What the Infrastructure Deal Means for Climate

Guests

Carla Frisch

Sasha Mackler

Beth Osborne

Michael Grunwald

Summary

After months of negotiations, Congress finally passed President Biden’s infrastructure act and he signed it into law. Though cut back from the original proposal, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act will pour billions of dollars into highways, roads and bridges, public transit, rail and EV infrastructure, as well as water supplies and broadband internet. It’s a massive piece of legislation and makes big investments toward climate priorities.

“It makes the largest federal investment in public transit in history and the largest federal investment in passenger rail since the creation of Amtrak. And really significant investments in EV: both the charging and the supply chain for electric vehicles,” says Carla Frisch, principal deputy director of the Office of Policy at the U.S. Department of Energy.

Early on, President Biden put climate justice at the center of his administration. Frisch says the infrastructure act will address some long standing inequities, including investing $15 billion in replacing lead drinking water pipes, delivering thousands of electric school buses and addressing brownfields and Superfund sites.

“Twenty-six percent of Black Americans and 29% of Hispanic Americans live within three miles of a Superfund site. And that can increase lead exposure in children. So, the bipartisan infrastructure law invests $5 billion in addressing legacy pollution at those sites and working to create good paying union jobs and healthier communities,” Frisch says.

But while the law makes a historic investment in public transit, cars and highways still get the biggest share of the pie.

“The climate gods will not care that this was a historic amount of transit funding if the historic amount of highway funding results in greater emissions,” says Beth Osborne, director of Transportation for America. She says the transportation aspects of the law are outdated, based on the longstanding priority of moving cars quickly.

“Nothing about this legislation changes that,” Osborne says. “It has taken a decades-old transportation program that's produced very poor results in both equity and climate, but also in safety in terms of building local economies in terms of dividing, usually black and brown communities, in terms of giving people equitable access to jobs and services in terms of costing people a lot of money. It's performed very poorly in all of those areas, and we're hoping for a different result from basically the same programs.”

Osborne says the overall impact of the money will depend in part on how much the U.S. Department of Transportation uses its administrative capacity and authority to encourage states to align projects with the administration’s overall goals.

Since the infrastructure deal is bipartisan, does that mean more federal investment in climate action will follow?

“Climate is becoming more mainstream and more politically acceptable as a policy matter at the federal government,” says Sasha Mackler, executive director of The Energy Project at the Bipartisan Policy Center.

“This bill really does create kind of a step change for the American energy innovation system in particular. Some of the most important challenges we face as a country as we look towards remaining competitive economically in the 21st century, which will be defined by how quickly nations can decarbonize and export those technologies to other parts of the world,” he says. “The Department of Energy is really going to be shepherding and catalyzing a lot of these things going forward. And the implementation of these dollars over the next five to 10 years will be the next important step in delivering these technologies for industrial scale decarbonization.”

Related Links:

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. Congress recently passed the biggest piece of climate legislation ever - the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

Carla Frisch: It makes the largest federal investment in public transit in history and the largest federal investment in passenger rail since the creation of Amtrak. And really significant investments in EV.

Greg Dalton: But while the numbers may be big, cars and highways still get the biggest share of the pie.

Beth Osborne: The climate gods will not care that this was a historic amount of transit funding if the historic amount of highway funding results in greater emissions.

Greg Dalton: Since the infrastructure deal is bipartisan, does that mean more federal investment in climate action will follow?

Sasha Mackler: Climate is becoming more mainstream and more politically acceptable as a policy matter at the federal government.

Greg Dalton: What the Infrastructure Deal Means for Climate, up next on Climate One.

Greg Dalton: How significant will the new infrastructure law be for addressing climate? I’m Greg Dalton. After months of negotiations, Congress finally passed President Biden’s infrastructure act and he signed it into law. Though cut back from the original proposal, the law will pour billions of dollars into highways, roads and bridges, public transit, rail and EV infrastructure, as well as water supplies and broadband internet. It’s a massive piece of legislation and makes big investments toward climate priorities. I invited three guests to dig into the law’s strengths and flaws. Carla Frisch is Principal Deputy Director of the Office of Policy at the US Department of Energy. Beth Osborne is Director of Transportation for America. Up first, Sasha Mackler, Executive Director of the Energy Project at the Bipartisan Policy Center.

Sasha Mackler: This is a really big deal not only for energy and climate, but for the infrastructure system and for the larger, more for the economy generally here in the US. We've been waiting for I would say more than 20 years for an infrastructure bill seems like every week is been infrastructure week for a very long time. And we finally got this bill across the finish line, and it really does represent a step change in our public commitments to many parts of the economy, but especially for climate change.

Greg Dalton: Carla Frisch, this is obviously a big win for the Biden administration and we’ll drill into the details on the show. But how will this package cut climate eating emissions?

Carla Frisch: This bipartisan infrastructure law is a very significant investment in cutting emissions. And at DOE we like to call ourselves the solutions agency and that we work on a lot of the technologies and systems that will do just that.

Greg Dalton: Beth Osborne, you issued a statement after passage of the infrastructure act saying “It will fail to produce meaningful shifts on climate and equity.” Why do you say that?

