Greg Dalton: Welcome to Climate One, a conversation about America's energy, economy and environment. To understand any of them, you have to understand them all. I'm Greg Dalton.

Today, we're discussing skiing in the age of climate disruption. Rising temperatures are turning snow into slush, shrinking ski seasons and causing resorts to worry about their future. They're investing in energy efficiency and working to get off dirty coal power. They're also stepping into politics. More than 100 skiers have joined other companies in calling on the US government to adapt rules cutting the carbon pollution that could put them out of business. Over the next hour we’ll look at the meltdown in the mountains with our live audience at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco.

Our program today will be in two parts. First, we’ll hear from a scientist, a reporter and a professional snowboarder. In second segment, we’ll hear from the chiefs of the Aspen, Jackson Hole and Whistler Ski Resorts. First, the voice of science and ski enthusiast, and they can be both.

Porter Fox is Features Editor of POWDER Magazine and author of the new book

Deep: The Story of Skiing and the Future of Snow.

Anne Nolin is Professor of Geosciences and Hydroclimatology at Oregon State University. And

Jeremy Jones, Founder and CEO of Protect Our Winters and a professional snowboarder. Please welcome them to Climate One.

[Applause]

Anne Nolin, let's begin with you. Tell us about the recent snow trends, what science tells us about recent snowfalls and snowpack in North America.

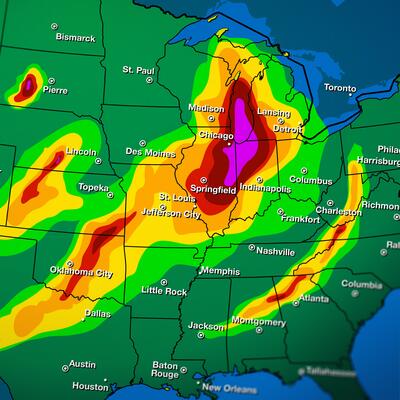

Anne Nolin: In North America we find that over the last several decades, there have been on the order of about 1.5 to 2 percent declines in snow in the spring per decade. So that means that the snow season is getting shorter. The lower elevations are getting hit hardest. They're having more rain on snow events, higher frequency of warm winters where you've got storm temperatures really close to zero where you can just kind of go from snow and shift a little bit right into rain. And so that has impacts on kind of the mom & pop ski areas that are situated in that lower elevation zone. And beyond that though, the hydrologic impacts, the impacts on water resources are also significant because you're getting rain runs off where a snow is that reservoir that holds that moister there until spring.

Greg Dalton: Right. So there are lots of water impacts but 1 to 2 percent a decade seems like — who would notice, right? Does that have much of an impact?

Anne Nolin: It does because if you think about the frequency of warm winters, and I define the warm winter as any month in the core winter months, December, January, February, where you have sort of an average temperature of zero or higher, meaning you're going to get rain, not every storm is going to be raining but nobody wants to come and show up at the lodge when there's drizzle going on. So if you look at today’s number of warm winters at ski areas, particularly in the Pacific Northwest where we have a lot of warm winters, maybe 30 to even 50 percent of some of these ski areas will have warm winters now. That's going to get pushed up to 70, 80 even 100 percent of the winters in 20 to 50 years with a 2-degree temperature increase. We could see a huge increase in the frequency of warm winters.

Greg Dalton: And you're talking two degrees Celsius?

Greg Dalton: Okay. So for Americans, that's somewhat changed.

Greg Dalton: Okay.

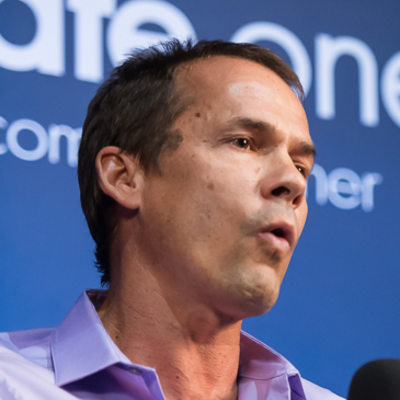

Porter Fox, you've been working at POWDER Magazine about 15 years. Have they noticed this 1 percent per decade? When did the climate reality kind of sink in there?

Porter Fox: I think they noticed that seasons were getting shorter on both ends, ending a little earlier in the spring, starting a little later in the fall. To be honest, we weren’t totally aware of the numbers before the last couple of years because it wasn’t really in the mainstream media in a way that got on our radar. So we’re going around doing ski stories and whatnot, noticing that there's less snow. And then when we started to look into it some more and read some of Anne’s work and see some of the studies that Protect Our Winters has done recently, we were shocked, everyone on the staff. I've been writing about skiing for 20 years. And I was totally surprised by the timeline and the quantity of snow that has already disappeared.

Greg Dalton: So you said the last couple of years. So Al Gore’s Inconvenient Truth came out six years ago. That didn’t register at all?

Porter Fox: It certainly did register but it was kind of in this large abstract realm of like “Hey, there's a meteorite that just went by the planet. Wow. That was kind of scary and close.” These are people, our demographic, and I can speak for myself and some of the editors I work with, it wasn’t in our backyard yet. It wasn’t something that was like “Oh, my God. This is changing my life right now.”

Greg Dalton: Polar bears in 2100, right?

Porter Fox: Exactly. It was really far off. And like the folks at the National Snow and Ice Data Center has spent some time there.

And they said snow and ice are this first visual indicator of how climate change is going to change our world. It is a visible polygon that shrinks and expands and it's shrinking very quickly right now. Disappearing sea ice first grabbed people’s attention, and then glaciers in Europe which have lost half of their volume in the last 50 years or last century approximately, and now it's starting to hit the US west, and now masses of people see changes in their backyard. You see grass growing on the slopes in Squaw Valley in January and you'd think “Well, this is a different world.” Looking at one winter is very dangerous in a world of climate change. We’re talking about decades and centuries but, still, that change is happening much faster than it ever has before the history of the planet.

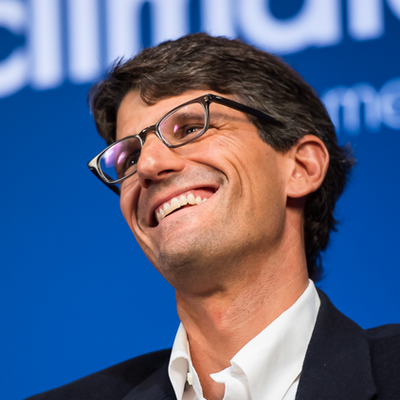

Greg Dalton: Jeremy Jones, when did you first notice this and what prompted you to start Protect Our Winters?

