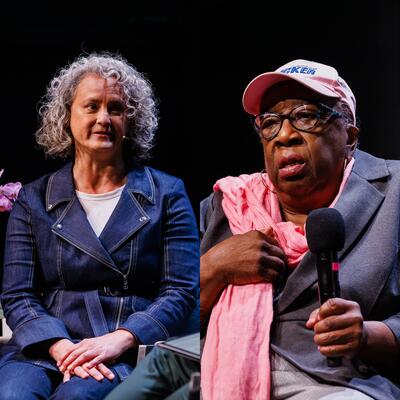

Power Shift: Jamie Margolin and Dorceta Taylor

Guests

Jamie Margolin

Dorceta Taylor

Summary

How does power shape our climate and our future? For young activists, speaking climate truth to power can be daunting when climate change is here and now and your future seems in doubt.

“No little girl is like dreaming and she's like, I hope to spend the rest of my life desperately fighting against this massive catastrophe,” says Jamie Margolin, co-founder of the youth climate justice organization Zero Hour.

At age 18, Margolin is also author of Youth to Power: Your Voice and How to Use It – though she’s under no illusion about the kinds power young people can actually wield.

“A lot of young people can’t vote yet ... they don't hold the political power in terms of office and don’t hold all these other things,” she says. “The power that we do have is to shift the needle towards change by shifting the culture, because culture shifts cause shifts in law.”

As we think about a shift of U.S. presidential power, how can we expect those who do wield power to confront the twin crises of covid and climate?

“It is precisely for people when they vote to not just think of the vote as voting for health or voting for schools or libraries, but to start connecting the dots,” says Dorceta Taylor, Professor of Environmental Justice at the Yale School for the Environment. “That's another dimension of power.”

An original leader of the environmental justice movement, Taylor sees support for strong racially inclusive climate action garnering power, as evidenced by this year’s street demonstrations, school strikes, and the first-ever question about environmental justice during a presidential debate

“Once you can start connecting large things that look unrelated, then you really have taken a very first step in liberating yourself, educating yourself, but making a very informed decision that would make it very clear how you should vote in this upcoming election.”

Related links:

The Rise of the American Conservation Movement: Power, Privilege, and Environmental Protection (Duke University Press)

Toxic Communities: Environmental Racism, Industrial Pollution, and Residential Mobility (NYU Press)

Yale School for the Environment

Youth to Power: Your Voice and How to Use It (Hachette)

Zero Hour

This program was recorded via video on October 26, 2020 and September 15, 2020.

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. Talking climate truth to power is no small undertaking.

Jamie Margolin: No little girl is like dreaming and she's like, I hope to spend the rest of my life desperately fighting against this massive catastrophe.

Greg Dalton: Fighting for environmental justice can be overwhelming when climate change is here and now, and putting your future in doubt.

Jamie Margolin: You have your moment where you’re like literally the world is trash and nothing means anything, but then all you can do is continue to act.

Greg Dalton: As we think about a transfer of U.S. presidential power, how will our leaders confront the twin crises of covid and climate?

Dorceta Taylor: It is precisely for people when they vote, to not just think of the vote as voting for health or voting for schools or libraries, but to start connecting the dots. That's another dimension of power.

Greg Dalton: Climate, Justice, and Power. Up next on Climate One.

---

Greg Dalton: How does power shape our climate and our future? Climate One conversations feature all dimensions of the climate emergency, the personal and the systemic, the exciting and the scary. I’m Greg Dalton.

Jamie Margolin: The power that we do have is to shift the needle towards change by shifting the culture. Because culture shifts cause shifts in law.

Greg Dalton: Jamie Margolin is Co-Founder and Co-Executive Director of the youth climate justice organization Zero Hour. At age eighteen she’s also the author of Youth to Power: Your Voice and How to Use It. She’ll join us later to explain how she’s helped build a climate youth movement, from first-time activists to families on the frontlines of pollution -- a subject that came up in the most recent Presidential debate.

Potus: The families that we’re talking about are employed heavily, and they’re making a lot of money, more money than they’ve ever made.

Dorceta Taylor: When you look at those jobs, they’re short-term, they’re low wage, they are not jobs that help people in the long haul.

Greg Dalton: That’s Dorceta Taylor, Professor of Environmental Justice at the Yale School for the Environment, and an original leader of the environmental justice movement. I began our conversation by asking Dr. Taylor for her reaction to a definition of power cited by Dr. Martin Luther King in March of 1968. Speaking in Memphis to striking sanitation workers, he said QUOTE We can all get more together than we can apart, we can get more organized together, than we can apart. This is the way to gain power, power is the ability to achieve purpose. Power is the ability to affect change. We need power.”

