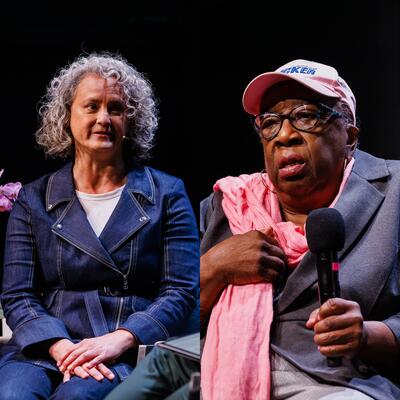

#Resist with Annie Leonard and Shanon Coulter

Guests

Shannon Coulter

Annie Leonard

Summary

What can you do if you care about putting your money to work toward a cleaner economy? Join us for a conversation on pressuring companies and personal brands.

Shannon Coulter, Co-founder, #GrabYourWallet

Annie Leonard, Executive Director, Greenpeace USA

This program was recorded in front of a live audience at the Commonwealth Club of California on April 19, 2017.

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: From the Commonwealth Club of California, this is Climate One changing the conversation about America's energy, economy and environment. I'm Greg Dalton and today we’re discussing whether your buying decisions can influence corporate behavior. When Nordstrom's was targeted recently for carrying Ivanka Trump’s fashion line, the company stopped carrying the merchandise citing poor sales. Ivanka Trump’s company said sales elsewhere are up dramatically since then. Consumer boycotts of companies have long been used as a tactic to vent frustration and could punish corporate behavior. Most have fizzled or failed. A few have succeeded. In the program today, we'll talk about using your pocketbook as a weapon and the role of individual action in addressing climate change and other issues. Our guests are two advocates. Annie Leonard has been an activist most of her life. Her video series The story of Stuff chronicles the life cycle of material goods and has been viewed online more than 50 million times. She is currently executive director of Greenpeace USA. Shannon Coulter is a reluctant and recent activist. For years, she was a marketing and communications consultant advising companies on their branding and digital strategies. During the 2016 election, she cofounded the #GrabYourWallet campaign focused on Trump family businesses. Please welcome them both to Climate One.

[Applause]

Welcome both. I'd like to start with you Shannon Coulter. Take us to the evening, the day in October of 2016, when you saw the Trump tape when he bragged on that bus with Billy Bush about sexually assaulting women.

Shannon Coulter: Yeah, I was – I think that happened on October 7th and I think on October 11th I was like many people and women in particular just experiencing a huge range of emotions about it, anger but also a lot of energy and not really knowing what to do with that energy but wanting to have some sort of formal response to it. I was raised by my parents on Nordstrom. We’re one of those families where, you know, Nordstrom is like almost a family tradition where we go to Nordstrom and holidays and, you know, in business presentations I would use them as an example of good customer service. And I was on the website one night and encountered a pair of Ivanka Trump boots, I think, and just started to feel some really deep ambivalence about the fact that one of my favorite companies was doing business with the Trump family at the time. She was campaigning for him very heavily on the campaign trail at the time and also marketing her fashions from the campaign trail and I started to feel like, hey this company that I love is profiting from a campaign that I regard to be overtly hateful toward women, toward people of color, toward the LGBTQ community, toward immigrants, toward a religious minority. I don’t feel good about that. I don’t know if I can do business with companies that are doing business with this family anymore. So I started to tweet about it and I got such an immediate and a strong response to those tweets that I felt a responsibility to do more. And then the other thing that was going on which is worth mentioning is that I was also at the time having memories come up of a time that I experienced sexual harassment in the workplace which, you know, in the grand scheme of things, certainly wasn't the worst case that I've ever heard of. Most women have, you know, stories they could tell you. But, you know, that was over 20 years ago. I didn't think that that was even still something that I could remember let alone have it come up so directly as a result of a news story. So that was interesting and that was definitely related to the birth of #GrabYourWallet.

Greg Dalton: Though there's lots of incidents of inappropriate sexual conduct in the workplace, sex scandals at Fox News, elsewhere, why was this time different?

Shannon Coulter: Yeah, it’s a really good question. There have been obviously, you know, sex scandals with respect to the church, with respect to the military too, so why did this particular one bring up those memories for me in such a strong way. I think it's primarily because both Donald and Ivanka Trump position themselves first and foremost as business people and that's how I think of myself too. And some of the companies that are doing business with the Trump family like Amazon and Zappos, you know, companies that I regard first and foremost as. tech companies almost are my clients, you know, in my backyard these are the people, you know, Musk, you know, Tesla these are people who could be in my business sphere on a day-to-day basis. And I think it was more personal to me because of that.

Greg Dalton: Is Nordstrom based in Seattle?

Shannon Coulter: Nordstrom is based in Seattle, yeah.

Greg Dalton: So there’s a Seattle connection here. Amazon, Nordstrom. Annie Leonard, you went to school and grew up in Seattle so to tell us how you came to The Story of Stuff which became such a big phenomenon and then we’ll get into the other topic.

Annie Leonard: With Jim Nordstrom, he even went to my high school.

Greg Dalton: Really? Okay.

Annie Leonard: I have been involved in environmental stuff since literally as long as I can remember that’s why it's such an interesting contrast here that we both end up resisting Trump from such different paths. I grew up in Seattle in a very environmentally-aware family, did a lot of hiking and camping, love the forest, thought I would become a forest activist when I grew up. I went to college in New York City which is an odd place for a forest activist to go but it turned out to be very fortuitous because that's where I started putting together supply chains. Growing up in Seattle, I would look at the clearcuts of the forest and as a kid I didn’t know about moderation of hydrological cycle or carbon sequestration, all these reasons that we actually need the forest. I would just look at those clearcuts and feel in my gut something was wrong. It was like a scene of violence. So I went to New York City and there I became mesmerized by the bags of garbage on the sidewalk in Manhattan. It is just incredible the bags of garbage and that's where I picked up my habit to the great embarrassment of my teenage daughter of looking in garbage wherever I go, because you can find out so much about a society by looking in the garbage. And so I started looking in this garbage on upper Manhattan, upper Broadway, and what I saw in there was paper. And I realized, oh that's where my forest is going into these garbage bags. I started putting it together. And so then I said, where did the garbage bags go when they’re gone. They were there every night, they were gone every morning. So I took a field trip to the landfill where New York City's garbage goes which is actually called Fresh Kills Landfill. And it was a life-altering moment that I will never forget where I stood there as a sophomore in college and looked out and as far as I could see was waste. And there were books and food and teddy bears and shoes and things that I had been taught to cherish and respect and not to waste. So it struck me two things. One is that we had built our economy on an unsustainable use of resources, and the second thing is that it was being kept secret. So right then and there I said I’m gonna figure out what is happening and I'm gonna tell everybody and I’m gonna change it. And that was in 1983 and that's what I've been doing since then.

