The Road to Paris: Christiana Figueres and William Reilly

Guests

Christiana Figueres

William K. Reilly

Summary

Past conferences have failed to reach consensus on addressing climate change. Can the Paris summit produce a lasting, effective and equitable solution?

Christiana Figueres, Executive Secretary, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

William K. Reilly, Senior Advisor, TPG Capital

Full Transcript

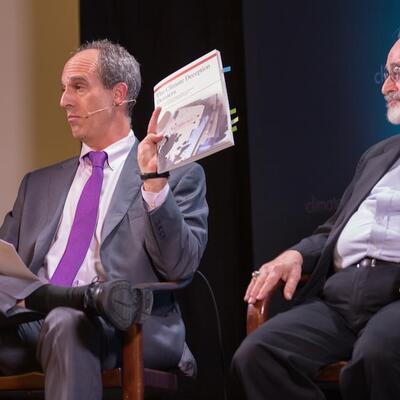

Greg Dalton: I’m Greg Dalton. And today on Climate One we’re talking about the possibility of a global deal to fight climate disruption. Leaders from nearly 200 countries will meet in Paris in December to try and agree on different paths for growing the economy and cutting carbon emissions. Past efforts have fallen short but this time large corporations including some of the world’s biggest oil companies are calling for a meaningful agreement on carbon emissions. Pope Francis recently joined the fray coming out strongly for action on climate change in his encyclical on the environment. Over the next hour we will look at international and domestic politics of energy, the price of oil, the promise of clean technology and other questions from our live audience at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco. We’re pleased to have with us two distinguished guests. Christiana Figueres is executive secretary of the United Nations climate negotiations, will play a central role in the Paris Climate Summit later this year. She’s been deeply involved in climate diplomacy for 20 years, first on the Costa Rica negotiating team and now at the UN. Bill Reilly was chief of the U.S. EPA under the first President Bush. He later served on the board of oil company ConocoPhillips and President Obama appointed him to co-chair the National Commission that investigated the BP oil disaster in the Gulf of Mexico. Bill Reilly is also a member of the Climate One advisory council and a financial contributor to this program. Please welcome them to Climate One.

[Applause]

Bill Reilly, let’s begin recently, almost a quarter of century ago you took President Bush to the Rio Summit that created the United Nations climate convention on climate change. Tell us what happened there and then we’ll get Christiana in terms of what’s happened recently. But take us to Rio in ’92 and set the foundation.

Bill Reilly: Well, you know, I don’t think there was an issue - and the Clean Air Act maybe was an example of one -- where there were more high level reviews, meetings, debates. I debated the budget director, I debated Boyden Gray, an advisor of the President, on the pros and cons of the science, the politics, international relations of climate change. And President Bush decided to support and sign the climate convention which he did and was the first developed country to do so in Rio. At that time, there was a great debate about whether the convention itself was sufficient without a very specific set of metrics, of goals that we would try to achieve in terms of reduction of greenhouse gases. And the President decided that the support was not sufficient for that, he was also in the middle of an election campaign. But characterize the treaty as creating a moral obligation to reduce our greenhouse gases, to reduce them to the level of 1990 without creating a legal obligation. Later, of course, the Kyoto Protocol, protocol of the convention, came along and that did create what was called or considered a legal obligation. It didn’t make much difference because many countries did not come even close. Canada I think is 35% over the goal, Netherlands was 11% over, United States was about 11% over although it had not ratified the protocol. So the climate things had changed but essentially we treaded water for most of the ‘90s on this issue and even since in my view. What was really different about the moment in 1992 was that we had models.

We had the preponderance of scientific opinion predicting climate change, predicting warming and all of the associated issues, drought and excessive rainfall and all the rest. We didn’t, however, have the experience of it. Now we do. That is a big change, whether it’s in Alaska or the drought here in California, the melting glaciers, the evidence is all around us that it’s no longer a theory, it’s no longer a matter of models. It’s upon us. And it seems to me now it ought to be much easier to create the consensus that gives us serious policy.

Greg Dalton: So Christiana Figueres that takes us to Paris. We now have the experience that’s been framed as a moral issue. Kyoto didn’t work out so well. What’s going to happen in Paris, what’s at stake?

Christiana Figueres: Well, I think you pick up from what Bill said. I think the huge difference is that while in the past with the convention, and I would actually argue even the attempt that was made in Copenhagen 2009, I think the implicit assumption was that the problem was in the future and we don’t know if we have the solutions. And I think what has fundamentally changed is that the problem is no longer in the future, the problem is in the present and furthermore the solutions are in the present. So we do have the technologies. We have the capital, we have a growing number of regulations and legislations in place. And we have a very interesting good mood developing internationally that is basically saying, okay, actually, we are going to get to an agreement. So quick correction on your introduction, it’s not the possibility of a climate deal that we’re going to Paris, we are going to get an agreement.

[Applause]

Quick correction there. The conversation now is not are we going to get to an agreement but rather how are we going to do this.

And the complexity is actually now the challenge. It’s not about managing resistance, it’s about managing the complexity, how do you bring all of the components into a coherent whole which above all, bottom line, that agreement needs to potentialize collaboration across countries, inside countries across the different levels, across sectors. It’s about how do you maximize collaboration. Because I think the universal truth has now become very evident. We’re all better off with climate action ASAP than without. So the question now for Paris is how do we do that?