Dorceta Taylor: I think it's very prescient, and it's still very a propos about what's going on, because power really is not only the ability to do things, but it's also the ability to get others to do what you want them to do. And it's the ability of groups of people to consolidate and extend, actually elevate their ability to get their desires accomplished, and we are seeing that in the US, at an unprecedented level, were very small numbers of people are able to put forward narratives, but also to execute plans to get outcomes that they desire to benefit themselves and those that they value, but also to disenfranchise authors who are not in the in-group with them. Today with traditional ways of organizing and doing and mobilizing in addition to technology to media to kind of understand global inter-connections, we're able to do it on massive scales with very different amounts of resources, so with power comes that understanding of how one can manipulate various things to get that outcome, even if one's poor or one’s not in the traditional class of power brokers.

Greg Dalton: Right, and supporters of strong racially inclusive climate action have garnered power this year as evidenced by their presence in the street, the school strikes, and the first ever question about environmental justice during a presidential debate. Debate moderator Kristen well, car as President Trump why people in Texas living near oil refineries and chemical plants should give him another four years when he's eliminated Environmental Protections that regulate those types of facilities. What did you think when you heard or read about that question?

Dorceta Taylor: You know, a response to that is it is precisely for people when they vote, to not just think of the vote as un-voting for health or in voting for schools or libraries, but to start connecting the dots, that's another dimension of power in how we understand how things that might seem completely disparate, do I live beside a coal-fired plant or not, or do I... Lieder is indeed related to how many covid cases are in your community, how the healthcare system operates, what kind of hospitals you have, what kind of schools, illnesses in school, your children perform, and it's on the electorate, regardless of education, regardless of cultural background, once you can start connecting large things that look unrelated, then you really have taken a very first step in liberating yourself, educating yourself, but making a very informed decision that would make it very clear how you should vote in this upcoming election.

Greg Dalton: And isn't it true that people of color actually pull higher when it comes to climate concern and change, partly because of the reasons you just said that they're often closer to the impacts...

Dorceta Taylor: Indeed, not only do they pull higher studies that have been conducted since the early 1990s, again, at the beginning of the formalizing of the environmental justice movement, the League of Conservation Voters have tracked how people are voting, and they've tracked the Senate and the House and black congressional representatives, vote more systematically pro-environment, support environmental legislation than any other group in Congress, and that's something that doesn't often pop out, but that kind of pro-environmental voting record has transition or is translated into the communities that they represent wanting these things. So it's not just League of Conservation Voters. If we look at Gallup polls that go back quite distance, decades, we see African-Americans, Latinx communities are more likely to say they will support government spending for environmental improvements than other groups in the society, and so what we're seeing with the youth around climate and the interest in climate and the activism that's going on on the crown around across the country is coming out of that background of communities that are willing to pay for and opt for options that will improve our chances in terms of dealing with negative climate impacts.

Greg Dalton: There's another current going the other direction though, which is fossil fuel companies have cozied up to the NAACP and other organizations to try to get black and Latinx communities to come on board for some of their plans, power plants, etcetera, that aren't necessarily in the interest of the members of those organizations, so speak to the other side about how some powerful fossil fuel interests have tried to work their way into those communities of color and some of the top tier institutions

Dorceta Taylor: Yes, good question. And that piece of it has always been a part of the divide and conquer strategy, so if you go back again to the 1980s, 1990s, corporations, for instance, when they wanted to site their polluting facilities in the south, they would come in with the promise of jobs. So they take the economic argument, and when you look at those jobs, their short-term, their low wage, they are not jobs that to help people in the long haul, so that's been a long-term strategy to try to get some communities of color to host these facilities or to get organizations led by people of color to endorse what's going on. They have never made extremely large inroads into the wider community, because if you look at again, if you look at climate, if you look at broader environmental justice for everyone or so group that they might get to endorse or to collaborate, you have a large number of other groups completely opposing or not wanting to be a part of the corporate, necessarily corporate response, that being said, you do have to think through what are the ways in which we move forward to get better environmental outcomes, if that's the long game is, if that's the long-term goal, then one has to see how that happens, how does one hold corporations responsible for harms, but also help them to see how they can shift and help the communities that are being affected to see how they can actually improve environment, community living, but overall standards.

10:27 S1: The American story is largely about land and Manifest Destiny, and in this election, one side presents a story of glorious American exceptionalism and white dominance and other side is reckoning with an American story that's fraught with actions that are hard for white people to confront the stealing of land from indigenous Americans and enslaving blacks and keeping out Asians. What does that story from your perspective, and what do we not learn in school that we should have...

