Concussions, Cigarettes and Climate

Guests

Adrienne Alvord

Steve Fainaru

Stanton Glantz

Summary

What do football, tobacco and oil have in common? A common narrative of deceit. When tobacco companies faced public scrutiny about the link between cancer and smoking, the industry launched a campaign questioning the scientific evidence. Oil companies and the National Football League have used the same playbook to mislead the public. Listen to the stories of how industries endeavor to confuse.

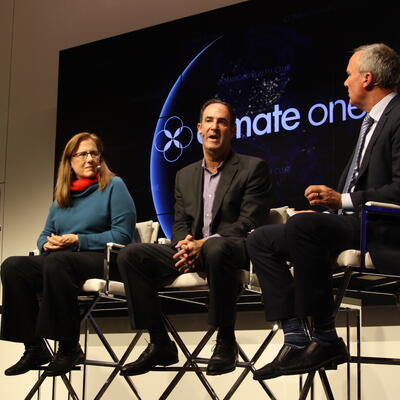

Adrienne Alvord, Western States Director, Union of Concerned Scientists

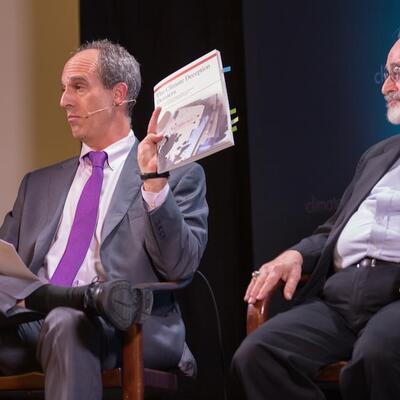

Steve Fainaru, Senior Writer, ESPN Investigative Unit; Co-Author, League of Denial

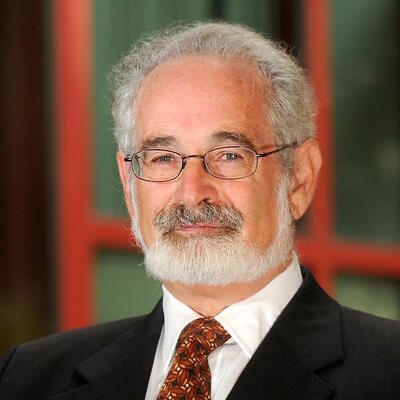

Stanton Glantz, Director, Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education, UCSF

This program was recorded in front of a live audience at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco, CA on November 29, 2017.

Clip courtesy: Union of Concerned Scientists

Full Transcript

Announcer: This is Climate One, changing the conversation about energy, economy and the environment. When doubt is your product, business communication can look a lot like a football game.

Adrienne Alvord: There is the fake, the blitz, the diversion, the screen, and the fix.

Announcer: These are some of the disinformation strategies used by industries when scientific evidence begins to show that their product causes harm.

Stan Glantz: They know the science, they accept the science internally. They use it to make business decisions that the public positions they take are completely 180 degrees away from what they're doing.

Announcer: From smoking tobacco, to burning fossil fuels, to bone-crushing football tackles.

Steve Fainaru: These are things we know intuitively can't be good for you, right. And so they’re trying to make this case that somehow like what is right in front of us might not actually be true.

Announcer: Concussions, Cigarettes, and Climate: Narratives of Deceit. Up next on Climate One.

Announcer: What’s the connection between football, tobacco and fossil fuels? Welcome to Climate One – changing the conversation about America’s energy, economy and environment. I’m Devon Strolovitch. Climate One conversations – with oil companies and environmentalists, Republicans and Democrats – are recorded before a live audience, and hosted by Greg Dalton.

In the 1950s tobacco company researchers realized the connection between smoking and cancer. To protect their jobs and profits, executives created a sophisticated campaign to cloud the emerging medical science. One tobacco executive captured the essence of that campaign when he observed, “Doubt is our product.” In the 1990s, oil companies picked up the tobacco playbook to sow doubt and confusion about the simple fact that burning fossil fuels releases heat-trapping gases that are destabilizing the Earth's operating system. Lately the NFL has called some of the same plays, as evidence mounts that repeated collisions in football and other contact sports turn brains into Jell-O.

Today’s guests all have direct knowledge of these narratives of manufactured doubt. Adrienne Alvord is Western States Director at the Union of Concerned Scientists, a nonprofit group founded at MIT that defends the integrity of science. UCS recently published The Disinformation Playbook, showing how companies deceive citizens and harm public health and safety. Steve Fainaru is co-author of League of Denial: The NFL, Concussions and the Battle for Truth. He received the Pulitzer Prize for his reporting for the Washington Post from Iraq, and currently is a writer for ESPN, where he’s broken many stories on the concussion crisis in football. And Stan Glantz is a professor at the UC San Francisco medical school. He’s an international expert on tobacco control, and published documents from tobacco company Brown & Williamson to prove that companies knew 60 years ago that nicotine was addictive and smoking causes cancer. His many books include The Cigarette Papers and The Tobacco Wars.

Here’s our conversation about Concussions, Cigarettes, and Climate -- Narratives of Deceit.

