Should We Have Children in a Climate Emergency?

Guests

Daniel Sherrell

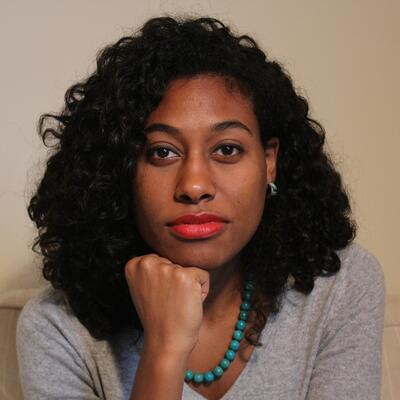

Irène P. Mathieu

Virginie Le Masson

Seb Gould

Summary

Listener Advisory: This episode contains some content related to a suicide. If you or someone you love is thinking about suicide, the National 24-hour Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255.

Climate disruption features in the headlines nearly every day, moving deeper into our personal lives. In these uncertain times, how do we weigh the decision of whether or not to bring more children into the world?

Author and climate activist Daniel Sherrell wrestles with intergenerational angst in his new book, Warmth: Coming of Age at the End of Our World. In the book, he refers to climate disruption as the “Problem,” rather than by more conventional climate terms.

“For a long time I felt sort of dissatisfied with climate discourse in this country. And when the phrase ‘climate change’ was evoked, it was immediately shunted into this pigeonhole my brain, as I think it is for many lay people paying attention to this problem, that's like, ‘it's the purview of scientists, it's a very bad current event that is sort of happening up there in the ether, in the headlines,’” Sherrell says. “And by choosing never to name it in the book I wanted desperately to break it out of its little narrow environmentalist pigeonhole as if it were just like one more issue on the long bucket list of issues...but was, in fact, a massive force that was going to change everything about how we live on this planet drastically over the coming centuries.”

Sherrell writes about how his father, an oceanographic researcher who worked in the Antarctic, struggled to discuss climate change when Daniel was younger. In subsequent years, Sherrell says they’ve been able to discuss it with more emotional honesty.

“And I think figuring out how to do that metabolism of this crisis into something you can hold in your hand and examine and actually establish your own relationship with is an incredibly difficult task, and I also think one of the chief ethical and political responsibilities of what it means to live in the Anthropocene, especially as a young person,” Sherrell says.

Sherrell’s book is written to an unborn future child of his, and follows his struggle to consider whether or not to conceive a child in the climate crisis. He’s not the only one struggling with this decision.

Climate One talked with three people deciding whether or not to have biological children in the climate emergency about their reasons and process. Virginie Le Masson is a climate change researcher at the University College London.

“On the emotional side I know I want to have children, I always wanted [to], but on the rational side, I don't know,” she says. Her concerns include environmental degradation and the moral implications of bringing a child into a world who may suffer.

Physics teacher Seb Gould says he and his partner have decided not to have biological children, for reasons including climate change, environmental resource use and unfair systems around child-rearing, like the fact that women get more paid leave and are thus expected to do more of the work.

Pediatrician Irène Mathieu recently had her first child after a couple years of weighing the pros and cons. “I think for me really following my intuition for a choice this big made more sense than trying to settle a rational or ethical debate because I think that it's kind of an impossible question,” she says. “I'm more interested at this point in shifting my energy and my focus to bigger policy issues rather than my own individual decisions, which are really kind of small fish when it comes to the actual impact.”

Related Links:

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. Climate disruption is in the headlines nearly every day, penetrating deeper into our personal lives. How do we process the meaning of that?

Daniel Sherrell: I actually think what the climate crisis demands of us is holding to each other tighter and gripping faster in solidarity and love rather than saying goodbye to each other in death or in emotional isolation.

Greg Dalton: And in these uncertain times, how are we weighing the decision of whether or not to bring more children into the world?

Virginie Le Masson: On the emotional side I know I want to have children, I always wanted but on the rational side, I don't know.

Irene Mathieu: You know, maybe there is no answer right answer to this ethical debate. But maybe just your certainty and your deep feeling that you are meant to mother in this way is enough to answer the question and then it's about how you do it. (:11)

Greg Dalton: Should we have children in a climate emergency? That’s up next on Climate One.

Greg Dalton: How do we plan for the next generation to inherit a society destabilised by our addiction to fossil fuels? Climate One’s empowering conversations connect all aspects of the climate emergency. I’m Greg Dalton.This summer the climate crisis seems to be unfolding faster than ever --with catastrophic floods, huge wildfires, and killer heat. Climate disruption is here, growing more intrusive every day. How do we bear the weight of these changes, and process our fear for what is coming for us, and our children? Author and climate activist Daniel Sherrell wrestles with intergenerational angst in his new book, Warmth: Coming of Age at the End of Our World. He opens with the story of prominent civil rights lawyer David Buckel. Sherrell says after retiring, Buckel became a “titan of composting” in and around Brooklyn, sequestering tons of carbon every year.