Dorceta Taylor: Yes, in school, I think many people missed or the discussion just didn't occur around how do we still all benefit, but acknowledge difficult chapters in history that occurred, difficult decisions in moral decisions, decisions that were patently incorrect. How do we acknowledge those and think about our society today, and think about how do we move forward and make some of those home? So when we have a country in which some people were deliberately seen as objects as just tools to get agriculture completed, to clear the land, people that have no rights simply because of their skin color, other people whose lands were just... Someone just looked at it and decide, I want that, I'm gonna take it. You will not have it. How do we today, with the hindsight of history, but with, I think in some ways, a more sophisticated understanding of how we should engage as human beings, how do we move forward and have that respect for each other, have that understanding that somebody's skin color shouldn't be so fearful that they're killed simply because of how they look, not because of what they think, not because of what they can contribute to the society, but simply based on how they look, how are we gonna in the long haul, succeed as a society, if we continue what we're continuing now. Who’s to say we're not killing off the next person who could invent the very thing that could save us all when we run out of resources, what are we gonna do in this country when in about another 25 or 30 years, we become a country where there are more people of color in the country than white, what are we gonna do, and how are we preparing ourselves to reconcile that and get the best out of each other, not the worst, not elevate the people who are willing to play to the worst, but to go through the uncomfortable spaces that we need to traverse to be able to understand and move in a way that we all benefit later on hen we need clean water, fresh air, enough food as a globe for us to all survive.

---

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation about climate and justice in 2020. Coming up, finding inspiration in history for environmental justice today.

Dorceta Taylor: Harriet Tubman -- I was reading a bedtime story to my twin daughters when they were about three years old. I felt I just stopped in my tracks, and I said, she's an environmentalist, she's one of the earliest environmentalists.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

---

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton, and we’re talking about climate, justice, and shifting powers with Dorceta Taylor, Professor of Environmental Justice, Yale School for the Environment. In addition to focusing on diversity, equity, inclusion in the environmental movement, Dr. Taylor spends a lot of time teaching students — who she says are growing up in a world that’s very different from their parents’.

Dorceta Taylor: Something like the National Parks. It was a brilliant idea to think about, as a country, do we have these most amazing spaces that when you go to... I've taken students to Yellowstone and they stand... Groups of students that are very multicultural students, most are coming from inner city neighborhoods, they just happen to be really incredibly smart students that nobody or a lot of people don't give an opportunity to in the environmental field. I do in my program, take them that to Yellowstone and we use your coming in on a trail, and if you are going to the rim of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, the canyon is behind you as you approach it, and the waterfall is behind you, and you're looking down into a very spectacular part of the canyon, but it's when you turn around and they're usually talking 'cause they're 20-something years old and they're on their phones that are not working, and I often point and say to them, Look behind you, and when they see it, that look of awe under faces and the look of awe on everybody's faces, but that being said, we cannot go there and experience that awe without recognizing that this was an another people's homeland and that homeland was taken without adequate compensation, taken period to create the space that we can now since 1872 go in and enjoy, the idea of not turning them over unfettered commercialism, that was something that was brilliant that people saw early on that if they weren't protections around them, they would be put into private hands. That was another piece of it. These should never be in private hands to own them, it should be for the people to enjoy... But the idea that we don't want to fully own that these are native homelands, and that we should reconcile how we go forward with this, how we think about compensation, how we think about who runs it, whose ideas should be reflected in it when you go to spaces, like the Grand Teton, you'll stand at headquarters on the plaque that literally has these pointers that to every peak, and it tells you the name of the first white male, and I think a couple have white females that went to these peaks, and I remember just standing there getting really very annoyed at the fact that are we suggesting that a native person didn't bring those visitors in and help them to get to those peaks or that we're supposed to see him that... These peaks are sitting there, you’re tribal member, and you have had no curiosity for so many centuries to go up there and see what's there, it took a European to go there?

Greg Dalton: You said you temperament, you start to tell... Or you said you were annoyed as someone who's studying the history for decades, as you have... Do you ever get really angry, you have such a calm, soothing voice, I wonder if you ever get enraged when you're looking at those plaques at Yellowstone, the Tetons, you ever get just really mad?