Greg Dalton: Stan Glantz let’s begin with you. The tobacco wars were kind of fought in the 90s but they’ve been in the newspapers again for those of us who can’t print newspapers and perhaps online. There are ads running in national publications now about tobacco and health impacts. Why are those ads being run now years after the litigation?

Stan Glantz: Since the 1950s, the tobacco companies engaged in a systematic and industrywide campaign to distort the science to keep the public confused and basically defraud the public in order to keep them smoking. And during the Clinton administration the Department of Justice initiated a lawsuit under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, the RICO law which is designed to prosecute organized crime. And the government successfully claimed that the tobacco companies had created an illegal enterprise where they were coordinating their efforts to perpetrate this fraud. The case went on for many years in 2006, the government essentially won the case and federal Judge Gladys Kessler ordered them to stop saying nicotine wasn't addictive to stop denying the evidence linking tobacco and cancer. She ordered them to continue producing their internal documents which we put on the web at UCSF for everybody to look at. And she also said they had issues which she called corrective statements. They had go to the public through the mass media which you know back in 2006 was radio, television and newspapers and admit that they had misled the public that they had design cigarettes and a way to manufacture addiction that secondhand smoke was dangerous. And now 11 years ago after 11 years of continuing litigation where the companies are trying to avoid being required to make these statements we finally got them. And they’re gonna be running I believe for a year.

Greg Dalton: Adrienne Alvord, tell us where the tobacco story connects to the climate story then the fossil fuel story.

Adrienne Alvord: Well, as Dr. Glantz was saying the tobacco industry really pioneered the techniques that are used in a disinformation playbook to deceive the public about the science that their products are causing harm. And so when it was becoming clear in the 1970s and 1980s, in particular that fossil fuel combustion was leading to the greenhouse effect which caused global warming. The fossil fuel industry organized itself they understood that the science was settled about this phenomenon, but they also understood that it was complicated and that they could forestall action primarily government regulation and possibly as with cigarettes liability if they confuse the public and policymakers about the causes. And so they took a big leaf out of the tobacco playbook in that they use the very same techniques which involve funding of false science, hiring scientists to produce information and research and not disclose that it's being funded by the fossil fuel industry, contributing money to prestigious institutions and hiding behind the names of those institutions when actually the research that's being produced is diverting attention from what’s causing harm of course they’re doing a lot of lobbying. And they're sending a lot of signals to the public, which are very, very confusing about whether or not the science is really settled. Whether or not the models are accurate whether there might not be some advantages to global warming. Maybe we can farm in different parts of the country where we can't now. Things like this, things that really make the public feel like well we know there's something going on but we’re not really sure if it's good or bad, and we’re not sure what the best thing is to do about it. And that's still going on today.

Stan Glantz: And it’s a lot of the same people by the way that the tobacco companies used.

Greg Dalton: In fact, there's one lawyer Arthur Stevens was legal counsel for Lorillard Tobacco and he was brought into the football situation by Preston Tisch, owner of the New York Giants. So that’s one of the connections between football and tobacco. Steve Fainaru, many ways that football story goes way back but one of the real central character that you mentioned in your book in the excellent Frontline documentary is Mike Webster. So for those of us who are not familiar, want a refresh tell us Mike Webster the story and what's so important and compelling about him and the concussion.

Steve Fainaru: Well Webster was essentially patient zero in the NFL's concussion crisis. He was a center for the Pittsburgh Steelers for 17 years and he was known as a player who was intelligent and savvy. He was sort of the second captain of the Pittsburgh Steelers offense, which was quarterback by Terry Bradshaw. He very much had his life together, but toward the end of his career his family started noticing significant changes and he just wasn't taking care of his finances. He was incredibly forgetful. He had incredible mood swings and would become violent with his family. And then soon enough, he was completely estranged from his family and homeless and basically living out of his truck. Some of the more extreme behavior that he went through was, you know, he had insomnia and so he would have his son use a taser to put him to sleep at times. And then finally he died at the age of 50 and he was taken to the Allegheny County Medical Examiner’s Office where a young pathologist named Bennet Omalu who just happened to be working that day and he was incredibly curious. And he was not a football fan but he knew a little bit about Webster's case history and he decided during the autopsy to cut open his skull and preserve his brain and study it. And what he found was the very first case of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, which is a brain disease that had previously been associated only with boxers in Webster. And so it was the first case in which an NFL player had been diagnosed with CTE or brain damage related to football.

Greg Dalton: Since there’s been many others who’ve committed suicide and had lots of similar problems we’ll get into some of those later. Chris Borland was a linebacker for the San Francisco 49ers, who abruptly walked away from the NFL. Here is a video created by the Union of Concerned Scientists. Let's listen to Chris Borland.

[Start Clip]

Chris Borland: My name is Chris Borland. I walked away from pro football and a $2.9 million contract with the San Francisco 49 ers because I didn’t want to develop CTE or chronic traumatic encephalopathy, which is caused by repeated brain injury. Researchers at Boston University studied the brains of 111 deceased NFL players. They found CTE in 110. CTE is a brain disease that causes depression, aggression, dementia, and in some cases suicide. Yet for many years, the NFL denied the link. Unfortunately, the NFL isn’t the only powerful player that’s sidelining science. Lobbyists in many industries are paid handsomely to convince lawmakers to undermine science that protects our health. We all need to speak up and make sure that science isn’t sidelined because when powerful interest keeps science from the decision-making process, people get hurt.

