McKibben and Tamminen: Disruptive Climate and Politics

Guests

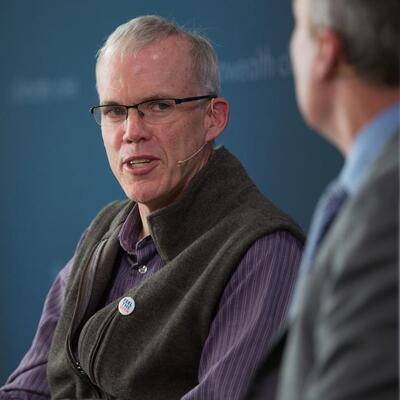

Bill McKibben

Terry Tamminen

Summary

Climate change seems to have taken a backseat in this year’s presidential campaign. What’s ahead for the climate movement in the next administration?

Bill McKibben, Founder, 350.org

Terry Tamminen, CEO, Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation

This program was recorded in front of a live audience at the Commonwealth Club of California on October 21, 2016.

Full Transcript

Our disrupted climate has barely been a sideshow in the disruptive presidential election. The most memorable moment came not from Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump but from Kenneth Bone, a worker at a coal plant who became an Internet sensation after standing up in his red sweater and asking about the future of jobs in fossil fuel industries. While politicians have been mostly ignoring climate change, Florida has been flooding during sunny days, temperatures have been rising and the growth of clean energy has continued. Bloomberg News reported the number of U.S. jobs in solar energy overtook those in oil and natural gas extraction for the first time last year. Clean energy jobs are forecast to triple over the next 14 years to 24 million worldwide.

Over the next hour we will take the temperature of the clean energy economy and the climate debate in this wacky political year. Joining our packed audience at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco, we’re pleased to have with us two energy experts active in Democratic and Republican circles. Bill McKibben is perhaps America's most visible environmental advocate. In 1989 he wrote “The End of Nature” regarded as the first book for a general audience about climate change. He founded the grassroots organization 350.org to mobilize people around the world on the need to get off fossil fuels. He worked on the Democratic Party's national platform as a delegate for Bernie Sanders.

From the other side of the aisle, Terry Tamminen was chief policy advisor to Arnold Schwarzenegger when he was governor of California. He has advised Walmart on its energy strategy and a private equity group founded by the veteran of the Wall Street firm Drexel Burnham and Lambert. He’s currently CEO of the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation. Please welcome them to Climate One.

[Applause]

Welcome both. So Bill McKibben, talk to us about climate in this election. It's barely mentioned on the edge of the debate. It hasn't been a central issue in this wacky political year. Does that mean it's not important, tell us, where does climate sit in this election?

Bill McKibben: It was a big issue in the primaries, at least on the Democratic side. And it was wonderful to see a high point in the entire climate story politically in this country was when at the first debate they asked people what the most important issue in the world was and Bernie Sanders forthrightly said climate change as if it was the most obvious thing in the world, which it is. And in this general election truthfully, all issues of substance have disappeared. The only question we’re left with is, you know, how can we prevent a creepy pervert from becoming, you know, president of the United States.

[Laughter]

And I mean, that’s kind of where we are. And there's been nothing else that we've really had any chance to talk about. But, you know, we’re in the hottest year that we've ever recorded on our planet. I have not the slightest doubt that the minute that the election is over, that the climate movement is going to be pushing and pushing hard for real action. Because we can't, we have no more four years’ to waste, I mean we’re out.

Greg Dalton: Terry Tamminen, in 2008, John McCain and Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama basically agreed on climate change, and then there was this big divergence. So how do you see that and where we are in this political season from the Republican side?

Terry Tamminen: Well first of all, I want to thank you for hosting this discussion because it couldn't be more important given as Bill said that unfortunately so many other silly things have taken up so much of the national discourse. You know, and even before that, when I was in the cabinet of Governor Schwarzenegger, and by the way, despite the way your introduction characterized me, I’m not really on the other side. I was one of those stealth Democrats in a Republican administration.

Greg Dalton: Fair enough, yeah.

[Laughter]

Terry Tamminen: But, you know, but obviously it wasn't hard to get someone like Arnold who many people don't consider a Republican to move in the right direction. But even back then in 2004, ’05 we we’re working with Governor Charlie Crist, a Republican in Florida and a guy named Marco Rubio, who some of you may have heard of who at the time was the speaker of the assembly, on a climate bill and on climate solutions. And in Florida they found the same thing that we found in California was that what was going to be good for the economy, for the environment was good for the economy. There was an Agriculture Commissioner by the name of Charles Bronson who was about as right wing as you can get, somewhere near Attila the Hun. And yet even he loved the idea that you could take agricultural waste and turn that into biofuels.

What's unfortunate is by the time we got to 2008, even John McCain who was very supportive of those kinds of things, not to mention the Marco Rubios of the world, started to back off because they became hostage to the tea party and the other extreme right-wingers who not only didn't believe in climate change, but were basically being fossil fueled by the Koch brothers and the denial industry. So it's really sad to see Mitt Romney even more recently, who was one of the founders of the first major cap and trade system in the United States for carbon, had to back off and pretend like he didn't really believe that climate was such a big problem and suddenly decided to join the NRA for some reason. But there’s just a whole host of unfortunate circumstances that I think have shifted even moderate Republicans, not just to the right, but into being climate deniers.

Greg Dalton: Bill McKibben, one reason that politicians don't talk about it a lot is because the conventional wisdom is that voters don't vote on energy and climate. They vote on pocketbook issues, you know, highly charged social issues that environment ranks low even for Democrats. So therefore politicians don't talk about it because voters don't vote on those issues.