Dorceta Taylor: It's a good question you ask 'cause I've had people... I had a young African-American scholar who was doing some writing, and she called me up and she asked the same question, she says How... And students have asked me how do you do this research, especially for something like The Rise of the American Conservation Movement: Power, Privilege and Environmental Protection. Do you not get very angry because your books don't sound angry or when I express it to you... And I said to her, I know how to pace myself. Now, and it is a part of... First of all, incredulity, when you first read and see something, and then second, dismay. And then third, how can I do something to change it? And yes, that anger or resentment is there, but I could get a heart attack if I get angry every time I encounter one of this. And another question folks often ask me is, How did it ever occur to you to think, for instance, of talking about someone like Harriet Tubman as an environmentalist, or Phyllis Wheatley as being of a person who started to write in environmental thinking and ways before Henry David Thoreau, before Ralph Waldo Emerson. And it's keeping that calmer demeanor and that calmer way of thinking about this, that my mind takes me into places where I can connect these thoughts, and sometimes I ask myself or wonder, Are you crazy Dorceta, what makes you think that actually works? But it helps me to do that. Harriet Tubman, I was reading a bedtime story to my twin daughters when they were about three years old, yes, these are the crazy things that academics read to their children, the story of the Underground Railroad, that I was reading the children's version of it to them. As I was reading it, I felt... I just stopped in my truck, like says She's an environmentalist, she's one of the earliest environmentalist for her to have been able to... As a woman, to do it on her own, beyond phenomenal, but as I was reading this book, my mind wanders off and luckily my daughters had drifted off to sleep, and they thought for her to have been able to successfully escape the first time on her own, but do it repeatedly, and freed more slaves and almost anyone else required an incredible amount of environmental knowledge, we can celebrate John Muir, Thoreau, and what they did and their hikes of all that are important, but here's a woman that hiked more than they did, she did it at night, she did it with dogs chasing her, she did it with the highest bounty for any slave ever on her head, and she was able to successfully do it, so it's the ability to still have this annoyance as I called it, to be able to move past that, to then be able to connect something like a Harriet Tubman life story into the environmental narrative that when young black kids read that and when I give talks where I talk about that, I've had black people that really jump over chairs and benches to say, I've never ever seen myself an environment, you've just made it clear to me why I must care about the environment, how my life is connected to it, how some of the things I've seen my family do and I didn't quite understand how it's a piece of the story and how it's revolutionized how they think.

Greg Dalton: If Joe Biden wins the election, environmental justice advocates are urging him to appoint an indigenous person to lead the US Department of the Interior, which includes the Bureau of Land Management and the National Park Service. We've been talking about overall Department of Interior provides over about 12% of the American landmass and billions of dollars in oil and gas leases. It’s a massive agency that many coastal and urban people don't know much about. What would be the significance historically of an indigenous person leading the U.S. Department of Interior?

Dorceta Taylor: It would be phenomenal in the sense of if we think of where does the Bureau of Indian Affairs sit. It sits in that same agency that's a part of the Department of Interior. Part of the control of native people at one point was to put Indian Affairs under the War Department. And so, to have a native person, an indigenous person, first of all, be in control of that much physical land in the U.S. that in of itself is just historic. But to be in a position of authority and decision-making over those resources, many of the oil and gas leases many of the wind resources many of those things are on tribal lands. And so, the idea that if we’re gonna talk about diversity if we’re gonna talk about inclusion. If we’re gonna talk about antiracism if we’re gonna talk about creating a new way forward in the country. We cannot be afraid of looking at who are the people who have stewarded this land and why haven't we had a native person in a position like that before.

Greg Dalton: My guest today is Dorceta Taylor, professor of environmental justice at the Yale School of the Environment and an original leader of the environmental justice movement. Dr. Taylor, New Jersey recently passed a law that has been called by some the Holy Grail of environmental justice. It requires the rejection of new power plants, incinerators, landfills, large recycling facilities and sewage treatment plants in certain minority and impoverished neighborhoods if the projects present health and environmental risks in addition to the burden those communities are already carrying. What’s the significance of that New Jersey new law?

Dorceta Taylor: Well what that is really trying to recognize is the idea of disproportionate impacts. So if you have a community that is a host to maybe say a mining facility. Do we then think that that community also should have all the waste dumps. When we want to have industrial facilities, mining, commercial facilities, why do we think that just one group of people or one set of communities should be the host for those? And so, the idea of disproportionate impacts really gets at the idea of when you take all these negative things and you start multiplying them and place it on one community, one group that is something that we really ought to take seriously and start looking at what are the overall impacts. What does that mean from a perspective of health of the community longevity. How long are those people gonna live? Are we really being very efficient when we are sacrificing people because we know their lifespan is going to be shortened. What's gonna happen in the schools does it cost us more to then be able to educate all the kids that are gonna be in special ed and who will be needing all the extra resources that those things by concentrating so many negative things in one place. Who’s going to pay for the hospital?

Greg Dalton: In your 2014 book, Toxic Communities, you looked at the question, why don't people just move away from places like St. Charles, Cancer Alley in Louisiana or elsewhere?

