Community Resilience: Knowing Your Neighbor Could Save Your Life

Guests

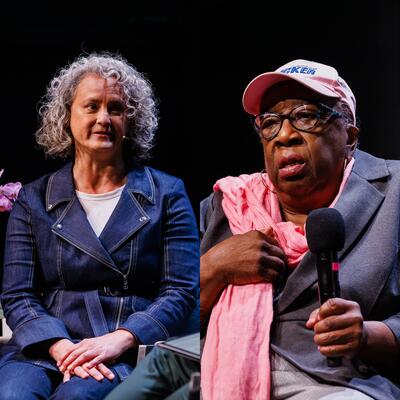

Tanya Gulliver-Garcia

Chenier "Klie" Kliebert

Amee Raval

Justin Hollander

Reverend Vernon K. Walker

Summary

Disasters caused by burning fossil fuels are becoming more frequent, and in the aftermath of hurricanes, floods and wildfires: federal and state responses are often slow or insufficient.

Meanwhile there is a growing body of research showing that neighborhood ties can be the difference between life and death. Reverend Vernon Walker, Climate Justice Program Director at Clean Water Action says, “ Neighbors that are socially connected are less likely to die from extreme heat. Neighbors that are socially isolated are more likely to perish because of extreme weather events.”

Building social connectedness depends on how people spend time in their neighborhoods. Justin Hollander, Professor of Urban and Environmental Policy Planning at Tufts University, asks, “Are you walking? Which is healthy. Are you meeting people while you're walking? That's healthy too. Are you in your car all the time? Not healthy.”

Mutual aid, where people within a community voluntarily exchange resources or services, can play a huge role in making a neighborhood more resilient. Tanya Gulliver Garcia, Director of Learning and Partnerships at the Center for Disaster Philanthropy, says, “Mutual aid groups are made up of people in the community. And all disasters start and end locally. Climate disasters – no different.”

Vulnerable groups like the LGBTQ community, and especially trans people, often have their needs overlooked when it comes to traditional disaster response. That’s a compounding problem in a political climate where their rights are being chipped away in many states.

One organization looking to serve the needs of those marginalized communities is Imagine Water Works – a New Orleans-based organization that facilitates mutual aid and climate preparedness. Executive Director Chenier Kliebert says mutual aid is rooted in solidarity and aims to increase the autonomy of individuals within a community. One of the ways Imagine Water Works is helping marginalized communities is by creating a disaster guide that applies to those specific communities. For example, of the LGBTQ community Kliebet says, ”We recommend that queer and trans folks evacuate more quickly if they can. We talk about the queer and trans experience and shelters just so folks know what they're getting into.”

The Asian Pacific Environmental Network recently released a report called Mapping Resilience, which aims to be a blueprint for understanding and mapping climate vulnerabilities to aid in disaster preparedness planning. Amee Raval, Research and Policy Director at the Asian Pacific Environmental Network, says tools like these are “incredibly powerful because in some ways it takes the principles of environmental justice, that working class communities of color are disproportionately impacted by adverse impacts from pollution, and operationalizes it via policymaking.”

In 2018 a project called the Communities Responding to Extreme Weather, or CREW, was started under the nonprofit The Better Future Project. The goal was to help prepare communities for floods and hurricanes. A year later, Reverend Vernon Walker became Program Manager of CREW and expanded their work into faith and underserved communities. Walker says, “I wanted to be very intentional about creating bridges to organizations that are working on other justice areas in hopes that we can not only forge an alliance, but form a relationship so we can support one another.”

Episode Highlights

4:12 - Tanya Gulliver Garcia on her experience with mutual aid

8:51 - Tanya Gulliver Garcia on mutual aid groups

16:01 - Chenier “Klie” Kliebert on the history of mutual aid

17:39 - Chenier “Klie” Kliebert on the Queer, Trans guide to hurricanes

21:58 - Amee Raval on community resilience

37:05 - Reverend Walker on his early work at CREW

41:11 - Justin Hollander on neighborhood vulnerability

43:43 - Reverend Walker on social resilience

47:42 - Justin Hollander on building better social connectedness

Resources From This Episode (6)

Full Transcript

Note: Transcripts are generated using a combination of automated software and human transcribers and may contain errors. Please check the actual audio before quoting it.

Greg Dalton: Disasters caused by burning fossil fuels are becoming more and more frequent. And traditional disaster responses don’t work in many neighborhoods.

Amee Raval: Dominant approaches of emergency management are failing many of our communities, especially immigrant and refugee communities

Greg Dalton: Actions like mutual aid can bring resources to people in their time of need.

Tanya Gulliver Garcia: We all need something. We all need help at some point in our lives. And so mutual aid is really about saying, Hey, what do you have to offer in a community?

Greg Dalton: Those community ties can be key to saving lives during emergencies.

Rev. Vernon Walker: Neighbors that are socially connected are less likely to die from extreme heat. Neighbors that are socially isolated are more likely to perish because of extreme weather events.

Greg Dalton: Community Resilience: Caring About Your Neighbor Could Save Your Life. Up next on Climate One.

