Heroic Lives of Climate Defenders

Guests

Alfred Brownell

Laura Furones

Nicole Figueiredo de Oliveira

Sarah Benn

Summary

Climate advocacy is a dangerous business. According to Global Witness, every week, somewhere in the world, between three and four environmental activists are killed. And that’s just from the numbers that are reported, it is suspected that those deaths are undercounted.

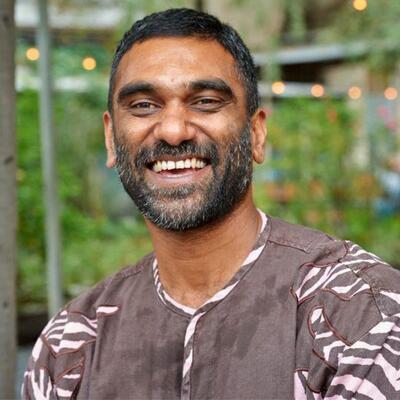

Alfred Brownell is president of Global Climate Legal Defense. He was born in a small village in rural Liberia and went on to get his law degree in the United States. Then he returned home to help write the country's environmental laws. But advocating for the enforcement of those laws soon became dangerous.

In the early 2000s, the Liberian government began leasing forest land to foreign companies to clear cut and replace with palm oil plantations. These tropical forests weren't far from where Alfred had grown up.

“The destruction was unbelievable. I mean, just the huge amount of timber that were being destroyed, the rivers, the secret sites, the burial grounds, the traditional areas, the impact on the communities, the impact on food security, just the brutality of local officials against the communities was despicable,” says Brownell

Alfred Brownell worked to stop the destruction, trying to enforce the laws he helped write. In the process, he says his own government put him under surveillance, and monitors the palm oil industry sent to see the destruction left. Then, Brownell says he was ambushed…

“We were ambushed along the road. The company, private militias and securities and some of their employees set up a massive roadblock. And when we arrived at the roadblock, they were looking for us,” says Brownell. “There was about a hundred plus of them. And they had machetes. Some of them had guns in their hand.” Then came a really chilling moment, “They lit the bonfire. They put a pot on the fire and said, we're going to cook you. And they pointed to the fire.”

The local chief decided he did not want Brownell killed on his land, which started an argument among the men and allowed Brownell and his crew to escape alive.

Alfred Brownell moved with his family to Boston. He's now teaching human rights at Georgetown Law in Washington, DC. His ordeal prompted him to found Global Climate Legal Defense in order to provide legal support to people protesting environmental injustice, even other lawyers, like himself.

So how does violence like the kind Alfred Brownell and other climate defenders face get perpetuated? “The truth is that typically the large majority of cases result in no consequences at all,” says Laura Furones, Senior Advisor at the Land and Environmental Defenders Campaign for Global Witness.

In 2020, Brazil granted the Turkish company Karpowership permission to bring in four offshore gas fired power plants. When these massive, floating power plants started showing up in the Sepachiba Bay, local fishermen were worried.

That’s when Nicole Figueiredo de Oliveira stepped in. She's a lawyer and the executive director of Arayara, a Brazilian non profit with the mission of stopping fossil fuel expansion in Latin America. Figueiredo de Oliveira was able to get a court order suspending Karpowership’s operations in the bay. In return, the Karpowership sued her for defamation. The lawsuit is still in progress.

Dr.Sarah Benn was sentenced to 32 days in prison for participating in a sit-in infront of the Kingsbury Oil Terminal in the UK. Perhaps worse than the jail term, a medical tribunal determined that her actions brought “disrepute” to the medical profession and suspended her registration. Dr. Benn is still fighting this charge. She says, “The climate emergency is a health emergency, not just in the global South, but all over the world..”

Episode Highlights

3:25 - Alfred Brownell on his experience in the Liberian tropical forest

7:07 - Alfred Brownell on being ambushed

11:21 - Alfred Brownell on surviving the ambush

15:00 - Laura Furones on why violence is so prevalent against climate defenders

23:04 - Nicole Figueiredo de Oliveira on Karpowership floating power plants

25:52 - Nicole Figueiredo de Oliveira on being sued by Karpowership

34:03 - Nicole Figueiredo de Oliveira on what a climate defender means to her

38:44 - Sarah Benn on being sentenced to 32 days in prison

41:53 - Sarah Benn on what climate actions are most effective

53:08 - Laura Furones on how we can address violence against climate defenders

What Can I Do?

Resources From This Episode (4)

Full Transcript

Note: Transcripts are generated using a combination of automated software and human transcribers and may contain errors. Please check the actual audio before quoting it.

Greg Dalton: I’m Greg Dalton.

Ariana Brocious: And I’m Ariana Brocious.

Greg Dalton: And this is Climate One.

[music change]

Greg Dalton: The 29th annual UN Climate Conference — or COP — wound down this week in Azerbaijan. If you didn’t hear much about it, there’s a reason. There weren’t many headline-making breakthroughs this year.

Ariana Brocious: The host country for these international climate conferences largely sets the agenda. And this is the third year in a row the conference was held in an oil rich nation. And that might have put the brakes on progress.

Greg Dalton: Right. The growing influence of fossil fuel interests on climate negotiations has more people questioning whether the whole process needs to be revamped. In an open letter to the UN, more than 20 senior climate officials said these global talks are quote: “no longer fit for purpose.” And the people who signed it are big names: like former UN Secretary General Ban-Ki Moon and former UN climate chief Christiana Figueres.