Bill McKibben: Everybody, I mean that is sometimes the conventional wisdom. I think it's really been upended in the last couple of cycles. If nothing else, it's what young voters are voting on. Often the number one or number two issue that those 18 to 29 or however it is that the pollsters slice them up votes on and that's beginning to tell on our political system. You'll note that, you know, four years ago it wasn't just Mitt Romney who didn't want to talk about climate change, neither did Barack Obama. They made it through the entire campaign without even mentioning it. This time, the Democrats are happy to try and talk about it.

Hillary's mentioned it a few times in the debate so they haven't, no one's asked a question about it. They perceive it now as an area where the Republicans clearly look bad because they're completely out of touch with science and everybody knows why. Just for the reasons Terry said, because they’ve allowed the party to become a kind of subsidiary of the fossil fuel industry. And so it's the political valences changed some, but David Leonhardt of the Times had a good piece today just about among other things, the failure of journalism. I mean none of the debate moderators managed to ask a question about it, even though they had plenty of time to ask about all sorts of other things.

Greg Dalton: Income inequality is a big issue in this country since the great recession. Bill McKibben, there’s a sense that even some of the policies that are addressing climate change aren’t working for everyone. They’re not including communities of color, even though African-American and Latino voters are more likely to support climate action. So talk about inclusion and the idea that this is a, climate is a kind of white coastal concern.

Bill McKibben: Yeah, I think again, I think that that's wrong. You know, truthfully, I mean think about our politics. White people are the problem for the most part. If we had, if we had the presidential election today just among white people, Donald Trump would win and pretty easily.

What does that tell you? Climate change fights are being led by front-line communities by communities of color, at the moment by most nobly by indigenous communities especially up in the high plains where everybody's gathered to fight the Dakota pipeline. These are the people who are in the lead of this fight. And you're right, policy has to reflect that. We need policy as we try to deal with climate change. That means that the people who got left out of the last economy don't get left out of this one; that the people who got dumped on literally in the last economy are first in line to benefit from the switch to a green economy. That's really important.

Greg Dalton: Terry Tamminen, 2010 then Governor Schwarzenegger successfully run a campaign against an initiative to undercut California's climate law and mobilizing the Latino community was instrumental in that vote when California voters overwhelmingly supported California's climate law. So did that lead to lasting involvement in the Latino community in environmental issues in California or has that faded since.

Terry Tamminen: Well, I’d say it led to lasting engagement by a variety of communities. Because the fact that most people don't know from that campaign, we were actually losing that because out-of-state oil companies came in and put lots of millions of dollars into ads to try to overturn our Global Warming Solutions Act. And it's always hard for the nonprofits and others who care about these issues to raise enough money to countermand that.

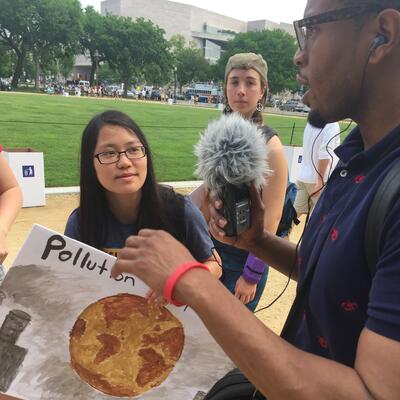

And it wasn't until the American Lung Association came in and ran ads about how overturning AB 32 would undermine other environmental laws your kids would have asthma as a result, that all of a sudden the numbers changed. So what we learned from that was that of course everyone cares about their kids. And I'm very glad by the way to see some young people here today who are going to be voters in maybe 10 years.

[Applause]

Because no matter where you come out on these issues later on in life it's important to have eco literacy, environmental literacy so you can understand these issues and then vote and vote with your pocketbook accordingly. But I think what that campaign in 2010 showed us was that we have to make this relevant to people in the most visceral sense. And that of course very often it is the communities of low income or color that are disproportionately impacted because they live downwind of the refineries or they live in other areas that have been more impacted than others.

Greg Dalton: I'm Greg Dalton and this is Climate One from the Commonwealth Club today, talking with Terry Tamminen, former chief policy advisor to Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and Bill McKibben, the author and climate advocate. I want to talk about Secretary Clinton, the election. In 2010, I sat down with Hillary Clinton just about six years ago and she talked about a pipeline that no one had ever heard of at that point. I want to get a reaction to this. We'll talk about Secretary Clinton’s energy platform. This is Hillary Clinton at Climate One at the Commonwealth Club in 2010.

[Clip]

Greg Dalton: How can the U.S. be saying climate change is a priority when we’re mainlining some of the dirtiest fuel that exists?

[Applause]

Hillary Clinton: Well, there hasn’t been a final decision made. It is --

Greg Dalton: Are you willing to reconsider it?

Hillary Clinton: Um, probably not. And, you know, but we haven’t finished all of the analysis. So as I say, we’ve not yet signed off on it. But we are inclined to do so and we are for several reasons going back to one of your original questions, we’re either going to be dependent on dirty oil from the gulf or dependent on dirty oil from Canada. And until we can get our act together as a country and figure out that clean renewable energy is in both our economic interest and the interest of our planet --

[Applause]

[End Clip]

Greg Dalton: So Bill McKibben that was Hillary Clinton six years ago. Get your comment that was a pipeline that no one ever heard of at that point and that became pretty famous piece of metal.