Greg Dalton: There's a growing body of research that says your neighborhood ties might just be the difference in how you fare in a climate disaster. Socially connected neighbors are less likely to die from excessive heat or other extreme weather events. I'm Greg Dalton and this is Climate One.

Ariana Brocious: I'm Arianna Brocious. Greg, how often do you spend time connecting or talking with your neighbors?

Greg Dalton: I like my neighbors, and I actually spend a fair amount of time talking with them about preparing for wildfire and managing the groundwater that comes from our wells. Several years ago, we had a disaster drill and gathered at a nearby school thanks to a volunteer firefighter who got a government grant. How about you?

Ariana Brocious: Oh, I'm impressed that you did that. That's like really going above and beyond in terms of local organizing. I'm just starting to get to know my neighbors after a few years of living in this neighborhood. I really like the people I've gotten to know, and it feels nice to walk around and be able to wave and know who people are and their families, see people at the park. And it has had some climate related benefits too. A couple years ago, some folks came over and helped us do some rainwater harvesting project in our backyard. And just this summer, when we were having a lot of days of extreme heat, a couple people reached out and invited us to come over and swim in their pools, which sounds like a nice thing, kind of a small thing. But man, when it's 108 and you're trapped inside, It really makes a difference.

Greg Dalton: Oof, that sounds brutal. Yeah, we've had days to clear brush to kind of clear away fuel for wildfires. I have a tag near my door that I'll leave on my front gate so neighbors and the sheriff know we've evacuated if and when that big wildfire comes. We've actually seen fire helicopters flying over our house, delivering water to nearby fires. In short, we talk with each other in part because we know we're vulnerable and our fates are intertwined.

Ariana Brocious: And, you know, there's more data to show that though we need to be connected, we aren't. There's a report from the Surgeon General on the epidemic of loneliness in the U.S. that reports that one in two adults reported feeling loneliness before the COVID 19 pandemic. So you can imagine how that was compounded during the pandemic and in the years after. And so we really do need to build these community ties, both for our own well being and mental resilience, but then especially for climate resilience.

Greg Dalton: Vivek Murthy, the U. S. Surgeon General, so compelling and articulate on loneliness. People are becoming more and more isolated with friends on social media, but few meaningful friendships. I recently heard that referred to as the other A. I., artificial intimacy. At the same time, climate fuel disasters are becoming more and more frequent and intense, and that can sometimes trigger a response where we want to stockpile food, have water, maybe some guns, protect ourselves. That response, that isolation, is very different than reaching out and connecting with our neighbors.

Ariana Brocious: As you'll hear in today's episode, we should be building this community resilience, these ties, well before disaster strikes, because then you have those things in place when things happen. And it's surprising how often community action, this grassroots response, is overlooked when climate or other disaster happens. As we've seen in the aftermath of increasing floods and hurricanes and wildfires, federal and state responses are often slow, they can be insufficient, and they can also limit the resources based on someone's eligibility, which can exclude certain people from actually getting things that they need. So, some organizations, like the Asian Pacific Environmental Network, are using mapping to better understand what the community's vulnerabilities are before disaster strikes.

Greg Dalton: Right, and that thinking about bad things that you don't want to happen is really key, and those maps can help reduce disproportionate impacts. But regardless of your income level or degree of social connectedness, it does pay to organize with strategies that are often called mutual aid.

Ariana Brocious: Mutual aid is something that's been around forever, and it's had a resurgence in the years during the pandemic and after. To better understand this idea of mutual aid and other community resilience tactics, I spoke with Tania Gulliver Garcia, Director of Learning and Partnerships at the Center for Disaster Philanthropy. She's both given and received mutual aid.

Tanya Gulliver Garcia: I had a emergency where I was going to take custody of a family relative and needed to have a crib so that I could match the requirements from family services. And so I posted anonymously on a mutual aid list and said, does anybody have You know, a crib or a bed or something that I can put this child in and somebody made it available to me the next day. I was able to pick that up. It included, I mean, this is the most gorgeous crib I've ever seen in my life. It's better than my bed, I think. , but the mattress, the crib itself, the sheets, everything was there for me, all free of charge. And just because that family wanted to help out. with something they no longer needed.

Ariana Brocious: And that's a really lovely, lovely story. It sort of reminds me of the Freecycle groups that have kind of come up, similar concept. So how about you? Have you given mutual aid to others and what does that look like?

Tanya Gulliver Garcia: Yeah. I mean, FreeCycle is really a good example or a good comparison. It's just helping others in any way we can. So for two years after some of the big hurricanes that hit South Louisiana, actually organized a holiday program through Imagine Waterworks and it was. Mutual aid at its finest, because it was people giving, people receiving. So we signed families up who needed assistance for the holidays, getting gifts for their kids, both in Lake Charles area after the hurricanes there in 2020, and then in the New Orleans area in 2021. Families who needed gifts, didn't have money to donate, but sometimes they had objects to donate. So one mom donated a bicycle. Somebody donated a bunch of candy that they'd bought, actually with their food stamps, and so every child got a candy cane on top of their present. And then lots of the families volunteered to wrap the presents and deliver them. door to door. And so while there were people who had assets and wealth who were able to buy the gifts that were on a child's list or who were able to donate money so that I could go shopping for the children, everybody was able to benefit in some way at the ability that they had to give.

