In Person at COP27: Funding the Global Energy Transition

Guests

Bogolo Joy Kenewendo

Alastair Marsh

Johnson Cerda

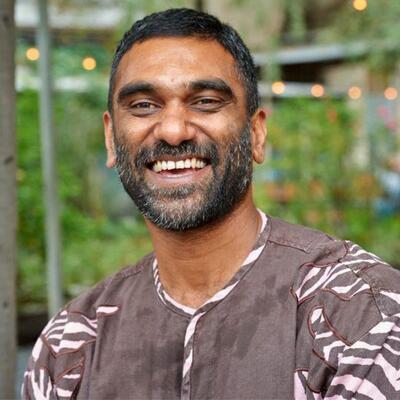

Arunabha Ghosh

Summary

Climate One has been at this year's UN climate summit, COP27, where one of the issues at the forefront of the conversation has been “loss and damage” – the idea that rich countries who have historically emitted the vast majority of climate-disrupting pollution should have to pay for the resulting suffering borne by those least responsible for the problem. At the same time, the whole world needs to drastically reduce its emissions and transition to clean energy – and that costs money, too.

When even wealthy countries struggle to meet self imposed goals to cut down on carbon pollution, how can developing countries, who are already suffering the effects of the climate crisis, fund their own moves to clean energy? Bogolo Joy Kenewendo, UN Climate Change High-Level Champions’ Special Advisor, Africa Director, says, “In order for us to really be able to build on a sustainable development livelihood we need to find different ways for those that have benefited in these emissions to compensate those that don't.”

Government payments from wealthy countries to developing nations are usually how compensation is thought of, but that doesn’t have to be the only option. Non-state actors, such as corporations or non-profit organizations, can play a significant role providing capital to developing countries to fund the clean energy transition. Kenwendo has long advocated for Africans developing their own capacity to address the crisis, and points to one industry that has already taken the lead:, “The insurance industry has recognized their role as risk managers and investors. And they have made their commitment to a $2 billion Africa climate risk facility that should be able to transfer loss and risk of $14 billion for the most vulnerable African populations through sustainable and market led insurance products.”

Net zero pledges have been a headline grabber for many companies and organizations – a way to signal awareness of the public’s increasing concern about the climate crisis. But how do we know that those pledges will actually have any real effect on reducing emissions?

The UN’s Independent High Level Expert Group on the Net Zero Commitments of Non-State Actors has released a report that aims to hold those companies and organizations making net-zero pledges to account. “We wanted to make sure that there are clear recommendations that are implementable by the non-state actors in order to separate the sincere and the committed,” says Arunabha Ghosh, CEO of the Council on Energy, Environment and Water, and member of the Independent High Level Expert Group on the Net Zero Commitments of Non-State Actors. The report also recommends that financial institutions immediately start phasing out investments in fossil fuel infrastructure.

Alistar Marsh, reporter at Bloomberg, lays out why regulation is needed to make net-zero pledges more than just a marketing tactic: “At the moment, this whole thing is voluntary, so it's easy to make the claim without any kind of punishment for not delivering.” At the climate summit COP27 in Egypt, there is talk of going from voluntary pledges to mandatory. Marsh continues, “If we’re actually gonna deliver on this thing, we need to put the incentives in place and the kind of enforcement structures to make it happen. Otherwise, it just becomes, it’s easy to greenwash.”

We often hear that indigenous people are stewards of much of the biodiversity, much of the land to be protected, and can offer millenia of experience to climate solutions. But that doesn’t mean that they are always included in climate conversations and negotiations. Johnson Cerda, an indigenous Kichwa of the Ecuadorian Amazon and a Senior Director at Conservation International, comments on his experience, “We came in ‘98 and 2000 as a group in order to say that we have something to offer, but the governments, they didn't open the door until 2007.”

When it comes to funding and implementation in indigenous communities to help mitigate the effects of the climate crisis, Cerda comments, “We have a lot of communities, why don't we start implementing and allocating the funding? And from the developed countries should come the funding.”

Related Links:

UN Panel Calls Out Greenwashers and Seeks Net Zero Regulation

UN Independent High Level Expert Group on the Net Zero Commitments of Non-State Actors Report

Full Transcript

Note: Transcripts are generated using a combination of automated software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the actual audio before quoting it.

Ariana Brocious: This is Climate One. I’m Ariana Brocious. At this year's UN climate summit, COP27, one of the issues at the forefront of the conversation is “loss and damage” – the idea that rich countries who have historically emitted the vast majority of climate-disrupting pollution should have to pay for the resulting suffering borne by those least responsible for the problem. At the same time, the whole world needs to drastically reduce its emissions and transition to clean energy – and that costs money, too.

Even Wealthy countries are struggling to meet self imposed goals to cut down on carbon pollution. How can developing countries, who are already suffering the effects of the climate crisis, fund their own move to clean energy? Climate One has been at the COP27 summit talking with climate leaders. Bogolo Joy Joy Kenewendo, UN Climate Change High-Level Champions’ Special Advisor, Africa Director, joined Greg Dalton to discuss how to rectify the great imbalances in money, power, and energy.

Greg Dalton: So, Africa's responsible for less than 4% of the planet’s greenhouse gas emissions. While the G20 is responsible for 80%. Yet people in poor countries are already suffering climate impacts first and worst. So, what impacts have you personally seen in Botswana?

