in that area and also kind of, you know, it’s about same time as Houston's flooding. But only difference is that we see our press always focus on Houston which I believe there’s no human casualties but Bangladesh resulted in people lost their life but then almost nobody talk about it.

So you can see this is very common if we see life or our property of life those are being treated very differently, in our media or in, you know, our public attention. Then you see the world is really divided. It’s divided because that’s against our notion about human are created equal. And if we accept that condition the world is, life has different values or divided, then in many sense much bad can happen, you know, that’s predictable.

Greg Dalton: But isn't that natural the way humans evolved to think about their clan or their tribe, that empathy dilutes with distance? The further something or someone is away from a person they have less empathy. Is that normal or do you think that that is --

Ai Weiwei: It is normal, it’s part of our humanity just to not to care about others. But also from the ancient time, this is also part of our concerns of early philosophy to see human as one, humanity as one, you know, human rights as one. If someone’s right is being violated, we all get hurt. If we don’t have this kind of understanding the problem, you know, someday we all can be get hurt because if we only have for this kind of visual condition to see us as one family or one which so closely associated, then we can have our empathies and we can come up some kind of solutions.

Announcer: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation with artist and filmmaker Ai Weiwei. We’ll be back with more, right after this.

Announcer: Today on Climate One, Greg Dalton is talking with artist, activist and filmmaker Ai Weiwei. His film “Human Flow” depicts the plight of refugees fleeing political and economic upheaval. Lurking behind the flood of refugees from Syria, Niger and other countries are droughts, desertification and other factors amplified by the changing climate. Let’s continue with their conversation about art, activism and freedom.

Greg Dalton: In 2011, the Chinese government detained Ai Weiwei for 81 days. Here's coverage from ABC's Nightline about his ordeal.

[Start Clip]

Female Speaker: The confrontation brewing between Weiwei and the government finally reached a dangerous tipping point in April, 2011 when he was taken into secret detention by Chinese authorities.

An international outcry erupted for his release. But the government accused him of pornography and tax evasion and held him for 81 days. When he was finally released, he was shaking.

Ai Weiwei: Sorry, I can’t.

Male Speaker: You can’t talk? You’re not allowed to talk?

Ai Weiwei: I’m on probation.

[End Clip]

Greg Dalton: That’s Ai Weiwei on Nightline saying he's on probation after being released. How does that make you take you back to that moment when you are in detention, you came out, your father gained notoriety after he had been detained. So how is that for you to come out of that detention experience?

Ai Weiwei: Well I used to be jealous about my father for only one thing is he has been put in jail for years. And I thought that will never happen to me, I don’t have this kind of privilege.

[Laughter]

I was, yeah, you know, enemy of the state it’s not easy to become.

[Laughter]

Such a powerful state but surprisingly it become a reality. I wouldn’t believe I was kidnapped, you know, from the airport being put on this black hole, taken to a location nobody knows where. It’s kind of like a military base secret and even soldiers serving in that location doesn't know where they are. You know, they are also being, joined the Army put them on a sealed van and taken to that location.

And of course in China you cannot talk to a lawyer or your family doesn’t know where you are. And, you know, like you’re dropped into a black hole and totally cut off from any reality. You don’t know if people really care about your disappearance or it’s just simply anything, doesn’t know anything about the site. And that kind of tactics are really working. I think any human being put in this kind of situation would have, gradually have very different understanding about your relations to the world. And, you know, I think the power very clearly trying to tell you is you’re very vulnerable, they are ruthless and, you know, they don’t have to follow the law, nothing can stop them if they want to do something.

Greg Dalton: You challenged power, the concentration of power in the Communist Party in China, and yet you were called at one point, the most powerful artist in the world. So how do you think about your own power?

Ai Weiwei: My power. It’s very funny, you know, the last moment before they gave back my passport that means I can freely travel. They sincerely sit down with me, you know, I talk with secret police. He said that, Ai Weiwei, you know, we know each other for so long.

[Laughter]

Yeah, it’s like an encore or, you know. And he is very human, very, you know, I start to like them because they really talk to you in very human language.

He said, “Tell me the truth. Many people said they become so well-known only because of us.” I said to them, I said, “Yes, it takes a very powerful nation to create a great artist.”

[Laughter]

And sincerely I said “That if not for your effort, I will never become Ai Weiwei today.”

Greg Dalton: We’re talking today with the artist and activist Ai Weiwei. We’re gonna go to our lightning round. Two parts. First part, I’m going to ask Ai Weiwei, just mention a name and ask him to say the first thing that comes into your mind, unfiltered which I think is --

[Laughter]

-- kind of the way you roll.

