Summer Films on Corn, Coal, Lights and Flights

Guests

Rita Baghdadi

Jeremiah Hammerling

Quinn Kanaly and Noel Dockstader

Sriram Murali

Sally Rubin

Summary

It’s a summer movie special as Climate One talks to the directors/producers of four recent documentaries that bring human drama to the climate story: Hillbilly, which explores the myths and realities of life in the Appalachian coalfields; My Country No More, the story of one rural community divided by the North Dakota oil boom; Saving the Dark, which focuses on the battle of dark-sky enthusiasts to fight light pollution; and Point of No Return, in which two pilots risk their lives flying around the world in a solar-powered plane that is as delicate as a t-shirt.

Full Transcript

Announcer: This is Climate One, changing the conversation about energy, the economy and the environment.

From streetlights and solar flights, to coal miners and corn farmers – we’re looking at recent documentary films that bring human drama to the climate story.

[HILLBILLY CLIP]

[POINT OF NO RETURN CLIP]

[MY COUNTRY NO MORE CLIP]

Announcer: With insights from the filmmakers.

Rita Baghdadi: Our film is really about neighbor versus neighbor. We never wanted to make a David versus Goliath kind of story.

Announcer: Climate-conscious films for the holidays. Up next on Climate One.

Announcer: Welcome to Climate One – changing the conversation about energy, economy and the environment. Climate One conversations – with oil companies and environmentalists, Republicans and Democrats – are recorded at the Commonwealth Club of California, and hosted by Greg Dalton.

I’m Devon Strolovitch. Climate change is sometimes called the anti-story because the end is uncertain and far in the future. But several recent documentaries tell climate-related stories with real human drama. On today’s show, host Greg Dalton talks to the directors and producers of four of these films – beginning in coal country.

[HILLBILLY CLIP]

The documentary Hillbilly, directed by Ashley York and Sally Rubin, is a personal and political journey into the heart of Appalachia, exploring media representations of rural people while showcasing the diversity of communities throughout the region. The film includes Ashley’s visit with family in her Kentucky hometown on Election Day, 2016. Greg Dalton spoke to Hillbilly co-director Sally Rubin, and began with this basic question.

Greg Dalton: What is a hillbilly?

Sally Rubin: That is the question that the film seeks to answer. Having worked on this project for 4 1/2 years I would say the reclaimed definition of the word which is what we seek to project in the movie is somebody who is usually from the mountains who identifies with family, culture, storytelling, good food, good music, appreciating life.

Greg Dalton: The film talks quite a bit about how popular perception of hillbillies was shaped by shows such as the one that I watched a lot growing up, Beverly Hillbillies. So how has Hollywood shaped our common perception of people in Appalachia?

Sally Rubin: Well Appalachia is a place that, you know, Hollywood portrays it to be, and it is in truth fairly remote. It’s hard to get there coming from L.A. it takes a full day, sometimes more. There's no direct flights into the heart of the coalfields. So, you know, it’s a place that most people haven't been to or most urban people I should say, most people not from that region haven't been there. So people rely on Hollywood and media depictions both films and television but also books, articles, postcards to develop a sense of what people there are like. And from very early on, certainly from the 50s and 60s in Hollywood and even from much earlier there's been an image that has come out of those media, you know, out of film and television that has depicted the hillbilly as one of sort of several archetypes as Ashley and I my co-director and I worked on the film. We were able to identify several key “hillbilly” archetypes that movies in Hollywood have really used. There's the ignorant hillbilly so of course, Beverly Hillbillies is a perfect example. There is the sociopathic barbarians such as you would see in a film like Deliverance. You’ve got the meth addict like Pennsatucky in Orange Is The New Black. You’ve got the Welfare Queen, Pennsatucky also is an example of that. So there's those key archetypes in Hollywood has sort of use those and recycle those images again and again and again for its own benefit really.

[HILLBILLY CLIP]

Greg Dalton: And there’s a point in the film that the people there are not of value. So it's a good place to put a dirty energy operation such as coal. It’s full of trash so why not trash it, one of the people says. So what's the connection between the hillbilly culture and coal?

Sally Rubin: That's a really good question. And that, you know, making that connection between hillbilly culture and coal and sort of making that point. I mean coal central to the identity of the people there. Even if your parents don't work in coal, coal is in the lifeblood, it's in the history, it’s in the veins of that entire region. The region really was built on the backs of coal. They call it King Coal. So, yeah, it’s very, very complicated. People there during the election, we were there filming as you see in the movie we were in Eastern Kentucky filming in the heart of the coalfields the night of the election, the presidential election. And people were very hopeful that President Trump could deliver on his promise to create jobs and keep coal alive in a climate where the fear is that the lifeblood is going away not just temporarily but for good.

Greg Dalton: And how is that working out the revival of coal that President Trump promised?