Beth Osborne: Well, the change in the bill on the vehicle side is wonderful and exciting, but it's very status quo on the transportation program. It has taken a decades-old transportation program that's produced very poor results in both equity and climate, but also in safety in terms of building local economies in terms of dividing, usually black and brown communities in terms of giving people equitable access to jobs and services in terms of costing people a lot of money. It's performed very poorly in all of those areas, and we're hoping for a different result from basically the same programs. Now, that's gonna depend on exactly how aggressive US DOT is in using their administrative capacity and authority. And it’s also gonna depend on how much each of the 50 states wishes to change their behavior and investment.

Greg Dalton: Okay. So, yeah, states got a lot to say on this. So, Carla I recognize you are with the Department of Energy, not the Department of Transportation, but can you respond to what Beth says there.

Carla Frisch: One thing Beth is pointing out is this is one step of investment. So, we got the bipartisan infrastructure law, which has passed and been signed by the president and we are very excited about. And then the second piece is the Build Back Better Act, which just passed out of the House and that includes additional investments. But today I think we’re talking about the bipartisan infrastructure law and I will point out it makes the largest federal investment in public transit in history and the largest federal investment in passenger rail since the creation of Amtrak. And really significant investments in EV both the charging and also at DOE on the supply chain for electric vehicles.

Greg Dalton: Sasha Mackler, these are big numbers and yet there's 110 billion for new spending on highways, roads and bridges while there’s 39 billion for public transit. 86% of the population in the US lives in urban areas where good public transit can play a big role in getting people out of cars and cutting climate eating pollution, improving public health. So, is it a good thing we’re still spending three times more on car infrastructure rather than public transit, acknowledging that the numbers are big but the proportions are still car centric.

Sasha Mackler: Well it's true that the proportions are car centric. But I think what we really need to do is look at the trajectory here. The investments are really stepping up across the board in infrastructure for transit and that’s gonna make a big difference. It will help to modernize transit which should make it more appealing to use. I think that's really kind of the key insight and the core priority here. As we look ahead to how this country will grow over time and will reduce emissions, we need to find ways to get the emissions out of the vehicle fleet, and this bill will do just that.

Greg Dalton: Beth Osborne, your organization says that states often choose to spend federal dollars on expansion over highway repairs. It’s more appealing for a politician to cut a ribbon or point to a new highway than it is to a repaired bridge or perhaps a scheduling system for a transit agency. Is this time any different? Is there gonna be a bias toward expansion over repair?

Beth Osborne: I certainly think we can all hope that everybody woke up the morning of the signing of the bill and was transformed by the hope for the future. But in my experience, they need a little bit of a push in that direction and this bill offers none. In fact, this effort rejected an effort on the House side to say that before a state could build new capacity, they had to demonstrate they had a plan for maintaining it along with the rest of their system. We require that on the transit side. On the highway side we have and we continue to allow a state to say we have no idea how we'll maintain it and we're going to give up on other pieces of infrastructure and that has been maintained. The fact of the matter is that this end approach to transportation will invest a historic amount of money in transit and a historic amount in highways in the 1950s approach has never produced the results that we are hoping for. We really need to invest according to a goal or an outcome not just according to pouring amounts of money in individual pots. That's not how people travel and the climate gods will not care that this was a historic amount of transit funding if the historic amount of highway funding results in greater emissions.

Greg Dalton: Right. You talk about induced demand, the idea that expanding roads encourages people to drive. This comes at a time when driving is quite painful. Rising gas prices are causing worries about inflation, angering drivers and making politicians nervous, even though the price of gas is tied to global oil prices set largely by OPEC not determined by the US President has very little influence on the price of gasoline. Here's Trevor Noah's take on all this.

[Start Playback]

Trevor Noah: What’s tough for Biden is that it doesn’t matter what else he does. If the price of gas stays high, that's that. He could sign all the infrastructure bills he wants he could get everyone to agree on abortion, but all people care about is how much is the black goo from the ground. Higher than before then get the -- out of here. So, it’s not exaggerating to say that his whole presidency, his entire presidency could depend on will the gas prices stay up or go down.

[End Playback]

Greg Dalton: Sasha Mackler, US presidents have very little influence on the price of gas and yet their fate is often tied to it. And this is true of many US presidents going back decades. That was Trevor Noah's take, what's yours?

Sasha Mackler: Yeah, well I think Trevor makes a really good point, which is that you know the price that people experience at the gas pump really does make a difference in how they feel about the economy and how they feel about the performance of the administration or any you know the government writ large. And so, when we think about energy and climate and associated policies, we really need to take the view that there are a number of factors that need to get managed simultaneously. And that's really what we mean by the energy transition. We need to manage the near-term as we drive towards the long term. And managing energy prices, managing reliability and affordability of energy as we transition towards a net zero economy is a very complicated task. And when we talk about this infrastructure bill and as we think about this infrastructure bill it’s not the case that this is the climate bill for the US but it is a climate bill. It definitely is a piece of the larger puzzle but it’s not the only thing we need to do, we need to be thinking about other mechanisms other programs. Carla mentioned the Build Back Better Act that has a number of provisions in there that are geared towards lowering the price of clean energy technologies. There are things we need to do beyond that to recalibrate markets, put regulations in place that will provide a long-term goal on emissions and clean energy. But this infrastructure bill does do a lot and we should think about it in the way you know that when we think about home buying, this is like a down payment. It's a major investment in the sorts of technologies, innovations, and the systems that we will ultimately need to bring forward and have be commercially available if we’re gonna hit our net zero targets. And that down payment which is historically significant here in clean energy will help to reduce the costs and bring forward in time the technologies that we’ll need to hit our goals. And it’s an important piece of the puzzle.