Dorceta Taylor: Yes, because that's a question I would get. I still get them, but I used to get that question a lot if you do a seminar or you give a talk. And even in the classroom, even teaching students and these are not reactionary students. These are students trying to grapple with that simple question. Why don’t they just move? And so I almost titled the book that was almost the title of the book, and it’s usually they just move. And even from students of color would ask that question. And it isn’t always as simple as that because if you live in a community or an area where because of your race, you are prohibited from living in certain neighborhoods, your family might not just be able to move. With students, one of the exercises I’d have them do when that question comes up is to process the map out what are the costs of moving. People also assume when they say why don't they just move that the low income or the people of color are moving to the facility after it's been built. They're not asking the question did the facility come to the neighborhood after people were already there. Can you afford to buy because if you own a property also, in some of those neighborhoods your property values have dropped some time to the point where you will not recoup your cost if you have to sell the house to then be able to pay off the mortgage. This shock a lot of students that if you have a property and it's beside one of these facilities and it's completely the property value has been lost. If you get see a government payout or a corporation pays you for the property, they don’t realize you have to pay off the mortgage on it first before you can do anything. Because they just thought you just pack up and move.

Greg Dalton: Right. We’ve certainly seen during COVID that knowledge workers have a lot of privilege to move out of place or because of fires and people who can't move – so there’s lot of privilege built into that question. The United States is undergoing a generational transition. Millennials have passed baby boomers as the largest living adult generation. And Joe Biden says he will be a transitional president if he wins. What advice do you have to young people concerned about the climate, we’re talking later here with Jamie Margolin, a teenage climate activist. What advice do you have her and others in her generation to write a new American story on race, power, and the environment?

Dorceta Taylor: I see the young people and I for a long time had just incredible hope and incredible admiration for the millennial generation. One of the things that they have brought to the table in a very powerful way, is they’re not afraid or they're not as afraid of racial mixing as their grandparents were or as their parents were. They have grown up going to school together with people from different cultures, backgrounds, classes. They've gone to college where they had to share rooms and dorms. I take people on a field trip and I remember being on a field trip with some students and I thought if your conservative parents from another part of the country could see you now because there are three or four kids in a room where there are different colors of them on the bed. And I remember saying, whose clothes do you have on today? I know that’s not yours. And they’re sharing out their clothes even their undergarments. And one of the things when I was at Michigan, Michigan deliberately created a set of options for students. So, these are not study abroad options. These are these multicultural shorter-term trips that a professor takes the students and we all live together and they did it for exactly that reason. That if you're all miserable and the mosquitoes are biting you and you are all having an experience together you break down some of this stuff and all of a sudden you start to see the commonalities and you see the different skill sets. So, the millennials bring that piece to the table that they are very much more wanting to understand how to live multiculturally. You saw in the protests, kids from every color, every stripe being tear-gassed by the police not running home to the suburbs and being defiant and being a part of that the fierceness of this generation is that’s part of their secret weapon. And they also have lived in homes so they have had to argue some of these cases. A lot of my students say to me, when I go home, I have family members that say some of the most incredibly racist things and I have to know how to hone my arguments to speak with them so I don't get thrown out of the house. And so, at home they’re fighting some of these battles.

Greg Dalton: Well Dr. Taylor, Taylor, thanks for coming on Climate One and sharing your insights on privilege, power and the environment. It's been a pleasure to talk with you.

Dorceta Taylor: Thank you for having me. It's been wonderful.

---

Greg Dalton: You're listening to a conversation about climate and justice in 2020. This is Climate One. Coming up, how today’s youth activists balance fighting for their futures while living their best lives now.

Jamie Margolin: I'm just trying to find joy where I can while the world is in decline, which is a very scary and unsettling thing to do while trying to plan and study for a future that you're not even sure even exists.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

---

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. Jamie Margolin is Co-Founder and Co-Executive Director of the youth climate justice organization Zero Hour. At age eighteen she’s also the author Youth to Power: Your Voice and How to Use It. A native of the Pacific Northwest, Jamie writes about defending the mountains of her homeland as the primary motivation for her climate activism. I began our conversation by asking how she felt during the fires that are ravaging the American West.

Jamie Margolin: I am currently at New York University studying film and television. So, I am in New York watching the fires happen from afar and it's very surreal seeing pictures of my hometown and my parents sending me pictures of the sky. It was ironic when my best friends were sketching the fury and send me a picture of a sign and like everything was smoky and a sign that says no smoking or vaping. That was kind of ironic because breathing the air is like smoking a pack of cigarettes right now or more. I don't know the exact statistic. But it was just seen these images are surreal because back in 2017 the smoke from the wildfires blew over Seattle and coated a small layer of smog, but it wasn't as bad as it is now. And I could never imagine it getting any worse but it did. And back then those initial fires and that initial smog is what propelled me to start Zero Hour the youth climate justice organization. And now like three years later and it's only gotten worse and it's very frustrating because I’ve been doing this work for so long and yet this is the result. This is what's happening it’s still getting worse. Leaders still haven't taken action. I’ve been fighting for climate justice for almost five years now and it’s still nothing but just worsening of this crisis.

