The Fight Over Pipelines

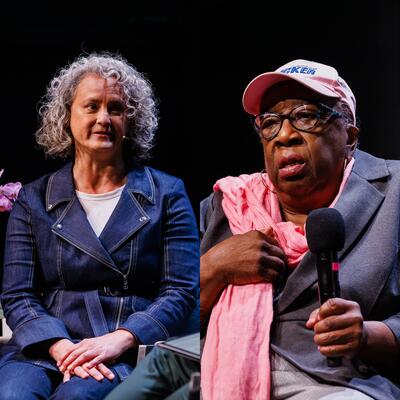

Guests

Mike Fernandez

Kelly Sheehan Martin

Daniel Raimi

Summary

Canadian company Enbridge is building an oil pipeline from the Alberta tar sands through Minnesota to the Wisconsin border. The new pipeline, which is nearly complete, is a replacement for the existing Line 3, built in the 1960s. That pipeline has a history of leaks, and Enbridge says the new pipeline will be safer and allow them to transport more oil. The company plans to start moving oil through the new pipeline in October.

Indigenous and environmental activists say the new route for Line 3 opens up more of Minnesota to risk of water contamination and locks in burning more fossil fuels for years to come. They’ve been protesting the construction with civil disobedience, leading to hundreds of arrests and serious clashes with police along the pipeline route.

We’re not going to get off fossil fuels overnight. But Kelly Sheehan Martin with the Sierra Club says we shouldn’t be building more pipelines.

“The science is telling us that we have to stop building fossil fuel infrastructure, new fossil fuel infrastructure today, if we want to avert the worst impacts of the climate crisis. Our window to act on climate is closing and Line 3 poses an unacceptable threat, not only to our climate but to land and clean water and tribal sovereignty,” she says.

Sheehan Martin says we need to listen to the voices of those most impacted by the climate crisis, and who object to a pipeline crossing their land and water. “Pipelines are one of the things that mobilize folks as a line in the sand, in part because they can traverse thousands of miles of land and so they impact people all along that way all along the proposed routes. They give people a voice in a place where they don't have a voice to speak up.”

Mike Fernandez with Enbridge says we still need to transport oil, and pipelines are the least carbon-intensive means of doing so.

“What we’re doing is what the Biden administration laid out all the way back in their campaign. We’re building back better. This is safer. This is cleaner. This is better,” he says.

As we move toward a less-carbon-intensive future, Fernandez says it comes down to what degree of dislocation we’re willing to tolerate. “This isn't an easy jump cut, you know, to move from fossil fuels over to wind, solar and other renewables. It really does require some level of transition and to be smart about it. And that's what we want to do,” he says. “We want to have those conversations around ‘how do we best get there.’ But you don't get there by certainly by just shutting things off.”

It’s no surprise that pipelines have become flashpoints in the debate over America’s energy transition. But Daniel Raimi, a fellow at D.C.-based Resources for the Future, says it’s difficult to quantify the impact of one pipeline on overall fossil fuel use and climate disruption.

“And any individual pipeline will have fairly modest effects on global and national gasoline prices in the United States. However, the local effects both environmentally and economically of pipelines can be really significant,” Raimi says.

“Burning fossil fuels in the United States was recently estimated to cost 300,000 excess deaths,” Raimi says. “And so, we know that there are challenges of the transition, but we are almost certain across the economics and policy community that the damages from letting climate change continue at the pace that we are currently at is unacceptable.”

Related Links:

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. Indigenous and environmental activists have opposed the Line 3 oil pipeline in Minnesota for years. As it nears completion, protests along the route have grown more intense.

Kelly Sheehan Martin: Why are we continuing to attack water protectors with violence and brutality? Why are we continuing to build new projects that we know are creating an unstable climate for our future?

Greg Dalton: The company building the pipeline says it’s not a new project but a replacement and necessary for oil transport.

Mike Fernandez: We’re building back better. This is safer. This is cleaner. This is better.

Greg Dalton: But how much does one pipeline affect fossil fuel use and climate disruption?

Daniel Raimi: Pipelines are relatively easy to focus on, but it certainly is not an efficient or cost-effective way to reduce emissions.

Greg Dalton: The Fight over Pipelines. Up next on Climate One.

Greg Dalton: Climate One’s empowering conversations connect all aspects of the climate emergency. I’m Greg Dalton. It’s no surprise that pipelines have become flashpoints in the debate over America’s energy transition. The world’s energy transition is the focus of the UN climate summit, known as COP26, set for early November. Between now and then, we’ll bring you regular reports on the run-up to the conference in Glasgow. Hurricane Ida and other extreme weather events underscore what’s at stake. Climate One correspondent Aman Azhar [AAAAH-zar] explains:

Aman Azhar: The Conference of the Parties, or COP, is a yearly event attended by the countries that have signed the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change—a treaty agreed to in 1994. Last year’s meeting was canceled because of the pandemic. This year will be the 26th COP summit—hence COP26, hosted by the United Kingdom. The conference is taking place at a time when countries across the world are experiencing raging wildfires, unprecedented heatwaves and catastrophic floods. So, how can COP26 demonstrate the urgency of climate action more than it has in the past?