[End Clip]

Greg Dalton: That was former San Francisco 49ers linebacker Chris Borland. Steve Fainaru, you spent a lot of time going around Chris Borland. Tell us, you know, how he came to that decision.

Steve Fainaru: Well, it’s kind of crazy actually. Borland read our book and he claimed that he was like, something he was reading during the NFL season and, you know, he wouldn’t like he had it in his locker room but he had to hide it. And then at the end of the season, I didn’t know him but he called me and he said he was interested in talking to some of the neuroscientists who were in our book. And so I pass along some contact information not really thinking, I asked him, he’s like, “Oh I’m just doing some research.” And then two months later he called me and my brother who’s also my colleague and he and I worked on this book together and he announced that he was -- told us he was retiring. That after one season he'd been incredibly successful, he had been the leading tackler on the 49ers and he was actually a candidate for rookie of the year. And he was set to make like $3 million and he just decided to walk away from the NFL and basically he said he'd compiled enough information reading and talking to people that he just didn't want to take the risk.

Greg Dalton: The NFL has been doing research on this. So tell us how the NFL, Steve Fainaru, their journey they've gone on the research looking into the CTE after Mike Webster kind of blew the case open and made it, you know, Will Smith play, there’s a feature film Hollywood film they told that story. How is the NFL handled the research?

Steve Fainaru: I mean it’s been a kind of a 20-year saga at this point, you know, to sort of condense it. I think one of the things that’s really striking to me, I was listening to the stories is just the same patterns over and over. And they’re trying to convince and a lot these cases is particularly true of smoking and football, and these are things we know intuitively can't be good for you, right. And so they’re trying to make this case that somehow like what is right in front of us might not actually be true, and that was really the case with the NFL. I mean in the NFL’s case initially they put together their own, they call it the Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Committee and they assigned --

Greg Dalton: Wait, wait. Mild Traumatic --

Steve Fainaru: Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Committee. And it was composed of primarily NFL physicians, including the team doctor for the New York Jets who was actually a rheumatologist. So he was the head of the committee and, you know, and he was also, Paul Tagliabue was the NFL Commissioner at the time he was Tagliabue’s personal physician. So this Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Committee they put out 16 papers which are published in the neurosurgery journal and they basically said in a nutshell that football players don't get brain damage that there are essentially impervious as if they’re like superhuman. And that concussions are actually very minor injuries and that people can go back into games that it's okay for high school players to play with concussions or to return after concussions that these are very mild injuries. So that went on for about a decade and then they were ultimately -- and what happened was it was an accumulation of evidence that more and more players were coming up with problems. After Webster there were several more cases. Now the numbers of cases are in the hundreds but they just couldn’t sort of, you know, it was sort of undeniable at certain point they had pressure from Congress which compared it to the tobacco industry problem. So then they shifted into a completely different phase which we've been covering for the last few years. And that has been trying to sort of co-op the federal government. They gave $30 million to the NIH which was supposed to be an independent they were handing it over to the independent experts and they’re gonna let the experts decide. But then when push came to shove and the NIH handed over half the money to a neuroscientist at Boston University who had very clearly drawn a link between football and brain damage, they revoke the funding, pushback and try to get the money diverted to doctors who are affiliated with the league. So that sort of been their playbook over the last few years and it continue right up to today.

Greg Dalton: Stan Glantz, as you’re listening to this, is this like déjà vu all over again?

Stan Glantz: Yeah. I mean just about a month ago Philip Morris created a “independent foundation” for a smoke-free world to show what great guys they are. And you listen to the rhetoric that they are gonna be independent and their charter says that, you know, the fact that they're getting $80 million a year from Philip Morris there won’t really give Philip Morris any influence and, you know, the person who runs it actually is an old friend of mine, a guy who used to be an anti-tobacco guy at the WHO who went over to the dark side, well actually his transition to the dark side is now complete, because he went from tobacco to working for Pepsi to get Pepsi to make healthy beverages and then he went on back to work for the tobacco industry. But, you know, the reality is that if they did one thing, it's exactly the story Steve was talking about, if they did one thing that actually risked hurting the tobacco companies that money would just be gone like that. And in fact back in the 70s and 80s the tobacco companies give a bunch of money to Kaiser, the Kaiser health plan because they have a big database of, you know, lots and lots of patients and they were saying we’d like you to look at every possible thing that might cause heart disease and hoping they would find that smoking wasn't important after they considered everything else imaginable and they found smoking was important. And the guy who did it was just an assistant professor appointment at UC, you know, he published this and the industry tried to talk him out of it and he said this is what we found we’re gonna publish it. And so they then setup a whole PR campaign to trash the guy. So it all sounds kind of vaguely familiar, you know. The one thing about these guys also if you look at the global warming issue. They’re not very creative and they just keep doing the same things over and over again and I do think the public is beginning to figure that out.

Announcer: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation about Concussions, Cigarettes, and Climate -- Narratives of Deceit. You can subscribe to our podcast at our website: climate one dot org. Greg Dalton will continue his conversation in just a moment.