Greg Dalton: And you’re going to college during this time you’re going to NYU. I read that there’s a one of the dorms at NYU is now under quarantine. So that seems like a lot to carry for someone like you at this time to watch your home burn while you're in college and there's a COVID quarantine.

Jamie Margolin: It's a very difficult situation in many ways because of the uncertainty of everything like it's hard for me to like settle into my life in college because I don't know if there will be an outbreak at my dorm. Like right now my dorm is fine, but they’re testing us weekly and so results are coming in like every week, every week, every week. And I’m just scared like what if there are so many positive cases that we get sent home and I have to scramble to find a way to stay in New York because my goal is to stay here stay in the city. But if I don’t have college housing then like I’m gonna have to scramble and it’s gonna be difficult. I don't know like I'm really nervous. That's why people are like when I FaceTime my friends, they’re like your dorm is so bare and boring. It's just like wait, where are your signs where are your posters? I’m like I don't know if I’m gonna be sent home tomorrow. So, I'm just like living very tentatively, uncertainly and there’s this just anxiety there's no certainty. So I’m just trying to make the most of each day but it's difficult to make the most of each day when you have like three essays due. So, you’re like I’m gonna make the most of the time I have but then you look at your homework load and your emails and it’s like it’s striking a balance between getting your work done and trying to make the most of it of life. I mean people act like 2020 is some strange curse, but honestly all of this is because of long-term issues. So, I don't know if it's gonna get worse so I'm just trying to like find joy where I can while the world is in decline, which is a very scary and unsettling thing to do while trying to plan and study for a future that you're not even sure even exists. And I haven’t been able to like exhale and settle in because I don't know if there's anything to settle into.

Greg Dalton: Right. And even calmly breathing these days or breathing deeply can be dangerous these days. You write about not losing yourself in your cause and say remember to care for yourself and sibling, lover, whatever. How do you do all that while also the things you mentioned, but also a growing public profile. You’re 18 you published a book, you’re talking on radio shows, you’re on social media. How do you juggle all that?

Jamie Margolin: I think a lot of it is trying to focus on what brings me joy. I mean a lot of people expected me to go into politics which is why a lot of people were surprised when I made my announcement like I'm going to Tisch to study film and television. And people were like, what why she doing that? And they’re like, oh it’s because you’re gonna make climate documentaries, right? And I'm like nope I want to do nothing that has anything to do with climate change. Because what I want to do what I've always wanted -- no little girl is like dreaming and she's like, I hope to spend the rest of my life desperately fighting against this massive catastrophe. That’s not what I dreamt of when I was little. And I will be fighting because survival is an instinct and I will always be fighting for the survival of our planet. But in terms of my career for my own sanity for my own happiness I need to have something in my life that I'm working towards that has absolutely nothing to do with this crisis and absolutely nothing to do with the climate catastrophe. And so I'm a storyteller and I really love to write screenplays and tell stories and direct and make things come to life and I love movies and I love shows and I've such a passion for arts and theater and creativity and acting and I really want to bring all these things together and make beautiful narrative cinema and TV shows that have nothing to do with the climate crisis. Not because I don't care, but because I need just one aspect of my life that isn't taken over by this crisis.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, that’s very wise because it can be all-consuming. I’ve been in this for going on 15 years and seen a lot of people be consumed by it. And you write that you’re propelled by outraged. Does that outrage ever, how do you keep that outrage in check because some activists get really angry and bitter and ineffective.

Jamie Margolin: My outrage kind of manifest into a general baseline of cynicism and negativity. Like I'm not punching walls, but I am like how many more not a desensitization but more of like a normalization of everything being up in flames. Not just like literally with the West Coast being on fire, but also just like with the climate crisis. If you live and breathe bad news and eventually it’s gonna like wear you down. And I don't really feel like I am angry but I’m not like punching drywall I’m more of just like like the other day when the fires like when it was like hey guys, the entire West Coast is on fire. I couldn't finish my homework. I couldn't do anything like I was just completely frozen with terror and fear. I just called up a mentor of mine and I was like little enough thing means anything. Like with the COVID crisis and us being on the edge of fascism with the current administration and the climate crisis. It all just feels too much. I'm tired I can't do this. But then I just said that I'm just like, oh my god I hate this I can’t do this and then I just get up the next day and do it anyway. It’s more of just like you have your moment where you like call someone and you’re like literally the world is trash and nothing means anything, but then all you can do is like continue to act. So, my life I mean, I had that exact moment three years ago where I was like literally nothing means anything, this is horrible. I hate the climate after the fires in 2017. And then I got up and cofounded Zero Hour. And now you know I'm gonna get up and make art that makes me happy and continue to fight for climate justice and do a push for the election to push Donald Trump out. You know, it’s more of just like I have despair, but then I just get up and do my thing. It's all you really can do.

