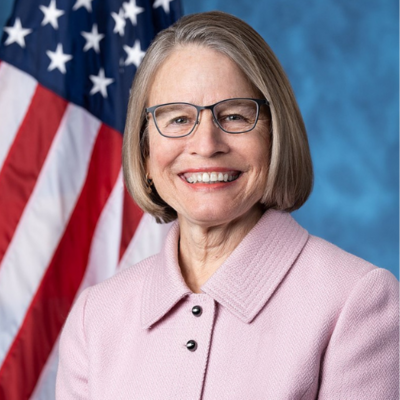

Mary Nichols: A Climate Champion’s Legacy

Guests

Mary Nichols

Summary

Mary Nichols is not a household name, but she arguably has done more than any other public official to reduce America's carbon pollution. As she puts it, “I took on the one topic that everybody agreed was really important, but they didn't know what to do about, and that was air pollution,”

Nichols first served as chair of California's Air Resources Board, or the Air Board, from 1979 to 1983 in Democratic Gov. Jerry Brown's first term. When she returned to the job, almost 25 years later under a Republican governor, the board had evolved into a much more powerful and important player, in what had become an urgent struggle against climate change. The Board played a crucial role, for example, in exposing the Volkswagen “Dieselgate” scandal.

“The Air Resources Board and our engineers are the ones who uncovered the fraud and figured out how it actually worked,” she recalls, “and we immediately brought in the Federal Environmental Protection Agency and in turn, the Department of Justice.”

More recently, Nichols has been busy battling the Trump administration’s attempt to water down California’s fuel economy rules -- which often become national standards because of that state’s big car market.

“It's about the merits, it’s about getting the results and the environmental benefits,” Nichols says, “but it's also about protecting California's right to set standards because that has been time and time again the one tool that we the people as a whole have had to really force progress on the part of the industry.”

Related links:

California Air Resources Board

Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE)

Vehicle Emissions California Waivers and Authorizations

This program was recorded via video on November 17, 2020.

Full Transcript

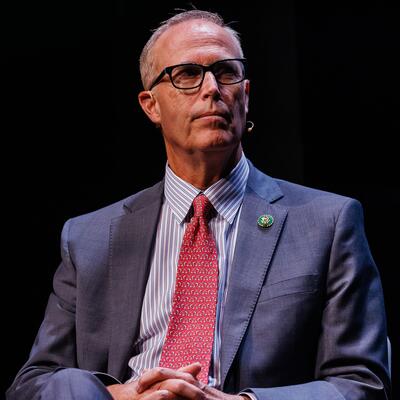

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton.

Arnold Schwarzenegger: When we sign this bill we will begin a bold new era of environmental protection here in California that would change the course of history.

Greg Dalton: California’s AB 32, signed into law by Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger in 2006, is the country’s strongest climate law. One of its top enforcers has been the chair of California's Air Board, Mary Nichols.

Mary Nichols: I took on the one topic that everybody agreed was really important, but they didn't know what to do about, and that was air pollution.

Greg Dalton: Nichols has arguably done more than any (other) public official to reduce America's carbon pollution.

Mary Nichols: I believe that if you have the forces of right on your side and you can appeal to the public, ultimately you will win and I think that's what's happening.

Greg Dalton: Mary Nichols, Climate Champion. Up next on Climate One.

---

Greg Dalton: What is the legacy – and the work still to do – for one of America’s foremost climate champions? Climate One conversations feature all aspects of the climate emergency: the individual and the systemic, the exciting and the scary. I’m Greg Dalton.

Greg Dalton: Mary Nichols is not a household name, but she arguably has done more than any other public official to reduce America's carbon pollution. No wonder Joe Biden is considering tapping her to lead the US EPA.

She's beat oil companies in court, many times, and has crafted detailed air pollution rules adopted by China, Canada and other countries. She first served as chair of California's Air Resources Board, or the Air Board, from 1979 to 1983 in Democratic Gov. Jerry Brown's first term. When she returned to the job, almost 25 years later under a Republican governor, the board had evolved into a much more powerful and important player, in what had become an urgent struggle against climate change. Climate One’s Andrew Stelzer starts us off with highlights of the Air Board’s rise to prominence.

[Start Playback]

Andrew Stelzer: In September of 2006 Republican Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger went against the grain of his party and sign the country's first major law confronting climate change.

