What If We Get It Right?

Guests

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson

Bill McKibben

Abigail Dillen

Summary

In the face of increasingly frequent fossil fueled disasters, it’s easy to feel hopeless about the future of the climate. But marine biologist, and co-founder of The All We Can Save Project, Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson asks us instead to focus on the question, “What if we get it right?” That also happens to be the title of Johnson’s new book. Johnson says that climate leaders need to help people imagine what a greener world can look like.

“We can easily picture the climate change fueled fires, floods, droughts, and storms, and the immense suffering, all of which are now well underway. However, when it comes to better outcomes, we've largely been left hanging,” says Johnson.

It’s more helpful, she says, to focus on finding joy in climate action: “I think it's important to allow that to be small things, not like a constant skipping giddiness, but like appreciating beauty and love and all of it whenever it appears.”

Johnson credits her parents for her optimism. She tells the story of her father who moved from Jamaica to New York to become an architect. For much of Ayana Elizabeth Johnson’s life, she thought her father was a failure. But an encounter with a black architect younger than her father made her change the way she thought about him, “This man informed me that my father had indeed paved the way and opened doors just as he had intended. My tears of relief welled up. My dad had achieved his ultimate goal.”

The point, she adds, is that one never knows the impact your actions may have on others, years later.

To help her readers find their own sweet spot for climate action, Johnson’s book includes a Venn diagram. Three intersecting circles ask the questions: What are you good at? What needs doing? And what brings you joy? At the intersection is your personal climate action.

Johnson says that there is so much that needs doing, but “if you pick something you're really good at but makes you miserable, A, no one's going to want to collaborate with you… and you'll probably burn out.”

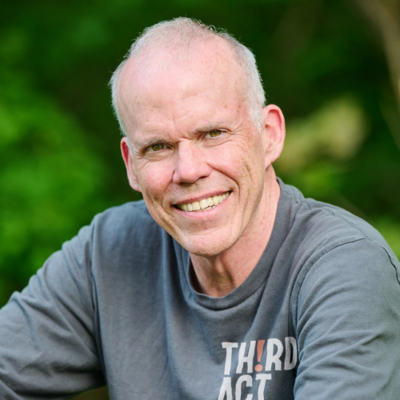

Bill McKibben has written several influential books and co-founded the international grassroots climate organization 350.org. More recently, he started Third Act, which activates seniors in the climate movement: you may have heard of “the rocking chair rebellion.” But long before any of that, back in 1989, McKibben wrote a book called “The End of Nature.” It was the first big, mainstream book on climate change. Despite the warning, we burned fossil fuels at unprecedented levels. “We've put more CO2 in the atmosphere since 1989 than in all of human history before,” says McKibben.

Even though climate trend lines are dire, we have made some amazing progress. “We live on a planet where the cheapest way to make power is to point a sheet of glass at the sun,” says McKibben. He also recognizes that people his age have the power to affect change, “If you have reached the age where you have hair coming out your ears, you probably have structural power.”

You’ve probably heard the tagline: “Because the earth needs a good lawyer.”

It belongs to Earthjustice — a nonprofit law firm that goes to court against powerful polluters and litigates on behalf of the natural world. Their President is Abigail Dillen. She says that legal pillars of environmental protection - like the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act - are under existential threat because of the current Supreme Court. Dillen says, “Never in my lifetime have we seen a court make so many big moves that fundamentally change the fabric of our society.”

And yet, Dillen finds hope in human nature. She says, “We organize ourselves in some profound ways to help each other… Because we have to.”

What Can I Do?

Resources From This Episode (4)

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: I’m Greg Dalton.

Ariana Brocious: And I’m Ariana Brocious.

Greg Dalton: And this is Climate One.

[music change]

Greg Dalton: I’ve been reporting on climate for more than 17 years. And I’ll be honest: a lot of the trends are bleak. The terrible forecasts from scientists are coming true - faster than they predicted - and extreme weather is getting worse.

Ariana Brocious: …and it’s getting a lot more frequent….

Greg Dalton: Exactly… and in the face of all this evidence and suffering, we’re making only some of the changes that are so urgently needed to turn this around.

Ariana Brocious: Right I hear that. And I see it. But one thing you and I both talk about is that – In spite of how dire it feels right now, and it really does it can really feel depressing. There’s so much innovation and possibility and transformation that is possible simultaneously and there’s a lot we can do if we can just kind of get moving. And that’s the subject of a new book called “What if We Get it Right?” It’s by Ayana Elizabeth Johnson – who’s kind of a rockstar in the climate space.

Greg Dalton: Right, she’s a marine biologist and conservation strategist. She is co-founder of the All We Can Save project. And a couple years ago, we at Climate One presented her with the Stephen Schneider Award for outstanding communication of climate science.

Ariana Brocious: And one of the things you can sense across her work is her passion for the natural world and all of us living in it!

I recently had the pleasure of speaking with Johnson in front of a live audience at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco. She told me about a recent trip to the Arctic – a place of incredible beauty… where you can also see the impact of climate change in really stark ways. I asked her how she balances her love for nature while also recognizing our role in its destruction.

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: The gift is that there can be endless beauty amidst the chaos and destruction. And some of that beauty comes from how we, um, look out for each other. The way we care for each other is like, so heartwarming can be. Um, and walruses, have you ever seen a walrus? In the wild? They’re so ridiculous! Um, and it was just, you know, such a treat to be there. And then of course, you're looking at this ice and the colors of the blues, the turquoise, that like royal blue. I've never seen anything like that, even in the Caribbean. Um, but then you're looking at, you know, these glaciers and the guide says, Oh, those used to connect and now they're two miles apart. Right. I mean, the Arctic could be ice free within a decade in the summers, just a completely different ecosystem, right? And currents will change and food webs will change and all of this. Um, and so obviously change is the constant and just embracing that. I mean, I think yeah. I'm known for advocating for finding joy in climate action. And I think it's important to allow that to be small things, not like a constant skipping giddiness, but like appreciating beauty and love and all of it whenever it appears.