Jeremy Jones: I've been fortunate to spend my lifetime in the mountains. And I would say there are different indicators. Growing up on Cape Cod - I mean, first it was — growing up on Cape Cod, always wanting to snowboard and studying the pilgrims, harsh winters and going to my teacher, “Why don’t we have harsh winters anymore? I want to go snowboarding in the backyard.” So that was way ahead of Al Gore on that one [laughter]. But a couple of alarming things going to Europe — I spend time in Europe every year and just seeing — in Chamonix for example, you have this famous glacier that runs down the Valais Zermatt. It's a very well-traveled ski run and it ends and they built a train I think in 1920 to take it from the end of the glacier back to town.

And, Porter, you may not like — and then they built a chair lift to take you from the end of the glacier to the train to get back to town. And now it's an hour walk from the end of the glacier to get to the chair lift to get to the train. So that was alarming. But then as I started coming back or come back a year later and go “I used to be able to snowboard right here,” and to see this receding glacier — I mean, yes, glaciers recede a lot but not at that rate. So that was first kind of major shock. And then the second one was I was in British Columbia in Prince Rupert in February. And I was with a guy who was 30-years-old, and there was grass on the ground, and went for a hike up his whole mountain that no longer operates. And he's walking up the hill with his buddy and he's telling me about growing up on this hill and pointing out jumps, and he was just very positive and upbeat and proud to show me his resort. And I said, “Well, why isn't it open anymore?” He said, “Well, it just doesn’t snow here anymore.” That was a huge eye opener.

Here's a guy that's 30 who saw his home resort go away. And it started getting me thinking about climate change from a 30-year perspective and going wow — am I going to be at my home resort in 30 years going “Hey, kids, check out this grassy knoll that used to be the best jump on the mountain”? So those are two examples that motivated me to kind of reluctantly become an environmentalist because I realized that the mountains, for sure, were changing and that we have this…

I knew I had reached to skiers and snowboarders around the world in the media like POWDER that have been very receptive with protecting our winters. And I just felt like we need to come together and collectively protect our winters.

Greg Dalton: And how do you plan to do that? How does Protect Our Winters going to save the industry and save the snow?

Jeremy Jones: Well, one thing I didn’t realize when I started it was the complexities of climate change. Since I started it, I knew right away I needed to get the most educated scientists and voices and instrumental people as an example of that. But we have a couple of different facets, everything from focusing on — we have a Hot Planet/Cool Athlete program when we go into schools and educate kids on “Hey, this is the state of the climate. Here's a bunch of solutions. You're adapting this problem. Here are some tools to hopefully help to everything.” We were just at Capitol Hill trying to at least have the conversation on Capitol Hill. I'd love to say trying to pass climate legislation but we’re not even — we can't really have that conversation right now as a country. So we’re focused on the EPA’s rights to regulate emissions from power plants.

Greg Dalton: Anne Nolin, how do we know that humans are causing this? One percent variability of climate has been changing for hundreds of thousands of years. It's warming. What do you say to someone that says, “Well, science isn't clear. It's not settled. They’re not so sure that humans are causing the warming, these precipitation patterns”?

Anne Nolin: Well, surfacing that the science is clear and there are multiple lines of evidence that climate is changing and that humans are responsible for it, but I think perhaps the most convincing line of evidence is when you look at the type of carbon that's put into the atmosphere, we know that it's coming from burning fossil fuels. That's something that humans are responsible for. And then when you go through the physics and incorporate that into a climate model and simulate and diagnose exactly how that increase in carbon dioxide then warms our atmosphere in the surface of our planet, we see that even though there are multiple forcings like multiple factors that are responsible for changes in climate like solar radiation, for instance, or volcanic eruptions, carbon dioxide is the number one forcing factor, the driving factor, and that is entirely due to humans.

Humans burn fossil fuels releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, and that carbon dioxide from human impact is responsible directly for the warming. And if you run computer models, the climate simulations without carbon dioxide, you can't even come close to matching the actual measurements of temperature. The only way you can get models to fit what's really happening is by putting CO2 into the model. So we know diagnostically, using those models that you have to have CO2 as that forcing factor. And we know from our measurements that the CO2 is coming from human impacts. So those two lines of evidence together show that climate change is real and it's caused by people.

Greg Dalton: And looking forward, are there certain regions that are more vulnerable than others? Are the Rockies going to be okay because they're and the northwest got some problems? Is science that precise that can tell you about regions and perhaps even state some resorts?

Anne Nolin: Well, if you're looking at it from a mountain perspective, there are certainly regions that are more vulnerable than others. And I would say the lower elevations are more vulnerable for snow. The arctic on a global scale is more vulnerable than, say, the mid latitudes. And we've seen significant increases in temperature and declines in seasonal snowpack in arctic. In fact, the arctic has lost more seasonable snowpack more rapidly — the declines in seasonal snowpack in the arctic had been more rapid than the declines in sea ice in the arctic.

But back to mountains though, the big vulnerable areas in terms of snowpack or the lower elevations where it's at risk of turning into rain. But I'd like to challenge us to think about mountains more broadly, not just as first world destinations resorts. Mountains are places. They're not just flat areas up high. They are places where you have steep vertical gradients of climate, of biodiversity and gradients of hydrology. I always say that water and ecosystem services flow down from the mountains but people that live down in the lowlands and it's the policies of humans and our demographic pressures that flow uphill and cause this raged, somewhat isolated mountain environments and mountain people to be at risk. So we got at risk snow but we also have at risk social environmental systems in the mountain environments. So most mountain environments are places where people, communities tend to be more marginalized. The populations don’t have economic clout, they don’t have political clout, they don’t have access to productive lands necessarily. So it's a really — so they're facing challenges not just from climate but also from human impacts due to policy and demographic pressures.

Greg Dalton: So there are bigger impacts things here than sport and recreation, a lot at stake for people’s livelihoods.

Greg Dalton: Okay.

Porter Fox, you've been driving around, writing in series in POWDER Magazine, the future of snow. Tell us about some of the things you saw. The reaction of people there is like “It ain’t happening. It's not us.” There was a politician in Montana you wrote about that basically said. “Global warming is going to be good for Montana. We could use some more warmth up here. Thank you very much.”

Porter Fox: Montana also has a fairly large fossil fuel industry going there. And ironically, a lot of the ski area states in the west do, as well as Wyoming. What I saw was a full range. I was impressed with the people that I met in the western US who were very open minded because they were seeing it. I spoke with patrollers, avalanche experts, people who had lived in the mountains for over 50 years and they said, “Yes, I don’t get snow in my yard anymore.” It doesn’t get down to 35 below anymore, and certainly not more for — not more than a day or two. This is empirical evidence that these people had seen. And 30 years is way better evidence than four or five years that a ski bum is like “Oh, it's not snowing anymore.” This is way bigger than skiing. Skiing is a recreational sport. It's something I've done since I was two-years-old and something that is very dear to me. But this is about snow as a part of the climate cycle on the planet and part of the water cycle, and an incredibly important resource on earth that when snow starts to disappear, there is this line of dominoes that falls down that people have seen out in the western US already with the wildfires and the pine beetles and all of these things that kind of come from a lack of snowpack and a lack of steady water supply.