Arnold Schwarzenegger: I’m gonna sign this bill where we begin a bold new era of environmental protection here in California that would change the course of history.

Female Speaker: AB 32 or the Global Warming Solutions Act is the country’s strongest climate change law. It aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by 2020.

Arnold Schwarzenegger: We can do this simultaneously. We can make the economy grow and also protect our environment.

Andrew Stelzer: The following year the governor appointed Mary Nichols to head California's Air Resources Board. The agency was given authority to write the rules on an economy wide transition away from fossils. Before they got very far, the subprime mortgage crisis plunged the country into the great recession. The oil industry seized the moment to fight back by putting a measure on the state ballot.

Male Speaker: Two Texas oil companies have a deceptive scheme to take us backwards. They’re spending millions pushing Prop 23 which would kill clean energy standards, keep us addicted to costly polluting oil and threaten hundreds of thousands of California jobs.

Andrew Stelzer: In 2010, voters rejected the ballot initiative strengthening the Air Board’s hand. A few weeks later when climate talks in Copenhagen failed to produce a global agreement, California's progress was a lonely, environmental bright spot. Over the next few years, the board fought up several lawsuits designed to reduce its regulatory power. Then in 2015 the “dieselgate” scandal put the agency on international stage.

Male Speaker: What has VW been up to? Essentially the car company was cheating on the very strict emissions test by getting cars to give false reading.

Andrew Stelzer: Here's Air Board Chair Mary Nichols.

Mary Nichols: The Air Resources Board, and our engineers are the ones who uncovered the fraud and figured out how it actually worked. And we immediately brought in the Federal Environmental Protection Agency and in turn, the Department of Justice.

Male Speaker: Volkswagen reaches a deal to buy back or fix half a million U.S. cars involved in the emissions cheat. The company says the price tag for the crisis is doubled its original estimate. It sets aside about $18 billion to deal with the cost of the scandal.

Andrew Stelzer: Former California State Atty. Gen. Kamala Harris.

Kamala Harris: It is the largest settlement ever with an automaker. It is the largest settlement ever in the context of the Clean Air Act and in the context of enforcement of our environmental laws.

Andrew Stelzer: As part of the settlement, VW created a new $2 billion zero-emission vehicle initiative. The move helped spark EV investment throughout the auto industry. California's Air Board was able to help turn a pollution crisis into progress moving not just California but the entire country towards a lower carbon future. For Climate One, I’m Andrew Stelzer.

[End Playback]

Greg Dalton: I first met Mary Nichols in 2007. Around that time, Gov. Schwarzenegger’s Chief of Staff called her, asking for suggestions to replace the chair of the California Air Board, whom he had just fired. So what did she say on that phone call?

Mary Nichols: It was something like, well, I'd consider doing it myself. I pretty much nominated myself.

Greg Dalton: And why did you become an environmental lawyer, what was sort of your path your inspiration? You had chaired the Air Board, you’re a lawyer. What was your kind of your inspiration and story to becoming the clear path that you set on?

Mary Nichols: Well, I was an activist before I was an environmentalist. I mean, I grew up in a lovely place in upstate New York, Ithaca, New York, and had, you know, experiences hiking and camping, etc. but really the whole issue of the environment as a political issue didn't exist when I was growing up and there was no such thing as an environmentalist really. There was a Sierra Club they’ve been around but they were not particularly big in my part of the world. What tipped it was Earth Day in 1970 and then the rise of a whole new generation of young lawyers and other kinds of organizers and activists who saw the environment as something that was in need of action by the government either to stop bad things from happening or to create better conditions for nature for wildlife, etc. And as someone who had gone to law school inspired by my experiences in the south of the civil rights movement. I realized that that was an issue which was gonna be taken over by the people who were on the front lines of the struggle. Meaning mostly African-American people and, you know, to some extent people who were working with them side-by-side in the community. But as a lawyer, it was not the place where I should be focusing my principal attention and that I should be looking to what else needed to be done. I graduated from Yale Law School in 1971, I was married at that point. My husband wanted to move to Southern California to practice law. He had spent a summer out here and loved it at and I was happy to get away from the East Coast in the winter and into a place of opportunity. So, I landed in L.A. without a job and went looking for something in the public interest arena. And I happened to land just at the same time as an organization called the Center for Law and the Public Interest or CLPI was getting started and they had made environmental law their principal activity, although they did actually get involved in some equal opportunity for rights litigation equal employment work, especially, but their main focus was the environment. And so, I went and applied at that point I hadn't taken the California bar so I was just a graduate of law school who needed to take the California bar. So, they hired me as a law clerk and then I succeeded in convincing them that they needed to keep me around because I took on the one topic that everybody agreed was really important, but they didn't know what to do about and that was air pollution.

