Cigarettes and Tailpipes

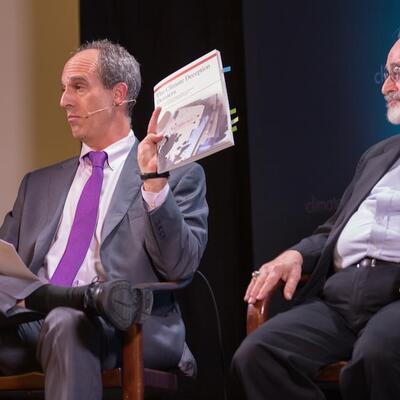

Guests

Lowell Bergman

Stanton Glantz

Kenneth Kimmell

William K. Reilly

Summary

Cigarette makers downplayed the dangers of smoking for decades with distracting science. How close is the link between tobacco denial and climate denial?

Lowell Bergman, Investigative Journalist

Stanton Glantz, Director, Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education, UCSF

Kenneth Kimmell, President, Union of Concerned Scientists

William K. Reilly, Senior Advisor, TPG

This program was recorded in front of a live audience at the Commonwealth Club of California on February 18, 2016.

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: I'm Greg Dalton. And today on Climate One we will compare the stories of the tobacco and oil industries. In the 1990s, tobacco company documents leaked to the news media proved for the first time that cigarette makers knew their products are addictive and cause cancer. The documents also demonstrated that the companies waged a concerted campaign to cover up and distort the science of smoking. When the American public realized tobacco companies lied to them, the companies faced such political and legal opposition they agreed to pay $200 billion in penalties over 25 years. The companies also agreed to limitations on their advertising, sponsorship and lobbying activities.

A similar narrative is unfolding in the oil industry today. The Los Angeles Times and Inside Climate News reported recently that scientists at Exxon Mobil studied global warming as far back as the 1970s. One company scientist told an industry conference in 1991 that melting tundra and sea ice would reduce the cost of exploring for oil in the seas of Alaska. At the same time that it was planning a strategy to take advantage of a warmer world, the company waged a PR campaign denying that burning fossil fuels was heating the planet. Over the next hour we will revisit the tobacco wars of the 1990s and explore how they are similar or not to the battles today over fossil fuels. Along the way, we’ll include questions from our live audience at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco.

We have four guests on the program today, who played pivotal roles in both stories. Lowell Bergman is a professor at the UC Berkeley School of journalism. He earned a Pulitzer Prize and many other awards as an investigative journalist working for CBS News, The New York Times and Frontline. As a producer for 60 minutes he investigated the tobacco industry. Stanton Glantz is Director of the Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education at the University of California San Francisco. Often called the Ralph Nader of the anti-smoking movement is an advocate for non-smokers’ rights and public health policies to reduce smoking. He’s the author of four books, including Tobacco War: Inside the California Battles. Ken Kimmell is the president of the Union of Concerned Scientists; he’s an attorney with extensive experience in private practice and public service. He worked in the executive office of Massachusetts Governor Patrick Deval and also headed the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection. The Union of Concerned Scientists recently published The Climate Deception Dossiers on the PR and lobbying activities of fossil fuel companies. Bill Reilly was administrator of the U.S. EPA under the first President Bush. He held that position during the Exxon Valdez oil spill. He later joined the board of the oil company ConocoPhillips after the BP oil debacle in the Gulf of Mexico, President Obama appointed him as a Republican co-chair of the national commission that investigated the deadly disaster. He’s currently a senior advisor to TPG Capital and a member of our own Climate One advisory council. Please welcome them to Climate One.

[Applause]

Stan Glantz, let's begin with you. Take us back to say the 80s when people started to be more concerned about the health impacts of tobacco and the social license and the attitude towards smoking started to change from when the era of Mad Man that every – lots of people smoked.

Stanton Glantz: Right. Well, the public concern over the issues of tobacco really started to appear way back in the 1950s when Reader's Digest published an article called Cancer by the Carton. And there was tremendous public concern states were talking about banning cigarette advertising. There were demands to have Congress regulate the tobacco industry. And the tobacco companies responded to the scientific evidence that smoking was causing cancer by mounting a public relations campaign. And they realized that they couldn't really contest the evidence linking cancer and smoking so they came up with the idea of creating doubt. Now there’s a very famous document in the tobacco industry, a document saying doubt is our product. Because all they had to do was get people confused about it and by claiming that the issue wasn't proven that provided cover for politicians to leave them alone and it helps smokers rationalize their continued smoking. And that was really the beginning of a massive conspiracy that actually continues to this day.

When President Clinton was president, the Department of Justice actually brought a racketeering lawsuit against the tobacco industry for fraud based in large part on the deception documented in the tobacco documents. Because if you go way back to the 50s at the same time they were saying to the public, you know, we don't know what's, whether smoking causes cancer or not. Their own scientists internally were saying smoking causes cancer. Now they were careful to avoid the word cancer they use the word zephyr. But it was very, very similar to what you described in the introduction to where the scientists inside the oil industry were saying “Well this is going on and we need use it for our business planning.” while at a time that the oil industry was contesting the evidence publicly.

And you find over and over and over again in the tobacco documents where the research the companies were doing inside the companies was very high-quality research, often 30 or 40 years ahead of what the mainstream science was saying. They understood that smoking caused cancer in the 50s, they understood that nicotine was addictive in the 60s. It wasn't until 1988 that the Surgeon General finally said nicotine was an addictive drug. So when I look at these two areas I see tremendous parallels in part because a lot of the same people and companies that the tobacco companies hired to create doubt and confusion about the dangers of smoking subsequently went to work for the petrochemical companies to do the same thing.