Greg Dalton: Right. And we should recognize that this was what was possible getting through Congress -- even Democrats -- there are still fossil fuel states that have a lot of influence over what came out of. Carla Frisch, some look for the president to sell the strategic petroleum reserve. In fact, the infrastructure act includes selling $6 billion from that reserve to pay for these new investments we’re talking about. How is the administration navigating public concern over gas prices while implementing this bill and should some of that strategic petroleum reserve be sold, you know, should we sell more of that?

Carla Frisch: We've heard from the president directly that he believes that Americans should have access to affordable energy at the pump and at home. And when you look at current high energy prices from fossil fuels that really reinforces the need to diversify our energy sources in the US and adopt sustainable energy sources. So, we’re not overly reliant on any one source of energy for our economy for our communities. So the infrastructure law and the Build Back Better Act help do just that. One thing that was just passed in the bipartisan infrastructure law is an increase of $3.5 billion on DOE's weatherization assistance program. And that makes investments to help with low income residents help weatherize their homes, increase energy efficiency, increase the health and safety and reduce costs for those low-income households, really by hundreds of dollars every year. So, that type of investment paired with the other investments in the bipartisan infrastructure law are helping us get to a longer-term sustainable set of prices in the US.

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation about the climate impacts of the new bipartisan infrastructure law. Our podcasts typically contain extra content beyond what’s heard on the radio. If you missed a previous episode, or want to hear more of Climate One’s empowering conversations, subscribe to our podcast wherever you get your pods. Coming up, Beth Osborne with Transportation for America says for decades, the top priority for transportation funding has been to move cars quickly.

Beth Osborne: And nothing about this legislation changes that. And when you prioritize that you de-prioritize local businesses where it turns out people driving past your storefront at 45 mph aren't the greatest window shoppers.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. We’ll continue my discussion with our panel later in the show. To get another view of the scale and impact of the Infrastructure Law, we invited journalist Michael Grunwald to weigh in. He’s worked for Politico, the Washington Post and is author of The New New Deal, focused on President Obama’s 2009 stimulus package. He spoke with Climate One’s Ariana Brocious.

Ariana Brocious: In a 2012 article for Grist featuring your last book, the new new deal, David Roberts wrote very few people understand the scope or impact of the Stimulus Bill during the Obama administration. Can you give us the short-hand version of what we should understand about that bill?

Michael Grunwald: Well, as the title of my book suggested it was a really, really big deal, it was $800 billion, and the main point of it was to prevent a second Great Depression, and it was very successful that way, it saved and created millions of jobs. the recession was over within four months of it passing, so it was incredibly successful as just an economic measure, but it also had some longer term effects, it included 90 billion for clean energy at a time when we were only spending a couple billion dollars a year, so it really sort of jump-started some of the advances that we've seen in solar electric vehicles, wind, LED lighting, it had tremendous long-term investments in transportation and broadband, and some of the infrastructure stuff that you're seeing in the Biden bill of 2021. Really, it was essentially the Obama agenda passing a month after he took office, so it was really pretty audacious from The Audacity of Hope guy.

Ariana Brocious: Well, you just touched on a few of the specifics relating to climate and clean energy, and I wanted to go a little further into that, so I think the general public may not, well, understand how much of that money went toward these industries like clean energy, and that had some really lasting impacts, and I was hoping you could give us a couple examples, one that comes to mind is Tesla, right? That got a big loan, and at the time was a pretty small company, and now, of course, is a gigantic company helping reshape the auto industry. Could you give us a couple of other examples like that?

Michael Grunwald: Sure. The basic idea was... And it's hard to imagine now and now that we really have a clean energy industry, but there wasn't one in 2009, and in fact, the only industry that had sort of gotten going a little bit, which was wind, there were turbines literally rusting in the fields because of the financial crisis. So what the Obama stimulus did was throw a ton of money into clean energy, but the idea was not to pick winners and losers, but to pick the game, it was... Everybody was gonna get something, there was money for biofuels, there was money for carbon capture, there was money for solar and wind, and within those categories, there were manufacturers and consumers and just every imaginable way you could think of going green. And the idea was, Well, we'll see what works. And so solar was a huge, huge victory for the Obama stimulus, and today we've surpassed some of the 2050 goals for solar that were set back in 2009, solar wind LED lighting, electric vehicles. You mentioned Tesla, it was on the brink of bankruptcy. When the stimulus was announced, they got a loan, they were able to pay back six years early, and today they're the most valuable car company in the world, Alot of these bio-energy plants failed, a lot of the Carbon Capture investments failed, Solyndra obviously failed, some of the battery industry, battery investments failed, but the idea was that some of them would succeed and they would help launch a transition away from fossil fuels. And to that extent, the Obama stimulus was really successful.

Ariana Brocious: So compared to the Obama stimulus act, how big of a deal is the new bipartisan infrastructure act?

