Weird Winters

Guests

Elizabeth Burakowski

Kit Deslauriers

Geraldine Link

Mario Molina

Summary

Warmer, shorter winters may sound like a relief, especially on the heels of this year’s deep-freeze in Texas and record blizzards in Wyoming and Colorado. But rising temperatures and smaller snowpacks could disrupt more than just ski vacations.

“The snow sports industry contributes about $20 billion to the U.S. economy every year,” says Mario Molina, CEO of Protect Our Winters, “and in low snow years or shortened winters, that contribution goes down by about $1 billion.”

Molina estimates that between 36 million to 40 million Americans identify as skiers, climbers, trail runners or mountain bikers and consider it a key component of their physical and mental health. As such, not only is the outdoor recreation community a far larger constituency than we may think, but so are the people whose livelihood and local economies depend on it.

“If we're not able to ski or snowboard anymore, the least of our concerns will be the activities that we participate in,” Molina says, adding that “if it’s at that point, it means that we've crossed a certain threshold where not only there's huge risks to the entire economy but some of the very systems that we depend on.”

Elizabeth Burakowski, a climate scientist at the University of New Hampshire, studies the impact of changing snowfall patterns on those systems.

“When you have a low-snow winter ... you end up with dry soils, dry ecosystems that are much more ignitable,” says Burakowski, ”and that can spell danger not just for ski areas, but for a lot of people that just live in the region.”

Record-setting blizzards are a further indication of the increased volatility of winter weather.

“If you have that warmer atmosphere and it's still just below freezing you can hit this atmospheric sweet spot where you can end up with a really big storm,” she explains, “the problem comes a little bit further down the line, that is keeping that snow on the ground.”

Ski mountaineer Kit DesLauriers, the first person to ski down the tallest mountains on each continent, is also acutely aware of the changing winter climate, especially its effects on her beloved spring skiing.

“It’s just my favorite thing, that time of the year when the valleys are green below and the snow is still up high and the climbing is a bit more technical,” she says, “[but] that season has pretty much disappeared in the last several years.”

Related Links:

Protect Our Winters

Higher Love: Climbing and Skiing the Seven Summits

National Ski Areas Association

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. [pause] Warmer winters may sound like a relief, especially on the heels of deep freezes and record snowfalls.

Geraldine Link: You can’t just look at how much snow we have. The timing of that snow is really important when we're looking at climate change.

Greg Dalton: Rising temperatures and smaller snowpacks could disrupt more than just ski trips.

Mario Molina: The snow sports industry contributes about $20 billion to the U.S. economy every year. And in low snow years or shortened winters, that contribution goes down by about $1 billion.

Greg Dalton: So how are winter sports enthusiasts and others preparing to weather the storm?

Elizabeth Burakowski: If they’re skiers or snowboarders, like snowmobiling, ice fishing, or even just snowshoeing. Wouldn’t they be maybe the person who would notice a change in their environment?

Greg Dalton: Weird Winters. Up next on Climate One.

---

Greg Dalton: What will change in a world of warmer, shorter, and wetter winters? Climate One conversations feature all aspects of the climate emergency: the individual and the systemic, the exciting and the scary, people who are in power and people who are disempowered. I’m Greg Dalton.

Greg Dalton: From backyard trails to the top of Mount Everest, skiing may be the consummate winter sport.

Kit DesLauriers: I just love it it’s just my favorite thing that time of the year when the valleys are green below and the snow still up high.

Greg Dalton: That’s ski-mountaineer and National Geographic Explorer Kit DesLauriers. In 2006 she became the first person to ski down the tallest mountains on each continent. She climbed up Mount Everest and then skied down.

Kit DesLauriers: I was kind of like, “You guys, get out of the way!” Because there wasn’t a lot of room up there.

Most people will never try something so extreme, but volatile winter weather is having impacts far beyond skiers.

Mario Molina: If we're not able to ski or snowboard anymore, the least of our concerns will be the activities that we participate in.

Greg Dalton: Mario Molina is the CEO of Protect Our Winters, a community of athletes, scientists, and business leaders dedicated to preserving the great winter outdoors from climate change. We’ll talk to Mario and Kit later on today’s show. First, the science – and experience – of shorter, weirder winters.

Elizabeth Burakowski: I was trying to describe this eerie feeling that I would get when we have these 70° days in the middle of winter. It just doesn't feel right. Something felt off, it almost felt like you’re in a strange land.

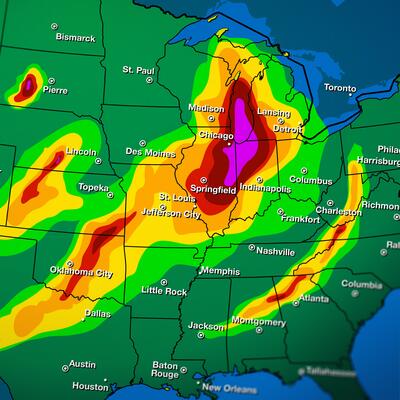

Greg Dalton: Elizabeth Burakowski is Assistant Professor of Earth Sciences at the University of New Hampshire, where her research focuses on how landscapes interact with surface climate. Given this year’s deep-freeze in Texas and record blizzards in Wyoming and Colorado, you could be forgiven for thinking the future of outdoor winter recreation is as bright as freshly-fallen powder.