Greg Dalton: And we’ll get into that. Lowell Bergman, you came into this in the early 90s. So tell us how you got to meet Jeffrey Wigand and then we’re gonna play a little clip of that movie.

Lowell Bergman: Some documents landed on my doorstep in Berkeley where I lived. And I was working for 60 Minutes, I’d been there that point for about a decade. And they were about a tobacco, Philip Morris and they were headlined Project Hamlet: to burn or not to burn. And it was about fires caused by cigarettes which had killed and that year killed 7,000 people and 300 children in the United States. And a project that they had to develop a Marlboro Light that tasted like acted like a regular Marlboro Light. And it was extensive experimentation and taste groups and went on for years and finally it appeared that the attorneys came in and stamped it all attorney-client privilege and took all the research back out of the research part of Philip Morris.

My problem at the time was that CBS where I worked had just been sued in 1993 by the Brown & Williamson tobacco company for a commentary by a local personality on its Chicago station and lost the largest libel judgment in the history of the United States because he had equated the tobacco industry with the Nazis and with Goebbels.

And so to go forward I knew and they were very litigious, so they spent $600 million a year in those days on lawyers. And so we knew you could get sued if you did something about tobacco industry; not to mention that the owner and CEO of CBS that time Larry Tisch owned Lorillard Tobacco. So to put those all together we went in search of some independent expert who could read the document so we could show that those documents actually independently of our judgment were substantively true and this is what they were actually doing. And it was at that moment that a source of mine came forward and had called me and said, “I've talked to a guy who was on the tobacco fire safe congressional commission who was from Brown & Williamson Tobacco and he just got fired and he says he’ll talk to you.” And that was the beginning of the dance; it took about six months before he agreed to meet with me.

Greg Dalton: And Jeffrey Wigand becomes a key character. He’s a whistleblower, a rare thing in Fortune 500 companies. And then so you started developing some stories with Jeffrey Wigand –

Lowell Bergman: Well I should say I had the experience of putting CIA agents on camera, arms dealers, Mafioso, but never a fiduciary officer of a Fortune 500 company. That’s the rarest character to see come out in public and talk. And I must say in the Los Angeles Time series that were done with Columbia University. What was interesting to me is when I read it was the number of Exxon scientists and others were openly talking. So there's a big change from what was going on in tobacco.

Greg Dalton: So let's watch this is a clip we have of Jeffrey Wigand who’s, it’s a key moment in this the film The Insider, in which Al Pacino plays Lowell Bergman and Christopher Plummer plays Mike Wallace and Russell Crowe plays Jeffrey Wigand, who's the whistleblower. And this is a scene we’ll show from that film.

[Video Playback]

I believe that nicotine is not addictive.

I believe Mr. Santos purgered himself because I watched those testimonies very carefully.

All of us did. There was this whole line of people, whole line of CEOs up there all swearing.

Part of the reason that I'm here is that I felt that their representation clearly misstated what is common language within the company. We are in the nicotine delivery business. There is extensive use of this technology known as ammonia chemistry. It allows for the nicotine to be more rapidly absorbed in the lung and therefore affect the brain and central nervous system.

And that's what cigarettes are for.

A delivery device for nicotine.

[END VIDEO PLAYBACK]

Greg Dalton: So that’s from The Insider with Russell Crowe and Al Pacino and Christopher Plummer. So Lowell Bergman, tell us the significance of that revelation, having that character go on camera. It’s different to have documents than to have an actual whistleblower and a person that'll say that.

Lowell Bergman: Well the documents are documents and as a famous lawyer once said, the documents don't lie and the documents don't go away. But the problem was, what do they really believe inside the tobacco industry, what do they really talk about when they get together. And so he was unique. There had never been anybody in the tobacco industry as far as I had researched other than John DeLorean from General Motors any former executive who is at a vice presidential level of a major corporation to step forward and actually talk about what they say to each other when something is obviously true. So that was his significance. I have to say though that tobacco as it says we said in the 60 Minutes segment when it finally ran in general is a product that if you use it will kill you if you use it as directed.

And fossil fuels don't necessarily kill you, you know in and of themselves, so we have – there’s a different scale different kind of thing going on here.

Greg Dalton: A key point there Ken Kimmell, everyone here listening to this in this room, listening to this used fossil fuels today. It makes our life, you know, enables modern life in a way that’s very different than tobacco, yet there are some similarities between the tobacco episode and tactics and players. So tell us about the similarities and the doubt.

Kenneth Kimmell: Sure. There are some differences, but there are some similarities. And one thing to point out is some of the documents that you gentlemen are referring to emerged after a lot of litigation and discovery processes. Those have not yet happened for the fossil fuel industry. But despite that what we have already discovered is I would say fairly damning. And if I could, let me peel back the onion a little bit so people can see what actually happened and judge for themselves how closely similar it is to what happened with tobacco. So last summer as Greg pointed out we put out a publication, UCS called the Climate Deception Dossiers. And just to give you a feel for some of the things that are in there, the story starts a long time ago but I'll start it in 1995 when the petroleum companies formed a global climate coalition to provide kind of a unified response to the discussions that were ongoing about climate change and what to do about it. And the first thing they did actually was to hire their own scientific team to give them advice on climate change. And that team was headed by the chief scientist of Mobil and the memo that was provided to the global climate coalition said as follows: “The scientific basis for the greenhouse effect and the potential impact of human emissions of greenhouse gases such as CO2 on climate is well-established and cannot be denied.”