Ariana Brocious: She was basically the architect of the Paris Agreement. So, big deal. This is also the third year in a row that the climate conference has been held in a country with a history of cracking down on the press and peaceful protesters.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, I’ve been to several COPs and I could really see the difference.I remember in Paris and other democratic countries – outside the main venue, there were a hundred thousand people campaigning… some were protesting, some were handing out leaflets, but it was a really vibrant scene. But in Egypt, the presence of civil society was largely absent. Areas designated for the public were limited and hard to get to. And on some stretches of the road, there were more armed guards than members of the public. It was stark and intimidating.

Ariana Brocious: And I can’t help but feel that, with Donald Trump’s re-election, we are also in danger of seeing future protests here in the US muted by our own government.

Greg Dalton: True. Already we’ve seen states like Tennessee, Arkansas, and Iowa pass laws aimed at criminalizing protests. And the current Congress is advancing a bill — known as HR 9495 — that would allow the Secretary of Treasury to revoke the nonprofit status of organizations deemed to support terrorism. In some cases, we’ve seen peaceful protestors at fossil fuel sites labeled as terrorists.

Ariana Brocious: Despite that trend, there are people all over the world putting their lives and livelihoods on the line for climate.

Greg Dalton: And that’s our focus today: heroic climate defenders. Far from comfortable UN negotiating halls, people all over the world are risking everything with their voices and their bodies. These protests usually start with local people defending their homes, their food and their water. But however small they may seem at the outset, the actions they take are supporting the web of life that affects us all and the air we breathe.

Ariana Brocious: I have such huge respect — and awe — for each of the people we talked with for this episode. I’m not sure I’m brave enough to do what any of them do. First up is Alfred Brownell – he’s president of Global Climate Legal Defense. He was born in a small village in rural Liberia, and went on to get his law degree in the United States. Then he returned home to help write the country's environmental laws. But advocating for the enforcement of those laws soon became dangerous.

[music change]

Ariana Brocious: In the early 2000s, the Liberian government began leasing forest land to foreign companies to cut down the forests and replace with palm oil plantations. These tropical forests were not far from where Alfred had grown up.

Alfred Brownell: This was in the heart of the Liberian tropical forest. It was near the prime protected areas called Sappo National Park.

Ariana Brocious: So he went with some community members to see for himself what was happening.

Alfred Brownell: The destruction was unbelievable what we saw. Let me just say. The huge amount of timber that were being destroyed, the rivers, I mean,, the burial grounds, the traditional areas, the impact on the communities, the impact on food security, just the brutality of local officials against the communities was despicable.

Ariana Brocious: Alfred knew that the palm oil company had signed a commitment to uphold the standards of an international trade group called the Round Table on Sustainable Palm Oil. Members of this group promise zero deforestation and no harm to local communities.. But after seeing all that destruction, Alfred filed a complaint with the Round Table. The group took the complaint seriously and ordered the company in Liberia to halt operations. That would have put the company in a tough financial spot. So instead of halting operations, they expanded them.

Alfred Brownell: They had promised the investors. They had promised the bank they could, you know, clear cut millions and millions of acres of land. pristine forest land and transform that forest into oil palm and these guys would just make a lot of money. And they did not expect that there will have been any resistance and issues from Liberians,

Ariana Brocious: On that front, they were wrong. Alfred's organization kept documenting abuses. In response, the company turned to the Liberian government to put pressure on Alfred.

Alfred Brownell: I was particularly identified as the problem – that I was inciting the communities, that I was stopping investment. My very citizenship was being challenged. You know that, I was anti-country, I was anti-investment, I was anti-development, um, that I was a saboteur, um, and all kinds of threats.

Ariana Brocious: Alfred says his own government put him under surveillance, broke into his bank account, accused him of money laundering.... But Alfred wasn’t intimidated. He got representatives of the palm oil industry group to come to Liberia to see for themselves the company was defying their orders to halt operations.

Alfred Brownell: We took them to see what the expansion was. In fact, they were constructing an oil palm mill in a place called Pala Hill. And Pala Hill was like a sacred area to the traditional Blago people in Tajuan. This was an area where they make pilgrimage every year to go and worship their gods in the mountains. And on the very site where these people were worship, they were tearing down this temple. They were breaking it down. And you could see the crying and the wailings and the tears of the people who had accompanied us to witness. They could not believe that destruction that was occurring in that place. As the company tore down their sacred site, the things that their ancestors, their forebears had worshipped, what they had planned to pass on to their children and children, children. All of that was being destroyed in their eyes.

Ariana Brocious: After witnessing this destruction, the monitors left. Alfred and his team stayed behind to talk with the locals whose temple had just been destroyed. And that's when things got really bad…

A heads up: Alfred’s account of what came next is harrowing and graphic, and may be upsetting to some listeners.

Alfred Brownell: When we got into a vehicle to come back, we were ambushed along the road. the company private militias and securities and some of their employees. set up a massive roadblock. And when we arrived at the roadblock, they were looking for us. They said, we need to find Mr. Brownell, the lawyer. Where's the lawyer? Where's the lawyer? Where's Mr. Brownell? They're looking for me. You know, um, even though I was sitting in the front seat, I had a t shirt, I had on a jean trouser, I had on a, you know, a flip flop. So you will not know who the lawyer is, right?

Ariana Brocious: But eventually, someone identified him.