Daniel Sherrell: And then out of the blue several years ago he killed himself by setting himself on fire in Prospect Park in the wee hours of the morning before most people were around. If you read his notes and his writings before he took his own life, which are scant, the sense you get is of a man who was increasingly despairing around climate change and cared about it passionately and was doing his little part by sequestering all this carbon and sort of a Herculean effort when it came to local composting and still saw that as a drop in the bucket. Suicide is a very difficult topic and there are many reasons that contribute to an individual’s choice to take their own life. But the sense I got when I found out about his death was first of all, in a sort of strange way it gave voice to some of my own anguish about the climate crisis. I would be lying if I said I hadn’t considered myself you know, suicide as a political act. You know in my most despairing moments when I felt like my God like what tactics are there left to us what cards do we still have left on our sleeves, I had contemplated this thing. Not seriously, never seriously, never actually making plans, but it was a thought that had crossed my mind as I sort of grappled desperately to figure out, to see a light at the end of the tunnel.

Greg Dalton: And your mother said, don’t do it because you would only -- right? Your mother implored you not to do it.

Daniel Sherrell: Yeah. And my mother was deeply right and she said, she is a wise and wonderful woman and it’s never something I would do. And I don't I actually think what the climate crisis demands of us is holding to each other tighter and gripping faster in solidarity and love rather than saying goodbye to each other in death or in emotional isolation. So, the first reaction to his death was like oh my God, somebody has actually done it, you know. And the second reaction was God, he must have been so lonely, you know, and I felt that myself you know this feeling of real heaviness around the climate crisis and not seeing cultural avenues around me to process it. And like climate grief still being a sort of illegible emotion in the public sphere and when we talked about this thing called climate change which I never refer to by name in the book for very deliberate reasons it was often in the language of parts per million in the atmosphere or the IPCC reports or the COP conferences.

Greg Dalton: Throughout the book you referred to climate disruption as the problem with the capital P which reminds me of the troubles in Northern Ireland. You rarely use terms like climate change climate emergency, why did you make that choice to not use I guess the technical language that climate change evokes?

Daniel Sherrell: I think for a long time I’d felt sort of dissatisfied with climate discourse in this country. And when the phrase climate change was evoked, it was immediately shunted into this pigeonhole my brain as I think it is for many people, many lay people paying attention to this problem that's like, it's the purview of scientists, it's a very bad current event that is sort of happening up there in the ether, in the headlines. And it doesn't really have much to do like how I’m tucking my kid into bed at night or how I'm thinking about caring for my aging grandparents. And by choosing never to name it in the book I wanted desperately to break it out of its little narrow “environmentalist pigeonhole” as if it were just like one more issue on the long bucket list of issues alongside, you know, tax reform and saving the whales and you know, lead poisoning on our pipes. But was in fact a massive force that was going to change everything about how we live on this planet drastically over the coming centuries. I wanted to be able to like grapple with the full magnitude of that and I felt the phrase climate change was actually thinning in that way. And I also wanted to de-familiarize it for people in that old writerly ploy of making something that people think they knew and have sort of internalized already and put in a certain compartment and that their brain making it fresh again so that a real encounter and a real spiritual, emotional and philosophical encounter can actually occur. Because at the end of the day I don't actually think that what we usually refer to when we say the climate crisis which is mounting greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere, leading to a very sick planet, I'm not sure if that's a problem so much as a symptom. And it's a symptom of the very sort of blindered methods of thought and attention we applied to the world around us under late capitalism, in my opinion.

Greg Dalton: Right. So, climate as a symptom rather than a cause. And we talked on Climate One yeah about the capitalism and some of the individualistic and extraction and even colonial mentalities that underlie a lot of that. Explain your resistance to the concept or identity of environmentalism because you write it comes from a root word of environ, which means around, kind of separate from us.

Daniel Sherrell: I think back to my time there’s a chapter in the book where I describe the opportunity I had to walk a traditional songline with an aboriginal tribe in the Northwest of Australia who had just saved that songline from encroachment by the natural gas industry that were trying to build a plant in its middle. But I mention that just to say that I think when talking to folks out there in the Goolarabooloo clan the concept of environmentalism is just like, you know, that makes no sense to them. It’s sort of like saying, oh I subscribe to reality-ism, you know. It’s like the environment is such an all-consuming concept as to be in such a thing that is woven through the absolute texture of reality that to sequester it in its own concept and then anoint with an ism is quite strange because it has a distancing effect. And I think you know in the West, because of that rupture, suddenly that thing starts to suffer because of all the behaviors that rupture allows. And then we’re like, oh no, we have to save the environment as if the environment is not us, you know, it’s a very weird thing. And I also associate it with like multiple decades of the environmental movement being mostly about recycled handbags and CFL light bulbs which I think was a very corporate-friendly, and ultimately unvisionary instantiation of the thing that we’re not trying to build in the climate justice movement which I think is a lot broader.

Greg Dalton: So, we define the environment we separate from the environment and it’s detached from us. Then we realize it's at risk and we need to reconnect with it and understand that we are a dependent and part of it. You write that fossil fuel is everywhere though rarely seen. People pump gas into their cars, but they don't see the gas they smell it. I thought that was really interesting. Can you say more about that sensory relationship?

Daniel Sherrell: The infrastructure undergirding the climate crisis is in many ways quite abstract, right. We talk a lot about fossil fuels but very few people have ever held a lump of coal or seen oil sluicing through a pipeline. The infrastructure of that and the very real things that we’re digging up from the ground which are basically the guts of the earth that we are dredging up and pumping through our cars and our buildings. All of that’s been hidden from us and so there's a way in which the whole the etiology of the problem is just incredibly abstract for people. And I think that contributes to us having a hard time wrapping our heads around it because both the impacts are abstract in some ways. I mean in many ways they’re very real, but they have to deal with parts per million in the atmosphere and probabilistic assessments of how likely extreme weather events are.

