Me vs We: What Matters Most for Climate Action?

Guests

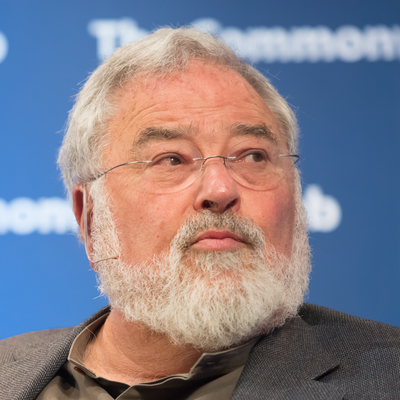

George Lakoff

Amanda Ravenhill

Margaret Klein Salamon

Summary

This program was recorded at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco on February 26, 2020, just before coronavirus was declared a global pandemic and overturned our daily lives. As that drama started to unfold with frightening speed, Americans were encouraged to take individual action for societal benefit – echoing the calls for everyone to cut down on carbon emissions because of a societal benefit larger than ourselves.

One person practicing social distancing may not seem to have an impact on the spread of coronavirus, but when thousands of people do it there is a real and measurable reduction in transmission rates. The climate challenge, on the other hand, won’t be solved by individuals focusing only on their own carbon footprints.

“An alternative would be what’s your carbon handprint,” suggests Amanda Ravenhill, Executive Director of the Buckminster Fuller Institute and a co-founder of Project Drawdown. “What are you able to do that other people aren't able to do that's going to be proactive, that you’re creating more good in the world.”

What’s needed, of course, is collective action. But what does that really mean? According to UC Berkeley cognitive scientist George Lakoff, being part of a community and knowing that’s community institutions and values is key.

“What are the institutions involved and how can an individual connect to various institutions in a system to have some effect,” he says, “and to know other individuals who can they can join with to have a greater effect.”

In other words, taking individual action means more than simply purifying our habits within a system that encourages over-consumption. Margaret Klein Salamon, Founder and Executive Director of the Climate Mobilization, believes that what individuals can do is show their peers how they might transform our broken system.

“if we’re responsible for solving this then the idea of competition between organizations or organizers – forget it,” she says. “What we need is to build power until we can create unbearable pressure for our politicians and institutional leaders and turn this ship around radically and as soon as possible.”

Additional interview:

Jonah Gottlieb, student and director of Schools for Climate Action

Related Links:

Buckminster Fuller Institute

Center for the Neural Mind and Society

The Climate Mobilization

Project Drawdown

Schools for Climate Action

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One, leading the conversation about energy, the economy, and the environment. [pause] Climate change won’t be solved by individuals focusing only on their own carbon footprints.

Amanda Ravenhill: An alternative would be what’s your carbon handprint -- what are you able to do that other people aren't able to do that you’re creating more good in the world.

Greg Dalton: What’s needed is collective action. But what does that really mean?

George Lakoff: It’s being part of a community knowing community institutions and the values of those institutions and what they do.

Greg Dalton: If not us, then who? If not now, when?

Margaret Klein Salamon: What we need is to build power until we can create unbearable pressure for our politicians and institutional leaders and turn this ship around as soon as possible.

Greg Dalton: What Really Matters for Climate Action. Up next on Climate One.

---

Greg Dalton: I’m Greg Dalton. Today’s episode was recorded with a live audience in late February. That was before coronavirus was declared a global pandemic and overturned our daily lives. As that drama started to unfold with frightening speed, Americans were encouraged to take individual action for societal benefit. Young and healthy people were asked to stay away from bars, sporting events and other gathering places because of the risk everyday social behaviors pose to the vulnerable people around us. As someone who thinks about climate all day everyday, this echoes the calls for everyone to cut down on carbon emissions because of a societal benefit larger than ourselves.

One person practicing social distancing may not seem to have an impact on the spread of coronavirus, but when thousands of people do it there is a real and measurable reduction in transmission rates. When it comes to climate, people also claim that voluntarily reducing your own footprint is one way for individuals to feel like they are taking meaningful action.

Margaret Klein Salamon: What you're calling individual action I think I might call consumption purification.

Greg Dalton: Margaret Klein Salamon is a former clinical psychologist, and founder and Executive Director of the Climate Mobilization, a volunteer powered organization that seeks to rapidly transform our economy to protect humanity and the living world. She’s also the author of the new book, Facing the Climate Emergency: How to Transform Yourself with Climate Truth. She believes that individual action means more than just behaving virtuously inside a broken system.

Amanda Ravenhill: Your money is not just sitting in the vaults of your bank and your credit cards, it's being leveraged over and over again for the economy that we don't want.