Sally Rubin: Well there’s certainly been a pullback on a lot of the key laws there. A lot of the laws that protect for instance the watersheds there used to be a rule that you could only dump coal sludge within so many feet above a waterway. There has been a real change in some of those but that hasn't brought back the jobs. The jobs are on their way out and we have not seen a huge difference and you do not see that promise sort of coming to fruition. And people there I would say already many of the folks in the coalfields are feeling somewhat disenchanted by that. I think when Trump said we’re gonna bring back the jobs we support coal. What's so important is that people there felt like he supports me. So in many ways just having that validation just being told that you matter when so many people, including, I daresay, but including Hillary Clinton were saying in many ways that those people don't matter. They're all deplorables, we’re gonna eliminate coal jobs, you know, that sends a message that you don't matter.

Greg Dalton: Right. There's one point in the film where one of the commentators is talking about sort of the cultural politics of people in coal country on the left, there's this stereotype of viciousness that they’re all poor and uneducated with crooked teeth. And on the right, that they’re salt of the earth white working class that plays into our national politics it seems and you got at that.

Sally Rubin: Yeah, yeah. I’m glad you picked up on that. I mean that's honestly possibly my favorite moment in the movie. It's just, that's Barbara Ellen Smith, she articulates that point so well,

[HILLBILLY CLIP]

Sally Rubin: You know, we never set out when we were making this film to criticize how the Democrats were running a national presidential campaign. We started making this movie in fall of 2013 before Donald Trump was on anybody's horizons. We just we’re making a film about the history of hillbilly stereotypes in Hollywood. But then the election happened and so many angles and kind of depth Scott added to the film including that point. And, yeah, I think in many ways it's the most powerful take away for the movie.

Greg Dalton: So do you see the argument that the left forgot about a lot of people Democrats forgot about a lot of people in the interior part of the country. And people in Appalachia being, you know, perhaps first and foremost among that?

Sally Rubin: Yeah and this circles back to why I personally wanted to make the movie in the first place. I'm not from Appalachia. My mom's from the mountains of East Tennessee so I have some personal connection there. My roots are based in middle-class liberal New England, I’m from Boston and I always hated even as a teenager going way back I hated the hypocrisy. I would go to parties and be talking to my liberal Boston friends who would never be caught dead saying the N-word or any other racial slang, you know, slangs about sexual orientation. But here, they would throw around the terms poor white trash, redneck and hillbilly. They were okay putting down poor white rural working class people. I always hated that that hypocrisy always drove me crazy and it drove me crazy in this past presidential election when I saw it happening again on a national scale where the stakes were really high.

[HILLBILLY CLIP]

Greg Dalton: Tell us about Shelby on election night and who she is. These are members of the family that voted for Obama and then Trump.

Sally Rubin: Yeah. So Granny Shelby lives in Central Eastern Kentucky. And she's Ashley’s grandmother they've always been incredibly close I think in many ways Granny was critical to raising Ashley. But she and her family members they are in Eastern Kentucky in spite of having voted Democrat for most of their lives actually went and registered as Republicans so they could vote for Trump. Something called to them and clicked for them about who he was what he was saying. Going back to what I said before I think that they felt heard and acknowledged by him in a new way that they’ve never felt before from a politician. They said, Ashley’s Uncle Bobby in the movie says we've always been forgotten and here's someone who’s listening to us, so why not vote Trump.

Greg Dalton: And yet they’re still loving this family, politics is not dividing that family, they’re still loving that family.

Sally Rubin: Yeah, that's part of what I love about that family and Ashley's relationship with her family. That's part of who Ashley is. That family functions as a microcosm of what we would like to see in America, and of course we’re not so Pollyanna as to believe that tomorrow all Democrats and Republicans are gonna go hug and make jokes and be super affectionate with each other. But gosh I hope on some level that there can be a sense of humor and a sense of perspective about all this. And I really hope that the film can help to get people from both sides of the aisle thinking about each other's point of view may be talking a little bit maybe laughing a little bit. I hope that's not too much to ask.

Greg Dalton: So what's the future for someone who's in the coal industry. I remember I interviewed Maria Gunnoe who’s a coal miner's daughter in Appalachia. Her son is working in the mines, but he is training to be an emergency medical technician to have a new career outside, you know, third-generation coal worker trying to have a career outside of coal. What are the pathways, if any, for people to get out of coal if they see that as a declining industry?

Sally Rubin: That’s a good question. You know the folks that we know who are working in the region a lot of them are in education. Every community, no matter how small, no matter how remote needs teachers, good teachers, people who are educated. Certainly there are plenty of really wonderful universities throughout the region so there's always higher education there. You know, there's of course some tourism I think one of the hopes is that there's just not gonna continue to be such a kind of “brain drain” this idea that anybody who is from Appalachia who’s smart needs to leave in order to make something of themselves. There's a huge movement now in the region of people who are working to keep the smart, talented folks there and let them work on, you know, movements around farming, sustainable farming and agriculture, wind energy of course, you know, activism. There's just a huge, and the film hints at this movement some of it is in there. You see the Appalachian Media Institute portrayed and they are a group of young media makers some of them queer who’ve come from the mountains were learning about making documentaries how to tell their own stories. So yeah there's a huge effort, both from insiders and to a certain extent, outsiders in the region who are working to kind of create some kind of alternative economy there for people who can't sustain a career in coal anymore.