Fast-forward three years; the Kyoto Protocol has now been negotiated and pending before the United States Senate is to ratify the treaty. And the American Petroleum Institute, funded by the same people who were in this global climate coalition created a global science communication team. Some of the people who were on that team were people who worked for the tobacco industry and here's what they said their goal was. “Victory will be achieved when average citizens “understand” – and understand is in quotes – uncertainties and climate science recognition of uncertainties becomes part of the conventional wisdom.” They go on to say and this sounds a little bit like Spectre from the James Bond movie. “Unless climate change becomes a nonissue, meaning that the Kyoto proposals are defeated and there are no further initiatives to thwart the threat of climate change, there may be no moment when we can declare victory for our efforts.”

And in that memo they detail a public relations strategy which really has two prongs. One is a great deal of public announcements and Op-Eds and advertisements trying to claim that there is doubt about climate science. And if you go back in time you'll see a lot of those types of publications in the late 90s and the 2000's. Ironically, when they say publicly that climate science is uncertain, it turns out that they knew how to read the advice of their chief scientists. They were actually following their scientist’s advice about climate change when it came to their own investment decisions about things like offshore oil platforms and pipelines that might freeze in the tundra and warm-up due to climate change. So they perfectly understood this and yet they denied it publicly and they launched a campaign to cultivate and fund contrarian scientists.

One of those scientists is a guy name Willie Soon whose theory is that solar variability is what causes climate change. Interestingly, that 1995 memo itself said that that theory was not valid and couldn't account for climate change. But Mr. Soon got funded to the tune of $1.2 million over a ten-year period, and he had a very interesting funding arrangement. He worked for the Smithsonian and the deal for his funding was twofold. The companies that funded him like Exxon Mobil insisted they get the chance to see his publications before they were made public and they insisted that the Smithsonian agree not to disclose that Exxon Mobil was actually funding his work. So there you have it, you have certain knowledge of the risks of climate change. You have the people themselves saying their goal was to create a campaign to sow doubt and the execution of that.

And I guess the point I want to make is that is just the tip of the iceberg. We now have an investigation by the New York Attorney General and the California Attorney General. My prediction is a lot more is gonna come out and this conversation will heat up dramatically over time.

Greg Dalton: Bill Reilly, you’ve been on both sides of this as the country's top environmental officer and also a fiduciary officer in an oil company. How do you respond to kind of some of these stories that you’ve just heard?

Bill Reilly: Well one of the priorities that we set at the beginning of my term at EPA was to pay attention to the air problem. That hadn't been addressed in any way at all despite the expenditure of billions of dollars to try to regulate automobiles and factories, utilities, and so forth. And that is indoor air. And the science advisory board to EPA was very concerned about that being a source of mortality, morbidity that were really largely neglected.

The most significant implicated problem was smoking. And so I declared this my last regulatory call decision, I declared side stream smoke, a class A carcinogen. And within a very short period of time you had laws in most of the municipalities in the country that did in fact forbid smoking in publicly accessible space, in buildings. So that issue was hard-fought. I can recall that it was working its way through the various review bodies at EPA in the midst of the ‘92 election. And I received a couple of calls telling me how threatening this was to the party in five states and the governors who called for me to be dismissed in connection with that decision. But it had an immediate impact. I think we had some difficulty persuading everybody that was true because the confidence interval we had was 90%. Usually EPA's decisions are 95% and the reason we had the difficulty was we couldn't find a control group that didn't have evidence of nicotine and smoking in their systems. We finally found some nuns as I recall, discalced nuns in a convent in New Mexico as I recall. And they were largely free of any infection by cigarettes. But the rest of us, those of us who never smoked, it doesn’t really matter we all have evidence of carrying it.

Thinking about the oil industry and the – I remember George W. Bush; I did not serve in that administration I served in the first President Bush administration. He referred to oil as an addiction at one point. And I remember thinking that how do you deal with an addiction. I'm not aware that we've ever stanched addiction by cutting off supply. You’ve really got to go to demand, you’ve got to do the things that change that whole attractiveness of it to someone who's buying.

The oil company whose board I served on was the only American company whose CEO joined the United States climate action plan, that's ConocoPhillips. The other two who joined were both were BP and Shell, both foreign companies.

Greg Dalton: And that was a group of industry environmentalist trying to craft a central policy on the climate.

Bill Reilly: That’s right, come up with a proposal for legislation that would actually regulate carbon and do it with a cap and trade program. Environmental Defense Fund, Natural Resources Defense Council and others were involved with that. So that's not a company that ever was implicated in much of the story other than other than producing the product which continues to be something they do. I think the prospect that we have right now and a very important one, there is going to be a review that I think this fall of the president’s proposal commitment of the auto industry to support to 54 1/2 mile per gallon automobile fuel efficiency. Once that goes fully into effect it will result in more than 2 million barrels a day reduction in American consumption of oil. That is a hugely important decision. Every auto industry major auto industry and company except for Volkswagen has supported it. Yeah, I would think that they in their present circumstance might want to reconsider that decision. They have other fish to fry presumably, but that's hugely important in addressing this entire question.

Stanton Glantz: Can I just jump in on this? Because -

Greg Dalton: Stan Glantz.

Stanton Glantz: I was actually involved you are at the top on that 1991 EPA report, I was at the bottom. And that was a tremendously important document because the EPA identifying secondhand smoke as indoor air pollution just changed the way people thought about the problem from a personal health problem to an environmental problem.

And it caught it did it just transformed the discussion and the tobacco companies were absolutely terrified of that report; they brought their lawsuits they did this and that. But they then started a concerted effort to discredit the U.S. EPA. And they created something called the Sound Science Coalition to attack the EPA over the confidence in their votes. I think

Bill Reilly: They’re really good at naming, aren’t they?