Ariana Brocious: Yes, absolutely. Um, well you fell in love with coral reefs at age five.

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: I love a love segue.

Ariana Brocious: and you, you put in your book that it's just as, as coral reefs were dying, but perhaps the same could be said of a five year old today because they're still dying. Um, so there's this term shifting baselines that kind of captures that what we experience as normal or, or static really isn't. Things change, and then we kind of come to think that they aren't what they used to be and so forth. I'm not explaining it that well.

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: This term was coined by Professor Daniel Pauly, the most cited fisheries biologist in the world. Someone I really, really look up to. And yes, it's this idea that whatever, you know, You first saw an ecosystem as you assume that's the baseline, even though it probably was much more resplendent in the past. And so basically we have like lowered expectations

Ariana Brocious: you spend a lot of time studying the oceans and they have absorbed a tremendous amount of the carbon we've emitted. Yeah. And excess heat that we've generated.

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: Over 90%.

Ariana Brocious: By burning fossil fuels.

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: Yeah, the Earth would be like 97 degrees hotter, Fahrenheit, if it weren't for the ocean absorbing

Ariana Brocious: which is remarkable

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: And thank you, ocean, but also, so sorry. Yeah.

Ariana Brocious: And I was reading recently that the house science committee is working on draft legislation to guide research into technologies to pull carbon from the ocean. I wasn't even aware. This was news to me. I wasn't aware that we could do that, that that's like a technology is. Oh, well, there we go. So my question is, what do you think? I mean, we know we can remove carbon from the atmosphere and there's a lot of technology and efforts underway for that. But this is about removing carbon dioxide from the ocean.

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: I don't know. I mean, I think it's very important to say we don't know when we don't know. And I just, I don't know what the technology is. I have no concept of like what the side effects of that would be for carbon capture. From the air. I mean, it's not really happening at a large scale. A lot of people are thinking about it as like a get out of jail free card, right, where you can just keep burning all the fossil fuels you want, and then somehow magically suck all that excess carbon out of the air and just doesn't work that way. It takes a lot of energy to run these carbon removal systems. Kate Marvel, um, NASA climate scientist, and I talked about this in the first interview in the book, and she's like, that can be used to suck out the stuff that's already there, but not as an excuse to just keep emitting. That will never, the physics of that will never make sense.

Ariana Brocious: in your book, you write really beautifully about, um, your parents and you tell the story of your black father who moved to New York from Jamaica to go to college and become an architect. Um, and you say that it wasn't until after he passed away that you understood the nature of his success in his field. Um, can you tell us that story?

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: Well, I didn't think he had any success because he didn't have any fancy buildings he could point to and claim credit for. And maybe I could just read the sentences because I chose the words so carefully. I don't want to, um, botch it. “Every day of my childhood, he would get up Sisyphean, put on a sharp suit, buy a newspaper and a pack of double mint gum, take the subway into Manhattan and try to make headway as a black man in this notoriously insular and racist field. I'm ashamed to admit that I thought he was a failure. He didn't have fancy buildings to point to and claim he never made any money to speak of. It wasn't until a few years ago, after he had passed away, that I was disabused of that perception when I happened to meet a black architect, a generation his junior, at a cocktail party. This man knew of my dad's architecture firm, which is one of the first black owned firms in New York City. With glints of respect and gratitude, this man informed me that my father had indeed paved the way and opened doors just as he had intended. My tears of relief welled up. My dad had achieved his ultimate goal. I tell you this in part because I am proud. But really, I tell you this because I had missed the entire freaking point. It's not about the glory. It's about the ripples. This is what progress often looks like success without rewards.”

Ariana Brocious: How does that shape your approach to the climate change work that you do?

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: I mean, I think the best gift my parents have given me is to just, like, absolutely keep my ego in check. my mother is like, not one for handing out participation trophies, right? and neither my father, I mean, the number of compliments I got from him is sort of a joke, like, good job, kid. I would get that like four times a year and I'd be like, yes. And I think the way that that manifests is they didn't have any particular ambition on my behalf. All they said to me was, you have to give back. You've had all of these opportunities. I had scholarships to all the best schools. You have to, to whom much is given, much is expected. You can do, there are innumerable ways to give back, just choose something. Um, and also that like you're not a savior, like you can help, but there's no expectation that I'm going to like save the world. Right. And, and sort of that combination of low expectations for impact, but high expectations for effort and commitment and values, I think was a really helpful match. But my mother was very much like the world needs more black scientists. So she did encourage me in that direction. But, you know, also being half Jamaican, thinking about the ways in which, um, the degradation of the ocean is a cultural issue. Um, and so I think about climate and environmental issues very much as, um, harmful to coastal communities and cultures, not just economies and safety and health.

Ariana Brocious: Right? Right. You write that 70% of Americans are worried about climate change. Most don't even talk about it with their friends and family, though. Um, and the 11% of Americans, 37 million people who are willing to become actively engaged, haven't taken action. That's a big number of people. And climate can feel lots of things, right? It can feel daunting, overwhelming, scary, um, but you've created a Venn diagram to help people understand where they can find their climate action. And this speaks to what you were just talking about. Um, so for those who are not in the room with us, can you describe the, these three overlapping circles and, you know, how they work?