[HILLBILLY CLIP]

Greg Dalton: Well Sally Rubin, thanks for your time. Thanks for coming on Climate One.

Sally Rubin: Alright. Thanks so much.

Announcer: Sally Rubin, co-director of the 2018 documentary Hillbilly. Coming up, Greg Dalton asks about the oil drilling boom in another rural community, and talks to the director of a film about saving the dark night sky.

Sriram Murali: People living in the cities are lost in their busy lives without much care for the view of the stars and I feel that our lives become less meaningful because they don't understand that we’re part of something much, much bigger.

Announcer: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Announcer: You’re listening to Climate One and we’re talking about recent documentary films that tell the human side of the climate story. We go now to one of the most rural communities in the country: Trenton, North Dakota.

[MY COUNTRY NO MORE CLIP]

Announcer: My Country No More, directed and produced by Rita Baghdadi and Jeremiah Hammerling, tells the story of a new American oil boom, and the ruptured community left in its wake. Greg Dalton spoke to Rita and Jeremiah about the film and the people it profiles.

Greg Dalton: Rita tell us about Kalie Rider. She’s a school dietician who’s trying to protect the land where she grew up.

Rita Baghdadi: Yeah. So Kalie, she went away to college and she was ill she tore her ACL and she had a surgery. She had to move home and around that time that's when the boom started. And so she moved home because she felt, you know, she needed to be closer to family in order to get better. And it kind of turned out that her community needed her just as much as she needed her community because, you know, when all this started not a lot of people were speaking out against it.

Greg Dalton: And what’s Kalie trying to do. Let’s set the stage here. She’s trying to protect the church from being in the shadow of an oil refinery.

Rita Baghdadi: Yeah. So the church land is owned by the Onnie [ph] family, Dwight Onnie [ph] and his father pass it down to him. And there was a stipulation that said as long as the church was active within the community that it would stay with the community. So because, you know, oil boom the price of the land, Dwight sold all the land around the church for a diesel refinery. So Kalie wanted to, you know, make sure that it wasn’t gonna be like you said overshadowed by a diesel finery or even bulldozed to make room for diesel refinery. So she's really fighting against the land around the church.

Greg Dalton: Jeremiah, you have a personal connection to the church and even directly to Kalie.

Jeremiah Hammerling: Yeah. So I was actually born around the same area where Kalie and her family grew up and my dad was the pastor at that church and another church in that area during the 80s. And it was a tough time out there so he got to know the community quite well while I was just a child. And then, you know, as we moved later kept in touch with them. So when we heard that the oil boom had happened the most recent one kind of in the late aughts, you know, 2008, 2009. We wanted to get out and see what was happening and we’ve been looking for a way to tell stories in those spaces. I think that when you get to rural places it’s so vast and empty. And then when you talk about industrializing those spaces rapidly whether that’s an oil boom or other sort of industrial interest that can sometimes feel like they’re popping out overnight. A lot of people like from urban areas, sometimes can’t quite wrap their heads around it. They’re like, well, you know, there’s so much room it seems like a good place to do it, you know. But initially that was what drew us to the story. Kalie called my dad and she was like the whole town is going up in flames and some reason you’ve got to come out here and see this. And so I think, you know, the film became a kind of interesting bearing witness to seeing a rural space slowly the domino effect of just one piece of land being rezoned and these, you know, small fights with county commissioners and neighbors against neighbors. And then you could just see over time how, you know, a rural area could become an industrial zone.

[MY COUNTRY NO MORE CLIP]

Greg Dalton: One of the interesting characters is Ruben Valdes who is a Native American who give someone a ride to North Dakota who offers to pay gas on a job when you got there. So tell us more about Ruben.

Jeremiah Hammerling: Yeah, it was – so very early on when we were there which was around 2010, in the winter 2010. There had just been a number of huge reports on, you know, national television, radio that, you know, of course this is after the great recession 2008 a lot of people were out of work and all of a sudden boom the oil hits North Dakota. And all these people out of work tradesmen were flooding to the area. Now what they didn’t say on those reports is that there was nowhere to live. So over practically overnight you have a quarter of million people that are showing up looking for work, but with nowhere to stay. So we had heard that, you know, there were hundreds if not, thousands of people staying at the Walmart parking lot. And sure enough we go out there and it’s very cold night like 20 below and we’re freezing of course we didn’t have to stay in the Walmart parking lot and we start interviewing people. And before we leave and we’re absolutely freezing, we bump into this guy Ruben. And there was something about his spirit that we’re like, oh man, this guy is really interesting and just as vibrant guy. And we had no idea at that time that we’d be following him for five years and, you know, in a way I mean it sounds harsh but I think he would agree he kind of became a canary in the coal mine a little bit where, you know, he was the workforce. And so there was a time where he was homeless and he was down and then the work hit and then he was, you know, making six figures and doing great. And then, you know, what we document in the film is how, you know, booms go boom. And what happens after, you know, it's bound to be a bust. And so, you know, later in the film, Ruben is unemployed and now he’s doing okay but, you know, it was interesting to see both sides. To see it from the community that had been there for a while and then the new community which is part of this, you know, influx of the workforce the fabric of that infrastructure, the human infrastructure that kind of makes it all work.