Elizabeth Burakowski: For this particular winter season in Colorado I mean as of today, which is mid-March 2021 we’re actually looking at the state, you know, they got a huge blizzard but they're still well below average for their snowpack. And that’s really critical not just for their ski industry but for water resource management. A lot of their drinking water supply and agricultural water supply comes from water storage in the mountain. It's also a really good buffer against forest fires that are happening later in the summer. And when you have a low snow winter it means this can be a complicated relationship where you end up with dry soils dry ecosystems that are much more ignitable and that can spell danger not just for ski areas, but for a lot of people that just live in the region.

Greg Dalton: How are big snowstorms an indication of warming? So, if I understood you correctly, there can be big storms, but the total for the year is less. So, it seems like snow is coming in different packages or different bursts.

Elizabeth Burakowski: Yeah. I mean there’s a nice way of putting it basically the wet get wetter the dry get drier. It’s kind of a common mantra among climate scientists to describe the overarching changes that we can expect in the climate system. And that's certainly true when we’re looking at winter, we can expect to see more winter precipitation, at least in the Northeastern United States that's what we're seeing in our climate model simulations. And that doesn't necessarily mean that we’re going to get a lot more snow. In order to get snow, we need that precipitation to come in the form of snow not rain. And unfortunately, southern parts of our region in the Northeastern United States are looking at major shifts and specifically the shift from being below freezing average winter temperature to above freezing winter temperature. And that means that we’re gonna see more winter rain we’re gonna see more midwinter rain on snow events that melt away the snowpack and make it harder to maintain especially for skiing operations. And it could also mean that like you have said, more of our snow is gonna be coming in these big packages, whereas those small spurts of a couple inches at a time that really helped to refresh the snowpack and keep it nice and skiable, those are becoming much rarer. There's been a lot of studies that have come out from various groups that have looked at this and it all boils down to the fact that a warmer atmosphere simply holds more moisture. So, if you have that warmer atmosphere and it's still just below freezing you can hit this atmospheric sweet spot where you can end up with a really big storm. The problem comes a little bit further down the line that was keeping that snow on the ground. And warmer winter temperatures overall have led to trends in snow disappearing earlier in the spring, which shortens your ski season on that end. And it also means that snow is generally also coming kind of a little bit later. Most of the signals we’re seeing, at least in the Northeastern United States, though, is pointing toward an attrition of the snow season at the end of the year so the spring part of the year.

Greg Dalton: Sounds like a lot more slush.

Elizabeth Burakowski: Yeah, and I got to tell you slush is not my favorite for skiing. I am a big fan of spring skiing. I certainly have my sundaes and the mashed potatoes and you get your spring corn as they call it. But overall, this slush, skiing on a rainy slushy day is generally not people's preference. And instead of going up to the mountains and taking a ski day or booking a vacation. They might cancel it and decide to stay home because really no one likes skiing in the rain especially not children I’ve learned lesson this year.

Greg Dalton: Right. And I'm thinking not even just the ski slopes or just around town you know slushy mushy dirty versus the, you know, white snow. And there’s something you talk about backyard syndrome that contributes to people's attitude toward skiing. So, tell us about what backyard syndrome is.

Elizabeth Burakowski: Yeah. So, I work with a sociologist here at University of New Hampshire. And Dr. Larry Hamilton is very interested in how people perceive things and what their feelings are when they decide to act on a behavior or an action. And one of the studies he did here at UNH was to look at this backyard syndrome. So, what he found was essentially that people that are in the Boston area are much more likely to go skiing in the North Country of New Hampshire what we call the North Country, if there are snow in their own backyard. So, it doesn’t matter how much is back at the mountains, the mountains here in the Northeast, 98% of the terrain is usually able to be covered by machine made snow. So, they can invest a ton of technology and money in that equipment and put the snow on the ground when mother nature is not providing. But you got to get the people from Boston to come up there because they’re a big chunk of the number of people that come to ski in New Hampshire. And if you don't have them, I mean the locals can only pull so much of the economically in terms of buying tickets and buying season passes. We really rely a lot on people from Massachusetts and New York coming up to do their skiing.

Greg Dalton: One report says that northern states are warming faster than southern states. That was surprising to me. How are different parts of the United States being affected?

Elizabeth Burakowski: The Northeastern United States is a hotspot for winter warming, as well as the Midwestern U.S. Both of those two regions are warming on the order since 1970 we’ve warmed over 7°F since the 1970s.

Greg Dalton: Wow.

Elizabeth Burakowski: And for places like New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and the above freezing below freezing line skirts right through that region. And fun fact that a lot of people in New Hampshire tend not to know is that Pennsylvania hosts way more skier visits than New Hampshire right now.

Greg Dalton: I was surprised to see the Pennsylvania rivals Wyoming. I mean I’m a Californian and I don't think of Pennsylvania as a ski state I think of Colorado, Utah, maybe the Northeast, but the sleeper ski state Pennsylvania.