Snow is a natural water storage. So people saw the effects. They were still trying to get their heads around the fact that humans can change things on that scale. This is a very difficult thing for people to understand. It's hard for me to understand but I would believe 1,000 climate scientists who studied 2 million gigabytes of data and over 1,200 peer-reviewed studies. I would believe them before I would believe someone that says, “Yes, I don’t think this is happening.” The same way that I would believe someone that said, “Killer meteorite is coming for your planet.” I don’t think anybody would doubt that scientist or doubt a doctor that says, “I'm sorry but you've got cancer.” You don’t say, “I don’t think.” You might get a second opinion but you're not going to be like “Yes. Whatever. I'm going back to my life.”

Greg Dalton: Porter Fox is a features editor of POWDER Magazine. We’re talking about the future of skiing at Climate One at the Commonwealth Club. Our other guests today are

Anne Nolin, Professor from Oregon State University, and

Jeremy Jones, Founder of Protect Our Winters. I'm Greg Dalton.

Anne Nolin,

Porter Fox mentioned fires. There have been a lot of fires in ski areas. Sun Valley was threatened by fires. There are fires in the Sierras, terrible fires in Colorado. How does that impact water and the hydrology cycle in mountains and perhaps ski resorts?

Anne Nolin: There's a really strong relationship between fire and snow. What we see is that when snowpacks decline, the forests themselves which depend on that snow become moisture stressed. And moisture stressed forests are a lot more vulnerable to things like pine beetle and wildfire. And once the fires burn through the forest, especially if it's a really severe fire, the subsequent years, the snow melts off faster in burned areas.

So maybe this isn't a big deal. Well, it turns out it is. In the last ten years, there have been over 44,000 square kilometers of burned areas in the seasonal snow zone in the western US, and a disproportionate amount of that has been in the Columbia River basin. So if you think about, okay, the snow is melting faster in these burned areas, these are all the headwaters of these rivers, that means that that snow is no longer being stored there. It's flowing earlier so you might have higher peek flows and then ultimately lower low flows in the dry time of the year. And so fire and snow and water in the streams are all intricately related, it's all linked.

Greg Dalton: If you're just joining us, there are many podcast in the Climate One’s section and iTunes that focuses on the impact of declining snowpacks on the Bay Delta in California and other water at climate impacts.

Jeremy Jones, I'd like to ask you. Given your concern about climate change, what do you think about helicopter skiing and burning fossil fuels to get to cool places that are hard to get to? Is that something you still do?

Jeremy Jones: I mean, on a personal level, I look at my whole carbon footprint, I continue to reduce where I can but still living my life. With that, 10 years ago, I used to spend probably 20, 30 days in a helicopter. About six years ago, I stopped using helicopters to access the mountains. I look at my helicopter consumption as just rate in line with the car I'm driving, the food I'm buying, every aspect of that with my snowboarding.

I am a professional snowboarder. I still travel. I've always traveled. I've kind of grown up as a traveler. I feel like I've learned a lot from travel but these days — I'd say eight years ago I used to chase the snow ten days here, seven days here, four days here. Now I'm doing one to two-month long trips. So kind of getting more bang for my buck. If I am hopping on an airplane, I try and make it last to spend much more time at a place.

Greg Dalton: Anne Nolin, what are you doing to manage your personal carbon footprint?

Anne Nolin: I walk and I ride my bike. My family and I made a decision to live near our work. And I jokingly say I walk. My commute is actually just a three-minute walking commute but we really did design our lives so that we didn’t have to walk — so that we didn't have to drive, I should say, to go out to eat or we don’t have to drive to commute. We can ride our bikes to the grocery store. And we are showing our son that that's a way to live. And we’re lucky enough to live in a community in Corvallis, Oregon where we can do that. And there are loads of bike pass, and it's really easy to ride a bike even though it rains a lot in the winter. So that's what we do.

Greg Dalton: Porter Fox, what are you doing and what kind of other average citizens listening to this do to reduce their carbon impact that's impacting the snow industry?

Porter Fox: Mobility is a big thing. Mobility is independent especially for Americans and our history with cars. I burn veggie oil in my diesel station wagon. As anybody who’s ever ridden with me will tell you it breaks down a lot.

And we compost our vegetables. We have a garden in the back. I live in Brooklyn, New York. I have to ride the subway. I took a plane out here. That is the structure of our world right now and this is a transition. This is not a cut cold turkey. And people can look up — they can go to POW’s website and look at the seven steps for the POW pledge and see what they can do…

Greg Dalton: POW is Protect Our Winters.

Porter Fox: Protect Our Winters, yes. Things like — if everybody in New York change their light bulbs to CFLs, you could run the subway off of the — electricity savings. There are very simple things that we can do. They say 15 to 20 percent of the first steps in conserving energy is very easy to do. You walk to the store instead of driving. It's the next 20 percent that is very, very difficult. Now you're not going on vacation to the Bahamas because you can't afford to burn that fuel in the plane to get down there. And that’s when you're starting to take people’s rights away. The first 20 percent, we can do that, but the position that we are in right now, it is going to take far more than that to avoid going above the 2 degrees Celsius safety threshold.

Greg Dalton: We’re talking about skiing and snow at Climate One. I would like to invite your participation. We’re going to put a microphone out here and invite your comments. The line will start with our producer, Jane Ann, over there. So the mic will come out now. Oh, it's there. And if you're on this side, we invite you to come over through that door over there rather than crossing these camera lines. And this is often one of the most vibrant interactive parts of the conversation.

All these skiers and no one is jumping up. This is crazy. Let's include our audience questions. Welcome to Climate One.

Participant 1: Hi. Thanks. Anne, can you just talk about the Sierras a little closer to home. Anything you can tell us about the future of snow in the Sierras?

Anne Nolin: Well, what we found is that if you look at the frequency of warm winters and what I call at risk snow which is snow that's at risk of falling as rain, the lower elevation resorts are likely going to have significant negative impacts. And even places like Squaw Valley are likely to have almost a doubling in the number of warm winters with a 2 degrees Celsius warming.