Alfred Brownell: And then all these people came around, they surrounded the vehicle. Uh, there was about a hundred plus of them They had, machetes, Some of them had guns in their hand, and they started to sing. They started to rub chalk over their faces. They started war dances around the car. Um, they started to t me and my colleagues, um, they threaten me. They were going to, you know, and they said it was gonna take off my heart. The guy said, my boss is waiting for your heart. He's going to eat it. The other guy said, my boss is going to use your skull to drink his wine from it. And they danced around the car and then they lit their bonfire as they danced and they sang. And then they were sharing, you know, um, alcohol. They was drinking. And it was terrible as I sat in the car and, uh, you know, even colleagues who were in the car and had almost like given up as they look around and, you know, I look across and people were sweating, were sitting in that car, I don't know how many hours it was, but maybe three or four hours then they lit their bonfire, they put a pot on the fire and said, we're going to cook you. You know, they pointed to the fire, it was blazing And then they said, okay, it's time now. And then they went for the chief. Because in the tradition was that the chief would come in and, and get me out. Then they would take me to the slaughter and cannibalize me. So they had everything set up, you know, the table, they are going to, uh, to, to, to slaughter me. It was all set up. They were ready for that. They pour herbs in the pot. And so I'll sat down and watch the fire being built to cook me, the pot, you know, they put on the fire that I was going to be cooked into, I saw it, I could see the steam coming from out of it, and I just told myself, You know, I'm a Christian, so I say, well, Lord, if this is it, that's it. If I'm doing something that is wrong, then I am ready to face that. And I look up into the air, into the sky, I look at the sun, I look at the breeze, And all of a sudden, you know, I feel like free. And then the chief started coming to the vehicle and the chief said, hello. I said, hello. He said, are you Mr. Brownell? I said, yes, I'm Mr. Brownell. And he said, he turned around and he said, He said, these people want to kill you, but I'm the chief in this town, and I cannot allow them to kill you in this town. He said, I cannot allow your blood to touch this land. There will be a curse on this land. So if they want to kill you, I'm asking them to take you to another town to kill you, but not in this town. And then a young man by the queue said, But That's not what we agreed on. We agree. We're going to take him down and kill him and eat him.Then he hit the chief on his side. Then another young man said, oh, but why are you insulting our chief? Why are you talking to him like that?

And then the conflict started among the young people. So the chief gives the order to the other young person, go ahead and move the roadblock. That's not going to happen here. And so everyone rushed to the roadblock. It's like to fight over the logs that they have put in and luckily they move enough of the logs that will allow us to go. Then I told my driver, I said, let's go. We rushed through the left few logs and the vehicles roll over them. .

[music beat/transition]

Ariana Brocious: Alfred escaped to another community — a place where he had done work. Friends and colleagues there kept him safe for a week before helping him get back home.

Alfred Brownell: My wife and kids were in the kitchen and I broke down. I didn't know what happened. The moment I saw my kids and my wife in the kitchen, I just started to cry. My wife said, what's happened? I couldn't explain. I just dropped on the floor because I didn't, I never believed in my mind that I was going to come out of that process in life that day. And I could not believe that I was seeing my kids, I thought it was almost like a dream and the magic that I could walk and see my kids with their mom in the kitchen and you know, but I took that on and I kept working and I kept resisting and I kept organizing and I kept, you know, representing communities and we refused to give up the case

Ariana Brocious: Still, Alfred's ordeal wasn't over. He had defied the company, and he had defied the government backing the company. Soon enough, a judge ordered his arrest.

Alfred Brownell: They went and got, uh, gangsters from the nearby ghetto. Uh, to come and, uh, attack my office. Fortunately, that day, I was not at my office, I had gone to a funeral. And they attacked my office, they attacked my colleagues, They were threatening that that was going to be my end, they were going to kill me.

Ariana Brocious: His colleagues urged him to flee. So did his contacts abroad. They said that they appreciated the work he was doing but that he would be of no use if he were dead. An American friend came down on him particularly hard for putting his family in danger..

Alfred Brownell: She said, you are endangering your wife and kids. How can you talk about protecting the Earth and the planet when you can't even protect your wife and kids who are currently under threat because of your actions?

Ariana Brocious: Alfred Brownell moved with his family to Boston. He is now teaching human rights at Georgetown Law in Washington, DC. His ordeal prompted him to found Global Climate Legal Defense in order to provide legal support to people protesting environmental injustice – even other lawyers like himself. As more environmental and human rights attorneys are hit with criminal lawsuits, defamation suits, even tax charges, they may not have the specific expertise to defend themselves. His organization provides that defense to activists around the world.

Alfred Brownell: We have to protect and secure those who are at the front line. We have to protect the climate movement. We have to protect indigenous communities. We have to protect the activists who are taking the ultimate risks. We have to ensure that defenders will continue to engage and dismantle this fossil fuel infrastructure that is contributing to global warming across the globe.

[music change]

Greg Dalton: Wow. That is just chilling, that image of him being surrounded.

One final note: Alfred says that after escaping the ambush and returning to the capital, he reported the incident to the government. He says there was no investigation. And as we'll hear from our next guest, impunity for perpetrators of this kind of violence is the norm.

Greg Dalton: Laura Furones is Senior Advisor to the Land and Environmental Defenders Campaign at Global Witness, an organization that investigates the links between resource extraction, corruption, and violence. According to Global Witness, more than 2,100 land and environmental defenders were killed worldwide in the last decade. That’s more than three people a week, on average. And that’s only the deaths that are reported. I asked Laura Furones what drives that level of violence.

Laura Furones: A lot of cases where we've seen communities that are trying to protect their lands and their environment from corporate interests, you know, whether it's mining interest or logging interest, um, big, um, agribusiness, um, companies that are trying to come into the lands and extract their resources and often doing so without even consulting the communities living. In those lands. And so, uh, the communities are kind of forced to take a stand against those interests that are about to destroy the livelihoods, the, their environment, you know, the, the quality of life, the future. Um, and it's there that we very often see in that clash, the communities are attacked. And sadly, sometimes defenders are murdered as a result.

Greg Dalton: I’m guessing those murders don't tell the whole story, you know, these are very remote places. What can you say about under reporting?