Bogolo Joy Kenewendo: We have been experiencing quite shocking climate changes from extreme drought to the next year having floods that destroyed their legacy infrastructure we’ve been working really hard to have. And the droughts have caused hunger and instability in food security. It's not that we've gone back to you know a famine period but it is quite worrisome when you know there is insecurity in food production because that has ripple effects around inflation and the cost of living.

Greg Dalton: Do people tie that to climate change?

Bogolo Joy Kenewendo: You know for the most part, people do not tie changes. They will just say, oh, the weather has changed or the seasons have changed. And it is up to us to really reinforce the message that things don't just happen these are effects of climate change. You are literally experiencing the shocks due to the emissions around.

Greg Dalton: And then how do you feel about that being inflicted by countries and corporations and individuals like me, honestly far away?

Bogolo Joy Kenewendo: Well, you know, that has been such a strong conversation around with civil society and private sector in the continent. That if we've only contributed 4% of these emissions and we are the most vulnerable to shocks and the least capable to deal with adaptation and resilience, then we must be compensated for these shocks and the loss that we are experiencing as a result. And you recall that now for the first time we are talking about loss and damage here which essentially means we are losing so much of our infrastructure, our livelihoods because of these shocks that we didn't cause and we didn't even benefit from the emissions that have caused this shock. So, in order for us to really be able to build on a sustainable development livelihood we need to find different ways for those that have benefited in these emissions to compensate those that don't at least to build adaptation and resilience for the future.

Greg Dalton: When we have this conversation with Indigenous Americans in the United States who have erased and had all sorts of terrible things done to them. They don't like to be seen as victims. They want justice, but they don't want to be seen as perpetual victims. How do you thread that?

Bogolo Joy Kenewendo: I really like the way you are framing it because it’s a similar conversation here. It's not about oh, we are victims. We recognize we contributed less to emissions but we also see that there are a lot of opportunities in the space. But one thing that we have seen in particular this year is a lot of nonstate actors who are African coming up with solutions to the problem. And this week alone we had private sector from the continent committing to about three different initiatives. And if I may just take you through those. One is around the insurance sector recognizing that doing business in a climate vulnerable environment will make investors very skittish. So, the insurance industry has recognized their role as risk manages, risk carriers, and investors. And they have made their commitment $2 billion Africa climate risk facility that should be able to transfer loss and risk of $14 billion for the most vulnerable African populations through sustainable and market led insurance products. And cumulatively this should cover about 1.4 billion people or it translates to about 140 million people per year. So, these kinds of initiatives, they are showing that Africans recognize the challenge that we are facing an opposition in themselves with proper solutions. And then calling the world to and cooperate and contribute to the solutions that were coming with. Instead of just saying you know you cost this problem now pay us. But we are directing where that money should go because we know how these challenges should be dealt with. And I particularly really enjoyed those kinds of interventions. And another one is over 60 of Africa's biggest businesses African-owned biggest businesses, they made some serious commitment as well around they now call themselves the African Business Leaders Coalition. And they made some commitments. They released a strong statement saying that they are going to commit to key actions on meeting goals of the Paris Agreement and they will be supporting Africa's just transition towards a 1.5° future. And they are committing to building a thriving continent that is rooted in resilient green and competitive economy. And when you look at it, they are speaking to also investing in human capital, young people and ensuring that future generations are able to live in adaptive and resilient environment. And once again they are saying we are getting started; the world can join us.

Greg Dalton: That’s exciting because we know that governments don't have enough money and it's hard to get money out of governments. And this is the financial markets and private-sector stepping up. Here at COP 27 in Egypt, US climate envoy John Kerry announced a new platform for carbon credit trading calling it the energy transition accelerator. The ideas is that multinationals corporations will be able to offset their own emissions by paying for developing countries to develop renewable energy. What do you think of that plan?

Bogolo Joy Kenewendo: Yeah, I think you know when we heard Senator Kerry announced this it was right after we announced the Africa Carbon Market Initiative which was supported by President Ruto of Kenya and President Chakwera of Malawi and Bongo of Gabon. And we specifically started the African Carbon Market Initiative to value and commercialize the nature-based assets that we already have that are providing lungs to the world. And yet the communities there are not seeing the real value in monetary terms of protecting those nature assets. And so --

Greg Dalton: It’s not trickling down to the people who need–

Bogolo Joy Kenewendo: It’s not trickling down to the people. Or really at the moment carbon markets they do not value nature-based solutions the right way. The main issue with nature-based solutions and the voluntary carbon markets is that the pricing at the moment is somewhere between $5 and $10.

Greg Dalton: A ton.

Bogolo Joy Kenewendo: A ton. And we know that in mandatory markets in Europe in the US and in Asia, carbon pricing per ton can easily go for $100. So, we’re saying for the nature-based credits we should be getting value above $10 because it is more than just sequestration by forest. It is the biodiversity that keeps the ecosystem running. And that is something that pricing and valuing nature-based carbon credits should take into account. And what we’ve said in response to Senator Kerry and everybody is anyone who wants to partner in delivering in the mandate of ACMI can do so. And we particularly want the consideration of preferential pricing in the US for African nature-based carbon credits. But most importantly, we want the integrity piece around carbon markets to be prioritized. So, whoever wants to buy African carbon credits should recognize that them just trading in African carbon markets is not the final solution. They have to have other net-zero commitments. They must be working on reducing their emissions because just buying the credits isn't enough.