Bill McKibben: You had to show that. I've been off in Ohio and Pennsylvania trying to register young voters to make sure they’d be voting for Hillary and all this and it’s but it’s not with any great enthusiasm, I must say. Given the alternative, it's obviously necessary, but there is no question that she is, you know, that she was wrong on Keystone and has been wrong on a huge number of other things. The great news about, the fight about the Keystone Pipeline was not just that with the help of a lot of people in this room, we managed to beat the Keystone Pipeline.

It's that having seen that now, people everywhere around the world, having been proved that it's possible to be big oil, now fight every damn pipeline coal port, oil train I mean just down here in the city of Benicia just a couple weeks ago. People won a huge pitched battle against a new oil train terminal, you know, on and on and on. The head of the American Petroleum Institute gave a talk to some of his peers at a conference a few months ago and said with great regret and lament that somehow they had to stop the Keystone-ization of all their projects. And I confess my twisted shriveled heart gave a little leap when that, you know, when he said that.

Right now, the biggest fight as I said before is this Dakota Access pipeline. It’s utterly craven that Hillary Clinton hasn't said a word about it in the course of this election, really craven. And we will push her; everybody should push her as hard as it's possible to push. You know that she didn't say anything after the oil company used dogs to attack nonviolent protesters was -- her silence was almost as well wasn't as horrifying as the act itself, but it was not a good sign. What it means is the reason that we have in my mind elections is not to elect saints, it's to elect people that it's possible for us to then pressure and that's what we will try to do.

The honeymoon is going to be 10 minutes long, you know, and then we’re at work. One of the things that we managed to get in the Democratic platform thanks to Bernie's staunch refusal to concede until the last possible minute. One of the things that's in there is a promise that there will be an emergency climate summit within the first hundred days of the new administration. So if that happens --

[Applause]

Yeah, it’ll be good to have like all the scientists. If that happens, we need an emergency climate mobilization in the streets, in Washington. We’ll need hundreds of thousands of people here so save up what of your carbon footprint you can for the trip across the country come next spring.

[Applause]

Greg Dalton: The Paris climate deal was a pretty big deal virtually every country in the world coming together. Terry Tamminen, Arnold Schwarzenegger helped lay the groundwork for some of that. But some people think the Paris deal doesn't go far enough. Is it a good deal or is it something short of what we need?

Terry Tamminen: Well look, you buy a house most people can't afford to pay cash, you put down a down payment and that's what this was. Its biggest weakness, the fact that it's voluntary is also in many ways its biggest strength. Because as those of you that know the nomenclature COP21 was the 21st time countries got together on an annual basis to try to reach that agreement, so it took 21 years to do it. So the fact that they did it, and they all voluntarily said, “Okay, here's what our country can do after a lot of thought, with climate action plans behind it, and so forth” is a significant step because they weren't sort of browbeaten into it and then later on finding ways to back out.

This is what they stepped up and said they could do. And so like I said, that can be its greatest weakness. There's no way to enforce it, but it can also be the greatest strength because you’re seeing what they can really do. Collectively, it adds up to about half of what I think most people would think we’re going to need to do to lower our carbon intensity globally over time. So again, now you can measure how much did that agreement represent assuming we get everything done that’s in it, which again is still the jury is out. But I also think that it represents the biggest business opportunity in the history of the planet. Because every one of those countries, INDC is a well avoid acronyms, but you can go look it up on the web.

Greg Dalton: Carbon diet plans, yeah.

Terry Tamminen: Yes, carbon diet plans is very specific. It says okay in my country I'm going to get my reductions with this percentage of renewables and this percentage of fuel switching and this percentage of a market mechanism and so forth. So if you look at all those 190 plus countries and you map them out and you say okay, where is all the solar going to be? And I'm going to be a solar energy developer.

Now I know exactly where to go and where the government will be welcoming where there might be incentives or land that allows me to go do what I want to do et cetera or if I've got a technology to convert waste into some kind of a valuable product, I know where to go. So if people know how to read this agreement and read the commitments made by these countries. I think it's a huge opportunity for us to turn this thing around.

Greg Dalton: Bill McKibben, what would you like to see from President Clinton to advance the Paris climate deal?

Bill McKibben: So, there are, I mean the answer in a certain degree depends on whether or not she has a Congress that she can work with or not. I think it's, let's assume for the moment that she's probably going to be working with executive action which will make certain things like a price on carbon difficult. We've got to keep fossil fuel in the ground. That's really the, you know, job one maybe. And it's within the president's power to do an awful lot of that with after a lot of pressure; President Obama said that we’d no longer be leasing federal land for new coal development. We should be doing exactly the same thing with oil and gas. I think that's something like half the carbon under our borders and we need remarkable support for a rapid buildout of renewable energy. I did a piece this summer that was really an attempt, you know, people talked over and over and over again about, oh we need a World War II scale mobilization, I've heard this many times, you know,

Greg Dalton: Moonshot, right.

Bill McKibben: And so I actually went and tried to figure what that would mean just numerically. And, you know, thanks to Mark Jacobson's work at Stanford we know basically that it's how much stuff we’d need to build. It looks like you could probably build enough factories quickly enough to build those solar panels and wind turbines. It's on the outer edge of the doable but that's where the World War II part comes in.