Greg Dalton: And do fossil fuel-producing countries realize that, the Middle East, Russia, petrostates, are they on board with this? Because they have a lot -- some people in those countries are very powerful, they have a lot to lose potentially from putting a price on carbon or moving away from fossil fuels.

Christiana Figueres: Well, but they also have a lot to lose if we do not arrest climate change. The Gulf states, Saudi Arabia and its neighbors, are already among the hottest countries in the world, they cannot afford, you know, to get even hotter. They’re already among the most water insecure countries in the world. They cannot afford this risk. So you do have a very interesting shift where you have on the one hand Minister Al-Naimi, Minister of Energy of Saudi Arabia, saying just two weeks ago in Paris quite publicly, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia understands that oil is not going to be the final solution, that it’s not going to be with us forever. Period. Next sentence. We don’t know how long that’s going to be, whether it’s 2020, 2030 or 2040. We’re talking about relatively short time periods in which someone who led OPEC, who led Saudi Aramco, who is the minister of energy, is really understanding that it is in their own interest to begin as they already have, to invest in the only resource that is even more prevalent than oil in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: the sun..

Greg Dalton: And they’re doing some things there so tapping the sun in Saudi Arabia. Bill Reilly, your thoughts on the transition of these energy dependent states. Are they going to resist this transition or like Christiana just said, trying to get out ahead of it.

Bill Reilly: I would expect that the fossil fuel-dependent states will try to slow it down. I would imagine that they will look through a transition that’s longer than we would consider desirable or then science would suggest and they may be successful at that. Christiana and I were at a conference in Svalbard Peninsula in Norway last year and of the people present there was the representative of the government of South Africa. He made it very clear that South Africa is very committed to coal, that’s what they’ve got, that’s what they’re going to continue to have and was quite defensive about maintaining that position. I think that India will be a slow place to accommodate to a coal-free future, for example. And China, of course, itself has major coal dependency. However, you know, I think that the example of the United States has got to be compelling to a number of people. If you look at how rapidly we have transitioned from a 50% to somewhere in the 30% dependency on coal-fired power for electric utilities, it shows it can be done. And now is a very good time to do it. The U.S. EPA is taking advantage of the alternative, the low price of natural gas, to really drive this change and economics are supporting policy. That’s the time to work, to operate I think. And one hopes that we will see similar developments in some of the other countries.

I also wouldn’t expect that, I know we’ve been disappointed that Australia abandoned its approach to a carbon tax, I wouldn’t be surprised if the impact of climate change itself in some of the extreme events that are expected to be associated with it, don’t drive change faster in some of the fossil fuel-dependent countries that at the present time consider that it’s in their interest to maintain status quo.

Greg Dalton: So cheap natural gas is driven by fracking. So Christiana Figueres, is fracking a good thing if you want to get the world off coal, which is the dirtiest of fossil fuels?

Christiana Figueres: Well, I think you have to see this as a gradual progress here, you know, and sorry about using the same word twice. But this is about avoiding abrupt changes. Nobody is benefitted by continuing a business model, a country model, an economic model that drives us to a very dangerous edge. It’s about, yes, these companies - I fully agree with Bill -- these companies, these countries want to have time to transition. You can’t blame them. Everybody needs time to transition. It’s about the collective good and the collective wisdom about organizing, setting a new direction now so that we can then begin to transition in a thoughtful planned way instead of having abrupt changes that are of no interest to those countries, to those corporations, to anyone. And in that sense, oil and gas does represent an interesting transition fuel if they invest now into all of the technologies that will bring down even the emissions from oil and gas. They have to step up to the plate.

Greg Dalton: Russia is also a state that’s very dependent on natural gas. They’ve submitted their plan. Is it an aggressive plan? Because Russia is at odds with the United States a lot of these days, is it going to play ball and be supportive in this content?

Christiana Figueres: You know, the fantastic thing about this and it’s honestly nothing short of miraculous is that there is not a single country, Russia included, that is not playing ball.

Yes, they’re all playing the ball to their own interest, that’s what they have to do. But there’s no country that has said they want to be exempted from this agreement. In fact, all of them understand that it is in their interest to cover everyone. By definition that’s going to be a complex agreement. Russia has presented it’s INDC (Intended Nationally Determined Contributions), so have 39 other countries.

Greg Dalton: That’s their plan.

Christiana Figueres: Their plan, thank you, their carbon management plan, thank you. They have presented their carbon management plan together with 39 other countries. I, you know, cannot stand here and say anyone of those is absolutely, you know, the best ambition that could have been put on the table. That is not so. In fact, we already know that the sum total of all of those carbon management plans, of which we expect to get at least two times as many by the time of Paris, the sum total will not put us on the path of staying within the below two temperature goal that governments have agreed to and that science has suggested. So part of the complexity of the Paris agreement is, how do you construct something that receives and acknowledges all of those carbon management plans as being a baseline, a first step if you will, but also how do you construct the way forward that treats those only as a first step, as a down payment if you will, and then takes everyone together in an increasing collaborative manner toward the final ultimate destination which is the very difficult but absolutely necessary balance between the greenhouse gases that we will have and the natural absorption of the planet. That is very difficult to attain and even difficult to conceive right now that we would get to that point. But it’s the only way out.

Greg Dalton: Bill Reilly, enlightened self-interest is going to bring Russia and other states to really do as much as possible here?