Greg Dalton: They’re indirect. It’s not like, you know, if someone pulls the trigger on a gun there’s a consequence, a human consequence. Whereas in climate, you drive a gasoline car and some place, some storm, some bad things happen in a different time and place. So, there's again that disconnect between what we do and the impacts of it.

Daniel Sherrell: Totally. And I think that's why there is much that is demanded of us through policy change and organizing in these next few decades, a tremendous amount. But I also think there are many ways in which we have to sort of like update our culturally normative philosophies about what causality is, about who's responsible for who and about the kinds of things we pay attention to. Because it is the climate crisis makes incontrovertibly clear that the level and breadth of interdependence not only between humans when you know me pumping gas in my car in Washington DC affects a farmer who’s trying to raise a crop from increasingly saline soil in Bangladesh. And not only between humans across time like my pumping gas in my car right now or us succeeding or failing in passing the big reconciliation bill that’s on a knife’s edge in Congress right now will have material impact in people that live probably five or six generations from now. But also the interdependence of the natural world, you know, thinking about if environmentalism is the thing that sees the polar bear on the ice flow and says that’s so sad we should save that polar bear, when what’s increasingly seems like the right attitude is like we’re not separate from that polar bear that it is the canary in our own coal mine.

Greg Dalton: And that’s what indigenous people inherently know. You write that there was no single eureka moment for you to become an activist. Rather, it was slow entrapment. How did that unfold for you and how did you discover your own responsibility or complicitness?

Daniel Sherrell: Yeah. Well, I grew up in a sort of unique position with about the climate crisis. My father is an oceanographic researcher at Rutgers University, he would spend multiple months every year when I was growing up on research voyages to the Antarctic. Basically, you know, doing very esoteric research about how metal particulates in the ocean affect plankton blooms and a lot of other stuff.

Greg Dalton: But drilling ice cores reveals the composition of past atmosphere that’s very direct fundamental climate science.

Daniel Sherrell: Yes, exactly. So, he would not describe himself as a climate scientist but he definitely works with many and he's adjacent to that field. But he would come back and you know, with a little bit of worry in his voice say like, that's not the same continent I went to a decade ago. And because of the albedo effect and other things, you know, the poles are warming much faster than any other place on the planet. So, global warming as a concept was introduced to me extremely early in my childhood and then I had nowhere to go with it.

Greg Dalton: You write that it was difficult for your family to talk about that your dad would say these things and almost like you didn't know where to pick up the thread, were you intimidated or feel inadequate compared to him? I found this part of your book fascinating because I wrestle with that in my own house like how much do I talk about it do I not, do I withhold and how much intensity can the other person handling carry them? So, how did you receive that as a young man?

Daniel Sherrell: I think my father really grappled with those questions, but I also think in the years we’re talking about which was the late 90s, early aughts like the strangest thing for me was based on what my father was telling me I didn't understand why everybody I knew was talking about this all the time. Like it seemed like given what I understood about the magnitude of what he was saying. It just seemed like surreal that it seemed like this little secret between us. I didn't see referred basically anywhere else.

Greg Dalton: Socially constructed silence.

Daniel Sherrell: Exactly, exactly. And I think even for my father like I think culture creates technologies and avenues of feeling you know, like I feel like even subsequent years my father and I have been able to talk much more vulnerably and emotionally about what's happening to our planet. And I think some ways like the culture has shifted under his feet, such that he now has words and frameworks with which to fuel the feelings evoked by the facts that he helped produce. But back in the 90s it was just like the surreal thing that we didn't know where to take it. And I think that was a lesson for me in retrospect, that even somebody who knows all the science, even somebody who's incredibly emotionally available and my father and I have a very close relationship. Even that person has a hard time getting under the surface of the climate crisis in a way that it feels not this abstract current event hovering over your head, but like a personal reality that is going to affect you and your family for the next hundreds of years. And I think figuring out how to do that metabolism of this crisis into something you can hold in your hand and examine and actually establish your own relationship with is an incredibly difficult task, and I also think one of the chief ethical and political responsibilities of what it means to live in the Anthropocene, especially as a young person.

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation with author and climate activist Daniel Sherrell. If you missed a previous episode, or want to hear more of Climate One’s empowering conversations, subscribe to our podcast wherever you get your pods. Coming up, Sherrell says creating cultural avenues for people to process climate grief and anxiety can lead to more action, and help us feel better:

Daniel Sherrell: Which is why it’s really important that we like, you know, do the work to be able to process what we’re gonna go through for the next century together in public, rather than alone doom scrolling on our Twitter feed.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton, and we’re talking about processing the emotional intensity of the climate emergency with Daniel Sherrell, author of the new book Warmth: Coming of Age at the End of Our World. Sherrell writes about experiencing a delay or disassociation from his feelings about climate collapse. One concept he explores is the difference between knowledge and realization, a distinction that I find fascinating.