Greg Dalton: So you're kind of, you know, an icon or a queen of don't buy too much crap you don't need. How do you feel about boycotts and consumerism as a lever for policy change and corporate change?

Annie Leonard: Ambivalent. I feel ambivalent about it. On the one hand, yay if people are thinking about using their dollars to promote good instead of bad, that's fantastic. I have somewhere between unresolved feelings to actual outright concerns though. One is I don't believe that changing your purchasing habits is a good way to drive change. When you actually look at the data about real-world change, I don't think that's a powerful lever to make change and I'm busy. I want to spend my time pulling the levers that yield the most change. When you look at boycotts in history the ones that have made change like the grape boycott, the Montgomery bus boycott, those have been deeply linked with organizing political action, movement building, social movements. That's the way that they make change. So I still have the practical thing but fine if it doesn’t make that much change still. It's great if it gets people involved and all that. My deeper concern is about the mindset or paradigm or the story that we tell ourselves about how you make change that is being promoted with consumer campaigns. And that is if we tell people buy this instead of this, it helps to make change. So, you know, go to Peet's instead of Starbucks because Starbucks has a store in Trump tower, or go to Ann Taylor instead of Macy's. I'm worried that that reinforces a narrative that concerns me in society which is that our greatest source of power is as consumers. And so we have an over-identification of consumers, and being consumers anyway in this country, I mean, it is the primary way that we communicate with each other, it's the primary way that we demonstrate our value, it's the primary way that we’re spoken to. And so it’s almost like we have two different muscles and our consumer muscle is so well developed because we are asked to be consumers all the time. I mean, so much that the wood consumer and human being are used interchangeably. It's like our primary purpose in life whereas our citizen muscle is atrophying. And so the problem with that is that when we’re faced with threats as enormous as we are faced today, climate change, that is literally threatening the future of agriculture on the earth, babies being born pre-polluted with 165 industrial chemicals already in their blood, the actual rollback of a century of environmental and social projects. These are enormous problems and if our consumer muscle is so validated and nurtured and stroked, then we think, well okay I’m gonna buy the Ann Taylor instead of Macy's. That’s not really commensurate with the scale of the problem and it's reinforcing that our biggest source of power is by making responsible consumer choices, which yes you should make responsible consumer choices, of course, but the real way that we make change at the level needed is by organizing, it’s movement building, it’s political power, it’s working together as engaged citizens for big, bold change. So that’s my explanation of what doesn’t quite sit right to me, we should buy this instead of this approach.

Greg Dalton: Shannon Coulter, you were kind of drafted into this by this moment. You didn’t sit back and say what’s the biggest way that I can make the most change on the world. But I’d like to hear your response to what Annie just said.

Shannon Coulter: I think it's an oversimplification. I think that the action that people are taking is not to shop at Ann Taylor versus Macy's. The action that people are taking is to communicate with some of the most powerful institutions in our world to say we don't support you doing business with extremists. This particular movement that I'm involved in is not a partisan one. It's not about Democratic versus Republican values. It's not about progressive versus conservative. We actually have a fair number of registered Republicans participating in #GrabYourWallet many of whom are LDS Mormons which I find really interesting. For them participation is an expression of their basic humanitarian values. And the action is to say to corporations to media outlets like Fox and Breitbart, you can't rely on my consumer dollar if you are going to also do business with extremists. If you are also going to be publishing this extremist rhetoric that then foments racism and misogyny and, you know, phobia in our society, you can’t count on me a woman as your core customer base if Nordstrom, for instance, you have an all-male senior executive team which they have. And I think it's more about that than it is about identifying as a consumer. I mean, I also personally find it really exciting to watch women in particular flex their consumer power. Women in our particular country haven't had a lot of it for very long and I think they're really coming into their own now with it. It's, you know, when you are born now as a girl you are pretty much expected to have a career in many, you know, circumstances which I think is, you know, it's new in my lifetime. It was new for my mom and I was the first generation of my family where it was pretty much expected you go have a job, you go make money. And so I get really excited when women flex that consumer power.

Greg Dalton: Do you think America as Annie Leonard said over-identifies as consumers, sort of blurs consumers and individuals?

Shannon Coulter: For sure. I mean, unquestionably. Absolutely. We’re way too materialistic as a culture. We see way too much advertising. But I don't think the answer is to pretend that that can somehow go away tomorrow. I think the answer is to use that in favor of the values that we hold dear. And it's also, I mean, elections only happen every so often. You can vote at the cash register every day. And I think it's a pretty easy thing to do for most people.

Greg Dalton: Annie Leonard, a lot of people come to Climate One programs and they, you know, say okay what can I do and as Shannon just said, you know, elections are every couple of years, not everyone is gonna go in a march and maybe you do that and the march is over and then what. So we spent money every day. Michael Pollan says vote with your fork. It does seem that purchasing is something that's accessible to people every day.

Annie Leonard: I absolutely am a fan of making responsible choices when we purchase. I wanna be super clear about that. I think we should buy the least toxic, least exploitative, least misogynistic, you know, least bad product out there. Absolutely.

Greg Dalton: But don’t fool yourself that you’re changing the world.