Ariana Brocious: It's like equal opportunity helping.

Tanya Gulliver Garcia: Yeah, we all need something. We all need help at some point in our lives. And we tend to think of communities that are in need as not having assets, not having any autonomy, any power. And so mutual aid is really about saying, Hey, what do you have to offer in a community? I grew up in a really rural community and to me, this is just what farm life and rural communities are like, or, you know, traditional Amish barn raising: When a neighbor's in need, everybody gets together and helps out. And then you pass it along.

Ariana Brocious: So what does this look like in our sort of modern age? You know, what, what does a mutual aid group tend to look like?

Tanya Gulliver Garcia: So we have a Facebook group with, I haven't seen the latest count, but at one point after some of the disasters, thousands of members, and you just put up a post as if you're making a Facebook post in any group and you title it in need of resource available, looking for, have to offer. So yesterday a young woman just got a job and she's looking for some work clothes. And so people were looking for things that they could find for her. Somebody else last week needed dog food. Um, and then when people have something to offer rather than selling it, going on another program or going into Facebook marketplace, they go into mutual aid and say, Hey, I have these assets. One of the most powerful ones for me a couple of years ago was after a tornado went through a community and a family said, Our house is a write off. We don't want to go back in there. It's going to get demolished in a couple of days. Doors are open. Here's the address. Go in and take whatever you need. The appliances are available. Anything that didn't get destroyed by the storm is yours for the taking.

Ariana Brocious: Wow. Yeah. And that actually, you know, then those things are also not just sitting in a landfill somewhere.

Tanya Gulliver Garcia: Absolutely. And especially in a disaster when we're already creating so much waste, right? We have, I think after Katrina, it was 30 years of landfill that was created just in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. And with each disaster, we just add to it.

Ariana Brocious: Can you explain why mutual aid responses fit in with the nature of climate fueled disasters particularly well?

Tanya Gulliver Garcia: Mutual aid groups are made up of people in the community. And all disasters start and end locally. Climate disasters, no different, it doesn't matter what's causing the disaster. It's going to begin with those, you know, the Cajun Navy type folks who are out door to door looking for people after a flood or after a hurricane. That's another form of mutual aid. So it's really the way that a community can take care of itself. FEMA might have one person on the ground. If they have somebody local that day or the next day, then they'll have a few more, but it's going to take a while for them to get stood up. And then the assistance that they provide is only based on the level of a disaster. So if there's a smaller disaster, what we call at the Center for Disaster Philanthropy, a low attention disaster, ones that don't get all of the media attention. And climate disasters definitely meet that a lot of the time. You know, they're smaller, they're those localized tornadoes or those local floods that go through, you know, rural farmland, but knock out hundreds of families. And so being able to provide that support means that your whole community is coming back stronger. And mutually it's also about organizing and getting people together. And so I think climate fits that really well. Black Panthers are an example of mutual aid. They set up the breakfast programs as a way to get kids fed. which gives them better results, but also to bring the parents in, to bring the caretakers in and to have those conversations about what does it look like if we organize and if we work together around educational reform or we work together around police violence. And so with climate, I think this is an example and an opportunity for us to gather folks and talk to them about the needs that exist in the work that needs to be done in climate and in climate justice. To, not necessarily solve, because I'm not sure if we're getting there yet, but at least to start some progress on making change.

Ariana Brocious: How does the work that you do at the Center for Disaster Philanthropy play into this?

Tanya Gulliver Garcia: One of the things that we look for at the Center for Disaster Philanthropy is those groups that are on the ground that are doing the work, whether that's a mutual aid organization or whether that's an established homeless shelter, violence shelter, mental health providers. And the majority of our grants go to local organizations. And so we have funded mutual aid organizations, including Imagine Waterworks, to respond to disasters, including COVID, hurricanes, and provide those resources. Most mutual aid groups are very small. It's a few people getting together, trying to organize, trying to do this work. Many of them are volunteers, but by giving them cash assistance, they can hire staff. After we made the first grant during COVID to Imagine Waterworks, that's when people started getting paid a salary for doing their work. And it also triggered other grant, other funders, to see, oh, here's an organization that CDP has granted to, let me also grant to them. And so they've become much more established now than they were. They have what we call the farm, and we're preparing right now for saltwater intrusion as this saltwater is making its way up the Mississippi

Ariana Brocious: Right, right, , slow moving disaster, which is different than maybe a hurricane or an extreme weather event that can hit suddenly, right?

Tanya Gulliver Garcia: And a lot of environmental disasters are slow moving, and they're hard to see, which I think also makes it hard to get attention for.

Ariana Brocious: So if someone wants to set up a mutual aid group or find their local group, , in advance of the next climate disaster for their area, what do you suggest they do? What are some of the principles to sort of keep in mind?