[Laughter]

First one is Mao Zedong.

Ai Weiwei: You don’t have a time like a clock or something?

[Laughter]

So does anybody know Mao Zedong here?

[Laughter]

He’s I should say the last emperor of China.

Greg Dalton: Okay. Andy Warhol.

Ai Weiwei: I wouldn't say he's my lover because he's someone I think represented the U.S. culture.

Greg Dalton: Blackjack.

Ai Weiwei: Is the game I used to play in Trump’s Taj Mahal.

[Laughter]

And yeah, lost a lot of money there.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: So you donated to Donald Trump, okay. True or false. Art can be intimidating?

Ai Weiwei: Yes, art is quite a very offensive, very fragile.

Greg Dalton: True or false. Cats can open doors?

Ai Weiwei: Yes, my cat.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: Last question. But they never close them?

[Laughter]

Ai Weiwei: That's also true.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: Alright. Let’s give him a round, Ai Weiwei, for getting through the lightning round.

[Applause]

Lots of cats in your life. Let's talk about China's progress because you’ve been very critical about human rights in China. I lived in China in the late 1980s as a student and a journalist and go back now. There's been tremendous economic material progress.

Your thoughts, Ai Weiwei, on China's progress. You came out just after the opening reforms after the Cultural Revolution.

Ai Weiwei: Yeah. I think China made tremendous progress and this progress is a huge contribution to the world civilization. I mean past 30 years, China come from a society almost like North Korea today or even worse and, yeah, become a state which is quite economically powerful. And almost no famine in China which the 1.3 billion people from very, very, you know, bad condition and China still plays an important role in world politics. So that's the progress side.

Greg Dalton: And there's been a great environmental cost of that progress. There is a term, environmental refugees, people who want to leave Beijing and other cities because it's so polluted. So address the environmental dark side of that progress.

Ai Weiwei: I think to have these risks of China, this many, many dark side, of course the environmental problem which China sacrificed just to make anything which nowhere I want to make in order for this profit to become, you know, to make this competition they would do it.

And so they polluted their air, river, you know, all those every possible conditions. And it will leave a big scar on China maybe permanently because there are so many issues relating to this environmental problem. And besides that this huge corruption and the tremendous problems relating to education and also the society even become very rich. Still the power never solve the problem of to be legitimate power because it's not elected power. And the internal struggle inside the party is always there and the people -- there’s no citizen because if you don't vote you have no voice, you don’t bear any responsibility. So there’s no trust in the society. So those problems can never be solved and also there’s no real creativity, you know, whatever they do is copying the west or, you know. And it's very hard to have any real creativity because there’s no encouragement to offer individualism, no freedom, no freedom of speech. So when those things are lacking, the society does not have creativity.

Greg Dalton: We’re talking with the artist and activist, Ai Weiwei, at Climate One. I'm Greg Dalton.

Let's talk about some of your installations. You’ve used life vests and wrapped them around columns in Berlin, thermal blankets to wrap around your art. In the Laundromat exhibition you took refugee castoffs and then pressed and cleaned them and gave them new dignity. So how can art convey the importance of something like refugee crisis?

Ai Weiwei: I believe the consciousness is very important, only by informed we can really take some kind of action, we can make our judgment. And so as an artist, I first need to convince myself that's why I got involved to make those films and to go to those locations and I have to be totally convinced what I'm doing. At the same time, I create some works in dealing with museums or public art. Certainly there is a large demand on that. So I put my works into my museum shows and in the past year at least I have about 10 or more museum shows and each of them I integrate to works relating to refugee conditions. I was only trying to show the people what I have been involved with, and to what degree they can affect others I don't have the idea.

Greg Dalton: We’re talking with the artist and activist, Ai Weiwei, at Climate One. I'm Greg Dalton. We’re gonna go to our audience questions and the first question is.

Male Participant: After 30 years of economic and material gains in China, but with the conditions of the Communist Party, no elections, no freedom of speech, how long do you think it can continue?

Ai Weiwei: For my prediction, I made a prediction six years ago, I said, well, we will end it in three years so that means we passed my prediction two years.

[Laughter]

You know, so essentially you cannot trust someone from the left.

[Laughter]

Female Participant: [Foreign language spoken]. So I really thank you for everything that you have done in your life. And one thing I think you should talk about is your soul because I have friends in China and they're telling me everyone is in this mad commercial rush to buy and sell and get things. I don't know how they resolve, if ever, the contradictions of that society. And I don't know if you still have family there. So how do you communicate with them and are you allowed with a passport to go back and forth. I don't think you are yet, are you?