Daniel Sherrell: You know, when you go to a meditation retreat for instance, they’ll kind of give you the knowledge up front whatever the knowledge may be: everything is impermanent, the self is an illusion. They hand you the truths right there on day one. And then you spend literally the rest of your life in a practice that is simply trying to realize the truth whose propositional content you knew from the very beginning. But knowledge is sort of this shallow and kind of binary process. You know the facts or you don't, it’s like you switch on the light switch. Realizing is a practice and it takes a long time. And I think you know when Al Gore and you know God bless Al Gore I wish I would chop off both arms who have made him president in 2000 I think we’d be in very different place, but this often very Western conflation between knowledge and realization was what undergirded An Inconvenient Truth. Because he was like if I just show people the graph if I show people the hockey stick and give them the PowerPoint to the facts are right and it's persuasive, that is equivalent to doing this sort of emotional and philosophical and political work that will get us out of this situation. And, you know, the past few decades have shown that clearly that's not the case that there’s another ingredient involved.

Greg Dalton: As a white man you like me have not grown up enduring what you call “the violence of structural racism” as you write in the book. You also mentioned that you feel guilty for not being really vulnerable to the direct impacts of burning fossil fuels. How does your privilege inform your work as a writer and activist?

Daniel Sherrell: I think my relative privilege is the thing that embeds in me a deep responsibility to actually take on this crisis. Because we live in a country and an economy where you know it runs on desperation in many ways. Hopefully our gradual move away from neoliberalism will lessen that but there are a lot of people that just have a hard time making ends meet in this country. In a way it’s a privilege to have all the lower rungs of my Maslow's pyramid covered, don't have to worry about food, don't have to worry about housing, don't have to worry about severe sickness or disability. That leaves me with a lot of extra capacity. And you're damn right and when you use that capacity to try to make lives of the privilege that I enjoy life of basic dignity and at times leisure accessible to everybody. If that's not what I'm using my privilege for I don't know what it's for.

Greg Dalton: And you write that you’re surprised how few people are involved in doing that who are comfortable as you are. In New York City all it takes is one large meeting room to accommodate a good portion of the millennials who make a living trying to forestall the apocalypse. How do you handle and think about the apathy among your peers and neighbors?

Daniel Sherrell: I actually don't I wouldn't call it apathy. I want to be generous to people here. I think for a lot of people it's overwhelm. It’s in fact, I think a feeling that is too deep-seated and too isolating to even really be talked about. And so, people bury it and move on with their lives. I don't know if that's true for everybody, but that’s my most generous reading. And I think creating cultural avenues where people can feel safe bringing these feelings to light is actually going to lead to an increasing outpouring of like people not acting as if they're apathetic and hiding their anxiety or their grief behind sort of like blindered walls of feeling. Which is why it’s really important that we like, you know, do the work to be able to process what we’re gonna go through for the next century together in public, rather than alone doom scrolling on our Twitter feed. But I also think that like you know ultimately, we’re never gonna get a majority of people active in the climate movement, just like in every important social movement in the history of the world. I think the people I worry more about obviously are the active obstructionists like the very few corporate executives and the politicians they've purchased who are literally the only people on the planet incentivized to watch the world burn and the power they still wield over our democracy. So, I think a lot of people feel guilty about the climate crisis, A, because they’ve been suckered into this framework that if we just screw in the right light bulbs or if they are just better recycling then it’ll be solved--

Greg Dalton: Yeah, thanks to the Crying Indian and all that.

Daniel Sherrell: Yeah, it’s, you know, and it’s a very clever move by the fossil fuel industry. It dovetailed with sort of like the Puritan ethic, it dovetailed with our identity as individual consumers under late capitalism. And it left them completely off the hook because what actually has to happen is we need to regulate, build the political power to regulate those corporations into the ground because they are sociopathic actors. So, on the one hand I like if anything, I try to alleviate people of their guilt because I think the fossil fuel industry wants you to feel guilty. They want you to feel horrible at yourself because that bedrock is a very bad bedrock from which take political action.

Greg Dalton: Your group was ultimately successful helping to decarbonize New York economy over the next three decades. How did that make you feel and what needs to happen next?

Daniel Sherrell: Well, on the one hand I feel proud of that victory. The Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, as it was ultimately named is still one of if not the most aggressive climate and equity policies passed at the state level in the country. It wasn't just the climate, people working on this. In fact, it wasn't the climate people leading on this. It was environmental justice communities, it was community organizations representing low-income communities of color. It was labor unions. We actually had to like form alliances with people we hadn’t always seen eye to eye with in order to build the political constituency that could actually wield enough power to get a bill of this magnitude passed. And I think there's a real beauty in that sort of coalition building. It was you know our target the person we are trying to convince to give his imprimatur to this bill was of course a certain New York governor who is now going down in political flames. You know, the process of passing this bill was like he resisted and resisted and resisted us for a year and a half and then when he finally felt the political headwinds were too much he got in front of the parade and gave the bill his own name, which were like you know were fine. If your ego is gonna be the thing that gets us across the finish line, fine. But I’ve been thinking a lot, you know, with the scandals recently about how that administration governed and how absolutely backward it is and not up to the challenge of the climate crisis because they were essentially a status quo body. And when you push them on something ambitious, you know, I would get calls I remember one instance getting a call from his Chief of Staff, Melissa DeRosa, and, you know, these people don't even wait for you to say hello, they just start screaming down the phone at you. You know, the governor is already like leader in the nation on climate change all the stuff and just basically trying to use an animal fear to like beat you into submission. And there was a basic resistance to any visionary change in the status quo that we had to build a lot of power in order to overcome.