Bill Reilly: I think you put your finger on something that’s important to them and that is sustaining their gas production and sales. They do have very large supplies. They do also have significant oil deposits and yet the impact of very high temperatures I think was it two or three summers ago, carried off tens of thousands of people. Deaths associated with heat stroke in Russia. Obviously, the Russians are smart people. They have a National Academy of Sciences, they’re monitoring the same kinds of changes and they’re watching what’s happening in their own arctic. So I think that if a way is found for them to make a transition that is gradual enough -- and it will be gradual enough because they’re going to continue to supply Europe with natural gas for some time to come at least at some level -- if it’s displacing coal, it’s all to the advantage, that’s today’s problem, the time to address it is now. Over time I think one hopes that the Russian economy becomes, this has been a hope for a long time, a more diversified, more successful, more open, transparent, so far so bad. But yes, I think one shouldn’t write off the possibility that the transition eventually will accommodate others especially as they experience the unattractive consequences of climate change.

Greg Dalton: It also hit the Russian wheat crop a few years ago very severely. We haven’t talked about China, the US-China deal was thought to be a game changer for the two biggest emitters, the biggest historic emitter, the biggest current emitter. So Christiana Figueres, how did the US-China deal change the dynamics for the Paris climate negotiation?

Christiana Figueres: You know, it was very important, it came just before the Lima meeting last year So it was very strategically timed.

And of course when you have the two big gorillas actually filing down their nails and saying, you know what, this is one area in which we can and we must collaborate. And it’s hard to find other areas in which China and the United States are willingly engaged in being interested in maximizing each other’s impact both separately from each other as well as collectively. That is a very, very important sign because it signaled two things: A, that the two highest emitters are taking this very seriously; B, that they’re all committed to doing something about it in their own countries: and C, that they’re actually interested in collaborating. And that message about collaborating across national territories is one that is really very seriously being considered now and is one of the most important how questions. How do we actually do that? Because the sum total of the individual efforts is not going to be enough.

Greg Dalton: Bill Reilly, the US-China climate deal also took away one of the biggest arguments in the United States which was, well, we don’t have to do anything because China is going to blow it all away anyway. So how did it affect the domestic dynamic?

Bill Reilly: The China move was very important. Former Secretary James Baker who himself delivered his first speech as Secretary of State about climate change and it was he who articulated the no regrets policy that characterized the early part of the George H.W. Bush administration. He has written that without China’s moving on this issue, it would create a very substantial competitive disadvantage the economy of the United States and therefore there’s no basis for our cutting back. That argument is being eroded very fast by moves that the Chinese are making. Now we can say that the Chinese have agreed to cap, you know, we’ve not gotten a homerun here, let’s face it, it’s going to take a long time. If they cap their emissions in 2030 there will be a lot of damage done in the meantime.

Having gone to China regularly with the China sustainable energy program that the Packard Foundation initiated some years ago, the energy foundation runs, I am impressed that the impacts are perceived now in China to a greater degree than they used to be. There used to be a pattern and I went to these annual meetings that if you used the word “climate change” or “global warming”, suddenly everything came to a halt and you got a spiel from the senior Chinese present who reminded you that the problem --

Greg Dalton: Sounds like Florida.

[Laughs]

Bill Reilly: Well, it’s true. We have places in this country where that is quite right. But that’s no longer true. They no longer tell you at great length that you created the problem, you have to solve it and it’s all your fault. That’s progress. It may not sound like much but it is. I think that they will be able to go farther, faster as they begin to exploit some of the technologies which they themselves have advanced. In manufacturing, for example, photovoltaics. I put photovoltaics in my house in 2006 and then again last year. They cost 50% less last year for a panel. That’s huge progress in a relatively short period of time and it reinforces the point that Christiana made that the solutions are now closer to hand than they ever were.

Greg Dalton: And let’s talk about the business case because climate is often talked about a problem, whoa, something doom and gloom but there’s a tremendous business opportunity and companies are seeing profit in this. So Bill Reilly, you’re involved with one of the largest hedge funds in the country, in the world, what’s the business case and the optimism for profits. Forget the righteousness and polar bears, but there is --

Bill Reilly: It’s not a hedge fund, it’s a private equity firm.

Greg Dalton: A private equity, okay.

Bill Reilly: But that is true. And one of the really significant developments that has occurred in the past few years is we have seen some utility grade solar, I mean, 120, 140, 180 megawatts of power, which is serious power, that is now being installed by companies for profit-related reasons.

They see that potential, the technology is there, the customers increasingly are asking for green power and that’s usually important to all of this. So you will see that transition begin to grow much faster than it has. We’ve already seen a place like Texas has huge amount of wind power, much more than any other state, which we started quite a number of years ago. And very successfully feeding into the grid which has been substantially increased in size to sustain bringing the power from the places where the people aren’t but where the sun is and the wind is, to where the people are. And I think that’s increasingly in our future and it’s a very promising sign from the point of view of business.

Greg Dalton: Christiana Figueras, how --

Christiana Figueres: You know, can I jump in here --

Greg Dalton: Sure.

Christiana Figueres: -- to pick up on Bill’s point. I think what we’re seeing is a very interesting push/pull evidence here where you’re seeing from increasing regulation, legislation, et cetera, you’re seeing a push and certainly from the increased awareness of impacts. But you’re also beginning to see as Bill was saying a pull from the customer base. There’s much more expectation now of responsibility, corporate responsibility. So you see the likes of Ikea, Google, Apple, you know, going 100% renewable, saying we want to produce our own renewable energy. Why? Because their customers want them to be more responsible. So there’s a very helpful, I think, you know, a virtuous cycle being created here, of push and pull, both from the regulation side, more regulations now than ever were, 800 already on the table across the world, but also the very important pull so that corporations are becoming much more aware of the fact that it is in their own interest. And fundamentally I think that is the really huge shift between where we were five years ago and now. That no matter what level you look at, if you look at countries, if you look at states, if you look at cities, if you look at corporations, they’re all beginning to understand as you were pointing out that it is in their self-interest to do this.

