Fighting Fossil Fuels All the Way to Prison

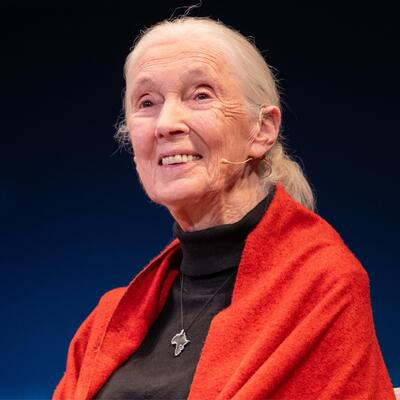

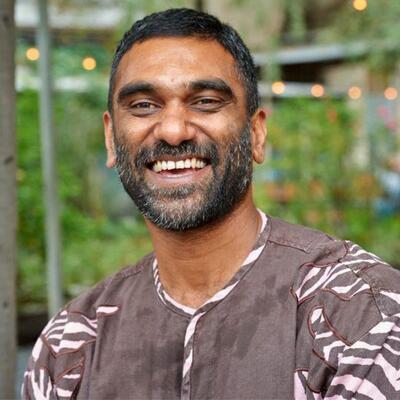

Guests

Tim DeChristopher

Georgia Hirsty

Brendon Steele

Summary

Radical protesters Tim DeChristopher and Georgia Hirsty put the “active” in “activism.” But is civil disobedience the best way to effect real change?

Full Transcript

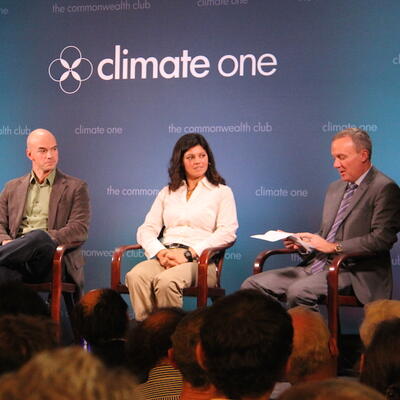

Greg Dalton: I'm Greg Dalton. And today, we’re talking with advocate seeking to influence companies and government to do more to combat climate change. Our guests applied pressure from outside and inside corporations from disrupting fossil fuel auctions and hanging off a bridge to privately collaborating with oil companies inside the halls of power. The goal is to create a faster transition from fossil fuels to clean energy. Over the next hour we’ll hear stories of fighting and partnering with fossil fuel companies and include questions from our live audience here at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco. We’re joined by three guests; Tim DeChristopher is the founder of the Climate Disobedience Center. He spent 21 months in federal prison for disrupting an auction for oil and gas leases near Canyonlands National Park in Utah. Georgia Hirsty is a National Warehouse Program Manager with Greenpeace. In 2015, she suspended herself off the St. John's Bridge in Portland in an attempt to block a Shell oil rig traveling to the Arctic. Brendon Steele is Director of Stakeholder Engagement with Future 500 a group that builds bridges between companies and their adversaries. Please welcome them to Climate One.

[Applause]

Tim DeChristopher, let's begin with you. You heard – you were a college student and you heard Terry Root give a talk about climate change and that changed your life, how?

Tim DeChristopher: Well, yeah I was studying climate change quite a bit at that point and had been an activist to some degree for a long time. But after her talk Terry sort of was honest with me in a way that she wasn't honest with the audience. She had presented the IPCC data up to that point and showed their scenarios for carbon emissions for the 21st century with the best case scenario peaking around 2030 and coming back down. And I went up to her afterwards and said “But didn’t the most recent report you guys put out, say that if emissions didn’t peak by around 2015 and start coming back down that we're pretty much all screwed.”

And she said “Yeah, that's right.” And I said, “What am I missing here? And she said, “You’re not missing anything.” There's no scenario on the table in which we avoid all the worst-case consequences that we’re looking at. And she literally put her hand on my shoulder and said “I'm sorry my generation failed yours.”

And so, it was incredibly rattling and did kind of push me into a dark period of despair, but it was also a period of grieving and letting go of a lot of what I was holding onto which also opened up a new kind of gratitude and deeper connection with the things that I loved about our world and the people that I loved that I was willing to fight for. And so it really motivated me to a new level of commitment and willingness to make sacrifices.

Greg Dalton: Let’s hear a video from that next chapter Tim DeChristopher went into next stage of activism. This is the trailer for a documentary about Tim DeChristopher’s life called “Bidder 70”

[Video Playback]

Tim DeChristopher: They said, “Hi, are you here for the auction?” and I said, “Yes, I am.” And they said, “Are you here to be a bidder?” and I said, “Well, yes I am.”

Auctioneer: Sold – to Bidder 70! Bidder 70!

Newscaster: An environmentalist threw a controversial oil and gas lease auction into turmoil today.

Newscaster: Tim DeChristopher says he’s willing to go to jail, and it’s possible that’s where he’ll wind up.

Newscaster: A college student faces federal criminal charges for disrupting that auction with bogus bids.

Newscaster: Actually winning a dozen bids in a row worth two million dollars.

[Applause]

Greg Dalton: Tim DeChristopher, take us to that moment. You go to that auction and you going in, what was your intent and what was your feeling at that moment where you’re walking up to that auction?