Rita Baghdadi: Yeah, I mean Ruben, we love Ruben because he’s so positive but also because he really represents the question we were sort of asking is like what are we willing, what and who are we willing to sacrifice in the name of progress. And, you know, Ruben really represents that the sort of human sacrifice of progress because you sort of offer your body up to being, you know, a miner whether it's uranium mining in the 70s in Wyoming or it's, you know, fracking for oil and gas in North Dakota in the 2000's and, you know, really takes a toll on you. And his health has really suffered because of it. So he’s sort of the human, you know, human sacrifice for that.

Greg Dalton: Spin out a little bit that theme of progress because it's a central tension in the film is progress is new jobs, new construction, not keeping things the way they are.

Rita Baghdadi: Right.

Jeremiah Hammerling: It’s still a pretty conservative area and they're very pro-oil for the most part I would say. I think that might’ve, you know, people's opinions might have changed a lot now having lived through this last boom. And even now, as oil is coming back making a comeback and there's more production, more wells are coming back not overnight. Now they're talking about slowing down production because I think they realized that –

Rita Baghdadi: It’s not sustainable.

Jeremiah Hammerling: -- it wasn’t sustainable. Part of the reason that North Dakota blew up was the regulations were so minimal, at least initially. I mean the Bakken play or that they call like that whole area there’s a huge area covers part of Eastern Montana and Canada. But there were just wasn't nearly as much attention on those areas because they were, North Dakota was a spot that was unregulated which is partially why it blew up overnight I mean one of the things that we try to play on and hopefully it's not heavy-handed. I think, you know, in the film is that really it is an open ended question. I mean what is the idea of progress like I mean we do use oil whether it's modes of transportation or the clothes on our bag or, you know, other forms of infrastructure.

Rita Baghdadi: Food. Yeah.

Jeremiah Hammerling: And so I mean it’s a valid question. And if we’re gonna continue this, you know, how do we segue, how do we find alternative means of cleaner energy, et cetera.

[MY COUNTRY NO MORE CLIP]

Greg Dalton: Roger Bierce is a farmer who sold some land for what he thought was and his wife thought was gonna be an ethanol plant. They considered to be continuing to support farming turning corn into fuel and then he has some regrets.

Jeremiah Hammerling: Yeah. I mean in a way here’s a guy who, you know, part of the family, Kalie’s uncle, just a modest, hardworking guy who’s been in the area for a long time and, you know, thinks he’s doing something that’s gonna support local agriculture. Now whether or not you think ethanol is a very great idea is, you know, like here nor there but the point being that it would have supported like crops that they could have had. And, you know, flash forward and this turns into a rail port which turns into a reason to say hey this is how we could offload oil, this is where and then ultimately, it becomes one of the six access points for the Dakota Access Pipeline. So when Standing Rock is happening, you know, 250 some odd miles upriver it’s all very quiet and this is where the pipe is one of the places that it’s starting. And so serendipity would not be the right word, but we certainly weren’t planning on being able to show how these tiny decisions could lead into something that had at least captured, you know, the global consciousness at that point.

Greg Dalton: You didn’t talk to an energy supplier. I wonder, you know, Ruben, you said is sort of the voice of the person who gets a job by going up there and does pretty well for a while and then he gets laid off. So I’m curious where is the voice of the energy supplier saying hey, our country runs on the stuff we need this. Is that intentional or do they not want to talk?

Rita Baghdadi: Mostly they don’t want to talk. We weren’t that concerned when we kept getting nosed because we really like, our film is really about neighbor versus neighbor. We never wanted to make a David versus Goliath film because that story has been told. And, you know, our film does have elements of that but we wanted to make more of a David versus David because really, the people that are fighting for this refinery, our local people like the neighbors like Dwight and Steve they live there and they want the refinery and their next door neighbors don't. So we wanted to make more of a neighbor, you know, not a big oil producer versus the little guy kind of story.

Greg Dalton: And at the end tell us the church is in place, the refinery wasn't built. Where does it stand?

Rita Baghdadi: Yeah. So they continue to try to build the refinery. And they've actually tried to build that second rail port more than once. They continue to drill out there but the church still stands. Kalie still plays music at that church and, you know, the neighbors still go.

Greg Dalton: And some people have cashed out made some money, other people feel like their town’s been spoiled.

Rita Baghdadi: Yup. I mean, there are people that really do believe that refinery is definitely gonna get built. It’s just a matter of time because they’ve already laid all the groundwork in terms of permitting and, you know. Only time will tell, I think.