Elizabeth Burakowski: Yeah, and I mean the Poconos are very accessible from the greater New York metropolitan area and that’s a daytrip to get out there. And it is beautiful skiing when you get really good snow out there. My parents actually they learned to ski in West Virginia and so they also are skiing as far south as West Virginia. It's not a huge industry down there, but they’re certainly bolder their weight on the appellations that they do have. But when I think about what's happening in the future, I mean this is kind of a multi-billion-dollar question. Are the people that are living in New York metropolitan area going to make the choice to continue their life as a skier by moving further north as the snow retreats? And right now, it’s looking like a mixed bag. Some people decide just give up the sport altogether. Some folks find another sport to partake in like biking or they also just decide to stay home and spend their money elsewhere. And we’re really not sure how folks are going to respond in the future, except that marginal snow years. So, years like 2015, ‘16, that was a terrible ski year for New Hampshire and Vermont and Maine. That could be an indicative of what we could expect to see in the future. and during that year we saw about a 20 to 30% drop in skier visitation in the state of New Hampshire.

Greg Dalton: You’ve polled people in the Northeast about changing public attitudes about changing weather. What did you find?

Elizabeth Burakowski: Well, this was an interesting study. I was channeling the sociologist in me and trying to figure out what exactly people think about climate change, especially if they’re winter sports enthusiasts. So, if they spend a lot of time outside in winter and they’re skier or snowboarders like snowmobiling, ice fishing, or even just snowshoeing. Wouldn’t they be maybe the person who would notice a change in their environment. So, we asked them that like have you noticed if winters are warmer in New Hampshire today than they were 30 or 40 years ago. And I was fully expecting the winter sports enthusiast to come back and say, oh yes, I have noticed that. Unfortunately, less than half of the respondents overall acknowledge the trend correctly. So, less than half were even willing to acknowledge that it was warming. It had nothing to do with their participation in winter sports. There is no significant relationship with that at all.

Greg Dalton: Political affiliation, did you ask political affiliation?

Elizabeth Burakowski: I was just gonna say that. So, we actually and this was part of the hypothesis that my colleague, my co-author would say, it’s gonna come down to political affiliation I guarantee it. And he was right and of course he’s very well-seasoned in the field. And it was, it was right down to if you are conservative or right-leaning, you are much less likely to correctly acknowledge the scientifically proven warming trend that we’ve seen in our region. If you are left-leaning and more liberal you are much more likely to acknowledge the trend correctly and independents were somewhere in the middle.

The New York Times dedicated two full pages in a recent addition about changes in the jet stream that drive weather patterns in North America and Europe. What are those changes and what do they mean for a person who loves to play in snow or makes their living in a snow dependent economy?

Elizabeth Burakowski: Well, it’s an area of active research. The debate is whether or not we’re gonna start seeing this wavier jet stream. And when we see that type of weather you can end up in situations where very cold arctic blast can make their way much further south. And that's exactly what we had seen during the Texas freeze while the Arctic itself was actually much warmer than average. And it could possibly mean that you end up with maybe one or two more big snowstorms or cold blast opportunities for making snow if you’re in a region that might be having trouble making snow. But we can't count on it, it's too uncertain at this point how this is gonna unfold in the future. When we have this type of sticky weather, so the jet stream getting stuck in this really wavy pattern. That's also what contributes to extreme flooding events. So, if you’re not getting that cold blast you could end up with a lot of rain because you're stuck in a trough where there's a lot of low-pressure systems delivering a lot of rain and it's just that pressure system is not moving. And then likewise anyone who’s stuck in a high-end high-pressure side of that or the ridge they get stuck in a dry season and it's perpetual. So, it’s not great news either way, I think.

Greg Dalton: Volatility everywhere we look. So, knowing all this, are you able to go out there and still kind of enjoy the moment, you know, skiing being in snow or do you go out and say this is beautiful but it’s slipping away. How are you able to hold that moment knowing what you know?

Elizabeth Burakowski: It is tough being a winter climate scientist and it's also tough because I study winter climate where I live. I don't go somewhere far away to study it. It's something that I experienced very viscerally in every winter that I've had since I started doing this work. And I think the first year I started collecting snow data here was actually back in 2011. So, it's been 10 years now that I've been collecting snow data here and I've had good years and I've had bad years. And the bad years have been concentrated towards the end of that time series. And the worst days are when I go out and there's no snow to measure. We still make other measurements while we’re out there. And the best days are still the ones where we have a fresh snowfall when we have those beautiful events that coat the trees and a gorgeous snow fall it’s sparkling in the morning it's quiet as a mouse. And my son also wakes up and he peers out the window and you just get that little kid feeling. I still get it even though I’m like almost 40 years old. I look out the window and I just have this peace and calm. And I think in those moments when we do have that fresh snowfall. The thought of it going away is very much in the back of my mind and I tend to shoo it away if it's starting to creep up on me. Because I do want to cherish it as it's here. We only got to experience it a couple times this winter, but every time it happened, I was out there on my skis doing laps in our trails in the backyard and bringing my son with me towing my children behind me in a sled. I want to embrace every moment I can that we have because I don't know. I mean, based on the future projections for New Hampshire. The coastal region where I live is likely to be snow-free under that worst-case scenario. And it’s a tough reality to swallow and understand that my son might not have white in winter when he's my age.