Yes, there is a huge threat. I’m not going to minimize the threat. But right next to that, there is a huge opportunity for countries, for cities, for companies. And that narrative has become or it’s starting now to take real hold so that it’s not just a narrative, there is actually a fundamental economic imperative that is being played out.

Greg Dalton: If you’re just joining us, our guests today at Climate One are Christiana Figueres, Executive Secretary of the UN climate negotiations and Billy Reilly, the senior adviser at TPG and former head of the U.S. EPA. I’m Greg Dalton.

We’ll be right back after this break.

[Climate One Minute]

Announcer: And now, here’s a Climate One Minute.

Todd Stern, the US Special Envoy for Climate Change, is also on the road to Paris. When he came to Climate One last year, he said he’s optimistic about what the summit can accomplish. But he also addressed criticisms that things aren’t happening fast enough by saying that the real work of climate change begins at home.

Todd Stern: The most important thing that can be done with respect to taking action on climate change needs to happen at the national level. The international agreement is important. I mean, that's what I spend my time doing. I know I wouldn't do it if I didn’t think it was important. But action, real action gets driven at the national level. The international agreement stitches countries together and gives countries confidence that others are also acting and so forth. So it's got a real role. So yes, I think progress is being made. And I don’t think progress -- I agree, progress is not being made quickly enough.

Announcer: That was Ambassador Todd Stern, US Special Envoy for Climate Change, speaking at Climate One in 2014. Now, back to Greg Dalton and his guests at The Commonwealth Club.

[End Climate One Minute]

Greg Dalton: Christiana Figueres, the heads of major European oil companies wrote you a letter recently, what did they say?

Christiana Figueres: They said they want to be part of the solution. They said they want a price on carbon.

Greg Dalton: Did you fall off your chair when you read this?

Christiana Figueres: No.

Greg Dalton: Okay.

Christiana Figueres: No I didn’t fall off my chair because it’s a very natural evolution of a conversation that we’ve been having with them and it’s a natural evolution of this process. I go back, right? This is one step in that push/pull where frankly oil and gas companies have to be a part of the solution. If they want to have business continuity, it’s a very clear choice, do you want to continue to be a company or do you not? If you want to have business continuity, you have to get with the program and you have to understand that we are going into a low carbon economy. Do you want to contribute to that? Fantastic. Because these oil and gas companies, they have very, very deep pockets and they have an amazing engineering capacity that is unequaled in any other sector. Once they get those two together and put them at the service of their clients today and tomorrow, this is an unstoppable force.

Greg Dalton: U. S. companies were notably absent, Chevron, Exxon, why weren’t they there? Do you know?

Christiana Figueres: They were invited. They’re not ready. They’re not ready for, you know, reasons that are probably better known by people who carry a U.S. passport than me.

[Laughs]

But I don’t take that no as a permanent no. I take that as a “not yet.” I take that as: I need more conversation, I need more evidence, I need, you know, even more compelling economic imperative evidence to be put in front of me. So I do not close my door to them. My door has always been open, I am very proud of the fact that I have been talking to all of these companies and I shall continue to that, because they have to be part of the solution. We’re not going to solve this without them.

Greg Dalton: Bill Reilly, eight years or so ago there was a group of energy companies including General Motors and others tried to create a new center in American politics around climate change. European oil companies were part of that, U.S. oil companies were not with the exception of the one you are on the board of, ConocoPhillips. Are U.S. oil companies falling behind?

Bill Reilly: You know, the surprising thing to many of these CEOs is that we have still not enacted legislation to regulate carbon. They expected it would come much sooner.

Greg Dalton: They’ve been working really hard to stop it, slow it down.

Bill Reilly: Some of them are working very hard to stop it but they’re surprised they were successful.

[Laughs]

The fact is they have shadow pricing. So from an economic self-interest point of view, they’re fully prepared. But only do they have shadow pricing which is actually a sign --

Christiana Figueres: At $60 to $80 a ton.

Bill Reilly: Seventy-five dollars is a ton, that’s right, for Shell that’s right. I don’t know what it is for Exxon Mobil. Exxon Mobil publicly has long claimed an interest in seeing a carbon tax imposed.

But not only have they moved on that front, they have obviously pioneered fracking which has made possible the President’s program that has reduced by I think it’s something like 11%, the emissions, heading toward the goal of 17 set in Copenhagen, but they have moved very heavily in the gas. And with that presumably is the transitional fuel which they look forward to continuing to sell. I very much support the concept that they have sophisticated engineering, that’s quite sophisticated stuff, and they’re energy companies and so characterized most of them that way. Not necessarily oil companies at the moment. So I don’t think that they will be inconvenienced that seriously when finally we get a carbon tax. I think they’re already seeing for example the consequence of the President’s agreement with the auto industry that will have the effect of reducing 54.5 miles per gallon automobile fuel efficiency, reducing by over two million barrels a day of imports of oil in the United States or need for oil. That’s a very significant move. And you put that together with the President’s carbon rule which affects 40% of the sources, the electric-generating companies, the trend is pretty clear that we’re making progress on this problem. We hear so much about how congress has not addressed it, and it hasn’t, but that has not stopped the culture, the economy, cities and finally a lot of these companies for making the progress that we need.