Tim DeChristopher: Well, my intent was to stand in the way of that auction in any way that I could. I’d been studying social movement history, and realizing that the climate movement at that time didn't really look anything like the successful social movements in our history because it was so focused on appeasing our current power structures and trying to make itself nonthreatening. And I saw that successful social movements have always pressured those in power and made them uncomfortable and using techniques like civil disobedience and things like that. So I was looking for the opportunity to do something like that and was going to a lot of stuff at that time and this turned out to be the perfect opportunity where they opened up the possibility for me to be a bidder and I couldn't really turn away from that. And it only took me about 20 minutes or half an hour so once I was sitting in the auction and saw all the opportunities that I had to make that decision. And I was just sort of looking at the situation, saying, if I do this I’ll probably go to prison for two or three years, could I live with that and I thought, yeah, I could live with that. But if I don't do this, and I pass up this opportunity and 30, 40 years down the road, you know, I'm meeting a young person who was born into a broken world and I knew that I had an opportunity to possibly do something about it and I didn't take it, could I live with that? And that's where eventually I had to say no, I really couldn't live with that and I've got to act here.

[Applause]

Greg Dalton: So you were prosecuted for a couple of federal crimes and then you went to prison. Did you convert any people to climate advocates when you are in prison?

Tim DeChristopher: You know, there was a guy in the bunk next to me that was a coal miner from Vernal, Utah and he only had one lung. So I think he already had some grievances against the coal industry. But I think I think I shifted his views a little bit about what kind of people stand up against the fossil fuel industry, you know, and a lot of the conversations that I had with folks in prison and in some of the prison activism that I did on the inside, wasn't really focus on climate change. It was focused on a lot of the issues that the people were dealing with in their lives either on the outside or on the inside working on addressing the prison health care system or the education system in there and that sort of thing.

Greg Dalton: Then you're out, now you’ve been out for a little bit, you're still on probation. Tell us about your reentry getting out and were you radicalized in prison or I guess you’re maybe radicalized before you went in.

Tim DeChristopher: Well, I’d tell you I was further radicalized in prison. I think it deepened a lot of my social justice perspectives and made real some things that I knew intellectually, you know. Like I'd read The New Jim Crow before I went into prison and that sort of thing. So I kind of like knew some of the facts, but it made those facts much more personal when I was spending two years with some of the most oppressed people in our society. So I think it deepened my understanding of that, it deepened my understanding of systemic evil. And I think that really radicalized me and made me more of a revolutionary. And so by the time I got out I was able to consider myself a prison abolitionist and could firmly stand by that position.

And once I understood that lens of how our current prison system is never going to become the kind of justice system that we need, and we need to build that justice system from scratch based on our values and our community resources, and our current prison system actually needs to be abolished. Once I understood that, that gave me a lens to then understand the struggle against fossil fuels where so many people say “Oh but we still need energy.” It helped me to see that the fossil fuel industry is never going to become the kind of clean energy system that we need. That we’re gonna have to build that system from scratch and the fossil fuel industry should be abolished. So it was actually my understanding of the struggle against mass incarceration in the prison system that help me to be able to stand by a position of saying that I'm a fossil fuel abolitionist.

Greg Dalton: And you're on probation, you weren’t able to go to Paris because of that. Can you envision getting arrested again?

Tim DeChristopher: Yeah, absolutely, very easily.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: Georgia Hirsty, you were in Los Angeles when Hurricane Katrina hit and what did you do?

Georgia Hirsty: I was working for KPFK which is a Pacifica Free-Speech radio station. And after watching the news and seen the kind of blatant racism that was coming across the airwaves, myself and two of my colleagues got in a vehicle and drove to New Orleans. And at the time they were only letting in media they weren't yet letting in volunteers. And so we spent the first week after the storm we got there three days after the storm, collecting stories from locals and spending the time with them and having them show us what they were going through and what they were dealing with and seeing the racism firsthand. And for me, at the time I'd been working I’d already been an activist particularly working with race, class and gender and mainstream politics. And the work that week and then I went back to New Orleans for about two years with volunteers and working with different groups down there, seeing really the kind of interplay between the climate justice movement and race, class and gender and how those things really are unable to be separated.

The other thing I learned in New Orleans was what direct action actually looked like and, you know, from people at the get go refusing to leave. Despite being told by the military and by police officers that they weren’t allowed to stay, people resisted. They stayed; they had camps on the roofs even though the seventh ward was still flooded, the ninth ward was flooded for almost a month afterward. And then that continued for years where people would stand, you know, toe to toe with bulldozers to protect the houses down there. So, it really kind of formed my understanding of direct action in the way that I, the narrative that I understand environmentalism from and environmental justice.

Greg Dalton: And you were then later also prosecuted for some federal crimes of involving oil.

Georgia Hirsty: Right. So in 2010, the BP spill happened which again devastated communities. So you see the interplay again between like what it's doing to our environment, what it's doing to the ocean. And then also just how it's ravaging communities and the places that are most affected by the – by climate change, and by environmental degradation are the places that tend to be people of color and lower income places. So you see very much that that connection exists.

So we did an action against the Harvey Explorer, which was contracted by Shell to go drill in the Arctic later that summer in 2010 and boarded the vessel that was in Port Fourchon in Southern Louisiana. And painted on the bow of the ship with oil from the BP spill “Arctic Next?” And it was at the same time that Ken Salazar was in Louisiana assessing the damage from the BP spill.

So we were, all seven of us were charged with two felonies with a maximum of 12 years. And the next day, Ken Salazar announced that he was putting a moratorium on Arctic drilling for a year, which was great.

[Applause]

There've been few moments in my direct action experience where there's been that immediate of a result. Those charges was about a year and a half long legal battle and we took a plea eventually.

Greg Dalton: Tim DeChristopher, you refused a plea, why?