Greg Dalton: Elizabeth Burakowski is research assistant professor at the University of New Hampshire. Thanks for coming on Climate One.

Elizabeth Burakowski: Thank you so much for having me. It was my pleasure.

---

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation about Weird Winters. Coming up, why a shorter ski season doesn’t just affect powdered elites.

Mario Molina: The 150,000 people who are employed either directly or indirectly by the ski industry are not the people that are able to fly from one resort to another. They're doing it because that gives them the access, because they can't afford a $200-day pass or $1500 season pass..

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

---

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton, and we’re talking about the changing winter climate. People all over the world seek out the snow for sport and physical activity. But few go as far as Kit DesLauriers.

Male narrator: Here’s Kit on her skis from the top of Aconcagua, 22,835 feet up in the Andes. Her descent of the Polish Glacier was a first.

Greg Dalton: Kit is the first person to climb and ski the Seven Summits -- the highest mountain peaks on every continent. As a member of The North Face Global Athlete team, she’s deeply invested in sustaining all that winter provides. She’s joined on the show by Mario Molina, CEO of Protect Our Winters, a group of self-described “pro athletes, dirtbags, and diehards” who advocate for climate action on behalf of winter sports enthusiasts. Of course, Kit DesLauriers is more than just enthusiastic; so what inspired her to take on such a huge and historic challenge?

Kit DesLauriers: I came up with the idea to ski the Seven Summits when I was finishing up my second year on the world freeskiing tour. And I had won the U.S. Freeskiing Nationals, which was held at Snowbird, Utah that year. And so, I got to meet Dick Bass and he was the first person to climb these Seven Summits we’re talking about. And he gave me a signed copy of his book and I read it that spring and that basically birth this next idea. And so, and like Dick, I had already done Denali the previous year. It was kind of a one-off as in not part of my Seven Summits project. And so, I had six left to do. And when I read his book and I picked apart the visuals that I was reading, right, they all seemed quite skiable to me. Yup, that’s how it was.

Greg Dalton: And when you ski down Mount Everest, what did you know about climate disruption at that point? How big was of course climate in your --

Kit DesLauriers: Well, climate is always a factor. So, I like to say, you know, in my career as a ski mountaineer I also have to be an amateur at least meteorologist and above that with the snow scientist. And I pay close attention to my environment always. So, you know, if you think about it, I had to research when all these mountains would be skiable, which is if they are skiable, which is quite different than when most people would be going to climb them. So, I am very much a lifelong student of my environment and I actually studied environmental political science in college at University of Arizona back in the day. And, yeah, so it’s been a lifelong interest of mine. So, it was a big deal and on Everest we were looking for the time of year when it would be most skiable, and that is usually post-monsoon. So, summertime is the monsoon and then the winter brings the cold winds that scour the mountain of snow. So, we were aiming for the September October timeline.

Greg Dalton: Mario Molina, growing up in the highlands of Guatemala. Did you ever dream of skiing down Everest or any of the other tallest peaks in the world?

Mario Molina: No. I can tell you pretty much for certain that I didn't. I actually picked up snow sports relatively late in life, we don't have a whole lot of ski mountaineering going on in Guatemala.

Greg Dalton: And how did growing up in the mountains shape your work? You know, you worked on climate change educating people now advocating kind of organizing in the winter sports community. How did growing up in the mountains point you toward working on climate change?

Mario Molina: Yeah. So, I had the opportunity to live in Ecuador for about 5 1/2 years. And that was really where it became pretty evident to me that glacial recession, particularly in the tropics was happening at a much faster rate than what I thought it would. And looking at glaciers particularly on Cotopaxi in Ecuador which I used to go to relatively frequently made me really start thinking about what are the downstream consequences. And so, thinking about how many of the communities that we visited were dependent on freshwater flow from those glaciers in order to survive, from agriculture to portable water, etc. really highlighted the connection for me between the places that we recreate in that we have the privilege to recreate in and how many people actually depend on those systems for their livelihood. And I'm sure Kit could actually speak to similar situation in the Himalayas where you've got literally a billion people who depend on those freshwater flows from the Ganges.

Greg Dalton: Right. So, to you it’s an achievement it’s an adventure. But to the people who are living it’s survival. Kit, tell us about that because a billion people from the plateaus there get their water.

Kit DesLauriers: Right. Well, water is the conduit for life everywhere. Right here in the U.S. we have that as a major issue and we are looking at the Colorado River not reaching the Pacific Ocean truly anymore. I live right here on the Snake River and I'm watching constantly every year when they allow and then cease to allow however much water flow downstream to agriculture. And then up in the Arctic, I have done some research up there that looks at frankly how much longer we’ll have those glaciers in that U.S. Arctic and the highest peaks which happened to be in the Brooks Range in the Arctic national wildlife refuge. And the estimates right now are that all the glaciers there will be gone in about 100 years. So, that means no more fresh water flowing from the mountains north to the Beaufort Sea in 100 years, which is going to drastically change the landscape there and all the wildlife that depends on it and the people. Not as many people up there. There it’s more of an ecosystem story, but then of course in the Himalayas it’s a lot about people. And you're literally drinking out of the river and washing your clothes in the river and everything. There's a reason that all secret ceremonies happen around those rivers.