Greg Dalton: Amanda Ravenhill is Executive Director of the Buckminster Fuller Institute, and co-founder of Project Drawdown, a comprehensive plan to reverse global warming. She's also an advisor to the Center for Carbon Removal, and a fervent believer in the importance of relationships for getting people to act.

George Lakoff: How can an individual connect to various institutions in a system to have some effect. And to know other individuals who can they can join with to have a greater effect.

Greg Dalton: George Lakoff is Professor Emeritus of Cognitive Science and Linguistics at the University of California Berkeley, and Director of the Center for the Neural Mind and Society. His many books include Metaphors We Live By, Moral Politics and Don't Think of An Elephant. Our conversation about individual versus collective action began with Margaret Klein Salomon describing how her career as a psychotherapist was interrupted by a climate epiphany.

Margaret Klein Salamon: I use the defense of willful ignorance for much of my adult life. I knew enough about climate that I avoided it as much as possible. But as I grew up a bit and matured and living in New York City through Hurricane Sandy and others. I couldn't be in denial anymore. And as I looked down the barrel of what our future actually held I realized that the life that I had planned for myself this lovely life with being a clinical psychologist which is a wonderful field. Having a family and, you know, just a normal lovely life that it wasn't going to happen because civilization would be coming undone more and more due to drought, famine, state failure, chaos. That, yeah, I had to grieve the future that I thought I had but the wonderful thing about that is that when you do confront reality and realize that yeah the future that I was told about growing up all about progress and high hopes and possibilities that that is not accurate and instead we are facing a catastrophe of almost indescribable proportions. When you do realize that it opens up space to create another future first for yourself and then for as many other people as you can. So for me once I realized that the future I thought I had was ruined, I decided to go all in to everything that I could to protect humanity in the living world and that's why I started The Climate Mobilization.

Greg Dalton: And we’ll talk a little bit more about. Thank you for sharing that. Amanda Ravenhill. You work an institute named after a futurist. And you also think about individual trim tabs how individuals can have an outsized influence. So tell us how you think about individuals having an outsized impact.

Amanda Ravenhill: So Buckminster Fuller Institute is the organization that I’m honored to run. And Buckminster Fuller was a trim tab himself. He was a technologist kind of a techno-utopian but grounded in ecology. He’s inspired by nature's design and really a humanitarian at heart. So he talked about making the world work for 100% of humanity. He’s known for the geodesic dome which is really an artifact and a symbol of his underlying philosophy of doing more with less. So the dome is a structure that holds the most space with the least amount of material. He had many other artifacts that kind of are symbols of a feature that works for 100% of humanity. And he talked about being a trim tab. So a trim tab is a rudder on a small rudder on a ship it’s kind of the acupressure point within a system where the least amount of effort can cause a maximum effect. So instead of going pressing the front of a ship and expecting it to turn like so many of us are trying to do. It's about finding that point within the system where you can kind of almost play a trick. Where, you know, one little point of pressure can unlock so many kind of cascading benefits within a system. It can be used obviously for good or bad if you kind of put the wrong trim tab on something, it can cause all these unintended consequences. Which is why it’s so important to think in systems and ensure that we’re trying to create maximum benefit maximum co-benefits with every step that we take.

Greg Dalton: George Lakoff, you do a lot of writing and thinking about individuals the human mind and also think about system. So you think about climate change individual action and collective action. How should we think about this?

George Lakoff: Well, first of all, individual actions add up. All collective actions have to do with collectivities of individuals. Individuals affect each other. They affect each other in all kinds of ways who you know who you talk to who believes what you believe and so on. So you can't really separate out collective action from individual action. Collective action is made up of individual actions and individuals who know each other and form groups. So I don’t see those as separate issues.

Greg Dalton: But I struggle with people can act individually, but we want to think systemically. So how can a person think about a system that they can control but they’re part of?

George Lakoff: Well, I do a lot of work on systemic thinking. But I learned this very early, I was an MIT undergraduate in math and humanities both double major. And the thing about the math and the physics that I learned there was that you get a feel for how what the size of something was. For example, when I learned that the Earth had heated up by a degree I said, oh my God you don’t have any idea how much heat it takes to heat something as big as the earth by a degree. And I was just like, you know, when you go to MIT and you learn the math of those things you say that’s amazing that's horrific. I was overwhelmed by that and I still am.

Greg Dalton: So understanding scale but it's the scale I think often, Amanda Ravenhill, of the climate change thing that makes people feel so little and inadequate. It’s so big that I feel like an ant in the universe that I can't do anything meaningful.