Greg Dalton: Thank you.

Ai Weiwei: So first, I think you speak very good Japanese.

[Laughter]

Second, about soul I think I should leave that for the Dalai Lama because otherwise he would have nothing to do.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: The materialism of China, they’ve become so rich, so fast, have they lost something?

Ai Weiwei: I don't think that's a problem. I think the problem is the Communist Revolution. That's the true problem when they killed all those landlords and made the whole society -- what carries the culture used to be those landlords, you know, the farmers don't really know the culture and basically it’s a federalist society. All those landlords are rich people who carry the culture. So when they completely have this kind of very brutal revolution, just kill all of them, that had stopped the culture for a while. And then later, of course, this communist society heads up to take in all the private properties which also can cause tremendous problem for the society because once you don’t have any property, you will not really care or build anything because you don't have anything to give to your children. And those have much bigger impact on China and China still cannot solve those problems. And even today people are getting rich, it’s only very restricted condition because you’ll never know and because the party encourages you to be rich, you know.

So most people got rich either they benefit from the policy and of course they also can be arrested for corruption because anybody related to the party would first get to benefit from this and become rich, you know. And also if you're outside of the system meaning, you know, so-called independent entrepreneur then that's even more dangerous because the party can get on you any time. So this is a society if you don't have an independent legal system which will put everybody in danger and that's why, you know, so many rich Chinese moved out to California.

[Laughter]

And certainly in the past few years we have a much better Chinese restaurant than ever.

[Laughter]

You know, yeah, people buying real estate and, you know, which benefits here.

Greg Dalton: Let's go to our next question for Ai Weiwei.

Male Participant: I’m curious what attracted you to settle in Berlin and under what conditions would you return to China.

Ai Weiwei: For years I don't have a chance to travel and suddenly they gave back my passport and still I don't know. I feel very lucky I do have the chance so they’re being soft on me.

And the question why I have to go to Germany, I will tell a story. Right after I got my passport, the American Embassy called me. They said please come over, I said okay. The next day I will to leave. So I walked into the Embassy, the ambassador, he is a very respected man, and he asked me why go to Germany.

[Laughter]

So I said Germany had made a tremendous effort. You know, Merkel, you know those politicians from Germany, they are very stubborn. They keep asking Chinese authorities why you don’t let this guy go, you know, I was already given a professorship in Berlin, why he cannot come to teach. So that made the Chinese government quite embarrassed but of course they are also more stubborn than Germans.

[Laughter]

So even before the Germans asked them, they said uh-huh we know you’re gonna ask about Ai Weiwei. But they have a lot of deals, business deals, you know, so it’s to both benefit; it’s better to release me because, you know, that's what, how I understand.

Announcer: You’ve been listening to a conversation with the Chinese artist and human rights activist Ai Weiwei. His new film is called “Human Flow.” When we come back we’ll turn to another art form being used to connect human emotions and climate disruption.

Announcer: Musicians and scientists in California are collaborating on a time machine that helps people hear - and feel - what the climate system sounded like when the industrial revolution began. It was a lot calmer and quieter, with all that coal and oil energy still sleeping in the ground. They also take people into the future, when the release of carbon pollution into the air creates unsettling and chaotic sounds, evoking images of hurricanes, floods, fires and other climate-driven extreme events.

The Climate Music Project performs before live audiences with scientific charts of temperature and carbon concentration pulsating on huge screens above the musicians. Bill Collins is a scientific advisor and head of the climate division at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Artist Stephan Crawford founded and leads the group. Here’s Stephan Crawford.

Stephan Crawford: I think for too many people climate change, the issue of climate change is still an abstract concept. And the idea was as an artist, I wanted to try to find ways to use art to make it less abstract.

We’re trying to make people be aware of the urgency of action on climate change. And I think there is a hopeful message there and the hopeful message and Bill I’m sure will address this is that there's still a window of opportunity to act to have a better outcome than if we do nothing today.

Greg Dalton: And Bill, you spent a lot of time with computer models looking at the future very sophisticated and quantitative. What made you want to get involved and connect music to climate science and data?

Bill Collins: It had become clear to me that scientists needed other channels of communication around climate science. We needed to not only convey the signs accurately, but also convey really what it meant and what it means on a more than just an intellectual level. And that's what led me to seek other forms of expression besides the usual ones that I employ in my daily work.

Greg Dalton: So there's hope here we can make a better planet or build a better economy. It’s not all just downside and risk.