Kaveh Guilanpour:

Firstly, it needs to demonstrate that the gap between the emissions reductions is closing rapidly. And the action is accelerating so that we are moving in the right direction to stay within the 1.5-degree Celsius limit of the Paris Agreement.

Aman Azhar: That’s Kaveh Guilanpour—Vice President of the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions—a climate policy think tank. He says secondly, COP26 needs to deliver on the promise of $100 billion in climate finance by 2020. Thirdly, COP26 needs to deliver on how the world is going to adapt to the inevitable impacts of climate change. But how will the summit deliver on those promises?

Kaveh Guilanpour:

Countries are expected to come up with enhanced ambition towards dealing with the climate crisis in terms of reducing their emissions and also to come forward with more climate finance.

Aman Azhar: In addition to committing serious money to the climate crisis, each country’s “nationally determined contributions” - or emissions targets- are critical. But as Guilanpour says, they are only targets. What will really matter is whether the major players will follow through on their promises.

Kaveh Guilanpour:

The major economies have significant influence, so, the G-20 countries will be very important. The fact that US is back on the climate agenda and engaging under the new administration of President Biden. China will be very critical because of its emissions and its economic strength and importance around the world. And of course, the European Union. I think India will be a crucial player, Brazil is traditionally very active. The least developed countries and the alliance of Island states, and they are the most impacted by the climate change and they are very vocal and have a lot of influence.

Aman Azhar: Adrian Salazar, Policy Director of the Grassroots Global Justice Alliance, argues that the business-as-usual approach to the fast unfolding climate crisis will not work anymore.

Adrian Salazar:

There historically has been troubling intermingling of the fossil fuel industry at the UN climate summit. There is a lot of concern that fossil fuel companies lobby and influence the international agreements coming out of the climate negotiations. And we cannot allow continuing pollution through some of these false solutions that some of these fossil fuel companies advance such as market mechanism loopholes and carbon offsets. It is time to get emissions down to zero. Period.

Aman Azhar: That means the COP26 is not just expected to demonstrate real climate actions but also bridge the public mistrust about market forces such as oil and gas companies and their outsized influences on political systems. So, there’s a big laundry list for the world leaders to sift through when they meet in Glasgow in November. And the world will be watching! For Climate One in Washington DC. This is Aman Azhar.

Greg Dalton: Canadian company Enbridge is building an oil pipeline from the Alberta tar sands through Minnesota to the Wisconsin border. The new pipeline, which is nearly complete, is a replacement for the existing Line 3, built in the 1960s. That pipeline has a history of leaks, and Enbridge says the new pipeline will be safer and allow them to transport more oil, including heavier crude. The company plans to start moving oil through the new pipeline in October. Indigenous and environmental activists say the new route for Line 3 opens up more of Minnesota to risk of water contamination, and locks in burning more fossil fuels. They’ve been protesting the construction with civil disobedience, leading to hundreds of arrests and serious clashes with police along the pipeline route. My guests today represent different sides of this debate. Mike Fernandez is Senior Vice President of Public Affairs, Communications & Sustainability at Enbridge. Kelly Sheehan Martin is Senior Director of Energy Campaigns for the Sierra Club. And Daniel Raimi is a Fellow at Resources for the Future, a think tank in Washington, DC. We’re not going to get off fossil fuels overnight. But Kelly Sheehan Martin says we shouldn’t be building more pipelines.

Kelly Sheehan Martin: The science is telling us that we have to stop building fossil fuel infrastructure, new fossil fuel infrastructure today if we want to avert the worst impacts of the climate crisis. Our window to act on climate is closing and Line 3 poses an unacceptable threat not only to our climate but to land and clean water and tribal sovereignty.

Greg Dalton: Mike Fernandez, oil pipelines were built across the US and Canada with little national attention and opposition. Why do you think oil pipelines have become such a point of contention in the past decade or so since Keystone XL became a national symbol?

Mike Fernandez: Well, one, I think climate change is real and as a consequence, people are focusing on anything and everything. The mis-engagement around Line 3, is that Line 3 is a replacement pipeline. If you don't approve of the replacement. There are the permits in place to continue with the old pipeline. The old pipeline has flaws and challenges which is why in conversations with the Obama administration, we decided that what we needed to do is replace that pipeline throughout much of North America rather than endure the cost as well as the risks. And the other thing to keep in mind here is that pipelines are but one way that we transport fuel, and the other options burn fuel in order to move it. So, if you’re doing it by train, you’re doing it by truck, you're doing it by ship, the reality is right now there is the demand for what already flows through the current line 3. The Line 3 replacement project will do this now more safely and with more concern for the environment as well as tribal cultural resources.

Greg Dalton: But why not do the replacement in the existing place of the existing pipeline rather than a new place, which is you know the indigenous people are being really impacted by this?