Amanda Ravenhill: Yeah, yeah, it’s a hyper object it’s like impossible to actually put your hands around. But I think we’ve been talking about it all wrong like we've been talking about it as permanent. And if there’s one thing you’ll remember from this evening is that it’s that we can reverse global warming. And I think it's something that we don't talk about enough. We can actually get to global cooling and the most optimum scenario that we put together which is with all technology that we have available today and obviously they’ll be even better results with new technology that's coming on board. But just the technology we have today we can achieve drawdown by 2040. Drawdown is when we peak in concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and then temperatures come down about 10 years later. So my friend just had a baby when this baby is 30 years old we’re gonna have the coolest party ever because temperatures are gonna go down and I think knowing that it's temporary changes everything. It’s still kind of hard to put your arms around but knowing that it could be temporary if we all put our hearts and minds to it of course. I know for me I've been working in climate for many years. We started Drawdown in 2013 I’ve been working with 350.org since 2009. And no one had told us that it was temporary that it was possible to actually, you know, 350.org obviously were talking about getting CO2 concentrations back down. But it wasn't in the conversation that we can actually do this and it’s so, so critical as we’re grieving so much and rightfully so that we know that it's a temporary state. We can like put our hearts and minds to it and get there.

Greg Dalton: George Lakoff, that's a very positive message. Why doesn't that get through more? Because the climate conversation does seem to be one way down.

George Lakoff: There's a reason for this that has to do with linguistics. The right wing propagandist Frank Luntz invented the term climate change. The idea was to avoid global warming or global heating at all, which sounded like humans were responsible and climate change sounded like well climate is kind of nice you think of palm trees and, you know, change just happens, right. So the idea there was to take out all of the human responsibility in the linguistics of that term. And the right wing went out. Luntz got his term climate change in when nobody talks instead about global heating right now. If you talk about global heating every time instead of climate change, people would think about it very differently.

Greg Dalton: When the Tubbs Fire roared through Northern California in 2017, Jonah Gottlieb's house became a shelter for many of his teenage friends and their families. Gottlieb says he was already environmentally aware but the harrowing experience jumpstarted his activism. He soon became an advocate for children's health and education and participated in a climate strike in Washington DC. We asked him how becoming an extremely active leader has affected his personal life as a 17-year-old attending high school.

[Start Playback]

Jonah Gottlieb: My typical day as I go to class and then between every class and at lunch I'll be sitting at the front desk or in the nurse’s office or in a closet somewhere on my conference calls or writing emails or drafting legislation. And so it’s kind of removed me from the whole school thing. And part of that's a negative you know, and always thinking okay well if I could go to this party but, you know, I have that bill to write and if I don't do that, then that's another day out of the 10 years that we have left to take the action we need on the climate crisis. And so because I want to maintain my relationships with all my friends here, you know, it forces me to have some work-life balance. Then when I interact with them, I have to put my work on hold and remember to enjoy my life. Getting to be on conference calls with people around the country every single day of the week has, you know, really brought me really close with so many amazing people and amazing organizers that I otherwise wouldn't have had the chance to meet. I have this entire community of activists around the country who are doing this fight with me. I don't think people outside this movement realize how many young people there are just like me who are doing this work. There are thousands and thousands of young people who spends, you know, all their weekends all their free time all their lunches at schools on conference calls talking to each other talking to adults to get paid to do this work. And doing it all you know, not for money, not for the recognition not for the clout, but because there's no other option because the adults are failing us and so we know that it's up to us. And so it’s showing that you don't have to be a big fancy lobbyist to impact your government. I mean I can't vote in the California primary and yet I'd argue that my work has changed way more people's opinions and gotten way more people registered to vote, than my one vote ever could.

[End Playback]

Greg Dalton: That was 17-year-old Jonah Gottlieb, executive director and cofounder of the National Children's Campaign. And I just want anyone to think about when you were 17 if your thought was do I go to a party or do I write a bill. How many of us were in that position. Personally, I was not in that position. Amanda Ravenhill, he talks about the importance of relationship and it's interesting how he realizes there's some balance there. He's all in but he needs to kind of maintain his relationships. So I’d like to have your thought could you think a lot about it as well. The importance of relationships in sustaining people involved in this activity.

Amanda Ravenhill: So a lot of the work we do at Buckminster Fuller Institute is around regenerative projects. And so these are kind of nature inspired ways of healing the earth healing each other healing ecosystems, healing the climate. And essential tenet to that is being in right relationship which is something you find a lot in indigenous cultures and wisdom. And, yeah, a lot of it is just kind of understanding that we are not just islands unto ourselves that we are all in dynamic relationship to one another. And to appreciate and celebrate that I think that’s something that's been missing a lot from the movement is the celebration of what is working and celebration of what we do have celebration of a reverence for the interdependence that fuels life. And all of the kind of opposites of the root causes that have caused climate change. Climate change is just one festering wound of a whole array of root causes. And I think being in relationship to one another and preventing othering and racism and colonialism and all the other things that result from that othering is really critical. And so as we are looking at these climate solutions how can we do it in a way that addresses those root causes. And we're kind of identifying those at Buckminster Fuller Institute right now with a new project that we’re doing that’s called the design science decade. Which is something Buckminster Fuller launched in 1965 and we've rekindled for the 20s. And a lot of that is about kind of looking at the root causes and then how do we kind of address those as we’re moving forward and addressing these emergencies like climate and like others.