Stanton Glantz: Yeah, yeah, well, I, yeah they really are I mean I teach statistics and actually you did use a 95% but we don't have time to get into that. But the point was that tobacco companies by then knew that they had such low public credibility that they couldn't be publicly identified with the Sound Science Coalition. So they reached out to other industries; to the petrochemical industry to the pharmaceutical industry to a whole – to the food industry, a whole range of industries that was potentially threatened by science-based regulation to provide cover for the tobacco companies who were calling all the shots. And then these other companies realized that oh, hey, this is actually a pretty good idea. And the same people who formed the Sound Science Coalition and set up these, you know, the denier scientists basically to try to discredit the EPA generally ended up going to work, not just for tobacco but for all these other companies and building the whole science denialists. So these things really do, you know, come together very tightly.

Greg Dalton: Bill Reilly.

Bill Reilly: Let me pose a question to Lowell if I might. It’s always bothered me. For so long science has been so clear, as was suggested by your citation of the science that the Exxon Mobil had itself. And yet the way the issue was reported was invariably to give voice to the deniers in every damn article. And that was, that contributed absolutely to the strategy that they had. There was no doubt no significant doubt after three we had eleven National Academies of Science report on this, we had –

Lowell Bergman: You’re talking about nicotine and cigarettes.

Bill Reilly: No, I’m sorry I’m talking about climate change.

Lowell Bergman: A climate change, okay.

Greg Dalton: It’s called the balance bias; the 97% of journalists, scientists get the same weight in a news article as the 3% who don't.

Lowell Bergman: I call it false balance.

Greg Dalton: Okay.

Bill Reilly: That used to be maddening to those of us in the environmental movement that what we would hear from the scientist was so definitive and then you see an article and there would always be the skeptical person quoted as a serious scientist very often; most of them were not as it turned out. But that has always bothered me in terms of reporting and I wondered it obviously is connected to the ethos of reporting, the ethics and?

Greg Dalton: Lowell Bergman.

Lowell Bergman: Money talks and all I can say is that the tobacco industry or industries in general in pursuit of their profit and maintaining their profit and the value of their stock in what they're doing will spend a huge amount of money to influence what's going on in news organizations. And people listen to the protests of attorneys and others about what's going on. In the tobacco situation the industry hired a public relations specialist who had been a journalist a man named John Scanlon. He was inside the offices of 60 Minutes, arguing directly with management and entertained and he would entertain them in the evening as well while I was out here in Berkeley. So the fact of the relationships that different news organizations have a certain level advertising, the advertising dollar, that model, it may in many ways be possible for some changes to take place because advertising no longer is a major factor in the news industry or it’s diminishing rapidly.

So I would say that it shouldn't surprise people that in the established media there is a great influence by what we would call multinational corporations or other people with great wealth and power. Look at the Republican candidates in the current election, right. So they are doubting climate they talk about climate change up as if it's not only not true, but it's some kind of conspiracy that people have made this up. And so, you know, and it's not even just debated you know in any way. So I think that I think one of the things that we have to accept is that the way public opinion is made in the United States and in most countries is not necessarily rational.

Bill Reilly: And in every one of the Republican debates you have not heard one word from Fox, CNN, or the others about climate change, not one single question even after Paris.

Greg Dalton: If you're just joining us, we’re talking about tobacco and the oil industry at Climate One today, I'm Greg Dalton. My guests are Lowell Bergman Professor at UC Berkeley, Stan Glantz, Director of the Center for Tobacco Control Research at UCSF. Ken Kimmell, President of the Union of Concerned Scientists. We just heard from Bill Reilly who was administrator of the U.S. EPA under the first President Bush.

I’d like to go to our lightning round in which we ask a yes or no question to each of our guests to get some quick thinking and make you slightly uncomfortable. Bill Reilly, Exxon is a superbly run corporation with high standards of precision and excellence, yes or no?

Bill Reilly: On safety and environment, yes. That’s what we learned in investigating the oil spill. They were considered the best.

Greg Dalton: Lowell Bergman, in the 1999 movie The Insider, Al Pacino plays you as a fierce journalist who's often shouting. Do you often shout like Al Pacino?

[Laughs]

Lowell Bergman: He’s also shorter than I am and older.

And I don’t have a blonde wife. So it’s a movie. No, and you don’t shout at your boss often and remain with the job.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: Bill Reilly, Shell oil has lost a boatload of money searching for oil and natural gas in the Arctic?

Bill Reilly: Yes.

Greg Dalton: Stan Glantz, scientists who wander into activism, risk losing some of their professional credibility in the eyes of their peers and the public?

Stanton Glantz: Well that’s certainly what big corporations would like you to think. But I think that when you are a scientist and you know something, especially if you’re a scientist at a public university, you have an obligation to tell people what you know.

Greg Dalton: That’s a no, okay. Science and activism can go together. Ken Kimmell, fracking kills the notion of peak oil?

Kenneth Kimmell: Fracking killed the notion of peak oil?

Greg Dalton: The world is awash and oil prices are low because there’s so much of it, environmentalists used to run around saying peak oil, we’re gonna run out we got to get off it; now there's so much oil we don't know what to do with it.

Kenneth Kimmell: The answer is no because it’s incomplete. You have to also include the reduction of demand due to the fuel economy standards and other things that are happening. And there’s a complicated set of reasons why oil prices have gone down and we’re washing them. Fracking is a piece of it but by no mean the whole thing.