Tanya Gulliver Garcia: I think the most important principle is just the idea that everybody has something to offer and everybody has needs. I think a lot of funding generally, but especially in disasters, is what we call white saviourism, where somebody who's wealthier, whether it's the global north to the global south, whether it's individual, says, well, I'm going to help these poor people. And instead, mutual aid is about saying, no, everybody has those skills and assets. We just need to bring that out. So I would start with that point and then take a look around and see what's already happening in the community. I guarantee you that in bigger cities, there's something already happening. I mean, there's already organized mutual aid groups. In smaller communities, get a few people together, talk to your local faith communities, find out what their needs are and start small. You know, talk to the local shelters who are providing services, the, the wise and see, you know, what's needed, maybe adopt a school and, and start working with a school and have conversations because kids have assets too. There's lots of things that young people and youth could provide to a community as a whole and then receive other things in return.

Ariana Brocious: I love that idea. It's true. Everyone has something to give and everyone has needs. Tanya Gulliver Garcia is director of learning and partnerships with the Center for Disaster Philanthropy. Thank you so much for joining us on Climate One.

Tanya Gulliver Garcia: Thanks Ariana.

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation about community based climate resilience. If you missed a previous episode, or want to hear more of Climate One’s empowering conversations, subscribe to our podcast wherever you get your pods. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. You can do it right now on your device. You can also help by sending a link to this episode to a friend.

Coming up, how one organization created a disaster response guide for marginalized communities.

Klie Kliebert: We recommend that queer and trans folks evacuate more quickly if they can. We talk about the queer and trans experience in shelters just so folks know what they're getting into.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: Given the power dynamics in our society, some communities are often left out of the conversation when disaster planning is underway.

Ariana Brocious: Right. Vulnerable groups include the LGBTQ community, especially trans people in a political climate where their rights are being chipped away in many states.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, those hierarchies and marginalizations come through in times of stress.

Ariana Brocious: Imagine Water Works is a New Orleans-based organization that facilitates mutual aid and climate preparedness. Executive Director Chenier Kliebert says mutual aid is rooted in solidarity and aims to increase the autonomy of individuals within a community.

Klie Kliebert: it has a recorded history in Black and Creole communities dating back to the mid 1700s. Our organization, our staff are multi-generational Native New Orleanians, so we feel like we're really building on this legacy of our own people for, for so long.

Ariana Brocious: And in a world with increasing climate emergencies and disasters, mutual aid can respond faster and empower local people. It can remove hierarchies that exist in traditional disaster relief and meet the needs of communities who may be overlooked, like people of color or LGBTQ people. During the COVID pandemic, Imagine Water Works created the Trans Clippers Project, collecting and distributing hair clippers to trans people in need.

Klie Kliebert: We know that gender affirming care is overall great for people's mental health, but we also learned that cases of domestic violence were increasing during COVID, when people couldn't leave the house. they were maybe in a hostile environment and so as trans people especially were increasingly unable to present as their true identity, they were experiencing more violence in the home. We also heard from folks that they were getting increasingly misgendered when they were getting food deliveries and supplies deliveries, and so therefore they just sort of stopped accessing services.

Ariana Brocious: That awareness led to the organization creating other resources, like their Queer Trans Guide to Hurricanes.

Klie Kliebert: We, especially in New Orleans, are basically like the safe spot for queer and trans folks across the South. And so we have a lot of people moving in and out. It's also a pretty transient place. It always has been, and so we realized that our queer and trans community, especially, maybe didn't have this knowledge from multiple generations, but then also didn't have a place to go be safe during a storm.

Ariana Brocious: The guide includes practical tips and suggestions.

Klie Kliebert: We recommend that queer and trans folks evacuate more quickly if they can. We talk about the queer and trans experience in shelters just so folks know what they're getting into. And like a typical or traditional, maybe government sponsored guide, you would see some stuff to pack, but you wouldn't see things like chest binders and, tucking gaffs or makeup, again, if we're talking about how do you pass in an emergency. We talk about having documentation of your gender affirming surgeries, having your name changed documents, all that stuff doesn't usually appear in other materials.

Ariana Brocious: Imagine Water Works helps organize mutual aid to respond AFTER disasters too – like Hurricane Laura, which displaced 13,000 people from rural Louisiana into hotels across New Orleans. They figured out what people needed to feel more safe, comfortable and more human and made it happen.

Klie Kliebert: Slow cookers, microwaves. Similarly, also mini fridges were needed in that scenario, and that was to store medicine and breast milk, and that's stuff that the government isn't usually giving out. We had folks baking birthday cakes for people. hair clippers continue to be a thing.

Ariana Brocious: Kliebert says their mutual aid group has also helped change the culture around disaster response, specifically in the case of power outages. In response to Hurricane Zeta, they created a "Community Power Map" of people and places who will provide charging stations to anyone, creating a structure that local government has adopted.

Klie Kliebert: So our organization actually got some of the basic supplies to do that and offered that and sort of modeled what that could look like to folks and then we just gave it a structure, honestly. So when there's this idea of bubbling up in the public consciousness and then a structure is added to it, that allows it to be even more accessible to folks and actually just sort of gives people permission to do this thing that they had an idea about, that's when we've seen stuff really succeed. So, yeah, we did that and ended up having hundreds of people join, and then we talked to the city about ways to get them on board with the plan too. So we were able to get the city's fire stations on board, which then migrated over to the city's libraries. Which then migrated over to the recreational centers. And so now, several years later, the city has plans and a whole program in place to actually do that automatically. In that way, this grassroots mutual aid movement has influenced how the city of New Orleans, which is one of the most climate impacted places in the U.S., actually responds to disasters.