I mean we’re a country and a world that’s good at this kind of thing. You know, within eight months in Michigan during the outset of World War II we’d built the biggest factory in the world and it was producing a bomber aircraft, which is a big thing with 300,000 rivets. One was rolling off the line every hour. We should be able to build solar panels and turbine blades at scale, but it will take real support and real focus to make that happen. Clearly one of the first things that President Clinton is going to be talking about it, so she said is infrastructure investment. That infrastructure investment has to go for renewable energy and none of it can go for building more fossil fuel stuff. That era has to close.

We had the most important study in a long time, came out three or four weeks ago from Oil Change International in DC. And it said the existing coal mines and oil and gas fields that we already have in production, never mind the reserves that we know about and that they're planning to dig up, already in production takes us past the 2 degrees that we agreed to in Paris. That means no more building anything at all in that fossil fuel world. We have the few years that it will take for those coal mines and oilfields to dwindle in order to make the transition to renewable energy so we’d best do it at full speed.

Terry Tamminen: Let me add two secret weapons to that. One is energy efficiency. And this is something the government can commit to support even within its own buildings within university campuses in it, and so forth. You know the Sears Tower in Chicago now called the Willis Tower; it was the tallest building in North America for quite some time. They went through an energy efficiency retrofit of insulation of their heating and cooling and so forth and lighting.

And they saved 80% of the energy that that building used when it was first built in the 1970s, 80%. So imagine how much energy that frees up on the grid in Chicago to put in let's say battery charging stations for cars or just to mean that there's less solar and wind that we have to build so quickly. So, to the point that we do have to kind of have a wartime footing, in fact, if we put people to work making all of our energy use is much more efficient. That's a lot of jobs that can't be exported and it pays for itself because of in this case, the Sears Tower was about a seven-year payback. So that's going to have a tremendous --

Bill McKibben: And it’s worth remembering that World War II turned out to be the great economic stimulus that built the prosperity that America's, you know, that our sort of standard of living rests on in many ways.

Terry Tamminen: Exactly. And the second secret weapon I want to mention is waste. Because today 40% to 60% of the waste that goes to landfills in our country and all over the world is organic. So it’s yard clippings, it’s food waste, it’s agricultural waste. And if you were and right now that is largely decomposing into methane which is 20 some times more potent as a heat trapping gas than CO2. And if you were to take that material alone and turn it back into food, into fertilizer, into green chemicals, and so on, just that, let alone all the other stuff that goes into landfills that could be used, the plastic instead of digging up new oil you could use the existing plastic and so forth. The technology is all there. So working with city governments that control waste and control landfills obviously you need to start with source reduction, you need to recycle what you have. But whatever ends up going toward that landfill today could be productively used again creating a lot of local jobs and economic value and reducing the pressure on our climate.

Bill McKibben: Amen.

Greg Dalton: Terry Tamminen, on energy efficiency, Fox News, Network Fox Entertainment Corporation has pledged to go carbon neutral, might surprise some people. And one of the leaders of that James Murdoch, Rupert Murdoch’s son, led that effort. So tell us about what he did and he found in that taking Fox carbon neutral.

Terry Tamminen: Well like many companies, Walmart and others, they discover that this was just good for the bottom line. So it allowed them to maybe do a little greenwashing, some people might call it. But the truth is, it was good for the environment and good for the economy. In his case, they discovered at the time that I met him several years ago when Tony Blair was just leaving office in the U.K. He was the head of Sky News, a division of Fox and they discovered that they could offset 100% of their corporate carbon footprint simply by replacing the set-top boxes, cable TV boxes on all the TVs in their service territories with more efficient ones that reduced the energy consumption. But those newer ones also allowed them to sell more product over the Internet than over those boxes. So not only did their consumers save money who were obviously paying for the electricity, and it offset a lot of carbon. But then the company was able to make more money by selling more things through that channel.

Bill McKibben: It must be said that Fox has figured out some other ways to produce hot air that may --

[Laughter]

Terry Tamminen: Offset that.

Bill McKibben: --yeah, offset that yet again.

Terry Tamminen: Family feud.

Bill McKibben: And it brings a real, I mean it does, it’s a good reminder of how important the kind of cultural and communications and information work is. And that's a place for, you know, you and Leonardo DiCaprio are doing such amazing things. Shouldn’t you do a little plug for the new movie that --

Greg Dalton: Tell us of -- he has a new film out.

Terry Tamminen: Absolutely. It’s called “Before the Flood” it’s a documentary for those of you who may have seen “Inconvenient Truth” Al Gore's documentary 10 years ago. Everything that Gore warned us about in that movie, Leo takes you around the world and shows you is happening today and at a much accelerated pace. And just right here in our own country, he spent some time with the mayor of Miami Beach as an example. And they’re spending $400 million to elevate roadways and have new pumps to pump water out from flooding that now happens. Thanks to sea level rise even in clear weather, not even when there's hurricanes. And $400 million that we could've averted spending if we had tackled climate change sooner.

Greg Dalton: We’re talking about climate change at Climate One at the Commonwealth Club. I'm Greg Dalton. That was Terry Tamminen, former chief advisor to California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger. Now head of the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation. Our other guest today is the activist and author Bill McKibben.

We’re going go to our lightning round which is a series of yes or no brisk questions for our guests. Starting with Terry Tamminen, true or false a few years ago biologist named a new species after Bill McKibben?

[Laughter]

Terry Tamminen: I don’t know on these lightning rounds. I always just think of the word pizza. I don't know why that is but I'll say that's true.

Greg Dalton: Bill McKibben, name that species.

Bill McKibben: I can't name it. It was, I can't pronounce it. But they're very kind it's described as a pesky woodland gnat.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: Somehow appropriate for a man who is in the woods.