Annie Leonard: Yeah. But don't call that – yeah, don't call that changing the world. I get worried when I hear people say I wanna vote with my dollar because Exxon has so many more dollars than me. Walmart has so many more dollars than me. Why would I want to engage in a place where I am so outnumbered? I actually wanna get people to vote with their vote. And a lot of people don't vote. And in between elections, there’s a presidential election every four years, there’s lots of other elections and there's lots of other things we can do. I mean, one of the great things about such a gigantic mess that we’re in is that it is almost like an unlimited smorgasbord of activities of things you could do. So, you know, you can march, you can pass policies in your town, you can work for public transportation, you can work for healthy food in your schools. Literally you could do almost anything and not always good, but I like the things that build power. I like these things that shift the dominant power relationships in our society and that’s people coming together, getting to know each other, organizing, building power, engaging in the political process, engaging in our democracy. So yes, use your consumer dollars responsibly. But I see that kind of like floss your teeth, wash your hands after you use the toilet. These are like basic adult functioning. It’s, you know, do not buy explanation. Those are not political activism.

[00:18:32] Climate One. I'm Greg Dalton. My guests are Shannon Coulter and Annie Leonard. We took to the streets and asked people about boycotts and pressure campaigns. Here are some of their thoughts which may surprise you.

[Start Clip]

Male Speaker: Boycotts. Let me think. Yeah, I participated but not for a long time. Do I think they work? Yes and no.

Male Speaker: Okay. The one where everyone was going to quit buying gas on a Thursday that was done because everyone had to buy more gas on either Wednesday or Friday.

Female Speaker: I remember the grape strike when we all stopped eating grapes back 30 or 40 years ago. It definitely worked.

Male Speaker: I think the pushback against Amazon for its labor abuses, I participated in it and I would argue that it probably did have an impact but I'm back to buying from Amazon now that they appeared to have curtailed some of the worst warehouse abuses. Because something that works that directly impacted the Asian community as I do identify as Chinese American, I feel like it would influence me but as the same time I don’t know if I would do anything unless it directly affected me in any way.

Male Speaker: I wish – I’m about to say it wasn’t true but I tend to think that really legislation is much more effective. Consumer boycotts are always likely to miss out, hit things that happen to be high in tension without hitting underlying issues. They become less focused and moreover they tend to be short-lived.

Female Speaker: It’s something that I've actually struggled with on a personal level is I haven't divested yet from Bank of America.

Male Speaker: I use Wells Fargo. In a perfect world this wouldn’t happen. But I can’t approve my banking just because I don't like pipelines.

[End Clip]

Greg Dalton: That was a small sampling of consumers’ thoughts about boycotts and hashtag activism. We did a poll on Twitter. We asked people the question, do you think that boycotts and protests are useful in influencing and changing policy? 41% said no, 8% said yes for the symbolism, 23% yes for the visibility, and 28% yes they lead to change. Shannon Coulter, you're not focused on policy you're focused on corporate behavior. What has #GrabYourWallet accomplished so far?

Shannon Coulter: Well, 23 companies have been dropped from the list and the goal of a successful boycott is to get the companies on the list off the list. So that includes some big publicly traded companies like Nordstrom, Kawasaki, Sears, Carnival Cruise, Jenny Craig and in many cases I've actually been contacted directly by the companies on the list to say let's have a conversation about how to get off the list. And so those negotiations and conversations are always in play and that I can guarantee you wouldn't be happening if they weren't hearing from customers at scale. So the goals of our boycott are not policy-related, they’re not politics-related. They are cultural. They are about respect and inclusion and about changing our culture.

Greg Dalton: So you're engaging with companies. What do you think about people like Elon Musk being on the President’s economic advisory council, et cetera, is a place for that kind of engagement. Some people say, hey, it's better to have some sane people in the room. Well, I’m not saying Musk is sane, but –

Shannon Coulter: Yeah, I totally understand that line of thinking and I respect anyone who feels that way. I understand where they're coming from. I come from a place of feeling like for somebody like Elon Musk, again, somebody that I consider assertive in my sphere of work, Travis Kalanick of Uber, Sheryl Sandberg, to be in the same room and smiling and chatting with Donald Trump and having their picture taken with him, for me that feels like tacit approval of what he's done and what he’s said. And I completely understand somebody having a different interpretation of that. I have my own experiences. But for me it feels bad. And those executives, by the way, their companies are not on our boycott list. They’re on the FYI part of the list. The boycott part of the list is only for companies that have an explicit financial tie to the Trump family.

Greg Dalton: Annie Leonard, did Al Gore get used when he met with Donald Trump?

Annie Leonard: I sure think so. I mean, he went there. There was so much hype about Donald Trump is gonna listen about climate change, isn’t Ivanka Trump wonderful, thank goodness she's there and pictures of him leaving. And not only did nothing change but Trump was worse on climate. So I think exactly what you’re saying that it provides a cover or a lot of them call them enablers. If rational people with good values who understand science engage with him, it implies a consent or it makes him appear more normal than he otherwise is. And I believe in engaging with people with whom I disagree. But there is a limit to that. When someone is so morally repugnant, is so threatening to our communities and our values and our future, there’s a line at which you have to say I will not engage with you partly because there is no rational cell in your body with which to engage but also doing so gives my stamp of endorsement or validity to him. So I really do agree. It’s enabling – we have to be really careful not to normalize Trump and Trumpism.

Greg Dalton: Shannon Coulter, what does the world look like other than getting companies off your list, what's the bigger vision for #GrabYourWallet?

Shannon Coulter: The bigger vision is to become a more centralized resource for consumers to flex their consumer power in the direction of inclusion and respects. And we already see that with the sort of like preemptive leaving of Fox News that advertisers started to enact once the Bill O'Reilly stuff really started to play out in the news cycle. We saw big companies like Mercedes just preemptively leave because they knew that movements like #GrabYourWallet and Sleeping Giants were coming. They knew and Color of Change have been working on it for two years. So they knew that this momentum was building that organizers were getting together and talking about it to your point about, you know, the need for people to organize on the ground that's happening, you know, we’re all talking to each other. I meet with individual people. I'm flying to New York tonight to do more of that. I partnered with the Women's March. These people who are doing these movements are talking to each other and companies know it, and they're paying attention. So I think it looks like big, powerful institutions becoming more responsive to individual people and their lives and their values.

Greg Dalton: We’re talking about changing tolerance, social norms. Annie Leonard, we saw that very swiftly with marriage equality not so swiftly, but once it started to change it changes quickly. How's that happening with regard to fossil fuels and climate? When is getting on an airplane going to be like, you know, killing a puppy just like things that people just don't do.