Ariana Brocious: Chenier Kliebert is executive director of Imagine Water Works in New Orleans.

Greg Dalton: Building neighborhood resilience is one of the best strategies for protecting frontline communities as climate disruption continues to fuel more disasters. The Asian Pacific Environmental Network released a report called Mapping Resilience, which aims to be a blueprint for understanding and mapping climate vulnerabilities and planning accordingly.

Ariana Brocious: Amee Raval is Research and Policy Director at the Asian Pacific Environmental Network, and she’s well-versed in the idea of community resilience.

Amee Raval: Building community resilience really means developing collective neighborhood based responses to crises. It means investing in social infrastructure, um, essentially which are the services and facilities that center the overall well being of the community. The social, economic, health and cultural well being of the community. And this is really distinct from traditional approaches that are either individual, privatized models for emergency response, which ultimately depend on how much money you have and whether you can afford your own air purifier or solar panels on your rooftop and battery storage. It's also very distinct from the way the state has focused its policymaking on climate adaptation.When it comes to climate resilience, policymakers are investing in mega infrastructure projects like hardening roads and bridges and protecting natural resources like forests and coasts. Achieving our vision for community resilience requires more than investing in that sort of utility scale infrastructure. It centers our neighborhoods and people, and ensures that their needs are being met to cope with and respond to crises as well as thrive in, in the everyday.

Ariana Brocious: One way I think about what you're describing is it's almost also taking advantage of resources that already exist in people's homes, in people's hearts, I mean, essentially making more of what we have together and unifying those resources, right, when, when faced with disaster or extreme weather.

Amee Raval: Yeah, I think that's absolutely right. And the pandemic, I think, is a great example of the ways communities really came together, whether that was schools providing food to family, mutual aid networks forming to share resources, um, during the heatwaves, Cooling centers being opened up at libraries. These are all really specific ways. Communities are showing up and these aren't sort of novel or newly constructed facilities or services. It's very much investing in trusted facilities. , And networks that already exist, , that can be deployed in those shock events, whether it is a heat wave or a power outage or, , you know, smoky days, which we're seeing worsening, but it's really investing in that existing social fabric and bolstering it through investments and resources.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah. So you authored a report called Mapping Resilience, A blueprint for thriving in the face of climate disasters that argues that climate risk is dependent on local and regional factors and mapping vulnerabilities through existing tools is a strong way to prepare for and build this resilience that we're talking about. What are the tools that exist now? And how do you use them to map vulnerability?

Amee Raval: So historically, the environmental justice advocates. Have spot lit and advocated for a tool called Cal EnviroScreen, which is readily used in policymaking to really target. The places most impacted by poverty and pollution for permitting for enforcement of pollution and for investments in climate mitigation and adaptation. That tool is incredibly powerful because in some ways it takes the principles of environmental justice, that working class communities of color are disproportionately impacted by adverse impacts from pollution, and operationalizes it via policymaking.

Ariana Brocious: And let's be clear for listeners that the CalEnviroScreen. That's a tool that's just in California, as the name indicates. There are similar tools in some other states. And the federal government is also working on an online mapping platform for climate risk and environmental justice. So let's just take one example, like help us understand what makes a community more vulnerable?

Amee Raval: We know that climate change is a threat multiplier. And so while climate change impacts everyone, the experience can feel dramatically different depending on who you are and where you live. In Oakland Chinatown, where my organization, the Asian Pacific Environmental Network, or APEN, organizes particularly Chinese immigrant communities, we see this play out. Oakland Chinatown in the Bay Area is a dense urban neighborhood. It's affected by the urban heat island effect. And many, , elders and working class families like those we organize and work alongside live in older, inefficient apartment buildings. Their homes can become a dangerous trap for people with respiratory sensitivities, especially on increasingly hot, smoky days. When the power goes out, seniors may not be able to leave their buildings without elevators, or preserve refrigerated medicine, or contact and reach loved ones for help. And especially, we organize monolingual elderly folks, they may not receive alerts or information about emergency conditions in language, specifically in Chinese. So these are just various elements that really speak to the types of indicators and factors we want to consider and layer in this type of vulnerability mapping.

Ariana Brocious: So what kinds of things are local government or emergency management groups doing based on the maps,

Amee Raval: We have a wide range of investments, whether it is solar and battery storage that energy commission sort of administers programs around whether it's tree planting or green space, whether it is, workforce development strategies or affordable housing development. These are just a few examples of the types of climate oriented event investments that are being made at the state level and various programs that utilize CalEnviroScreen as a targeting mechanism and many of those programs or types of investments that I named outline that at least 25 percent of that funding be targeted in disadvantaged communities defined by the CalEnviroScreen tool.

Ariana Brocious: Let's talk a bit about the work that your organization, APEN, does. First, I'm curious to know what specific strategies you use to help support these Asian immigrant refugee communities in the Bay Area, particularly preparing for extreme weather or disaster preparedness, but also just in day to day life.