Announcer: We continue now with Climate One. Greg Dalton is talking about football, tobacco, and fossil fuels with Adrienne Alvord, Western States Director at the Union of Concerned Scientists. Steve Fainaru, co-Author of League of Denial: The NFL, Concussions and the Battle for Truth. And Stan Glantz, professor at the UC San Francisco medical school, and author of The Tobacco Wars.

Here’s your host, Greg Dalton.

Greg Dalton: Adrienne Alvord, tell us the playbook. What are the plays in the playbook that the Union of Concerned Scientists has identified and this is not just oil and tobacco as other industries. Tell us the plays.

Adrienne Alvord: Okay. So we created this playbook so that people could have a better sense of understanding of these strategies these communication strategies --

Stan Glantz: You’ve got to find this on the web. It’s so good.

Adrienne Alvord: -- that have been used for six decades or so the tobacco industry was really the pioneer. And the strategies are called in order for people to understand we sort of name them after football strategy. So we've got the “fake” which is basically taking fake scientific research and trying to pass it off as the real thing. We have the “blitz,” which to me is the most personally distasteful. It's when corporations try to not only besmirch the science but they take the scientists and, you know, run their names to the mud and try and attack their credibility and harass them in various ways, including suing them, and other kinds of legal harassment sending them nasty crude emails and basically not only making their lives miserable but becoming an object lesson to other researchers who might want to follow the same path. Then there is the diversion which is very widely followed. This is when corporations will take settled science and through a variety of communications tactics will sow doubt about what is really settled science and make people feel like oh the science maybe isn't certain. Then there's the “screen” which we’ve had some examples of where corporations will fund research at prestigious institutions and those institutions give them more credibility. But the research is actually diverting attention from the harm that their products are causing. And then there's the “fix” which is kind of the most open crude exercise of raw political power to try and influence regulators and legislators to ignore the science and not find them liable and not regulate them. So those are the things that we identified. I think you could find subgroups a lot of times these are used in concert. I think that the petroleum industry has used probably everyone of these to slow down progress on climate change. But the main thing that I think is important, you know, these are kind of cute names and some of these stories are actually kind of funny. But this disinformation delays action that we need to stop harm it’s delay causing devastation, personal devastation sometimes communities, public health and in the case of climate change the whole planet. So it's not just fake news. It really is something far more insidious than that. It's something that's causing harm and I think we need another term besides fake news.

Greg Dalton: Stan Glantz, there’s a difference and we’re talking about risks people are willing to take. People are willing to take the risk of cancer to enjoy smoking, willing to take the risk of concussion, a brain-damage to play football. So if humans are willing to take very personal risks for things that they find enjoying then climate change seems like that's an easy one because the benefits are personal, but the costs the externalities are socialized. So it sounds like what we’re hearing here is that climate change is gonna be tough to solve but we’re doing personal harm on these other things.

Stan Glantz: Well, I think they’re actually quite strong parallels because the basic strategy that you see across all three of these examples is the effort to just simply slow progress down. Because, you know, the tobacco companies know that people are quitting smoking that sooner or later they're going to be forced out of business. But if they could just extend that a year or two or five or 10 just slow the rate of decline a little bit that's like billions and billions of dollars that they made. And, you know, if you look at global warming, I can't believe that the Koch brothers don't believe global warming. It’s real, they’re smart guys, they’re engineers. But if they could just slow -- and the transition to renewable energy has to happen but if they could just make it happen a little bit slower then they can make a ton of money in the meantime. And I think that's what underlies all these strategies it’s just rather than speeding public understanding of the truths of what we’re talking about, which would then build political support for the kind of policy changes that would solve the problems they just want to slow everything down as much as they can.

Greg Dalton: Adrienne Alvord.

Adrienne Alvord: I think what you’re really talking about is that I think the difference between playing football and smoking a cigarette and solving global warming is that those two activities are more or less volitional. Leaving aside of course that tobacco is addictive that's a bit of a wrinkle.

Stan Glantz: Yeah. And secondhand smoke too.

Adrienne Alvord: Yeah that's true. But more or less these are individual choices that people make to engage in these activities. Whereas, you know, it's hard to walk away from the entire economy. And I think that, you know, we need to do a better job of helping people to identify what is good information and what is junk information. I think that's the crux of this issue.

Greg Dalton: I’m Greg Dalton and this program of the Climate One at the Commonwealth Club. We’re talking about football, tobacco and oil. My guests are Adrienne Alvord from the Union of Concerned Scientists. Steve Fainaru, a reporter for ESPN and Stan Glantz, a medical professor at the University of California at San Francisco. We’re gonna go to our lightning round I’m gonna mention a noun to our speakers and ask them to respond with their first thought that comes to their mind, unfiltered and perhaps irresponsibly. Steve Fainaru. What comes to mind when I say Junior Seau, former linebacker for the San Diego Chargers?

Steve Fainaru: Tragedy. I mean Junior Seau’s death was just unbelievable tragedy. I mean he was a wonderful person. He was a good citizen. He was an incredible athlete and his brain was destroyed by football and he ended up killing himself.

Greg Dalton: Adrienne Alvord. What’s the one word that comes to mind when I mention President Trump’s science advisor?

Adrienne Alvord: One word? Ignore.

Greg Dalton: He hasn’t appointed one so. Stan Glantz. What’s the one word that comes to mind when I say Altria?