Greg Dalton: So, in 2008, shortly after you took over chair of the Air Board, I vividly remember being in a glitzy Beverly Hills hotel at a summit that Gov. Schwarzenegger put on. Barack Obama had just been elected, he addressed the group by video I had never seen a standing ovation for a video before and he said that people who care about climate change now have a friend in the White House and there were cheers and his future Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta spoke there. So, take us back to that moment when similar to now there was some lot of expectations and excitement about climate progress in 2008.

Mary Nichols: Well, yes, and similar to now we also we’re coming out of an era when the federal government had been fighting against California and working very actively through EPA and the courts to deny California the right to emissions standards for vehicles for the greenhouse gases that are emitted by vehicles. So, lo and behold, we’re facing the same issue again. It's a repeat of that experience where we now have a new administration coming in, this time with an even broader set of commitments and frankly I think a much longer list bigger bench of people that they are looking out for top positions across the government who get it that climate is a major issue for our time. Another difference I think which is significant is that we know that this election was propelled in significant part by young voters and that climate is one of their top issues. So, politically climate has become relevant in a way that it wasn't before.

Greg Dalton: Right. And coming back to the California timeline. In 2009, the auto industry with another recession. The auto industry was bailed out by federal taxpayers and the federal government took a big stake in General Motors and Chrysler. What kind of leverage did that give California and the federal government to kind of accelerate and increase the CAFE standards for the first time in almost what 20 years?

Mary Nichols: So, there had been a couple of decades in which there had been no action on fuel economy standards. And a great resistance on the part of the Bush administration to setting an emission standard for greenhouse gases. There was the Supreme Court had to tell the administration that they had to at least consider setting an emission standard for greenhouse gases. So, we were starting from a pretty low point, but the fact that the industry had been through the near-death experience and I do want to say that, you know, not all the companies had to be bailed out and even General Motors and Chrysler were paying back the loans that they had gotten from the federal government. So, it wasn't as though they had their arms twisted behind their back and had to sign something, you know, upon paying of debt but it is true that the intense experience that they had been through made them more receptive when they got the call from the White House saying we want to talk to you about emissions. And undoubtedly at that point they were looking ahead towards their future and at least a more receptive mode to the idea that there could be some kind of shared responsibility between government and the private sector for advancing the cause of climate change, and fostering independence from petroleum. So, it was definitely a pivotal moment.

Greg Dalton: Though, you know, think taxpayers made money on the General Motors stock they pay back the loans as you said, but they have short memories as soon as Donald Trump was elected the auto industry was the first industry to issue a statement saying we want some relief we want some regulatory rollback, right. How did that work out for them? They were, as far as I can remember first out of the gun after the election, saying okay we want some relief and they got perhaps more than what they bargained for.

Mary Nichols: Yes. One of the first trips it may have been the first that he made after he took office by president, one of President Trump’s first trips was to meet with auto executives in the Detroit area. And it was with the idea that he was gonna work with them he was gonna help them give them regulatory relief in return for them opening up new plants and creating new jobs in the United States. That was his objective and he believed as a matter of principle that the way to get that would be to hand them a bunch of regulatory rollbacks. They never quite said that that was what would happen and it didn't happen, but he did in fact believe it, and he persisted in granting them more relief than they had actually asked for in that meeting or anytime afterwards because they quickly realized once the news of this meeting got out that they were making more enemies than they were friends among consumer organizations, among many members of Congress and others. It wasn't just that the environmentalists were upset about this. It was a much bigger deal that they were seem to be demanding to completely freeze any kind of standards that related to fuel economy or greenhouse gas emissions and just said they couldn't do it.

---

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation with Mary Nichols, chair of California's Air Board, and a contender to lead the US EPA when President Biden takes office. Coming up, more highlights from a 45-year career fighting for a stable climate.