Michael Grunwald: The Obama stimulus was 800 billion, mostly over two years. The infrastructure bill is, it's really maybe 600 billion in new money over five years, so it's not as big. Biden's real big one is the Build Back Better bill, which has not yet passed, and they're still trying to negotiate in the Senate, but it's still a very large investment. The Obama infrastructure investment was touted as the largest since Eisenhower started building the interstate highway system, and this is certainly the largest since then, and remember, Donald Trump spent four years talking about how he was going to be a builder and he was gonna do infrastructure and infrastructure week became a big joke, and now Biden is actually getting it done in a bipartisan way. It's not as ginormous as he might have hoped, but it's a very significant step that's going to definitely have some big changes, particularly in the world of clean water infrastructure and broadband because we already spend a lot of money on transportation, it's still... It's a lot of money and it's a big deal.

Ariana Brocious: So how is the Biden administration handling the narrative and communication with the public around these two big bills, both infrastructure and build back better, what lessons might have been learned from the communication… the successes or failures of the Obama stimulus package here?

Michael Grunwald: Well, certainly... One theme of my book was that the Obama stimulus was, in many ways, wildly successful and yet wildly unpopular, which... Believe me, Ron Klain and Joe Biden were deeply involved in the Obama stimulus, and they noticed. So certainly they are trying to do what they consider better messaging now in terms of trying to highlight the successes more, in terms of trying to let people know what they're getting for their money. But I do think it's arguable that one lesson from the Obama stimulus is that it's just really hard to get credit for doing stuff. The Republican did an excellent job of finding a couple of studies where they were studying the influence of cocaine on monkeys or some tunnel that was supposed to help turtles avoid getting hit by cars, and they made the entire 800 billion sound like it was all about cocaine monkeys and turtle tunnels, in ways that was really made it sound like just a big government, big spending, big mess. And I do think one lesson of the Obama stimulus is that messaging this stuff is hard, people don't pay very close attention to what's happening in Washington. So one glass half empty way of looking that is that no matter how you message things, you might be screwed no matter what... And no good deed goes unpunished. But the flip side is that, hey, people are gonna react how they react. You might as well use your government job to do government stuff, and I do think that is one of the lessons that the Biden people have learned. They're really gonna focus on the policy and they'll try to sell it as well as they can, but I think the policy is the most important thing.

Ariana Brocious: As you've said, Biden’s Build Back Better Act really is where most of the climate money is between these two bills. If Congress manages to pass that bill too, what do you think will be the combined climate impact of these two bills?

Michael Grunwald: The Build Back Better Act would really build on the start in the infrastructure bill. For electric vehicles, there would be just a ton of money, not so much for the infrastructure, but to make it more attractive for consumers by giving them money and rebates for buying them, the same goes for when... For solar, for energy, electricity storage, for geothermal, there are gonna be really big tax credits and other incentives that are... We're talking about hundreds of billions of dollars to really get this stuff going, to deploy at a much faster rate. And that's how you move the needle in a big way. I mean, Joe Biden’s goal is essentially to phase out coal by 2030, and you can't do that without something to replace that, and so I think if the Obama stimulus jumpstarted wind and solar and LED lighting and electric vehicles, the idea of build back better is to really bring it into the mainstream, because think there's a feeling that it's gonna be very hard to convince 350 million Americans to go green because the polar bears are in trouble, but it's not as hard to convince them to do something that's gonna save them a lot of money. Solar and wind power in many ways already there, electric vehicles are ready pretty much a good deal over the life of the vehicle, but this is a way to really try to say like, Hey, it's becoming a no-brainer, just do it, and when you start to get tens of millions of people rather than thousands of people making these changes, that's when the emissions needle really starts to move.

Ariana Brocious: Michael Grunwald is a journalist, formerly with Politico, the Washington Post and The Boston Globe, and author of The New New Deal. Michael, thanks for joining us on Climate One.

Michael Grunwald: Thanks for having me.

Greg Dalton: Today we’re talking about the climate implications of the new bipartisan infrastructure act. My guests are Carla Frisch, Principal Deputy Director of the Office of Policy at the US Department of Energy. Sasha Mackler, Executive Director of the Energy Project at the Bipartisan Policy Center. And Beth Osborne, Director of Transportation for America. A hundred years ago streets were the domain of people, horses, and a few automobiles. Then cars took over in part because of a dominant car-centric culture that automakers manufactured and helped promote. The COVID-19 pandemic helped reclaim some public space for people with slow streets and street closures, but it’s too early to say how long that may last. I asked Beth Osborne if the Infrastructure Act includes spending on what’s known as “complete streets” that work for everyone.

Beth Osborne: There’s a very small amount of money available for that. I should be clear it’s an incredibly flexible program. All of the money could be spent on complete streets. They never have before; they're unlikely to suddenly do so now. The general approach to addressing a problem in transportation is to say we should create a program to fix identified problem. For example, climate emissions, so we’ll create a $6 billion climate emissions reduction program and then we’ll spend $50 billion a year on the traditional thing that drives up emissions. And we do the same with complete streets. Here’s two and a half billion dollars a year for safety and here is $50 billion a year for not safety. And so, I think it’s gonna take more than money. Money has never solved this in the past, but we tried it over and over we get the same promises. It really requires policy and that's gonna rely on the administration to lay down the law in the way they implement these programs and there’s a lot of things they can do. There's a bunch of cities that have experimented during COVID and had some really good experience, but their state runs this program again by the way it was designed by Congress. And states often stomp on the city's desires to create that kind of environment and it will be up to US DOT to tilt the scales a little bit more in favor of those local governments.