Greg Dalton: If you’re just joining me, Jamie Margolin is a climate activist and co-executive director of Zero Hour, a climate action organization based in Seattle. Her new book is Youth to Power: Your Voice and How to Use It. I’m Greg Dalton. You’ve been quite open about experiencing shame and depression and alienation for being a career young woman in a world that erases people like you. As someone who has been shamed how do you think about shaming people on the other side of the climate divide?

Jamie Margolin: I feel like being alienated for an identity that you can't control versus alienating others for some their actions that they can control is very different. I got that question of it's like oh you hate it when people discriminate against you for being a lesbian. So, are you hating on the fossil fuel industry? And it's like it's different. Me being born a certain way, not hurting anyone, is different than people consciously choosing to go into a field consciously knowing they’re hurting people and hurting people like it’s almost like the whole blue lives matter thing. There's no such thing as a blue life. A cop is not -- being a cop is a profession that you choose and you can quit. I feel like the same thing goes for being a denier of climate change or working for the fossil fuel industry that’s something you can quit. That’s something you can change but an identity isn't. And I think in general though, in terms of shaming, shaming people in terms of environmentalism in terms of the individual it never works. But I feel like in terms of the industries like the fossil fuel industry 70% of all global emissions are caused by 100 corporations. We should be shaming them. We should be putting such an immense amount of public pressure that they either have no choice to completely change or to move out of the way and just to stop operation. Because I mean the entire West Coast is on fire so I'm not afraid to hurt a few feelings of the people causing this. You see how it's pretty different?

Greg Dalton: Yeah, I think some coal workers might say, I hear what you're saying about identity and born and that’s different than a professional choice. I think some coworkers would say they don’t feel like they have a lot of choice living where they are with the options in education.

Jamie Margolin: Oh, I'm not mad at the fossil fuel workers. I'm mad at the executives. I think that you know a lot of people don't have it to be clear, I don't shame like the person who has to work at the coal plant or the person who has to, you know, work on building these headlines or whatever because that’s like their only job, and that's all that they have. My anger is never directed at the individual. My anger is directed at those in power. So, I'm not angry at the people who mine coal because they had no other option like they're not the ones responsible for this. I'm talking about the executives because the coal miners did not see the documents about climate change and then bury it and start the propaganda machine. Like they were just trying to get to make a living. I have no hard feelings towards them whatsoever. I'm talking about the executives, the CEOs the CFOs the people in charge the propaganda people that they hired. The whole operation on top. The Wall Street people the investors the bankers. I'm talking about those people. I'm not mad at the little guy. I don't blame them at all.

Greg Dalton: And as we approach this election you wrote a book about power, youth taking power. How do you think about youth gaining power taking power now at this time in this tremendous upheaval of fires demonstrations in the streets, COVID. Where do you see power shifting?

Jamie Margolin: Yeah, so I wrote a book called Youth to Power: Your Voice and How to Use It which is a guide to being a young organizer for any cause. Even though it says youth in the title though, it’s actually useful to anyone of any age. It does have some things in the book where it’s like specific to balancing school or getting to college and stuff like that and like how to balance that whole system. But other than that, a lot of the advice in there is useful whether you're 10 or 90. So it's really for everyone. And I wrote it because I feel like young people have a power to take action and a power to make change, but it's not the power -- but leaders often misinterpret that power. I have a chapter in the book where I talk about like what power do youth have and what power don't. I made it very clear that we don't have the power of controlling like federal budgets. A lot of young people can’t vote yet or even only can it’s like they don't hold the political power in terms of office and don’t hold all these other things. So, when leaders are like oh young people would change the world it’s like well, and as I talk in the book like the power that we do have is to shift the needle towards change by shifting the culture. Because culture shifts cause shifts in law that’s why I am going to study, you know, film and television. Because that film and TV changes the culture and then culture changes the society and the laws. So young people have a huge influence on the culture, but we can’t actually physically pass, you know, we can't be the one to pass the Green New Deal. The people in power do. So, I get very frustrated when leaders are like oh youth, they’re so powerful you're going to save the world. I’m like literally the world's on fire you have to do that now. By the time I'm older, I would be old enough to even be in the position that they are in now it would be too late. So, I am very, you know, I wrote a book about a guide to being a young organizer and activists and to help young people take action, which means that I do genuinely believe in youth power. But I make it very clear in the book that it's not young people will be the ones to save the world single-handedly because I don't believe that, and I don't believe it's a fair burden to put on people who are just trying to get through high school or college or middle school in a dying world.

Greg Dalton: And Greta Thunberg was very clear about calling boomers and others out. That's a copout, don't put that on me. You trashed it you fix it. And she's been quite like right back at you. I wanna go to our lightning round with Jamie Margolin. And I’ll mention a noun and just get the first thing that comes to mind off the top of your head unfiltered when I say this one word or one phrase.