Mary Nichols: It was thrilling because suddenly you realize a president of the United States a person who is a history maker on many fronts was actually embracing action on climate change.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

---

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. My guest is one of America’s climate champions, Mary Nichols, who’s stepping down after thirteen years as chair of California’s top agency fighting climate change. Let’s pick up our discussion about the Trump administration’s attempt to water down California’s fuel economy rules, that often become national standards because of its big car market.

Mary Nichols: Well first of all there was a period of time during which supposedly the administration was going to try to negotiate with California to see if we could come up with a compromise between zero and the California regulations that did not work out, and there's a long twisted history about that. But essentially the administration was not talking to the industry or labor or consumers or anybody else they just started from the position which was an ideological position that there should not be any use of these emission standards that might impact on fuel economy. So, they weren’t interested in having a real conversation. When that became clear and we reverted to litigation mode. The companies faced a choice they could either side with the administration or stay out or they could throw in their lot with California. And as I think everybody knows General Motors and Toyota, who were the big dogs in the trade association swung their weight behind joining with the Trump administration. They had arguments that they made you know in private as well as in public that basically boil down to the fact that they felt like they were being pressured by the Trump administration into siding with them. And they felt that they were potentially at risk because the president has other tools at his disposal in terms of trade sanction and rulings on various labor and health issues and so forth, in which he could've made their lives much, much more difficult. And so, they wanted to be siding with the federal government and they had lawyers advising them that this might be their big opportunity to escape from the heavy hand of California regulations as well. So, their public argument was that they intervened in the litigation because they wanted a seat at the table, but those that join the litigation took the position that California shouldn't be allowed to set emissions standards for greenhouse gases. Over time, some of the companies that did not support that position. This was a vote within the trade organization and while they're voting may not be quite as complex as the electoral college, it’s, you know, a complicated weighted voting system. Some of the companies that didn't support this idea approached California to see if there was a way that they could work around that. And eventually, what happened was that we did negotiate a framework agreement which was a compromise between no further improvements and the California only regulation which we believed would get to the same overall benefit in terms of reduced greenhouse gases if the companies would apply it on a nationwide basis. And so led by Ford Motor Company but also with the strong leadership and support from Honda and BMW and Volkswagen eventually Audi and you know, Volvo, we arrived at this voluntary agreement which is like an enforceable contract with these companies, whereby they agreed to meet a higher standard across their whole national sales fleet and to not attack California's legal jurisdiction here. And I do think there's a common thread here in terms of my involvement, which is that it's about the merits it’s about getting the results and the environmental benefits, but it's also about protecting California's right to set standards because that has been time and time again the one tool that we the people as a whole have had to really force progress on the part of the industry.

Greg Dalton: And that exception that ability to set higher standards under the Clean Air Act is not enshrined in legislation it could be challenged. California want to enshrine it a national legislation and now you’re concerned that a 6-3 conservative Supreme Court could challenge California's right to set cleaner pollution standards that then become national standards.

Mary Nichols: I don't agree with the basis of your question, I think it's important to recognize that our position is that the original 1970 Clean Air Act which has been reenacted or amended but improved over time does state that California has the right to set more stringent standards for any pollutant regardless of whether the federal government is regulating that pollutant or not. The only condition is that we have to get a waiver from EPA and that we have to demonstrate technical feasibility and a need for the stricter standards. And that’s what we've done hundreds of times over the years and that's what we are doing again with greenhouse gases. That topic is in litigation and of course we don't know ultimately what will happen, but President-elect Biden has indicated that he's not going to support the position that the Trump administration took on that. So, in fact, it may never get to the Supreme Court for adjudication because we’ll go back to what we have enjoyed in the past, which is a relationship of collaboration with the federal government.

Greg Dalton: Right. And that's happened to Republican and Democratic presidential administrations. Trump sued California. California also sued the Trump administration. What happens at all that litigation how many times did you sue the Trump administration and do those cases now go away?

Mary Nichols: Well, I believe that the Atty. Gen. Becerra has filed 58 cases against the Trump administration’s EPA for a whole wide variety of policy changes and regulatory changes, rollbacks, etc. and many of those have been disposed of in and we’ve won them. We have not lost any of them. So, what remains of the existing portfolio. I can't say for each one of those cases, but in general I believe that the overall volume of work for our lawyers will go down.