[MY COUNTRY NO MORE CLIP]

Announcer: A clip from the 2018 documentary My Country No More, directed by Rita Baghdadi and Jeremiah Hammerling. You’re listening to Climate One, and we’re talking about recent documentary films that bring human drama to the climate story.

Rural North Dakota is still a great place to see the Milky Way and the millions other stars in the night sky. But in many cities, light pollution increasingly prevents people from seeing beyond our own celestial orb.

[SAVING THE DARK CLIP]

Those are excerpts from Saving the Dark, which shows the effects of light pollution on astronomy, human health, wildlife, and beyond. It also shows the work of nonprofits fighting to preserve dark night skies. Greg Dalton spoke to director and producer Sriram Murali and asked him to define his subject.

Greg Dalton: What is light pollution?

Sriram Murali: Light pollution is any light that goes where it's not supposed to go. It's any excessive light. Fighting light pollution doesn't really mean you got to turn off all the lights. The dark sky enthusiasts and the dark sky advocates are fine with people lighting up before Christmas for a month and then just turning it off just being mindful of the environment and how it affects everything around us.

Greg Dalton: And a lot of your film is about these dark sky enthusiasts who are concerned about the loss of being able to see the stars not something that city dwellers think a lot about. What’s being lost if there are some light pointing toward the sky. What are we losing?

Sriram Murali: The night sky reminds us of our place in the universe. The universe gives us perspective it gives us a connection a sense of belonging. People living in the cities are lost in their busy lives without much care for the view of the stars and I don't really blame them because they don't really know what's up in the sky. And I feel that our lives become less meaningful because they don't understand that we’re part of something much, much bigger.

Greg Dalton: Part of the film is about LED lights, you know, most light bulbs incandescent light bulbs Thomas Edison would recognize and yet LED lights are thought of as an energy-saving practical innovation to reduce greenhouse gases, reduce energy loads. Are they bad?

Sriram Murali: They are the bane and boon of light pollution, LEDs to put in a way. If about a decade ago, LEDs of very high color temperatures the 4000 5000 Kelvin were the only ones that were efficient and economical. But these LEDs of really high color temperature called the blue light is very harmful not just to our eyes but the wildlife and it suppresses the secretion of melatonin, the hormone responsible for our sleep-wake cycle. So but in the last couple of years technology, the LED technology has grown so fast that now a 2700, a 3000 Kelvin LED light bulb is as efficient as a higher color temperature one. So if it the right color temperature use and if it’s shielded, it can help not disrupt the night time environment. In fact, San Francisco just did that, they changed most of their streetlights from sodium-vapor to dark sky friendly LEDs and people have been liking it so far.

Greg Dalton: And often the concern is about safety. So there's one person in the film talks about adaptive controls kind of smart buildings where lights turn off when people are not there they turn on if someone's around. So is it also possible that technology can regulate the use of light so they are not always on?

Sriram Murali: Yeah, definitely. And there’s an example in Tucson. They retrofit and they change all the lighting to dark sky friendly lighting, but they also dimmed the light, reduce the luminosity by 60% after 11 o'clock and people did not even notice the difference. So there's a lot of energy savings and it's not just about the street lighting that all these lights indoors that are on for no reason. So when you have adaptive control they say that you can save more than 70% of the energy.

[SAVING THE DARK CLIP]

Greg Dalton: There's parts of the film that talk about impacts on species and it's not just human impacts of light. How does the light that we’re creating affect bees and bats and butterflies?

Sriram Murali: There’s so much wildlife out there that evolved to this day life cycle for billions of years. And in the last hundred years we’ve disrupted this nighttime environment. Millions of birds die each year colliding into brightly lit buildings. And thousands of turtles in Florida die each year due to artificial lighting behind the beach. And they’re just starting to learn all these how wildlife is impacted and bees and all these pollinators they are deterred by the artificial lighting and scientists have found that it affects pollination by about 60%.

Greg Dalton: And yet for the turtles there are types of lights and minor modifications to over oceanfront properties that can solve the problem.

Sriram Murali: Yeah, the sea turtle conservation in Florida they’ve had a lot of success in the past decade. So there are certain types of LED's that do not affect the turtles. These LEDs are amber in color and they are shielded and very close to the place very close to the ground so that the light does not go towards the beach. And turtles, when they come on shore to nest or these turtles when they hatch and go towards the ocean, they for some reason do not see the amber light and it does not really disturb them. And some people think not knowing how this amber light looks like they think that they lose their sense of security or safety. But in fact you can see much better in sea turtle friendly lighting. People often don't realize that excessive lighting can be a bad thing. It can create a lot of glare and discomfort.

Greg Dalton: Lighting is branding in lots of situations for retail establishments, storefronts. There’s a part in the film that looks at gas stations and how bright gas stations are. What's the solution I mean public education do you think there ought to be rules that have limited lighting because of the pollution effects? You mentioned Tucson and San Francisco and others have done to kind of reduce the city deployment of light, certain types of LED lights. That's different than telling voters you can't light your gas station to a certain point or you can't light your storefront.