Mike Fernandez: Well, so, the first part of your question is right, the second part of the question is inaccurate. The reality is what took place is we did what you'd expect us to do is as we went through the replacement project one, lots of environmental impact assessments in fact, over 13,000 pages of assessment, more than 70 different public hearings which Sierra Club and others participated in including those parties that have sought to get this tied up in court. And the reality is all those groups have been heard all along the way. In hearing from those groups, the bulk of the modifications nearly all of the modifications were made in order to make sure that everything was more conducive to safety and to environmental protection. And in fact, I can point to very specific ones where we made changes because of requests coming from tribal communities.

Greg Dalton: Kelly Sheehan Martin, don't you think that a new pipeline is better than an old leaky one?

Kelly Sheehan Martin: I think that if the old Line 3 can't be operated safely then Enbridge should hire Minnesota workers to decommission it. It’s not an excuse for there to be a huge new pipeline that would carry climate-polluting tar sands for decades to come at a time when we can least afford it. And look, Line 3 has been the subject of so much controversy and so many years of review and legal challenge because people are rightfully concerned about the threat about the major threat of this pipeline of a new pipeline carrying hundred thousands of barrels per day of some of the dirtiest oil on the planet through their waterways and through their homelands.

Greg Dalton: Daniel Raimi, the tar sands oil is dirty, but it looks like this line is going to go into commission soon. It's going to operation soon. Do these battles affect gas prices? How does the market look at something? We’re talking about one piece of metal here in a big system.

Daniel Raimi: It’s a great question. And any individual pipeline will have fairly modest effects on global and national gasoline prices in the United States. However, the local effects both environmentally and economically of pipelines can be really significant. So, for example, if there is a spill from any given pipeline that’s gonna have a major consequence at a location. Suppose they’re uncommon, they're unlikely, but when they do happen, they could be devastating. Similarly, a unplanned shutdown of a pipeline can have major economic effects at either end of that pipeline, particularly on the receiving end where refining typically takes place. And so, moving away from fossil fuels absolutely is an imperative to avoid the worst impacts of climate change, but doing so in a way that is planned and in a way that allows the workers and communities to make new plans for their livelihoods would be a less disruptive way to move towards a low emissions future.

Greg Dalton: Well, Daniel let’s stay with you. What is achieved if a pipeline project is stopped, does it keep the oil in the ground or does it just is it like a balloon you squeeze it and it squirts out somewhere else?

Daniel Raimi: It’s somewhere in the middle of those two things. So, the effect of shutting down any one supply route from an oil field, let's say, is to raise the price of exporting that oil in some other way. So, if the pipeline were to shut down, the oil could be moved via rail, it could be moved via truck. It could be moved via barge. But those are more expensive ways to transport the oil. As a result, prices would go up a little bit and production would go down a little bit. It wouldn’t prevent all of that air from leaking out of the balloon, let's say, but a small percentage of it would be affected. So, let's say you reduce oil flowing through a pipeline by 100 units. That won’t reduce consumption of oil around the world by 100 units. It might reduce it by five units or 10 units or something like that. And so, calculating the exact effect of shutting down any single piece of infrastructure is actually really hard because it's hard to know how much of that air is gonna stay in the balloon.

Greg Dalton: Kelly Sheehan Martin, one activist said to me the basic strategy here for environmentalists is to raise the cost of business to incur pain upon the supply companies. We saw that may have some effect with Shell drilling in the Arctic. They sunk $7 billion in the Arctic and there were protests and Shell walked away from the Arctic, at least for the time being. Is that the strategy here is to kind of drive up the cost of these projects?

Kelly Sheehan Martin: I think that if clean energy was operating on a level playing field away with the oil companies and the fossil fuel companies then we would see a lot different outcome and a swifter transition happening toward clean energy. The industry enjoys billions of dollars worth of subsidies from the US government every year. And that means that we are promoting too frequently a business as usual approach. And I think,I would say that the people that are on the frontlines right now that are most impacted by this pipeline and similarly that are most impacted by climate change are out there because they are fighting for their livelihoods and they’re fighting for their survival. And I think that to say that the whole point is just to drive up the cost of business is really disingenuous.

Greg Dalton: Well, let's hear from -- we wanted to say that we invited both Winona LaDuke and Tara Houska to join this conversation and they were unable to. So, they would say, well, let's hear a clip from activist and indigenous Attorney Tara Houska.

[Start Playback]

Tara Houska: We have treaty rights that were guaranteed for this place. They’re in violation of that. They’re in direct violation of their own laws and we are not trespassing we are, this is our land this is our territory Enbridge is trespassing just like all the other companies in so many other places where sovereign nations have said no.

[End Playback]

Greg Dalton: Mike Fernandez, let’s get your response to that about the treaty rights and the sovereignty of land where this pipeline Line 3 is going through.

Mike Fernandez: So, actually what Tara just said is inaccurate in the sense that every time we build or rebuild a pipeline we are required when native lands are involved to go through a process that includes the Bureau of Indian Affairs. We did that with Line 3 and we did more. We did a complete cultural assets audit that was conducted by natives throughout every mile of the track throughout Minnesota. And none of this is impacting even historical lands that are in dispute between Native American communities and the federal government.