Greg Dalton: Let’s talk about Pope Francis. He recently entered the fray on climate. He has done some remarkable things. He said recently that man has slapped nature in the face. He came out very strongly in support of climate on his encyclical. Christiana Figueres, how does this moral voice affect the prospect for a climate deal?

Christiana Figueres: I think it’s a very important contribution to the conversation. The moral imperative on climate change has been made for many years.

But the clarity and the clarion call from the Pope, who is motivated truly from his sense of justice, is very moving. And it really, I think, you know, it sort of shakes the ground that you stand on. You cannot be untouched by a call like that. We all get up in the morning and look at ourselves in the mirror, you know, no matter what our job is, we all look at ourselves in the mirror and the first question we should ask ourselves is, what do I really want to do with my life? What do I really want to be my legacy, what kind of a planet am I turning over to my kids, my grandkids? We all do that. It doesn’t matter what our profession is. And I think that is what he’s calling for, you know, he’s saying, okay, ask yourself that question and answer. Because there is a compelling economic imperative that has been made by many other people. But side by side, the question is this not something that we can all agree to.

Greg Dalton: Bill Reilly, you had an audience with the Pope a couple of weeks ago, tell us about that and how this changes the dynamic in the U.S.? 30% of Congress is Catholic.

Bill Reilly: I think it changes it very significantly. The surprise about the Pope’s statement, one expected that he would set out to the theological underpinnings for stewardship, creation care and the like, which previous popes have done eloquently. I think the surprise is that his message is on several planes. It’s on the plane certainly of theology and morality. It also gets very close to the realm of policy and action. It calls out people who are not accepting climate change and suggests that indifference or excessive belief in a technical solution or just opposition to science is unacceptable on a moral plane.

That’s very consequential, I think. Finally, and one expected this would be true, he has a very heartfelt and affecting statement of concern on the part of poor, and the disproportionate effects that they will suffer. I have been chairing a climate smart food security component for the global development council the President established. And if you look at the situation of a farmer in Southern Africa who has four kids and maybe one hectare of land, there’s so many prospects that she can improve her plight, her husband maybe works in a bank, it’s very rare that both members of a family will work on a farm, and just by increasing grain output from one to two tons per hectare. Which on the European or U.S. experience is not that much and there are many ways to get there with precision farming and cell phones and all the rest. However, the one thing that she cannot manage or anticipate or deal with, is a very severe shortage of water, of rain. And if that should happen, it’s not clear where the solution will be.

That’s the kind of thing that climate change could present to the poor. And multiply her by millions in, not just in Africa but in Asia and particularly in South America as well. He shows a great deal of compassion for that and in the statement connects those concerns with consumption. Not an altogether easy message to accept in the consumer societies that those of us in developed countries live in, but a very important and direct, I think, encouragement to reflect personally on the consequences of our choices.

I have that impression that there is a sense that on the part of the majority of our country which is supposed to care about climate change according to all of the polls, well, yes but it’s not clear what we can do about it. I think he makes pretty clear that it is us, up to us to do something about it. And it gets very close to what those things are.

Greg Dalton: And how about the 2016 election cycle? We’re in the midst of a presidential election yet you noted earlier that President Bush signed the convention during a presidential election, we’re in this now. How does the Pope or how’s the politics of climate change going to play in 2016, Bill Reilly?

Bill Reilly: Well, you know, I so often hear from members of Congress even those who are very committed to doing something about climate but they do not hear it on the hustings. When they go home for Christmas or Easter vacation it’s not raised by constituents. One would hope that this communication if it gets into circulation and I understand that they’re going to send statements to every parish in the world, I’m not aware that’s ever been done in response to a papal statement. But that could cause perhaps a ground swell of questioning and concern and the voters begin to raise the issue. If they do raise it, I have every confidence that the system we have will respond to it. Some of you may remember that it was in 1989 we had an unprecedented hot summer of ozone alerts and environmental droughts and environmental issues and all of a sudden we have Ronald Reagan’s vice president promising to become the environmental president. That happened in one season and ozone depletion, upper atmospheric ozone depletion and discoveries about that, played a part in it. But that can happen again and I think that the encyclical is one more very significant impulse to help create and happen.

Greg Dalton: If you’re just joining us we’re talking about climate change at Climate One. Our guests are Bill Reilly, former head of the U.S. EPA and a senior adviser at TPG Capital, and Christiana Figueres, Executive Secretary of the United Nations climate negotiations. I’m Greg Dalton. I’d like to go to our lightning round where we ask you just a brief single yes or no question.

Bill Reilly: This is trouble.

Christiana Figueres: Lightning round or lightning rod?

[Laughs]

Greg Dalton: Well, it depends yes.

[Laughs]

Christiana Figueres: What did you say?

Greg Dalton: Lightning round.

Christiana Figueres: Oh, we have a lightning round.

[Laughs]

Bill Reilly: Yeah, I think so.

Greg Dalton: Canada is becoming an economy dominated by petroleum, a petrostate. Yes or no?

Bill Reilly: Yes.

Greg Dalton: Christiana Figueres, people will not change their lifestyle to save polar bears.

Christiana Figueres: True. But that’s not why they should change.

Greg Dalton: Okay. Another for Christiana Figueres, have you ever wanted to strangle a diplomat at the UN for talking a lot and saying nothing.