Amee Raval: A fundamental part of our work at APEN, the Asian Pacific Environmental Network, is really ensuring that we're building community power and amplifying the voices of our members as decision makers for the programs and policies that impact their daily lives. That looks like a range of strategies. But I did want to uplift one that we've been really supporting our communities to envision locally, which are community resilience hubs. These are trusted places where people in the community gather or access services, not only during times of crisis, which they can be particularly equipped to respond to and provide supports around, but they're available every day to meet community needs as anchor community and cultural institutions in their neighborhoods.

Ariana Brocious: So one of those is the RYSE Youth Center, and I want to give people just a little context. This is in Richmond, which you can help explain, but it's home to the Chevron oil refinery and, and those fenceline communities. And so there are additional environmental justice concerns and, and fossil fuel impacts that exist in those communities before layering on climate disruption.

Amee Raval: That's right. Yeah. Richmond, California has been a refinery town since 1901 when Chevron opened what is now one of the state's biggest pollution sources, the Richmond Chevron refinery. Over the 20th century, Richmond became an industrial hub for the Bay Area with chemical plants, factories, and World War II era shipyards, , which brought a huge influx of Black workers to the city. And since the 1970s, more immigrants and refugees have made Richmond Their home due to its affordability. Um, and Richmond includes a large low ocean population, which is a community we've been organizing for many decades. For communities like ours, in the case of Richmond disasters like refinery fires, oil spills, power shut offs are a constant threat. Alongside those sort of Impacts from the fossil fuel extractive economy and the refinery. We also have other important And devastating crises. Our communities are experiencing like gun violence and the trauma from that.

Ariana Brocious: So how does the RYSE Youth Center and the work you all are doing there support the community in bringing additional resources or programming or strengthening community bonds so that in times of crisis there are people there to help?

Amee Raval: We brought together high school students, both from RYSE and APEN to essentially figure out what kinds of disasters people wanted to prepare for, what the resources they would need, and to envision a resilience hub that really serves the visions and desires of the community. They surveyed hundreds of their peers. And what we found is that they really wanted a resilience hub, not just for climate disasters, but also to also to cope with trauma from gun violence. That meant planning for solar panels and batteries and also centering healing spaces as part of the facility. They wanted to also be ready for refinery disasters and earthquakes. And one of the most important parts from that surveying was hearing that they wanted to make sure there were activities like art rooms, a meditative garden, sports and sort of a recording studio. A library is just a few examples of the ways that it is more than just a beautiful facility, but also has the robust and rich services and programming that makes it an inviting, thriving space. in times of crisis and also for the sake of support from a range of other daily impacts on conditions. Two weeks ago, we saw young people come together during a period of heavy wildfire smoke, um, and they distributed wildfire kits to their communities. And this spring we're actually planning to, um, practice emergency drills with RISE staff and youth in earthquake and refinery fire scenarios. So it's already being kind of deployed and explored as a way to, to build resilience across multiple crises.

Ariana Brocious: Beyond the work that you're doing in the Bay Area, are there more of these being developed and how could we support the development of more of these community resilience spaces?

Amee Raval: Yeah, I think really our approach was very much inspired by the work we saw across the country, especially on the East Coast. And so I do think this exchange across different communities around the country is happening. The concept is gaining a lot of momentum. Because I think we've seen the way traditional approaches just aren't working in a lot of communities across the country. The only climate disaster plan is to evacuate people too far away evacuation shelters like fairgrounds, places that people can't access without a car or are often run by sheriff's offices and maybe require people to show identification. So I think that momentum is really driven by the fact that across the board, dominant approaches of emergency management are failing many of our communities, especially immigrant and refugee communities like those we organize.

Ariana Brocious: Amee Raval is Policy and Research Director at the Asian Pacific Environmental Network. Thank you so much for joining us on Climate One.

Greg Dalton: Coming up, how having strong relationships with people around you can protect you when disaster comes to your town.

Justin Hollander: There's a pretty substantial body of research that tells us that the more people are socially connected there, the more resilient they are to these types of hazards and threats.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next. In 2018 a project called the Communities Responding to Extreme Weather, or CREW, was started under the nonprofit The Better Future Project. The goal was to help prepare communities for floods and hurricanes.

Ariana Brocious: A year later, Reverend Vernon Walker, became Program Manager of CREW and expanded their work into faith and underserved communities.

Greg Dalton: He also teamed up with researcher Justin Hollander, Professor of Urban and Environmental Policy Planning at Tufts University.

Ariana Brocious: I asked Reverend Walker and Justin Hollander to better understand how communities can respond better to climate disasters. Reverend Walker, who has since moved on to a position as Climate Justice Program Director at Clean Water Action, explained his early work at CREW.

Vernon Walker: Prior to entering into the environmental field, I did some organizing around racial justice and economic justice in the Boston area. And I wasn't seeing any climate organizations in those spaces. So what I wanted to do after transitioning to the environmental movement in 2019, I wanted to be very intentional about creating bridges to organizations that are working on other justice areas in hopes that we can. Not only forge an alliance, but form a relationship so we can support one another doing our justice work, because we know that climate change is not a single special interest issue alone, but it is rather multifaceted and it is complex.