Tim DeChristopher: Yeah. There were several reasons. You know, first off I feel like a trial is a great organizing opportunity that gives you a public platform to continue the same kind of public narrative that you were making in the action itself. There was, you know, in my mind, the plea-bargain does three things. It concentrates power in the hands of judges and prosecutors. It eliminates the role of the public in the justice system. And it resolves things quickly and quietly out of the public eye. And I think all three of those things are kind of antithetical to what we’re generally standing for as activists that are looking for more democratic participation more civic engagement, more distributed kinds of power. Then what I also understood after I was actually in prison and talked to a lot of other folks who had been pressured into plea bargains. Was also that plea bargains are the technical means for mass incarceration. It's the way in which we can funnel that many people through the justice system every year. So, you know, I think all of those are kind of cases against plea bargains, but I've also seen the tremendous organizing potential for trials as a new organizing platform.

You know, that was certainly the case in my own trial and all the organizing that went into that over the course of 2 1/2 years. .

Greg Dalton: Georgia Hirsty, you then after that incident in the Gulf you went to Portland, you arrive at the St. John's Bridge in the middle of the night. So tell us about that moment how you felt, you get there it's dark and you're going to jump off a bridge.

Georgia Hirsty: Well, the whole – people have been organizing against Shell for decades, and the summer just before Portland we were in Seattle and there was a really amazing coalition of groups and locals and folks in Seattle that were organizing against the Polar Pioneer the Shell’s drilling rig that was had already and at that moment that I was about to jump off the bridge was in the Arctic waiting to drill. So there was a lot of, you know, there was a lot of momentum already building around the campaign. And, you know, the chance that we had in Portland was really just being able to seize the moment because the Fennica had run aground. There were no, there hadn’t been plans to be in Portland and so we were really able to kind of capture that moment. So on the bridge before I stepped over, you know, thinking about the whole context of the campaign and the chance that we had knowing that we found a chokepoint, knowing that Shell couldn't drill as long as we could prevent the Fennica from leaving Portland was a pretty inspiring moment and fortunately it was dark and I couldn’t see how far away the water was.

Greg Dalton: So 13 people go over – you have a marine radio and then you see the Fennica and a drawbridge lifting it’s coming toward you. Take us to that moment.

Georgia Hirsty: Right. So we were 13 people across the span of the St. John's Bridge. And we were about 70 feet apart from each other because the Fennica at its widest point, is 85 feet so it was enough with 13 people to prevent it from going through at any point. When the Fennica came towards us, you know, I don't know exactly the distance between that drawbridge but it steamed right up to us and I hailed the Fennica on the radio and said in maritime protocol, that “This is the activists under the bridge and you are on a collision course and you’re putting people's lives at risk, please stop.” And they eventually radioed back and said “This is the Fennica we’re not going to stop so move” something like that and then I repeated my message we obviously weren’t in a position where we could move. And then they confirmed that they had stopped and you could see that the ship had stopped they no longer had a wake but there was this moment that seemed like kind of forever where everyone was waiting with bated breath. You know, the water was filled with kayakers there were, the activists on the bridge and no, we couldn't speak or talk to each other we were too far apart, you could feel the kind of the tension in that moment while everyone is waiting to see what the Fennica would do and whatever time in reality passed I don’t know. Eternity passed and then the Fennica slowly started to turn around and when it got about 90 degrees in the other direction you just heard before I even could react, you could hear the uproars of cheering from the quayside and from the water and then it turned all the way around and went back to its port.

Greg Dalton: And not long after that Shell announced that they were –

[Applause]

– for the foreseeable future suspending their operations in the Gulf. I contacted Shell for their comment on this whether this incident, what impact it had on their operations. And this is from a Shell spokeswoman: "Our decision to cease further exploration activity offshore Alaska for the foreseeable future was due to the drilling of a dry hole, high costs and an unpredictable regulatory environment. While we respect the views of these those who oppose Arctic exploration opposition to our projects in this Northwest US did not play a role in that decision.” That's Helen O'Connor from Shell Oil. Brendon Steele, what do you think about that direct action against Shell, was it the right approach to confront the company in that way or was there another way?

Brendon Steele: I think it depends on what your ultimate goals are. What your asks of the company are. We say at Future 500 that we can't do our work unless the advocacy community does its work. We work inside a number of companies, we work with a number of companies to help them engage stakeholders, it's a jargony term. And we always aim to find common ground in that process. We’re a 501(c)(3) nonprofit. And our concern at times, whether that's a certain campaign or overall strategic goal is what the main ask is. And in this case with the oil and gas industry we see that direct activism that civil disobedience has opened up the space for a price on carbon at the federal level. We feel that has been reopened in discussion with a number of companies, but that ask is not being made in a way that brings it out. And in fact, redoubling on parts of the oil and gas industry is actually closing them off to that possibility.

There’s a sense that the advocacy community is coming to them with an ask of to cease to exist anymore and that's not gonna open up the room for dialogue.

Greg Dalton: Tim DeChristopher, you want them to cease to exist. You don't think that they're part of a transition, that they have to die and something green has to grow somewhere else.

Tim DeChristopher: Yeah.

[Applause]

Yeah, I think that is the position of fossil fuel abolition; that we actually need to keep fossil fuels in the ground. We need to build an energy economy that actually works for people and for our communities and our society and for future generations. And the fossil fuel industry as it exists now doesn't have a role in that future. I think that regardless of how big a role they might've played in our past. I think their time is done.

Greg Dalton: That gets an applause and it sounds good but realistically, think about everyone in this room, everyone listening to this use fossil fuels today and will use fossil fuels tomorrow and it’s so deeply embedded. I mean, is that realistic that all of them can’t play any role and that suddenly we’re gonna drive solar powered cars. I haven’t seen a solar powered car yet, I mean how realistic is that Tim DeChristopher?