[Laughs]

Christiana Figueres: Let me say I wanted to turn the microphone off.

Greg Dalton: That’s much more diplomatic.

Bill Reilly: Careful, Christie, he’s going to ask for names.

[Laughs]

Greg Dalton: Bill Reilly, the symbolic value of the Keystone XL Pipeline is greater than the carbon value.

Bill Reilly: True.

Greg Dalton: Bill Reilly, the U.S. invasion and occupation of Iraq was significantly about oil.

Bill Reilly: False.

Greg Dalton: This is for both of you. What is your carbon vice?

Christiana Figueres: Carbon vice? Airline travel.

Greg Dalton: Common one, yeah.

Bill Reilly: Yes. Likewise.

Greg Dalton: Airline travel. Okay. Last one for Bill Reilly. Are more U.S. politicians in the climate closet or the gay closet?

[Laughs]

Bill Reilly: Well, I’ve been trying to think what personal knowledge I have of either.

[Laughs]

You know, the question could be a serious one. I have had someone say, well, the way you phrase it, I have had a congressman say at least 100 Republican members fully understand and get the climate issue. But were they to have embraced, this is at the time of Waxman-Markey, were they too have embraced carbon regulation, they would have been well-advised not to stand for re-election in their primary, that it’s a constituency issue. And it’s very important for those of us who try to drive change on this to recognize that and to recognize that we’ve really got to change the culture before changing the politics successfully. That’s got to happen and I’m talking about some very good members who are quite sophisticated and would like to embrace this what they see as the course of history here but need protection if they do.

Christiana Figueres: But that where it’s taking this issue to the kitchen table as you were talking about, you know, with the Pope and then working down to the parishes, that’s where that can be really helpful. Because it’s got to be a kitchen table conversation. Unfortunately in my home it was a kitchen, dining room, bathroom, you know, living room conversation. But, you know, it’s got to be at least a kitchen table conversation so the people begin to understand the impact of what we’re doing.

Greg Dalton: So speaking of kitchen tables, someone is sitting around a kitchen table in America, why should they care about the Paris climate deal? What’s at stake for them, Bill Reilly? How is it going to affect someone’s lawn, someone’s SUV, someone’s lifestyle?

President Bush famously said in Rio in 1992, the American lifestyle is not up for negotiation, is that still the case?

Bill Reilly: I think that an agreement in Paris is going to create an international impression of the direction that policy, cultures, economies will begin to go in. I think there will be reverberations for behavior on the part of city councils, on the part of governors, mayors, private associations, NGOs. I think you will see an evolution towards decision-making that is much more sensitive to the climate impacts, to the emissions consequences of choices in manufacturing, in standards for equipment, in industry and the behavior of industry. A lot of people are waiting to see what happened, there was huge disappointment, I was in the philanthropic community at the time when Copenhagen disappointed us and when the failure of Waxman-Markey was further disappointing. We very much need a success in Paris. I would say that the bar has been set low enough that we will get one.

Christiana Figueres: I’m not sure that I will agree that the bar is low.

[Laughs]

Bill Reilly: Well, we’ll see how that comes out. I think very important progress has already been made in the United States and China as we’re discussing Europe. And there’s every reason to be positive about the direction things will go. And I think it’s actually correct to design it in such that everybody can come out a winner. I think it’s time for that on this issue.

Greg Dalton: Christiana Figueres, you travel the world, why do people sitting at kitchen tables outside of America, what’s at stake with the Paris negotiations? How do you make it a kitchen table conversation as you say?

Christiana Figueres: You know the astonishing thing is that there is so much awareness outside of the United States than there is in the United States.

And whether people call it climate change or not, I talk, you know, to people who are out there and are aware of the climate impacts directly on their life. I talk to people who are already witnessing migration, not of animals, of trees. Trees are migrating up the mountain because they no longer have the temperature and the rainfall that they need. So they need to move. And that, you know, you would say, well, that’s a relatively benign impact. But I also go to small island development states where the little villages have been now raised up on stilts because the entire area of the village is a constant salty swamp because the water level has gotten there. And you see all kinds of animals, crabs and other animals that normally would only be on the beach already completely invaded the village, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera. So it’s about experiential pain, right? It’s about so many people are actually living this on a daily basis.

Greg Dalton: And climate impacts disproportionately fall on women, tell us how.

Christiana Figueres: Disproportionately fall on women and particularly in developing countries because women are disproportionately responsible for food, water and energy. So they sit at the nexus of that. Women in developing countries -- in Africa 75% to 80% of food is brought in by women. Women are usually, if not always, responsible for cooking. For cooking they need the water, they need the food and they need to figure out how is this going to get cooked.

So you have women walking two, three, four hours out to the forest to get wood, to come and cook food. You have them walking the same number of hours to get water to come and cook their basic food. On the road to get all of these basics horrendous things happen to women. And then of course they are responsible for that meal at the end of the day come what may. So they are truly at that nexus between energy, water and food and really responsible for that to ensure that their families survive. They are getting hit more than anybody else. They don’t call it climate change but they are getting hit more than anyone else. That is why there are so many initiatives to actually focus very clearly on how women can begin to adapt and how they can begin to provide more water and food security to their families by introducing better crops, by introducing in the case of Bangladesh one of my favorite examples, a cooperative of women, who have now substituted chickens for ducks because they keep on getting more and more floods. So out with the chickens, in with the ducks, very smart, right?