Greg Dalton: And so, you're saying that the carbon credits are underpriced. And I ‘ve been hearing a lot here in other situations where loans to African energy projects are charged higher interest rates. So, in some cases there is lower pricing on credits, higher pricing on interest loans to Africa. So, how is that affecting Africa's ability to deploy clean energy because the price of clean energy is going down, down, down but the access to capital and financing seems to be an obstacle for Africa.

Bogolo Joy Kenewendo: You know, it’s very interesting. Everyone keeps saying the price of clean energy is going down. That reduction hasn't necessarily been transferred into the continent. It is still quite expensive to venture into clean energy projects in the continent. And it’s because there’s still this perception risk premium that is associated with investing.

Greg Dalton: They don’t think they’re gonna get their money back.

Bogolo Joy Kenewendo: Yes. But we have evidence that shows that default rates for infrastructure financing in the continent is still in double digits while in other markets it’s double-digits.

Greg Dalton: So, what’s going on there, some kind of bias?

Bogolo Joy Kenewendo: So, it’s a bias that exists in the market. And I think it's because people haven't taken the time to learn and understand the African market. And this is one of the things that we are encouraging through we’ve been having regional forums to really sensitize investors on what it is like investing in the continent. What other financial instruments that have worked that derisk doing business in the continent. And what other partners are available in the continent that can help them really deploy capital better. And we’ve done that and we are now working on an Africa sector of GFANZ in order to --

Greg Dalton: The Global Financial Alliance for Net Zero.

Bogolo Joy Kenewendo: The Global Financial Alliance for Net Zero. For those members to connect with African financial industry and to have them communicate better. But what opportunities are what the real risk of investing in the continent, but most importantly, the opportunities that exist and how those can be tapped.

Greg Dalton: You’ve been a champion for Africa-led solutions. How should Africa go about developing local capacities so the jobs and profits from the energy transition remain in Africa?

Bogolo Joy Kenewendo: Well, I think first is about how the continent positions itself. Many African countries would position themselves. One is be very clear about what the projects are and how much the projects need in order to be able to channel the right kind of capital into those projects. So, that has been one. And then secondly, capacity building is a key issue. So, we are going to have to also invest in the development of human capital and understanding what building a green development pathway looks like. But most importantly build human capital that will recognize and position the continent to benefit more from this green financial infrastructure.

Greg Dalton: When I spoke with Wanjira Mathai, WRI's Africa director. She said most of Africa's trade is with Europe and Asia that only 15% of trade happens within African countries and African nations need to get better at trading with each other in order to build prosperity. As an economist and former minister of investment trade and industry of Botswana. How do you think Africa gets there?

Bogolo Joy Kenewendo: So, we have made good strides in terms of policy and negotiation around the Africa free trade continental area. And the good strides that have been made to enable the trade of goods started implementation during COVID, unfortunately. It was the 1st of January 2020. But two weeks ago, we managed once again to reach an agreement around the protocol on investment. Now, this one is one that is very important because trading of goods is easy. It is attracting and retaining investment that is a big issue. And reaching an agreement on the protocol of investment will create more credibility in investing in the continent. It will ensure that we are able to speak to the same kind of standards around investment in the continent and should be able to say to investors that you are protected when you invest alongside the AfCFTA.

Greg Dalton: One of your many roles has been as part of the G7 Gender Equality Advisory Council. How can empowering women help address the climate crisis?

Bogolo Joy Kenewendo: Well, you know, women are most affected and most vulnerable to our climate shocks. And they are disproportionately affected by climate shocks. So, when we invest or have gender lands investing towards women we are tackling directly issues of inequality of poverty and building adaptation and resilience. So, in order for us to really say we are dealing with gender issues or women issues, we must ensure that our recovery policies for one, speak directly and have KPIs that are gender --

Greg Dalton: Key Progress Indicators.

Bogolo Joy Kenewendo: Yes. Key Progress Indicators that are directly linked to success or progress around women. And we believe that particularly for adaptation and resilience if we are looking at access to water, we're looking at access to markets, building roads that provide access to markets. We will create an enabling environment for women to be active participants in the economy, not just active but very efficient participants in the economy.

Greg Dalton: Thank you very much for coming on Climate One. It’s an honor to talk with you today.

Bogolo Joy Kenewendo: Thank you very much. It's been my pleasure.

Ariana Brocious: This is Climate One. I’m Ariana Brocious. Net zero pledges have been a headline grabber for many companies and organizations – a way to signal awareness of the public’s increasing concern about the climate crisis. But how do we know that those pledges will actually have any real effect on reducing emissions?

Arunabha Ghosh is CEO of the Council on Energy, Environment and Water. He is a member of a UN task force focused on this question and spoke with Climate One host Greg Dalton about their recent report.