---

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation about Me versus We -- what matters more for climate action. Coming up, what role should fear and shame play in getting individuals or organizations to act?

MKS: World leaders, people in positions of power really all of us should be ashamed that we’ve let this get this far and this terrible. We are all perpetuating this system and this lie that it's somehow gonna be okay,

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

---

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton, and we’re talking about individual versus collective action with George Lakoff, Professor Emeritus of Cognitive Science and Linguistics at UC Berkeley; Amanda Ravenhill, Executive Director of the Buckminster Fuller Institute and cofounder of Project Drawdown; and Margaret Klein Salamon, a former clinical psychologist and author of Facing the Climate Emergency: How to Transform Yourself with Climate Truth. Margaret explains how being a low-carbon consumer often doesn’t translate into more important systemic changes.

Margaret Klein Salamon: Doing this work doing this political work and just spending time learning about these issues and knowing these people. It’s kind of inevitable that I have taken some steps whatever we have solar panels and so forth. But that's not politics and it's not how we're going to win. And I mean what you're calling individual action I think I might call like consumption purification. Whereas what Justin is doing is individual action, right. He's one person but what he's doing is leadership, right. He is building his own power and he is showing his peers that they also have power to transform the broken system rather than to try to be the best most pure consumers within a broken system.

Greg Dalton: Amanda Ravenhill, you put it a little bit differently. You think that the footprint the idea that goes around thinking about the carbon footprint maybe buying offsets agonizing over every many decisions. It’s a real source of contention in my home with my wife like really do we have to like every single thing think about a lifecycle analysis of everything that goes into the refrigerator, really? Amanda, you think that the footprint is important and reductionist. What do you mean by that?

Amanda Ravenhill: Yeah, so a lot of us are talking about kind of moving to zero and moving to having zero carbon footprint carbon neutral carbon, you know, moving to zero, more zero is one of the metaphors that people are using now. And yeah, I think it’s just looking at doing less bad and doing less bad is not gonna get us there. And so an alternative would be what’s your carbon handprints whether you able to do that other people aren't able to do that's gonna proactive that you’re creating more good in the world. I think more of us, we’re more capable than we know. And we have access to capital we have access to people we have access to all sorts of privilege. If you make more than $35,000 a year you're in the global economic 1%. Your money is not just sitting in the vaults of your bank and your credit cards it's being leveraged over and over again for the economy that we don't want. There's a lot that you're doing maybe passively with your cash. And it’s also the things that is, it’s a different mentality than just trying to go to zero. It's really saying like what can I put out there in the world.

Greg Dalton: The question of what can I do has always been part of the conversation about energy and environment. In 2001, VP Dick Cheney weighed in on the virtue of individual energy conservation and the context of national policy.

[Start Playback]

Dick Cheney: Already some groups are suggesting that government should step in to force Americans to consume less energy. As if we could simply conserve or ration our way out of the situation we’re in. Conservation is an important part of the total effort but to speak exclusively of conservation is to duck the tough issues. Conservation may be assigned a personal virtue, but it is not a sufficient basis all by itself for sound comprehensive energy policy.

[End Playback]Greg Dalton: VP Dick Cheney addressing reporters in 2001. George Lakoff, personal virtue, I’d like to address the personal virtue. Because lot of people go around lots of virtual signaling these days. I know, I’m doing my part on climate I'm a virtuous person, what’s wrong with that?

George Lakoff: Exactly the issue. It isn’t personal virtue, it’s being part of a community knowing community institutions and the values of those institutions and what they do. Knowing how communities and cities and states operate in general, which is more than personal. These are political things that are important. The idea that the virtue is in politics a lot. The question is in what politics where in politics who has what levers. And then what other civic institutions are there. The question is what are the institutions involved and what system of institutions matter and how can an individual connect to various institutions in a system to have some effect. And to know other individuals who can they can join with to have a greater effect.

Greg Dalton: Margaret Klein Salamon, I’d like to ask you about you change your sense of self when you have the transition you talked about. I’d like to hear your thoughts on people's self-identity as it pertains to what George have said.