Greg Dalton: What are some of the personally speaking, what are some of the sweetest victories and bitterest moments of 13 years battling lots of environmentalists battling oil companies battling the federal government. What are some of the highs and lows for you personally?

Mary Nichols: Well, you cited at the outset of this conversation. The event that Arnold hosted at the I think it was the Beverly Hilton Hotel with leaders from around the world and many state governors showed up as well as business leaders and so forth to talk about climate change. And that video from Pres. Obama which I think it was shot, it’s actually before he was even in office. It was shot at his office with a wall of law books in the background as I recall, not terribly high-quality production, but it was definitely Obama speaking and it was thrilling. It was thrilling because suddenly you realize a president of the United States a person who is a history maker on many fronts was actually embracing action on climate change. And it was stunning because it was a realization that what we were talking about wasn't some fringe idea or some kind of European conspiracy that Arnold was a part of. It was mainstream consensus that action needed to be taken to address climate change. And so, that was truly a high point from my perspective. Some of my conversations with members of the outgoing administration in which they were fundamentally disrespectful of California were definitely low points in terms of my career trajectory. But I guess this may sound overconfident, but I believe that if you're right and you have the forces of right on your side and you can appeal to the public ultimately you will win and I think that's what's happening. It doesn't mean that we’ve solved the problem of climate change, but at least we’re beginning to amass the necessary forces to do something meaningful and big about it.

Greg Dalton: Mary Nichols is chair of the California Air Resources Board one of the most powerful climate agencies at the state or federal level of government. Mary has led the board for 13 years under Republican and Democratic governors. During her tenure she’s arguably done more to cut greenhouse gas emissions than any other policy leader in the country. She’s retiring from the agency this year. Richard, a listener, writes, “With control of the Senate in Republican hands can anything be done on climate?”

[00:29:46] Mary Nichols: Well, first of all, as we are having this conversation, the control of the Senate is not yet in Republican hands. Although Mitch McConnell may believe it's going to be there are many forces at work and people who believe that the two seats that are still in contention are going to go to Democrats, which would then change the leadership completely, but the Senate is a pretty slow-moving body in general. The house is a lot more of an activist institution as our Constitution has set it up and they have been passing legislation and resolutions that make it clear that they intend to move on climate and I believe that they will succeed in passing legislation. But I think it's really important to recognize as the Biden administration is already showing that climate action is not just about one particular law. In fact, there are probably are 10 laws that need to be changed or passed in order to get a grip on a problem that is so pervasive as the role of carbon emissions and greenhouse gas emissions in our economy. However, if you look at the Department of Energy, the Department of Defense, the Department of Interior, the Department of Agriculture, Commerce, they all have a role to play through the missions that they are responsible for in shifting gears in the direction of reducing our impact on climate and making our whole society more resilient in the face of the climate change that's already occurring. So it’s a huge undertaking, but it doesn't and certainly putting a stop to the war on any kind of climate change action is gonna be the number one thing. The scrubbing of any mention of climate change from everything from the National Environmental Policy Act to websites from NASA. It's shameful. That is just shameful. And that has got to stop. Once we begin to recognize what the science already shows what the data show us then I think we have to move in the direction of accelerating the recovery of our country from the COVID virus to put money and find money to put into building back our infrastructure and providing stimulus in ways that support the transition to clean fuels, clean energy electrification of the transportation system. It should have deserves to have and I believe ultimately will have bipartisan support, but I don't think you can just look at the makeup right now and say well you'll never get anything passed because I don't think that’s true.

Greg Dalton: Climate was an issue in this presidential selection season, more than any before it made to the debate stage thanks to Sunrise Movement and others and also a growing national consensus. You probably get this as much as I do, individual say what can I do? And there’s quite a debate. Some people will say policies what matters because climate is so big policy, policy, policy, we need policy. And other people will say, hey, individual action is important incremental, I want to do the right thing. Where do you come down on the individual action spectrum in terms of, is it significant or is it a distraction that away from the bigger systemic things?