Ariana Brocious: It's true that there's so much intersection with climate and all these other challenges that we're facing and many people in the climate movement think that we need to address them simultaneously. We can't just sort of fix climate or try to work on climate and let these other issues languish. So you spoke about building bridges with communities and that social connectedness. That’s kind of the focus of this episode. But the practical work that CREW has been doing, can you speak a bit about their activities like Climate Preparedness Week, creating cooling kits for people who are in urban heat islands, that kind of work? What does that do?

Vernon Walker: Yeah, so the Communities Responding to Extreme Weather just completed their climate prep week and climate prep week happens every year from since 2018, and it is a week that is focused on activities that raise climate awareness, that raise what climate change is, how it impacts the local neighborhood. So climate prep week was a main, hallmark, that crew leans into that crew does one of the other main hallmarks, is the interfaith summit, which happens during the spring where we bring faith communities together and we bring moral leaders and religious leaders and people of faith and people of goodwill together to talk about what does climate resilience mean in the different faith traditions, and how we can work together across different faith traditions to help create and build and promote more climate resilient communities. One of the other hallmarks of CREW is the summer engagement program, which revolves around distributing energy efficient air conditioning units and providing cooling kits to those that live in in neighborhoods that suffer from the urban heat island effect, and that started it really in 2020, we started distributing energy efficient air conditioner units to residents in Brockton and then it has involved and to. Distributing these energy efficient air conditioning units to communities in Boston that suffer from the urban heat island effect. We also partner with positions from Mass General Hospital to really conduct these workshops Where community members come for free and dinner is provided and we do a PowerPoint presentation of how climate change is connected to extreme heat and then we also show residents and attendees how the urban heat island effect impacts their community. And then we also the doctors come in at present how extreme heat affects the physical body, how heat strokes impact your body, how heat exhaustion impacts your body and what you can do to reverse if you're suffering from heat exhaustion. And then that's where the cooling kits would come in. Cooling kits have and electrolyte tablets, cool patches, thermometers, et cetera.

Ariana Brocious: Hmm. Yeah, what's really compelling to me about that is it's just sort of a grassroots initiative, it seems, to get people more ready for these increasing climate disasters and extreme weather that we've been experiencing. So the two of you helped author a study that looked at extreme weather and social connectedness in two vulnerable neighborhoods in Boston, and it builds on prior research from the Conservation Law Foundation. Justin, I want to get you in here. Why did you choose these neighborhoods to study? What makes them vulnerable to climate or extreme weather?

Justin Hollander: So the Conservation Law Foundation is a very prominent nonprofit organization that operates in Boston, and they authored this report that we were trying to build on in terms of looking at questions about social connectedness. Well, one of the things that they did was they look really closely at different Boston neighborhoods, and they rank them in terms of to what extent that each neighborhood is, is most, most vulnerable to environmental threats around extreme heat and flooding. And these two were close to the top of the list.

Ariana Brocious: And then what demographically makes them additionally vulnerable?

Justin Hollander: Yeah, so there were a lot of factors that Conservation Law Foundation used, and that, you know, in general, we use in social science research, which, you know, one would be linguistically isolated, and that is the case in the Chinatown neighborhood. You have a very high percentage of the population that doesn't speak English, and that, um, that really interferes with their ability to be able to access services and support in the face of emergencies. Another characteristic that, that was looked at in that report and, and we look at in general is income levels. people with lower income typically have fewer choices in their life and access to lower quality housing.

Ariana Brocious: What is social connectedness and how would you define it?

Justin Hollander: Yeah, so social connectedness is a kind of a big idea that has to do with how well people are integrated into their communities socially. And so when we kind of talk about the importance of responding to disasters or various types of hazards that people might face, there's a pretty substantial body of research that tells us that the more people are socially connected there, the more resilient they are to these types of hazards and threats. And so, so that's why we care about it.

Ariana Brocious: And Reverend Walker, you mentioned some of the initial work you did with CREW being around getting more intersectionality and kind of reaching communities that maybe before hadn't been as connected. How did you see that work integrating with this research study in this idea of social connectedness as it relates to the ability to respond to climate events.

Vernon Walker: Yes, social resilience is very important, and a lot of what informs CREW’s M. O. around building social resilience is what happened in Chicago in 1995. 739 people died because of a five day intensive heat wave, and there is a documentary out about what happened? There's also a book out, uh, published by Eric Klingenberg, And essentially the book that he published really emphasizes the idea that neighbors that are socially connected are less likely to die from extreme heat. Neighbors that are socially isolated are more likely to perish because of extreme weather events. And we know that climate change will bring. More extreme heat events, more floods and more hurricanes, et cetera. So that fell right in line with the work that I was doing at CREW, which was let's build up the social connections, and let's work with existing community organizations that have the community trust and that essentially our community anchoring institution, such as faith communities and libraries and community centers, et cetera. And then also what happened at those workshops is we also offered an opportunity for people to get to know each other, turn around and introduce yourself to your neighbor in hopes that social connectivity could be built.