Margaret Klein Salamon: So in this country we’re told from I mean basically birth that we are defined by our individual achievements and status and purchases buying power and that we’re just individual actors. And that mentality is the same mentality if I say okay climate change is real and I am going to get only zero carbon food and clothes and, yeah, my whole lifestyle. You're still in that individual frame of reference. But what I did is realize that yes of course we’re one individual the only person I can fully control is myself. But what if we have a bottomless responsibility to protect humanity and the living world and stop this catastrophe from fully unfolding. What if we are the heroes that we've been waiting for. So it’s really a very different core concept of who we are and how we relate to each other that if we’re responsible for solving this then the idea of competition like for example between organizations or organizers, forget it, who needs that. What we need is to build power until we can create unbearable pressure for our politicians and institutional leaders and turn this ship around radically and as soon as possible.

Greg Dalton: And Margaret you pointed out to me something that I remember experiencing but didn't really realize it at the moment that there was a particular before the midterm elections in November 2018, there is rebellion day one in the U.K. there was the Sunrise Movement occupying Nancy Pelosi's office. And that all those things kind of created -- tell us about the significance of those things coming together and then I'm thinking about what might happen in this fall with another election.

Margaret Klein Salamon: Yeah. So for the last several decades, the dominant paradigm in the climate and environmental movement has been gradualism. Meaning let's make small tweaks to our system over years and decades that kind of don't bother people that much and it’s very polite and technocratic. And in November of 2018 in the same week Extinction Rebellion shut down five bridges in London and the Sunrise Movement sat in with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in Nancy Pelosi's office calling for Green New Deal. And it was like the earth moved because that was when we really saw that gradualism as a paradigm is it's failed and it’s over. Leave it in the past because only emergency speed transformative change of all of our systems can protect us. And the only way we’re going to achieve those is building a movement that tells the truth acts like that truth is real and builds power.

Greg Dalton: We’re talking about individual and collective action, at Climate One. I'm Greg Dalton. My guests are George Lakoff, Author and Professor Emeritus of Cognitive Science and Linguistics at University of California Berkeley. Amanda Ravenhill, Executive Director of the Buckminster Fuller Institute and Margaret Klein Salamon, a former clinical psychologist and founder and Executive Director of the Climate Mobilization an advocacy group. George Lakoff, we’ve been talking a lot about youth and power. Greta Thunberg, Time Person of the Year, incredibly powerful. What is the power of Greta?

George Lakoff: How do you dare -- shame, absolutely. She said you are in charge of my future. How do you dare make it worse? Not only my future but the future of everybody my age. How do you dare make it worse? That's power.

Greg Dalton: And I thought also that she really called out adults who sort of pat kids on the head and say, you give me hope you'll solve it. And she's like no, no, no, you solve it now. Don't wait for us, right. That's a copout.

George Lakoff: Exactly. Exactly. It is a copout.

Greg Dalton: Margaret, I’d like to get your thoughts on the, you know, shame, oftentimes I’ve learned that shame is not a great motivator. That's like people feeling bad about themselves that’s not motivating. So, do you agree with like Greta’s power flows from shame and your thoughts about shame as a psychologist?

Margaret Klein Salamon: Greta tells the truth and she doesn't worry about whether that is making people feel uncomfortable or whether it's hurting their feelings or really anything. It's just the truth because that is so important on its own. So whether or not people have a positive or negative reaction to shame. I mean I don't think that's the defining question people, world leaders, people in positions of power really all of us should be ashamed that we’ve let this get this far and this terrible. And through and obviously there is varying degrees of responsibility but through passivity I mean merely just living your life as normal we are all perpetuating this system and this that it's somehow gonna be okay, or we’re not gonna just hit the apocalypse in just years or very few decades. So Greta, the reason that that's so hard to talk about for almost everyone is because we’re so socially attuned and we worry like, oh, if I talk about the truth of the climate then this person is gonna feel uncomfortable and this person might feel guilty or ashamed and this person might want me to, you know, leave the dinner party or whatever. They’re gonna think negative things about me and Greta is just over it. I mean she does not care she's just telling the truth.

Greg Dalton: Do you ever self-censor yourself in social situations?

Margaret Klein Salamon: Not really. I’m pretty over it myself.

Greg Dalton: Amanda, do you ever self-censor yourself in social situations about climate like, I can’t go there now, can I just live in this little bubble of denial for the next 30 minutes.

Amanda Ravenhill: No, not really. No, I don't like to live -- I mean there’s so much good news around it. I think I have a different view than most people. Like the crow’s nest upon which I stand on this spaceship Earth is there’s so much good news from where I’m standing. And I see climate as really a reason for this like global renaissance and changing so much of what we do, you know, and bringing about healing for all sorts of different systems. You know, I like to call this time the awkward era because the good news is getting better and the bad news is getting worse. And it's kind of hard to know you’re like awkwardly in between what's going on. And I think if we feed ourselves with the good news and really see that potential of this moment climate change is bringing us all together it’s making us see that we’re all one global community. It's helping us understand systems there's all of these. My husband here calls me the queen of silver linings. So this is my character. But I really do think that like I don't center myself around climate because as I'm sharing about it it’s kind of like it's our inevitable evolution where we’re finally looking to appreciate the health of ecosystems. And, you know, what we found with Drawdown was it’s a $74 trillion business opportunity too. So depending on what you kind of focus on in terms of the profits that you're looking to have in the world whether that’s financial profits or, you know, becoming better healers as a species. There’s so much good news around it that there's no need to censor to myself.