Greg Dalton: Part of it. Stan Glantz, the war on drugs is a failure?

Stanton Glantz: Yes.

[Laughter]

That’s easy.

Greg Dalton: So follow up, it is futile to attack the supply of drugs, tobacco or oil; as long as there’s this demand, suppliers will satisfy it, yes or no?

Stanton Glantz: Yes, that’s why the California tobacco control program has worked so well. It's focused on making it so people don't want the smoke, the cigarettes. And that's how we should be dealing with marijuana too actually.

Greg Dalton: Bill Reilly, oil companies learned from the tobacco industry and made their nondisclosure agreements even stronger to foil people like Lowell Bergman.

Bill Reilly: It would appear, yes.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: Ken Kimmell, business leaders unfairly talk about environmentalists as though they are all of one mind when in fact they are not?

Kenneth Kimmell: True.

Greg Dalton: Environmentalists unfairly talk about oil and coal companies as a monolith when in fact they are not?

Kenneth Kimmell: Also true.

Greg Dalton: Last one. Bill Reilly, you wished that Al Pacino would play you in a movie?

[Laughter]

Bill Reilly: You know, I’d like to give some serious thought on who should play me in a movie. I’ll get back to you on that.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: Okay, we have a search underway.

Bill Reilly: I didn’t know he was so short until Lowell said this.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: Need someone taller to play you, alright. That’s the end of our lighting round. How’d they do, I think they did pretty well. Let’s give them a –

[Applause]

[CLIMATE ONE MINUTE]

Announcer: And now, here’s a Climate One Minute.

The link between tobacco denial and climate denial is more direct than you might think, as historian Naomi Oreskes points out. In her book Merchants of Doubt, she tells the story of Fred Seitz, a Cold War era physicist who was hired by R.J. Reynolds Tobacco to head up a program of what she calls “distracting research.”

Naomi Oreskes: So, for example, they would fund research on other causes of lung cancer, the link between asbestos and lung cancer, the link between radon and lung cancer, other causes of heart disease. So it was legitimate research but its purpose was to cast doubt on the links between the harms of tobacco and scientific evidence. He did that work 1979 to 1985. And then he founds the think tank with a group of other physicists, like himself, were also prominent physicists who have risen to positions of power and influence because of work they did in the Cold War.

But when the Cold War ends, they turn their attention to climate science. And not just climate science, but to a whole set of environmental issues that are quite familiar to all of us. Acid rain, the ozone hole, the role of pesticides in harming the environment, and they begin to challenge the scientific evidence on all of these issues. And the strategy they use is the strategy that Fred Seitz had developed working with R.J. Reynolds to cast doubt on the science to claim there's no consensus that we don't really know. And since we don't really know, it would be premature to do anything about it.

Announcer: That’s author and historian Naomi Orestes, speaking at Climate One in 2014. Now, back to Greg Dalton and his guests at The Commonwealth Club.

[END CLIMATE ONE MINUTE]

Greg Dalton: We’ve been talking about industry power; Bill Reilly, oil prices are very low. The industry is cyclical it’s been through lots of boom and bust. But how is the low oil prices right now unexpectedly low, affecting the industry?

Bill Reilly: Well, you know, my discovery as part of the co-chairman of the President’s Oil Spill Commission on the spill in the Gulf led me to conclude that one of the problems we saw there was the loss of some of the senior most people and best qualified people the last time the oil price was very low. People forget it got down into the single digits in the late 90s. Well, the companies did what they do in a cyclical industry; they shed staff, they offered outs to people and the most capable, those who would have other opportunities, took them, that is happening again.

That is happening in all the companies I'm aware of. They’re simply shedding staff. And to the extent that they are senior, experienced practitioners of oil and gas exploration and development. I think that's a very unfortunate consequence. The companies themselves by and large, the major ones that we’re familiar with can ride out the storm. But they’re then probably going to have to cultivate once the price does rise if it does anywhere where it used to be and I have some doubts about that, a new generation of people who are competent to keep us from experiences like Exxon Valdez and the BP Macondo spill.

Greg Dalton: Ken Kimmell, some environmentalists think that the oil companies got to be put out of business; other people, Mary Nichols, head of the California Air Board says that we need the engineering expertise and scientific talent that these energy giants have. What's the Union of Concerned Scientists think should be the future for oil companies to put them out of business or to transition them to something else?

Kenneth Kimmell: Transition them to something else. And really one of the reasons that we are raising these issues about the accountability campaign and making noise about it and seeking to hold companies responsible is we think, and we’re already seeing signs of this happening, that this pressure coupled with other economic factors can push them in a better direction. So I think it is still possible for major oil companies to make very, very meaningful changes to their business plan invest in renewable energy, invest in carbon capture and storage, stop the deception and start moving towards at least for as long as we need fossil fuels there is great gradations in the carbon footprint of different fuels, at a minimum really start moving towards the types of fuels that cause the least harm while we still need it.

And in the long run, though I do believe and the science tells us this is clear we have to un-addict ourselves to fossil fuels if we have any hope of meeting the goals that we just agreed to in Paris.

Greg Dalton: Your organization is also pushing for investigations of oil companies in California and New York, perhaps using RICO laws, which have been used in other cases, as what’s mentioned earlier. What do you expect to come from that and is there a kind of is there a deal to be made with oil companies like was what made with tobacco companies?