Ariana Brocious: Yes, exactly, staying on that idea of building social connectedness. How does that relate to the role of faith in creating some of that social connectedness?

Vernon Walker: Oh, faith plays a big role. So I am a Christian and I strongly adhere to the Gospels of Jesus. And faith is a driving force on bridging the gaps between people, uh, because we are all tied in an inescapable garment of mutuality. And as Dr. King said, what affects one directly affects us all indirectly.

Ariana Brocious: So Justin, earlier this year, the U. S. Surgeon General called attention to the public health crisis of loneliness, isolation, and the lack of connection that exists currently in the country. He brought attention to this. That pre-existed the COVID 19 pandemic, but obviously was probably exacerbated by that. So how did that state of affairs show up in your study?

Justin Hollander: You know, a lot of the people that we talked to in our research had COVID, um, as the kind of context for these kind of questions about social connectedness. And so we decided actually that would be a good way to kind of do, uh, um, an introduction to our study. So we would ask people during COVID, who did you turn to, did you connect with your neighbors about COVID? Did you connect to the city? Non profit organizations? So we learned that people were quite familiar with the resources that were available to provide those kinds of supports around the pandemic. Um, so then we asked them about, what about extreme weather? And people, you know, largely did not, they, they didn't know what kind of resources were available and they, and they, for the most part, they didn't kind of Talk about like a same kind of rich network of a family and friends that they would go to it was more kind of Like a sense that they were kind of on their own. So so real a real interesting contrast

Ariana Brocious: We mentioned the Surgeon General's, uh, warning about isolation, and among his current priorities, Justin, is advancing social connection, and especially strengthening social infrastructure in local communities. And that spans a couple things, but it includes designing the built environment to promote social connection. And you've recently written a book called Buildings for People that talks about some of this. So how can the way we create and design cities build better social resilience and social connectedness?

Justin Hollander: You know, I feel like when you spend time in cities and towns and villages,how are you spending that time? Are you walking? Which is healthy. Are you meeting people while you're walking? That's healthy too. Are you in your car all the time? Not healthy. When we're not going someplace, maybe you're just at home. Are you going to like a local, local park? Are you hanging out in a plaza outside of some stores in a downtown? How are we spending our time has a lot to do with the shape of the built environment. You mentioned you live in Arizona. I mean, you know, they're Most parts of Arizona that I know are very car centric and have a very weak public realm. So it's the fact that you're discouraged from spending time outside, um, is going to make it less likely that you're going to connect with people.

Ariana Brocious: So Reverend Walker, one of the findings from your work is that simple things like neighborhood block parties are one strong mechanism for building more of this social connectedness. So tell me about how that effort is going in Cambridge.

Vernon Walker: So Cambridge actually offers 200, uh, for neighbors who are interested in organizing a block party, , and they will waive the fee to apply and also There will be provided a play street equipment, These kits can include equipment for climbing and bouncing cornhole giant parachute jump ropes, basketball hoops, street hockey, tether tennis, et cetera. And on, on the day of the block party, the city, play street team will transport the equipment and set it up. So when we talk about social connections and when we talk about building social connectivity, that's it right there. I think that could be a model for how to build social connectivity. And I think Cambridge is leading in that way. And there are other cities from what I understand across the country that have, that allows some funding to go out to for neighbors to organize, uh, block parties. A good result from that is that neighbors are building social connectivities that extend all year around, you know, New England is a place that is cold, figuratively and literally, it's not the South. It's not a lot of Southern hospitality in that sense where you walk down the street and people will just say, Hey, how you doing? I don’t, however, with the block party idea that Cambridge is leading on, it could help break up some of the coldness, in a figurative sense between neighbors where neighbors are actually working together to organize the block parties and also to get involved and get other neighbors involved. And I stopped by a block party this summer, here in Cambridge, and it was so great to see so much jubilation and joyfulness of people just connecting.

Vernon Walker: Thank you both so much for this really inspiring discussion about community resilience and climate resilience. Reverend Vernon K. Walker is Climate Justice Program Director with Clean Water Action, and Justin Hollander is a Professor of Urban and Environmental Policy Planning at Tufts University and author of Buildings for People.

Ariana Brocious: Thank you both so much for joining us on Climate One.

Justin Hollander: Thank you.

Vernon Walker: Thank you. So glad to be here.

Ariana Brocious: : That’s it for today’s show. You can keep these ideas moving. Reach out to your neighbor, or neighborhood association. Host a block party! And find out what you can do to make yourself and your community more resilient.

Greg Dalton: Climate One’s empowering conversations connect all aspects of the climate emergency. To hear more, subscribe wherever you get your pods.

Ariana Brocious: Talking about climate can be hard-- AND it’s critical to address the transitions we need to make in all parts of society. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. You can do it right now on your device. You can also help by sending a link to this episode to a friend.

Greg Dalton: Brad Marshland is our senior producer; Our managing director is Jenny Park. Ariana Brocious is co-host, editor and producer. Austin Colón is producer and editor. Megan Biscieglia is our production manager. Wency Shaida is our development manager, Ben Testani is our communications manager. Our theme music was composed by George Young. Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.