Laura Furones: No, they really don't. Uh, murders are really striking. They're the most extreme form of violence, for sure. But it's also really common to see other types of non lethal attacks. such as threats and harassment, intimidation, sexual violence. Criminalization is, you know, another example, uh, that's on the rise globally. And that's where the very legal system that's meant to protect offenders turns against them. And we've seen that everywhere,the other thing, um, that I think it's important to note here is that it's really hard to document the cases that do occur, you know, accessing information is an ongoing challenge and the result of a very complex mixture of compromised civic space, lack of freedom of press and just the reticence to report cases for fear of reprisals as well.

Greg Dalton: So what consequences do the perpetrators of violence generally face?

Laura Furones: Well, the truth is that, um, typically, uh, the large majority of cases result in no consequences at all. I think if there's a word that really defines the defender space, it's impunity. If we are lucky, we might see a hitman, the person who pulls the trigger, but those are generally hired assassins and it's them who sometimes might end up in jail, but the people behind it, the intellectual perpetrators, the people who thought about the, who wanted for the murder to happen, who paid for the murder, you know, who organized the whole thing are very, very rarely jailed or even tried.

Greg Dalton: So could you walk us through a specific case that illustrates the dangers defenders face? Of all the people that you've encountered on the front lines, whose story has moved you the most?

Laura Furones: I think it's still one of my earliest experiences that remains one of the most vivid as well. And I think it's, it's a good illustration of the reality that Defenders, uh, face. Um, and it was, uh, accompanying, uh, a priest in Honduras, Father Andres Tamayo. Um, Father Tamayo was, uh, leading, um, the peaceful fight against illegal logging in the region where he lived. Um, illegal logging was an activity that was destroying forests, but it was also, you know, throwing people further into poverty. It was having really severe environmental and social impacts. And he was constantly threatened for the work that he did, as so many other defenders are. And so I remember very clearly a colleague of mine, uh, and I were with him in his church, um, in his little village of Salama one night. Um, when he got a call warning him that his, um, life was in imminent danger and that he should stay indoors, he should just stay safe. Um, you know, the moment he heard that he put his shoes on and went out for a walk, I think he wanted everyone to see that he would not be intimidated, nor would he stop doing his work and, you know, walking by his side as he went through the dark streets, you know, the tension was really palpable. You know, some, some people would come and greet him and thank him for his work. But some people, some men in particular, would look at him in a very threatening, uh, way holding, you know, onto the guns in the holsters. And luckily nothing happened, but it was so clear that a lot could have happened. The whole point here is that this is the reality many defenders face. They live under constant threat. the risk in their lives every single day for the work they do. And they never know when they're going to encounter the day where someone will actually shoot them.

Greg Dalton: There’s also the story of two young activists in the Philippines, who were working to stop a massive airport construction project that would have destroyed their livelihoods. Can you share that story?

Laura Furones: Yes, absolutely. Jed and Janila are two young female activists who are known for opposing a huge, land reclamation project in Manila Bay. What it meant in practice was, um, you know, displacement of hundreds of families, destroyed, uh, climate critical habitats, uh, devastated wildlife. It had huge, uh, social and environmental impact. So Jed and Janela were abducted for 17 days by their own government last year. They were eventually released. And they were released on the condition that they would quote, unquote, confess, to being communist rebels, which of course they were not. Um, so the government organized a press conference nd they were given a script.

Greg Dalton: So I'm just getting a picture in my mind of like, a bunch of military people, press conference, media there. They walk in, they've been incarcerated for 17 days and, and what happens?

Laura Furones: And then what happens is the most extraordinary thing possible, which is that they, they told the truth. They, they told everyone who was there about their abduction and they told everyone who about, about what they had suffered, uh, throughout those 17 days that they were abducted and who their abductors were, uh, you know, um, and everyone, the, the, everyone from the press in the Philippines, but also beyond was there to take notes. So you can imagine the level of risk that they were taking by doing this. They were literally surrounded by armed forces in the Philippines who could have just killed them right there or maybe the following day. You know, the risk they were taking was absolutely tremendous.

Greg Dalton: And what's happened to them? Where are they today?

Laura Furones: Today both Jed and Janela are alive, which is, which is the most important thing to say. And they're actually both still working as activists. This is what's incredible about these stories is that. Nothing stops them, as they say themselves, they could just take an easy job, uh, you know, take a, have a quiet life, but they won't do that. They will continue to do their work despite still being under constant threat.

Greg Dalton: We’ll hear more from Laura Furones later in the show. We’re going to take a quick break.

Coming up, we’ll talk with an activist in Brazil. She stood up to offshore gas and they fired back – with intimidation, lawsuits, and maybe even a jail sentence. But she says she won’t back down.

Nicole Figueiredo de Oliveira: I know this is the risk. I know it kind of comes with the activity I do. So it's the fact that I'm in risk of going to prison. I'm in peace with that.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Ariana Brocious: We’re always trying to get people talking about climate. You can help others find our show by leaving us a review or rating. Thanks for your support!

Ariana Brocious: This is Climate One. I’m Ariana Brocious. Today we’re talking with some of the boldest activists working in climate: people who are putting their lives on the line to defend their environment.

In 2020, Brazil granted the Turkish company Karpowership permission to bring in four off-shore, gas-fired power plants without the usual environmental review. When these massive, floating power plants started showing up in the Sepetiba [seh-puh-CHEE-buh] Bay, local fishermen were concerned.

Nicole Figueiredo de Oliveira: So fishers saw this strange ship parked on the bay of Angra and they didn't know what it was and they found it very strange because, of course, it's a floating power plant with chimneys and turbines, so it's very strange for somebody who doesn't is not used to it. And in Brazil, we never saw this before.