Greg Dalton: This book is addressed to a future unborn child of yours and follows your struggle to consider whether or not to conceive of a child, which is the theme of this episode of Climate One. The prose is bittersweet, heartfelt and full of longing. It really resonated with me as a dad with two young adults. Where do you sit on the idea of having a child at this moment?

Daniel Sherrell: I think a lot of people ask me that and I don't, I haven't landed on a firm yes or a firm no after writing this book. Mostly because this book uses that question as a way into thinking about the climate crisis, but I didn't feel like I wanted to land on a take at the end. And obviously also this will not be a unilateral decision; this will be a decision made with my partner. But I think part of my impetus for writing the book was that you know the deeper I got into thinking about the climate crisis, the more it became clear to me that for a while and sort of without any conscious foresight on my end I had like this framework of wanting to be a father like thinking that that would be a beautiful process and also feeling deeply ambivalent about that prospect given what I knew about the scientific projections. And the more I thought about that being clear that while I couldn't in good conscience, bring a new person against without their consent into this sort of world if I wasn't ready with like a physical document that I could hand them to start the conversation and hold each other in the conversation about the world that they’ve been brought into. And that if I couldn’t write that document and have it feel emotionally honest, then I couldn't have a family. So, this was both like a preparation and a test for myself writing this book. It’s still quite possible that I won't have children for a variety of reasons, but I think, do I think there's a normative answer to this for everybody? Absolutely not. I think having children is still you know is one answer to the question: do I think the human project should continue?

Greg Dalton: Have you talked to your dad about it?

Daniel Sherrell: I have talked to my dad about it and I know that my parents wanna be grandparents. And I think that's a very human instinct and one I'm deeply sympathetic to. But I think part of it is also their are sort of, not uncomplicated but less complicated position toward this question you know I think they have a hard time fully realizing, internalizing the climate crisis. I mean, I certainly do, and all their schemas were set in a world all their understanding is what the world is and how it works were sort of fixed in a period where global warming wasn’t anywhere on the map, you know. Exxon knew about it and was systematically suppressing it, but for lay people like my parents you know their formative years it wasn’t really on the horizon. So, I think it's hard and unsettling for them sometimes to see how much this rocks me like really rocks me in a way they can't quite access. But to their credit, they've come to respect that I think and give me space for that in a way that I'm deeply grateful for and that I, you know, I hope can become more common among boomers. Because other reactions I see more mainstream reactions was like oh, you’re overreacting you snowflake or like don’t be afraid like your generation is gonna solve it. And it’s like okay, thanks for passing the buck, bro.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, well, as a boomer I’m grateful for your book and your work. It really resonated with me as a climate professional and as a father struggling with some of these things. Daniel Sherrell is author of Warmth: Coming of Age at the End of Our World, a beautiful book. Daniel, thanks for your work and for your time.

Daniel Sherrell: Yeah, thanks so much, Greg. This is great.

Greg Dalton: The decision of whether or not to have biological children can be fraught for those concerned about our climate-disrupted present and future. Irene Mathieu [ee-wren MATT-chew] is a pediatrician and writer in Virginia.

Irene Mathieu: I have fallen on the side of having at least one child, I just gave birth to my first child three weeks ago, so I have a newborn at home right now. And it was definitely a year’s long decision.

Greg Dalton: Virginie Le Masson is a research fellow at the University College London focused on climate change and environmental degradation.

Virginie Le Masson: On my side it’s been two years of debating questioning and we still haven't made a formal decision as to whether having children.

Greg Dalton: And Seb Gould is a high school physics teacher, also in the UK.

Sebastian Gould: Me and my partner, we’ve debated for a very, very long time and we’ve come pretty solidly on the side of not having a child based on climate.

Greg Dalton: Climate One’s Ariana Brocious takes it from here.

Ariana Brocious: Irene, I was curious if you could explain your thinking about the climate disruption that we’re seeing and maybe how your thinking has changed a little bit and how you ended up arriving at the decision to conceive a child.

Irene Mathieu: Sure. So, I basically ever since I was a kid always imagined myself being a parent and it was something I just assumed that I would do at some point. And I started to have doubts or questions around that probably in my mid-20s as I became more aware of the climate crisis and then increasingly even more recently in the past couple of years, I’m currently doing a Master’s degree in public health. And I've gotten pretty involved in some activism and advocacy with a group of physicians who work on climate issues here locally. So, becoming more aware of these issues made the decision feel a little bit more tenuous for me and I spent a couple of years talking about this with my partner. And ultimately, what I decided was that there are two kind of big concerns in my mind. The first one was the ethical or sort of carbon footprint rationale for having a biological child, and whether or not I could justify that, and it seems like a selfish decision to have a child just because I wanted one. And then the other concern that I had of course was just the planet’s livability and my child's life in the future and whether or not they would have the kind of life I would want them to have. I think realistically when we look at what's happening with climate change it is very economically and geographically stratified and we see the effects of the climate crisis are not distributed equally in society. And so, for me personally, I think that I have the resources at this point to be able to provide my child with a life that I would hope that they would have. I think it's a false equivalency to say that humans must, you know, forestall things like as basic as having a child for climate change when we have large corporations and governments that refuse to regulate. And the real reason we have climate change is because of that, it's not because one person decides to have a child or two children or not.