Annie Leonard: Is that you think we’re United?

[Laughter]

Sorry. I think those social norms are changing all the time and there are different things that we can do to hasten that. One is that we can provide what scientists call social proof or social license. It’s like permission to change your behavior. And the way that you provide social proof or social license is by having other high-profile people or cultural influencers do these things. So the more that we can enroll people that others look up to to change their behavior, that's an important piece. Another thing though that we can do is work to make the alternative that’s environmentally sustainable just as easy and just as cheap. What I like to think of it is our whole economy is a big system, if we are trying to do the right thing and it's harder that's like sort of a metal detector to find a flaw in the system. If clean energy is more expensive than fossil fuel, that is a systems flaw. That doesn't mean we should keep using fossil fuel. We need to remove the billions of dollars of subsidies fossil fuels get that make it artificially cheap. We need to figure out how to change the system so that doing the environmentally correct thing is the cheaper and easier thing.

Greg Dalton: Shannon Coulter, you used to work for a solar company that was trying to do that. Do you think that you can see that day when solar is the default cleaner, it’s not just an elite thing for liberals on the coast?

Shannon Coulter: Yes. One of the most exciting things that I saw happening in the industry at that time which was about 2009 to 2012 was that the business case for solar was really strongly being made and that's why I got into clean energy. At that time, was that I wanted to help make that business case to big companies to do that. So I was less interested in the environmental narrative around clean energy and more interested in the business case and making it more accessible to residential consumers as well. Just, you know, hey you want to keep handing over $200 worth of your paycheck every time you get a power bill or that’ll put a couple of solar panels on your roof and not do that. So that was fun and exciting. And it's exciting to see how it's moved forward.

Greg Dalton: One of the most promising things I hear is ads for solar power on AM sports radio where it is clearly targeted at Joe six-pack and is targeted on price, not virtue. It's not like, you know, mom will think you're good. It’s a targeted at –

Shannon Coulter: Yeah. And we’ve seen some like unfortunate things. They did play out on that since like there's a little bit of a used car salesperson vibe to solar sometimes with like, you know, leasing deals I think, you know, proved to be a little bit. I think consumers are rightly skeptical about that sometimes. But I think that in general people now know that it is not – that there's a financial case to be made for solar.

Greg Dalton: We’re talking about activism and clean energy at Climate One. You just heard Shannon Coulter, cofounder of the #GrabYourWallet campaign. My other guest at Climate One is Annie Leonard, executive director of Greenpeace USA. I'm Greg Dalton. And it's time for our lightning round, brief questions and one a word or phrase answers. This first one is association. I will mention a noun and you will give me the first thing that comes into your mind unfiltered.

[Laughter]

Annie Leonard, Wells Fargo.

Annie Leonard: Standing rock.

Greg Dalton: Shannon Coulter. L.L. Bean.

Shannon Coulter: Linda Dean.

Greg Dalton: Who’s a family member that you want off the board.

Shannon Coulter: Board member.

Greg Dalton: Board member. Annie Leonard, a consumer product in your home that you don't want anyone to know about.

Annie Leonard: Pantene hair conditioner.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: Shannon Coulter, a branded thing in your home that you don't want us to know about.

Shannon Coulter: My New Balance sneakers. I bought them before the election, and I haven't quite been able to get rid of them yet.

Greg Dalton: Annie Leonard, Alec Baldwin.

Annie Leonard: I love him. I just – total love.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: Shannon Coulter, Melissa McCarthy.

Shannon Coulter: Seven7, her great fashion line.

Greg Dalton: Didn’t know that she had one. Maybe Spicer will start wearing it. Okay.

[Laughter]

This is true or false. Annie Leonard, some environmental organizations enable corporate greenwashing.

Annie Leonard: Totally.

Greg Dalton: Shannon Coulter, some environmentalists turn people off with their righteousness. (00:33:04)

Shannon Coulter: 100%. Those are too easy.

Greg Dalton: Annie Leonard, true or false. One Greenpeace slogan is “we have no permanent friends and no permanent enemies.”

Annie Leonard: True.

Greg Dalton: Shannon Coulter that slogan, true or false, also describes Donald Trump.

[Laughter]

Shannon Coulter: Say it again.

Greg Dalton: “We have no permanent enemies and no permanent friends.”

Shannon Coulter: True.

Greg Dalton: Annie Leonard, true or false.

Shannon Coulter: So I have something in common with Donald Trump then?

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: That’s, yeah, Greenpeace and Donald Trump has something important in common. True or false, Annie Leonard. You are happy when Donald Trump took the United States out of the trade deal known as TPP or the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

Annie Leonard: True.

Greg Dalton: So you agree with him. Shannon Coulter, true or false. Donald Trump and his three oldest children signed the 2009 letter published in the New York Times supporting an international climate agreement.

Shannon Coulter: False.

Greg Dalton: Actually he did.

Shannon Coulter: Didn’t know that.

Greg Dalton: Right before Copenhagen the Trump family signed a letter saying they wanted a deal in Copenhagen. Shannon Coulter, true or false. A year from now the Trump brand boycott will be like yesterday's fashion.

Shannon Coulter: True. Not a hot brand.

Greg Dalton: Annie Leonard, true or false. Shannon Coulter might consider joining an existing organization pressuring corporations to be better citizens rather than creating yet another new group that runs on charitable donations.

Annie Leonard: I don't know because I’ve never asked her that. Might you consider joining another group rather than starting your own?

Shannon Coulter: Possibly, yes.

Annie Leonard: Possibly, yes.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: Last two. Shannon Coulter, true or false. You would secretly like Annie Leonard to teach you how to hang off a bridge over a river –

Shannon Coulter: Yes.

Greg Dalton: – as an oil tanker come steaming your way.

Shannon Coulter: I would pay money to do that, yes. (0:35:00)

Annie Leonard: I’ll teach you for free.

Shannon Coulter: Sweet.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: True or false. Annie Leonard, you’d like to go shoe shopping with Shannon Coulter.

Annie Leonard: I have enough shoes but I'd love to go out for tea.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: Alright, that ends our lightning round. Let’s give them a round for getting through that.