Greg Dalton: It does though, Mike, there are seems to be this history with Dakota Access Pipeline which maybe wasn’t your company. It’s true certainly in British Columbia and there's a well-documented history in the United States of industrial sources being placed in communities of color. There is systemic environmental racism at play where some of these dirty sources of pollution are placed in communities that don't have a lot of power.

Mike Fernandez: Well, I think operators need to act responsibly and that's what we've done. I mean, even in the context of Minnesota, which was kind of the lead into this conversation is that we’ve coexisted in Minnesota with the most sacred and productive lands and wild rice waters for over seven decades and we have thoughtful partnerships. The stretch of land that is actually used for the pipeline only intersects or abuts two native lands. Those tribes that are on those native lands approve of the pipeline replacement. We have over 700 workers that are working on the pipeline that are from the indigenous community. So, there's no thought here to try and to look past what are either the rights or what are the interests of any minority group nor any tribal community.

Greg Dalton: Let’s go to Daniel Raimi.

Daniel Raimi: I think there are two things that we need to try to hold in our heads at the same time. And these two things are hard to hold in our heads at the same time. The first is that there is a reality of environmental racism and discrimination in the United States. Our current infrastructure contributes to that. That includes pipelines; it particularly includes oil refineries which disproportionately impact black and brown people around the United States. And at the same time there are some tribes in the United States certainly not all but some who are supportive of increased oil and gas development and would be supportive of the economic benefits that come with it. And so, we need to try to understand that there's complexity here and that some tribes are going to be very opposed to this pipeline for a variety of legitimate reasons and others might be very supportive of it for reasons that from their perspective are legitimate as well.

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation about the fight over pipelines. Our podcasts often include extra content beyond what’s heard on the radio. If you missed a previous episode, or want to hear more of Climate One’s empowering conversations, subscribe to our podcast wherever you get your pods. Coming up, we discuss the environmental justice and tribal sovereignty perspectives on pipelines:

Kelly Sheehan Martin: Indigenous people people of color, black people in this country have been met with centuries, centuries of genocide and violence. That’s in fact what our country is in part built on. And I think that this is no exception.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. We’re talking about why pipelines are such a flash point with Mike Fernandez of Enbridge, Kelly Sheehan Martin of the Sierra Club, and Daniel Raimi with Resources for the Future.

Greg Dalton: As part of the Line 3 permitting process Enbridge set up a fund called the Public Safety Escrow Trust in May of 2020. These funds have been used to reimburse costs associated with maintaining the peace around the pipeline. What this means in effect is Enbridge is paying the cops who are tear gassing and shooting protesters with rubber bullets --

Mike Fernandez: Wait, wait, wait, wait, wait. I mean the reality is not that we set up a fund. We were required to provide dollars to a fund that is managed by a state regulatory body. We do not control the inflow or outflow of money other than to meet the request that's put forward.

Greg Dalton: Let’s listen to another clip of indigenous Attorney Tara Houska this time, speaking on Democracy Now!

[Start Playback]

Tara Houska: The level of brutality that was unleashed on us was very extreme. People were shot in their faces and their bodies and their upper torsos. I saw a young woman’s head get split open right in front of me. It was a really, really brutal scene and the arrest in person were also quite brutal, turning people face-down in the dirt and being extremely violent in a situation in which we were outnumbered by police at least 2 to 1. And many, many, many counties presently protecting this one place in which also happens to be a county where an actual murderer is still on the loose has not been caught. But there were somehow over 50 police officers in that one place watching water protectors.

[End Playback]

Greg Dalton: Kelly Sheehan Martin.

Kelly Sheehan Martin: Indigenous people, people of color, black people in this country have been met with centuries, centuries of genocide and violence. That’s in fact what our country is in part built on. And I think that this is no exception. Why are we continuing to attack water protectors with violence and brutality? Why are we continuing to build these projects, new projects that we know are damaging our water and our air and we know they are creating an unstable climate for our future. And I just can’t see why this is what we need to be doing or want to be doing when we have ways to meet our energy needs without it. And I will offer that in preparing for this I saw the essay that you wrote, Mike, and that talked about “Poetry and Fiction Don’t Tell the Whole Story” was the title of it. And it undermined the writing of Louise Erdrich who talked about the breathtaking betrayal of indigenous communities in Minnesota with the construction of this. I think the time for this kind of undermining of indigenous voices and especially of indigenous women is over. The time for that is far past. And it’s time where businesses and forward-thinking companies are investing in clean energy. They’re investing in the transition to clean energy; they're not locking us in to decades more of fossil fuel infrastructure that is going to really end life as we know it. And instead they’re investing in clean energy solutions and the transition that puts people to work building the kind of world that gives us clean water and clean air and a stable climate and that protects our integrity and protects our diversity of people in life on this planet.