And there is, you know, one of my absolutely where my heart really lies, an amazing initiative that is now coordinating many, many NGOs around the world that is looking at 50% of women, I have to tell you, you have to put this data point in your brain, 50% of women not in developing countries, 50% of women in the world are still cooking on open fires. That means three stones, three pieces of wood, pot. Fumes, you know, killing their own lungs and those of the children. That has got to stop. That to me is morally absolutely unacceptable. And the fantastic thing is you can use the different tools that we’re developing under the climate convention to actually allow these women, 50% of women in the world, to cook in a more responsible way for the planet but more importantly for themselves and for their health.

So how you bring together national family concerns with the global solutions is actually the way to go particularly when it comes to women.

Greg Dalton: Those solar cook stoves are pretty cool things. We’re going to go to audience questions, but first I want to want to mention, you mentioned island states, Christiania Figueras, Mohamed Nasheed is the former president of the Maldives who’s been incarcerated,who’s really a climate prisoner, what can you tell us about his case if you know anything.

Christiana Figueres: It is of huge concern. He was while he was president he was really one of the very eloquent and very compelling speaker for the reality of small island states. And the fact that he is now in the condition that he is, that has nothing to do with climate. It has to do with internal politics. That’s very lamentable.

Greg Dalton: Let’s go to audience questions. Welcome to Climate One.

Female Participant: Thank you. Thank you all for being here. My question to both of you which will not be solved at the coming negotiation in Paris but -- is 2 degrees Celsius enough, that is almost 3 and a half degrees Celsius -- excuse me, Fahrenheit, is that going to be enough when we do get to making sure we stay under the 2 degrees Celsius.

Greg Dalton: Christiana Figueres.

Christiana Figueres: A very important question, Holly, and one that is actually very much on the table right now. In fact, the last two weeks of negotiations in Bonn had many countries rallying around the 1.5 degree temperature because they feel that although there was a political compromise in Copenhagen to set under 2 and then have 1.5 only be a reference, they feel that that under 2 does not guarantee their survival and they want to raise the political visibility or actually put into political parity 1.5 to under 2.

So it is very much of a concern because while in Copenhagen there was that agreement and that compromise, science now has advanced to the point where it is becoming more and more alarming. So to be followed that conversation but very difficult.

Bill Reilly: I would only add to that, Holly, that 2% was a political number --

Christiana Figueres: 2 degrees.

Bill Reilly: 2 degrees was a political number and business as usual will over reach significantly 2 degrees. I think most people know that. And the sense has been on the part of a lot of people at least that, well, let’s stay with 2, it was a consensus number at the time even though it isn’t entirely clear how we got there. But we certainly do want to get at least to there and over time as Christiana suggests we will find that we have to go further. But for the moment, I am not sure that I would agree that dropping 2 degrees or making it even a harder goal to achieve is a good idea until we can at least see how we might get to 2.

Greg Dalton: Let’s have our next question for Bill Reilly and Christiana Figueres.

Female Participant: Good afternoon. Thank you for being here today. My name is Mary Selkirk. I’m with the Citizen’s Climate Lobby. And as Mr. Reilly has attested today and many economists, investors, oil companies, civil society organizations, the World Bank, the IMF, have attested that decarbonizing the economy the most effective way to do that and mitigating climate change is through pricing carbon.

And so my question is this for Ms. Figueres and Mr. Reilly mentioned earlier that in your remarks that oil and gas industry will not be inconvenienced by a carbon tax. So my question for Ms. Figueres is in the run up to the Paris talks, what do you think it will take, because the current negotiating language is quite undetailed and vague with respect to committing to carbon pricing mechanisms as a way to mitigate climate change. So your comments on how the negotiators will make that happen in the next six months.

Christiana Figueres: Mechanism is the operative word in your question because the Paris agreement is actually taking a very, very high level view because the purpose of it is to be on the shelves for 20, 30 years. It does not want to be something that is short-lived. So understandably it has to take a very high view and it is actually more addressing the what than the how. The how is carbon pricing and we know that we can get carbon pricing through either tax or ATS or many other different economic instruments. So I don’t think that the agreement itself will get into those hows. I do know that there are quite a few countries, in fact 77 governments and a thousand corporations that have signed up to this alliance for pricing carbon and that they are talking about allying themselves, a coalition of the willing if you will, or a coalition of the interested, to make a political declaration perhaps coinciding with Paris who are calling for carbon price. But I don’t think that we’re in a scenario in which we would have a carbon price globally come down but rather the respect of 40 jurisdictions around the world now that have different carbon prices that are coming up and then eventually will lead to price discovery that standardizes across.

Greg Dalton: Let’s have our next question for Christiana Figueres and Bill Reilly at Climate One.

Male Participant: My name is Gary Horvitz. I’m with Citizen’s Climate Lobby. What is the message that you would like to give to Republicans in the closet to invite them out or to ask them to support the process that is going on in Paris?

Greg Dalton: Bill Reilly?

Bill Reilly: In my own sense is that I would press them to begin the conversation with their constituents. They’ve got religious constituents that are particularly important to them, they have evangelicals in any number of congressional districts, red districts. I would start that conversation and use the Pope’s encyclical as a basis for it. Those who are sympathetic to the direction needn’t say they’re changing their position but they’re certainly considering the questions that have been raised by responsible people. I think that’s something that they could do and without necessarily risking their political futures, that’s what - you’ve got to keep that somewhat in mind despite the urgency we may feel about these things. That’s the way the real world works.