Bill McKibben: Entirely appropriate.

Greg Dalton: Bill McKibben, yes or no. Terry Tamminen is an accomplished skydiver?

Bill McKibben: I didn't know that. I knew about his work under the water.

Greg Dalton: He's not a skydiver. He is a licensed helicopter pilot. Bill McKibben, when Terry --

Bill McKibben: Also, must be said has remarkable history in the oceans and with some of our most charismatic and important species on this planet. Thank you for that work.

Greg Dalton: Founded a, yeah, ocean conservation organization. Bill McKibben. When Terry Tamminen took the helm of the California EPA under Governor Schwarzenegger, true or false the Los Angeles Times published an article about him that said, he once was, “A Malibu pool cleaner and part-time actor with a gift for charming, influential people and a resume that chronicled more rambling than a Jack Kerouac novel.”

Bill McKibben: From Australia to this from the antipodes to the Pacific Coast absolutely.

Greg Dalton: It’s true. Terry Tamminen, true or false. Bill McKibben met his wife while sleeping on the streets of New York?

Terry Tamminen: Hmm.

[Laughter]

I don’t know, if you said in the redwoods or something I might be more inclined to say yes. I'm going to say that's false.

Greg Dalton: He actually met his wife while he was a New Yorker writer doing a piece on homelessness and had living on the streets. And she's a homeless was then a homeless advocate. Bill McKibben, true or false. Blocking the Keystone XL Pipeline empowered the environmental movement and was a big symbolic victory?

Bill McKibben: I don't think there's anything symbolic about it really. I mean it became an iconic fight, but I think it was extraordinarily practical. It's done a lot to help investors and governments and everyone else understand that they no longer get to build this stuff, at least without a huge fight. And that there is, that the premium that they pay in money and political capital and everything else is going to be steep. And so we’ve seen people backing off place after place after place, amazing activists around the world who have shut down plans for what would've been the biggest coal mine in the world in Australia. All the coal ports that they planned to build along the West Coast of the U.S. I think five of the six have now been beaten, you know, on and on and on. We don’t win all these fights, but now we win some of them, and that's enough to begin to change this dynamic I think.

Greg Dalton: Terry Tamminen, killing the Keystone XL Pipeline did not keep tar sands oil in the ground. It actually resulted in more tar sands oil transported on dangerous oil trains, railcars going through American and Canadian communities?

Terry Tamminen: That's true. Unfortunately, they’ve also spilled just as much as these leaking pipelines. I wrote a book called “Lives Per Gallon: The True Cost of Our Oil Addiction” and talking there about how pipelines, and this is before the Keystone fight, pipelines were leaking more every year onto American soil and into American waterways than the Exxon Valdez every single year.

So it's, I agree with Bill that it was more than a symbolic victory because it highlighted that entire industry and the problems associated with it, but it didn't go away as you point out.

Bill McKibben: And it turns out that actually there's very little coming out of Canada on trains because it's way too expensive to do it. That oil is of marginal value anyway with the price oil what it is, no one's, I mean there are tens of billions of dollars in new investment in the tar sands has disappeared as these fights go on. Their plan, when the Keystone fight began, their plan was to triple or quadruple production out of the tar sands. They're going to be very lucky to hold it steady because they get that at every turn with real opposition.

And you just, what's going on in the Dakotas with indigenous people in this country is going on across Canada with indigenous people there who have managed to block one pipeline after another. The rise of indigenous environmentalism and indigenous activism around the country, around the world in the last 10 years is one of the great untold stories of this fight. You know, these are people who were pushed to the margins on land that nobody thought had any value so they were allowed to keep it as the small fragment of the continent that they once owned. And it turns out that they’re in all kinds of strategic places and boy are they using that with great power and wisdom.

Terry Tamminen: And sadly unprecedented levels of them being killed for their activism and for speaking out. So that's another thing we need to try to help them shine more light on these issues.

Greg Dalton: Bill McKibben, yes or no. You think nuclear power needs to be part of a balanced energy diet to protect the economy and the climate?

Bill McKibben: I don't think it's going to play hardly but I think it's going to play a minor role going forward. We could talk all day about the safety stuff and probably should, but I think the real issue is, you might as well burn $20 bills to generate electricity. You know, even you know, we watched your local utility decide that it couldn't make money even with the existing nuclear power plant, because the cost of renewables, I mean, all you have to do is look at the cost curves. Nuclear plants keep getting more and more and more and more expensive with each passing year and sun and wind are on the exact opposite plummeting cost curve.

Greg Dalton: And California is actually closing its last nuclear power plant for that reason. Terry Tamminen, this is a word association. First word that pops into your mind when I mention this phrase. Terry Tamminen, the merger of Tesla and its cousin company SolarCity.

Terry Tamminen: Pizza.

[Laughter]

I’m sorry. Brilliant or disaster.

Greg Dalton: Bill McKibben, hydrogen powered cars.

Bill McKibben: I think this is one of those technologies that probably just didn't work out the way we thought and we’re not going to need them because we’re just going to plug them into a wall.

Greg Dalton: Terry Tamminen, biofuels.

Terry Tamminen: Potential as a bridge.

Greg Dalton: Terry Tamminen, what do you think of quickly when I mention Arnold Schwarzenegger’s movies?

[Laughter]

Terry Tamminen: We want to pump you up.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: Bill McKibben, Arnold Schwarzenegger's climate policies.