Greg Dalton: Mike Fernandez, let’s get your response to that,

Mike Fernandez: Yeah, so, Enbridge has invested billions of dollars in terms of the energy transition with offshore wind, with solar. We’re greening our own operations in terms of how we actually operate these pipelines such that we’re again using solar and wind. And in addition, through our utility, we have the largest facility in North America using renewable natural gas. We are blending hydrogen in with our natural gas. We have carbon capture projects that we’re building in various locations. So, we get it we understand, we’re intent about building a bridge to the energy future. The challenge is how do we get beyond the political hyperbole that gets placed and misplaced in stories like Line 3, where, when we've dealt with law enforcement it’s been about, you know, we don't endorse violence we want to de-escalate. We want to honor peoples and respect people with their right to protest, but peaceful protest is one thing; when people bring ladders and billy clubs and tear up equipment and destroy property and trespass literally climbing fences and spitting at workers who were also indigenous people, that goes beyond the ken.

Greg Dalton: Mike Fernandez, around the United States 36 laws have been enacted that address protests aimed at fossil fuel projects according to the US protest law tracker. Critics say these laws impinge on the right of assembly and disobedience, Arkansas, for example perhaps the law that would punish an individual blocking a sidewalk with up to one year in jail. Does Enbridge support these laws?

Mike Fernandez: No, those things are ridiculous.

Greg Dalton: Does seem odd, you know, that we in our society as people can physically attack US Capitol police and maybe get a month in jail but you get a year for blocking a sidewalk. Mike, I also wanna come back to you. You say that we need this infrastructure. The Energy Information Agency, the world's authority on energy recently said we don't need any new investment in fossil fuel infrastructure if we’re gonna meet the Paris climate goals. The Minnesota Department of Commerce opposes Line 3 on the grounds of a questionable future demand for oil - that’s the business and energy establishment talking. What does that mean for Enbridge? What's the transition path if they’re saying we don't need more energy and fossil fuel energy infrastructure?

Mike Fernandez: So again, Line 3 is a replacement, it's not new. So that's a little bit different, and so if you are looking at where the demand for energy already exists, and there's no easy replacement. What you don't want to do is say okay we’re gonna shut down this line. Why? Because now we’re going to go ahead and we’re gonna move it by truck, by train or by ship and literally burn fuel to move fuel. And we've looked at this pipeline, we've made it better and the idea, what we’re doing is what the Biden administration laid out all the way back in their campaign we’re building back better. This is safer. This is cleaner. This is better.

Greg Dalton: Daniel Raimi, let’s get you on this.

Daniel Raimi: So, the recent report that you referenced from the International Energy Agency is focused on achieving net zero emissions by about 2050. And what the report says is that there is no need for new investment in new oil and gas producing fields. There is however some room for additional investment in some fossil fuel infrastructure. That said, it's a very low level of investment that would be needed and we are clearly not on track to get where we need to be to limit global temperature rise from 1.5°C or even 2°C by the end of the century. And I think what we’re seeing here is that there is a deep frustration among many, particularly those in the environmental advocacy community that we are not on track to hit these targets and that the federal government in the United States as well as most governments around the world are far off track from doing what we need to do to have a healthy environment in the decades and centuries to come. And so, when you have that frustration, I think there is an understandable desire to focus on pulling any lever that is available. And in many cases pipelines are relatively easy to focus on they’re relatively easy to tell very compelling and important and real stories about the people who are affected by those pipelines, but it certainly is not an efficient or cost-effective way to reduce emissions.

Greg Dalton: Right. I've talked to environmentalists who say this pipeline by pipeline is a game of whack-a-mole. You stop this one but another one comes up over here. But they are good organizing or mobilizing political tools. Kelly Sheehan Martin, your response to that, you know, a lot of the environmentalist attack supply. It's easy organize and villainize companies, but it's much harder to tackle demand which involves donors and members of environmental groups. So, what’s happening on the demand side? Isn’t that a more effective place of focus?

Kelly Sheehan Martin: Well, they’re both effective places to focus because the climate crisis is here on our doorstep and we need all hands-on deck. And so, absolutely on the demand side we are retiring nearly half of the more than half of the coal fleet in this country has been retired in the recent decade. We have clean energy coming online to meet our electric needs at a rapid pace and in a way that leapfrogs the need for fracked gas plants. We have investments happening in clean transportation that reduces the demand for oil absolutely. And I think we’re seeing major progress on all of those fronts. And on the supply side, part of that comes from what we know from the UN Production Gap Report is telling us that we have no room in the carbon budget if you will. We have no room to expand oil and gas infrastructure if we wanna meet our international climate targets. And often the fossil fuel companies are the ones that are blocking that kind of policy level progress at an international and national scale. And pipelines are one of the things that mobilized folks as a line in the sand, in part because they can traverse thousands of miles of land and so they impact people all along that way, all along the proposed routes. They give people voice in an otherwise place where they don't have a voice to speak up. And I’ll just, you know, I’ll just say that this idea that demand is out there I think is very suspect at best. We, as you mentioned, we have not seen an adequate demand that we need tar sands oil from the Line 3 project. And I think that often we see the oil companies fabricating demand or even bolstering new markets for oil and gas as a way to justify continued profits from building pipelines and from extracting the oil.