Greg Dalton: And Mario Molina, a lot of those things those places that Kit just mentioned might be beautiful and remote for many Americans, North Americans. For people who can't relate to those faraway places will never go there maybe they see them in National Geographic. How do you bring it home to people who say well, I don’t ski or skiing goes away what's it matters to me? How do you bring that home?

Mario Molina: Well, there's probably between 36 million to 40 million people in the U.S. who identify as either skiers, climbers, trail runners or mountain bikers who identify that as a key component to their lifestyle in their physical and mental health. So, I think that the outdoor recreation community is a far larger constituency than many people think in the U.S. And then coupled with that just like Kit was saying the downstream impacts of climate change whether it be forest fires across the West that we experience this last season. Whether it be droughts or increased frequency and intensity of hurricanes. It’s definitely affecting us all of us in the U.S. regardless of whether we, you know, participate in one of these sports or not. I think it's also important to note that Protect Our Winters, we did a study on the economic impact of climate change in the outdoor industry. And the snow sports industry contributes about $20 billion to the U.S. economy every year. And low snow years or shortened winters, that contribution goes down by about $1 billion. So that's actually and that’s supporting 160,000 jobs. So, it's not only effects on recreation, if we're not able to ski or snowboard anymore, at resorts, the least of our concerns will be the activities that we participate in. It’s that at that point, it means that we've crossed a certain threshold where not only there's huge risks to the entire economy some of the very systems that we depend on water, which we've been talking about, but agriculture and infrastructure, etc. are in serious peril. So, to me the amazing insight that people like Kit bring into this conversation is to serve almost as harboring areas that the impacts that we see in the mountains are the first signs of much larger problems that we need to be thinking about in the downstream consequences.

Greg Dalton: We’re talking about the future of winter and outdoor winter recreation with Mario Molina, Executive Director of Protect Our Winters. And Kit DesLauriers, National Geographic Explorer, a member of the North Face global athlete team. Also, she has a memoir coming out on paperback, Higher Love: Skiing the Seven Summits. Mario Molina, we hear later in this episode of Climate One from Geraldine Link, Director of Public Policy with the National Ski Areas Association. I’d like to hear your view on is the ski industry serious about using its power to advance policies that address climate disruption. It's a very elite sport a very white sport has a lot of powerful people are skiers. Is the industry serious about using its power to advance climate action?

Mario Molina: I think the industry has made a lot of progress in the last couple of years in recognizing just the how existential a threat climate change is to its business model. There’s this dichotomy where there's been great work done by NSAA, the National Ski Areas Association and Geraldine to particularly to involve ski resorts and the ski industry in mitigation efforts in mitigating the operations of resorts. And I think that's commendable and really worthwhile. I think the next frontier for the ski industry is to really unite as a political force that lobbies for the right types of policies and the right types of elected officials and the elected officials that will actually make this a priority at the national level in terms of national policies. Because as most of your listeners probably know, you can look at the carbon report. There’s I think it's 25 companies in the world that are responsible for 50% of global emissions in the last 150 years. There are 50 companies that are responsible for 80% of carbon emissions. And I'm pretty sure that neither Vail or Terra or Aspen company are in that list, right. And so, we could do, you know, we could do everything in our power as you can do everything in its power to actually drive their own emissions down to zero, and we would still have a magnificent problem in front of us and not be able to curb it. But if we are able to actually bring the industry together as a powerful force for policy change. I think that then the industry would realize just how much more influential it can be than it currently is.

Greg Dalton: Kit DesLauriers, your thoughts on sort of, you know, there’s a lot of power and privilege among people who ski. Some of them fly on their private jets it’s a very influential part of American society. What role do you see them playing in directing us toward a cleaner energy?

Kit DesLauriers: Well, I see a lot of those people I live here in Jackson Hole so I’m very aware of that demographic. But I’d also just want to mention that the concept of the white elitist for the skiing I do completely agree and understand that historically, that has been the way. I did not actually grow up skiing because my family couldn't afford it. The first time I was able to experience downhill skiing it was like once a year when I was 14 years old. And then I was using borrowed gear and literally skiing in my jeans. And I didn't actually become an expert skier until I had graduated from college and moved myself to the mountains and was paying my own way through life. So I think it's kind of myopic to think that somebody doesn't engage in, you know, mountain climbing or hiking or skiing, that doesn't mean that they shouldn’t pay attention to this. And, you know, where I live a lot of us put a lot of effort into getting other demographics out in the mountains experiencing them. I think that's actually a big push that's happening in our country right now is we’re seeing a lot more people of color and people of different socioeconomic backgrounds being given a hand to get out there and support it and uplift it. And so, I'm happy to say that from my perspective in the industry I see that demographic shifting and I'm encouraged. And that also actually brings me a bit more encouragement around this entire topic of climate change. Because I do think it's the youth and it's other people who have somewhat been underrepresented who care a lot. They think about their lack of opportunities going forward in life should they it’d be more difficult to protect their home from wildfire or get water or get out in adventure and experience, you know, what it means to like get outside and have opportunities for grit and determination and character building.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, I hear your point about sort of the typical profile of skiing there are structural barriers, economic barriers, class barriers, people don’t feel comfortable all sorts of reasons about access for why the sport has been that way. I know there are efforts to change that. Kit DesLauriers, you took your children to the Alaska National Wildlife Refuge when they were five and seven years old, that was about six years or so ago. How will skiing and outdoor winter sports change in their lifetime?