Sriram Murali: So The International Dark-Sky Association they are the nonprofit based on Tucson, Arizona. They educate the public and policy makers on the issue of like pollution. They launched a program The International Dark-Sky Places Program that identifies the last remaining dark sky landscapes around the globe. They have about 80, 85 dark-sky places around the world and one of the things that come with the dark sky places all the lighting art and so not just say the National Park or this National Monument that makes sure all these, all their lighting are dark-sky friendly but also the communities and the businesses around the dark-sky. So one of the biggest successes recently is the designation of the dark-sky in Idaho. It is a land of about 1400 mi.² and it's a huge achievement because they had to convince and get the buying of all the communities and businesses around the place and be able to see it as a good way for their business because it attracts a lot of astro-tourism.

Greg Dalton: So there’s a business driver for that. And there’s a part in there that talks about how popular the night sky programs are at national parks. But in a city it's kind of hard to ask a business to unilaterally disarm to light my store at a lower level and the close at another store gonna look more illuminating and I’m gonna lose business. Why should I go first?

Sriram Murali: I don't think not at least the next few decades be able to fight like pollution in the cities or be able to see the stars. It's a very tough problem but at least it'll be a good start of the local municipalities and the local governments and cities start using these lights. And it’s going to be tough, most businesses use light to send attractant, people turn towards light it attracts them. It's gonna be tough for the businesses. They have to have some kind of incentive for example, in Florida the city hall conservancy got a lot money from the Gulf oil spill and all the lighting that it's a free. So these businesses need some incentive and the dark-sky association they’ve been doing a pretty good job and the city hall conservancy have been doing a very good job. And I feel that half the battle for light pollution will be won then people go these starry-night skies for themselves and it is up to individuals to ask for those changes.

[POINT OF NO RETURN CLIP]

Announcer: Sriram Murali, director/producer of Saving the Dark. This is Climate One. Coming up, Greg Dalton asks what it was like to make a film about the first solar-powered flight around the world.

Quinn Kanaly: We wanted this to be very experiential. We wanted to really put you in the cockpit and put you on the team showing a group of people working hard for over a decade to try to come up with a solution and try to inspire the world and put their lives on the line to do so.

Announcer: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Announcer: You’re listening to Climate One, and we’re looking at recent documentaries that focus on the human drama of fighting climate change.

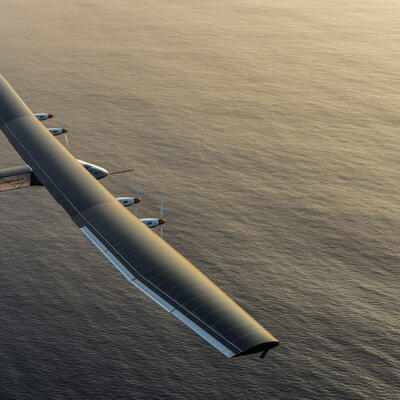

In Point of No Return, two pilots risk their lives flying around the world in a solar-powered plane that’s as delicate as a t-shirt.

[POINT OF NO RETURN CLIP]

Quinn Kanaly and Noel Dockstader, the filmmakers behind Point of No Return, tracked the unfolding drama of this audacious zero-fuel flight both on the tarmac and at mission control. Greg Dalton spoke to Quinn and Noel about the film, and asked them about the pilots and their journey.

Greg Dalton: Tell us about the two main characters and their ambitions and their egos. Introduce us to Bertrand Piccard and André Borschberg. Quinn.

Quinn Kanaly: Sure. They’re very interesting people, very different. I’ll start with Bertrand first. He comes from a long line of scientific explorers in his family. His grandfather was the first, Auguste Piccard, to fly to the stratosphere in a hot air balloon and see the curvature of the earth with his own eyes. And his father was the first to go to the Mariana Trench in a submarine, Jacques Piccard, in the 60s. So he had to begin with a huge kind of burden on his shoulders. He also flew, Bertrand, flew around the earth in a hot air balloon for 21 days –

Greg Dalton: Nonstop.

Quinn Kanaly: Nonstop. And he was on the cover of National Geographic. So he, you know, wanted to be an explorer from day one. But he also wanted to do something with purpose, you know, his parent, his father was into, you know, science of course not just exploration. And so when Bertrand finished that hot air balloon expedition he had this idea like he almost ran out of fuel on that flight.

Greg Dalton: What’s next.

Quinn Kanaly: And, you know, it was stressful. And he said, what if I fly around the world without any fuel. So that kind of came out of this hot air balloon expedition. And so he had this dual purpose of wanting to explore but also wanting to do something with major impact and show the world what might be possible without fuel.

Greg Dalton: Yeah. And so he has this legacy of these pioneers and what can he do that his grandfather and father didn't do. And then there’s the fighter pilot.