Greg Dalton: Sasha Mackler, is there danger on being so flexible I mean this is the way American democracy works, right. Federal government gives some guidelines and money to states and states are the laboratories where they get to implement these things. Is there danger in the flexibility as well as perhaps opportunity?

Sasha Mackler: Well, I think what really can transpire here is that the states then if they take the responsibility seriously and if they work in collaboration with the federal government. They can really, really design programs that are fit for purpose for what's happening on the ground in those locations, but this really does require federal leadership. And one of the things that I think is really notable about this infrastructure bill and about the general political environment in Washington right now is that this infrastructure bill as we talked about you know as we’ve been discussing here is a profound step forward. It really puts out enormous resources that are geared explicitly towards climate and it’s a bipartisan bill. And I think we have to pause and think about that for a minute. Climate is becoming more mainstream and more politically acceptable as a policy matter at the federal government. We had the Energy Act of 2020, which was a bipartisan bill unlocking major new programs geared towards climate and technology. We have the infrastructure bill again a bipartisan program unlocking spending and new programs out towards energy and climate. This is important and I think it portends more to come.

Greg Dalton: Carla Frisch, let's talk about the states, you know, the states may not be so bipartisan. There are a lot of states, there’s red states and blue states some purple states but your take there on how this is implemented in the states and the flexibility they have in those political contexts.

Carla Frisch: Well, the states have an important role here and as Sasha was pointing out, we have seen climate action from all parts and levels of society in the US. So, we’ve seen state governments, local governments, private sector actors regardless of party affiliation really stepping up to the plate and taking action on climate because they know that will deliver for them and their community sustainable prices more job opportunities and better health outcomes. Now the design of this bipartisan infrastructure law does provide significant opportunities at the state level. So, some of the dollars move through formula to states. Some dollars will be delivered competitively to states to city and local governments to tribal governments and to their partners. And some of that will go out immediately. Some of it requires new program design. So, it’ll take a little bit longer. But one of the unique aspects of this bipartisan infrastructure law compared to even 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act is about the time frame as most of the programs in this law are looking at 5 to 10-year timeframe. So, a sustained investment in competitiveness for the United States.

Greg Dalton: Right, right yeah. And so, one reason why it maybe won't have the huge hit on inflation that some people are worried about. So, for thousands of years humans, Carla, have burned stuff to cook and keep warm. Wood, then coal, then oil, you know, combustion is incredibly inefficient. According to energy guru Saul Griffith if we electrified everything, we would need half of the primary energy that we’re using now. This math still so boggles me. We can electrify everything and need less energy because combustion burning stuff is so inefficient. So, is the administration is this willing to move away from fossils and sunset fossil fuels faster because that seems to be a problem even for Democrats.

Carla Frisch: So, we are moving toward sustainable energy as quickly as possible. And some of the investments in the bipartisan infrastructure law that mirror the principle that you're saying include $27 billion investment in the electric grid and clean energy. So, the more and more we electrified transportation and our buildings and industry where it makes sense to do so the more we’re gonna be able to we need to make sure that we can move that electricity to where it’s needed So, the bipartisan infrastructure law includes investments to bring electrical grid into the 21st century to make sure that it's resilient against extreme weather and cyber. It also establishes a new transmission facilitation program for DOE to help make sure that we can get that transmission built across the country. In parallel to that there are significant investments through DOE in expanding access to energy efficiency and clean energy for families, for communities, for businesses through the low-income weatherization that I mentioned but also through investments in county and state level programs and particularly in schools to make sure that they can take advantage of that clean electric energy and use that in transportation or in their buildings.

Greg Dalton: Sasha Mackler how big a deal is this grid modernization we have a grid that is vulnerable to cyber-attack. We have a grid that is built not so much for renewables that come and go over different times of the day.

Sasha Mackler: Yeah, the grid does need to be built out, hardened and expanded. And that requires investments which the infrastructure law does have as a part of it that was just outlined by Carla. There are also some provisions in this law that center on the permitting side and the planning side of the grid. Because I think when you start to unpack this issue of how we electrify which I share the view that the more we electrify generally, the better it is for climate emissions and for energy efficiency and probably for cost as well. We need to have the tools to build the electricity grid more quickly than we can today because if you're involved in the energy sector you know that it is extremely difficult, time-consuming and more expensive than it needs to be to try to site and build and finance long-distance high-capacity power lines. And so, improving the permitting process is really one of the core things that we can do to help with the energy transition it’s not very well appreciated and this bill does do some really important things it creates an office of transmission planning at the Department of Energy it has new financing authorities to help to get developers into the mix and take those risks in sort of trying to develop these projects. And it has some, you know, I think really significant bureaucratic changes around permitting and federal coordination of the permitting process so that these projects don't get hung up in red tape and can move through still with the right environmental safeguards but just move more quickly because we need to really race to get this infrastructure built out and the enabling pieces the infrastructure, the electric transmission is really key to all that.

Greg Dalton: Some environmentalists hearing that Sasha might think of you know the desert turtle the sage-grouse. There's been a lot of environmental anxiety, concern about big ugly transmission lines going through sensitive habitats. So, are you saying we need to loosen environmental protections, that might be necessary to get to the climate goals?