Stan Glantz: Slime bucket.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: Adrienne Alvord. What's the most effective climate denier that you know of, a skilled prince of darkness?

Adrienne Alvord: Marc Marano. Anybody see Merchants of Doubt? This is a guy who started his career he majored in communications started his career working for Rush Limbaugh. Then he went to work for a right-wing news outfit that was responsible for publishing and promulgating the story of the Swift Boat Veterans for Peace and trying to undermine John Kerry's war record. And then he went to be I think the communications director for James Inhofe and then he opened his own climate website and started passing himself off as a climate expert. And in Merchants of Doubt he’s absolutely gleeful about not really being a scientist but I play one on TV. And the problem with this guy is that, you know, he’ll say anything. And if you look at his career it’s very clear he's a right-wing PR flack, but he marketed himself as a climate expert. And so he went on TV and was equally weighted with, you know, the fairness doctrine, you know, you got to have two sides to everything. You have a climate scientist on one side a real expert and you have this guy who’s there basically to spout propaganda. So he’s been, he and his ilk have been very effective unfortunately.

Greg Dalton: Steve Fainaru. One word that comes to mind when I say NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell?

Steve Fainaru: Equivocator.

Greg Dalton: Stan Glantz. New England Patriots.

Stan Glantz: I don’t have a clue.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: Adrienne Alvord. Clean coal.

Adrienne Alvord: [Laughs]. I think that’s my answer.

Greg Dalton: Okay. True or false. Stan Glantz. Sugar is what keeps every human being alive and with the energy to face our daily problems. True or false?

Stan Glantz: The way as you framed it, false.

Greg Dalton: Adrienne Alvord. Carbon dioxide is food for plants?

Adrienne Alvord: True, but.

Greg Dalton: Okay. Steve Fainaru. There is no such thing -- true or false. There’s no such thing as the safe amount of playing tackle football?

Steve Fainaru: True.

Greg Dalton: Adrienne Alvord. True or false. You vividly recall smoking your first cigarette?

Adrienne Alvord: Oh, that’s like truth or dare. Yes, I do.

Greg Dalton: True or false. You enjoyed it?

Adrienne Alvord: No.

Greg Dalton: Stan Glantz. True or false. Corporations have deeply infiltrated American universities and are influencing research output?

Stan Glantz: They’re getting there.

Greg Dalton: Adrienne Alvord. Oil industry lobbyists are charming and personal?

Adrienne Alvord: I know from personal experience this is true.

Greg Dalton: Steve Fainaru. True or false. You still love football and would let your son play when he was a teenager if he had asked?

Steve Fainaru: True.

Greg Dalton: Last question. Steve Fainaru. The NFL has peaked and will shrink significantly in your lifetime?

Steve Fainaru: I don’t know if I would say significantly. It will shrink for sure.

Greg Dalton: That ends our lightning round. Let’s give them a round of applause for getting through that.

[Applause]

We’re talking about football, oil and tobacco at Climate One at the Commonwealth Club. I'm Greg Dalton. We have Steve Fainaru, Stan Glantz and Adrienne Alvord. Steve Fainaru, I wanna pick up on that. When you were writing your book League of Denial, which in many ways really broke open the concussion crisis in the NFL, you had a teenage son. Did he want to play football?

Steve Fainaru: He was making noises about wanting to play football.

Greg Dalton: Teenage testing his dad.

Steve Fainaru: Sure, yeah. He was a freshman when Mark and I are researching the book.

Greg Dalton: Your brother Mark Fainaru-Wada.

Steve Fainaru: Yeah. And I, you know, I played high school football and, you know, it’s really a formative experience for me. I love football I continue to watch a lot of it. And where I finally came down was I still feel like in terms of what we know about the science that the actual risk of playing football like how many people actually get brain damage from playing football and how much of a risk it is, is not nearly established. We know that it’s dangerous it’s extremely dangerous at the college and the professional level. It’s not nearly as established in high school. And I guess I just didn’t want to be a parent who was sort of limiting experiences based on some unknown risk. That would certainly not be true of like smoking for example like it wouldn’t be like okay go ahead and smoke.

Greg Dalton: And now your son goes to Michigan. So talk about football at Michigan and concussion research at Michigan.

Steve Fainaru: Yeah, this is well timed because I just got back from Ann Arbor where I attended the Michigan-Ohio State game. And there were 112,000 people in attendance and it was really it was such an exciting spectacle. I mean I was really happy to be there in the student section with my son. And yet, you know, I know too much at this point and you know one of the things that is interesting about Michigan is there's a lot of really interesting concussion research that’s going on at the University. And yet when you're in the Big House as the stadium is known they play just videos constantly of these huge hits of people running into each other, hits that are certainly injurious and yet it's there for your entertainment. So it’s just this incredible disconnect between the University where significant concussion research is taking place. And the experience in this massive stadium and I think, you know, it kind of embodies where the country is at I think now we’re on that, you know. It’s hard to reconcile the two and yet, you know, we do it every weekend every Saturday and Sunday. Monday, Thursday, Saturday and Sunday.

Greg Dalton: Adrienne Alvord, do you think there's some anti-elitism and there’s a cultural piece to this about not trusting experts and kind of the public where this very populous moment politically. Tell us about your thoughts about that.