Kenneth Kimmell: I think there is, it’s not gonna happen right away. I think these investigations gotta play out. The tobacco settlements didn't happen right away either. It was after many, many years of people opening the courthouse doors and having them closed in their face and there was a lot going on. But I do think there is on the horizon, a global settlement here which involves the oil companies not just agreeing in principle to a carbon price but really supporting it, and an actual proposal getting it done. Putting aside funds to, especially for the most vulnerable countries in the world, preparing, augmenting the climate funds that nations have been pledging for that purpose and again switching their business to the most low carbon sources. So I think there is a deal along those lines to be had, but we’re a long ways from that right now.

And one of the first things that we want to see happen here and it is starting to happen, we want these companies to stop fighting every reform tooth and nail and stop funding those legislators who are fighting them. And I do think it's an encouraging sign that Shell and British Petroleum for example, have both said publicly that they’re leaving the group known as ALEC, which is a group that goes all around the country trying to convince state legislators that the reforms that they put in place that are actually working should be repealed. So I think we’re starting to see some signs that that this is starting to get some of it, some of the results we’d hope.

Greg Dalton: I want to roll some tape of Shell President Marvin Odum. He was here a while back and I asked him about climate change. Let’s hear what Marvin Odum, President of Shell Oil, had to say.

[AUDIO PLAYBACK]

Greg Dalton: Where is your position, Shell’s position on climate change and manmade climate change?

Marvin Odum: Well this is probably the easiest question you’ll ask me all night because it’s very clear for us as a company and that is that climate change is real, that humans have an enormous impact on that and that it requires some sort of action going forward.

Greg Dalton: And what kind of risk does it present for the United States and for Shell as a company?

Marvin Odum: Well, I think if you look at the policies that we advocate as a company. So getting outside of our direct day to day business, working with governments around the world that I’d say the number one element of that advocacy is putting a price on carbon.

[END PLAYBACK]

Greg Dalton: So Bill Reilly, I’d like to ask you, I think you know Marvin Odum. Marvin Odum, President of Shell Oil saying the company wants a price on carbon and they say that quite consistently publicly now. Yet there are part of organizations, American Petroleum Institute, which work pretty hard to make sure that doesn't happen.

Bill Reilly: I don't think they’re major players at American Petroleum Institute for my experience. But that's true that they have come out for a price on carbon. They have a $75 virtual prize shadow price. I think Exxon has a bigger one, company I was associated with at a $25 price many years ago. So that's going the right direction and what that means is when they make an investment they have to assume that there will be a tax of that amount and that the investment will still return positive interest to them. So they're getting ready for it, clearly. In fact, one of the interesting things to me is how much farther the oil industry is particularly those companies than the Congress in recognizing the need to impute a carbon price.

Greg Dalton: Ken Kimmell, your thoughts on that? Oil companies getting ready and how they’re actually further ahead than some of the politicians.

Kenneth Kimmell: So we are aware of the shadow price. We think that's a positive development, but this is again one of those tricky things. Exxon Mobil also says that it favors carbon pricing and if you go to its website, you'll see that. We just put out a report two days ago though that tracked the votes of various legislators who voted on actual carbon tax revenue neutral carbon tax proposals, which is what Exxon Mobil says it wants. And it turns out that about 80% of the legislators who voted no to those proposals are getting campaign contributions from Exxon Mobil. So it just doesn't feel like they’re at a stage where they're putting their resources behind what they say. And one has to wonder, because they are such an effective lobbying group; if they really wanted a carbon price you would think they'd be able to make some progress in the Congress getting one with all the resources they have to bear. So I do think and again this is important not to talk about all these companies as if there one, I think there's important distinctions. I think some mean it more than others. But I do believe that these companies do stand in the way of some of the policies that they say on their websites they favor and that’s a big problem.

Greg Dalton: Stan Glantz.

Stanton Glantz: This is another similarity to the tobacco companies because they said for years publicly we don't want kids to smoke. But when you look in their documents at the marketing they’re figuring that it's like the teenager is the future of our industry. And I think that – I mean I agree with Lowell that the petrochemical industry is different from tobacco. If we could snap our fingers and be rid of tobacco that would be great. We need the energy industry. But the one thing they have in common is that they are both trying to maximize profits in the short run, and by doing that they fight regulation. And so the company – and it's just like the same thing the tobacco companies if you look at their websites, they’re all for health, they’re now admitting smoking causes disease, partially because the federal court ordered them to admit it. But you then have to look at like what they actually do. And as I watch what’s going on in the climate debate, I still see deniers out there. I still see them being funded by the petrochemical industry and I still see the industry doing everything they can in terms of their actual political actions to slow progress. And, you know, I think the lawsuits that are being talked about now by a couple of the state attorneys general are very, very important because those lawsuits and the discovery in those lawsuits is really which changed the tobacco debate.

And I think one of the real heroes in the tobacco story was Skip Humphrey who was the Attorney General of Minnesota. Who did huge amounts of discovery during the Minnesota lawsuit against the tobacco industry. And Skip used to say to me the most important thing to come out of this litigation is the truth. And as part of the Minnesota settlement they forced about 30 million pages of internal industry documents into the public domain; they’re all sitting on a website at UCSF now. And that created the expectation in tobacco litigation that any documents produced would be made public, and we’re up to almost 90 million pages now.

And that was very unusual. Normally in litigation when the case settles all the discovery is destroyed. And I think it's tremendously important to establish an expectation that the state attorneys general who are moving against the energy companies to publicly go on record saying that if there is a settlement those documents will be made available to the public. And I mean I would love to put them on our website at UCSF when the time comes.

Greg Dalton: Lowell Bergman.