Arunabha Ghosh: This report is by the independent high level expert group on the net zero commitments of non-state actors, uh, set up by the UN Secretary General on the 1st of April. We were given a very clear task to think about the principles and the recommendations that avoid greenwashing by corporations or by cities and regions that are committing to net zero but not always delivering. And we wanted to make sure that the, the, there are clear recommendations that are implementable by the non-state actors in order to separate the sincere and the committed, uh, from those who are merely making statements or grabbing headlines. In this recommend, In this report, we have clear recommendations demanding that non-state actors not only outline a target of net zero, but clear pathway to get there with interim targets, which can be held to account, which can be independently verified and monitored, and that they make sure that their reductions in their emissions happen by their own actions rather than buying up low quality cheap credits elsewhere. At the same time, we strongly nudge the non-state actors to look at using high quality credits to invest in the developing world, to look at investment opportunities in the global south, where the sustainable infrastructure is needed, where people are most vulnerable to changing climate, and where the cost of finance is significantly higher than in, in the rich world. So if we can combine these two strands, then we actually are able to demonstrate that a net zero commitment translates into action and translates into just outcomes for the majority of the world's people.

Greg Dalton: A fellow member of this commission just said to me that the Secretary General is furious that the banks are pledging to large banks are saying, We're gonna go net zero while they're still sending massive amounts of loans in capital to further extraction of fossil fuels. Is that right?

Arunabha Ghosh: We have made a very clear recommendation in the report that financial institutions have to immediately start phasing down from, from removing their investments from fossil fuel infrastructure. And then we have a differentiation for when they're able to extract that out of, uh, from OECD countries, which is by 2030 and by 2040 for non OECD countries. But there has to be a clear pathway towards ending financing. Uh, fossil fuel infrastructure and, and extract new extraction activities, um, which then locks us in into a much more unsustainable pathway for the decades ahead.

Greg Dalton: But these banks answer to their shareholders. They don't typically listen to the UN for how to run their business. How do you think they will listen?

Arunabha Ghosh: You know, because climate, climate risk is now facing us. Uh, for the longest time we resumed that the poor will adapt and the rich will escape. But if 2022 serves any lesson, it is that extreme heat, extreme weather events is impacting us all. And therefore, financial institutions must also have a fiduciary responsibility to the integrity of the assets in which they're in investing.

Greg Dalton: Sounds like you're after the social license to operate.

Arunabha Ghosh: It is not just the social license to operate. It is also the, the risk of financially stranded assets. If they are continuing to invest in fossil fuel infrastructure and infrastructure that is unsustainable or that does not take into account climate risks or that they don't declare, um, the, their exposure to, to climate impacted assets, then they're not actually fulfilling their responsibilities to their shareholders.They're not actually preserving shareholder.

Greg Dalton: Last question is, it was interesting to note that you called for full disclosure of lobbying because companies oftentimes tell us one thing on TV ads, and then another thing happens in the corridors of power. So how important is that gonna be? What are you trying to do there to get more, um, what are you trying to accomplish by calling for a disclosure of lobbying?

Arunabha Ghosh: I think it's very important to recognize that if you're gonna say something, then you actually mean it, um, and that you don't say something in public and in private you lobby for something which is the polar opposite. And this is why we are, uh, we are arguing that if you are voluntarily declaring a net zero target as a nonstate actor, then you have to also adhere to the highest principles of highest environmental integrity. Of course, in your respective jurisdictions, there might be regulatory reasons why you have to declare a net zero target. And those regulatory, uh, directives will be determined by the governments, but you cannot voluntarily declare net zero and then lobby those same governments in the jurisdictions where you're operating for slightly lax regulations or to carry on, you know, uh, with business as usual. Either do what you say or don't say it at all.

Greg Dalton: Doctor, thank you for your time.

Arunabha Ghosh: Thank you very much.

Ariana Brocious: Arunabha Ghosh is CEO of the Council on Energy, Environment and Water. To continue this conversation related to net zero pledges made by non-state actors, Greg Dalton met up with Alastair Marsh, a reporter at Bloomberg.

Greg Dalton: Hundreds of companies have jumped on the net-zero bandwagon with all kinds of goals and pledges and promises. Yesterday we heard the secretary general say, “using bogus net-zero pledges to cover up massive fossil fuel expansion is reprehensible. It's rank deception. The toxic cover-up could push our world over the climate cliff.” What did you think when you heard the secretary general say those words?

Alastair Marsh: Well, he has a very some very eloquent lines; he was quoting, well, I’m not sure if he’s quoting directly AC/DC. But he did say that we are on a highway to hell which made me smile in a dark kind of way because I like that song. But he’s right I mean net-zero has become a, I mean on one hand it’s a simple idea that you eliminate your emissions as much as you can. And then you'll offset the residual or you do something with the residual. But it’s become a sort of if you’ll excuse the phrase bandwagon that everyone's jumped on without really thinking through what it means or without really wanting to explain it. You just think about the consequences for their operations or their relationships with their customers and should they even have some of those relationships if they deliver on those targets. And so, it becomes easy to say, hard to deliver on. I guess with all, everything that’s discussed at COP is easy to say, hard to deliver on. But this is sort of a corporate world, well, actually there have been some governments who have made net-zero commitments too but it’s been really adopted by corporates. And there’s a lot of, well, I wish to use the word greenwash if you’d allow me, but let’s just call it hot air or unsubstantiated claims. Things are again, easy to say, hard to deliver.