Sasha Mackler: This is I think really going to become one of the most important and complicated parts of the energy transition is how do we build this infrastructure quickly and I think justly, right. And there’s no easy answers. First of all, what I would say is we have a lot of existing right-of-way in this country and we could even look to the highway system as one example of a right-of-way that could be leveraged for other infrastructure like transmission. We need to do more thinking and planning there and unlock some of the barriers around how the state and federal governments can work together around leveraging existing rights-of-way because that will reduce the opportunities for conflict. The other thing that I would say is if climate and climate goals are our highest priority that you know one of our highest priorities as we look ahead to the economic and environmental and personal safety of Americans, then that by definition means that other priorities have to be subordinate to that.

Greg Dalton: Want to get back to transportation. Beth Osborne, you know, Transportation for America notes that our roads are deteriorating despite unprecedented levels of funding including windfall funding from the 2009 recovery action. And you said that we have a great track record in throwing more money at transportation in this country. What were the specific lessons of the 2009 Stimulus Act and have those lessons been applied this time around?

Beth Osborne: There are a whole bunch of things that we learned in that effort. One, is that when you get a windfall of funding you tend to go into your projects that may be didn't make it into your last round of funding. Those projects aren't always the most visionary they just may be the ones that are hanging on year after year, and for various reasons sometimes because there might be a little controversy over them just kind of hang around. They’re not always repair projects often they aren't often they are decades-old expansion projects that now just get funded. So, it would have been great to require kind of a reanalysis, maybe according to some of the priorities we’re discussing before money went out. We learned that shovel ready wasn't a good measure. This being a five-year bill moves very far away from that thank heavens that was just a mess of an approach. And it does have a longer-term approach even if it isn’t prioritizing anything new. The overwhelmingly most important priority in transportation and has been for the last 70 years is to move cars quickly. And nothing about this legislation changes that. And when you prioritize that you de-prioritize local businesses where it turns out people driving past your storefront at 45 mph aren't the greatest window shoppers; it creates high levels of damage in terms of crashes and life as you're driving faster the amount that you can view and take in shrinks. But the amount of time you have to react to spot and react to a potential conflict also shrinks and crashes are more likely to be deadly. So, that person trying to get to transit that we’re gonna invest a whole lot in when they have to cross a roadway built for a vehicle speed might find that they're taking their lives into their hands. And those fatalities fall much harder on black and brown people, particularly Black Americans and Native Americans. So, that's why I say one thing that I learned is that it's not enough to focus on competitive grants. When I was in the Obama administration we are very excited about our competitive grant program and we didn't spend enough time looking at the way the formula dollars went out. And that's still the bulk of spending and I hope this administration learned a lesson from my team and does better than we did. And that’s gonna require some aggressive administrative actions across the board.

Greg Dalton: You're listening to a conversation about the new infrastructure law. This is Climate One. Coming up, putting money into American energy innovation:

Sasha Mackler: What we’re seeing the beginnings of here, I would argue, is really a uniquely American approach to climate innovation. And the implementation of these dollars over the next 5 to 10 years will be now the next important step in delivering these technologies for industrial scale decarbonization.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. We’re talking about the new bipartisan infrastructure act with Carla Frisch, Principal Deputy Director of the Office of Policy at the US Department of Energy. Sasha Mackler, Executive Director of the Energy Project at the Bipartisan Policy Center. And Beth Osborne, Director of Transportation for America. Burning fossil fuels disproportionately affects communities of color because refineries, factories and highways have most often been thrust in those communities. Early on, President Biden put climate justice at the center of his administration. I asked Carla Frisch how the infrastructure act will address some of those inequities.

Carla Frisch: One that really sticks out to me is the significant investment $15 billion in replacing lead drinking water pipes. So, that's absolutely something we have to move away from for health of communities across the US. Similarly, there’s an investment in Brownfields and Superfund sites. So, 26% of Black Americans and 29% of Hispanic Americans live within 3 miles of a Superfund site. And that can increase lead exposure in children. So, the bipartisan infrastructure law invests 5 billion in addressing legacy pollution at those sites and working to create good paying union jobs and healthier communities. One more that really sticks out to me is the electric school buses. So, this is another place where we got more than 25 million children and thousands of bus drivers riding those yellow school buses and most of them are back at school now. And 95% of those buses run on diesel and that pollution from diesel is linked to asthma and that also particularly affects communities of color. So, in the bipartisan infrastructure law there's investment to deliver thousands of electric school buses nationwide, prioritizing rural and low-income communities and helping school districts make the investments to have clean, American-made, zero emission buses.

Greg Dalton: Sasha Mackler, Joe Biden's popularity is sinking. However, a recent Politico morning consult poll found that Americans overwhelmingly support the bipartisan infrastructure package that we’re talking about by a margin of 23%. We talked about gas prices and presidential popularity but what does this popularity of this particular bill mean for implementation?

Sasha Mackler: This bill really does create kind of a step change for the American energy innovation system in particular. Some of the most important challenges we face as a country as we look towards remaining competitive economically in the 21st century that will be defined by how quickly nations can decarbonize and export those technologies to other parts of the world. These investments really need to be designed their programs need to be designed well, the investments need to go into projects that deliver. And that implementation will be complicated, right. And so, the private sector needs work with the public sector here with the DOE arm in arm to get these programs and this project here I would argue is really a uniquely American approach to climate innovation. What we see in other parts of the world you know, for example, in Europe or in China a very top-down public-sector approach to dealing with climate change here in the US what we’re seeing is the private sector investment capital entrepreneurs at the center of what we will begin to witness as a you know rapidly I think innovating in decarbonizing energy system. And the Department of Energy is really going to be shepherding and catalyzing a lot of these things going forward. And the implementation of these dollars over the next 5 to 10 years will be now the next important step in delivering these technologies for industrial scale decarbonization.