Ariana Brocious: I wanted to ask Virginie if she can explain her thinking about it and how it is also changed because I think some of the things that you highlighted have factored into her decision as well.

Virginie Le Masson: Yes, absolutely I can relate to lot of Irene’s questioning and points. My doubts are very much related to the work that I do. And for the past 12 years I guess I read every day about the impacts of environmental degradation and the impacts that fall upon very diverse communities across the world. And so, obviously there is an argument that says because I’m privileged I live in the UK. I come from Europe I don't have to worry about accessing resources to protect my livelihood or to protect my families and my children are likely to be protected as well. But I find it really difficult to see myself in isolation from sort of the things that we witnessed elsewhere. We are all impacted by the levels of pollution of water of soils and air. And the severity of the consequences of that position for human health is dramatic and we know only a little of it because it's under-documented. And especially for children's development we only start to see the tip of the iceberg really and that's extremely concerning for me. I am very conscious with the moral responsibility of bringing a child to life and having to accept the risk that they will face themselves hardship in their lifetime. But this particular hardship of losing someone close, particularly a parent is one that I found really difficult to reconcile because I feel directly responsible for it. And it’s related to my work because I feel like the risk of me falling ill or my partner falling ill or my children falling ill because of environmental degradation is now rising exponentially. And that's how I find it really difficult to make a rational decision about conceiving a child given this awareness and knowledge that the environmental degradation we have created and that we are leaving to the next generations.

Ariana Brocious: Seb, you had said that some of the reasons you and your partner have thought maybe you won't have children, biological children, has to do with some of the inequities between men and women when it comes to child bearing, right or child rearing, really.

Sebastian Gould: So, that’s one of the issues actually that my partner leans quite heavily towards now. A lot of it is to do with the inequities just globally. So, we've quite recently comes to conclusion that it’s quite a privilege not to have a child and to be able to live a normal life. So, you know, across the world there are so many people who through lack of access so I mean if you look at the south in the US a lot of anti-abortion laws, economically it’s not very viable for a lot of countries. Having access to the health care,to the ability to not have a child is quite a privilege. So, that's one of the reasons why she is quite adamant on not having a child. But as well it’s to do with the fact that a lot of the responsibility with fall on to my partner. So, in the UK at least, I, as a man would have about 2 to 3 maybe four weeks with the paternity leave. And for my partner, it would be about three months full pay maternity leave. So, a lot of the responsibility would fall to her. We’re financially incentivized to have that sort of quite sexist idea of or should I say chauvinistic idea of raising a child where the man is the breadwinner and the woman stays at home. And we’re not quite a fan of that.

Greg Dalton: After the break we’ll continue this conversation about whether or not to have children in the climate crisis. This is Climate One. Coming up, children as a symbol of hope for the future:

Irene Mathieu: If 20 years from now, we have gotten off our addiction to fossil fuels and we have created new systems will I regret not having a child? Yes, I absolutely think that I would. (:10)

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. We’re talking with three people about their journey to decide whether or not to conceive a child amid the unfolding climate crisis. Irene Mathieu is a pediatrician who just had her first child. Virginie Le Masson is a climate researcher still debating the matter, and Seb Gould is a physics teacher who has mostly settled on not having biological children. Climate One’s Ariana Brocious spoke with them.

Ariana Brocious: So, I was gonna ask all of you what has been the discussion that you've had with your partner on this and have you been in agreement have you disagreed. Has it been a negotiation between the two of you to arrive at whatever point you've landed at with this decision?

Irene Mathieu: I can speak to that. So, my partner is definitely not as emotionally concerned about this as I am, and has been very much on the side of wanting to have children as long as I've known him. And we've had many conversations about this and basically, he sorts of fallen on the side of yes, it is a selfish decision to have a child. Human beings are fundamentally selfish and I don't think we can avoid that and if it weren't having children, there would be other selfish things we would be doing. And on the whole that life is more worth living than not, which I agree with on that point. And so, bringing a child into the world could be an important source of joy for both us and for that child. And we’ve both talked about how you know having a child could be also an opportunity to help make a difference if we can raise that child with an awareness of the climate crisis that we didn't have growing up. So, he's very much in favor. I think where we are still debating is the number of children. I feel that it's hard for me to justify more than replacement level fertility, so more than two children and he really wants three so we’ll continue to negotiate that.

Sebastian Gould: I think that’s a really fantastic idea honestly having that. Because I think a lot of people's main concern about the climate crisis and children is the idea of overpopulation, especially with countries in the West where the carbon impact of you know people living in America and the UK and Europe are so much higher than other people living all around the world. I think it’s quite interesting, Irene, that you said that it's you are aware that it was quite a selfish idea because that was one of the first things I said to my partner about having a child that it’s quite a selfish idea of thinking I want to have my child and I want to make its life better than mine as a sort of vanity project. And it’s something that my partner never even thought about because she just grew up with the idea of oh that's just what you do. I think I've mellowed out a lot more so I don’t think the idea of having a child is as inherently selfish. I think I’ve got a lot of selfish reasons as well why I don’t want to have a child.

Ariana Brocious: In this episode we’re also talking with author Daniel Sherrell and he's written a book somewhat addressed to a future child of his that he writes, “I realized if I was ever going to start a family. If I was going to bring you into the collapsing world at hand. I’d owe you an honest account of why.” So, I'm wondering if for those of you who are thinking of having children or have, if that’s something you thought about that you would sort of need to explain to them your decision to have them?