Greg Dalton: Right. And a few years ago, very few companies had net-zero pledges and now even Exxon Mobil has a net-zero pledge. It seems like it’s become this sort of fad. There's a new UN report out, released here at this COP 27. It lays out a 10-point plan to end greenwashing or let’s use that term. It includes companies issuing public plans, setting interim targets. Yearly public reporting on their progress and disclosure of lobbying activities. What impact do you think all this will have on corporate net-zero pledges?

Alastair Marsh: Well, to answer that in most direct way it depends if it gets regulated or not. Like at the moment this whole thing is voluntary. So, it's easy to make the claim without any kind of punishment for not delivering upon it.

Greg Dalton: Right. It’s a lot of, hence the greenwashing like companies because it’s not really regulated and usually corporate America doesn't take instructions from the UN.

Alastair Marsh: Right. at COP it seems like there are lots of themes that get spoken about in all kinds of corners. But whether like actually it gets latched on and developed and delivered upon is another thing. But one of the themes I hear a lot of head so far is around from voluntary to mandatory certainly on kind of on the delivery of net-zero. If we actually gonna deliver on this thing we need to put the incentives in place and the kind of enforcement structures to make it happen. Otherwise, it just becomes, it’s easy to greenwash it’s just too easy to greenwash. So, yeah, the Catherine McKenna's report was all about delivery.

Greg Dalton: We’ll just say she is the former environment minister in Canada former member of Parliament in Canada who chaired this report. It included a bunch of regulators and former regulators from around the world and they’re saying this is what should happen.

Alastair Marsh: Exactly. And I was going to say that the point there about interim targets is important. So, doesn’t matter making it mandatory in some way, but also the interim bit. Because the order of the net-zero targets is 2050 when most current management will be long, long retired. It’s just too far in the future to be realistic or to be tangible let’s put it that way. So, if you have a 2025 target or a 2030 target well, that’s something that you can think about okay, the next three years, what do I need to do what would it be like to get my business on a path aligned with Paris? And of course, this is supposed to be the decade of delivery., the decade of action as they call it. Where we’re supposed to call into the sides reduce emissions by half. So, to get on the path to net-zero cut emissions by half by 2030 and then the rest in the next 20 years. So, we should be seeing a lot more, we could be a lot more aggressive now, let’s put it that way.

Greg Dalton: just the kind of basic things that are taught in business school, right, is to have kind of key progress indicators. Why shouldn't corporations run their carbon commitments the way they run making serial and making widgets and everything else, right?

Alastair Marsh: Yeah, and the report also goes off to some of the more kind of nefarious stuff like funding, you know, funding kind of anti-climate lobby groups so that kind of, or that your lobbying should be aligned with your climate goals and not to be on the one hand saying, yes, we agree but on the other hand actually lobbying for the things that are, you know, contrary to that. Another thing that's interesting in the report that goes back to motivation and how you kind of incentivize or force people to do what's needed on net-zero is that they recommend that net-zero targets focus on absolute emissions reductions, not carbon intensity.

Greg Dalton: Carbon intensity being carbon per unit of output.

Alastair Marsh: Yes. Which climate activists have pointed out that your carbon intensity target can actually look good but at the same time you can hit that target and also increase fossil fuel production or usage of fossil fuel or financing the fossil fuels in the case of investors. So, that's another slightly niche point but it all comes back to the point of we need to kind of get rid of all the excuses and the loopholes in the system essentially.

Greg Dalton: Right. They’re very clever at finding those. About 80% of the global economy is now under the goal of net-zero emissions. This group of high-level experts convened by the UN says it's now time to focus on the quality and implementation plans. So, how do you personally, this is your beat for Bloomberg. How do you personally look at these net-zero plans and what kind of personal sniff test do you have or how do you judge yourself?

Alastair Marsh: Well, I guess the first obvious sniff is who is this company and what do I know about them already. I mean let’s take big oil, we’ve seen several oil majors make net-zero commitments. Well, that smells bad just on the face of it. I mean, some would argue that they have in some ways the technical resources they have the balance sheet to kind of deliver on ambitious decarbonization. Yet at the same time it kind of runs against their economic modus operandi and just the general kind of way of being for the last 80 years or however long. That doesn't mean that they can't do it, but it requires extra degree of scrutiny and sort of skepticism.

Greg Dalton: Right. Because there’s not trust in the brand and the story.

Alastair Marsh: Yes. And the same rings true in finance, which is where I actually spend more of my time looking at banks asset manages pension funds and then net-zero commitments. And they are in some ways, one step removed from the real economy. In that they are a kind of Mark Carney who we’ll talk about later and I can explain who he is, a big name in climate finance, likes to say that finance is an enabler, a catalyst is not in itself responsible in some ways for emissions, it just enables emission.

Greg Dalton: They’re funding the oil wealth they’re not drilling the oil.

Alastair Marsh: Right. Exactly. But even in my coverage of that space you can tell quite easily like which banks are the most serious and which banks are not for example, based on the kind of the statements of the CEOs. The kind of the seniority of their sustainability people. The credibility and detail of their targets around climate.

Greg Dalton: So, who’s on Alastair's list of the good list and naughty list?