Tim DeChristopher: I mean I think 200 years ago, you could've said the exact same thing about slavery and the way that our entire economy was touched by slavery. And you couldn't interact with our economy without in some way benefiting from slave labor. And --

Greg Dalton: And the cost of getting off slavery was a lot less than people argued at the time. Robert Kennedy Jr. has written some articles about this, okay. The cost of getting off slavery was less than the slave owners argued at that time.

Tim DeChristopher: Yeah. And I think, you know, we have solutions that are actually being resisted by the fossil fuel industry. That we, it's been I think it's been clear that we cannot unleash the solutions that we have until the fossil fuel industry gets out of the way. That they’re standing in the way of our progress. And that doesn't mean it's an overnight transition, it doesn't mean that the fossil fuel industry is gonna cease to exist tomorrow, just like as a prison abolitionist, you know, I don't expect every prison to be bulldozed tomorrow and everybody released. But it means that that's the goal that we’re working towards and that's our – that's the vision of a truly healthy and clean energy economy that doesn't involve fossil fuels.

Greg Dalton: Brendon Steele, doing away totally with fossil fuel companies, no role in the future, what do you think?

Brendon Steele: I think during our lifetime it's likely not gonna happen. I think that there is the possibility to negotiate with fossil fuel industry to create a system in which economies around the world eventually decarbonize but I'm concerned that a pipeline by pipeline and, you know, train by train battle against the fossil fuel industries a losing battle. And you can knock out the Exxons or the BPs of the world but then you look at the state owned oil companies the Saudi Aramco, the Gazprom the Venezuelan state owned oil company. And compared to the Exxon Mobil those guys are they are the giants and they wield immensely more power and I don't see them going away anytime soon.

Greg Dalton: Georgia Hirsty, the Keystone XL pipeline was recently rejected by President Obama. The environmental movement hailed that as a victory. Other people would say that that didn't, might have, may feel good but it doesn't keep any oil in the ground because the oil that would've gone to pipeline is going on trains, is going on other pipelines. So what do you think, was that a feel-good victory or was that a real keep it in the ground victory?

Georgia Hirsty: I think that it was a victory. I think that it's difficult to quantify the full range of effectiveness of direct action and the work that people did fighting the Keystone XL pipeline. I think that direct action is often about empowering people and shifting the national and international narrative around these things and bringing things to the focal point of the national and international conversation and attention. And so you start to see these bigger shifts in the conversation in the way that people engage in people's general kind of paradigm about fossil fuels, about corporate power and influence. And so I think there were so many small and big actions in organizing around Keystone XL and I think that it is absolutely a victory in addition to empowering an entire generation of people that are going to continue to take action, continue to organize and continue to really stand toe to toe against the oil industries.

Greg Dalton: Tim DeChristopher, Sean Penn has been in the news a lot lately for going and meeting with El Chapo and he admitted to Charlie Rose that he had failed in his message and what he was trying to say is that there is a supply and a demand. That the supply is villainized and that there’s also a demand that Americans are culpable, have a role in the failed war on drugs, that Americans, as consumers are part of the problem, not just bad Mexican drug lords. Transition that to fossil fuels; attacking supply really works. It has to be on the demand side as long as there is demand the supply will be there to meet it and we are all part of the demand.

Tim DeChristopher: I think, particularly in fossil fuels, I mean I think this is true in most of our economy, but particularly in fossil fuels what we have is a manufactured demand. We have a company or an industry that exercises immense power over our government to make sure that there's demand and reaps massive subsidies to distort that market economy. So that, you know, even though we’re only paying a few dollars a gallon right now for gasoline, we’re paying $10 a gallon, at least in our tax bill through subsidies. So, you know, you can work on trying to convince people to change their consumer behavior, but structurally we’re still giving massive support to the fossil fuel industry through our government. And I think it has to be addressed at that level and –

Greg Dalton: We don’t have a lot of choices. The markets not giving us choices, Brendon Steele, right? It’s kind of, the market’s rigged in favor of fossil fuel companies.

Brendon Steele: I'm certainly not gonna argue against the power of the fossil fuel industry in the United States to influence subsidies and things of that nature. But I think it takes away some of the what I consider to be the facts that fossil fuels are desirable for certain reasons. They have a certain amount of energy density when you burn them they produce a lot of energy. Batteries can't mimic that sort of energy density. They’re easily transportable whereas alternative forms of energy are not. So my concern is that even without the subsidies those inherent qualities of fossil fuels make them a very attractive option. And even if you were to remove all the subsidies within Washington DC, remove the power of the oil industry, you still have a global cartel. If you're looking at oil for example, Saudi Arabia can adjust its output to the price it wants, drop the price of oil. And if we got rid of the American oil companies the fossil fuel subsidies in Washington that might be their dream because then they'd have control and the ability to drop the price, so that we couldn’t say no.

Greg Dalton: Brendon Steele is the Director of Stakeholder Engagement at Future 500. Our other guests today at Climate One are Georgia Hirsty from Greenpeace and Tim DeChristopher, founder of the Climate Disobedience Center. I'm Greg Dalton.

Tim DeChristopher, you said you've studied social movements. Recently we celebrated Martin Luther King Day. So how does the climate will be compared to civil rights, marriage equality, women's suffrage; what do you see there as a student of those movements.