Virginie Le Masson: That's part of the issue for me is I don’t know yet what I would say especially if they suffer for all sorts of reasons. How do I face myself if they ever blame me for coming to life and haven't had a choice? And a lot of people argue that it's a gift to be brought to life and we should be grateful for it. But it has, there could be so much suffering, for which we can try and compensate for it especially if we have privileges. But we can't control everything and so, the question and the dilemma I’m facing is that do I accept on behalf of another person to take the risk for them. And I know I would dedicate all my energy and heart to help them as a responsible parent but yeah, I can’t control everything. And this is why it’s so difficult to make a rational decision. On the emotional side I know I want to have children I always wanted but on the rational side, I don't know. And I've kind of had the same sort of a dilemma before that Irene raised and also Seb about, you know, the responsibility, the carbon footprint of children. Some people said, I was the best climate advocate because I didn't children and some people say why you’re so selfish not to want to have children how can you deny your parents to become grandparents. There are all these social sorts of injunctions on this especially on women, which I came to terms with and I don’t really feel pressured or...It's rather actually, this I'm blaming my partner because he’s brought this literature that I wasn't aware of from his philosophy teacher who wrote this piece asking is it moral to have children. And this brought to me so many questions I never considered before including the first one I’m battling with is how do I tell my children if they are unhappy if they’re suffering that I made a conscious choice to bring them up to life because I wanted to have them. Is this valid, is this good enough? I still don't know.

Ariana Brocious: So, you've raised this really important question about this sort of rational versus emotional part of this decision. And so, and how you can struggle when those don't actually meet up. Have the other two of you struggled with that part of it?

Irene Mathieu: Absolutely. I actually spent much of my pregnancy writing a long essay about this very issue. That rationally, I think for me anyways, it is very clear that having children is probably not a great idea, but I think the larger maybe the larger force for me in making this decision is intuitive and not rational. And I had a conversation with a friend before I got pregnant and I was sort of outlining these thoughts to her and she is somebody who's decided not to have children, although not for climate reasons for other reasons. And she said, you know, maybe this is not there is no answer right answer to this ethical debate. But maybe just your certainty and your deep feeling that you are meant to mother in this way is enough to answer the question and then it's about how you do it. There are people who choose not to have children and people who choose to have children. And I think all of us are important in the climate crisis and all the other crises facing the world. But, you know, one thing that was helpful for me in coming to this decision was thinking about all of the populations of people who have gone through crises that felt world-ending in a way. I think about my ancestors who may have been enslaved and certainly not every reproductive choice in that system was really a choice. But there are people who have chosen who continue to choose to have children under really, really catastrophic conditions and it's a symbol of hope. And so, I think for me really following my intuition for a choice this big made more sense than trying to settle a rational or ethical debate because I think that it's kind of an impossible question.

Sebastian Gould: Yeah, the idea of the rational versus the irrational part of your brain almost like the lizard part of your brain that wants to reproduce like that's the whole reason why we’re here because humans keep on reproducing and we do it well. So, it’s sort of fighting that instinct really and, yeah, I mean I’d say for myself and even my partner I think just yesterday she just said, I love the idea of getting pregnant. But then for her at least it’s thinking about oh but then it’s all the other stuff that comes with having a child. And I think when I think about that quote that you gave from the author, I don’t think I could ever justify to a standard that I’d be happy with to any future children that I would have had a reason to bring them into this world. I don’t think I could reasonably justify that and I think that’s really the crux of the issue. If I don't feel that I can do that then I just simply won’t.

Virginie Le Masson: From my perspective I change every day. One day I feel like I'm ready and the next I’m like never, no way. And it has been the case for two years now and up to the point when we decided to set ourselves a deadline because there’s also the time issue that for me is the biggest problem actually. And actually, I think we are blessed in this generation that people are very cautious not to put too much pressure to us. And we are surrounded by very diverse relationships with people who decide not to have children with same sex couples or. And it's wonderful to see that no matter what we’re gonna be fine and people will respect our decisions. And I know it's not the case in many other societies. But that also means that it changes our own decision making process. There was a time a year and a half where actually we thought we were not gonna have children at all. And now I think it’s not so certain. And to allow ourselves to be hesitant and to be transparent was really helpful at least for me because it's okay to change our minds as well.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, and I want to jump in here because this is you know, as evidenced by our discussion. This is a really fraught and difficult decision for a lot of people. It's emotional, it's heavy. But there are some 3 million children born every year just in the US alone and I would be willing to bet a lot of those parents for whatever reason are not thinking about these issues, at least to the degree that you all have. So, Irene you've touched on this already but I mean, how much do you think your decision your personal decision in this matter in the larger scheme of things?

Irene Mathieu: Honestly probably not much. I think it matters mostly for assuaging my own personal sense of guilt or goodness in the world. I don't think that the carbon impact of one or two children is going to change the tide of the climate crisis even children in a high-income society like the US. And so, I don't really think that my decision matters that much in the larger scheme and I think one of my bigger concerns that I alluded to at the beginning about this whole question is the idea of the carbon footprint which was created by British Petroleum to put the onus back on individuals and say we need to watch how much toilet paper we use and how many miles we drive because it's our fault instead of taking responsibility for really contributing to the climate change as big industries. And so, I'm more interested I think at this point in shifting my energy and my focus to bigger policy issues rather than my own individual decisions, which are really kind of small fish when it comes to the actual impact.