Bill McKibben: Well I know, I mean, Terry, and you know, Terry can talk more about the actual specifics of the policy. It was very useful to have someone willing to make the case from the Republican Party that a) climate change was real and b) that the economic future lay in solving it, not ignoring it. Those were very useful things. He was a pretty much a sui generis character. There's really no, I can't think of any other equivalent in the Republican Party anymore, which makes me think that it had more to do with California than it did with Republicanism at some level. But it was a useful thing to have.

Greg Dalton: Last question in our not so lightning round.

[Laughter]

Bill McKibben, true or false. Leonardo DiCaprio has pledged sexual abstinence until the world ends its addiction to fossil fuels?

[Laughter]

Bill McKibben: So I want to say something about a --

[Laughter]

-- I want to say something about his enormous value. We --

[Laughter]

-- we had a press conference in Paris, I think in Paris last year about this big fossil fuel divestment movement, you know. And it was to announce how far we’d gotten which was a long ways. You know, something like $4 trillion worth of endowments and portfolios have divested from part or whole from fossil fuel. There's people in this room who have played a big role in making that happen. But one of the reasons that there were an enormous array of cameras on hand to do it, was that instead of having me announce this news we asked Leo if he might come do it, and he did. So his abstinent or not, his charisma is fully intact and to watch it, to watch his charisma being weaponized in the service of climate change is a very useful thing. So we’re grateful to him.

Greg Dalton: That was an April Fools. Give thanks to them for that lightning round.

[Applause]

The stock prices of oil companies are based on burning and selling the oil, coal and natural gas in their reserves. That has some investors worried that those stocks could take a dive if world governments hit the brakes on burning fossil fuels. Are big oil boardrooms ready for the potential changes ahead? Anne Simpson is Investment Director of Sustainability at CalPERS, California’s massive public pension fund. She says in order to best serve their investors, the CEOs of oil companies need to stay focused on the big picture.

[END CLIMATE ONE MINUTE]

Greg Dalton: Bill McKibben, I want to ask you what you would say to Kenneth Bone, the gentleman who stood up in the red sweater works at a fossil fuel plant. What do you say to workers, under the anger in this country is some fear about their jobs and it's real for people in the fossil fuel industry.

Bill McKibben: Sure. And, you know, the coal industry is the perfect example. This is an industry that lost most of its labor force over the last 30 years, less because of environmental restraint that because the industry figured out how to mechanize everything that it did. As it shed workers it also pulled off one of the grandest heists of the pension system that we've ever seen and left people without retirement income. One understands why people are upset. The good news is that it's that not only can we create three or four times the number of jobs building renewable energy which is labor-intensive instead of being capital-intensive like the fossil fuel industry but many of the jobs track pretty well with existing fossil fuel industry jobs.

There was a study from the University of Michigan this summer that looked at this exact question. How would you retrain people from the coal fields to work in solar energy? What job, how much and very little retraining have to be done. Many of the skills map very easily and the jobs are of comparable pay. It obviously takes engaged policy leaders, political leaders to make that happen because these are not people who should have to pay this price. And one hopes that this is a place where Hillary Clinton will do some serious work. She said that she will.

On the other hand it's also plain and obvious that it would be ridiculous policy to continue overheating the planet just to keep the small fraction of people who work in the fossil fuel industry working at the same job going forward. That wouldn't make sense on any count, including economically.

Greg Dalton: Let’s go to our audience questions. Welcome.

Male Participant: Okay. So when we manufacture plastic we use a lot of fossil fuels. Would it help if we had more bag bans?

Terry Tamminen: Well, okay.

Greg Dalton: Terry Tamminen.

Terry Tamminen: My wife is sitting right next to you. Leslie Tamminen, and I’m going to give her a big shout out. She got the single-use plastic bag ban in the state of California passed.

[Applause]

And many other states, cities, counties are doing it. But unfortunately the American Chemistry Council backed by the oil industry is spending millions and millions of dollars to put a ballot measure on the California ballot and to confuse people and to try to overturn that. So just a quick plug, we have to vote no on Prop 65, yes on Prop 67.

[Applause]

Greg Dalton: We’re talking about climate change with Terry Tamminen and Bill McKibben. Let’s go to our next young audience question.

Male Participant: Okay speaking of plastic. I mean how much of, I know that plastics are made out of petroleum but like how much of petroleum like petroleum that’s extracted is used to make plastic of any type?

Greg Dalton: Terry Tamminen -- Bill McKibben.

Bill McKibben: It’s a fairly small amount a few percent. And it’s, one of the problems with climate change is that it’s such an overwhelming problem that you end up triaging a certain number of other environmental issues that we should be thinking about a lot. The need to keep the planet from heating up is so great that people have tended to focus there. I'm glad that there are people still at work on things like that bag ban.

Terry Tamminen: A quick answer though to that because it's relevant to young people that are in school. A lot of schools especially in California have a lot of asphalt and there's absolutely no need for that except for a very powerful asphalt industry because that's actually the waste material of every barrel of oil. So they turn that into that black top that you see, which is useful for streets but doesn't need to be in school playgrounds. You should have green or other permeable surfaces --

Greg Dalton: Tires.

Bill McKibben: Ground up for --

Terry Tamminen: Yeah and school gardens. So tell your principals, tell your school leaders to green the campus and get rid of the asphalt.

Greg Dalton: Next question at Climate One. Welcome.

Male Participant: Thank you. Peter Justin with the Citizens’ Climate Lobby. I want to thank Bill McKibben for changing my life. Thank you.

Male Participant: I really like some more discussion here about the need for the carbon tax in order to execute the COP 21 Paris goals. Thank you.