Lowell Bergman: Yeah, but I think that we have to come back to your point about the news media and the coverage of the issue. Think about how many hours of public television have you seen on any program in the last decade about the problem of not only climate change but of the energy industry or the energy question. The idea for example, after 9/11 there was some reporting that we did get to do about Saudi Arabia and the problem that we are that Saudi Arabia - that 15 of the 19 hijackers came from Saudi Arabia and Saudi Arabia is being supported by our consumption of oil. And that issue of what's going on in the Middle East and what oil, the role that oil plays in all of that that's going on. There’s very little in the public media in the new in the broadcasting industry in general and in print that gets out to a large number of people. And on the radio you have deniers.

So you have a fundamental media problem and I don't think that politicians or others have addressed that directly. People who work in the industry have a hard time selling a story that has such a serious question. And that will jeopardize potentially the profits of the organization they work for.

Greg Dalton: Lowell Bergman is a professor of investigative journalism at the UC Berkeley. Other guests today at Climate One are Stan Glantz, Director of the Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education at the University of California San Francisco. Ken Kimmell, is the President of the union of Concerned Scientists and Bill Reilly, was administrator of the U.S. EPA under the first President Bush. I'm Greg Dalton. You can join the conversation using our twitter handle @climateone.

Let’s turn to our audience questions. We’re talking about the oil industry and the tobacco industry at Climate One, welcome.

Male Participant: Hi, my name is Paul Pasiminio [ph]. I actually have asked the question before but I appreciate the chance to do so again. As someone who works in an organization that’s been targeted specifically by an oil company using the RICO Law to try to suppress our free speech, that’s Chevron and Amazon Watch, I wonder if you guys could talk about some of the harsher, dirtier tactics you see these companies getting ready to and are likely to employ against people, individuals organizations, et cetera even the government to try to suppress the story that they don’t want told. .

Greg Dalton: Thank you. Stan Glantz, some of the hardball?

Stanton Glantz: Oh yeah. They sued the University of California twice trying to shut our work down; UC stuck up to them and won. I just had another yet another freedom of information act request put in about our research. So there they are there; just Google me, and you'll find out what a terrible person I am. And no, these are people who, I mean when you talk about smoking or when you talk about moving away from traditional fossil fuels, every little success every little, you know, every cigarette that isn't smoked we view as a public health success. That's money out of the pocket of some big cigarette company. And there's no question that the work we've done and others has cost the tobacco companies, you know, tens of billions of dollars in lost sales. And I think as they're forced to move away from traditional fossil fuels and to renewable energy they're going to be less profitable and they're not gonna like that. And if they would be more profitable doing it, we wouldn't be having this conversation because they would've done it. And so they’re gonna do everything they can to fight this change because their goal in the end, they're not philanthropies they’re out to make money.

Greg Dalton: Lowell Bergman on that.

Lowell Bergman: Just quickly to answer your question. If you take on a major corporate interest or people of great wealth as a journalist, you should expect that you’re gonna get pushback. They'll have lawyers to look at everything you do and occasionally they'll even sue or more things will happen. We do have another precedent at the University of California we had a panel year and a half ago at our program our annual symposium, where a short seller from New York Jim Chanos who is part of a story we were doing about Macau and American casino companies operating there, he made some statements, statements which he was sued for defamation for what he said in an academic conference at the University of California it’s the first time in the history of the state. Steve Wynn sued him for libel. Now luckily in California we have slap statutes and the suit was summarily dismissed twice. And Wynn will have to pay a half-million dollars in legal fees of Mr. Chanos defending himself because he picked the wrong person. But that kind of retaliation, that kind of activity is pretty normal in our business and one of the reasons people are hesitant to publish and get into these areas, especially if you're going to be alleging for instance RICO violations or some kind of conspiracy and you'll have to stand up and defend it.

Greg Dalton: Bill Reilly.

Bill Reilly: I have had experiences where scientists gave me advice quietly about the efficacy or bad effects of a pesticide or chemical or something in that sort.

And then declined to say publicly later what they had advised me to do. And I would talk to them about it and more than once they said look, it's not worth it, you know, you’ll get quoted out of context, you'll be understood to be much simpler than the explanation you give and that sort of thing. And we also made a decision; I made a decision once to get into looking seriously at lead and its impact on health and the environment. There was a very distinguished I thought researcher who basically was associated and drove that subject who nearly was destroyed his career, and I remember when I was going up to the hill to defend that decision and explain it to the Congress, I proposed that he go with me. And I remember a staff said “Do you really want to sit next to him after all the things that have been said about him?” And I said I think particularly because he’s very important to the decision and his research. So people do pay a price, there’s no question scientists pay a price and it does I think very often cause them to think well I’d just as soon stay out of it if it's hugely provocative and controversial.

Greg Dalton: Let’s go to our next audience question. We’re talking about the oil industry and the tobacco industry at Climate One.

Male Participant: Hi, my name is Wayne Roth. This is directed to Mr. Kimmell. Many years ago you put out a little paper saying that the Sierra snowpack would possibly reduce to 5% by 2090 somewhere in that neighborhood. And last year the Sierra snowpack was at 5% and although we’ve had an El Niño event recently I heard Peter Glick mention that actually the Sierra snowpack is now below normal because of the last six or seven, 10 days of hot weather. Can you comment and can the whole panel comment on the difficulty of getting people to understand how quickly climate change is becoming more and more disastrous and the effects, how they will get worse quickly and that we have maybe a decade to get off of fossil fuels. So all of this talk about well, oil companies will maybe get off or maybe not, this addiction that that Greg mentioned or someone else mentioned, we don't end this addiction it's gonna end us.

Greg Dalton: Thank you. Ken Kimmell.