Tim DeChristopher: You know, one of the movements that I look to as an example most is the women’s suffrage movement. In part because, you know, from the time of the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848 until around 1910, 1913, ‘14, there was a little bit of tangible progress that they had made, but in terms of major changes that they could hold up and say we've made this progress, there was actually very little. They had done I think a great deal of education over that time period, a great deal of subtle cultural shifts. But they had often approached their campaign, particularly in the time of like the 1890s to 1910 with the kind of appeasement strategy, kind of begging for their rights rather than demanding their rights. And so they had built up this mass of the middle ground that said, yeah, maybe women should have more rights one day but, you know, we don't wanna go too fast in that direction.

And then around 1914, a woman named Alice Paul came into leadership of the movement and she started saying we shouldn't be begging for our rights, we should be demanding our rights. And so she started leading the movement in much more confrontational strategies and doing things like sit ins and demonstrations and protests in front of the White House and in front of the Capitol building where women were getting beaten up by cops and dragged off to jail and doing hunger strikes in jail.

And presenting the nation with these really shocking images, especially for the time. And kind of forcing that comfortable middle ground into a choice where there was no longer this ground of oh yeah maybe one day women should have some more rights. And it was suddenly a choice between either immediate suffrage, immediate rights to vote for women, or the continued violence and oppression of women, which was now clear that that was the status quo, that that was occurring. That the sort of subtle violence of the denial of rights was now dramatized in the very clear violence against women in front of the capital.

And so they forced the nation into the choice and I think in part because of the decades of ground work and public education that they had done, the nation came down on the side of suffrage and they were able to get a constitutional resolution very quickly. And, you know, I look at the last 30, 40 years of the history of the environmental movement that I think has done a lot of that public education work and build up a lot of that comfortable middle ground that says yeah, clean water and clean air is important and we should do something about that fossil fuel problem one day. You know, I think we’re in a position where if we presented the nation with a enough of a shocking image that dramatized the reality of climate change, which is a form of violence and oppression against young people, and forced the nation into a choice between either an immediate transition away from fossil fuels or the continued violence and oppression against young people, which is clearly what climate change is, I do think that we’re in a position where we could come down on the side of choosing to stand against the fossil fuel industry.

Greg Dalton: Because one of the challenges for climate is that people – it's hard to see victims of climate. Polar bears, glaciers are remote and far away for most people; it’s not like your friend who’s gay, who’s in the closet or a woman who can’t vote or an African-American person you like, right it doesn't have the human face that is the victim of climate. But I guess you’re saying that that every person under a certain age is the victim.

Tim DeChristopher: Well, I mean I think, you know, all of – so it’s a form of generational oppression and so that's always relative. So everyone who's now living is facing some negative impacts because of those who have come before us. And all of us are reaping great privilege at the expense of those who will come after us. But part of the reason that there's not a better face on climate change is just the failure of our public leaders to do a better job of connecting the dots. You know, that one of the one of the greatest humanitarian crisis on the planet right now is happening from the refugees streaming out of Syria and the terrorist groups like ISIS that have formed out of that situation, which was a civil war that was largely triggered by a climate -induced drought, according to the CIA. They list that as the major factor that set off that situation. You know, so when we look at the movements that are really capturing a lot of public attention right now like Black Lives Matter – I think they've done a better job of connecting the dots so that when a young black kid gets shot by the cops, you know, it's the bullet that kills the kid and yet our public has been able to connect the dots enough to say that, oh that's not just the bullet that kills kids, it’s not just this isn’t just an issue about guns and this isn’t just an issue about crime because police are involved.

But this is a more structural systemic issue about white supremacy that pervades our whole society. That actually I think took a lot of work from a lot of activists trying to connect those dots over years and decades. You know, I don't think it's, I don't think it's implicitly any harder to connect the dots between the kid who dies from a bullet in a civil war in Syria to the climate change that triggered that situation. I just think it takes that much effort of public leaders that are willing to tell that story and connect those dots.

Greg Dalton: Tim DeChristopher is founder of the Climate Disobedience Center. I’d like to go to our lightning round with a quick yes or no, true, false question for each of our guests starting with Georgia Hirsty. Melting glaciers and struggling polar bears are not convincing images for most Americans who will never see a glacier or a polar bear in person. True or false?

Georgia Hirsty: True.

Greg Dalton: Tim DeChristopher, the Paris climate agreement is an important step toward stabilizing the planet and the economy?

Tim DeChristopher: False.

Greg Dalton: Tim DeChristopher, President Obama will have a legacy as a climate leader, yes or no?

Tim DeChristopher: False.

Greg Dalton: Georgia Hirsty?

Georgia Hirsty: False.

Greg Dalton: Brendon Steele, fossil fuels have brought humans out of the dark ages and lifted millions of people out of poverty. True or false?

Brendon Steele: That was two parts. And I’ll say no and yes.

Greg Dalton: So, no to the dark ages –

Brendon Steele: No to the dark ages –

Greg Dalton: – and yes to poverty.

Brendon Steele: Yeah.

Greg Dalton: Okay. Late last year, congress reached a Bipartisan Budget Deal that lifted a ban on petroleum exports and extended solar and wind power tax credits for five years. Georgia Hirsty, good deal or bad deal?

Georgia Hirsty: I don’t know enough about it.

Greg Dalton: Brendon Steele, exporting petroleum and extending renewable power tax credits?

Brendon Steele: Good deal.

Greg Dalton: Tim DeChristopher? Some brown, some green.

Tim DeChristopher: I’d come down slightly on the side of bad deal.

Greg Dalton: Tim DeChristopher, if you had to do it over again, would you bid on those natural gas leases in Utah knowing you would spend two years in prison?

Tim DeChristopher: Yes.

Greg Dalton: Georgia Hirsty, did you tell your parents you were going to hang off the bridge to stop an oil rig before you did it?

Georgia Hirsty: I told them, I told my father that I loved him.

[Laughter]

I can’t really tell all the details.