Sebastian Gould: I don't want to sound pessimistic or anything, but what about living in a world where we can't change, you know, how big companies pollute the ocean and surely the best decision we can make then, is to not have to, you know, reproduce people who use these big businesses’ services. That for me is one of the things that I feel quite passionately about is yes, we should be advocating for better policies you know in government to regulate these huge corporations. To tax them appropriately and to regulate them but at the end of the day, chances are that that’s just gonna carry on. I mean I don't wanna sound pessimistic but for me that decision is I've made the choice to not have someone else need to use this stuff. For me, that’s another part of my reasoning there and I don’t know how you feel about that.

Irene Mathieu: I guess part of me thinks we can’t predict the future, and while I would also say my nature is probably to be a little more pessimistic as well. If 20 years from now, we have gotten off our addiction to fossil fuels and we have created new systems will I regret not having a child? Yes, I absolutely think that I would. And so, that plays a big role in my thinking, but also, I think part of the responsibility that I've now accepted in having a child is trying to divest as much as possible from those systems. And I know that I can’t do it a hundred percent but you know I live within walking distance of our local elementary school and several grocery stores. We’ve discussed getting investing in solar power so our home can be solar powered. And those are certainly very privileged decisions, at least in the US not everyone can make those decisions. But I think that if I'm going to have a child in a society like this one that is part of my responsibility. Becoming pescatarian is something once I finish breast-feeding and can sort of afford to do that calorically trying to really reduce our meat intake. So, things like that I think are absolutely part of our responsibilities. So, my child learns how to live in a way that is minimizing that resource usage.

Virginie Le Masson: Perhaps I can bring a middle ground there. Part of the reason why my thinking changes so much it’s also because in the last two years we've witnessed Fridays For Future and the rise of the youth movement for climate change. That’s been fantastic to witness and to support and to see all these young people so much more informed than we ever were at their age. So many young girls, you know, taking to the streets to protest for things that they care about and that they can and they’re not scared to protest. This is bringing me a lot of hope, which has also changed my perspective and slightly shifted the attention on my responsibility to actually trusting the future generation because at some point, people would try to reassure me saying because you care then your children will care but then I felt it’s unfair on them because it's put the responsibility on them rather try to think more collectively that I trust the next generation to care more. And we cannot change at the moment what’s going on at the highest level and believe me this is part of my job trying to influence policy decisions being done at the UNFCCC negotiations for example. It’s so slow and so yes slow that I don't have any hope within that process. Rather I feel like this more localized or perspective to think about my own community and having this conversation about procreation actually is changing little things at the local level. It brought me joy and hope actually much more than any other aspect of climate activism so far.

Ariana Brocious: Virginie, I had a question for you because at the beginning of this conversation you have been the person who’s still undecided. What if anything that either Seb or Irene has said resonated with you and has maybe given you something new or different to think about or will continue to sort of I don’t know be part of your thinking on this as you go forward.

Virginie Le Masson: I completely agree with Seb’s pessimism. I feel the same way this sort of feeling of frustration and yeah, and it’s really draining and it's not a happy place and also completely share his partner’s thinking around the imposition of society's norms on reproductive roles for example. And if I knew that my partner had equal paternity leave that would really change my decision, I think. And on the other hand, giving Irene just having a baby just brings me so much hope. I feel like actually this resonates with my guts and that it goes to this emotional feeling that this is probably what I want and that’s what I’m gonna try probably to go to. Because my partner is so indecisive that I felt it’s almost down to me to really decide. And it’s also related to this question of rights and reproductive rights. And a woman, I feel like I’m in control of my contraception and part of it is quite a big responsibility. So, hearing someone who’s came over this doubt and this dilemma with some really good reasons, it gives me a lot of hope.

Ariana Brocious: Well, thank you all so much for taking the time to talk about this really difficult subject frankly. And thanks for joining us here on Climate One.

Irene Mathieu: Thanks for having us.

Sebastian Gould: Thank you very much.

Virginie Le Masson: Thank you.

Greg Dalton: On this Climate One... We’ve been talking about the difficult decision of whether or not to have children in the climate crisis. Here’s a note about the big picture before we end. Global fertility rates are falling. In the United States, the birth rate has been declining for several years and in 2019 - before covid - hit the lowest rate in 32 years. A 2018 New York Times poll on the issue cited top reasons as the high cost of child care, desire for leisure time and financial uncertainty. A third of young adults identified climate change among reasons for having fewer than their ideal number of kids. The issues are complicated, but Irene, Seb and Virginie have a lot of company. Special thanks to Stanford researcher Britt Wray for her help with this week’s episode. Find a link to her thoughtful blog about parenting and climate in the show notes on our website.

Greg Dalton: To hear more Climate One conversations, subscribe to our podcast on Apple, Spotify or wherever you get your pods. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. It really does help advance the climate conversation.

Greg Dalton: Brad Marshland is our senior producer; Ariana Brocious is our producer and audio editor. Our audio engineer is Arnav Gupta. Our team also includes Steve Fox, Kelli Pennington, and Tyler Reed. Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.