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: Um, I love a Venn diagram. Um, so the first circle is, what are you good at? So what are your skills, your resources, your networks? What can you specifically bring to the table? And this Is a reaction essentially to the environmental movement from my perspective for many years, giving everyone a very similar and generic list of things we should all do, right? Vote, protest, donate, spread the word, lower your own carbon footprint, which is, of course, you know, a term popularized by Ogilvy on behalf of BP. So thanks. And what a, what a loss if we're all just doing the same things. Please do those things, by the way, like I do them. We should all be doing them. And yet we need to bring our special magic, our superpowers into the mix too. Um, so what are you good at? And I think it's worth saying we should be very generous with ourselves about that category. Like, are you really good at planning parties? That would be helpful. Do you make good websites? We need those. Are you just like an incredible project manager? Great. We need that too. This is not about like engineering per se, right? Or only politics. So what work needs doing? There are hundreds, if not millions of climate and justice solutions. So, um, I recommend people check out Project Drawdown for a list if you need some inspiration. So drawdown.org has all these different climate solutions, their relative, um, you know, benefits on reducing greenhouse gas emissions, et cetera. Um, and then on top of that, the Drawdown review, which came after that, you can download for free on their website and is, I think, much better and clearer. Really good graphic design. I'm obsessed with good design. Um, and it talks about the accelerators for climate, so implementing climate solutions, right? Things like politics and culture. Um, So what work needs doing? Pick something. And then the third circle is what brings you joy. So as we were talking about before, these sources of satisfaction and delight, not this very superficial in my estimation, American pursuit of happiness. I just don't care if we're happy all the time, as long as we're being useful and kind and all these other things.

Ariana Brocious: And joy is different than happiness.

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: It's totally different. And I would say like, if everyone could just be slightly goofier, I'd really appreciate that too. I think this whole book tour, I'm like, can we take climate change seriously, but like, please don't take ourselves seriously. Like, it's just, it's so boring. So that's my pitch. Take it. Take it or leave it. But what brings you joy? And so finding our way to our own sort of bespoke, um, climate action in the heart of those three circles is what I would encourage each of us to do.

Ariana Brocious: I think it's really powerful because it really does that mean the intersection of these things is what also will keep you engaged,

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: Yeah, if you pick something you're really good at but makes you miserable, A, no one's going to want to collaborate with you, and we need to build a bigger, stronger team, and you'll probably burn out. And, you know, this is the work of our lifetimes, so please don't pick something awful to do.

Ariana Brocious: And there's plenty of work doing, needing done, right? Um, you say that this question, what if we get it right, isn't asked enough, um, why isn't it asked more? And, and what's sort of the importance in asking it?

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: Um, I don't know why it's not asked more. This is like a like human psychology question. Maybe we gravitate towards the

Ariana Brocious: I think that's true.

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: I don't know. I don't know if there's any

Ariana Brocious: to envision a dark future.

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: Um, I think I think I'm just going to cheat and answer this the way I answered it in the book, if that's okay. Um, “I would say here, um, if we're honest, maybe we doubt that humanity actually can get it together, can rally the depth of motivation and creativity required to face this unprecedentedly gargantuan challenge. But one thing is certain, um, Half assed action in the face of potential doom is an indisputably absurd choice, especially given that we already have most of the climate solutions we need, heaps of them. Moving forward requires that we propel each other, propel our species, out of a phenomenally entrenched procrastination. We don't need more data or a more rigorous cost benefit analysis. We need action. But I get it. For decades, what scientists, writers, filmmakers, and artists have projected for us is the apocalypse in great detail. We can easily picture the climate change fueled fires, floods, droughts, and storms, and the immense suffering, all of which are now well underway. However, when it comes to better outcomes, we've largely been left hanging. That is a problem. Humans evolved to not leap into a void. That's dangerous. So we need something firm to aim for something with love and joy in it. And we need the gumption that emerges from an effervescent sense of possibility.”

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: So essentially, like, I wrote this book because it's the book I needed to read, right? Like, show me the way forward. And I came up with this title, “What if we get it right? visions of climate futures.” And I was like, Oh, how do I answer this question? Who am I, you know, to answer a question this enormous and fundamental. And so then I, you know, called all my smartest friends to help me answer it. And instead of paraphrasing them, I let them all speak for themselves.

Greg Dalton: That’s Ayana Elizabeth Johnson – her new book is called “What If We Get It Right” and it features conversations with several of those “smart friends” she mentioned. One of them is Bill McKibben:

Bill McKibben: Chase, Citi, Wells Fargo and Bank of America continue to hand out loans even though the scientific community has been absolutely clear that we cannot build more fossil fuel infrastructure.

Greg Dalton: He’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Ariana Brocious: If this conversation resonates with you, don’t keep it to yourself. You can help others find our show by leaving us a review or rating. Or better yet, recommend a specific episode you like to one of your friends. Thanks for your support!

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton.

In a moment, we’re going to get back to Ariana’s conversation with Ayana Elizabeth Johnson. They spoke on stage at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco…

They were joined by climate legend Bill McKibben. He’s written several influential books and co-founded the international grassroots climate organization 350.org. More recently, he started Third Act, which activates seniors in the climate movement:

Ariana recently spoke with Ayana Elizabeth Johnson on stage at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco. They were joined by two of the people featured in Johnson’s new book, “What If We Get It Right?” First: climate legend Bill McKibben. He’s written several influential books and co-founded the international grassroots climate organization 350.org. More recently, he started Third Act, which activates seniors in the climate movement.

But long before any of that, back in 1989, McKibben wrote a book called “The End of Nature.” It was the first big, mainstream book on climate change. And it raised an alarm.