George Lakoff: What is this business opportunity that for some people here might be wondering about.

[00:47:14] Amanda Ravenhill: Electric vehicles is the number one business opportunity according to the model that we created. But there's so much, agroforestry, if you add up all the different agroforestry solutions and Drawdown becomes the number one solution. And that’s per acre you can sequester as much carbon as the average American emits in a year. There's so much that we can do that increases the livelihoods of systems, increases the nutrients in our bodies that, you know, increases the health of the microbiome in our gut and also the microbiome of the soil and really brings the earth back to life. You know, we’re down right now obviously with mass extinction, 80% of insects are gone by biomass. But we have to take that long view of this being temporary if we get stuck in the rut of not having as much life then that’ll be a self- fulfilling prophecy but if we know that it’s temporary we can take this longer view of kind of restocking the earth with life. And in doing so healing so many other things then yeah, it’s a completely different narrative than what you’re typically hearing in climate --

Greg Dalton: Can I call you when I get down and you just say that to me and can you just kind of like -- George Lakoff, that was a classic reframe. She took something that you know, so how can other people reframe it the way that don't have Amanda's innate optimism. And, you know, reframe climate as a huge wealth creation joyful opportunity.

George Lakoff: Basically, it's a technical linguistic problem. It is how do you take what you have and put into everyday language with everyday issues. Things that people encounter in their everyday lives so they notice it. If something is not named if there isn’t a word for it, you’re not gonna notice it. So it's important that we have words for all those things you’re talking about as they occur in everyday language not just this technical terms but as part of what you see around you. That is a matter of language creation. And language creation exists, it’s there every advertiser is involved in the language creation. And, you know, basically we need to understand what kind of language creation we need to be engaged in. What language we have to create how do we get it out there what are the ways to do this. How does the media help and so on. I mean this is a technical thing that has to do with our language and the way language gets into the population through the media. So, you know, unless you're talking about the media and how the media changes and how new language and new topics get into the media you're not gonna succeed.

Greg Dalton: George Lakoff, there’s a lot of talk about hope and optimism. What's the difference?

George Lakoff: Optimism, hope says there’s something impeding you. Hope says there’s something in the way and you got to get past it. Optimism, just says look ahead. You don't have to assume that there’s something impeding you just go and do what you need to do. Optimism has to do with vision, opta, right? It has to do with vision look at what's ahead and do it. Versus hope where there is something against it and you have to overcome what's against it.

Greg Dalton: So how do you feel about our climate prospects?

George Lakoff: We need to be optimistic.

Look, it’s very clear that there are things against it, you know, the coal and gas and oil industry is against it. There are lots of institutions in society that are against this. Their political parties there’s at least one political party that's against it, you know, that supporting the opposite view. And the question is how do you overcome all of those issues. Well, I think, you know you need to know what the problems are, but you need to be optimistic and just go for it.

Greg Dalton: You're listening to a conversation about what kind of action really matters for solving the climate challenge. This is Climate One. Coming up, getting past the individual “you” and “me” in order to maximize the potential of “we.”

Amanda Ravenhill: I’m so dedicated to this that I got a tattoo on my shoulder in the form of a bird emerging from an egg. We’re far more capable than we know we’re hatching into this new paradigm of the me, me, me and the egg to the we collective consciousness.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

---

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. [Climate One records many of our conversations with a live audience at our modern and green new home on the waterfront in San Francisco. We have suspended public events through April and possibly beyond. When we resume public events and you are in town come check us out. Our programs are open to the public and listed on climateone.org.] We’re talking about individual versus collective action with George Lakoff, Professor Emeritus of Cognitive Science and Linguistics at UC Berkeley; Amanda Ravenhill, Executive Director of the Buckminster Fuller Institute and cofounder of Project Drawdown; and Margaret Klein Salamon, founder and Executive Director of the Climate Mobilization, and author of Facing the Climate Emergency: How to Transform Yourself with Climate Truth. As a former therapist, Margaret knows how people have to confront some very difficult feelings in order to engage with climate.