Greg Dalton: Bill McKibben.

Bill McKibben: Sure. Now the piece I wrote said two things, one that we obviously need a price on carbon. Every economist left right and center for 25 years has said that this is a ridiculous inefficiency in our system. There's no reason that we would let this one pollutant be allowed to just spewed for free into the atmosphere. It would be a big change. I also said in the piece, and I think it's important that we’re well past the point where it can be the only thing that we do. One of the hazards of having and I'm sure Terry thinks about this once in a while too. One of the hazards of having written about this 30 years ago is that there are moments when one has to stop oneself from saying, oh if only you’d listened to me then, you know, because 30 years ago, probably a reasonable price on carbon would have been enough to deflect the trajectory of our economy in a right way.

We’re now well past that point. And so it has to be one part of a struggle along with these, you know, strong support for renewable rollout. A keep it in the ground policy that prevents us from taking out fossil fuel anywhere that we can, so on and so forth. But it's a big part and there's at least, you know, depending on what happens in the elections, there is at least some chance that it will be more in the conversation in the next few years than it has been in the last. So thank you for your work.

Terry Tamminen: And just FYI, there’s a carbon tax on the ballot in the state of Washington right now that would tax various fossil fuels and rebate it to consumers. So it would be revenue neutral.

Greg Dalton: British Columbia has been doing that for years and there's Canada is moving ahead with a national carbon price. Let's go to our next question at Climate One. Welcome.

Female Participant: Hi, I’m Christie Drummond [ph]. I’m a senior at UC Berkeley and I’m also an intern for Betsy Rosenberg. She’s been a radio broadcaster on environment for over 20 years. She’s actually had both of you on her show. And now she’s trying to move radio to on screen production. She wants to challenge the fact that mainstream media, CNN, MSNBC, all of these major news outlets are not talking about climate on an everyday basis when they need to be. And this issue is so urgent and we want to push off deniers offset like Hannity on Fox who are telling us about climate change isn’t happening at the rate that it is. And so we want to ask for your advice on that.

Terry Tamminen: Here’s my quick answer to that is, you know, the deniers at Fox have made it simple and sexy. They’ve said, “Oh you’re going to lose your job it’s not happening, it’s bogus and oh it’s terrible, all these people in the coal mines are going to lose their jobs and you’re going to lose your livelihoods.” They’ve made it very simple. And we try to argue with fact, that’s the first problem. And so we’ve got to try to make this issue sexy.

Bill McKibben: And if you had a kid as a result.

Terry Tamminen: Yeah, what’s the carbon footprint of that? Exactly.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: Speaking of kids. Let’s go to our next audience question. Hello there. Welcome. We’re talking about climate at the Commonwealth Club.

Male Participant: I read about the Rwanda agreement recently. What is the role of hydrofluorocarbons in climate change?

Greg Dalton: Rwanda agreement on cooling.

Bill McKibben: Yes. They had a meeting in Kigali in Rwanda where the countries of the world took fairly strong action to deal with this one class of chemicals called hydrofluorocarbons, HFCs that are used in air-conditioners and things.

This is a follow on to the fight against the destruction of the ozone layer that began in Montréal. It's a good sign. This will prevent perhaps half a degree Celsius of warming in the course of this century. But it reminds us again why it was relatively easy to deal with the ozone layer and relatively hard to deal with most climate change with carbon and methane. These are a very small class of chemicals made by a few companies who have fairly readily available substitutes for which they can make as much money as they were making before.

So the political resistance to getting stuff done wasn't so strong. It makes it clear why the fossil fuel industry has been such the central problem. I mean, we learned this year and it really was we should talk about it more than we do. We learned this year from great investigative reporting that Exxon, our biggest fossil fuel company knew everything there was to know about climate change 35 and 40 years ago.

And systematically misled everybody about it and organized, helped organize all the nonsense, denialism and so on and so forth. That's what we grapple with when we moved to coal and gas and oil that we don't have to worry about with things like HFCs.

Greg Dalton: Let’s go to our next question. Welcome.

Male Participant: Thank you. Barack Obama just passed a law that in the Arctic you cannot use seismic surveys for five years but they can still locate where oil and gas are. What can I do to make more laws like this happen or make even better laws?

Greg Dalton: First, tell us how old are you?

Male Participant: I’m 12.

[Applause]

Bill McKibben: I’ve got a question back. Do you know how to kayak or canoe? Have you ever been in a kayak or canoe?

Male Participant: I have, you know, like I think I kayak once, but I was a lot younger.

Bill McKibben: Okay. So here’s what you gotta learn. You gotta go get good at kayaking, okay.

Male Participant: Okay.

Bill McKibben: The reason that President Obama and others have started to take seriously preventing oil exploration in the Arctic is because great activists in places like Portland and Seattle. When Shell a couple years ago decided they were going to go drill the first big holes in the Arctic. These great activists by their thousands in small watercraft. We called them kayaktivists, appeared to block the way. And it was some of the most amazing images you've ever seen. Shell said later that they were abandoning their Arctic oil drilling because they didn't find as much oil as they'd hoped for. I think, in truth, and I've talked to a number of people in the company. What they found was way more trouble than they bargained for. So if we can keep these movements strong we can I think continue to protect the Arctic.