Adrienne Alvord: Well, you know, in American history we have a long tradition of sort of anti-intellectualism and I think that the way this relates to what's happening today is that there’s not only an anti-intellectualism, but there's a sense of rejection of experts. And this whole disinformation process that we’ve been talking about I think certainly plays into the cynicism that people have about fake news because they get a lot of information that turns out to be false. And, you know, there are duelling experts on television all the time and who do you believe? And so it inevitably becomes politicized. The information that you tend to believe tends to be the information that follows more your personal prejudices, your personal beliefs and those of people like you. So I think that that's been a really distractive thing for the discourse of this country and now we have frankly a president who can spout things on a regular basis that are patently false and apparently at least among his supporters. There's no real downside for that. That’s a very dangerous place to be.

Greg Dalton: Stan Glantz, we mentioned earlier that the tobacco companies innovated some of these things. You actually think that it was earlier than tobaccos. So tell us who really was and perhaps it was sugar that started it.

Stan Glantz: Well, yeah. I’m sure we got involved in the sugar issue too because it’s all the same stuff. And it turns out and the tobacco companies really got their whole disinformation campaign going in 1953. What had happened before that was the research on cancer was just coming together. There was an article in the Reader's Digest called Cancer by the Carton. And Reader's Digest at that point was the most widely read publication of the world, and this totally panicked the tobacco companies. And it was a good reason because it led to this huge outpouring of public concern there were calls for not only national legislation but states were talking about putting warning labels on cigarettes and banning advertising. So they got together at a very famous meeting at the Plaza Hotel which is actually in Merchants of Doubt too. And they came up with this idea of “doubt is our product.” And the way they did that are one of the key things they did was they found that is so-called independent research organization and one of the guys who applied for a job there have been working for the sugar industry and we have his letter applying for the job where he said look at all of the good sort of disinformation I've been spreading on sugar in the 1940s and why don’t you hire me. And they did, he was like the number two guy for the tobacco companies. And in both of these cases, in fact, in all of these cases we’re talking about, I don’t know about the NFL, but when you’re talking about global warming and the petrochemical industry or tobacco or sugar. One thing that really impresses me as we get into looking at these internal documents because these guys are really smart they know the science, they accept the science internally. They use it to make business decisions that the public positions they take are completely 180 degrees away from what they're doing. I mean with Exxon I mean, at the same time they were funding all this climate denialism they were saying, oh well we can do more drilling in the Arctic because the ice sheets are gonna melt. And the level of sophistication about their understanding of science and the level of sophistication on how to manipulate scientists is really impressive. And I think one thing that they've done a really good job of taking advantage of is the sort of innocence and naïveté of a lot of scientists who just can't believe people would be as evil as some of these guys are. And the result when you have these dueling voices and the media's propensity to always want to present two sides, even if there's not two sides, that really feeds into the public confusion and the public cynicism. And so there needs to be a little more judgment there when they say, you know, the science on this really is settled and we’re not gonna put Marc Morano on the television just because we can’t find a legitimate scientist to put on, which is what ends up happening.

Announcer: You're listening to a conversation about concussions, cigarettes, and climate -- narratives of deceit. This is Climate One. You can check out our podcast at our website: climate one dot org. Greg Dalton will be back with his guests in just a moment.

Announcer: You’re listening to Climate One. Greg Dalton is talking about football, tobacco, and fossil fuels with Adrienne Alvord, Western States Director at the Union of Concerned Scientists. Steve Fainaru, co-author of League of Denial: The NFL, Concussions and the Battle for Truth. And Stan Glantz, professor at the UC San Francisco medical school, and author of The Tobacco Wars.

Here’s Greg.

Greg Dalton: Adrienne Alvord, litigation was a turning point for the tobacco store there’s some litigation in New York and other places going after kind of what the oil companies knew and when. Tell us about that because that’s kind of potentially using some of the same tactics that led to the big $200 billion tobacco settlement.

Adrienne Alvord: Right. Well, the litigation that’s ongoing in New York is to me the most interesting because it really has to do with shareholder fraud. These are companies that are supposed to be disclosing to their shareholders business risks that they could encounter. And for a long time, most of the fossil fuel companies downplayed or just didn't mention the risks that climate change were posing to their products. The risk of course is that if it's found that fossil fuels are basically putting the planet at risk, there’s a risk that those fossil fuels could be regulated or even phase out as a result. And so now they're starting to be a little bit more savvy they're starting to talk a little bit about more about this, but they have really denied this for years. So it'll be interesting to see and I think one of the most important things that could happen for this is if there is discovery as there is, as there was with the tobacco industry --

Greg Dalton: That’s a legal process for bringing forth documents.

Adrienne Alvord: Right. It'll be very interesting if we can figure out what all they’ve been thinking all these years because the tobacco discovery process provided a treasure trove of information not only about what was going on in the tobacco industry and the fraud that was going on there but also with sugar and football apparently and other --

Stan Glantz: And global warming too.

Adrienne Alvord: -- and global warming.