Greg Dalton: How about timeframes? Think about children growing up now. Do you still teach your kid to ski? Are they still going to be able to — is it going to be around? Do we know timeframes? I know that you're discipline,

Anne Nolin, often thinks about decades or centuries, right? So it's hard to say 10, 20 years you'd like to have a few centuries to work long time scales, longer than humans are used to. Do we really know?

Anne Nolin: It's interesting. We always think of climate change as something that's going to happen in the future but I look at it as something that's already been happening. So for instance, one of the sites that we've been looking at in Oregon where they've been — people have been going out manually measuring the snowpack every month since 1941. We see 70 percent decline in 70 years in the peek snowpack at that elevation. So it's not — when you talk about timeframe, I don’t know how fast that's going to happen but for every 1 degree Celsius increase in temperature, the snow line increases vertically, about 150 meters, so triple that and add a little bit for feet.

And so when we think about maybe by mid century that we would see about maybe a degree increase in temperature, but it's going to vary by region, areas that are close to the coast and already pretty warm, even half a degree increase, you're going to see huge impacts, a big switch from snow to rain. So it really depends on how close you are to that melting threshold.

Porter Fox: And there are a few modelers who have kind of stuck their necks out and put a number on this like Daniel Scott’s work at the University of Waterloo in Ontario. And they've been studying climate change and its effect on skiing since the 1980’s. And he authored the paper that suggested that in the next 30 years, half of the 103 ski resorts in the northeast will have to close because of lack of snow reliability. That's a radical change. And that is, in our lifetimes, some of our lifetimes and definitely our kids’ lifetimes.

Greg Dalton: And in that report, he said that no viable ski resorts in Massachusetts or Connecticut and certainly a shrinking in New York and New Hampshire. Let's have our next audience question. Welcome.

Participant 2: Yes. First, I just have a comment. I like that first 20 percent is very doable, and I think that's what we’re working on. And I just noticed an article today that actually states that US carbon dioxide emissions dropped last year. That's fabulous. So obviously, we’re paying attention to this 20 percent. People are starting to get it. So give me some good new. I mean, you just told me we’re going to close all these resorts. I've been skiing for 55 years, and I see it. My question is, all right, we are starting the path. We’re doing our 20 percent the first. Is this going to affect — am I going to see snow coming back or is this just a battle that we’re going to always fight?

Greg Dalton: Anne Nolin, are we just slowing the rate of decline or is it a turnaround story?

Anne Nolin: I'm afraid to say, it's slowing the rate of decline. Carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is a long-lived gas. We should have been doing this 50 years ago. And it's great that we’re doing it now because it's going to help the next generation and the generation after that. Climate change is the biggest challenge of this generation and the next. And we absolutely should be making that change now.

Greg Dalton: And there are a lot of positive stories out there about fantastic technologies that are happening, a lot of progress organizations people are creating. There is some light in this as we go down this downward slope. There's definitely some sunshine. Let's have out audience question. Welcome.

Participant 3: Thank you. So I think we all know it's a pretty complex problem. And I think it's great that we have representation from public, private and nonprofit on the stage right now. And I'm wondering if any of you have any thoughts on either the greatest opportunities for cross-sectoral collaboration or the greatest challenges that are limiting that from really helping progress things forward. I think it's great that the flyer includes the POW collaboration with the Mountain Collective. So hopefully it's something that you thought about a little bit.

Greg Dalton: Who would like to tackle that one? We got about five minutes left.

Jeremy Jones: I would say it's — I've been, since 2007, definitely been — had my hands in this. And I think it's a subtle step here. And I think we have Aspen who’s definitely been on the forefront of sounding the alarm and accepting what the future holds. But I think it's a huge step from a resort perspective to have the resorts that are here today to speak on this matter. I think it's maybe the first time or one of the first times that we've had a collection of the world’s best resorts come and speak on these matters.

So it's huge step forward just to — that we’re having this conversation with the top resorts.

Greg Dalton: Jeremy Jones is founder of Protect Our Winters. Let's have our next question. Welcome.

Participant 4: Thanks. As a snowboarder, what can I do to tell my favorite ski area that I care about climate change?

Jeremy Jones: Well, I think you should ask that question to the second group of panels because you'll hear it from the head honchos how your voice could be heard the best. But I think the comment box is using your voice. And that's one thing we've learned with Protect our Winters is we've gotten more active with op-ed pieces and just being more vocal about the issue and getting it out in the media because it's still the power of your voice. And the media outlets, it is effective and it does trickle up to the head honchos if they hear it from enough people.

Greg Dalton: Let's have our next question. Welcome to Climate One.

Participant 5: Thanks. I guess I had a question for Porter and Jeremy. I guess given the unique audience, maybe of skiers and snowboarders, do you think there's a specific opportunity there to reach out to this demographic to make a change that maybe is different from other — there's a lot of groups out there trying to work on climate change and legislation and influence people.

Porter Fox: I think, absolutely. This is very influential demographic. I mean, let's face it, skiing was the sport of the leisure class from the very beginning. These are people who are influencers. They have contacts and big government, big business.

The idea here, once again, is yes, we want to save skiing but we want skiers to literally help save the world. And that's what we’re going for. That's what Protect Our Winters has been doing for a long time now by taking the collective voice of the skiing industry and skiers and taking that to Washington and saying, “Hey, this is really important, and you guys need to listen to us.” And they listen to them. And they have done incredible work, especially recently, just building up to Obama’s climate action plan. I mean, that was — he didn’t mention that there was melting snow and ice in the mountains and everybody downstream in there should be worried just because he felt like saying that. That was the message straight from POW and straight from the ski areas that — the 108 ski areas that signed the climate change declaration, which was fantastic. Some of them are here tonight. So it's a great demographic and a very powerful one if we can come together.

Greg Dalton: Let's have our next question for this segment. Yes. Welcome.

Participant 6: Hi. Thank you. I think it's really exciting to see — I've been following climate change forever, I guess, since I was in high school or middle school. But the elfin in the room are countries like China and India, tons of people, tons of emissions, you could say, that are kind of going through what we went through in the colonial revolution. So how do you guys think emissions from China and more developing countries can be controlled if they're giving such a large proportion of what's going on in the world, the global system?

Greg Dalton: Anne Nolin, let's have you answer that and then we’ll get to the second segment. Whatever we can do, feel good about; China can blow it all the way. [Laughter]

Anne Nolin: I wish I could answer that question. I'm not an expert in policy and I feel like, okay, well, if we all start driving electric cars in China and start sequestering carbon then we can fix this.

Carbon dioxide is a pollutant. And China has a pollution problem and they need to address that first and foremost. I mean, that's an immediate health problem of just monumental level. So I think it's really related. I apologize but I really can't speak to that policy issue but I think it's really significant and we need to keep thinking about it and be more imaginative but it's a really broad problem.