I would start there and try to make it respectable to discuss these alternatives. I know that a carbon tax is anathema on the part of any number of Republican members, well, not just Republican members, others as well. In the context of tax reform a neutral, revenue neutral carbon tax could solve a lot of problems including displacing the reduction and the corporate tax which the President and the congressional leadership has wanted to do for some time. I think there are things you can say that would have resonance with that community, respecting where they’re coming from and some of the constraints on them and gradually moving them to a more positive position that so many of them do I think privately recognize has got them at the moment not there and on the wrong side of history.

Christiana Figueres: Can I say one sentence to that. I would add to that, the other side of that which is totally complementary, which is this is fundamentally a race of technologies and other countries are already in the lead. The United States needs to simply make a decision. Does it want to be a market maker or does it want to be a market taker because right now it’s a taker.

Greg Dalton: Welcome to Climate One.

Male Participant: Well, all the countries in the world obviously need to come together, it’s a global problem, global solution. But really we’re still in a world where companies, I mean, sorry, countries are competing both militarily and economically to be number one even in the green race. In Copenhagen and all the COPs [Conferences of the Parties], there’s this process of consensus and when there’s a severe economic and political inequality, can consensus work? Are there any ways in Paris that will help deal with the complexities of negotiating the consensus procedure?

Greg Dalton: Christiana Figueres.

Christiana Figueres: It’s very difficult but it’s unavoidable because I hear people tell me, well, you know, 20 countries in the world are responsible for 80% of greenhouse gases so wouldn’t it just be easier to just get 20 countries in the world to gather around one table and solve the problem. Yes, except what do you do with Vanuatu? Vanuatu was hit by one typhoon, it destroyed 70% of its infrastructure. Are you willing to stand there and tell Vanuatu you can’t have a voice at the table? No. Everybody has to be there because there is not one country that is not impacted in one way or the other. So sorry folks, we have to do this by consensus. There’s no other way.

Greg Dalton: Last question.

Male Participant: Robert Archer, retired economist. The World Bank and Transparency International Industries show a lot of low and moderate and middle income countries suffer from weak institutions and serious corruption. Will the UN, World Bank and IMF provide support to the countries that want to pursue the simpler and more transparent carbon tax policy?

Christiana Figueres: Well, the UN, the World Bank -- the UN with all its system and the World Bank and the IMF is providing support to countries to implement the measures that they see fit. It is not up to the UN or in fact even to the World Bank to impose a particular policy or a particular measure so the exercise right now is for all these countries to go home and do their homework and figure out where do they want to be, what is their contribution both on emission reduction as well as on adaptation. What are the policies and measures that they think are going to be most effective, and then get the support to do that.

Greg Dalton: Bill Reilly.

Bill Reilly: I think that’s a very important issue. I think that we do not want to squander the support for helping some of the developing countries by allowing the funds to become lost or corruption to distract them. And I think it’s important to recognize we have new techniques of foreign assistance, pay for performance, cash on delivery pioneered by Norway when it offered a billion dollars to Brazil to protect against further deforestation of the Amazon, but did not transfer the funds until the project had been completed, until the government had actually succeeded in significantly reducing the deforestation.

There are any number of models of other kinds of assistance that can be given that way. And I think it’s very important that in the transfer of funds whatever the portion is that is finally made available to developing countries, there be those kinds of controls and incentives in monitoring in transparency. Because we’re going to want the countries who are supporting these programs, these funds to believe in what they’re doing and to see that it’s genuinely making a difference.

Greg Dalton: Last question for Bill Reilly and Christiana Figueres. We’ve heard a lot about it’s urgent, people have to do things, what can an average person do in their daily life? This all seems so big, can we bring it home to that kitchen table? What do you do in personal life, what can average person do to make a difference in something that seems so big? Christiana Figueres.

Christiana Figueres: You know, right now because the grid system because the energy system is so carbon intense we do have to make personal choices. Eventually the energy system will actually take carbon out and it will be the pressure on behavior is going to be relieved. But right now it truly is important that we make personal choices. So how do you transport yourself? It does make a difference if you have, you know, an SUV or if you drive a little Prius if you drive.

It does make a difference whether you buy products that come from halfway around the world or whether you buy products that are locally produced. All of these things do make a difference. It does make a difference if you turn your darn computer off at night because, you know, it takes two more seconds to turn it on the morning. I mean, honestly, it’s small things that we can really do. But if all of us do it, it makes a difference and it’s about getting it into our brain.

Greg Dalton: Bill Reilly.

Bill Reilly: I think it’s important for people to engage in some personal reflection about their choices, about the things they buy and about whether they need what they buy and about the plight of the poor and the people who are going to suffer most, whether in some of our communities or around the world. And secondly, to engage the public policy process at least to the point of creating expectations for their representatives that this problem be taken seriously. We cannot solve the problem alone in our lives or our families, but we do expect that there will be a socially agreed solution to this, that we’ll all change the compact and that this problem will matter much more than it has mattered before and that there are moral reasons why it should.

Greg Dalton: We have to end it there. We’ve been listening to Bill Reilly, senior adviser at TPG Capital and former head of the U.S. EPA and Christiana Figueres, chief of the UN climate negotiations. I’m Greg Dalton. You can listen to a podcast of this and other Climate One podcasts on our website, climateone.org. I’d like to thank our audience here in San Francisco and online and on the air. Thank you all for coming today.

Christiana Figueres: Thank you.

Bill Reilly: Thank you.

[Applause]

[END]