Kit DesLauriers: It has changed a lot like my kids are they love skiing and they’ve been skiing a ton this winter because they’re at home for school and so they can. And it's interesting like we haven't, well, we had a great winter, you know, where we really are seeing a lot more dynamic weather pattern changes. We had a great winter and now it's just been high and dry for a few weeks and that's all that's in the forecast going forward. So, you know, they’ve been spoiled because here in Jackson Hole we get great snow. And so, they're just looking at it now like seriously, it's like it's warm and it's melting and there's no snow in the forecast literally until the end of the ski season. And that's been the pattern, which is what climate change is its weather patterns over time. For me, I have my favorite time to ski the big peaks here is in the deep of spring. So, when the resorts have closed its April and May it’s when it's safest to get up high because we’re having these diurnal temperature changes that you know mean that the snow is melting during the day and freezing at night and it’s becoming a bit safer. You can move really fast because we’ve got like 7000 vertical feet to cover to get to the top of the big mountains here like the Grand. And I just love it it’s just my favorite thing that time of the year when the valleys are green below and the snow still up high and the climbing is a bit more technical. And anyway, that season has pretty much disappeared in the last several years. And when I moved here 20 years ago, that was my go-to. And now I'm lucky if I can get two or three days the spring and up high and in safe conditions. Because I literally wake up at 1 o'clock in the morning because I usually have to leave at three and check the weather and we didn't have freezing temperatures even at 10,000 feet overnight. So, it's changing drastically. I think that the ski seasons will be cut shorter, but not as I talk about my kids that's the short answer but then the longer answer is really what's happening with the watersheds over the summer and the temperatures for the wildfires.

Greg Dalton: Mario Molina, Kit’s comments about shortening seasons is the stress on snow makes me think about how many ski resorts have gone out of business because of the stress or how many will go out of business because there’s just not enough snow and they can’t afford to make it by using fossil fuels to freeze water.

Mario Molina: Yeah. That’s reality and it's not something in the far future it’s something that's happening right now. I think what we’re seeing in the ski industry is a conglomeration of ski corporations that are able to stay afloat because they have debt leverage or they have the resource to do so. And then a lot of the smaller family-owned or individually owned resorts going out of business or being necessity being acquired and they’re shutting down. I think there's some of the big companies like Altera have been really conscientious about their business model and realized that they are going to change the way that people think about skiing from predictable winter season at my local winter resorts that I can start November 27th and ski through March 15th to those that are able to afford and have access to it being able to say, no, if I actually want to ski I’m gonna have to travel to where the snow is. Much more like surfers chasing in the summer. And the 150,000 people who are employed either directly or indirectly by the ski industry are not the jet setters are not the people that are able to fly from one resort to another. They are the people that take on, you know, local waitressing jobs and help take care of the hotels and small business owners for whom in exchange they get -- they’re the people, the lift operators, they are the people that actually make all this happen. And they're doing it because that gives them the access because they can't afford a, you know, $200-day pass or $1500 season pass. But that is the backbone of the industry and that backbone is at risk from climate change as well. And I think that too often we forget to talk about the people that make skiing possible in the industry and the hard-working people of the industry when we characterize just the skiing community as a whole.

---

Greg Dalton: You're listening to a conversation about the Future of Winter. This is Climate One. Coming up, more with Kit DesLauriers and Mario Molina, plus: the view from inside the ski industry.

Geraldine Link: I love talking about snowmaking because there are myths and there are facts when it comes to snowmaking. And I like nothing better than to try to set the record straight there.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

---

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. We’re talking about the Future of Winter with Kit DesLauriers, Skimountaineer and National Geographic Explorer, and Mario Molina, CEO of Protect our Winters. In 2018, Outdoor Retailer, an industry tradeshow, moved from Utah to Colorado, to protest Utah's attempt to rescind Bears Ears National Monument on lands considered sacred by Native Americans. Many ski resorts are on lands leased from the federal government. Mario describes the efforts of Protect Our Winters to include indigenous American voices, in the campaign to conserve lands they once occupied.

Mario Molina: We really work to protect the intersection of public lands and climate change and the interests. And so, and that a lot of times has happened as you’re mentioning in indigenous lands. So, we will always defer to our indigenous partners on the ground in terms of messaging and in terms of the importance that it has to do their own lands rather than try and speak for them. I think that there's also this parallel path there is the moral imperative to protect these lands and to honor the original inhabitants of lands. And then there's also the very pragmatic reality of the marketplace and how what you particularly in the last year what we've seen is that it's simply not long-term viable business model to continue to exploit these lands for and squeeze them for the last little bit of oil and gas that we might get out of them. And I think the recent really failed lease program in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge coming out of the Trump administration is proof of that. It was touted as this major economic potential economic boost and it was touted as being the last big frontier for exploration and there are being three bids for, you know, for half of the lots that were actually open for the lease and drew less I think it was $14 million, which is really pennies when we think about the scale --

Kit DesLauriers: It was supposed to draw 1.8 billion. If I could interject.