Greg Dalton: We need to wrap this part up and then we’re going to have another group of guest come up in here and join us. We’re talking at Climate One about the snow and the future of skiing. Our guests on this segment had been

Jeremy Jones, Founder and CEO of Protect Our Winters,

Anne Nolin, Professor of Geosciences and Hydroclimatology at Oregon State University, and

Porter Fox, Features Editor at POWDER Magazine. Thank you all for coming. And let's give them a round of applause. Thank you very much.

[Applause]

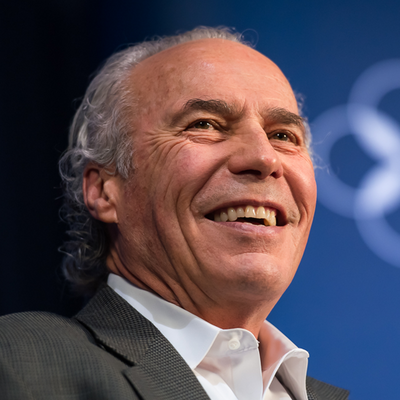

We’re talking about the future of the skiing at Climate One. We’re joined now by the heads of three destination ski resorts.

Jerry Blann is President of the Jackson Hole Mountain Resort in Wyoming. Dave Brownlie is President and CEO of Whistler Blackcomb in British Columbia. And

Mike Kaplan, President and CEO of Aspen Snowmass in Colorado. Please welcome them at Climate One.

[Applause]

Welcome gentlemen. Let's start, Dave Brownlie, with you. How would you characterize the health of the ski industry? We just heard about declining snowpack, et cetera. How is the health of the industry right now?

Dave Brownlie: Actually the overall health of the industry is actually really strong, what we see out there and certainly in North America and in Europe. But if you look at, actually, the last 10 years in North America, you see, actually, increasing revenues, increasing investment in the sport. We've come off two of our tougher years over the last couple of years, and it's actually been very resilient as we go forward.

So we actually are very positive about our industry. And we think we’re going to continue to be a very positive enterprise in business well into the future.

Greg Dalton: Mike Kaplan, a lot of the ski travel in the United States is headed towards the Rocky Mountains. And resorts are doing a lot to reduce their energy impact but a lot of the impact is really the flight there. So what is being done to — and that's outside your direct control but destination in skiing, you can do recycling and sorts of things but it's that flight there — a lot of people go to Aspen Snowmass with private jets. So let's talk about that aspect of the impact.

Mike Kaplan: From our standpoint, I'd say the biggest opportunity is to talk to people about those impacts. You happen to be flying to Aspen to come on vacation or you're flying to somewhere else to go visit kids or whatever it is. So rather than view it as “Oh, don’t come here because you're having an impact in the environment,” we see there's an opportunity to say, “You know what? Come here, enjoy the snow and think about it for a second. Do you want to enjoy that snow for years into the future? Do you want to enjoy that snow with your kids?” So we take it as an opportunity to say, “Guess what? There’s a connection between flying out here, your carbon footprint and things you do everyday, and the things you like to enjoy doing with your discretionary dollars and discretionary time.” So we view it as an opportunity to educate and hopefully influence and get them to act their way around “Hey, we need to do something about this.”

Greg Dalton: Jerry Blann, one thing that resorts are doing is making snow. Snow is declining. Resorts are investing a lot in snowmaking technology, which involves using water, a scarce resource, and typically burning some fossil fuels, which makes it worse.

So talk about the irony of snowmaking as a response to declining snow.

Jerry Blann: Well, it's become, honestly, a mitigation to some of the things we’re talking about here this evening. As time goes on, certainly temperatures come down. We have had to respond as an industry to that change, and in doing so, snowmaking in particular, the technology, along with that has evolved along with that. Lower energy guns, the less use of compressed air onboard computers, technology that really make the most efficient use of the snowmaking.

And you're right, it's water. We happen to store it on the mountains and recycle it. And there's been a lot of analysis on that matter. I think we’re getting better at it in terms of the conversion of that. In the case of Jackson, we always used to be known as the too far, too cold and too steep. And some of that is being mitigated as part of this discussion not in the proper way, but having said that, it has changed. And in our case, we have primary routes off the mountain only with snowmaking. You generally get snow in the upper mountains, and that is the benefit it does very nicely, and it's worked. Now as time goes on, hopefully we’re able to hold to that.

Greg Dalton: I'd like to talk about something called the climate declaration. And I'd like to ask — these are a group of companies that stepped up and said, “We want the US government to do something.” So

Mike Kaplan, why did you join that and what do you hope will come of that, joining other companies saying, “Hey, Washington, get on it”?

Mike Kaplan: If you really stop and think how do we solve this problem, I think the prior panel talked about, the first 20 percent is I wouldn't say easy but it's doable through efficiency and some of those other things.

But to really tackle this problem at scale, you've got to have government scale approaches to this. And if you're going to allow carbon emissions to be free, you can emit carbon with no cost to that externality. In the end nobody is really going to do anything. They're not going to do enough to tackle this at scale. So as you start to think about that and think about “Okay. How are we going to really get there?” acting alone isn't enough. And so we signed on to this because it's a collective effort because we think collectively, we have a stronger voice, and can hopefully spur government and President Obama and those leaders into action such that you can get results at scale.

Greg Dalton: And you also — Aspen Snowmass was actively engaged in the state of Colorado and went after coal. So tell us about that.

Mike Kaplan: As we've looked at our own footprint — we need to walk the talk. We need to address our carbon emissions, our consumption. Like most companies, I think like the planet, about half of our emissions come from really buildings and our consumption of electricity. And so as we look at that, we say, “Well, again, we can change light bulbs,” but what happens when you're done changing light bulbs? We banned incandescent light bulbs, right? So what else is there? You got to look downstream. Where is our power coming from? It's coming from coal. And as we look at our carbon emissions, there's that direct connection. So we got active in state legislature to increase the regulation of the utilities, to force them, drive them; encourage them to reduce their emissions. And that's been successful and we’re going to continue to push on that.

Greg Dalton: You're going to weigh into the fracking debate? That's the hot one.

Mike Kaplan: No but we’re looking forward to the science coming out and what are the true emissions associated from the source all the way to delivery. Is that truly a bridge feel or not? We encourage, again, some transparency on fracking fuels and those types of things so we can make sure it is moving us forward and reducing overall emissions.

Greg Dalton: Jerry Blann, Wyoming, big energy state, big coal state. The family owners of Jackson Ski Resort actually used to be in the coal business. Do you have a similar posture as Aspen Snowmass on coal or are you taking a little different path?