Greg Dalton: Okay. Brendon Steele, Future 500 sometimes apologizes for fossil fuel companies?

Brendon Steele: No, or false.

Greg Dalton: Georgia Hirsty, do you have friends who disagree with you on climate and fossil fuels?

Georgia Hirsty: Yes.

Greg Dalton: Tim DeChristopher, do you have friends who disagree with you on climate and fossil fuels?

Tim DeChristopher: Yes.

Greg Dalton: Brendon Steele?

Brendon Steele: Friends no, family, yes.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: Okay, how they do? I think that’s the end of our lighting round. I think they did pretty well. Let’s give them a round of --

[Applause]

[Climate One Minute]

Announcer: Maria Gunnoe is a coal miner’s granddaughter. She lives on a farm in West Virginia that’s been in her family for three generations. When runoff from mountaintop removal polluted her wells and streams, she fought back for cleaner, safer mining practices. Gunnoe hadn’t planned on taking on the coal industry. But as they found out, she was more than equal to the task.

Maria Gunnoe: I didn't really get into fighting the industry; the industry took me on. I tended to my family property. That's what I'd done. And in doing so, I realized in 2001 that I was going to have to fight mountaintop removal in order to protect this property and it just seemed like an astronomical task. And it has been. But yeah, they took me on. They challenged me and my love for my property is what pushes me forward.

Greg Dalton: And were you threatened?

Maria Gunnoe: I've been threatened many times, yes. And my children overheard these threats. And my son was only 16, 17 years old and he was in the last years of school when he looks at me and says, "Mom, I can't go to sleep. I heard what they said at the football game. They're going to burn us out tonight." Well, that's when we realized that we're going to have to have security in here.

Greg Dalton: Did you ever think of giving up?

Maria Gunnoe: No.

Greg Dalton: Moving?

Maria Gunnoe: No.

Greg Dalton: Do you think they knew who they were messing with?

Maria Gunnoe: No.

[Laughter]

Announcer: Maria Gunnoe was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize in 2009, and she told her story at Climate One last year. Now, back to our live program with Greg Dalton at The Commonwealth Club.

[End Climate One Minute]

Greg Dalton: Brendon Steele, Future 500 is working with some Republican donors who are coming out of the closet on climate. So tell us about Jay Faison and Trammell Crow and some of the other people you are working with.

Brendon Steele: They are, so Jay Faison, Trammell S. Crow and Andy Sabin are three billionaire donors to the Republican Party, major donors. And they are all as I would say rapidly pro-climate. They’ve not been aligned with the Republican Party on climate and environmental issues and for most of their lives they've been mostly lone wolves on the issue and in the party.

It's been fascinating to see how they perceive their limitations as donors; sort of being a non-billionaire, I perceive a billionaire donor sort of having limitless power, but it's been fascinating to see both in the oil industry and in the donor class the perceived and real limitations to power. It’s been over the last few years that these three donors have come to know each other and are beginning to strategize about how they can influence the party to change. You’ve seen on the news for example, Andy Sabin has been working behind the – well now flailing Jeb Bush campaign to make climate an issue, not a campaign issue, but one that if he were elected would be a priority for his administration. We’ve seen Trammell S. Crow reengage the party, reengage some of his donations but with the requirements of each of his donations that certain individuals within the GOP have meetings, interact with climate advocates of his choice. And so it's been fascinating to see this part of the donor class the party begin to mobilize in favor of climate.

Greg Dalton: Have they had any influence yet, I mean at the federal level that’s pretty tough. Where they had any influence?

Brendon Steele: You know I, I think time has been too short to see, especially in the climate issue. You know, Andy Sabin has worked mostly on water issues and conservation issues across the globe. And has had more success there but Jay Faison's operation is brand spanking new, it's a really short amount of time to judge results.

Greg Dalton: He's pledged, he’s a North Carolina entrepreneur who has pledged $175 million to work on climate, something like the Tom Steyer of the right. Tim DeChristopher, do you, what do you think of engagement with Republicans like that, or do you want to do away with the Republican Party like you want to do away with the oil companies?

Tim DeChristopher: I don’t necessarily want to do away with the Republican Party. You know, I think engagement with grassroots conservatives is very productive. You know, I spent most of my years as an activist in Utah, which is not quite as progressive as here in San Francisco. You know, and – and I actually had a great relationship with a lot of conservatives in Utah and found a lot of common ground. But I think that was more addressing the grassroots folks on the right. That I think there's much more of a potential there. I mean, I don't think that the left-right spectrum of our political system is really realistic; to me it's more like a steep pyramid where a lot of us at the bottom have more common ground on either the left and or the right than we do with the folks up at the top. And I think particularly at this point when it's abundantly clear that it's too late for any amount of emissions reductions to limit climate change to a point that is not extremely catastrophic. That has a serious level of hardships that are that are now inevitable. You know, I think organizing on climate change at this point has to take into account the fact that we are going down a rocky and chaotic road of extreme change. And so it becomes all the more important who is steering the ship as we go down that course. And what kind of power structures do we want to have in place when we go down that desperate path. Who do we want to be holding power and calling the shots?

Greg Dalton: Georgia Hirsty, Tim DeChristopher mentioned a rocky road. I had a conversation recently with a friend, small business owner in San Francisco who said “All my liberal friends in the Bay Area are hypocrites. They pretend to care about climate; they fly in airplanes, they ride in taxis.” Do you think that we can really address this climate issue and pretend that if we just put a little solar, buy electric car we can live our lives and still be go along our merry way or is it gonna require some lifestyle change?