Margaret Klein Salamon: Almost everyone in this country censors and judges their feelings. And this is as a therapist one of the main things that I worked with people on is to not do that to approach all emotions with compassion, curiosity and lack of judgment. There's no such thing as a thought crime or a feeling crime. The only thing that has a moral weight in the world is our actions. So, paradoxically, by allowing ourselves to experience our whole range of emotions even bad ones or irrational ones. We actually gain the most control over our actions because we can bring those feelings into a synthesis with our rational mind and our values and choose how we act. So everybody censors their feelings to some degree. And a lot of that it is gendered what we were told growing up. You know, boys don't cry, be a man, get over it or and you know girls shouldn’t be mean or angry or too kind of typical emotional patterns it's different for every person. But what's really important is that all of us feel everything. Again there’s just no such thing as a wrong feeling or a bad feeling and that's so important when we’re dealing with this climate emergency that makes us feel I mean anger, rage, despair, grief, terror, shame, guilt, everything. And so I think that kind of emotional overload is a big part of why so many people do kind of turn off shut this out of their mind. So if we get more comfortable just with the experience of strong feelings it can help us really be more effective in facing this truth and being a leader.

Greg Dalton: That was a long list of emotions, joy wasn't in there.

Margaret Klein Salamon: There is definitely joy I experience joy all the time and it comes from working on this problem using my capabilities and doing it with some of the most wonderful people in the world. Yeah, there’s joy.

Greg Dalton: George Lakoff, I want to ask you about the authoritarian parent and the nurturing parent. You've written about there’s different paradigms way different political parties. See the world the way they conduct themselves. And I want you to address that and then talk about the 2020 election.

George Lakoff: It's right there. We have an understanding of the nation as a family and what that means is that the kinds of parenting that enters into families metaphorically projects onto national politics. And right now we have a president who has all what I would call the strict father values. He is in charge. What is the strict father mean? A strict father says, I define what is right and wrong, right. And not only that, I reward what is right and I punish what is wrong. And the punishment has to be painful enough to make people stop doing what's wrong make children stop doing what's wrong. That's what a strict father does. And you map that on to politics and there is Donald Trump, you know, straightforward. And it’s funny I had written about this and I got a note from Donald Trump Junior who said I didn't have a strict enough father.

Just thought you’ll enjoy that.

Greg Dalton: Some people would say the antidote to the strict authoritarian father would be a nurturing parent. Do you see a nurturing opposite to that in the Democratic field?

George Lakoff: Nancy Pelosi.

Greg Dalton: Or Michelle Obama.

George Lakoff: Or even Barack. I mean, yes, these are caring people who hacked so that the caring works, you know. Nancy Pelosi is one of the most effective political figures of our time. Now caring has to do with a couple of things. One, it has to do in a democracy with providing public resources for everyone. The other part is a government of by and for the people, you know, Lincoln got it right. So you have a government of by and for the people and the government that provides public resources for private life and private enterprise. Those are what government is about or should be about. And if they’re not about that there’s something wrong.

Greg Dalton: We’re gonna go to our lightning round and I invite our guests to write yes or no quickly to true or false to these questions. Beginning with George Lakoff. True or false, George Lakoff. Liberals hate repeating themselves?

George Lakoff: Yes, true. And it’s sad.

Greg Dalton: Conservatives know repetition is the key to a winning message?

George Lakoff: You have to have repetition.

Greg Dalton: Amanda Ravenhill. True or false, empowering women and family planning are two large climate levers that people don't know or talk about enough?

Amanda Ravenhill: True.

Greg Dalton: True or false. Margaret Klein Salamon, you used to live your life as a resume polisher?

Margaret Klein Salamon: True.

Greg Dalton: And also for Margaret. Now you're a climate warrior?

Margaret Klein Salamon: True.

Greg Dalton: Amanda Ravenhill. True or false, anything that feeds apathy is dangerous?

Amanda Ravenhill: True.

Greg Dalton: Margaret Klein Salamon. A person who has a big carbon footprint and claims they care about climate is a hypocrite with low credibility?

Margaret Klein Salamon: Sometimes true.

Greg Dalton: True or false. George Lakoff, you have made personal sacrifices to reduce your carbon footprint?

George Lakoff: It's an interesting question.

Greg Dalton: You wrote a book about that I know.

George Lakoff: Right. But because I don't see the sacrifice. I mean I see it as a way of life.

Greg Dalton: So it's about the frame?

George Lakoff: It’s about that.

Greg Dalton: True or false. George, you feel guilty about your personal carbon footprint?

George Lakoff: No.

Greg Dalton: Last one for Margaret Klein Salamon. Some people view your organization as full of jerks.

Margaret Klein Salamon: Sometimes.

Greg Dalton: Alright let’s give them a round of applause for getting through the lightning round.

If you’re just joining us I'm Greg Dalton. We’re talking with George Lakoff, Amanda Ravenhill and Margaret Klein Salamon at Climate One about individual action and collective action. What we can do to address climate change, individually and collectively. We’re gonna go now to our audience questions, welcome.