Ariana Brocious: That’s Nicole Figueiredo de Oliveira. She’s a lawyer and the Executive Director of Arayara, a Brazilian non-profit with the mission of stopping fossil fuel expansion in Latin America. She says the power plants were blocking the local fishermen's access to the fish and disrupting the spawning area in the mangroves. But standing up to the company was complicated.

Nicole Figueiredo de Oliveira: The fishers, the boat operators, and everyone who was kind of providing services to Karpowership was depending on the services that they were contracting. So, you know, taking people on and off shore, uh, bringing food, transporting. And, um, of course, they were afraid of, uh, losing the contracts. And at the same time, it was really intimidating because they were giant boats that were placed exactly where the fishes were. So since they were placed in front of the mangrove, to pass the transmission line to the continent. The mangrove is the place where the fishes reproduce, they eat and they live. And when these ships were installed, it created an exclusion zone, which means fishers could not reach the area of the ship. And then fishers were prevented from reaching the area. the area. And when they went, they got fined by the Navy. So it was very intimidating for the people, uh, locally to do something. So that's why we got involved so heavily.

Ariana Brocious: Nicole looked for support through the legal system. Her organization got a court order suspending the company’s operations in the bay. And then she took it a step further…

Nicole Figueiredo de Oliveira: I waited for them until they were officially notified of the sentence. Um, and then I went with two women from my team. And the idea was to see if they really suspended the project after the court order. So we took a boat and I went there with the sentence in my hand and I delivered to the responsible person saying that there is a court order and I asked them if they knew about it. They said no. So I gave them the court order and I said, okay, now you know, so now you have to suspend it.

Ariana Brocious: And that’s when Nicole became a target herself. She had used the law to try to stop the company. And then the company turned around and sued her. I asked her what the grounds were for that suit.

Nicole Figueiredo de Oliveira: It was a defamation suit, basically. They had other crimes that they said I did. One of them is, uh, for allegedly saying that they, uh, killed gray dolphins. And gray dolphins are this very sensitive, threatened to extinction species of dolphins that have very few individuals in the Guanabara Bay and Cepechiba Bay. The Cepechiba Bay is where these power plants are being installed. So, uh, we did a campaign called SOS, uh, Gray Dolphin. And in Portuguese was SOS Botucinza, which means SOS Gray Dolphin. Uh, and in the translation to English, unfortunately, uh, a mistake was made and somebody translated to stop killing the dolphins. And I retweeted that. So one of the things they are saying is that I'm accusing them of killing gray dolphins. And actually the whole purpose of the campaign was just to call attention that a project like this, because of the noise, because of the temperature of the water, they They use, uh, to cool the turbines and put back on the water and, uh, all the other impacts that this has on the bay, that this threatens gray dolphins that are already super endangered.

The second one was, they said that I couldn't have said that they committed a crime because the only one who can say they committed a crime is the court and a disobeying of a court order is a crime. So that's what I said and I said this while the court order was valid. I went online, we did streaming, I gave interviews, I went, uh, different places saying that they were committing the crime of, uh, court order disobeying. And they said that I wasn't allowed to say that.

Ariana Brocious: What's the status now of that lawsuit against you?

Nicole Figueiredo de Oliveira: So I have two. Um, uh, after this one came, I gave an, uh, interview to another podcast from South Africa, from an organization called Alta. And, um, I said that they were intimidating fishers. and they committed a crime, uh, for disobeying a court order. So then I got the second lawsuit. And in the hearing, the, their lawyer asked me, don't you think it's a disrespect to the court? Even after you had the first lawsuit, you continue to give interviews about the issue. So it was clearly an attempt to silence me. And then when it was my turn to testify, it was really empowering because I could say, yes, I said that with no intention to defame anyone. My intention was just to protect the bay, the environment, climate, and the communities that live there, fishers and everyone else. So, I stand for what I said. They did disobey a court order while the order was valid. So it was kind of empowering to reinforce what I said, even though I'm risking a lot in this lawsuit, the two lawsuits, all together, I could get up to three years of prison time if I am found guilty, I have no idea what's going to happen, even thoughI am, you know, in the, um, uh, I don't know if there's a right side of the story, but, you know, I feel I'm in the right side, um, and

Ariana Brocious: You don't know the outcome.

Nicole Figueiredo de Oliveira: no, my sentence will supposedly will come before the end of the year and I will know.

Ariana Brocious: Okay. Wow. Um, so what has it been like to experience this? I mean, what, what has been the impact of the stress of these lawsuits on you?

Nicole Figueiredo de Oliveira: Yeah, so, you know, the first thing, it's, it's horrible what I'm gonna say, but the first thing I thought when I got the, the notification of the lawsuit is I'm glad my mom is not, no longer alive, so she doesn't see her daughter going through this, because I've, for me, honesty has always been a value and a most important one for me.So, um, being accused of being a criminal is a big burden for me. Emotionally. Um, so the possibility of going to prison was very stressful. Last year, I got pregnant of Annabella, who was my daughter. And when I was, uh, six months pregnant, uh, Annabella died.