Mario Molina: It was supposed to draw 1.8 billion, yeah. So, it’s 1/10 or 1% of what it was projected. So, and that's because there was, you know, it’s a consilience it’s one the volatility of oil prices and the drop in oil prices in the last year and a half. The reticence of the financial sector to lend money for this sort of explorations and the high-risk profile of these types of endeavors and also the change in policy. And I think coming with the new administration that’s why for us at POW, one of the most important things that we can all do is to participate in our democracy. Because we see that elections have consequences and policies have consequences. And now I think that the culmination of the market the volatility of oil price and the incoming policies of the Biden administration all coalesced to make ANWR just not an attractive prospect for oil development.

Greg Dalton: As we look at this, you know, think about it’s pretty dark you know the trends toward less snow that kind of shrinking industry shrinking sport. Where do you find hope and promise as you think about this where do you see bright spots and say, either find beauty even when there’s maybe some decay or you find progress that keeps you going, Kit?

Kit DesLauriers: Well, I’m gonna just share a quick story. when I was up in the Arctic refuge in 2012 doing some glaciology work. The PhD glaciologist I was working with then, Matt Nolan explained to me that on this study glacier he had been working on for 15 years, he done ice core samples. And he literally was able to see in these ice core samples the impacts, the positive impacts if you will from the Clean Air Act. So, there were less emissions happening up in northeastern Alaska after the Clean Air Act was established. And so, the parallel I'm going to draw there is legislation. Because we Americans are fun seekers. We are certainly going to take the easy path down. It's just evidence by people wanting to ride chairlifts up and ski down and whatever you know eating tortilla chips and whatever else, right. We’re gonna take the easy path. So, if we actually can get some legislation through that will help us change our habits and our patterns around energy use and emissions. Then I do believe that that’s the shining light.

Greg Dalton: That's pretty cool. You can actually see policy in the ice cores. You can see tangible change from a moment in time. Mario Molina, what gives you hope and inspiration as we look at shrinking, changing winters?

Mario Molina: The fact that it's right now as we speak it is dumping outside my window. And I think it's really important to not get so dismayed and overwhelmed by future prospects that we forget to enjoy appreciate and be grateful for what we have right now and that that is what we want to protect regardless of what the process might look like. So, that's one. And then the other is there's really an awakening in America and in the world and starting with young people, but I think across all sectors of society. It used to be that even though we knew the numbers and we knew the science climate change wouldn’t make it into a presidential debate. And that was just four years ago. And now we have climate change at the top of pretty much every policy discussion that’s happening in the country in one way or another. And people across both sides of the aisle recognize and are supportive of it, and it's a matter of coming together and making it a priority. So, I actually think that that is one of the issues on which we agree on the most and it's a matter about how do we actually go about putting the solutions in place. And to me, that is really encouraging.

Greg Dalton: Well, thank you for a fitting end. Mario Molina, Executive Director Protect our Winters. And Kit DesLauriers, National Geographic Explorer, and member of the North Face global athlete team. Thank you for sharing your stories and insights on Climate One.

Kit DesLauriers: Thank you, Greg.

Mario Molina: Thank you, Greg. Thank you for having us.

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to Climate One. A story last year in Mountain Town News said the ski industry is becoming more assertive in talking about climate disruption. The reporter, Ellen Best, credited my next guest with bringing more urgency to the industry: Geraldine Link, Director of Public Policy for the National Ski Areas Association.

Geraldine Link: We’ve actually been working on climate change advocacy since the year 2002. And NSAA partners with the Outdoor Industry Association and Snow Sports Industries America. Together, we are the outdoor business climate partnership and we represent the $887 billion outdoor industry on climate. And we do events and activities and lobbying in Washington with members of Congress on solving climate change. So, just to give you an example. Last year we participated together in the lead climate advocacy event that CERES put on also Citizens’ Climate Lobby was involved as well and other organizations that are like-minded. And we together had a series of meetings with members of Congress and we had I think all together that day. There were 300 companies doing 88 separate meetings with members of Congress on climate. So, we will come together for an event like that and try to bring a stronger voice through the entire outdoor recreation industry on solving climate change. We also --

Greg Dalton: Let me just jump in there Geraldine and ask like what is that conversation like? So, I think of states like Colorado and Utah where fossil fuel extractions are a big part of the economy. Also, skiing is a big part of, you know, obviously Park City in Colorado. So, what is that conversation like with the legislator in a state that where there's ski but there's also a lot of fossil fuel extraction what’s that conversation like?