Terry Tamminen: And a quick addition to that. Months and months ago, before any of you heard about the Dakota Pipeline. There was a 13-year-old girl, a member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe who was trying to get an online petition to get the Army Corps of Engineers to delay giving the permit for that long enough to really consult with the tribes which they had not done. She felt if she could get 5,000 signatures on her change.org petition that she could get their attention and get them to stop. She had 500 and she reached out to us and we had Leonardo DiCaprio tweet about it, and overnight she got 81,000 and they backed off for two weeks long enough for us to hire the lawyers. So great to go out in your kayak but you can also just go online.

Terry Tamminen: Yeah.

[Laughter]

And let us know that you're doing it and we’ll bring Leo's brand to help you.

Greg Dalton: That’s Terry Tamminen, head of the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation. Let's go to the next question at Climate.

Female Participant: Hi, I’m Marty Roach [ph] and I want to thank both of the presenters for all the work that you do. And I have a question for Bill. We have a real sad situation in Washington where the climate movement is fighting itself, and time is of the essence.

Bill McKibben: I don't know that much about what's going on in Washington. I think it’s 732, is the bill. It’s a carbon tax thing. The local, what I know is mostly from the local chapter of 350, some of the people who organized all this kayaktivism. And they’ve been not in support of it because they when people were constructing this legislation they didn't consult and get the buy in from communities of color and front-line communities in Washington. The environmental movement suffered for a very long time from being a white and somewhat arrogant operation. We've got to work all over the world in relatively short order and to me unity across movements, across the movement is absolutely essential thing for making that happen.

So my advice to everybody always is get everybody that you can on board. The days when this was going to be done by a some small elite someplace are over and it's time for real, inclusive environmentalism. And especially since the great leaders of this fight for the, you know, I mean we work globally at 350, which means that most of the people that we work with around the world are poor, black, brown, Asian, young, because that's what mostly the world consists of. And that's who, you know, that's who's got to be in the room all the time.

Greg Dalton: Let’s go to our next question at Climate One at the Commonwealth Club.

Female Participant: What can I do to help with these problems?

Bill McKibben: Okay. Can I take a crack at this because I think it’s a key question and almost phrased just almost exactly right. I wrote a piece about this a couple of weeks ago. So most common question, as an individual you know that there's lots of things that are useful to do. Ride your bike instead of being in the car, use solar power, you know, have the right lightbulb. So lots of things as individuals that we can do and I bet you're doing some and I'm doing some. I mean my house is covered with solar panels. I have, you know, drove the first electric Ford in my state. But I don't try to fool myself in the end that this is how we’re going to solve the climate crisis. It's too big and happening too fast and it’s rooted in structural and system issues, okay. That have to do with the power of the fossil fuel industry.

So I guess what I'm trying to say is if you're thinking what can I do, the most important thing you can do is not being I but part of a larger we, okay. To come together in movements. Now the movements that we build at places like 350.org are mostly run by young people all over the world. People your age and just a little bit older who are organizing entire countries and, you know, cities and towns to get things done. So my advice is look for other people, band together and make change on that scale. And if you got some time left over, then make sure you're pestering your parents to get all the right light bulbs, you know, in place.

[Applause]

Greg Dalton: We’ve had other social scientists here at Climate One at the Commonwealth Club who would answer that by saying talk about it. They think there’s a social taboo or silence around climate. People don't bring it up because it's either political, controversial or a downer. So I would add from others talk about it. Let’s go to our next question. Welcome.

Female Participant: So I’m a student at the University of San Francisco and I started a food recovery and donation program to fight food waste. And so I talk to a lot of students about food waste and climate change and I’m just wondering what behaviors do we need to change like as individuals, she kind of asked my question, and as a population to fight this. Because our behaviors are the root cause to all of our social disorder so what do we do?

Greg Dalton: Terry Tamminen.

Terry Tamminen: Let me answer that just one sort of a personal way. In the last 10 years, the average American has gained 10 pounds, myself included. So it turns out that the airlines flying across our country burned 350 million more gallons of jet fuel every year as a result of that extra weight. So if all of us went on a diet and lost that weight, it would be good for us and the planet and it would stop a lot of the food waste because a lot of it has to do with our eating habits. And as you know, in both the developed and the developing world almost half of the food produced is wasted. And a lot of folks are starting to focus on that, with solutions that we probably don't have time for here today. But it's great that you're working on that, especially to make sure that some of what would've been wasted is actually consumed as food.

Greg Dalton: Let’s go to our next question for Terry Tamminen and Bill McKibben.

Male Participant: I’m Charlie Pebore [ph] and I read the young readers edition of “The Omnivore’s Dilemma.” And Michael Pollan briefly mentions climate change, the impact that importing and exporting food has on climate change. Would eating locally bring down climate change and help us with this problem?

Bill McKibben: Well local food is one of the most beautiful movements that sprung up in this country in recent years for all kinds of reasons. That’s one of them, you save some carbon by not moving things around. But you also allow local farmers to do good farming, which often has real benefits for soil and everything else. We’re moving towards a world and you will see it in your lifetime when localization of things, all things becomes much, much more prominent. It's going to be a much more interesting and local place. The only question is can we do it fast enough and thoroughly enough to catch up with climate change before the friction from that climate change overwhelms us. Let's hope so. And having you guys here is a good reminder about why we need to move fast.

Greg Dalton: We have to wrap it up there. We’ve been talking with Terry Tamminen, former chief advisor of Governor Schwarzenegger and head of the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation. And Bill McKibben, cofounder of the activist organization 350.org and author. I'm Greg Dalton. I’d like to think our sold-out audience in the room at the Commonwealth Club and these young students and people listening on air and online. Thank you all for joining us today.

[Applause]

[End]