Ariana Brocious: Oh my…

Nicole Figueiredo de Oliveira: And I think it's because of the stress I went through and thinking of, uh, what, what's gonna happen if I go to prison with Annabella? And can I go to prison with her? And is she gonna be born in prison? You know, there's like a bunch of questions that I can't, you know, you can't stop asking yourself when you're in this situation. So this was, terrible. Um, not knowing the outcome of the lawsuit is another big burden because it's taking so long. So it started in 22, I think, and now, you know, we are ending 24 and still don't have a decision. Um, but at the same time, You know, I don't deal well with being intimidated. I'm, I'm an activist. I have been all my life. I, I fight big corporations and I fight fossil fuels and it's, it's something that I chose to do. I think it's kind of like my, my mission on the earth. the fact that I'm in risk of going to prison. I'm in peace with that, despite all the stress, but being intimidated, I don't deal well with that. I don't like to have someone telling me to be silent, um, especially when there's so many people who cannot speak already. And during the whole lawsuit, I had to leave out the important evidence that proved my points, because I would have to, uh, name the people that were giving me the data and were contacting me and were telling me the information, and I'm not going to do that. So I would rather be found guilty than delivering names and, you know, uh, putting people exposed like that. So this is one thing. The other thing is

Ariana Brocious: That is a lot. Just that is a lot.

Nicole Figueiredo de Oliveira: Yeah, it's a lot.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah.

Nicole Figueiredo de Oliveira: Yeah, yeah, it's a lot. Sorry, I didn't breathe because it's kind of also making me anxious and I know some people might feel triggered by hearing that but yeah, that's a lot. Yeah. So the other thing that happened was, um, in this process, we found a coalition of other organizations that have been also being threatened by Karpowership for, uh, some kind of defamation lawsuit or who are, uh, trying to stop their projects in their countries. And there's organizations from Africa, from the Caribbean, from Latin America. So it has been a great process to also get to know, uh, people that are really brave and, um, smart lawyers. And we have been, you know, kind of supporting each other also as a community. And it has been the positive side of the whole story.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah. And I am impressed that you can hold both those things at the same time.

Ariana Brocious: So, you're, you work with many climate defenders, you are one yourself, and I think for some people when we use that phrase, they might picture somebody on the front line laying down in front of an oil rig or a bulldozer or something. When you hear the words climate defender, who do you picture?

Nicole Figueiredo de Oliveira: it's interesting, you know, once I took this indigenous person to the COP and he was like, I don't like being called a defender because I'm in my territory, I'm defending it because I have to, it's not that I chose to be here or to do this, So there's this kind of, uh, defenders that are people in the territory that are, don't choose. to be a defender and they are placed in a position like that. There's also people like me who choose to be a defender and defend the environment and planet and There is, um, state attorneys and whistleblowers inside companies, you know, oil workers who, uh, whistle blow about a blowout or a leak or a mismanagement of a platform who are also being persecuted, lose their jobs. so a defender doesn't really have a specific face, uh, or a specific role, but, um, it's a person or a group of people who, when the time, when the time comes, they stand up for what they think is necessary and they put themselves at risk and sometimes their families and their whole livelihoods to defend, you know, to do what they think is necessary and right.

Ariana Brocious: Mm hmm. So presumably the goal of intimidation, harassment, legal threats, physical threats is to scare people away from the work that you and others do in defending your homes, your climate, the environment. What would it take to actually get you to stop doing the work you do?

Nicole Figueiredo de Oliveira: Nothing. I will not stop. Only if I, of course, if I'm killed, I would stop. But I don't think the people that are around me would. This would actually only fuel, for, more, eagerness to continue fighting. Um, and that's what happens with me in this situation. Uh, lawsuit, you know, they want to silence me, but they, I think they didn't know that I don't deal well with being silenced. And I, this will not make me be quiet and actually giving this interview right now, I am risking to get another lawsuit and having to go through the whole process again. But I think people should know what's happening and what they're doing. We don't really know the impact that we have in the long run, uh, for the work we do, but I do know that it's a cascade, escalation of events that will help a lot of people. Uh, so I will continue doing what I do forever until I die.

Ariana Brocious: Thank you for taking an additional risk and talking with us. Nicole Figueiredo de Oliveira is Executive Director of Arayara, thank you again for joining us on Climate One.

Nicole Figueiredo de Oliveira: Thank you for having me.

Greg Dalton: As of this taping, the lawsuit is still pending. In an online statement, Karpowership, the company operating the natural gas plants on ships, says it provides training to fishing communities and residents and also does reforestation in degraded areas.

We’re going to take another quick break. When we come back, a doctor based in the UK realizes she’s navigating two crises at once.

Sarah Benn: The climate emergency is a health emergency. Not just in the global South, but all over the world.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton.

The consequences of burning fossil fuels are vast. But one that doesn’t get enough airtime is the impact on our health: respiratory disease, as well as deaths from flooding and extreme heat, and tropical diseases are all on the rise. The health of humanity and our planet are inextricably linked.

Sarah Benn: If the planet were my patient, I would be about as concerned as I could be.

Greg Dalton: Sarah Benn is a General Practitioner in the UK. In 2022 she participated in a sit-in in front of the Kingsbury oil terminal. She was arrested alongside fellow activists and prosecuted. Dr. Benn ultimately lost her medical license and was sentenced to 32 days in prison…

Sarah Benn: I had sort of mentally prepared myself for it in some ways, but even so, it felt very kind of final. There was no, going back from there. And when I was finally me and my cellmate eventually in our cell together and the door closed and then that was it. That was my little patch for 23 and a bit hours a day. That was, uh, quite a shocking moment. Um, because although I'd pictured it in my head, you know, the reality is somewhat different as the hours stretch ahead.

Greg Dalton: And how did serving that jail time impact you?

Sarah Benn: it really made me appreciate the simple things that I thought I appreciated, but I really didn't. Like the ability to just walk out my front door and, into the fresh air, go in the garden, uh, walk in a straight line for more than sort of 25 meters. Choose what I wanted for dinner, what I wanted to, you know, if I wanted to watch a movie or buy something to eat or all those simple little things, or even just, um, speak to somebody that I knew. All those are kind of gone. I really, really appreciated them when I came out and I hope that I continue, you know, I keep reminding myself of how, how valuable those things are and how easily they can be sort of snatched away.