Alastair Marsh: Well, I probably shouldn’t name names or I’ll get in trouble but I might give a geographic breakdown. By which I simply mean and this is easy for me to say is a Brit. But the Americans and the Canadians would be on by naughty list, generally speaking, if I could say that. But that might be just simply a function of, this all boils down to fossil fuel finance. and the historic relationships that have been built up with big oil basically, or with the big polluters.

Greg Dalton: Well, certainly JPMorgan Chase is known to loan hundreds of billions of dollars–

Alastair Marsh: Wells Fargo, Bank of America, Citigroup.

Greg Dalton: --to fossil fuel interest since Paris. And that’s I think what the secretary general was calling out these banks saying, we’re gonna be green oh, and we’re gonna continue to loan billions of dollars to extracting more fossil fuels which the International Energy Agency says we don't need more fossil fuel extraction.

Alastair Marsh: Now, the kind of counterargument to that is that we do that even in the IEA's net-zero by 2050 scenario there is still fossil fuels. It’s not like they disappear altogether it's just that we would only need money to kind of, not stop new extraction is to maintain existing facility --

Greg Dalton: Not searching for new stuff to dig out of the ground. There’s enough on the balance sheet already to fry us all.

Alastair Marsh: Exactly. And on the flipside, we should be massively ramping up investment and finance to renewables.

Greg Dalton: So, the banks are trying to kind of what I heard of this UN push was trying to the banks are trying to kind of have it both ways. Keep lending to fossil fuels get green cred for their consumers and probably their employees. And the UN is coming in here saying, whoa, whoa, whoa. We see kind of a shell game going on here and they’re trying to pressure the banks.

Alastair Marsh: Yeah, it’s have your cake and eat it. I mean, there’s a lot of money to be made in the energy transition and in financing green things. It’s interesting that JP Morgan at least the most recent data I've seen they've both been, you know, since Paris as you said they are the biggest financer of fossil fuels, but they’re also in the last few years they've been either number one or near the top of the underwriters for green bonds. So, they see sort of you know they’re in the money business, and there's money in oil but there’s also now money in renewables. And I guess it then becomes, what are the incentives and how can they be pushed to flip all their emphasis and as much as sort of scientifically proven or in line with what science suggests around climate to the greenside.

Greg Dalton: you’ve written that many corporations are so afraid of being called out for greenwashing they’re now keeping their emission reduction plan secret. The phenomenon called green-hushing which I’ve never heard of before I read your article. What impact is that having on corporate pledges? I talked to some corporate people who have some sympathy for who think whatever we do is never gonna be good enough. Because there’s always gonna be some enviro out there banging on us to do more.

Alastair Marsh: I have some sympathy for that perspective. Just a few years ago banks, asset managers, big investment firms were almost not considered really by climate activists. They were protesting outside Exxon and things like this. But there is no one outside JP Morgan's office or BlackRock for example. But actually, that's really changed in the last couple of years because people have realized more and more that banks are this so-called money pipeline behind the oil pipeline, i.e. there would be no oil pipeline without the money that comes from JP Morgan or Wells Fargo or HSBC or any of these banks. you’ve seen it in recent times pressure on Larry Fink, you had protesters trailing him for a period. You've had in London you've had Extinction Rebellion smashing windows. At JP Morgan and HSBC, you've seen green paint thrown all over Lloyd's of London the insurer to symbolize that they are greenwashing. And so, in that environment and in that climate, yes, there’s going to be a reticence to publicly say it's going to overpromise and under deliver, which is what you’ve had in the past. It was easy previously to just kind of come out there without anyone really criticizing you the tables have really turned right now.

Greg Dalton: So, speaking of capitalists, I'm curious, you know, you work for one of the most successful visible capitalists. And yet, do you ever yourself have doubts about capitalism solving this? they’re playing the game by the rules and maybe they've written the rules. But do you ever have personal doubts about where capitalism itself that were kind of all this stuff is kind of rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic?

Alastair Marsh: I do, yeah. I mean I’ve been on the sustainable investing climate team at Bloomberg for three or so years now. I think over that time I’ve become increasingly cynical. I mean maybe I'm just becoming a grumpy old man, possibly. But it just seems like the more you speak with people in finance, now, there are some very good committed people in the finance industry who care deeply about this issue and are working hard on them. But there are also a lot of people who really yes, they acknowledge climate change is real. Yes, it may affect future generations. Yes, maybe it's happening a little bit now but let’s not talk about that. But they’re not really like it hasn’t clicked in their head that their day-to-day activity is exacerbating it making it worse or if it has it hasn't bothered them enough to do something about it. And so, this were the capitalist impulse to kind of money, money, money money, well, certainly doesn't work for everyone. As we’re talking about here in this COP where, you know, Egypt, Africa, the emerging economies are gonna pay much heavier toll. So, there’s that aspect. But even for those who are self-interested Western financers in the long run, you know, the money train from fossil fuels is going to dry out and the kind of the physical impacts of climate change are gonna be economically speaking, let alone humanly speaking, incredibly damaging.

Greg Dalton: So, you kind of outline the people who dismiss climate change. I worry more also about people who are sincere in the sustainability field but aren't courageous enough to ask themselves and others the real systemic deep questions. Like are we fooling ourselves that this system, you know, we’re in a car going toward a cliff and we’re trying to tighten a few bolts inside the car. But the car is still going toward the cliff and we don't really want to – we kind of know the cliff is there, but we do want to admit it to ourselves that it’s there.