Bill McKibben: In 1989, we had, I mean, the horror, actually, of this story is, we had fair warning. We knew what was coming. The scientific process worked to provide us with a clear consensus picture of what was going to unfold if we didn't stop burning coal and oil and gas. We didn't stop burning coal and oil and gas. We've put more CO2 in the atmosphere since 1989 than in all of human history before. And so now, uh, one has the, the completely unhappy, uh, uh, moment of everything that we warned about starting to happen. In fact, more than starting everything breaking over our heads. I mean, we're sitting here a few days after a hurricane in a rainstorm that left vast corner of this country wrecked, um, just turned upside down and not for the first time, for the 100th time. And that's just this country.

Ariana Brocious: It was accelerated right by warmer oceans

Bill McKibben: Absolutely. I mean, we're now living in, the last 18 months have seen a rapid spike in the planet's temperature, which had been ramping steadily up. But we've had the hottest days on this earth in 125,000 years, which means all of us are living on a hotter planet than anyone we would really ever recognize as a fellow human has ever lived on, and the results are miserable as one would expect. And the prospect, of course, is that it will get much worse before it gets better. That's how the physics of this is going to play out. But that's precisely why the message of this book is so important. We have, and this is the key part always to remember, a few years to make very, very dramatic changes, the biggest changes humans have made in how they organize their economies in hundreds of years, and if we don't do it, this will get much, much worse, but It's entirely possible to do it. We have, as Ayana says, the tools that we need. We can begin to see them starting to be deployed. The question is whether or not we will do it at a pace that begins to catch up with the physics of climate change. And that in turn depends on, I think, at least in part, some of those questions of psychology that Ayana keeps discussing.

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: How quickly and how justly right there's different possible futures, but we just further entrench inequality and that's no good.

Bill McKibben: Absolutely. Um, so far we've run this climate movement, which we've both played our part to help build on mostly fear and anxiety and guilt and sadness, all of which are entirely appropriate emotions and all of which have had their power. Thank you. But we've probably maxed out the number of people that we can get with those and they've begun to cause often a kind of paralyzing grief and anxiety. So now we need to draw on other emotions, hope and joy and a sense of adventure, um, which are very real. So we're, we're, you know, California where we are, In the last year, Has finally in an advance of almost any place on the planet installed enough solar panels and enough batteries that for the last 100 days, California has produced more than 100 percent of the electricity that it uses every day from renewable resources. That's a first when the sun goes down at night, the biggest source of supply to the California grid is batteries that did not exist on that grid three years ago. 2024. Compared to 2023, California has used 29 percent less natural gas to generate electricity than it did last year, 29 percent a big number, a number big enough that spread around the world, that takes a big chunk, starts to take a chunk out of the three degrees Celsius that we're staring in the face of. But, but It has to happen, this change, very fast. Because if it doesn't happen fast, then it doesn't do us much good. No one has a plan for how to freeze the Arctic back up again once it's melted.

Ariana Brocious: Right. Well, I'm sure there will be plans for that.

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: And they’ll probably come from sort of near here, won’t they?

Ariana Brocious: It’s possible! Bill, you've spent a number of years or maybe really the last decade focused on money and you and Naomi Klein and others spurred a fossil fuel divestment campaign beginning in 2012. About 40 trillion dollars. I think I have that number right in university endowment funds and pension funds have since been pulled out of fossil fuels. That's a huge number. And fossil fuels continue to be, you know, um, mined or, um, pumped and drilled and, and used and burned. So what evidence do you have that divestment is having an effect?

Bill McKibben: Well, I mean, we've slowed down. We've made it more expensive to do this work, and there's, the coal industry can't really find much capital anymore to expand, but the oil and gas industry continues to find capital in part because the biggest banks in the world and the four biggest funders of fossil fuel on the planet are Chase City, Wells Fargo and Bank of America continue to hand out loans even though the scientific community has been absolutely clear that we cannot build more fossil fuel infrastructure.

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: you told me, um, JP Morgan Chase, Citibank, Wells Fargo and Bank of America provided about 1.5 trillion dollars in financing to fossil fuel companies since the Paris agreement was signed, where we all agreed we should ramp down those things.

Bill McKibben: And that number's just kept going up, which is why, you know, a thousand of us went to jail this summer outside Citibank in New York. it's unconscionable what, uh, institutions in the name of the most short sighted, short term greed are doing. Are willing to do, they will break the planet if we don't manage to stop this quickly.

Ariana Brocious: And are you seeing, uh, there was one bank you wrote about in the interview with Ayana in here that did make a marked change, but those four haven't to my knowledge.

Bill McKibben: So I mean, are you seeing they're starting to make. I mean, actually, The craziest part of it is, is that they've all made some noises, you know? Um, oh, we're going to go net zero or whatever. We'll do it someday, we'll, you know. But nobody is willing to just, uh, uh, bite the bullet and get down to it, which is quite annoying, because, you know,

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: To put it mildly

Bill McKibben: uh, I mean, one understands why, uh, Exxon is, uh, you know, are, are amoral, uh, actors. They know how to do one thing in the world, drill for oil and set it on fire. But, you know, Chase Bank, this is a relatively small part of their business. They can make outsized profits doing lots of other things, including the thing that we actually need to do on this planet. Which is deploy lots of capital to build solar panels, wind turbines, and batteries as fast as ever we can.