Greg Dalton: Yeah. The little micro freedoms we take for granted. That incident that led to your imprisonment wasn't the first time you've been arrested, in 2019, you also were arrested for flying drones near Heathrow international airport. I remember reading about that in the news and saying, yeesh, what were you trying to achieve in that case?

Sarah Benn: Well, for a start, I mean, yes, it sounds horrific. Um, I was flying a plastic toy drone bought from Argos, which weighed 42 grams and was tied to the ground because I was such an incompetent drone pilot. The idea was to stop them flying at Heathrow, uh, for 24 hours by telling the airport authorities that we would be flying drones in the area. And they're supposed to then shut down flying. In the end they didn't because the action was so safe. Um, we were flying well away from flight paths. Um, I was in a wood. Um, and as I say, my, my drone was tethered to the ground because I was such a useless pilot. I flew it into my head a few times and, uh, sustained no grievous injury. But it was all about trying to, uh, oppose the extra runway, um, planned for Heathrow airport.

Greg Dalton: Mm hmm. and you told them in advance. You know, it's interesting that your actions have been focused on both the supply of fossil fuels blocking the road to Kingsbury oil terminal and the demand side trying to stop expansion of a runway that would have, you know, cause more flights and use of jet fuels. What kind of climate actions do you think are most effective on the demand side or the supply side?

Sarah Benn: I think we've got to do it all. The stopping burning fossil fuels really is a, a no brainer. Um, it's turning off the tap at source rather than trying to deal with the water overflowing the sides of the bathtub. We cannot stay within climate targets. If we, uh, burn, if we dig up any more fossil fuels, there's enough to take us over the limits if we just burn what's already been, um, dug up, so that that has to happen, that is a complete no brainer. Um, but yes, on the demand side, I think, you know, we, we have to understand that we can't keep living the lives that we've, or at least some of us have got used to. Um, which are really destroying our livable planet and flying is quite a big one.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, that's a, that's right. The story that put you in international spotlight was not your arrest per se, but the fact that following your prison sentence, you were brought before a medical practitioner's tribunal, which suspended your designation as a registered doctor in the UK. There's a lot to unpack there, but let's start with what connections do you see between climate change and public health?

Sarah Benn: Well, the climate emergency is a health emergency, not just in the global South, but all over the world. Climate change is having devastating impacts on, uh, our ability to grow food, to feed ourselves. And again, this hasn't hit us so much in, uh, in Europe, um, but, you've only got to look at the pictures on the TV of areas where crops have failed, where they've had drought year on year, on year because of climate change or the opposite, you know, terrible flooding where crops have have rotted in the fields. Our ability to to grow food is going to be impacted. Rising heat causes heat deaths. There were 3000 excess deaths in the UK in 2022 when we saw temperatures over 40 degrees. We have the spread of, uh, vector borne diseases like, um, malaria and dengue fever, schistosomiasis, all expanding their range because of temperatures getting warmer. Also, what really concerns me is the possibility of kind of societal breakdown, um, because of conflict over resources. Uh, we see this with armed conflict breaking out in different areas of the world. There can be no sort of health in a, country where things, society is breaking down, you know, the infrastructure, functioning hospitals, functioning health services, and all the other things like, education, law and order break down when there is not enough to eat, not enough safe water to drink and no safe place to shelter. It absolutely is a health emergency and also air pollution, which goes along with the burning of fossil fuels that kills a huge number of people every year.

Greg Dalton: Right. Though the tribunal, which is sort of a medical court in the UK, uh, saw it differently. They said your actions brought the medical profession into disrepute. What do you think they were really worried about? You know, how does a, you know, near retirement doctor sitting down and getting arrested on a road, you know, threaten the medical reputation in the UK?

Sarah Benn: Well, that's a very good question. I think it was very lazy thinking on their part. I don't think they made any kind of effort to understand my motivations and give any kind of thought as to how they might deal with it differently. When doctors break the law and I, I didn't do it lightly. There's no other reason that I would have done it. When doctors break the law, yes, it can affect public trust. But when I looked at the reasons that other doctors had been suspended or erased from the register, they all involved some aspect of personal gain, um, whether that be financial or through inappropriate relationships, exploitation of patients, or, or sometimes for, you know, make people with odd theories, making a name for themselves, this kind of thing. Very different from my situation. I got no personal gain out of it whatsoever. And in fact, quite, quite the opposite. I think these are exceptional circumstances that we find ourselves in. And the GMC could have chosen to just take a beat and think about it a bit and choose instead to not take action against me given that I'm no risk to patients, no longer practicing, and my clinical career was unblemished when I was practicing. So given that, they could have explained to the public why they were not taking action against somebody who was actually standing up for life and health, public health, in this country and all over the world. Why they chose not to take action. Um, they could have done that, but, um, they didn't.

Greg Dalton: And a sympathetic article in the British medical journal says that your case sends an unwelcome deterrent to other climate concerned doctors. Are you seeing a chilling effect? What do you hear about the impact of your case?

Sarah Benn: I think other doctors are understandably very concerned, um, as to what might be, um, the effect on their own career, um, for taking action. But there are a good number of fellow doctors who have taken action. And to put it into perspective, I started, um, uh, being involved in climate activism, which had brought me into conflict with the law back in 2019. And it's taken a long, long time to kind of get to this point where they recommended suspension. There are plenty of doctors who've taken action at a sort of lesser level who've been arrested, who've, who've been charged with offenses, um, where it hasn't impacted their career yet. The fear I have, though, is that, you know, the penalties are becoming more harsh, more severe through the courts and the General Medical Council really rely on the court's assessment of seriousness, if you like. They felt that having a doctor going to prison, no matter what the reason, the public would not understand why. They would simply see a doctor going to prison. And if they took no action, then it would mean all doctors were potentially untrustworthy.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, they don't want doctors to be seen as criminals, right? Yeah. You know, from your white coat to a prison suit, sort of jumpsuit sort of thing. We hear this a lot of other professionals in other fields, scientists are told to, you know, not get engaged in civil disobedience because the public will not trust their science. They'll think that their science is politically tainted or motivated, you know, how do you react to that? Other professionals?