Mary Nichols: Individual action is not a distraction in fact, it's essential. If people are not interested in the topic even if you have leaders at the very top who were saying, yes, we want to take action. They won't get the support that they need. And I think we've seen certainly in the United States and in other democratic societies that change flows from the bottom up, not from the top down. You have to have people who are willing and able to buy the cleaner vehicles to invest in a new technology and to move to places that are less dependent on having to drive long distances. You’ve got to change the economy and the marketplace and that requires action on the part of the people as they are acting as consumers as citizens at the local level and who they elect but also just the choices they make of what to buy and how to live. Without that, the politicians even if they may articulate the vision are not gonna have the ability to actually move forward and make policy. But it’s interactive again as we've seen most recently with this response or lack of response to the COVID crisis in our country if you don't have national leaders who are willing to set policy and say, wear a mask, then you also don't get cooperation from the people because it's not seen as something that's important it becomes an issue for debate. And therefore, the problem just gets worse. So, it’s really not an either/or discussion. It has to be both.

Greg Dalton: We’re talking about climate change at Climate One. My guest is Mary Nichols, chair of the California Air Resources Board, the state's top climate chief. I’d like to go to our lightning round which is a couple of true or false questions. I know you like this part. So, Mary Nichols. True or false, Jerry Brown is so cheap that he usually lets other people pick up the check at dinner?

Mary Nichols: True once but not anymore. So, I’m gonna say false.

Greg Dalton: True or false. Arnold Schwarzenegger used to fly you up from L.A. to San Francisco on his private jet so you could come and sit in the front row of audience at Climate One events and you could feel the really hard questions I want to post to him?

Mary Nichols: Once. So true once.

Greg Dalton: True or false. Ride-hailing companies increase traffic congestion and the total number of car miles traveled? I don't think that's true. I’m gonna say false.Greg Dalton: Okay. I think one study in San Francisco found that was certainly true. True or false. You really don't like one-word answers?

Mary Nichols: That is very true. Yeah, very true. I mean again your San Francisco study I can't argue with the study, but I'll bet you there is one from someplace else that is not the same.

Greg Dalton: Fair enough. This is association. What’s the first thing – I’m gonna mention a noun and then you say the first thing that comes to your mind unfiltered from deep in your brain. Mary Nichols, what’s the first thing that comes to mind when I say hydrogen cars?

Mary Nichols: Easy to drive.Greg Dalton: What’s the first thing that comes to mind when I say nuclear power?

Mary Nichols: Exists. It's out there. We use it.

Greg Dalton: Last one. What’s the first thing that comes to mind when I say biofuels?

Mary Nichols: Biofuels? Mixed environmental benefits, but can be very positive.

---

Greg Dalton: You're listening to a conversation with Mary Nichols, outgoing chair of California’s top agency confronting fossil fuel pollution, that is destabilizing our climate. This is Climate One. Coming up, focusing on people who live near refineries, and other industrial sources of carbon pollution.

Mary Nichols: Our regulatory programs tend to focus on big regional scale, not on localized impacts. But we've come to realize that there’s no alternative, that the state has to get involved.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

---

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. We’re talking with Mary Nichols, who’s stepping down after thirteen years under Republian and Democratic governors as chair of California’s top climate agency. Despite her outsized role in reducing America's carbon pollution, one of the strongest criticisms of the California Air Board, during Nichols’ tenure, was that it favored wealthy people, and didn’t fully consider communities of color living near industrial facilities.

Mary Nichols: There's definitely been a growing awareness on the part of people at the local, state and federal level that communities have been left behind left out disproportionately impacted by pollution across the board. The very term environmental justice at least first came to my awareness around issues where waste facilities were being sited. There was a whole movement in our country and it was in California too, to take care of solid waste by burning it to make electricity but to keep it away from landfills which communities were definitely trying to get rid of. And over time it's become obvious that there's been less active enforcement less attention paid to the environmental reality, the amount of pollution that people have to live with in low income and communities of color in particular. So, that's a reality the legacy of racism in the way that zoning was done and housing was built has left behind whole areas whole census tracts where people are more vulnerable and suffer worse pollution. That is a real fact. And our programs were by and large are not designed to take account of that. And so, it's been a struggle when people have had to organize and really fight to get the attention that they needed. And certain communities like Flint, Michigan have become household words because of the realization that they were suffering from serious health impacts as a result of neglect of environmental amenities that they just people were not getting fair treatment. The air program is no different. It doesn't have a, you know, the interesting thing, or maybe I think it's an interesting thing is that our regulatory programs tend to focus on big regional scale, not on localized impacts. And the localized impacts which are mostly the toxic concentrations tend to be dealt with at the local level, not by the state or the federal government. But we've come to realize that there’s no alternative that the state has to get involved and we have fortunately we've gotten some very strong legislation in the past few years and from the very start of the market-based programs in the climate arena. The legislature has directed a set-aside of funds that came to the state to address the environmental inequities in some of the most polluted the most impacted communities in our state. So, I think California has been a leader, not just in recognizing but addressing the problems but they certainly are not they’re not solved.