[Applause]

[CLIMATE ONE MINUTE]

Announcer: And now, here’s a Climate One minute.

It’s one thing to avoid buying products from companies with a poor record on climate. But what would you risk to stop those companies from doing business at all? Georgia Hirsty is a National Warehouse Program Manager with Greenpeace. In 2015, she suspended herself off the St. John's Bridge in Portland in an attempt to block a Shell oil rig, the Fennica, from traveling to the Arctic.

Georgia Hirsty: We were 13 people across the span of the St. John's Bridge. And we were about 70 feet apart from each. When the Fennica came towards us, you know, I don't know exactly the distance between that drawbridge but it steamed right up to us and I hailed the Fennica on the radio and said in maritime protocol, that “This is the activists under the bridge and you are on a collision course and you’re putting people's lives at risk, please stop.” And they eventually radioed back and said “This is the Fennica we’re not going to stop so move” something like that and then I repeated my message we obviously weren’t in a position where we could move. And then they confirmed that they had stopped and you could see that the ship had stopped they no longer had a wake but there was this moment that seemed like kind of forever where everyone was waiting with bated breath. You know, the water was filled with kayakers there were, the activists on the bridge and though we couldn't speak or talk to each other we were too far apart, you could feel the kind of the tension in that moment while everyone is waiting to see what the Fennica would do and whatever time in reality passed I don’t know. Eternity passed and then the Fennica slowly started to turn around and when it got about 90 degrees in the other direction you just heard before I even could react, you could hear the uproars of cheering from the quayside and from the water and then it turned all the way around and went back to its port.

Announcer: Georgia Hirsty is a National Warehouse Program Manager with Greenpeace. She told her story at Climate One in 2015. Now back to Greg Dalton and our live audience at The Commonwealth Club.

[END CLIMATE ONE MINUTE]

Annie Leonard, tell us about some times when Greenpeace has pressured companies and then collaborated with them. I’m particularly interested in first, Facebook and then we'll talk about Kleenex.

Annie Leonard: So there are lots of times that we do that. In fact, I recently spoke in a business conference and somebody asked me on the panel, are we better at confrontation or collaboration. They said should we see was a good cop or bad cop. And I said we’re really good at both so it’s largely up to you. We’d rather sit around a table than hang from a crane but we’ll do whatever it takes. And so Facebook is one. The Cloud is often seen as something clean because those Apple billboards look so clean and nice and their products are all shiny and all this but the Cloud is actually an enormous consumer of energy. If it was a country it would be the fifth largest country in terms of the amount of energy it produces and carbon releases. So we decided that we would do a campaign against large Internet companies to get them to commit to renewable energy. And the reason was that would shift the market if all of these companies started demanding renewable energy then states would have to invest in renewable energy in order to provide it and attract them with the big Clouds to Kansas or North Carolina, wherever they’re going. So we did a big campaign against Facebook, it was Unfriend Coal. We said Facebook, Unfriend Coal. At first they did not respond or they did not respond the way we wanted them to. They have now completely committed to using renewable energy as has Google, eBay, Etsy, Apple. All of these companies and we now have very good relationships with them. We’re still working on Amazon, we’re getting there. We’re not quite there yet but we have great relationships where they come to us and asked for information, we share strategies, we speak together on panels. Actually we spoke together on this very stage before. So it’s a great example as where we to have this, we started by doing research. We always politely ask first. If we don't get the response, we will totally do a campaign on them. We will leverage brand vulnerabilities. But our goal is to sit at the table and find solutions.

Greg Dalton: And then there's another campaign, a clear cut aimed at Kleenex.

Annie Leonard: Yeah, this is just one of there are literally dozens of these campaigns that have gone through this route. We did a campaign against Kimberly-Clark because it was clearcutting old-growth forest in the boreal forest in Canada for disposable tissues. I mean it was absolutely crazy. And so they have a very, very weak sustainability policy that still allowed them to do this. We did a campaign against them. It got extremely antagonistic for a while. Finally, they admitted that they could do better and they asked us to the table and work it out. And they are doing much, much better now and we actually have become friends with them.

Greg Dalton: When you started that campaign though the people who are involved in sustainability and they’re all large corporations have these people now said, hey wait we’re the good guys, we’re doing more than that other company over there. And Shannon Coulter, that probably comes to company you address as well. So first Annie Leonard, lot of these companies think, hey, we’re good. They like, people like to themselves stories that they’re good. We’re not as bad as those our competitors. So how do you deal with that when they think like, hey, why are you attacking us, you know, we’re doing our part incrementally, slowly, we’re not the worst.

Annie Leonard: Well the thing is, the bar cannot be not as bad as someone else like we are really in a crisis in terms of ecological boundaries. The bar has to be the best we can possibly be. So I like to tell these companies they should welcome us. If we were consultants giving them the kind of information we give them, we will charge a fortune. Like how fortunate for them that we are calling them up and offering to give them free information about flaws in their supply chain and what they can do about it. So they can either fight us and then go pay somebody else who will give them that or let us in and then let’s talk about it and make it better so. I think that they should welcome us and see it actually as a sign of affection. When I was just at this business conference, I said you know, we’re trying to help you be better. You know, if my kid got a C in Physics, is it a sign of my investing in her to succeed, if I said that’s fine, C is fine. No, I’m saying an A, let’s go buddy. Same thing with these companies, you know, I said in this business conference, most of you I would like to continue existing. Exxon was in the room so it wasn’t everybody. But most of them I would like to continue to exist and I’d like them to continue to exist in a way which also allows for humanity to exist. And you know, I don’t think that’s asking too much.

Greg Dalton: Can you have empathy for someone who spent their career working at an oil company and thought, hey, we’re providing a service that runs the economy. Can you or does that person you think that's a bad person?

Annie Leonard: If it was 1971 maybe but at this point or if they really have no other options. I mean sometimes you’ve got to put food on the table and you're trapped, I totally get that. But if you have other options, if you have education and you have resources and you know how to read science you really need to get out of the fossil fuel industry.

Greg Dalton: Shannon Coulter, can you have empathy for some these corporations. They’re like hey, we have pressure from Wall Street I’m just trying to do my job, I’m part of a system, I’m not a bad person I kind of agree with you. But hey, if we stop selling this brand then we’re gonna have every other cause knocking on our door saying what about this, what about that? Can you have empathy for that corporate person?