Greg Dalton: Well, Carla Frisch, what are we talking about? Are we talking about battery cars that are not lithium-ion are we talking about biofuels that actually work? Are we talking about new forms of nuclear? Tell us a little about these innovations: where are the dollars being directed?

Carla Frisch: All of those and more so that’s a good starting list. So, one thing that the bipartisan infrastructure law does is invest in clean energy demonstrations through the Department of Energy. And demonstration is a really important step in the technology development process. So, you start with the research then you do the development and at the demonstrations stage you’re doing the first of a kind or a commercial scale project. It’s not quite ready for private sector investment. You got to test it out, you got to make sure it works before you get to the deployment phase where you are having private-sector investors ready to go all the way in. So, in that demonstration step the law invests 21+ billion dollars and that includes clean hydrogen demonstrations across the country. It includes carbon capture both direct air capture, pulling carbon out there and industrial emissions reductions. It includes advanced nuclear demos and it includes demonstration projects in rural areas, and a set aside for demonstration projects in economically hard-hit communities. And one of our principles at the Department of Energy is thinking about place-based investments. So, we’re thinking about how can we get the technology to the next level to where it needs to be but at the same time that we’re doing that how can we make sure that those demos are in communities across the country, in diverse communities across the country that have the particular characteristics and skills that can support that kind of technology. There's an opportunity here both on the technology front and on the community front.

Greg Dalton: And so, as I hear you say all these things I’m having a bit of a flashback to the last time we had a big infrastructure, energy investment on this, you know, it was much smaller than this, Carla, but it was 2009 and there were some investments that were made that were highly successful. So, Carla, what is the administration doing to sort of tell the story and learn from last time?

Carla Frisch: What we’re focused at Department of Energy is one, really significantly moving towards reducing our emissions consistent with the president's goals. Two, making sure we’re doing that alongside growing the opportunity for clean energy jobs with family sustaining wages in the US. Three, really looking at our domestic competitiveness of how can we onshore manufacturing and make sure that we’re creating the things here. And more and more, including, four, our energy justice communities. We’ve got the justice forty initiative across the administration which is focusing on making sure that a portion of the benefits of these federal investments are going to energy justice communities who in the past have suffered and not fully gotten the benefits of the transition to clean energy that we’re starting.

Greg Dalton: Beth Osborne, let’s get your view on lessons from last time the storytelling got away there were some success, but the story the narrative got away from the Obama administration. Do you see that changing this time what are the lessons?

Beth Osborne: Well, I hope that some of the lessons have been learned. I think some of the things Carla just said are so important. I mean how many car companies have gone out of business over the last hundred years. I mean, it's quite literally hundreds. Innovation involves failure. I hope that one of the things we've learned is that we should be much more upfront about the fact that we’re gonna try things and if it's innovative, it's not always gonna work. And so, I hope that we’re a little bolder about that and we just admit that up front because it's the only way we can be a part of anything close to innovation. Like I said before, I really do hope that we learned that it’s gonna require the administration steering the way the program is implemented and not just crossing its fingers and hoping that 50 states one by one, determine that they are going to match the president's priorities. I wanna point out that when it comes to transportation it is truly bipartisan and I mean that in all the best and worst ways possible. The status quo is fantastically bipartisan. That's what we saw with the Senate bill; that was a status quo transportation bill, very bipartisan. Innovation is also very bipartisan. It's just different Republicans and Democrats in those camps. And I'm hoping that maybe we can push a little bit more in the favor of the Democrats and Republicans that are doing things differently and push those that are stuck in a 1950 status quo towards those innovators. We didn’t try very hard in this negotiation. For example, we still allow states to set a target for more people to die on their roadways. And so, long as they don't beat their inflated number of more people dying on their roadways, they can flex their safety money away from safety. I hope that the administration decides to clamp down on that a little bit administratively going forward because the fact of the matter is safety particularly for those outside of an automobile is climate policy. And so, long as we make it a death match to walk people are going to choose with air quotes “not to walk” because we've made it terrifying.

Greg Dalton: Beth Osborne, you say rail was a big winner. There is another big piece of this we haven't talked about why is rail a big winner?

Beth Osborne: I mean it’s gotten not only a huge investment but over five years. This is a really bold level of investment. This is another opportunity to learn from the lessons of the Recovery Act. And what we learned is it’s not enough to put money into a wholly new mode. There has to be more that goes with it. We need a robust Federal Railroad Administration that was built around safety regulations not around capital expenditures. They’re gonna need to hire probably hundreds of people to implement this fast-new program and quickly. We also are going to require especially if we’re gonna invest in Amtrak it would help if the president would nominate some people to the Amtrak board. Right now, other than the CEO of Amtrak and the Secretary of US DOT there are no members who are serving under a current term; they're all expired. So, it’d be great to fill out that board. And also, it’s gonna take a very strong hand in dealing with the freight railroads that have been very successful throughout time, but definitely in the last 10 years or so in blocking the moving of passenger rail projects. So, again as it’s always the case money is not enough. It really takes leadership from the federal government and it's gonna take some policy. And the good news is the team at US DOT is outstanding and if they are empowered to take those steps we’ll be in great shape.