[00:20:12] Jamie Margolin: Okay.

[00:20:13] Greg Dalton: Jamie Margolin, what’s the first thing that come to mind when I say coming out?

[00:20:18] Jamie Margolin: Scary.

[00:20:21] Greg Dalton: The TV show Glee.

[00:20:23] Jamie Margolin: Santana and Brittany.

[00:20:26] Greg Dalton: Washington Gov. Jay Inslee?

[00:20:29] Jamie Margolin: Interesting and contradictory.

[00:20:35] Greg Dalton: The Republican Party.

[00:20:37] Jamie Margolin: Evil.

[00:20:38] Greg Dalton: Nancy Pelosi.

[00:20:43] Jamie Margolin: She said the green new dream or whatever and I do not like her for that. As well as other things.

[00:20:49] Greg Dalton: Erin Brockovich.

[00:20:52] Jamie Margolin: I don’t know who that is.

[00:20:55] Greg Dalton: She was – yeah, so she was portrayed by Julia Roberts won an Academy award for portraying her in a film before you were born.

[00:21:05] Jamie Margolin: Probably why I don't know.

[00:21:07] Greg Dalton: So that’s why you probably don’t know her. This is true or false. Every climate champion needs a good therapist?

[00:21:14] Jamie Margolin: True.

[00:21:18] Greg Dalton: Boomers trashed the planet and should feel guilty about it?

[00:21:22] Jamie Margolin: False. It's not as black-and-white. Some people some “boomers” like my abuela in Columbia like she grew up living off the land. She didn't cause the climate crisis. But like then there are other boomers like Mitch McConnell who absolutely did. So, it's not as black-and-white.

[00:21:37] Greg Dalton: Affluent American boomers. Last one. True or false. You allow yourself to fully feel the fear flowing from your understanding of how dark the climate science really is?

[00:21:51] Jamie Margolin: Is that a true or false question?

[00:21:53] Greg Dalton: Yeah. I mean, do you allow yourself to really embrace how dark the science is?

[00:22:01] Jamie Margolin: False for most of the time. Like true in the action that I take, but false, in that like I’m not in my daily life just thinking like we’re doomed, we’re doomed, we’re doomed. Otherwise, I can't like go to the store without having a panic attack. True in the sense of like when I act and when I push for policies, I push for them knowing the science. But it's not on the top of my mind otherwise I would just crouch into a ball and be crying. And I wouldn't even have the energy to do this interview.

[00:22:23] Greg Dalton: Denial is a coping mechanism that helps yeah.

[00:22:27] Jamie Margolin: I’m not denying it. I just turn that part of my brain off for the day that like during the day, unless I'm like actively doing a climate thing that I'm in that mode. But if I'm not, I turn it off and I just try to like okay right now I’m just going to the store and we’re not gonna think about it.

Greg Dalton: So, as we wrap up here. How excited are you about Joe Biden's climate plan?

Jamie Margolin: More excited than I was before he changed it, but still like tentatively like just cautious and like understanding that we’re going to keep pushing and keep pushing for more action. Like I mean, we need a Green New Deal, and I know I mean, I know how a lot of the corporate Democrats feel like Nancy Pelosi was like they call it the green new dream or whatever. And I don't appreciate that sentiment when literally half of the other coast is on fire and so the green new dream or whatever is what we need because the alternative, like Bernie Sanders said, solving the climate crisis is expensive as opposed to what. People always like it’s so expensive it’s so expensive as opposed to what. So, I just really feel like he could use some more work obviously I’m voting for him I’m pushing for him to win. We need to get Trump out of there because it would be absolutely catastrophic. I don't even want to think about it if Trump gets another four years. So, I'm very pushing hard to get him out of office and Biden is the one who's gonna get him out of office. So, we just need to keep pushing. Like I'm not confident I can’t just sit back and be like, well, he’s gonna handle it because I don’t think that. I think we’re gonna need to get him in and then pressure like hell.

Greg Dalton: Right. That’s what Obama said when he got in. Jamie Margolin, thanks for coming on Climate One.

Jamie Margolin: Thank you so much for having me.

---

Greg Dalton: Jamie Margolin is Co-Founder and Co-Executive Director of Zero Hour, and author Youth to Power: Your Voice and How to Use It. To hear more Climate One conversations, subscribe to our podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you get your pods. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. It really does help advance the climate conversation.

Greg Dalton: Kelli Pennington directs our audience engagement. Tyler Reed is our producer. Sara-Katherine Coxon is the strategy and content manager. Steve Fox is director of advancement. Devon Strolovitch edited the program. Our audio team is Mark Kirchner, Arnav Gupta, and Andrew Stelzer. Dr. Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, where our program originates. [pause] I’m Greg Dalton.