Shannon Coulter: Yes, definitely. I was just still thinking about your question about the person who works at the oil company. My dad worked at an oil company for his entire career and, you know, his daughter ended up working in solar to some extent. So I feel like and it’s been really interesting to watch oil companies start to buy, you know, alternative energy companies, clean energy companies. There's been some activity around traditional fossil fuel companies buying clean energy companies because ultimately they can see the writing on the wall. Saudi Arabia is one of the countries that’s most interest in clean energy in the world right now. They know which direction things are going and they just want to make a profit for their stockholders ultimately. So they're moving in this direction in terms of what I'm doing, the direction I see things moving is just accountability like big corporate entities are becoming more accountable to everyday people in a way that they haven't been before. Corporate social responsibility is a huge trend in the corporate world right now because consumers are speaking up because it’s a function, I mean this boycott is a function as much of our choice as consumers as it is anything else. We have nothing if not choice, right so it's easy to make consumer choices and say hey, this company is more transparent on their supply chain than this company, I’m gonna shop with them. Or this company has 50% women on their senior executive leadership team and that matters to me so I’m gonna do business with them. We have so much choice that it's naturally pushing these big formerly not very responsive entities toward responsiveness and towards transparency and toward accountability and that's what I get really excited about.

Greg Dalton: How do you talk to your dad about climate change?

Shannon Coulter: My dad is actually extremely supportive of the clean energy movement and knows exactly what's going on in terms of the climate. And we have a lot of political discussion that we’re usually singing from the same hymnbook on that. r

Greg Dalton: Any guilt about his role in it or is it different that well we didn't know back then and we know, I wouldn't do it now what we know now.

Shannon Coulter: My dad was the first person in his family to go to college and he put himself through school. So now there's not a lot of guilt there, there’s a lot of pride in having, we ended up a lucrative corporate gig and put his two daughters to college, you know, himself so we didn't have to work like he did through school. And, yeah, no guilt there.

Greg Dalton: Annie Leonard, any difficult conversations in your family about climate or what you're doing?

Annie Leonard: No, I’m really lucky my mother was also the first person in her family to go to college, and what she said is she just wanted us to be educated because you have so many opportunities if you’re educated. So she scrimped and saved and took out student loans and sent me off to this Ivy League college. And when I called her up and said mom, I found my passion and it's garbage. She said, I don't understand but good. And, you know, never tried to steer me in a different path, so I’m very fortunate.

Greg Dalton: Have you made any other sacrifices because of what you know about climate the very serious situation any sacrifices?

Annie Leonard: The things that I've done to reduce my climate footprint or actually life enhancers they're not sacrifices. And the biggest thing that I do that reduces my climate footprint and also makes my life so much richer is I live with a very strong sense of community. I have all my best friends and I over the last 20 years have gotten six houses in a row. And we have taken all the fences and we share everything and so because of this we have one lawnmower, one scanner, one power drill like one ladder so that we don’t have to all own these things. Also because of this, if I’m in the middle of cooking and I don't have eggs, I don’t have to drive to the store I can just go to my neighbor’s house and get it. When my daughter wants to learn how to play tennis I can borrow a tennis racket. All of these things if you live in community, you have such a richer life and you need to earn and spend less money and also not store all that crap because somebody else can store it for you. So for me that’s the biggest where I have reduced my carbon footprint and it has not been a sacrifice at all.

Greg Dalton: Sounds like a scary level of intimacy.

Annie Leonard: They’re individual houses. Which helps a lot.

Greg Dalton: Shannon Coulter, what have you done to modify your lifestyle based on what you know about climate?

Shannon Coulter: Yeah, my husband and I have kept our lives at a scale that I would describe as pretty small. Even though we could right now afford to move into a bigger house we live in a fairly tiny little house in Stinson Beach. And we deliberately, you know, don't buy a lot of stuff we like to travel instead of buying things. And I'm really grateful, you know, there've been times in my life when the temptation to make the scale of our life bigger has been there. But, you know, when we go when like when Grab Your Wallet happened I suddenly felt very grateful that we hadn't, you know, because it gave me more freedom and flexibility and actually let me use my voice more loudly than I might have otherwise.

Greg Dalton: That's one I’ll just confess. We’re still working on that in my family the scale and some of that stuff. So still a work in progress. Annie Leonard, a lot of this comes down to the drivers the economic drivers are the need for continual economic growth. You know the Club of Rome did this report back in the 70s, which talked about climate economic growth that's what drives all of the retirement plans of people listening in this audience. Quarterly compounded growth of stocks more, more, more and we talked about a lot of systems change here. Changing water systems, food systems, but that's the system that I think is scary to talk about because it sounds like you’re a communist, right. You question that you start questioning markets, do you go there?

Annie Leonard: I do go there actually the final story of film and the story of subseries is called The Story of Solutions. And what it talks about is that there are some kinds of solutions that provide relief or make improvements within the existing system that ran. And some of those are great solutions, you know, things like getting lead out of gasoline. That did not fundamentally change the system but that was a very good thing and many children have higher IQ because of it. But those will only take us so far and so what I argue in this film The Story of Solutions which is on YouTube is what we actually need to do is look at deeper, more transformative changes of the whole economic system. And one of the big ones as you mentioned is this absolute obsession with growth. Currently, the way that we measure success as a society the way that all economies do is just by economic growth, which is a measure of how much money changed hands is, which is much too closely linked with how many resources you've extracted, produced, consumed and disposed. And so we need to decouple prosperity from running materials through the system and we also need to have a more holistic approach to how we view our society. One of the problems with economic growth is it doesn't differentiate between expenses that make life better, and expenses that make life worse. So if you build a school or you build a prison or if you spill hazardous waste, or if you clean it up. It doesn't matter. You get the same points for either one. And so we need something like a genuine progress indicator as one model that looks at how much economic activity is happening and how educated are the kids and how clean is the water and how strong our communities. You know, a broader way of analyzing and assessing how we're doing, because right now we only measure one tiny little aspect of what we’re doing. And growth and well-being go together for a while, you know, if you, I think about Little House on the Prairie remember that episode where they got a penny and a piece of peppermint again for Christmas and they were so excited they have no glass in the windows. Like in those days, more stuff actually did make you happier. Growth was a good thing but there comes a point at which increased growth starts undermining our well-being. And if we’re focused on growth instead of our well-being, we’re missing it. We need to focus on well-being and growth is one of many avenues to get there but growth is not the goal and in of itself.