Alastair Marsh: Yeah. Well, I think the people that care most deeply about sustainability and climate within banks or investment houses are usually not in charge. As in, I think a lot of CEOs have come to understand that it's in, you know, that is something that they need to be cognizant of and that climate change will have impacts on their business. But I think those who care most deeply about it and would love to kind of re-orientate or, you know, restructure the way the thing operates so as to be more in line with the kind of the science are usually not in the positions of power which I think is problematic in some ways.

Greg Dalton: Well, thank you Alastair for sharing your sights. Alastair Marsh is a reporter from Bloomberg. Thank you very much.

Alastair Marsh: Thank you.

Ariana Brocious: This is Climate One. I’m Ariana Brocious. Johnson Cerda is an indigenous Kichwa of the Ecuadorian Amazon and a Senior Director at Conservation International. He joined Greg Dalton for a conversation at COP 27.

Greg Dalton: We often hear that indigenous people are stewards of much of the biodiversity, much of the land to be protected, are really significant players and can offer a lot for climate solutions.But does that translate to being recognized and heard when it comes to a big event like this?

Johnson Cerda: Well, it hasn't been easy because we came in 98 and 2000 as a group in order to say that we have something to contribute. But the governments, they didn't open the door until 2007 when they included the first wording in terms of indigenous people's participation. I just came from a this morning where we, we had to say that we are here, we wanna contribute and we have knowledge. And I see that. We have opportunities. It's sometimes it's becoming very technical and, and we need to also elevate our capacity as, as indigenous peoples in terms to document the information and bring evidence because we have, we are orals and we have information. We have, as I said, knowledge, but we need to also bring some data for, for the discussion.

Greg Dalton: So what I think I heard there is gradual progress being listened to more, but still indigenous countries. For example, in the United States, Navajo Nation and other dig groups, when they deal with the federal government, it's sovereign to sovereign, right? But here, under the United Nations, Navajo Nation doesn't have standing. It's not a, it's not a member state, so to speak. So they're under the US delegation. That's true for all the other indigenous people, they're under the nation state. So does that put them in the shadows?

Johnson Cerda: Well, Yeah, that is, that is an, uh, a concern that we have because at the United Nations, uh, level, what we are trying to get is perhaps the, we call it enhanced participation of indigenous peoples. Actually, a dialogue is happening around that because, as you said, there are countries where indigenous peoples, they have treaties with the government. But most of the countries, at least in developing countries where I come from in Ecuador, we are under the, you know, the, the shadow, as you said of the governments. And that is something difficult because what we wanted to have here in this convention is to have a dialogue perhaps at the same level. That's our goal. That's our goal because we said that we can contribute. That's why we wanna have a conversation at the same level, but. there's opposition for that. because, still discrimination is, is there. But we have countries where we are recognized but not given opportunities to contribute mainly. But also there are cases where, you know, we have countries with good legislations of indigenous peoples, but, but still the governments are affecting our rights, our land, our territories. So at, at this level, let's say at the beginning in that negotiation, we've been refusing to be part of the government allegations, to be honest, because we thought that they are like our enemies because they are making decisions against our interests as indigenous peoples so we've been refusing for a long time, but I see lately that we are part of the government, they being a bit open in terms of coming here, For instance, myself in the delegation of e. you know, and many other colleagues in several delegation, even from Canada, I see some indigenous colleagues in the US delegation. We are perhaps being part of that and, and trying, uh, trying to open the door and put our ideas in their own statements before they, you know, present here in the negotiation. So we feel like it's been changing a bit. And it takes time. It takes time for us. It's been long journey. I am saying that we started in 2000, it is 23 years that we've been saying to the government is that we, we could also contribute. We are here to, to help for climate action. And, and I see a bit, you know, doors open, but it's not enough.

Greg Dalton: So gradual recognition over, over time, indigenous people manage much of the forest land around the world. What do you see as an effective way to support their efforts to preserve those ancestral lands that are very important for sequestering carbon and for people who live far away?

Johnson Cerda: Yeah. For us, it's not only to sequester the carbon, it's our, it's our life. Cultural, our, Yeah. It's the way we are living using the forest because we, we've been living for long time like that. But it happens that now it's important, the carbon for

Greg Dalton: White people suddenly care about it because it matters to them.

Johnson Cerda: Exactly. And, and now, you know, sometimes the government, they wanna teach us how to protect the forest. We said, we've been protected for a long time and, and we should come to learn from us. And yeah, it's important. But I think the lesson learned in the experience I have with a dedicated grant mechanism for indigenous peoples and local communities. Uh, you know, the idea is to have for indigenous peoples direct access to the fund, to the climate funds. So having this fund, for instance, let me put just an example in Peru, um, in order to get a land title in Peru. It, it used to take for about 15, 20, sometimes 30 years because of the bureaucratic process in the government. Even having funding, sometimes the government, they don't reach there after, you know, that, that many years, 20 years, but now have been funding directly in, in the case of Peru in one year, and perhaps the latest one, I mean, the longest one is like two. They're having the, their land title because they have received directly the funding and they are inviting the governments to come to the communities to make the reports that they need to make. And then in two years, they're having their, their land title. So that means the participation of indigenous peoples and if they have access to the resources, they can also, you know, secure the land and continue contributing with the conservation of forests as a carbon stock. Right. For, for, for the interest of everybody. So I think it's important that we need to recognize that indigenous peoples need to receive the funding directly in order to continue contributing.