Quinn Kanaly: Exactly. André, who had been in the Swiss Air Force for 25 years. Interestingly, also he’s a yogi and he practices yoga and meditation which plays a huge role in this film because it's a solo flight. Each of these two pilots have to take turns flying this solar airplane around the world. And that means potentially a flight for up to five days alone in the cockpit. And so they each had to really mentally train to do this. Bertrand also, I might add is a psychiatrist by profession, not just an explorer. So he had the psychological dimension. He uses self-hypnosis to fall into a deep relaxation, not deep sleep because that would be dangerous. And André uses yoga and meditation to do the same thing and they had to only sleep for 20-minute periods at a time over a 24-hour period that might add up to three hours. But try doing that for five days straight and, you know, that really separates, you know, the heroes from the rest of us.

Greg Dalton: That’s amazing. I didn’t quite get the depth of their background from the film. But it explains one point, Noel, where they’re actually, one of them makes a mistake and says –

Noel Dockstader: Yeah on flight two, from India.

Greg Dalton: So pick us up there and you have these two people who are pushing the boundaries of human possibility and technology and yet their egos come into play, yet they check their egos, at one point he realizes, Bertrand says, “I’m not the best pilot.”

Noel Dockstader: Well, in many ways ego, you know, has to be part of the story because, you know, anyone that has been through really difficult adventure particularly an adventure where, you know, they have had to think for a long time about how much they’re gonna risk their own life for this dream. And the dream is both personal, but it's also both in terms that they feel like they're doing something for a greater purpose.

[POINT OF NO RETURN CLIP]

Greg Dalton: Tell us Quinn about that Pacific crossing, which is in many ways kind of the dramatic climax of the film.

Quinn Kanaly: Sure. So everything builds up to this crossing of the Pacific Ocean. Five days, five nights alone in a fragile airplane that you can poke your finger through that could break apart in mild turbulences and it's an unheated and unpressurized cabin. The pilot has to go from 5,000 feet to 28,000 feet every day on oxygen for half of that time. So it's extremely strenuous for the pilot who does it, in this case, it is André, and dangerous. And they had never actually proven that they could fly this particular plane could fly through the night. Everything is on the edge of the engineering and what was possible. And so they expected maybe 10% of batteries left every morning at sunrise, which as we all know, having cell phones, you know, when we start getting in the red, we start getting a little nervous and looking for the wall plug. But they didn't have that, they had no extra fuel reserves on board and really it would mean, you know, ditching into the ocean the airplane shattering into thousands of pieces and a pilot in a life raft for a few days until a cargo ship found them.

Greg Dalton: Quite dramatic and so they divert to Japan because and then they finally make it to Seattle. So Noel, tell us a little bit about the plane. Quinn described it’s very light, it’s basically featherweight but tell us, you know, it charges during the day and then the battery run down at night. Tell us about the plane.

Noel Dockstader: Yeah. Basically they have as much surface area as they can do without being too exposed to the elements. It still has to fly.

Greg Dalton: Wingspan of a 747.

Noel Dockstader: Wingspan of a 747 and they're getting to the point where if it gets too much bigger because it's so light, you know, that makes it unstable. They sacrifice stability for efficiency basically.

Quinn Kanaly: The weight of a car.

Noel Dockstader: Yeah, it’s the most efficient plane probably ever built. But also maybe the most vulnerable plane that ever crossed an ocean. So in order to make that work they need is to gather as much sun as they could and over the oceans of course, they can't land whenever they want. So they have to know they can make it through the night, so they gather all the energy they can, they climb during the day, they’re climbing to altitude and then about sunset they’re at max altitude about 28,000 feet and then they start to descend. So when they take off they want as much of a full charge they can so they can’t plug into the wall that would be cheating there would be no record for a solar flight around the world although we joked about it a lot because the plug was always right there. But they would take it out into the sunshine for a while and let it sit on the runway to charge up. And of course they have to be very careful there too because too much sun will toast the cells. And if you burn one cell because all the cells are connected, you’ve kind of blown the lot.

Greg Dalton: It’s like Christmas tree lights. If one goes out then the whole thing is shot.

Noel Dockstader: Yeah. And so, you know, it's their baby and they’ve nursed this thing for 13 years, both from a technological point of view. But these engineers, you know, the way they touch it is just so careful they’re just everything about it because they know that it won't take much to be the end of the adventure. And in many ways the plane had a persona for them. You know the plane was not just nuts and bolts and all of that. It was something that they had poured so much of their hearts into so much of their hopes, their dreams, their courage everything that you can only imagine that when it took off and it goes out over that ocean how they're feeling.

[POINT OF NO RETURN CLIP]

Greg Dalton: Quinn, one thing that isn't in the film and is in a lot of documentaries there’s a lot of statistics and figures, and there's no kind of, you know, shame or guilt about people flying it. So tell us about the connection of what’s really motivating them. Clean energy and climate change is clearly a backdrop here and it’s motivating them to take these tremendous risks.