Ariana Brocious: Well, what's holding them back is it, is it

Bill McKibben: The CEO of Exxon said earlier this year that his company would never invest in renewables because they don't return above average profits for our shareholders. And in that he's correct. In that, um, you can't, you can make plenty of money putting up solar panels, but you can't make Exxon sized money. And the reason is because once you've put them up, then the sun delivers the energy for free every morning when it rises above the horizon. You know, Exxon can't control the sun's output and store it up and sell it to us a little bit at a time. It's a, uh, It's a great gift from the world around us that we can take advantage of, and that's spectacular news for humanity. Uh, we're at the moment when if we could seize it, we could stop burning things on planet Earth in short order. Not only might save the climate, but nine million people a year. One death in five on this planet comes from breathing the particulates that go and you burn fossil fuel, which we do not need to do anymore. We live on a planet where the cheapest way to make power is to point a sheet of glass at the sun. Okay, um, that we continue to do that is down mostly, really entirely to the fact that the small number of people who own oil wells and coal mines refuse to part with their business model and If we can't make them do it, which is why we organize in the ways we do then we have little prospect. But I think we can make them do it, or at least we can give it a good try.

Ariana Brocious: Ayana mentioned your organization Third Act, and I want to get to that. Um, this is aimed at activating folks over 60 in their quote unquote third act of life. For you personally, how has your approach to activism changed, uh, in this phase of life?

Bill McKibben: Well, I mean, I, I've been at this a while, since I wrote The End of Nature when I was in my mid twenties. So, I'm now in my mid sixties. So, I, it's been a lifetime's work. Um, And the, the, the motivations shift some. Um, you know, I'm gonna be dead before the very worst of this hits. Uh, so it's not anymore quite myself I'm thinking about, but as you get nearer the exit than the entrance. Um, terms like legacy start to become less abstract. I mean, legacy is the world you leave behind for the people you love the most. We're about to be the first generations to leave behind a planet worse than the one we inherited, which no one wants. Uh, you know, I, I have a, now a six month old grandchild. And that means I'm deeply in love with someone who's going to be here in the 22nd century. God willing. And, and, so that does shift how one thinks about time and the future.

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: There’s actually, um, new polling on specifically this motivation that says when advocating for climate action, love for protecting future generations is the biggest motivator, 12 times more popular than job creation or economic growth, which is great that people aren't just motivated by money and sort of like the as these executives are, but not the average person. Um, but I think. I used to think that I was kind of corny, like do it for love kind of thing. It's like, so, I mean, I'm like

Bill McKibben: You're a romantic, come on.

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: but I think of like climate action as like, just, of course, we're going to try to make this better. Right. Like you don't have to get all romantic about it, but, and especially as someone without children, like it's not something that I always thought of as like my personal legacy. But I certainly do think about in terms of biophilia, right? Like my love of life and biodiversity. And of course, like, even though I don't have my own children, I love children. I would like them to live in a safe and healthy world. Um, and so I think this is another thing that the climate movement hasn't really tapped into is, um, apart from joy, uh, and adventure. And I would add creativity as exciting reasons to be involved in this, that like, we should just embrace that. do this for love.

Ariana Brocious: And I also want to say that to me, third act, people who are in that phase of life have money and power and time. And in my mind, those are things you need to be deeply engaged, and maybe you don't have to have those. And it's not a prerequisite. But I want to think that, you know, influence to people who are, who have had careers and maybe have ties. I mean, are you seeing that work?

Bill McKibben: we say, if you're looking, if you um, If you have reached the age where you have hair coming out your ears, you, you probably have structural power coming

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: out of your ears. I can vouch for the ear hair since I'm on

Bill McKibben: we're, uh, uh, there's 70 million, 70 million Americans over the age of 60, 10,000 more every day, which is more than the number of people born in this country every day. Uh, we punch above our weight politically. Because we all vote, there is no known way to stop old people from voting. And we ended up with most of the resources. So if you want to put some pressure on Washington or Wall Street or your state capital, having a few people with hairlines like mine, I mean, you know, we'd all love to have a hairline like Ayana's. You know, let's be honest. But, It's not the worst thing in the world to have some older people backing up the young people doing this work. The first time we did one of these demonstrations outside a bank, it was because young people had asked us to come join in. And they were like, we, we want to protest outside Chase, but we don't even have checking accounts. So will you come? We're like, sure. And, and, uh, we showed up and there were, you know, two people. Two or three hundred high school kids because there always are. They understand perfectly well the barrel down which they are staring. Um, and they're somewhat spryer. So they were in the lead of the march. But at the back there was a group of us from this nascent third act with a big banner that said, Fossils against fossil fuels. And we've gone on. Now we've got a hundred thousand volunteers around the country. Uh, uh, Uh, we're good at this stuff in all kinds of ways, from getting people to vote to getting people to go to jail, and,

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: they'll show up with their rocking chairs and give you the stink eye.

Bill McKibben: We're a little, uh, we've reached the age when sprawling on the concrete outside Citibank for four or five hours at a time is less fun than you would once would have been. So, that's right, we went to Goodwill, we got every rocking chair we could find. The Times the next day called it the Rocking Chair

Ariana Brocious: I love that.

Bill McKibben: So, it's, it's symbolic of precisely what Ayana is talking about in that Venn diagram.

Greg Dalton: We’ll have more of Bill McKibben and Ayana Elizabeth Johnson in a moment.

Coming up, it’s not just you, the recent rulings by the Supreme Court really have been seismic.

Abigail Dillen: Never in my lifetime have we seen a court make so many big moves that fundamentally change the fabric of our society.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Ariana Brocious: This is Climate One. I’m Ariana Brocious.

GREG PICKUP:

And I’m Greg Dalton. You’ve probably heard the tagline: “Because the earth needs a good lawyer.” It belongs to Earthjustice – a nonprofit law firm which goes to court against powerful polluters and litigates on behalf of the natural world.

Abigail Dillen is the president of EarthJustice– and Ayana Elizabeth Johnson featured her in the new book “What if We Get it Right.” Recently, they both joined you – along with Bill McKibben – for a special live conversation at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco.