Greg Dalton: We’re talking about social change and advocacy with Shannon Coulter, cofounder of Grab Your Wallet campaign and Annie Leonard, Executive Director of Greenpeace USA. I'm Greg Dalton. We’re gonna invite your participation with one, one-part comment or question at the microphone back there. Please briefly identify yourself. So go, yeah.

Male Participant: Hello, my name is Aaron Choate [ph]. Thank you all for a great conversation. Annie Leonard you mentioned your visceral experience of clearcuts in the Pacific Northwest. I’m also wondering about the influence of the WTO protest the Battle in Seattle and whether that's influential for both of you. And then how those have been connected to more recent activities such as the occupy movement, the Women's March.

Greg Dalton: Annie Leonard.

Annie Leonard: Yeah, it was cool to have the devotee of protest in Seattle because all of my friends came to my hometown. It was great and for me the biggest impact that _____ [00:53:10] was showing me the power that comes if we can work across silos. You hear about the teamsters and the turtles we had labor union and Third World farmers and reproductive justice activists and so many different people coming together. And when we come together it's really true that the people united will not be defeated like it’s actually true. But we have to get together and talk and listen. So for me that was the biggest impact of that and then we won, that was also nice.

Greg Dalton: But wasn’t Seattle quite violent?

Annie Leonard: There was a small group of people that were violent towards the big chain stores that they felt were sucking money out of the community. There actually was a political astuteness to it. They didn’t go after the local independent stores. Nonetheless, we can't let a small group of opportunists hijack a really powerful people power moment and they will try to do that.

Greg Dalton: Let’s go to our next question. Welcome.

Female Participant: I’m Eloise Hammon [ph]. And I’m wondering given that we can't count on much help for the climate from the White House. Do you think that we've reached a tipping point with respect to corporations picking up the ball?

Shannon Coulter: Do you want to go first?

Greg Dalton: Shannon Coulter.

Shannon Coulter: No, I don’t think we’ve reached the tipping point. I mean, I think that corporations can continue to work on the issue together in really powerful visible ways. There was an alliance recently of corporations of like 500 I believe. Nike and Coca-Cola and like huge, huge, corporations coming together saying, you know, we are committing to going 100% clean energy in the future. I think that we’re gonna continue to see that and it's important. These next, I mean 4-8 years I don't even know what to say about that I’ll let Annie speak to that. But I mean we have a climate denier the head of the EPA and the EPA staff aren't allowed to even say the phrase climate change anymore so it's pretty egregious. I can only hope it's a blip.

Greg Dalton: But some people are looking to companies to stay in Paris for example, rather than, there’s not gonna be federal policy the corporations want to do the right thing because their customers want to, their employees want to do then they’ll be the voice –

Shannon Coulter: Yeah, I mean just like we saw with the Super Bowl advertising, you know, that was all geared toward inclusivity and respect for immigrants. America is a nation of immigrants. These companies know that the future of their bottom line are people younger than me, so I think that they are, you know, they know which messages resonate and which don't and fortunately, people younger than me care a lot about climate and environment. So they know that.

Greg Dalton: Let’s go to our next question for Shannon Coulter and Annie Leonard.

Female Participant: Hi, Meagan Morris, HIP investor and full disclosure, what I do for a living is try to get people to vote with their dollars with their consumption choices and their investment choices. And the reason I came tonight is because an invite that said, oh have you heard of anyone switching their bank account because of the Dakota Access Pipeline, neither have we. And I actually have been telling people, you know, to switch bank accounts for three years and feel for the first time that people are listening and they’re taking action. And I have seen just in the last couple of months a lot more people actually moving their money than in the last three years when I've been having conversations. So I just like to see your thoughts recently, you know, you spoke a little bit about corporations realizing that everything they do is transparent and seeing a lot more momentum across the board. Can you talk about the momentum and everything that you’ve spoken about tonight recently in the last couple of months.

Greg Dalton: Shannon Coulter, other issues, yeah.

Shannon Coulter: Yeah, well that’s I mean what you’re describing is happening in my household so it’s near and dear to my heart. And I think it’s happening more than the companies involved would like to admit that it's happening. And thank you for your work. I think it's really important. It's all connected to this conversation of, you know, how where do we put our dollars, how does it align with our values. We have a ton of choice, companies need to start getting transparent about their values so we can make decisions about how well the aligner down the line. And if you don't do that these days that translates to opacity if you're not willing to say what those values are and be on the record about it, guess what I’m gonna assume the worst and I’m gonna go with the company that does. So it’s absolutely imperative, I talked to a woman today who is, you know, organizing this group of high-powered European women investors and they’re creating an organization to talk about, you know, divesting their investments from companies where the values don’t align and divesting from companies that don't have, you know, strong women leadership. And I think it's happening at a pace and a scale that is really hard to even estimate right now. There's so much energy for it.

Greg Dalton: Let’s go to our next question. Welcome.

Female Participant: Hi, my name is Melissa Miranda and I’m an entrepreneur in residence at Venture capital fund. For Annie Leonard, so how do we solve the fact that we still need clothing and we still need stuff in a way that’s compatible with your values? And we have to assume that there are not enough hand-me-downs to go around because clothing wears out and we can’t all live next to our six best friends and share everything.

Annie Leonard: So I wanna be clear, I'm not opposed to clothes. I think clothes are something that we will need after the transition to a clean economy and even during the transition to a clean economy. I'm not opposed to consumption. What I'm opposed to is consumption that trashes the planet, you know, consumption that pushes us beyond ecosystem boundaries. I'm opposed to consumption that poisons us there’s a lot of hazardous chemicals in our everyday products from our carpets, through our upholstery, to our Pantene hair conditioner. So I'm opposed to products, poisonous. I’m also concerned about consumption that we can confuse our sense of self-worth or our sense of meaning and purpose. That's where I think our relationship to consumption has gotten out of hand. I have totally no problem with people buying clothes and shoes and food and coffee and whatever else they need, but if that consumption is trashing the planet poisoning us or if we've gotten confused about our sense of self-worth being associated to that consumption, that’s where it worries me and I think things start to go astray.