Greg Dalton: Daniel Raimi, one thing that seems to be a real game changer here is the move of the auto industry which is, basically the global auto industry said we’re not gonna make any gasoline cars in 10 or 15 years. That's gotta have, you know, you did a report a couple years ago looking at rising global energy demand over the next few decades. Most of the lines went up. Does the shift of the US auto industry bend these curves and significantly affect the demand for oil that’s going through these pipelines we’re talking about?

Daniel Raimi: The short answer is yes; it makes a substantial difference. The electrification of the passenger vehicle fleet is going to dramatically reduce demand for petroleum products, gasoline and diesel here in the United States. But it's also important to remember that as we electrify the passenger vehicle fleet there’s a whole lot of other vehicles that run on gasoline and diesel that are much harder to electrify. If we’re thinking about long-haul trucking. If we think about aviation, if we think about long-haul shipping, many of these things can be electrified to some degree, but some of the other ones we really don't have economic solutions for right now. And so, as we seek to electrify the low hanging fruit if you will we also need to be investing in new technologies that can help us to decarbonize these harder to abate sectors whether it's long-distance transportation or manufacturing steel and cement or other technologies where we know we need to get the emissions out of the system but we don't quite know how we’re gonna do it yet.

Greg Dalton: Right. And that's where perhaps hydrogen can come in and help with long-haul trucks. Mike Fernandez.

Mike Fernandez: Yeah, and I think we have to continue to remember too what's the source of electricity. If we look today at where the largest number of electric cars exist, they exist in China, and China’s primary source for electricity is coal. That's not exactly where we want to end up. Similarly, what you also need to keep in mind is that fossil fuels are used for many day-to-day goods, including the headphones we’re using for this interview, the computers that we’re using in order to conduct this discussion as well as well as our own handsets that sort of guide our everyday life. And even those automobiles the bodies of those automobiles are significantly made from products that originate from fossil fuels.

Greg Dalton: Right. So, there might be a future of oil companies as being plastics companies, which as far as the climate is concerned, if we don't burn it that's good. Mike Fernandez, a small hedge fund gathered support from BlackRock and other huge investors to elect three insurgent members of the board of Exxon. That was a rare and stinging defeat for Exxon's leadership. What do you make of that moment and could something like that happen at Enbridge or other energy companies where investors are saying, protecting their financial investment and they don't see that they see a faster transition?

Mike Fernandez: No, I think that's right. I think what you're going to continue to see is more activism on the part of investors. I’ve worked for many different industries and I’ve actually overseen the investor relations function for a lot of different companies. And what has been interesting is over the last decade the increasing number of questions coming from analysts first in Europe but increasingly Europe, United States, Canada and a few other places around how companies are responding to ESG and in particular the biggie in terms of the environment.

Greg Dalton: Right. So, we’re gonna see more pressure. Enbridge has some wind, some solar. What's the exit path when Enbridge says, look, we’re not gonna do anymore pipelines we’re gonna only do wind. When are you gonna walk away from the dirty stuff?

Mike Fernandez: So, part of what you have to do and demand isn't created I mean demand is something that is out there despite what Kelly suggested earlier. We wouldn't want infrastructure if there was no customer for it. It doesn't make sense. It doesn't make sense to our investors. It doesn't make sense to our businesspeople. But at the same time there is an opportunity to rethink how these rights-of-way already exist. If you think about whole other industries in terms of like the laying of fiber for telecommunications of the United States. Most of that got laid alongside railway tracks. So, where rights-of-way already exist for infrastructure the same rights-of-way can be used to help the infrastructure associated with renewable energy.

Greg Dalton: You're listening to a conversation about building new pipelines as the US transitions away from oil and gas. Coming up:

Daniel Raimi: Burning fossil fuels in the United States was recently estimated to cost 300,000 excess deaths here in the US. And so, we know that there are challenges of the transition, but we are almost certain across the economics and policy community that the damages from letting climate change continue at the pace that we are currently at is unacceptable.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. My guests are Kelly Sheehan Martin of the Sierra Club, Daniel Raimi with Resources for the Future and Mike Fernandez of Enbridge. We are talking about oil pipelines--why they are so contentious and how they fit into a less-carbon-intensive future. The Atlantic Coast gas pipeline was canceled. The Keystone XL oil pipeline is dead after a decade-long battle. Penn East is another pipeline that seems to be on the ropes. I asked Daniel Raimi if the tide is turning against big new pipelines.

Daniel Raimi: I think they are facing increasing costs for many of the reasons that we’ve already talked about today. Part of that is the additional environmental reviews that are required when folks from the environmental community are active against these projects. And so, I think you can sort of chalk that up as a win for the environmental community in being successful in slowing down some of these projects. At the same time one of the concerns that comes to my mind when we fail to build new infrastructure projects in the United States is that transitioning to a clean energy future is going to need lots and lots and lots of infrastructure. Building transmission lines across the United States is not an easy thing to do, but it is absolutely an essential part of transitioning to a zero emissions future. The same thing is true for citing new wind and solar facilities we’re gonna need to build these things at enormous scales and we’re gonna need to do that despite the fact that there are tools in the regulatory toolkit that those who are opposed to that infrastructure can use whether it's to oppose on oil and gas pipeline or oppose a windfarm or an electricity transmission line.