Geraldine Link: So, that’s a great question and I'll just share with you a story. So, last year during this meeting we were paired up with Representative John Curtis, a Republican from Utah. And one of the things that that really struck me in talking with him is he got right to the point at the beginning of the conversation and said, look, we know we have to solve climate change. He said, I come from an energy state but also in my state, terrorism is a huge economic driver. And so, outdoor recreation really matters to my state. My constituents, a lot of them are skiers and riders. And so, he came right out of the gates in that conversation to connecting with us and saying we have to work together to solve this problem and just acknowledging that right from the start. And so, as a result of that conversation that we had with him last May, we reached out and said, would you be willing to be the cochair of the Congressional Ski and Snowboard caucus? So, we already had a Democratic chair representative Ann Kuster from New Hampshire and Representative Curtis said, yes, I'm up for that I will take that on. And not only is he the cochair of the ski caucus but in January he formed a new caucus, the wildfire caucus with representative Joe Neguse from Colorado who is a Democrat. So, you know, when you look at for example, Boulder County is where you know his home base is and John Curtis from Utah both of them have said you know our constituents might have different values on some level, but they value outdoor recreation. And we also, you know, our state economies are very dependent on outdoor recreation. So, we have those things in common we’re also both threatened by wildfire and that's another part of climate change besides snow that's really important to the ski industry. So, I see just huge progress there and promise. And honestly it gets me pretty fired up because I have spent a couple of decades talking to members of Congress in Washington about climate change, and it seems like we've been moving at such a glacial pace for so long in trying to get solutions rolling. And just in the past year I’ve seen huge change and willingness to come to the table to say yes this is an issue. Yes, we need to solve it. Let's have a conversation and let's see what our common ground is.

Greg Dalton: One way that ski resorts respond to variable weather is by making snow. And some people see ski resorts as energy hogs because the irony of burning natural gas to make snow because of a warming climate that brings precipitation sometimes in the form of rain, more than snow. So, how do you address that and there's incentive that every ski resort has an incentive to do what's best for them in their area and that can be makes snow burning fossil fuels.

Geraldine Link: Yeah, and I love talking about snowmaking because there are myths and there are facts when it comes to snowmaking. And I like nothing better than to try to set the record straight there. So, just looking over all at energy uses a ski area is not the energy hog that it’s purported to be. So, if you look at your average ski area it represents about 10% of the energy use of a mountain community. And then if you dive in a little deeper and look at snowmaking. Snowmaking represents 20% of ski area’s energy use on average. So, when you compare it to buildings and lifts which theories are running much more frequently or using energy, snowmaking comes out third in that equation. And another thing I like to point out about snowmaking as well is that we have invested heavily in more efficient snowmaking in the ski industry and energy efficiency. We also have ski areas and states ski associations who are working with their utilities to green the grid. So, they are engaging on decarbonizing the grid. So, I think it's important to keep all of those things in mind when you're talking about snowmaking. Snowmaking also helps take away some of the bite of a warming climate. And when I say that, you know, ski areas, they invest a lot in water resources and also water infrastructure. We make snow and that's like a frozen reservoir. So, that snow that snowpack that we make stays around through the late spring early summer months. And so, it actually slows down the runoff. And I think that's really important to know. Also, snowmaking is a non-consumptive use of water. So, 80% of the water that is used for snowmaking returns to the watershed.

Greg Dalton: Right. So, what’s the future of skiing look like? Is it consolidation in the industry where there’s a few large companies that own resorts, Vail seems to be buying up everything. And so, a certain number of skiers will be able to fly to Utah or Colorado or British Columbia where there is good snow and zip around perhaps in their private jets and not, you know, there’ll be always good snow for them somewhere. But it will be a much smaller narrower ski industry in 10 or 20 years.

Geraldine Link: Well, you know, I can tell you what we’re seeing right now. And I think it's really important to talk about the pandemic and what that has done to recreation in this country, especially where I am in the West what I see what I witness. And so, we have seen huge demand for outdoor recreation through the pandemic. And I think that people are very much more flexible in their work schedule today than they were a year and a half ago. And so, we have been seeing all kinds of changes in the way that people recreate in the outdoors as a result of this pandemic. And it's not all bad, right? Some of the things that we’ve learned in the past year we will take forward with us in scary operations. So, I see smaller resorts thriving when people, you know, instead of flying to the Virgin Islands, they are looking for local recreation. And part of that is from the pandemic. Some of that is gonna stick it’s not gonna change and we’re not gonna go back entirely to the way things were pre-pandemic. But I see a place for those smaller ski areas that’s where people learn to ski and ride. It tends not to be at a big destination resort but those local ski hills. And right now, we’re seeing very strong demand for outdoor recreation for skiing and it's really been a salvation for many people this past season. And kudos to the frontline employees of ski areas who made this happen they are truly appreciated and we couldn’t have done this without them. So, I see the ski industry as an incredibly resilient industry and they’re resourceful they changed the business model when they have to and I see a very positive future for skiing.

Greg Dalton: Great. Geraldine Link, Director of Public Policy with the National Ski Areas Association. Thanks for coming on Climate One.

Geraldine Link: Absolutely. Thanks for having me.

---

Greg Dalton: You’ve been listening to a Climate One conversation about the changing winter climate. You can hear more by subscribing to our podcast on Apple, Spotify or wherever you get your pods. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. It really does help advance the climate conversation.

Greg Dalton: Sara-Katherine Coxon is our Senior Producer. Kelli Pennington directs our audience engagement. Tyler Reed is our producer. Steve Fox is director of advancement. Devon Strolovitch edited the program. Our audio team is Mark Kirchner, Arnav Gupta, and Andrew Stelzer. Dr. Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum, where our program originates. [pause] I’m Greg Dalton.