Greg Dalton: I interviewed Yvon Chouinard, the founder and owner of Patagonia. And he said, yeah, I’ll admit it that lot of shopping is because people are bored.

Annie Leonard: Right. They’re bored, they’re looking for meaning, they’re looking for identity, I mean there’s a lot of studies about the reasons why people shop. I mean Juliet Schoris an incredible academic who wrote a book “The Overspent American” that looks at why people buy stuff it’s almost never because they need that thing. And that the environmental, economic, emotional and social toll of buying excessive stuff that we don't need and looking to consumption to fill other human needs is just not, it’s neither sustainable nor fun. So I’m saying let’s do something that is sustainable and fun and that’s to buy less stuff and engage with each other in community instead, dressed.

Greg Dalton: Let’s go to our next question for Annie Leonard and Shannon Coulter.

Female Participant: Catherine Tynan [ph]. I have a small consulting practice here in San Francisco. None of you have mentioned healthcare and the impact of choice on healthcare and then the impact of the environment or the healthcare on the environment. A lot of people are working in this country because they need access to healthcare. A lot of people are making Faustian bargain with companies because they need healthcare. And do you have any thoughts on how this sort of Faustian bargain is disturbing the system in the U.S.?

Annie Leonard: I actually do. I have lots of thoughts on this. When people ask me what's the number one thing that we could do to improve sustainability in this country. I say provide national healthcare. Without a doubt that is the number one environmental policy that we could adopt. And the reasons are the very things that you said. There are so many people that are like bonded labor tied to soul killing and planet trashing 40 plus hour week job to get healthcare. It’s bad for the planet it's bad for our emotions and we have to go to the mall and go shopping. My sister works like crazy and she told me she goes shopping because sometimes she just wants to be somewhere where the most challenging thing is that her shoes match her purse like it’s just such a relief. If we were free to choose our own hours, if we were free to choose to invest in community rather than continuing to work which we could do if we had national health insurance. We would see a reduction in our carbon emissions. We would see a reduction in consumer debt, we’d see reduction in social isolation. I literally think that's the best thing we could do for our country which is why I think one of the best leverage points if we want to figure out how to live sustainably is fight for national healthcare.

Greg Dalton: I’ve never heard that one before, it’s really interesting. I’d like to hear from each of you, climate is often thought as a very intellectual, cerebral factual concern. Annie Leonard, when have you had a real gut experience about climate that really hits you at a different emotional level about the magnitude of it or perhaps the all or the promise of it, but something that was, other than when you went to Fresh Kills and saw the garbage.

Annie Leonard: Well, I travel a lot and one of the things I do every place I go is ask people, is the weather changing and what's that like. And it is amazing every single place that I go people say that. I was in Canada and they said their forests were threatened because the winter no longer gets cold enough to kill a certain beetle that is eating away at the trees, but usually the population is kept in check in the cold winters and so their forests are in trouble. I was in South Africa and they said a certain fruit wasn't bearing fruit because the birds or bug something that flies didn't come to pollinate it because the weather was off. I was in Bishop and they said it used to be 2 feet of snow there every winter now it's a couple inches. Like everywhere you go and so what really strikes me is that this is not something in the future. This is not something for our children. It is here, it is now. And if you just start asking people, there are so much evidence. I'm glad you said it's factual because I hear so many people say he doesn't believe in climate change. I’m like, it is not a belief system. Belief has nothing to do with this and so I think we need to push back when we see someone doesn’t believe in climate change. It’s not, it has nothing to do with beliefs.

Greg Dalton: People don’t accept. Shannon Coulter, have you experienced climate change in a visceral way?

Shannon Coulter: Yeah, it’s always been emotional for me. I mean I, when I was a little girl founded a club called the Ladybugs in my neighborhood to pick up garbage from the forest floor, that was our mission. And it's, you know, it was emotionally upsetting to me to see that garbage on the forest floor. And it's not, you know, it’s been a through line in my life that emotional reaction to what we are doing to our planet it’s always been like the core of it is emotional not intellectual. It's on an emotional level it's really upsetting and not understandable to me to see what happens. I was babysitting once for my best friend's son and he was just like maybe four at the time and I was reading him a bedtime story. And it was like a really sanctimonious bedtime story about climate change. And he looks up at me and he said, Shannon, if we know that cars are bad for the environment why do we still drive them? And I had no good answer for him I had none. And it really brought me back to that place of like gosh, you know, a child can understand why, what we’re doing is wrong and bad, why don’t we stop.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, people look back at us and say you knew what were you doing, what were you thinking. The way that some people say the way that we look back at slavery, how –

Shannon Coulter: Yeah, I was just gonna say the best explanation I've ever heard is how intertwined slavery was with our economic systems and how much work it took to push out of that.

Greg Dalton: And yet it didn't cost that much it didn't have the economic disruption that people argued at the time that it would have.

Annie Leonard: Can I just give an example on slavery. There was a very interesting debate during slavery about those who said we should stop slavery by not buying slave produced goods. It was called the free produce movement and they said well they won't participate in the economy by buying slave produced goods. There were other people that said the many, many hours that you're gonna spend going out of your way to not buy slave produced goods could be fighting slavery. And it was a very interesting debate so there’s corollary with where we are right now.

Greg Dalton: Go direct. We’ve been talking about the impact of personal purchases and individual action in addressing climate disruption and other issues. I'm Greg Dalton. And my guests were Annie Leonard, creator of The Story of Stuff and Executive Director of Greenpeace USA. And Shannon Coulter, cofounder of the #GrabYourWallet boycott aimed at Trump family businesses. Podcasts of this and other Climate One shows recorded with the live audience are available wherever you podcast. When you download one, please leave a comment or give us a rating. We want to know what you think of our conversations on energy, food, water, technology, and more. Thanks for joining us. We'll see you next time everybody.

[Applause]

[End]