Kenneth Kimmell: Yeah, well your question said a lot there. First of all, you're absolutely right that one of the most scary things about climate change is the way the early modeling is being validated except the effects are happening much more severely and much more quickly than those models actually predicted. A second element of the scary nature of it is the synergistic effects and the fact that climate change begets more emissions it begets more climate change. So all of that is extremely scary. I mean I do, I would say this. I think that groups like ours, and many others, and also a continued emphasis with journalists on attacking this notion of false balance and not having, you know, the climate denier debate that the actual climate scientists, it is making a difference.

If you look at public opinion polling, the majority of people of the people who believe that climate science is a serious problem and needs to get addressed is going up. It's especially going up amongst young people even Republican voters under 40. About two thirds of them say they accept the science and they think less of candidates who deny it. So this is changing but again, the problem is the political system is not changing nearly fast enough to get us to where we need to be. And that to me is what is so sad and tragic about the examples of deception that I talked about, which are 20 years old. Because you can imagine that if that didn't all happen, if public opinion didn't get so polarized, we might've actually made some real progress and we wouldn't be in a position now where we are running out of time and all the things that we need to do to address climate change are now much more expensive. And that's the real tragedy. I mean, I think we all have to remember and I'm sure Bill Reilly remembers this; when George HW Bush ran for president, he said we’re going to fight the greenhouse effect with the White House effect. Can you imagine any of the Republican candidates running for president saying that now? And so things have totally changed. And fortunately people are finally getting up but we've lost a lot of time and that is just the tragedy of it.

Greg Dalton: We have to wrap it up there. I want to end on an upbeat here. We've heard about some of the urgency and the fierceness of science; starting with Lowell Bergman, what gives you hope that humans will make this transition and adapt to climate change in a way that’s in time?

Lowell Bergman: Gives me hope? I'm not sure I have much actually. I think that the challenge that this presents people with, for instance just the media world, is really high. If you're talking if you’re to believe that there’s a point of no return it won't matter what we do. I think that we've allowed the situation to get to a point where it may in fact have to endure tremendous discomfort and maybe disaster before the kind of action that's needed will be taken.

Greg Dalton: Journalists are always half-empty guys. Speaking as one, I’m right there with you.

Lowell Bergman: I’m used to people ignoring my stories.

Greg Dalton: Bill Reilly.

Bill Reilly: You know, my own history in the field of the environment gives me a lot of confidence that we’re gonna address this problem. If you look at the situation that the country in much of the certainly the developed world confronted 40 years ago, it's vastly different. The quality of the air, quality of the water, the fish returned to streams, there’s so many measures by which you can say culture did get together. I think that the youth had a – who are no longer the youth, many of them. Many of us were young once, really did have a great success story in our past. Success story in the environment and so did other places. And I think building upon that, building upon some the agreements that have been reached, the history of agreements in international and important environmental questions such as the one to protect the ozone layer is you start small and you move beyond. And the next time we reconsider that treaty I can almost assure you it will go further. We will know more, there’ll be better technology, we’ll have more experience with pricing and other alteratives and I think we will address the problem.

Greg Dalton: Stan Glantz.

Stanton Glantz: Well, I got involved in the tobacco issue when you could still smoke in elevators. And when Benson and Hedges the first ultra-long cigarette had a national ad campaign, it was a running gag about the door closing on the cigarette. And we now in the world where, I mean that is when you tell it to students today they look at you like you're crazy. I think there's been tremendous progress made on the environment too when you look back. I think that that the one thing that’s very scary, which was Lowell mentioned is I think – and also Ken, is we’re getting into some nonlinear effects and, you know, the question is will people figure this out fast enough before we have a complete disaster. But I think the public is way ahead of the politicians. I think that the Citizens United and the dominance of the political process by big money is a huge problem. And you know, I'm just hoping that in those lawsuits the energy industry documents come out because the tobacco documents have made a huge difference in changing the discussion and forcing the companies to behave differently and making it harder for the politicians to do their bidding.

So I think it's very scary but, you know, right now we’re living in a world that 30 or 40 years ago a lot of these issues would've been viewed as impossible. So I'm hopeful.

Greg Dalton: And the lawyers will save us. Okay, Ken Kimmell, you’re a lawyer.

Kenneth Kimmell: I don’t know if the lawyers will save us. But what gives me hope is, I was in Paris I was privileged to be there and I saw 195 countries, basically the entire world, agree on a course of action. I believe that is the first time in human history that that's happened. That gives me hope. It also gives me tremendous hope to see just how much the price of renewable energy has fallen to the point where it is really within striking distance of being competitive with fossil fuels and that's obviously critical. But at the same time, everything hangs in the balance right down to the fact that we have apparently four judges of the Supreme Court who seem inclined to strike down the clean power plan and four who are gonna seem designed to preserve it. An election coming up, we don't know how that's gonna turn out.

So I feel energized by Paris and by the economics, but this has a huge question mark. And what happens politically in the next 5 to 10 years I think is going to decide whether we’re going to stem the worst effects of climate change, or whether the Paris agreement is going to get stalled right out of the gates. And I think we don't know the answer to that yet.

Greg Dalton: So stay tuned to Climate One to find out how it goes down. We have to end it there. Ken Kimmell is President of the Union of Concerned Scientists. Our other guests today at Climate One have been Bill Reilly, administrator of the U.S. EPA under the first President Bush, Lowell Bergman, professor of journalism at UC Berkeley and Stan Glantz, who’s a professor at UCSF. I'm Greg Dalton. You can join the conversation on Twitter using our handle @climateone. I’d like to thank our audience here at the Commonwealth Club and online and on air. Thank you all and thanks to our guests for joining us today.

[Applause]