Greg Dalton: And where do you think that funding can come from? What are the sources of that funding?

Johnson Cerda: Well, in, in general, you know, the commitment that's the governments have like the a hundred billion dollars that they have to contribute for developing countries. That's one. But as everybody is saying, also in the convention, uh, they should, uh, bring additional funding for, for climate action, and not just from this funding that they have for developing countries already set up for some time. So new funding we don't see is coming. You know, the commitment, the governments made in 2009, about a hundred billion starting in 2020 per year. We don't see that is happening. We are in 2022 and the year we don't see that happening. And that's why I agree with the, you know, government saying that this COP needs to be for implementation. We have a lot of communities, why don't we start implementing and allocating the funding? And from the developed countries should come the funding. And also we are exploring the, you know, the resources from the private sector.

Greg Dalton: What's your personal journey here on Climate One? We'd like to connect the systems and the individuals. You've told us a little bit, but what's been your personal journey, um, as a climate advocate?

Johnson Cerda: Well, um, first of all, since I come an indigenous community in the Amazon, um, I have, well, my life was in the community or I was in my house in charge of, uh, going for fishing and you know, the food for the family, that was part of my work given since I was like six years old or seven years old. I had to do that for the family. So I, I am very closely related with, with nature in general. Indigenous, we are very connected with nature, but I was deeply connected because I used to go, you know, every day birds, every day, the wildlife. Every day bringing some fish. Uh, so I, I'm really connected with that and what I see is that climate change is impacting that kind of life that we, we had in the community.and also I see that, uh, for instance, because of climate change, um, parts of the forest are getting dry. And we see that clearly in the wildlife. For instance, monkeys, uh, the wild, wild boars or any kind of animals, they go close to where they can find, uh, water. And sometimes now it's easier to hunt them because they are not deep in the forest. They are close where they find the water. So the hunters they know now is very easy. And when it is too dry. It's easy to identify when the animal is coming in the rainforest because, you know, it's, it is, the forest is you, You can see too, so far, but you can hear that they are coming because of the, the, the, the leaves in the ground and they are dry and easy for them to hunt. And so things are changing.

Greg Dalton: So, it's one thing to notice changes, it's another to gain confidence as a fisherman and an indigenous community to speak up. So is what's driving you? Is it, is it, is it fear about what you're gonna lo lose? Is it excitement about what you can share? Is it anger at what's happening?

Johnson Cerda: Well, yeah. Uh, anger in one side because it's affecting too much in some regions. Um, but also, um, thinking in the opportunities that we could have in order to, to share. Here in the negotiations of climate negotiations, many times they open opportunities to contribute, For instance, in adaptation on, on mitigation, but we don't have resources to do our own research. And we don't see people giving resources to make research and come up with some evidence here. And, and we do what, what we can in order to contribute, but we are still expecting that. So we use all of this in order to say that, um, you know, in order to provide capacity building for our, our colleagues coming to participate here, perhaps colleagues that are mostly affected by climate change because we have areas where they are mostly affected.

Greg Dalton: So what's it like? We're sitting here at this conference with thousands of people from all over the world with all sorts of languages and dress, et cetera, many indigenous people. What's it like for you being here right now?

Johnson Cerda: Well, uh, for me it's a bit perhaps easier because I have experience here in, you know, many years of experience. At least can speak English and it's easy to communicate. But we have most of the delegations with just one language. we have people from, you know, communities, perhaps they don't speak very well, even Spanish and being here in this space is unfair for them. So what we do is also we use resources in order to provide interpretation for them to make fair participation for them. And listen, what's going on here? Yeah, it is challenging, but also opportunity to network with, uh, different institutions here and, and companies, uh, in order to share our concerns that. And, and yeah. You know, work with also governments. I, I, I've been participating in a couple events here, uh, with some governments and we express our concerns that we have, uh, in terms of, um, participation, funding needs, human rights issues, land tenure, you're, you know, importance for communities. So sharing our concern.

Greg Dalton: Well, thank you very much, Johnson for sharing your thoughts with us on being here at, Cop 27 in Egypt. Thank you.

Johnson Cerda: Thank you very much.

Greg Dalton: This wraps up our on the ground COP27 coverage as our team returns to the U.S. If you missed last week’s COP episode on loss and damage, find it and all our episodes on our podcast feed. Climate One’s empowering conversations connect all aspects of the climate emergency. To hear more, subscribe wherever you get your pods.

Talking about climate can be hard-- AND it’s critical to address the transitions we need to make in all parts of society. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review if you are listening on Apple. You can do it right now on your device. You can also help by sending a link to this episode to a friend. By sharing you can help people have their own deeper climate conversations.

Greg Dalton is Climate One’s host and executive producer. Brad Marshland is our senior producer; Our managing director is Jenny Park. Our producers and audio editors Austin Colón and me, Ariana Brocious. Megan Biscieglia is our production manager. Our team also includes consulting producer Sara-Katherine Coxon. Our theme music was composed by George Young (and arranged by Matt Willcox). Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. Thanks for listening.