Ariana Brocious: I wanted to talk about the ways the legal system sometimes supports climate progress – and sometimes works against it. For example, back in the 1970s, a bipartisan congress passed a ton of environmental legislation, including the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, the Endangered Species Act.

But now all of those laws are being challenged in the courts. So I asked Abigail Dillen: how much are those pillars of environmental protection under threat?

Abigail Dillen: Existentially. So one thing to remember about that time, which I think the climate movement is just catching up to, is that there was a holistic analysis that we were polluting our air, giving people asthma, cancer, that we were polluting our rivers, they were catching on fire, at least one of them in Ohio. That we were our unbridled chemical industry was threatening the web of life. Rachel Carson made that one of her just incredible contributions was to write Silent Spring, but at some point people stop thinking about the world as a system and as this extractable, static resource. And in the 70s, things got so bad. that you had, whether it was biophilia or just pure survival instinct, even industry was recognizing that we needed to do something about it, or we weren't going to have a country you could really live in. And so President Nixon, with a bipartisan Congress, passes all of these laws that had at their core, a distrust of regulated industry and government to do the right thing because often resources run short or political will does, and so they empowered anyone who's affected. That's everybody in this room were affected in some way to hold the government accountable to stand in the shoes of an attorney general. It's a very, very powerful set of laws that we have in the United States. And they've become a foundation for other countries too. I'm glad to say that lots of laws around the world are now exceeding what we're doing in the U.S. But Congress knew that someone was going to have to sweat the details. They wanted the laws to get stronger as technology evolved. They wanted the laws to get better and better tailored as our scientific understanding evolved. And so they entrusted experts in the federal government to evolve the regulations over time. These are broad sweeping mandates. It says, make the waters run clean, make the air healthy. By the way, the Clean Air Act talked about the atmosphere. It anticipated climate change. Now we have a Supreme Court that says, I don't think Congress could give that expanse of authority and we don't think experts and agencies really ought to make the calls,

Ariana Brocious: Right. So you're referring to this case that came out in 2022

Abigail Dillen: Not just one

Ariana Brocious: The major questions doctrine, the EPA versus West Virginia. Is that the case? You can say more about it. I mean, that essentially said that, right? That, that these agencies are not empowered in the way that they have been for 40 years, 50 years.

Abigail Dillen: Yeah. I mean, so let me say a few things about the last few terms of the Supreme Court. Never in my lifetime have we seen a court make so many big moves that fundamentally change the fabric of our society. Usually the court will make one move and wait 10 or 15 years to see how it plays out. So in the heart of COVID, they made big foray to say, we don't think the president has the ability to deal with a major pandemic as it pertains to workers' health. I've really surprised people in the workers rights community. Then we have this major questions doctrine firmly announced, which is the idea Congress can't make big moves. The courts will decide whether a president can or can't do something when it has vast economic or, or, um, social implications. Well, that's everything our federal government does. This is a judge's decide rule. Remember, the judges that were appointed during the Trump administration, not for their reputation for fairness or civility, not for their legal credentials, for two things, their position on reproductive rights and their position about the role of government. Which is de minimis other than protecting private property rights and corporate interests. So that's the invitation that was given and since then we've had three more blockbusters that are pushing the envelope even further about what the scope of a president's authority do to respond to our activism.

Ariana Brocious: So how does that affect the strategy of you and your peers at Earthjustice? I mean, when the laws that you're using are kind of shifting or the understanding of them is shifting under your feet?

Abigail Dillen: Well, the first thing I want to say is a de-escalation of the alarm I hope you're feeling, um, which is that the Supreme Court only takes so many cases a year. The signal that has been sent to, um, a cadre of ultra conservative lower court judges is tempered by the fact that, uh, during the Biden administration, there's been an enormous number of other kinds of judges appointed. A fair and good judge who respects science and facts is not precluded from doing the right thing. So we're still winning many of our client cases. And judges are people too, and whatever their ideology is, they're living in this crisis that is affecting us all so deeply and so

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: and their children and grandchildren, and

Abigail Dillen: and their children and grandchildren, and so, um, You never know, but we're, we're still winning many of our cases and I, and I think that will continue to be true and there are state courts and there are all kinds of decisions that Third Act is trying to influence in our public utility commissions. We, we lawyer the hell out of everything. Um, and, and a lot of that important work is insulated from this Supreme Court with an agenda. But. I've had to realize that the last 50 years, 52 years of what Earthjustice has done, are going to be different than the next 50. And even though it is not standard practice for a lawyer to criticize the courts, we appear in front of them. We have to tell the truth about what is happening right now, cannot survive this Supreme Court agenda. We cannot. Either this court has to moderate itself to reflect the conditions of our time. Or it must be reformed. And I think that's, um, one of the areas we all have to be activist about.

Ariana Brocious: there's something you write about in your interview with Ayana, the Environmental Justice for All Act. Can you say a bit about what that is? And I invite Ayana and Bill to jump into about the importance of if we were to accomplish getting something like that passed, what it would mean?

Abigail Dillen: Oh, I'm glad you brought up the Environmental Justice for All Act, which is now named after the late Don McEachin, an environmental hero. We are having a correct conversation in the country about how we build our new society faster and there's no question we need to get more transmission. We need to deliver clean power, scale up the solutions and we're working very hard on that. And there are some shortcuts being proposed that we should just stop the enterprise of environmental review, that, that no one should have a say. And my view is, you know, there are some things about, uh, some of these bedrock environmental laws that haven't worked. We've,fortunes in this country, we've built a lot out and we have not shifted who has access to clean air and clean water. Your zip code still defines your future. And so the Environmental Justice for All Act is about making sure that as we build a new country, a new economy, if we get it right. The part of getting it right will be ensuring we don't build in all the old injustices that define our society and and are at the root cause of where we are now. And I'll, I'll just say one sentence on what I mean by that. If we didn't tolerate the conditions in Cancer Alley of the Gulf Coast in this country, if we didn't tolerate the conditions that people live in, in the Ohio River Valley, we wouldn't be the biggest fossil fuels producer in the world. So that's, that's the core of what this crucial act is.