Jerry Blann: I knew I was going to get setup [laughter]. Wyoming is the biggest coal producer in the country. It's the largest oil and gas producer but it's also the 11th most renewable resources development within the states. So we produce a lot more energy than we consume by far, all 560,000 residents in the state of Wyoming. So no question.

We are conflicted to some degree. But having said that, being on the edge of the largest ecosystem, meaning the Yellow Stone ecosystem, our community in the northwestern part of the state is very cognizant of the challenge that we face. And I would tell you that our congressional delegation is a swell. They certainly get lobbied on both sides of that with the GDP in the state of Wyoming being 30 percent in related energy. There's no question what is driving. Tourism is the second largest industry but I would tell you it's a big step now. So we are challenged with that. Our congressional delegation understands where we’re coming from basically as well. And they do come to Jackson and ski. So with the challenges that are represented as part of that, the whole idea is balance and how do you get there in the most efficient way. We do that through a number of different ways.

We have very segmented steps and challenges along the way that we've attempted to set. We actually have a step down from ‘95 to 2015 of a 10 percent reduction in our overall energy usage, set to a specific criteria in terms of the number of business but it's not easy challenge. And I think — as an industry, I think we've done a pretty good job on the efficiency piece. Have we done a very good on the advocacy piece? Mike and his team in Aspen had certainly led the way on that.

Greg Dalton: We've had Auden Schendler here, your sustainability VP has been here at the Commonwealth Club before. Dave Brownlie, you're in Canada, British Columbia, where there's a price on carbon pollution. It's not free as

Mike Kaplan said earlier. How has that affected the economy in British Columbia and how has that affected Whistler Blackcomb?

Dave Brownlie: There is a carbon tax and it's a carbon tax on fossil fuel usage, gasoline and diesel. And there's certainly controversy surrounding when it was enacted but the reality is that province has accepted it and it continues on today. The economy continues to be robust where people are paying more for their use of gasoline and diesel today. So yes, we continue — we’re certainly proactive as a province. We’re all trying to do our part in terms of what we can do make a difference but as every said, it is a big challenge.

Greg Dalton: So what’s the path from here? Let's ask

Mike Kaplan. Is this industry going to be shrink? One report predicted that only 4 of the 14 top ski resorts would be viable in 2100. What's at stake in terms of jobs and communities if this is going to be a shrinking area of the economy?

Mike Kaplan: The stakes are significant in terms of the communities that are dependent on tourism. I think the industry is engaged in adaptation in a serious way both in terms of efficiency on snowmaking, as Jerry mentioned, but also in terms of offering experiences to guests on a year round basis.

So Whistler has led the way in developing summer business, specifically on the mountain biking side and sightseeing and all kinds of incredible things going on. We’re all seeing that. I can tell you, we did have a couple of tough years. We were really waiting for it to start snowing again.

And it was a relief to get in the summer season where, guest what, we’re going to spin those lifts either way because we’re going to have our mountain bike trails open. We’re not waiting for it to get enough snow on them.

So I think there is a lot of that going on. So it's making the most of what we have in a sustainable way, and also, again, adapting to what Mother Nature is providing which, at the end of the day, is what I would say mountain people are all about. We’re used to having to adapt to whatever Mother Nature is going to give. And there's extreme variability. So there's a bit of resiliency there but there's also this fragility that’s been talked about, and that's something that we should all be worried about, right, because Aspen, Colorado River Watershed is sort of a significant watershed for California and a few other states in between. So it's incredibly critical. It's what we need to keep focusing on.

Greg Dalton: Jerry Blann, I've actually ridden my mountain bike on your resort, huffing and puffing during the summer time. It's fabulous but there were not many people doing it. And imagine, you don’t make as much money on mountain bikers as you do with skiers. So there must be limits to summer as an adaptation strategy, as a business diversification strategy.

Jerry Blann: Well, there certainly is. And summer in Jackson Hole with the gateway to national parks, we actually have a step up on a lot of resorts. Three million people would actually come through Jackson because the bed base in Teton Village are able to come and reside there and allow us to take care of them for a day while they might be venturing the rest of the week out in the Grand Teton and Yellow Stone National Parks.

And you're right. A small component of that is the mountain bike trails or riding the tram to the top to see the Grand Teton and those kinds of things but there's no question that we are all somewhat limited in summer. And so it's a different experience. But I would tell you that the opportunity provide a more diverse kind of experience for family in Teton Village. In our case, it's a great responsibility and an opportunity. I would tell you also, as Mike started to point out and did point out on the education piece, it's just another opportunity to educate our guests in the off season, if you will, about the energy issues and the environmental programs that are out there.

Greg Dalton: Dave Brownlie, it sounds like that some of the players who have some deep pockets would be able to weather this and diversify and invest, but it's really the smaller resorts who might be at risk. The little guys lose once again. Is that possible?

Dave Brownlie: Well, unfortunately I think that — if you look at the trends in the ski business, that what we've seen, actually, over the last 20 years where the smaller resorts aren’t able to adapt from a technology point of view, whether that's snowmaking, whether that's grooming equipment, whether that's a detachable lifts. And so that has been some of the history. As we go forward, winter still will continue to be very important to us. We, as an industry, have to do all the things that we can. I've been up in Whistler. One of our biggest successes was developing or run a river hydro project. And we developed — we put as much power back into the hydroelectric grid, BC Hydro, as we do take out on an annual basis. And those are the things that are not only great for us in terms of our quest to get a zero operating footprint.

Those are also great stories to tell to the public that come and visit us on an annual basis about the different things that we’re doing. Then there's a while adaptation part, continuing to invest in technology whether that's snowmaking, whether that's fuel reduction, whether that's energy reduction and then the diversification. In the summer time, we do over 500,000 visits. That's sightseeing, mountain biking, glacier skiing. And it's a very, very important part of our business. We probably invested over $100 million in that adaptation, diversification strategy over the last 10 years. So it is significant. It does take resources but we’re obviously committed to it both as a business and as a community. As a community, Whistler takes sustainability very, very seriously.

One of the things you talked earlier about what you do individually, what does your community do. We have a goal in our community that 75 percent of the people that work in our community live in our community. So we've got resident restricted housing. So those people can ride to work, can take transit or if they do drive, it's a very short use of their automobile. So all those things do add up and they all do tell a story. When people come to our resort from around the world, hopefully they can take some of those ideas, talk about them and take them back to where they're coming from.

Greg Dalton: Jerry Blann, how do you talk to people in Wyoming who might not accept that it's happening, climate change is happening? You sit at the bar in Jackson and someone said, “Ah, global warming,” what do you say?

Greg Dalton: Okay. Teton Pines golf course then.