Male Participant: Thank you. My name is Matt Renner George, I just want to get up and thank you --

George Lakoff: Hi, Matt.

Male Participant: -- hey, and tell you how much I love you and appreciate you.

George Lakoff: Good to see you, Matt.

Male Participant: And your class just speaking of individual action set me on my personal path. And I want to give you a softball, you know, I want you just talk a little bit about your legacy in terms of the impact one person can have in a lifetime, from a place I’m just really appreciating everything you've done for me.

George Lakoff: Well, Matt is a very good example of one of the more than 10,000 students I've had over 50 over more than 50 years of teaching. When you teach, I taught at Berkeley for 44 years and at Harvard and Stanford before that. And 51 years of teaching means you teach a lot of people. And in a way it doesn't matter people would think well what I do is I teach cognitive science I teach linguistics and I teach application of that everyday life and politics, right. And when I talk about politics people in my department got very unhappy and as I said I got denied promotions for writing books that talk about politics, too bad. And what the point was that I've had over 10,000 people like Matt. And in these classes that is an amazing thing to be able to do. To be able to teach 10,000 students in 50 years is a wonderful thing. I couldn't think of a better way to spend my life.

Greg Dalton: And George it’s not just your students. I never took a class from you but I consider myself one of your students. I learned a lot from you and I’ve interviewed thousand people in climate and I've learned a lot from you as well. So thank you for that. Next question. Welcome.

Female Participant: Thank you. Hello, my name is Shana Rappaport. This question is for Amanda Ravenhill whose middle name by the way, is literally joy. I’d love to also hear Margaret’s thoughts on this question as well. And it comes back actually to the subject and title of this evening's event, which is me versus we. And I think there were threads that addressed this but specifically I would love to hear a little bit about like for example I work a lot with many of the biggest companies in the world on advancing climate progress. How do we actually shift the paradigm while we’re still existing in this current system of maximizing short-term profits maximizing individual gain to one that truly includes the collective we.

Amanda Ravenhill: Thank you, Shauna. So Buckminster Fuller did this really great analysis around 1970. And he said that we actually have the technological capability of taking care of everyone on the planet at a higher standard of living than any have ever known. And that it no longer has to be you or me but really we. He said it would take about 50 years, do the math, from 1970 for us to kind of wake up to this new reality and that we would build all the kind of right tools for the wrong reasons first. And so I think we’re far more capable than we know kind of translating what we have now into this new paradigm and I think we’re much farther along than we can consider. I’m so dedicated to this that I got a tattoo in my shoulder in the form of a bird emerging from an egg which is a story that Buckminster Fuller tells about kind of this state change that we’re going through similar to water freezing or a caterpillar turning into a butterfly where this egg emerging where, you know, far more capable than we now are hatching into this new paradigm of the me, me, me and the egg to the we collective consciousness.

Greg Dalton: Margaret.

Margaret Klein Salamon: Yeah, the only thing that I think I really want to add is I think what ultimately is going to get us there is the understanding that on our current path our current narcissistic, individualistic path lies only devastation. That we really don't have a choice or actually we do have a choice but the choice is collapse or transform. And so what has previously been viewed by many as altruism versus selfishness what we’re realizing when we see what's happening on our planet is that really there's only one way for any of us even individually to have a future and that is for all of us to come together. And I love the quote but yet to make a planet that works for everyone.

---

Greg Dalton: You’ve been listening to Climate One. We’ve been talking about individual versus collective action with Margaret Klein Salamon, founder and Executive Director of the Climate Mobilization, and author of Facing the Climate Emergency: How to Transform Yourself with Climate Truth; Amanda Ravenhill, Executive Director of the Buckminster Fuller Institute and co-founder of Project Drawdown; and George Lakoff, Professor Emeritus of Cognitive Science and Linguistics at the University of California Berkeley.

Greg Dalton: This conversation was recorded in late February, before coronavirus was declared a global pandemic. As I’m recording this the city of San Francisco has just issued an order to shelter in place which will impact our ability to produce our podcast and radio show. We have pulled excellent shows from our archives for the next couple of weeks and are planning in future episodes to explore how the response of humans, societies and governments to coronavirus informs what we know about the response to climate disruption. Though the causes are unrelated, there are some scary and fascinating parallels around how we cope with societal disruption, evaluate risk, and mobilize rapidly to address a global problem.

Greg Dalton: Kelli Pennington directs our audience engagement. Tyler Reed is our producer. Sara-Katherine Coxon is the strategy and content manager. Steve Fox is director of advancement. Devon Strolovitch edited the program. Our audio team is Mark Kirchner, Justin Norton, Arnav Gupta, and Andrew Stelzer. Dr. Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, where our program originates. [pause] I’m Greg Dalton.