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: Another one of the interviews in this book is with Rihanna Gun Wright, who does incredible work on climate policy, was the one of the lead architects of writing the green New Deal resolution. And she's like, if everyone had to breathe this air. If rich white people had to breathe this air, we would have solved this problem long ago, right? It's the communities that live along the fence lines of these fossil fuel facilities that are dealing with the major burdens, health impacts of all of this. Um, and so yes, we'd all much rather catch photons from the sky than keep doing this crazy setting dinosaur juice on fire thing. Um, and I think that's, it's just, it, it just feels so ridiculous to have to say that out loud. To advocate for justice in that way, because it's just like, of course, we shouldn't be making poor people and people of color deal with all this stuff, especially given the even grosser injustice that often they're the ones that did the least to cause it all over the world.

Ariana Brocious:We've seen some court cases now, um, targeting the oil majors themselves. We've also seen cases of really exciting, like the ones in Montana, um, youth defending their right to a clean environment through the state constitution, which was cool. Um, what is most exciting to you in the cases that you're, even if you're not working on them, that you're seeing out there right now,

Abigail Dillen: Let me give two examples and one overarching excitement. Um, my greatest fear was that as the courts became more hostile, people would say, Well, guess we can't think about the courts anymore. And instead people would say, Oh, we need, we need a rule of law. And so I'm really glad that the courts are getting the attention they deserve and more of that. Two favorite cases, um, I bet everyone listening and who's in the room has heard about Our Children's Trust, uh, incredible young people who are coming forward to vindicate their rights to a future. And, uh, We litigated one of these with our Children's Trust in Hawaii, and I'll never forget calling up one of my best friends at Earthjustice, Isaac Moriwaki, on the days that the Maui fires were raging just to see if he was okay and if, if everyone in our office was okay. And he said, you know, we were just about to go depose the Hawaii Department of Transportation. And that was one of many, many depositions. The state of Hawaii was not like, come on in, we'd love to settle this case. They contested it. But, because Isaac and the people who were litigating this really understood the power map in that state, what the possibilities were, what the problems were. In Hawaii now, the biggest emitters are the transportation section, and everyone had done their homework about what would it look like for the state of Hawaii to stepwise on a responsible schedule, get the transportation problem solved. And the guy who runs the Department of Transportation thought, it was a whole bunch of good ideas and was willing to sit down with our lawyers and hammer out a settlement. It's the first of these cases that's yielded an actual enforceable roadmap. And we, we talk about Hawaii as like postcards from the future. I love this postcard from the future because it's something we can replicate. And so the idea of young people getting to, you know, create the catalytic choice point for a government and for a government of responsible people who felt those fires to stand up and say, yes, let's do this with you. That is so thrilling.

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: Such a big deal.

Abigail Dillen: One more and I'll, I'll go quickly on this one, but we have an incredible attorney general in the state of California, and the lawsuit that attorney general Bonta filed last week against Exxon. I think it's gonna change the world. It's about the lie of plastics recycling that Exxon and others, of course, the fossil fuel industry seeded and what I think it's doing just in that the people versus Exxon, it has been so hard for folks to understand how oil and gas become toxic, cancer causing petrochemicals that are then the feedstocks of plastics, which are making us sick, killing the oceans. It is the whole system. In one thing that we call plastics, and I don't think there's a person in the world, you can feel abstract about energy and where you get your electricity, but none of us feels abstract about plastic. I've been enraged about my dependence on, you know, you can't get away from it. But the fury that I feel now, knowing that I've actually entertained the belief that I could put it in a bin and it wouldn't be as bad as I know it is. Wow. The deception of this industry. And how it has prevented us from making the right choices for so long. It's hitting me all over again

Ariana Brocious: And making it your problem.

Abigail Dillen: and making it my problem

Ariana Brocious: are responsible for recycling, not the producer of the plastic.

Abigail Dillen: yes. And so I,

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: And it's not even possible. I mean, that's the lawsuit is about, like, you can't really recycle most plastic, right? And those numbers with those cute three arrows on the bottom, all that means is what type of plastic it is. It doesn't actually mean it's recyclable, like that is the most offensive greenwashing, right? Um, I just don't know. Go

Abigail Dillen: offensive and most

Ariana Brocious: end. Most offensive in

Abigail Dillen: Yeah, no, but it's thrilling to see state attorney generals with all the extra, you know, we've got 600 folks at Earthjustice. We're just this tiny group of people, even if we feel like we're bigger than we once were. When attorney generals of the fifth biggest economy in the world get going on this, it gives me a lot of hope. And there might be a showdown with the Supreme Court. But it's too late. We now know what the facts are. Read that complaint. It is a page-turner, and I'm serious. I'm a nerd, But