Greg Dalton: Kelly Sheehan Martin, there’s a big infrastructure package trillion dollars coming through. It's not quite clear to me if it's actually been finalized yet. Some environmentalists are disappointed with the climate components of that. How do you see the Biden infrastructure package with respect to climate?

Kelly Sheehan Martin: I am hopeful. I think there are much needed investments in clean energy infrastructure and infrastructure that will make us more resilient to climate change that we will absolutely see in this package. And I think we’ll also continue to see improvements through the reconciliation process. And I’d like to see us remove fossil fuel subsidies as part of that as well so that clean energy can compete on a level playing field. I just want to go back to something we are talking about a minute ago. I think this argument that we hear all the time that is about well we use oil we each use plastics, etc. it’s such an unimaginative and old and outdated argument. Sure, yes, we are all part of the transition. And let's talk about what's next, let's talk about how quickly we can transition off of fossil fuels instead of doubling down on this necessary evil argument that gets us nowhere.

Greg Dalton: Mike Fernandez.

Mike Fernandez: Yeah, we’re all keen for that transition at Enbridge we committed to net zero by 2050 one of the first in the industry.

Kelly Sheehan Martin: You know, we’re not all keen to it if we’re also investing in new fossil fuel pipelines. We’re not. And so, this notion that --

Mike Fernandez: And we are on track in terms of reducing carbon intensity by 30% by 2030. It’s nice to be talked over, nice to be engaged with political hyperbole but the facts are the facts.

Greg Dalton: Well, that net zero and that’s kind of the coin of the realm these days are companies to pledge net zero but a lot is in the details there, Mike Fernandez, whether that includes offsets or there can be some sleight-of-hand there. So, and how is Enbridge gonna be net zero and are you gonna rely on offsets that have a very questionable history?

Mike Fernandez: No and part of it for us as I said earlier, is how we are going about managing our own operations. You know, so that much like we saw what happened when the Colonial pipeline got hacked back in May of this year and it had catastrophic circumstances. We know that electricity and digital plays a big role in managing these pipelines. And so, the electrical elements that we are using to manage that increasingly are being managed by renewables.

Greg Dalton: Right. Most of the impact is from consumer end-users - people, I don't drive a gasoline car, but people who do, right. So, it’s not, you know, Enbridge's own corporate operations are a small piece of it. It's really the consumer burning that fuel. Mike Fernandez, oftentimes there’s an argument that, you know, changing will have a cost. We got to do this but what’s less often measured and discussed is the cost of inaction or the cost of slower action, right. The cost of heat domes in the Northwest that kills 600 more people and normally would've died and the all sorts of costs. So, I wanna get you on this, yeah, it’s easy to talk about oh we can’t do that because it’ll cost X. Well, if we don’t do it, it cost Y, and Y is big and getting bigger?

Mike Fernandez: I think that’s right. I think from a broad analytical standpoint and even from a business and economic standpoint, there are costs always associated with change. There are very few times where you can get good fast cheap all in one. Oftentimes you have to choose two. And so, I think as a business person I buy into that. The question becomes what are the level of the costs that are borne by diverse communities. And then you get into the whole discussion around equity as well as looking at time to get to that amount of change that's necessary. You know what you hope is that you can look at an array of changes over some period of time that allows you to diminish the total of greenhouse gas emissions. I mean there are simple things --

Greg Dalton: Let me jump in here, Mike, and say does that mean, for example the Biden administration wants to look at overburdened communities and say if there is a refinery and then a plastics factory, we don’t want to put one more source of pollution. Do you support that kind of analysis that says, look, you know, these communities have been burdened, we shouldn't put one more source of pollution in them?

Mike Fernandez: Well, and I think you’ve got to look at each of those communities differently in the sense that sometimes the communities got built around them, as opposed to the industrial elements coming in after those communities were there. Places that people didn't necessarily want to live but they became, the less expensive places to live, because they were close to industrial communities. That's not right. We've got to find a way to deal with that. But where I was going with the analogy is on the other side is looking at the hopeful side to use Kelly's line that you know if we were able to blend you know, just 5% of hydrogen into natural gas. All of a sudden that reduces greenhouse gas emissions by 2%. There are lots of those kinds of things that can be done with current infrastructure with the current fossil fuel. That can play into this overall equation if we will enable that to happen.

Greg Dalton: Daniel Raimi.

Daniel Raimi: Just to this question of costs and benefits. I think we all know that there are costs to the energy transition. We all know that there are challenges and they are significant. But let’s put them in perspective. If you look at the cost of inaction, they by almost any accounting far outweigh the costs of swift action. For example, a study in 2018 that was published in the journal Science estimated that each additional degree of Celsius warming in the United States decreases U.S. GDP by 1.2%, right? That's hundreds of billions of dollars per degree centigrade and that's probably a lowball estimate. What's more, burning fossil fuels in the United States was recently estimated to cost 300,000 excess deaths here in the US. And so, we know that there are challenges of the transition, but we are almost certain across the economics and policy community that the damages from letting climate change continue at the pace that we are currently at is unacceptable.