Jerry Blann: It's a challenge, Greg. There's no question about it. However, I would tell you that the company in Teton County is a microcosm. It's a little bit different than the rest of the state.

Greg Dalton: We had the former governor of Wyoming here, Dave Freudenthal. He said, “Oh, Jackson is not Wyoming.” [Laughter]

Jerry Blann: And he made a point during his administration to note that [laughter].

Dave is a great governor. He really was. But honesty, the collaboration within our state is better than you'd expect. I belong to a group called Wyoming Business Alliance which, like I said, there's only 565,000 population in the entire state. And when the University of Wyoming plays football, it's the third largest city when that happens [laughter]. Like I said, the Wyoming Business Alliance is a collaboration of businesses throughout the state. And it is surprising. You come and you talk to that — largely, energy focused but ag and a whole series of the other industries within our state. And they get it. It's not that they're ignoring it. Some of the technology that's coming out at University of Wyoming and some of the other schools is terrific. Will it eliminate fossil fuels right away? No, but some of the sequestration that Anne mentioned earlier. Some of those opportunities, gasification, some of the liquefaction and some of those opportunities we think in terms of clean coal, there may be some opportunities there that present themselves.

Greg Dalton: Jerry Blann is President of the Jackson Hole Mountain Resort. We’re talking about skiing and snow at Climate One. Our other guests are

Mike Kaplan, President and CEO of Aspen Snowmass Resort, and Dave Brownlie, President and CEO of Whistler Blackcomb. I'm Greg Dalton.

Mike Kaplan, on that point about technology and making things cleaner, you have something — you get part of your energy from a closed down coal mine. Tell us about that.

Mike Kaplan: Yes. It's a really exciting project. So about an hour and a half from Aspen there's a little town called Summerset. And yes, it's got one of those bars that Jerry was referring to that you probably wouldn't want to stop at and hang out. It's just a little bend in the road. But interestingly, we've been on this quest to try and find clean fuel to add to our grid.

And after looking around, we were able to meet a group of really unlikely people and partners including the Owl Creek Mine, which is owned by Oxbow Mining. And we don’t necessarily agree on climate science.

Greg Dalton: Who owns Oxbow?

Mike Kaplan: Bill Koch. And so we don’t necessarily agree whether or not climate change is happening. Whether or not it's human caused but we’re able to engage in a very interesting discussion with them with the help of Vessels Coal Gas, an engineering company, our electricity provider, Holy Cross Electric Coop. And we all got together and said, “Okay. Let's not talk about what we don’t agree about. Let's talk about something we can agree on.” And like all coalmines, this Owl Creek Mine emits methane. And they've been working hard to make it a safe mine over the years. And it's a very gassy mine. So they've got a very sophisticated methane venting system that ends as — you get out of the mine in a pipe and the methane was going up into the air. As most people probably know, methane is an extremely potent greenhouse gas, 23 times more potent than carbon dioxide. So we’re able to sit down with that crew.

And the Owl Creek Miners, they were really frustrated because they work hard to make the mine safe and then this resource is just being wasted. They recognize it as a gas. And so we got together with his group and we said, “Well, let's capture it. Let's pump it through some generators and convert it to electricity.” And so as of today, we've got three 1 megawatt generators capturing this methane, converting it to electricity producing 24 million kilowatt hours of energy per year. That equals our total usage to hotels, four mountains, 15 restaurants and ski shops and all that stuff, our annual use of electricity in one year. But even more interesting, when you look at that conversion of taking this very potent greenhouse gas and converting it into electricity, it creates a — it triples our total carbon output, our total greenhouse gas emission. So it's pretty phenomenal, the leverage we’re able to get with a group of people who don’t agree with this on what's going on in terms of climate.

Greg Dalton: But they took something that was just evaporating into the air and made money of it. So they're pretty happy about that. Okay. Let's talk briefly about your own personal carbon footprints and then we’ll get the audience in here for the second segment talking about skiing and snow at Climate One.

Mike Kaplan, what do you do to manage your own personal carbon footprint?

Mike Kaplan: I do a lot in terms of changing the light bulbs and I have a solar panel at my house. But honestly, the most important thing that I try to do is be vocal, be vocal with elected officials both locally in the state and with Washington. And again, try to get them thinking about “Huh, this is a problem that this generation has to solve for the next generation. And we need to do something and enact some climate legislation at all levels, locally and nationally.”

Greg Dalton: Does Aspen have private jets?

Greg Dalton: Okay. Dave Brownlie.

Dave Brownlie: No private jets [laughter]. Fortunately we live in a pretty tight community with excellent valley trail system for running, walking, biking, and we utilize those trails. Again, we have a very supportive infrastructure in terms of recycling, everything from tin to cardboard to glass, all those things. And yes, a number of years ago we started the whole composting process within our house, which is great. And we've got three kids. And it's something that we talk about and it's something that is important from an education point of view. So it's important to us.

Greg Dalton: Jerry Blann, how do you manage your carbon footprint?

Jerry Blann: I like to walk. I just had a back injury awhile back. So that's my mode of transportation as much as I can personally. As both of these gentlemen have outlined, I think it's important that everybody here understand that we’re talking about scalability here a little bit. I'm the little guy with 500,000 skiers. These guys are 34x of what Jackson Hole is. Our community, however, has really stepped up in the play. There's a number of different — whether it's recycling opportunities and sewer opportunities and programs that we’re just initiating. So I think we’re right on the verge of moving ahead, not only as a community, but individually.

Greg Dalton: Let's include our audience questions. Welcome. Hi there.

Participant 7: In addition to the climate declaration, can you also talk about some other mitigation efforts in the ski industry? For example, is there any movement towards a collaborative effort to set industry standards for sustainability or to share your best practices?

Greg Dalton: Mike Kaplan, Aspen has been a leader in this area. Can you tackle that one first?

Mike Kaplan: Yes. There are efforts. Actually the environmental committee is chaired by

Jerry Blann for a number of years. There's a group called National Ski Areas Association, and there's over 300 members. And the National Ski Areas Association, probably 10 years ago created something called Sustainable Slopes to try and gather the industry hired actually — work in conjunction with NRDC, Natural Resources Defense Council, and the Brendle Group consulting on, okay, how do you measure carbon, how do you encourage and engage this National Ski Areas Association and its members to be focused on carbon and address it in a meaningful way. So yes, a lot of activities there. And it then creates successes thanks to — this industry gets it.

Greg Dalton: Jerry Blann, would you like to add to that from your time chairing the committee?