Bill McKibben: This profoundly makes the point that none of this happens. No arm of this happens by itself. So it's always a mix of litigation and legislation and protest and lobbying. I was in Montana over the weekend. And Montana is the other state where young people have managed to win a court victory in this, uh, uh, and the reason they were able to is because Article 9 of the Montana State Constitution guarantees the right to a clean and healthy environment and mandates that the legislature enforce it. It surprises people when they read that Montana, now we think of as quite conservative state, has this provision. It was adopted. In the year or two after Earth Day, when, in 1970, when 20 million Americans were in the street, uh, 10 percent of the then population, the biggest demonstration we've ever had in this country. Lawyers can't do this, you know, produce magic on their own. Uh, all of this requires that we change the zeitgeist of the world in which we live, and that's what organizing is about. That's what this book is about. That's why we engage in this kind of conversation. And, and, sometimes that's why we go to jail. And, and, What Ayana so beautifully managed to do in this book is bring together the fact that there is no exact one magic solution to what we're doing. Uh, uh, it's going to take people who have different skills, different resources, uh, uh, working very much towards the same end. And because. Because the bad guys are working very much towards the same end. Profit is a deeply unifying motive that keeps them hard at work 24 7, uh, uh, doing what they're trying to do. Um, love needs to be our motive and it needs to keep us engaged. as hard at work,

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: You talk a lot about, um, You know, the profit motive. I think there's a corollary to that that I think we don't talk enough about that you brought up in our interview that I think everyone with a law degree brought up in their interview in this. I was like, Oh, this is the unifying thing. Property rights, right? You said when I interviewed you, the common core of all these ideas, right? The Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act is law that recognizes the rights of the collective. We need to move from a system that reifies individual property rights and shifts to not only account for but truly protect the common good of public interest.

Abigail Dillen: It's so fundamental that we don't even perceive it. It almost seems original sometimes to people when you say the one thing that we actually revere is the right to private property. So, if you think about pollution, you have a right to extract. You have a right to pollute. It's just limited. And, You know, that's not going to work at a time where we have water scarcity, we have, uh, uh, atmospheric commons that we just have to protect forever. And, and the Supreme Court case I didn't mention, which just blew a hole in the Clean Water Act is premised on the idea that if there is a private property right in play, Congress really, really, really can't give big authority to the executive agencies like you need an extra clear statement if you want to regulate with any impact on private property rights, that's a very scary test because it basically brings all of our environmental protections into question. They all impact private property.

Ariana Brocious: final question for all of you. Uh, what if we get it right? each of you can have a turn answering. We'll start with you, Bill.

Bill McKibben: Well, let's, let me say what it doesn't mean. We're not stopping. Climate change is not one of the possibilities, and we're going to deal with a lot of grief and a lot of pain on this planet in the decades ahead, no matter what we do. But we could use the transition that we have to make because physics requires it to build a world far more just, far more localized, far more intelligent than the one that we inhabit at the moment. And it would be a good idea to use this thing that we have to do to do the things that we should have done long ago.

Abigail Dillen: I can build on that. You said we've had fair warning and for many of us, even to read Ayana’s book and read the climate science, it is so different to read it now that it's happening as opposed to read it as a future. It's now, it's like the diagnosis that you've gotten and you really want to understand. And there's nothing good about it. There's nothing good about the fact that we've let it go and it's happening. But the only thing that I see changing that gives me some courage is that there's something about the human species. We organize ourselves in some profound ways to help each other. The fact that we have medicine, the fact that we have schools, the fact that we, not well enough, but take care of each other in our old age, that we take care of each other in disasters. We're never going to get people out in the streets by saying, look, another hurricane or another wildfire. But we, what we are doing is starting to spur the thinking about how we're going to protect each other in this new weather. I think that's the best of our species. And so now as we face these climate shocks, that's a nice way to put it really, one after another. Some part of us and I hope it's the critical mass of us is going to engage in what my friend after seeing us speak last night calls love politics. Because we have to, because we have to.

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: Um, so, It's funny, like I get asked this question obviously a lot. I'm on a book tour for a book called What If We Get It Right. So like, tell me, Ayana, what does it mean to get it right? Um, and the last chapter of my book, um, is called Away From the Brink, um, which was going to be the title of the book, but I was told it wasn't cheerful enough.

Ariana Brocious: sure if it would work.

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: actually the original title was What Do We Become, colon, how humans Survive Humanity. That's what I sold the book as titled. Um, but I actually had a lot of fun writing this last chapter, pulling from all these, um, incredible people I interviewed and trying to weave some of their ideas together. And I won't spoil it for you by reading the whole thing, but it's, um, a handful of paragraphs and each starts with a, if we get it right sentence. So I can just share a few of those. “ If we get it right. The world is a lot more green, more full of life. If we get it right, the combustion phase of humanity is over. If we get it right, we have relocalized and we eat well. If we get it right, our homes are comfortable. The future is not drafty. If we get it right, there is no traffic in cities because there are so few cars in cities. If we get it right, coastlines are greener too. Mangroves and wetlands and seagrasses and dune grasses have been replanted. If we get it right, the tyranny of the minority is over. The climate concerned majority rules. If we get it right, there are fewer desk jobs and electricians do very well on dating apps. If we get it right, the pace of life is more humane. We are unrushed, chill even. If we get it right, culture has caught up with our climate reality. Hollywood and celebrities are all in. Climate is the context. Spring is not silent. It's cacophonous. We are putting the pieces back together, adapting to the climate changed world with eyes and hearts wide open. We embrace possibility, continually moving away from the brink and toward answers to the grand question, what if we get it right?”

Ariana Brocious: Bill McKibben, Ayana Elizabeth Johnson and Abigail Dillen. Thank you so much for joining us on Climate One.

Ariana Brocious: And that’s our show. Thanks for listening. Talking about climate can be hard, and exciting and interesting -- AND it’s critical to address the transitions we need to make in all parts of society. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. You can do it right now on your device. Or consider joining us on Patreon and supporting the show that way.

Greg Dalton: Climate One is a production of the Commonwealth Club. Our team includes Brad Marshland, Jenny Park, Ariana Brocious, Austin Colón, Megan Biscieglia, Ben Testani and Jenny Lawton. Our theme music is by George Young. I’m Greg Dalton.