Bill Collins: People who look at this problem very seriously have shown that that's in fact possible that we can mitigate climate change, maintain a highly developed in fact even more developed way of life but restore some balance in the way that we interact with our natural surroundings. And also really get at some of the roots of increasing poverty that’s associated with resource contention and some of which is coming about directly because of climate change. So this really could be a win-win situation if we start to address it soon.

Greg Dalton: Stephan Crawford you got together some composers, you have Bill as your science advisor and you composed some music. So tell us how the music conveys these scientific principles.

Stephan Crawford: Well, music is a universal language and in this particular case we have our first, we’ve been performing our first piece for the last two years now. And the first piece is called Climate; the composer is Erik Ian Walker who composed the piece. That piece basically spans about 300 years so it looks back into the climate’s past, the present. And then it looks at two scenarios moving into the future.

And over that arc which is about a 30-minute arc. So every minute is about 25 years in the climate system. So what's beautiful is that when using music as an analogy it’s almost like a Time Machine. How else can you take an audience today show them what the past was like, take them to the present and into the future to show them different possibilities of what the future could look like and then bring them back to the future in time still to act. And that’s what the piece does.

The piece uses a technique called parameter mapping which is where you identify variables in the climate system that you want to model and then you assign musical analogs to those variables and that’s how the music plays out essentially.

Greg Dalton: So you're taking us into the future through music and you are giving us one scenario which is business as usual.

Stephan Crawford: That's right.

Greg Dalton: And another scenario is which we heed the warnings of flashing red lights that scientists are telling us. And that's another sound or another future, okay. Let’s hear one of those futures from the Climate Music Project.

[MUSIC]

Stephan Crawford: This is the early 20th century actually.

Greg Dalton: So this is when the automobiles being invented and electricity and it just starting. So the industrial economy as we know it is just beginning.

[MUSIC]

Greg Dalton: Pretty calm music I’d say.

Stephan Crawford: Pretty calm music. But the composer through the course of the 20th century in this particular piece carbon dioxide actually controls the tempo of the piece. So as more carbon dioxide is emitted, the tempo increases. And then the four variables and Bill you might want to add some detail here. The four variables were carbon dioxide, near earth surface temperature, earth energy balance and then ocean pH were the four variables. And so the tempo was controlled by carbon dioxide. Pitch is controlled by the temperature. And then earth energy balance controls distortion in the music. And then the overall form of the piece is controlled by the ocean pH.

And so as the 20th century progresses and CO2 rises in the atmosphere, the tempo of the music picks up and that in turn that affects both the pitch and level of distortion. So as long as the variables are relatively flat and not static then the music sounds like music as they change and become more dynamic the music also becomes more dynamic.

Greg Dalton: And Bill Collins, tell me if I’m an average citizen why I should care about earth energy balance or pH balance. How do those things affect average people?

Bill Collins: Sure. So we chose this four because they're all interconnected. And as you increase carbon dioxide, you make the earth's atmosphere act more like a heat blanket and that shows up in the energy balance. It drives the earth system out of balance. And in fact there’s a net input of energy into the system which causes it to warm. So sort of connect from carbon dioxide to a positive energy balance to increasing temperature that's a chain of causality that connects all those three.

Greg Dalton: And energy balance is that the energy coming from the sun that it stays?

Bill Collins: The sun’s insulation or the amount of energy we’re getting from the sun is more or less staying the same. What’s happening is that we’re reducing the amount of heat that we’re radiating to space. And sort of this issue you put on a thicker and thicker coat and so reducing less heat in your environment. At some point you put on too many coats, right.

And the pH of the ocean is really very critical because of its impact on the web of life in the ocean. The most simple organisms in the ocean that form the bottom of the food chain for all of oceanic life. Many of them have -- they’re like ants they have exoskeletons or heart outside that is made of substances that dissolve when the ocean becomes more acidic. As you drive on making the ocean pH change means in English making the ocean more acidic. As you make the ocean more acidic, it becomes harder for this very simple organism, that form the bottom of the food chain to survive, which makes it harder for them to survive. You have ripple effects that traverse the food chain including, you know, all the way up to the sushi that you're eating in a market. So those impacts have very -- the ocean pH has very big impacts on food chains that we care deeply about.

Greg Dalton: So we have those four factors and you’re conveying them musically and we heard the early of 20th century. Can you play us 2017?

Stephan Crawford: So let me play this next clip which will be, it starts 1960 but I can fast-forward it, it goes to about 2025. I’m not gonna play the whole thing but you can already hear it sounds much different.