Quinn Kanaly: Yeah, we set out sort of not to do that as filmmakers I mean we talked about it and we said how much do we want to put that in. We wanted this to be very experiential. We wanted to really put you in the cockpit and put you on the team showing a group of people working hard for over a decade to try to come up with a solution and try to inspire the world and put their lives on the line to do so. And show what we can do in the air as Bertrand says we can do on the ground and that is our message. They wanted to inspire people around the world as they touchdown in all these cities and had meetings with schoolchildren in every country and were constantly on a podium kind of communicating their message and talking to CNN and BBC and everybody that all of these energy efficiencies in the air. They had electric motors that were 97% efficient. They had extremely lightweight and energy-efficient insulation like none other on the planet that’s now being employed into refrigerators you know, very thin solar cells and carbon fiber you name it. All of these things we can do in our cars in our homes in our daily lives to, you know, lessen our carbon footprint and collaborate and come together and get as Bertrand says get off, you know, your seat and do something.

Greg Dalton: Right. And I interview a lot of climate evangelists who admit that their carbon sin is flying around on airplanes and aviation is thought to be kind of out of reach may be biofuels. And yet André says at the end of the film, Noel, 50 passenger airplanes in 10 years running on batteries.

Noel Dockstader: Yeah, every trip potentially is kind of a guilt trip. That's true. But the good news is electricity is you can leave climate change, even out of the political argument or whatever you want to do. You know, we were in certainly in Middle America and going through the birthplace of aviation. We were in Tulsa and we were, you know, crossing the area where human ingenuity figured out how to get us airborne in the first place. And you know there's a lot of people there that may not be sold on the science of climate change and you know, fair enough it’s not exact yet. But they certainly appreciated that plane they certainly appreciated the ingenuity of an electric engine. They appreciated the fact that it didn't throw off heat like a bad radiator. And they appreciated that the engineers and the work that went into that, you know, we’re crossing the heartland of craftspeople and in common sense and it appealed to them in a way that may be other environmental initiatives wouldn’t.

Quinn Kanaly: And the thing is of course it's better for the environment without CO2 emissions. But it's also quieter around, you know, there’s noise pollution around airports and then also potentially cheaper to fly from, you know, San Francisco to L.A. or we were just in New Zealand, you know, Wellington to Auckland or whatever on this, you know, smaller flights. These are not 747s right away until we have major revolutions in battery technology. But certainly in the next few decades these planes will be taking, you know, small commuter flights around the world.

Greg Dalton: So you both done some doomsday documentaries. This was a more optimistic human yes we can do this –

Noel Dockstader: Yeah, we were ready for that.

Greg Dalton: Ready for that. Yeah, so how are you feeling after doing, you know, extreme ice survey and other things, how does this one make you feel about our hopes for crack in the climate challenge?

Quinn Kanaly: Yeah, well I mean those were great films to work on as well. But as I sort of mentioned before this was exciting to us in a different way, in that it was really potentially inspiring to people because it showing people of doing something. I think we can all easily get overwhelmed by the weight of the problem in front of us, particularly climate change. It is such a massive problem on a global scale. It requires so much innovation and collaboration, you know, globally, but then on all these different levels on the human individual level but on a governmental level and then pan-governmental level. So it's daunting and so I think this story, you know, was refreshing in a way to kind of look at people doing stuff, but also it was as you mentioned a real adventure like a real 21st-century adventure where we had no idea how it was gonna turn out. And we had to kind of take the plunge with them as filmmakers, not knowing if the plane was going to make it two legs to India whether we’d have a film in the end, it could've ended in tragedy we had no idea. And that's the kind of a new type of filmmaking for us where this really could've ended in many different ways.

Noel Dockstader: It’s fantastic. I mean you live for this documentary makers. You know André said it, you know, we can talk about it a lot, but you know if you don't do something the world will dictate to you, not the other way around. And it's quite simple, that’s true.

Announcer: Noel Dockstader and Quinn Kanaly, the filmmakers behind Point of No Return, the story of the first solar-powered flight around the world. We also heard about preserving the night sky in Saving the Dark, neighbors living through the North Dakota oil boom in My Country No More, and the myths and realities of life in the Appalachian coalfields in Hillbilly.

To hear all our Climate One conversations, subscribe to our podcast at our website: climateone.org, where you’ll also find photos, video clips and more. If you like the program, please let us know by writing a review on iTunes, or wherever you get your podcasts. And join us next time for another conversation about energy, economy, and the environment.

Greg Dalton: Climate One is a special project of The Commonwealth Club of California. Kelli Pennington and Sara-Katherine Coxon direct our audience engagement. Tyler Reed is our producer. The audio engineers are Mark Kirschner and Justin Norton. Anny Celsi and Devon Strolovitch edit the show. I’m Greg Dalton, the executive producer and host. The Commonwealth Club CEO is Dr. Gloria Duffy.

Climate One is presented in association with KQED Public Radio.