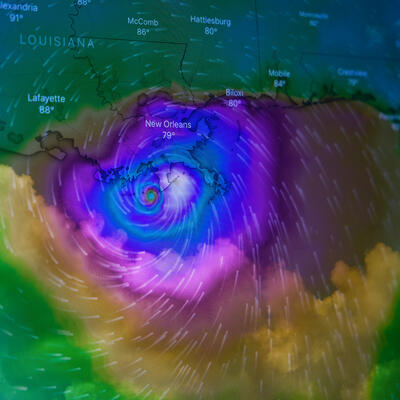

Greg Dalton: Sasha Mackler, we’re getting to the end, but I would be remiss if I didn't mention you have $47 billion for resilience to protect people from fires, floods, other extreme events amplified by burning fossil fuels. Where is that money going, what's that gonna mean for people we confront climate change it’s here today now.

Sasha Mackler: Yeah, so, resilience is such an important part of our climate strategy generally and of this bill as well. I mean the infrastructure that needs to be put in place to make cities, towns the nation in general, more sort of prepared for the climate change that we expect to see from greater storms from, you know, droughts these sorts of things, that's hard infrastructure that really needs to get invested in and built out as we look ahead. And those sorts of programs and investments are in this bill in addition to resilience of the grid. And this is really sort of a critical piece of our functioning economy and we are starting to see some vulnerabilities that are really taking a toll on communities and our economy just in the last year if you look at what happened in Texas. These sorts of things are very serious both for human health and for our economic well-being and the investments to harden our infrastructure against these expected changes really are part of this package.

Greg Dalton: As we wrap up I wanna look ahead and ask first starting with Beth. What was shifted to the Build Back Better legislation we know that there was a lot of climate things in this infrastructure bill they got shifted to the other bigger one. A lot of big climate in there, what are you looking at that was shifted out of this, and what are the prospects for that getting through because now it's been passed by the House it’s at the Senate.

Beth Osborne: There’s some additional money for electrification, something when gas prices are going up is incredibly important. I’d point out though that gas prices is a very small portion of the cost of owning cars so maybe we can also seek ways to reduce people's reliance on cars. And another part of the Build Back Better proposal is a provision to connect people in affordable housing with higher-quality transit. It's $10 billion. It is not only an important provision. It is a restoration of the bipartisan infrastructure agreement. They agreed to $49 billion and it was the only thing they abandoned in the bill of the bipartisan agreement announced at the end of June. So, it’s a restoration of that original agreement that I hope stands. It will be important to really move the needle so that transit is a higher portion of the overall proposal. We really hope to see that. I’ll also point out there's some money for high-speed rail as well, which would be important to having a really world-class rail.

Greg Dalton: Carla Frisch, what do you see in the Build Back Better the new plan making its way possibly through the Senate. What are the most important climate provisions you see there?

Carla Frisch: So, there is a significant additional climate and clean energy investments in that Build Back Better Act it really accelerate our progress toward our goals. So, that includes further investment in efficiency both at the homeowner level and the appliance level and also at industrial facilities. There are further investments in resilience and EV infrastructure. And then the really significant piece is the clean energy tax package. So, significant tax credits for individuals shifting towards clean energy and electricity or in transportation and also significant very significant market shaping tax policy for the private sector to really accelerate the investments in solar and wind and many other clean technologies.

Greg Dalton: Right. Sasha, last words things you’re looking for the big climate things in the Build Back Better?

Sasha Mackler: If you’re looking at the Build Back Better bill, that tax package is really the heart and soul of the next step of our climate agenda which is reducing the costs of clean energy technologies for deployment. The infrastructure bill is all about building the technologies and the demonstration projects. The next bill the Build Back Better bill if it passes and gets signed into law will be focused on lowering the cost so we get that deployment of clean energy technologies and the protection of our nuclear fleet through a tax credit that would keep existing nuclear plants open really important for maintaining our footing as we look ahead for decarbonization. And then I think the step after that if we look ahead to 2022 if we could be so bold and think a little bit into the future would be how do we then create the framework for the long term in terms of how do we take advantage of those low costs of the innovation pipeline that were just getting in place. And then are there things like a clean energy standard other industrial policies that really help to channel the energies and the capital in the private sector towards the long-term, which again, I would argue would be net zero by midcentury.

Greg Dalton: On this Climate One... We’ve been talking about what the infrastructure deal means for climate with Sasha Mackler, Executive Director of the Energy Project at the Bipartisan Policy Center; Beth Osborne, Director of Transportation for America; and Carla Frisch, Principal Deputy Director of the Office of Policy at the US Department of Energy.

Greg Dalton: Climate One’s empowering conversations connect all aspects of the climate emergency. To hear more, subscribe to our podcast on Apple, Spotify or wherever you get your pods. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. It really does help advance the climate conversation.

Greg Dalton: Brad Marshland is our senior producer; Ariana Brocious is our producer and audio editor. Our audio engineer is Arnav Gupta. Our team also includes Steve Fox, Kelli Pennington, and Tyler Reed. Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.