[MUSIC]

Okay, I’m gonna fast-forward it just a little bit here.

So you can hear that distortion starting and you can also hear the tempo increasing.

Greg Dalton: It’s faster.

Stephan Crawford: It’s faster. And this is still not even up to our current day yet. So let me fast-forward to about where we are today.

[MUSIC]

Greg Dalton: So Stephan, take us into the future where what do we looking at

Stephan Crawford: This is just before the year 2150 and this is the worst, okay, this is I guess the business as usual scenario. Most of the piece follows and this is right before it shifts off to an example of the other scenario. But let me just play this before 2150.

[MUSIC]

Greg Dalton: So that’s 2150. Was that the business as usual scenario?

Stephan Crawford: That was the business as usual scenario.

Greg Dalton: Okay. And then is there an alternative scenario where the earth de-carbonizes the economy and we avoid the worst consequences.

Stephan Crawford: There is and in fact right after, there’s a part in the music right after 2150 where we drop down to that scenario just for about a minute or so which is the 2 degree world essentially the Paris agreement world.

We’re looking to add a visceral element to climate literacy. To tell people not, you know, and in fact one of our audience members told us that through the music she was able to feel the issue in a visceral way that she could never understand and what had been abstract for her before. And so that's where we’re looking for is to sort of spark that insight that this is actually something that is personal to me that I can feel.

And then a big part of our projects is not just to put on concerts. It's also we’ve been actually very actively building an action network with existing NGOs, both on the climate literacy side but also on the climate action side to essentially be able to channel our audience as a mode of energy directly into these partner organizations. So the people once they go to the experience they don’t have to go home alone and just sit there but actually they can find ways to connect with other people, to learn more about the issue, to ask more questions, to build community around the issue. That's really why we exist not just to put on concerts.

Greg Dalton: Okay. Bill Collins, you know, is there hope? Is there, you know, some people think that we really not gonna turn this around that the 2 degree scenario that’s conveyed in this music is not really possible.

Bill Collins: I frankly find that to be a rationalization for doing nothing.

Any action is worthwhile. No action is insane.

Greg Dalton: And so if we care we are all morally bound to do as much as we can?

Bill Collins: This is, the rationalization that, you know, it may be difficult to hit 2 degree since we shouldn’t stop is exactly the same rationalization that you’ll hear an alcoholic give for not kicking the habit. It is exactly the same rationalization and it’s equally indefensible.

Now this is, we have an addiction it’s like any other addiction. It’s led to a great party. We’re facing it; to pursue this analogy a little bit further we’re facing the world’s worst hangover. Be really smart to quit and to stop rationalizing.

Greg Dalton: And as we close your thoughts on, Stephan, art as part of social change.

Stephan Crawford: I think art has to be part of social change more than ever now. I think that’s art has a huge role to play because art can make people see things that otherwise might be hard to see. And I think now more than ever we need the creativity and there is so much brilliant creativity out there that I think and in this project we also wanna, our goal is to really leverage a lot of other brilliant set of beyond the brilliant minds we’ve already leveraged in terms of our technology people and our composers and musicians. We want to reach out and try to sort of open source that process so that we really can take advantage of all the brilliant minds out there who are very creative they can find new ways to express this and new ways to touch people. Because I think what really is important is that people feel this and they were touched by it. If they’re touched by it, then it’ll be real for them and they’ll be able to actually integrate it into their lives.

Greg Dalton: And Bill your closing thoughts on bridging art and science and social change.

Bill Collins: I think scientists realize that we need to partner up to solve this problem. And some really incredible partners have and will come from the artistic community. And the Climate Music Project is one of several attempts to bridge that gap. I am really heartened by the success that we've had so far and look forward to many future successes.

Announcer: You’ve been listening to Climate One, hosted by Greg Dalton. Greg’s guests today were artist and activist Ai Weiwei, Bill Collins of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and Stephan Crawford of the Climate Music Project.

Podcasts of this and other Climate One shows are available wherever you podcast, and on our website: climate-one-dot-org.

Please leave us a comment; we’d love to know what you think about our conversations on energy, food, water and more.

Greg Dalton: Climate One is a special project of the Commonwealth Club of California. Kelli Pennington directs our audience engagement. Carlos Manuel is our producer. The audio engineer is William Blum. Anny Celsi and Devon Strolovich are the editors. The Commonwealth Club CEO is Dr. Gloria Duffy.

You can discover additional podcasts, videos, speaker information and more at climate-one-dot-org. Join us next time for a conversation about America’s energy, economy and environment.

Climate One is presented in association with KQED Public Radio.