Greg Dalton: Daniel Raimi, you've done research on orphaned oil and gas wells. We've been talking here about the need so do we stop building new ones. What we do with the existing and old ones. Whenever we do stop using oil pipelines what happens to them and who's responsible for cleaning up? I know that Enbridge has some of a plan for decommissioning Line 3 but Daniel Raimi what happens with this old dirty stuff as we get away from it?

Daniel Raimi: So, I can't speak to pipelines. I haven’t studied that but I can speak to oil and gas wells. There are roughly 2 million so-called abandoned wells in the United States. They're not being used for production or any other useful purpose. There are an estimated 1 million orphaned oil and gas wells. These are wells that are also not being used and we don't know who owns them. Most of those million wells we actually don't even know where they are. These wells risk polluting groundwater resources, they risk air pollution, they emit methane, which of course exacerbates the climate challenge and they can cost 75, 100, 200 sometimes even $1 million to clean up. And so, as we think about moving away from fossil fuels, we also need to make sure that companies are solvent and that they are able to pay for the cost of decommissioning this infrastructure, whether it's an oil and gas well or pipeline or a coal ash impoundment near a coal-fired power plant. And right now, the policies that are on the books are not sufficient to allow that to happen.

Greg Dalton: Mike Fernandez, is Enbridge going to clean up its massive pay for the pipelines once they’re --

Mike Fernandez: There is a process with pipelines both in Canada and the United States, where companies go through and meet with their federal regulator in terms of how they actually clean the pipes and how they cap them. There are remaining issues as to whether or not you actually leave the pipe in the ground after it has been cleaned or you pull it out and the considerations there is it’s sometimes there can be environmental risk by how the pipeline is pulled out.

Greg Dalton: As we get toward the end here I wanna think about what I've heard from all of you is that agree climate change is real. The transition needs to happen. There's some debate about how that happens and the speed that happens. What else do you the three of you agree on, do you think, as we come to the end?

Mike Fernandez: So, I agree with you. I agree all of those things are true. The question is, I think what amount of dislocation are we willing to tolerate as a society. This isn't an easy jump cut, you know, to move from fossil fuels over to wind, solar and other renewables. It really does require some level of transition and to be smart about it. And that's what we want to do. We want to think anew. We want to have those conversations around how do we best get there. But you don't get there by certainly just shutting things off.

Greg Dalton: Daniel Raimi, what do you think the three of you can agree on? There’s a transition needs to happen. There's disagreement on how and how fast.

Daniel Raimi: My hunch is that we would all agree on the notion that the energy transition needs to be equitable. We will probably disagree on some details about exactly what that means and how it gets done in the real world, but when I think about the energy transition and the need to dramatically reduce emissions, I think about the risk to some low-income consumers from higher energy prices. I think we would all agree that that's something to be avoided. I think we would also agree that the workers and communities that today rely upon fossil fuels for jobs for the tax base for other economic benefits need to have an equitable solution for them as well. Whether it’s coal-mining communities in Appalachia or oil-producing regions of West Texas, I think there needs to be investments made today so that communities can diversify their economies and succeed in a world where we're not using nearly as much coal, oil and gas.

Greg Dalton: Kelly Sheehan Martin.

Kelly Sheehan Martin: I think we agree that there needs to be a transition off of fossil fuels. I would like to hope we do. I think that we agree that there needs to be a minimized level of disruption. I would hope that we agree that we need to be investing in a world we wanna live in and stop pouring money in expenditures into the things of the past. And, I don't know that we agree about whose voices we listen to and I don’t know that we agree whether people who are most impacted by the climate crisis and whether clean water and clean air are more or less important than money. And that’s what makes me sad. And that makes me worry and keeps me up at night that we might not be able to solve the climate crisis in the time that’s needed.

Greg Dalton: Kelly Sheehan Martin is Senior Director of Energy Campaigns for the Sierra Club. Mike Fernandez is Senior Vice President of Public Affairs, Communications and Sustainability at Enbridge. And Daniel Raimi is a Fellow at the Resources for the Future in Washington DC. Thank you all for coming on Climate One today.

Mike Fernandez: Thank you, Greg.

Daniel Raimi: Thank you, Greg.

Kelly Sheehan Martin: Thanks so much.

Greg Dalton: On this Climate One... We’ve been talking about the fight over pipelines and where they fit into an energy transition. To hear more Climate One conversations, subscribe to our podcast on Apple, Spotify or wherever you get your pods. Talking about climate can be difficult--but it is critical to help advance awareness and understanding for positive change. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. It really does help advance the climate conversation. Brad Marshland is our senior producer; Ariana Brocious is our producer and audio editor. Our audio engineer is Arnav Gupta. Our team also includes Steve Fox, Kelli Pennington, and Tyler Reed. Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.