Georgia Hirsty: I think that it will necessarily require lifestyle change as things become – as we go down that road. However, I don't think – this comes up a lot. And I think you mentioned earlier, when you talked about the lack of choices and so there's, well lifestyle activism and the choices that we make in our individual lives are important. There's also a system that's rigged against us and corporations and rich people who influence the political and cultural framework of our country so much that we’re left without options and so really being able to address that. So yes, maybe that we’re hypocrites in that way. But I think that the conversation should be about the bigger framework that we’re operating under and the confines that this kind of hyper capitalism that we live in now where the people who have the most power is what – where the power is concentrated is what dictates the rest life for the rest of us is really where the conversation needs to be.

Greg Dalton: Like that lifestyle activism. Tim DeChristopher, is the middle class in denial, the climate conscious people are they gonna have to make more sacrifices and changes than they like to believe?

Tim DeChristopher: I think it's more than the middle class that’s in denial. I think it's all of us in one way or another. You know, I mean even though I said earlier that I think we have a lot of renewable energy technologies that can meet our needs, I don't think there's any energy technology that can produce enough material goods to meet our human and emotional needs. And as long as that's the mission of our economy to fulfill our spiritual and emotional needs with consumer goods we’re never going to get there and we’re always gonna have an ecologically insane kind of economy. So, that's actually I think a fundamental shift towards a society that starts meeting its human and emotional needs with human relationships, rather than trying to identify ourselves only as consumers and find our self-worth in our material consumption and that sort of thing. That's gonna have to shift, you know, but I think the positive thing on that side is that we've never had an energy source that has been able to do that. That's always been a failed mission of our economy that doesn't actually make people happier anyway. You know, that's always led to dissatisfaction by trying to fulfill that spiritual part of ourselves with consumer goods. So I think that's kind of a positive shift.

Greg Dalton: Remember Bill McKibben writing that one of the major, I mean accomplishments of the last few decades is building bigger houses further apart and wealth has gone up and happiness has gone down.

Let’s go to our audience questions. Welcome to Climate One.

Greg Dalton: Let’s go to our next question.

Carter Brooks: Hi, my name is Carter Brooks. I’m an artist and philosopher of Climate Art. Tim, you mentioned your origin story I suppose with Terry Root being more honest with you in describing your own period of despair and coming out of that. So my question is about courage, honesty and despair. There’s a tendency for us particularly climate activists to avoid anything that might possibly lead anybody into despair. And so we’re, I think not quite honest with ourselves about the scale of our issue. And the trope is well, if anyone goes into despair they’ll just be inactive. You’ve proven that to be otherwise and I wonder whether you could comment about that a little bit.

Tim DeChristopher: Yeah, that's something that that I've spent a lot of time thinking and talking about. And these things that are called negative emotions in our society like sadness and despair and fear and anger. You know, I really think that they actually have a critical role to play and can help ground us in reality. And I think particularly with despair and I think it takes a lot of effort to deny despair. And I see a lot of folks in the climate movement that wastes so much of their efforts fighting off despair. And I think that when we stop wasting our efforts on fighting that off and acknowledge that as like an honest part of ourselves and an honest part of who we are at this point in time, we can move forward much more productively.

And when we’re honest with each other, we stop pretending and making each other feel crazy. Because the fact is that a lot of people are feeling those things and when we repress them because we’re told that we’re not supposed to have despair and we’re not supposed to have anger, when we repress them then other people think who are feeling that inside but not seeing it honored by anyone else, they think, oh something must be wrong with me. I must be a crazy person, you know, which is extremely demoralizing. But everybody's feeling like something must be wrong with them because they're feeling what nobody is willing to talk about. And I think our challenges are so great in this movement that we can't afford to just have like the convenient side of people in this movement and in this broader work. I think we need to be willing to be full people, to bring our full selves, including our anger and our sadness and our despair, and mobilize all of that strength that comes from it towards this challenge.

Wayne Roth: Hi, my name is Wayne Roth. I think of myself as a climate activist but in front of you I don’t think I’m doing as much as I can and would like to do more. That despair that you’ve gone through I think I’ve gone through that. I appreciated that honesty, but I don’t know how to get people to recognize just how bad we are disturbing the planet’s geological and climate systems.

And I’m frustrated with that. And perhaps you can help me if you will talk more about the Climate Disobedience Center because that maybe an organization that I would like to donate some of my time and energy towards.

Tim DeChristopher: Yeah, and I actually think those two issues are linked. You know, my answer to that first part of how to get people to realize how serious this is. Actually the best strategy that I know of is civil disobedience. I think it's a phenomenal tool for education because we can throw out lots of facts and figures about how serious the climate crisis is and generally those kind of bounce off people. All the folks who could be deeply motivated by facts and figures I think have been motivated for a long time and that turns out to be a small minority. I think most people are moved more by human stories and what they see other people doing. And civil disobedience is a way of saying that the climate crisis is so serious that I am going to put myself in a vulnerable position to do something about it. And I think our vulnerability has a tremendous power to open people up, to rattle them out of their everyday, lethargic apathy of their consumer lives. And create a strong desire for them to connect to that vulnerable person that they see in front of them. And that opens them up to really be awakened. That's what I saw with the jury last week in Seattle and in with a lot of people that were engaged with that trial. And so the Climate Disobedience Center is an organization that is trying to facilitate more of that, trying to harness a lot of the growing commitment in the climate movement to take bold actions. And use that to really tap that full potential of climate – of civil disobedience to arouse the conscience of a community.

And so we’re supporting activists in any way that they need to be supported. Whether that's training in action support or whether that's trial support, legal support, financial support, whatever it might be. We kind of go wherever we’re invited to help people realize that full potential of civil disobedience.