Stan Glantz: I mean the big difference in what happened with tobacco because normally in these major cases where there's a lot of litigation, the plaintiffs get all this dirt from inside the defendant's companies and then when the case is settled, all of that is just destroyed. And the thing that happened in the tobacco litigation that was very unusual is the Attorney General of Minnesota Hubert Humphrey III who brought one of the first big cases said the most important thing to come out of this litigation is going to be the truth. And I'm not gonna settle this case, unless the documents that we got, the 25 million or so pages they got were made public. And that was the second to last thing it was settled the day the case went to the jury but he just said I'm not settling this case if those things aren’t produced. And so I've been saying for example to people who know the Attorney General in New York who’s bringing this big case, you know, are you gonna make a commitment not to settle that case without insisting that the, he’s already got a couple million pages I've heard, you know, I think it's very important for UCS and the other public interest groups to be pressuring him to make in which he has not yet done to make a commitment that all of that stuff will be made public. We would love to have it at UCSF we’ll put it on the Internet let people get it for free.

Greg Dalton: Adrienne Alvord, there still is no whistleblower the way Jeffrey Wigand was, you know, famously played by Russell Crowe in The Insider, a Hollywood film with Al Pacino. There's still no whistleblower or smoking gun, you know, aha that sort of doubt is our product moment for the oil companies or maybe there is and we just don't know about it.

Adrienne Alvord: Well I think that Exxon is really an example of kind of a tragedy because they were doing some of the best climate science research going in the 1970s and early 1980s. And they really wanted to do this they had business reasons for wanting to do it. They wanted to know, you know, how it impacts their businesses, their drilling and so on. But they also felt that if they were credible voices on climate science that they would be able to influence the process for good. But then around 1988 when James Hansen was telling the world that not only was climate change happening and being caused by fossil fuels, but it was potentially very dangerous and world leaders started to really think seriously about how are we going to control this. They defunded their legitimate scientific research and started funding disinformation in a major way. And it was this about-face that, you know, they could have been a force for good and they really chose to double down. And the thing is that date 1988 is important because in the course of the industrial revolution, you know, 200, 250 years we've burned, we’ve emitted a lot of carbon dioxide but half of it has been emitted into the atmosphere since 1988. Think of what could have happen if we’d started to change back in the 1980s.

Greg Dalton: We’re talking about cigarettes, oil and the NFL at Climate One at the Commonwealth Club. I'm Greg Dalton. My guests are Adrienne Alvord, from the Union of Concerned Scientists, Steve Fainaru, from ESPN and Stan Glantz from the San Francisco Medical School University of California San Francisco Medical School. Steve Fainaru, I wanna ask you about there’s a character in your book Kevin Guskiewicz, who was one of the original dissenters and then he flips and starts to sing the tune of the NFL. And one thing he says that there's still no cause-and-effect relationship. We still don't know exactly how a hit in a football game causes CTE which the same can be perhaps said of smoking. But tell us about Kevin Guskiewicz.

Steve Fainaru: Well Guskiewicz, he’s now a Dean at the University of North Carolina. He went there as a concussion researcher. He was a former assistant trainer of the Pittsburgh Steelers. He’s a huge football fan. And he was one of about a half dozen scientists who began to make connections between football and different forms of mental illness. In Guskiewicz’s case he had established pretty convincingly that the greater number of concussions that you incur on the football field, the greater the risk you have of depression later in life. And so that gained him a lot of notoriety and ultimately a MacArthur Foundation grant and kind of catapulted his career. And the NFL had attacked his research, this Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Committee had attacked his research and, you know, he had basically they had approached him and try to co-opt him. And then finally when the NFL disbanded that committee and reconfigured it they invited him on to basically to participate in the research. And he looked at it as an opportunity I think to really change the sport and they put him on the rules committee. And one of the first things he did was change the kickoff rule in football. And so it was moved up and so now the kickoff in football is the most dangerous play in football. It's basically a 22-car pile-up.

Greg Dalton: More distance, more speed.

Steve Fainaru: Exactly. And so Guskiewicz moved it up so there would be more touchbacks and there be fewer runbacks and fewer collisions. So that was the first thing he did but then suddenly he was making statements that were seem contrary even to his own research. And people began to call him on it and say, you know, wait a minute you’re now saying that there's really that science is being overstated and that there's hysteria and that we still really don't know the connection, the cause of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. And so now it’s almost like he's flipped and I think Mark and I have looked at him as the most fascinating case because we don't really understand it and it has to do with the psychology of this. And I was thinking about it actually what Stan was talking about sort of we don’t really understand that these people are really evil, you know, and I'm not sure, at least in the case of the NFL that I totally agree with it. I feel like there's a psychology that goes along with it that particularly in the NFL. The people look at that they’re the caretakers the custodians of this huge part of our culture which is football and that we don't want people getting ahead of it. We want to protect it and let’s not ignore all the great things that football does for us. And, you know, so soon they're like combating childhood obesity and, you know, the camaraderie and discipline that you develop in playing football and they turned into something completely different than what it actually is. And I feel like somewhere in there is Guskiewicz’s trajectory and honestly I would love to sit on a stage with him and try to figure it out because it's just a fascinating thing.

Greg Dalton: If you’re just joining us, we’re talking about football, tobacco and oil at Climate One from the Commonwealth Club. I'm Greg Dalton. We’re gonna go to audience questions. Welcome to Climate One.