Jerry Blann: I was in the formative early years when we formed the environmental committee. And I took the opportunity to educate one. Trade organizations are difficult particularly ones that are primarily focused on making payroll when you look at the largest number of our resorts. And there are 300 and some odd in the National Ski Areas Association. As a priority, it's hard to elevate environmental efforts but I would tell you, as Mike indicated, through Sustainable Slopes, through setting standards, through a national annual report that the ski areas put out. We've started to refocus and educate, and I think started to bring people on in a significant way.

Greg Dalton: We’re talking about skiing and snow and climate change. Let's have our next audience question. Welcome.

Participant 8: Hi. I'm curious if this either happened or you first see it happening in terms of obtaining financing for new projects, new capital expenditures at your resorts. Does that ever come up in questions about the longevity of the industry or climate change affecting, payback of winning?

Greg Dalton: Dave Brownlie.

Dave Brownlie: Interesting. Maybe I'll answer that question just because I don’t know if you're aware but Whistler Blackcomb was monetized by Intrawest three years ago into an IPO. So we went out and became a public company three years ago. And out on the road, we actually did get asked that question a fair number of times. It is interesting. When you look at the history of whether — in Whistler Blackcomb what's happened is that we actually have a slightly growing snowpack over the last 30 years, and again, just because of the nature of where we are, et cetera, but we also a couple of glaciers and one that we ski on in the summer. And certainly in my time there in 25 years, I have seen that glacier deteriorate, and it's not from the winter snowpack. It's actually from the warmer summers. And as the ice melts and more rocks are exposed, it hits up, and that glacier melts faster. But when we talked to the investment industry, we say, “You know what? We’re a committed industry. We’re investing into new technology.” In our case, we've got a resort that has over a mile vertical. And we've invested in the higher alpine of the mountain, new lifts to peek which joins the two alpine lifts. And we've also got a very vibrant summer business that we plan to grow. So we certainly had a big story around that. And I think as we talk about today, certainly in my lifetime we will see change but I believe that our business will continue to be robust. But certainly, the long term future of skiing, in particular, as you start to eliminate some of the smaller resorts, call them the feeder breeders, it's probably where we, as an industry, will be challenged. But again, from an IPO perspective, those guys, once you got pass 10 years, they were okay.

Greg Dalton: Let's have our next question at Climate One.

Participant 9: Thank you. In just bridging the two programs — skiing has become more and more of an elitist sport with prices being in my lifetime having gone incredibly high. So it's a very tough sport for the average person to relate to while the climate change issue is something that affects everyone. So when I hear the two programs and look at sort of this group as an advocacy group for climate change — so I guess the question is why has the industry become even more elitist than it used to be? It's very tough for a family to afford to be able to be a skiing family now because of the lift prices. And at the same, how do you then reconcile that with an advocacy effort around climate change because I think there's a disconnect that is tough to bridge?

Greg Dalton: Disconnect or perhaps an opportunity.

Mike Kaplan. Who would like to tackle that? Jerry.

Mike Kaplan: Well, what you should do is buy a Mountain Collective Pass because it's a great deal [laughter]. It's only $3.79, on sale now at themountaincollective.com [laughter]. And not only you're getting a great value, but you're getting these resorts that are doing everything possible to try and increase public awareness of the issues of climate change and what they can do about it.

Jerry Blann: One addition to that is we all, as ski resorts, are represented by — our direct costs are about 40 — well, I should say it's close to 60 percent direct labor cost. And we have a workforce, I think, throughout our industry who come to resorts and actually select our resorts because of their environmental ethic and ethos. And I think that is changing and I think that is how we’re actually broadening our base. You may say that there's a hierarchy there but at the same time, I really do believe that employees choose an Aspen, choose a Whistler or choose a Jackson Hole because of what they're doing corporately to make a difference.

Greg Dalton: Another piece of that question which basically said you serve the 1 percent. The opportunity you have because your clientele are influential people who have power and influence in this country. And are you doing everything you can to reach them to say, “Wake up. You love skiing. Do more”?

Mike Kaplan: I think that's our duty as ski area operators that have that influential clientele that have such a high percentage of Fortune 500 CEOs coming to ski in our areas and recreate and have that time where they're not hammered by all the day to day responsibilities in their email, where they can actually think and they might be more open to being influenced by an ad that we have on sponsorship message that says, “Hey, do you want to ski with your kids in the future? If you do, get active and join POW. Do something about it.”

But then finally, I would say the industry actually — obviously, Aspen Snowmass and many of us here sort of our true destination resorts where we have extremely high cost of doing business. Trust me. We’re not gouging anyone. It's incredible expensive to operate a resort on a seasonal basis in such a remote location. But the industry as a whole has done a tone, especially over the last 10 years as Dave Brownlie was referring to, to really reach out and attract more people and make it more accessible for people to ski especially those that are located really close to metropolitan areas.

Greg Dalton: We've got time for one last question. Let's get this question in for Climate One. Welcome.

Participant 10: Hey, guys. Thanks. There's been a lot of talk about Mom & Pop's and the small to medium size ski areas or the feeder breeders. I like that, it's pretty cool. Can you guys speak from your perspective as kind of the leaders of three of the Mountain Collective, which are the biggest, and the best of North America? What's the value for the Mom & Pop's to you guys, to the entire industry, just in generally?

Dave Brownlie: Well, I certainly speak from my perspective. As you know, Whistler Blackcomb is on the west coast, just north of Vancouver, just in Vancouver, just right within the city limits. We've actually got three areas, Seymour, Cypress and Grouse Mountain. And they are the areas that get people into the sport. It's easy to get to. It's less expensive. It's less of a commitment. So they get people into the sports and they get people loving it. And then ultimately, they will come out to enjoy Whistler or many of the other great resorts in British Columbia. So they are very, very important to us. It's something that we talk about. We participate. For us, it's not NSA but it's Canada West Ski Areas Association.

And it's a very important discussion. And we’re proactive. We do what we can to help them out, all ski areas, quite frankly, in British Columbia because that is just going to get more and more people into a healthy environment and hopefully continue to ski and snowboard going forward. We have things, and I'm sure NSA, does where we provide opportunities for those folks in smaller areas to come to our conferences or if we have old equipment or old uniforms, pass them along, all those things that can make a difference because they are often just scratching to make payroll.

Greg Dalton: Rather than just making payroll, let's end on an upbeat note here. Who has a positive note to end us on?

Jerry Blann: NOAA says it's going to be an average winter. [Laughter]

Greg Dalton: So it's come to that. Average room is cause for cheering. Okay. We have to end it there. Our thanks to Dave Brownlie, President and CEO of Whistler Blackcomb,

Mike Kaplan, President and CEO of Aspen Snowmass, and

Jerry Blann, President of Jackson Hole Mountain Resort. I'm Greg Dalton. Thanks for coming to Climate One and thanks for cheering average. Thanks everyone.

[Applause]

[END]