Sarah Benn: I mean, this is not politics. It's about survival and, you know, we're generally, uh, quite a kind of conforming, um, conservative with a small C group of people. We, we have to be to get to that position. But this, the climate emergency, as I said, being a real health emergency and an existential threat to human existence, um, I think the public see people who are driven to desperation. I mean, I, I talk to scientists and they are all so very frightened of what is unfolding. And again, they tend to be very conservative in, in what they say. They don't want to get it wrong. They don't want to over egg things. And I think they, they're becoming aware of how, you know, that's been a real problem because um, people have not, have not, wanted to scare the public, if you like,

Greg Dalton: right,

Sarah Benn: But we need to be scared because there's really bad stuff unfolding.

Greg Dalton: you know, people, some people, you know, our age will remember Helen, Helen Caldecott, who started, you know, movement became physicians for social responsibility. They came out of the existential threat of, uh, nuclear weapons in the cold war. So that's not the first time that doctors have used their moral voice and trust in society, and you're retired now, as I understand it. You were about to retire when you first started taking climate action. Would you have been as willing to put your career on the line, um, If you had been earlier in your career?

Sarah Benn: To be honest, I would probably have thought about it, um, a bit more in depth, a bit longer and taken a while longer to jump in. When I started in 2019, um, I was actually, uh, working and intending to continue. I, I didn't sort of decide to, uh, to leave clinical practice until 2022. So I was still practicing. I was, however, in the fortunate position of having, you know, paid off my mortgage and mostly got my kids sort of to a, a decent kind of age. So that made life easier. Realistically. Yeah. If I'd been kind of, 30 or a little bit older with my children, still small. Yeah, I, I, I might've been more reticent to do it, but, but I think still, Yeah, it's because of them. You know, that really drives me on. It's because of my children and their future and my fears for them that I, I just, I don't really feel I have a choice about it. It's just something that's got to be done. And if, if, if I don't do it, who will?

Greg Dalton: Well, Dr. Benn, if I were ill in the UK, I would trust you to care for me and think you're of good character. So thank you so much for sharing your moral, courageous story with us.

Sarah Benn: Thank you for, for hearing me.

Greg Dalton: Sarah Benn is a Doctor and Climate Activist based in Birmingham, England.

I want to return to my conversation with Laura Furones. She works at Global Witness, the organization that investigates the links between resource extraction, corruption, and violence. After hearing all of these moving first-hand accounts, I wanted to know what can be done to address the root cause of these attacks on climate defenders. There are bright spots in this story.

Laura Furones: One of the reasons violence continues is that there's that nothing's stopping companies and, you know, other interests from, from harming defenders, I think the good news there is that there is a number of pieces of legislation that are in place and we need to prove their worth. You know, there's a very recent, um, piece of legislation in the EU, a directive that's called a corporate and due diligence directive. And what this does is that it makes it compulsory for, um, companies to have to identify risks and assess risks and minimize risks, but also, and I think this is really crucial, it gives communities and defenders the right to submit complaints and sue companies in EU courts if companies cause harm, uh, to, to them, you know, or to the environment. So all these mechanisms that are in place need to be fully implemented.

Greg Dalton: So if there's some logging that happens in, uh, in, uh, Latin America or Africa that for furniture to go into Europe, those companies could be sued in Europe for that action in Africa or Latin America.

Laura Furones: Exactly. They could be sued and they would also be obliged to compensate those communities. You know, obviously what we'd like to see is for the harm not to be done in the first place.

Greg Dalton: Right. and there's a similar effort on, on deforestation to prove that, uh, supply chains don't contribute to the destruction of forests. This episode is publishing just as the UN wraps up its annual climate conference in Baku, Azerbaijan. Regardless of whatever new promises come out of this meeting and the expectations are low, what do you want people to know about the people on the ground – the front lines, defending their homes and livelihoods?

Laura Furones: Well, I think it's really important to remember that the defenders across the world are normally ordinary people doing an extraordinary, uh, job, you know, and doing, uh, doing something that is for the benefit of us all. They're not doing, uh, that, you know, they're not defenders just to protect their own resources and their own, um, you know, livelihoods. They're also doing work that belongs to all of us. That's going to benefit all of us, you know? So I think it's really important that we continue to defend them, that we continue to help them have their voices heard, not only as sort of voices on the sidelines, but those voices need to be central to that decision making around tackling the climate crisis.

Greg Dalton: Laura Furones, thank you so much for sharing the insight and the courage of these people protecting natural resources. I'm still having an image of those young people in the Philippines surrounded by military, um, soldiers saying. The bold truth. That's just amazing. Thank you, Laura.

Laura Furones: Thank you for having me.

Ariana Brocious: And that’s our show. Thanks for listening. Talking about climate can be hard, and exciting and interesting — and it’s critical to address the transitions we need to make in all parts of society. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. You can do it right now on your device. Or consider joining us on Patreon and supporting the show that way.

Greg Dalton: Climate One is a production of the Commonwealth Club led by Gloria Duffy. Our team includes Brad Marshland, Jenny Park, Ariana Brocious, Austin Colón, Megan Biscieglia, Ben Testani and Jenny Lawton. Our theme music is by George Young. I’m Greg Dalton.