[Applause]

Greg Dalton: We’re talking about climate disobedience at Climate One. We have a few minutes left; let’s go to our next audience question.

Male Participant: Hi, I’m Paul Taziminio. I’m with Amazon Watch. I wanna applaud your activism both of you and remind people that in addition to these cases where people are putting themselves and their lives in the line, many of the communities that we partner with in the Amazon and elsewhere who are on the frontlines of climate change are basically facing this life or death struggles every day. These fossil fuel companies are at their doorsteps trying to destroy their existence. And so, you know, we are fortunate here but there are people who are fighting this fight for us. And it frustrates me because we accompany these indigenous leaders to road shows like the ones that you went to. To auctions to present their truth to the people who are buying and selling their land. And yet the climate movement says, don’t talk about protests. Don’t talk, don’t say climate change, don’t say this don’t say that. Just say pollution or health, et cetera and they want us to basically try to make the message so that it can be received as broadly as possible and we will grow the movement. And for me, that frustrates me from my experience and I assumed that it does you and I’d love to hear from both Tim and Georgia about what their reaction is too.

Georgia Hirsty: Yeah, I think that certainly like as I was talking about before like switching the lens to one of environmental justice rather than environmentalism and actually talking about the reality of what's going on, the suffering that's going on, the risk that people are taking and the privilege that we have to choose to get arrested, to choose to do actions when people are being, you know, murdered or fighting these fights every single day. And I think it's very important for the climate movement to come over to the side of the environmental justice lens where we’re willing to talk about the people of color, the communities around the world that are struggling and that are on the front lines and that it's much more about people in that way than necessarily about trees and water, I mean interconnected of course.

Greg Dalton: We’re gonna go to our next question. Welcome. We got a few minutes left, welcome.

Female Participant: Hi. I am on the divestment campaign at the University of San Francisco. And it’s a question for all of you. Just tips and what you honestly think about the divestment movement.

Greg Dalton: So Brendon Steele, divestment. You actually advocate for constructive engagement with companies. So tell us about, is divestment a good idea?

Brendon Steele: I think the divestment movement has changed the cultural narrative. It’s been extremely powerful symbolically and I think it's been important to bring companies to the table and open up the space for a price on carbon. One thing I will say is that we see an untapped coalition. Jay Faison, who you've mentioned earlier, Exxon Mobil, Citizens Climate Lobby and James Hansen all advocate the same climate policy if you look at it. There's room to advance that even through the divestment movement, but the actual process of divesting from companies, I’m concerned actually disempowers the climate movement because you're dropping the share price and having people care less then buy in.

Greg Dalton: So, selling fossil fuel stocks is a bad idea. Tim DeChristopher?

Tim DeChristopher: I think the divestment movement first off, has been incredibly for as an entry ramp for young people into the climate movement. Whereas previously I think the easy kind of entrance ramp was through changes in consumer behavior. And divestment movement has been encouraging young people to start thinking about the institutions that they are part of and thinking about things systemically and leveraging that institutional and system power. Which I think is going to yield great benefits with this whole generation of young activists who are thinking about things systemically from an early age. And I think they're going to be a really powerful generation of activists because of that. In terms of divestment itself I think it clearly already is having an impact with companies like NRG citing that, as a major pressure source for why they're shifting their model. And, you know, the company engagement model I think was used by really powerful institutions. You know, like the Rockefeller family; they tried to shift Exxon through shareholder engagement and failed, and never had any success. I think shareholder engagement can make a difference at the margins with like some worker policies and that sort of thing, but when it comes to the core business model of a company who owns trillions of dollars’ worth of assets that are still in the ground, there's not gonna be any level of shareholder engagement that is gonna convince them to abandon those assets and leave them in the ground.

Greg Dalton: Let’s go to our next question. Welcome to Climate One.

Male Participant: My question is for Georgia or Tim, is in my mind, climate organizers have this daunting task of undermining the fossil fuel industry as well as engaging a population of ordinary folks who don’t work for organizations like Greenpeace or other big organizations or in government or corporations who feel powerless and are disengaged.

And I’m wondering what you all think is the best, some of the best pathways to engage folks to just not just turn out in large numbers, like it’s great to have people turn out for a big protest over a day. But also engage people to take like higher risk activity like the two of you did.

Greg Dalton: Georgia?

Georgia Hirsty: Yeah, I think a lot of the grassroots movements, the grassroots organizing that’s happened, particularly in the Bay Area where people have shown up in all of the kind of solidarity of issues so they'll be people that come to the warehouse for example, that are working on race that are oriented toward the environment, that are oriented toward gender. And build this campaign and can show up for each other as allies, can show up as activists, can show up as legal support. And what has been amazing over the course of the last two years in that space is to watch how people get increasingly more empowered and that solidarity and then more empowered to take action. Both for the issue that the issue that they're particularly fighting on but then also taking action in the way that all the issues are connected to one another. So I think giving people like a longer-term whether like strategic framework and the interconnectedness of all those issues where they feel like they're part of the community and growing together with every action they take has what really makes people more not only willing to take those risks, but more empowered by it.

Greg Dalton: We have to end it there. We’ve been talking about climate disobedience and climate change at Climate One with Tim DeChristopher, founder of the Climate Disobedience Center, Georgia Hirsty, National Warehouse Program Manager with Greenpeace and Brendon Steele, Director of Stakeholder Engagement at Future 500. I’m Greg Dalton. You can listen to this and other Climate One podcast in iTunes at the Climate One site, climateone.org. I’d like to thank our audience in the room and listening online. Thanks for joining us. We’ll see you next time.

[Applause]