Female Participant: Hi, I’m Layla Holzman I’m an energy program manager at As You Sow but I’m here as an individual. This question is mostly for Adrienne, curious to get your thoughts on the importance of going back and proving liability and instances of doubt mongering, given that a lot of those companies have since changed their tune and are currently more open and arguably doing more to address the issues now than they obviously were then and how important is it to, what are the trade-offs of going back and still focusing on what happened back then?

Adrienne Alvord: Well I think that it's clear that fossil fuel companies there's a lot of documentation that they misled the public about the danger of their products to the atmosphere. And as with tobacco I think it's important that companies are held accountable because who's going to be paying for it when we’re, you know, as we’re seeing now with increased storms and wildfires and hurricanes and all the rest of it, sea level rise of course. Who’s gonna be paying for that? We are. The public is gonna be paying for that. And I think that is important and we set as an organization the Union of Concerned Scientists has recommended that we start holding fossil fuel companies accountable for the damage that they have caused. Now there are issues of, you know, the First Amendment and freedom of speech the complicated legal issues terms of liability that we’re gonna be working out for several years. But the evidence of deception is there and I think that it's important that we establish this principle that when you basically defraud the public that you need to be held accountable.

Greg Dalton: Next question. Welcome to Climate One.

Male Participant: Hi, thank you. My name is Ryan Prescott. And my question is about we looked at tobacco, oil, football, is there also a precedent for this same playbook and this same deceitful strategies in marijuana legalization or illegalization with regard to pharmaceutical companies? This question is for all three of the guest speakers. I would love to hear your thoughts on this issue.

Greg Dalton: Stan Glantz, briefly, you're working on marijuana.

Stan Glantz: Yes. I mean I think what we’re witnessing now is the emergence of the new tobacco industry. I can do a whole three hours about that but I won’t.

Greg Dalton: Let’s go to our next question at Climate One. Thank you.

Male Participant: Thank you for your comments, Gary Malazian. You’re dealing with facts and figures the reason you’re not making headway at the speed that you would like to is because they have a better marketing campaign than you have. If you pick up your marketing, I think you’ll make a lot more progress. And sex and money make things happen in America. And what you're talking about is not sexy and not making a lot of money for big companies. So if you could market it a little differently than you’re marketing it, I think you'll make a lot more progress.

Greg Dalton: Adrienne Alvord, it’s true that scientists live with lots of facts and narratives change people's mind. We've done whole programs here at Climate One on facts don't change people's minds. Scientific community hasn't done a great job communicating this, fair point?

Adrienne Alvord: I think that is a fair point. You know, it's one of the dilemmas we face as a science-based organization you want to honor the nuances of science. It's complicated stuff that we’re talking about and we’re always trying to balance creating forceful message, but being really true to the science. And it’s a very, very difficult row to hoe. Scientists don't want to be sexy necessarily and most of them don't have very much money. So it's kind of foreign to the culture but we are very aware of the problem that communicating the hazards of climate change has been difficult. I think we’re getting better and frankly I think that people's personal experience of what's happening with the weather is starting to make them think wow, there may be something to this. But if you have suggestions and you are volunteering to help us, come see me after the show.

Greg Dalton: Let’s go to our last question at Climate One. Welcome.

Female Participant: Hi, Ellie Marks, California Brain Tumor Association. Thank you all for the work you're doing. This could've been called football, tobacco, oil and telecom. My colleagues and I have been fighting them for I’m almost into this for about a decade now wireless radiation is causing cancer. We have inconclusive evidence. You mentioned something like that before. What do we do? We are up against a trillion dollar industry at what point do we use the RICO Act, our hands are tied and we don’t know what to do and I’d like some advice.

Stan Glantz: Well this is an area I've actually been following. And see I have a cell phone, but it's turned off and I don't put it next to my head. And I think that the cell phone companies there's actually a literature out there on the cell phone companies and they’re playing all the same game. So if you look at who funds research on cell phones, you can predict whether it's gonna say there's a problem or not. And I think it's just the same. You need to like look at their website because it’s the same old playbook. And these fights whether you're talking about tobacco or climate and environmental things or dealing with football, it’s a matter of breaking through and just you know the politicians follow the public they don't lead. And it's just a tough fight.

Announcer: Greg Dalton has been talking about concussions, cigarettes, and climate with Adrienne Alvord, Western States Director at the Union of Concerned Scientists. Steve Fainaru, co-author of League of Denial: The NFL, Concussions and the Battle for Truth. And Stan Glantz, professor at the UC San Francisco medical school, and author of The Tobacco Wars.

To hear all our Climate One conversations, subscribe to our podcast at our website: climateone.org, where you’ll also find photos, video clips and more.

Please join us next time for another conversation about America’s energy, economy, and environment.

[Applause]

Greg Dalton: Climate One is a special project of The Commonwealth Club of California. Kelli Pennington directs our audience engagement. Carlos Manuel and Tyler Reed are the producers. The audio engineer is Mark Kirschner. Anny Celsi and Devon Strolovitch edit the show. I’m Greg Dalton, the Executive Producer and Host. The Commonwealth Club CEO is Dr. Gloria Duffy.

Climate One is presented in association with KQED Public Radio.