Greg Dalton: Forests are a big part of the climate equation we've seen American West has been on fire this year like never before mega fires each year seems to be escalating. Is that reducing going backwards when a forest burns it releases a lot of carbon into the atmosphere, is that undoing a lot of California's progress? Address the role of fires and forest and carbon and moving to a cleaner.

Mary Nichols: Fire is a necessary tool in restoring the health of our forest. We have to be able to do controlled burning in places where there hasn't been any burning allowed for years in order to reduce the severity the spread and the intensity of the fires. And any time you burn anything there is a release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. So, there's no question that we as the government will be actually participating in putting emissions into the atmosphere. But the flipside of that or the reason for that is that if we don't do it, we will not be able to bring back healthy forests that will grow and store more carbon into the future. So within our cap and trade program we do allow some offsets that come from forest management that is demonstrated to keep trees alive and healthy and absorbing more carbon for a hundred years or more into the future. I think it's one of those things we have to keep looking at continually but I don't believe that it's true that the offsets that have been created in California are taking us backward. In fact, the opposite. We have a model in a program that was developed by the Yurok Tribe in Northern California, which owns a lot of land that had very degraded forest resources and they were able to use the funds that they acquired from offset from the offset market to buy back some of their ancestral land and to invest in improving the overall health of their forest. This is a completely win-win situation and it's one that it's maybe a small scale but it's really worth looking at to see how you can achieve both environmental and social benefits if you have a well-run offset program.

Greg Dalton: My guest today in Climate One is Mary Nichols, chair of the California Air Resources Board, the state's top climate agency. We have a listener, Leslie asks, “Do you think the Biden-Harris administration will increase incentives for purchasing electric cars?”

Mary Nichols: Right now, the federal government incentive which was a tax break has expired. So, it will take Congress to bring it back again. Direct rebates or tax breaks are certainly an important tool in getting over the first cost differential between electric and gasoline models. Although we’re seeing that difference really coming down quickly and some people have predicted that there will be no difference between electric vehicles and gasoline powered vehicles within just the next couple of years, which of course is where we would like to end up. But until that happens, there probably is a need for incentives to help people make the choice for something that is more environmentally beneficial, even though in the long run they will still save money over having to pay for the gasoline and the servicing of a gasoline car because electric cars are much more durable and electricity in most places is still quite a bit cheaper than gasoline. So, that's an important tool, but even more important in decision-making is the question of where you can get the fuel so you can actually use the vehicle whenever you want and wherever you want to. The question of what they call range anxiety has been an issue for years in terms of public acceptance or awareness that there really are electric vehicles that will serve their purposes. And I'm happy to say that nowadays all the newer models of electric vehicles that are coming on the market for the passenger cars and the SUVs and lighter vehicles have the battery ranges in the 200 mile plus which is equivalent to the range that you need for gas stations. And states, and hopefully soon the federal government are getting much more involved in helping to make sure that we have a network of chargers that is available to the public so that people can really enjoy the benefits of electric vehicles. The auto companies are doing a good job of building attractive ZEV, zero-emission vehicles for all kinds of consumers and now they need to match that with the fuel availability in places where people really need to fuel up.

Greg Dalton: Well, as began here we talked about “dieselgate” and VW getting caught cheating on their emissions and California really played a key role in exposing that cheating. One of the penalties consequences was VW building out a charging network across the country. How significant was that scandal in terms of changing not only VW but the industry itself?

Mary Nichols: The penalty that Volkswagen paid for that cheating that they did on their diesel vehicles mostly went to funds that were allocated to overcoming the impact of all the extra nitrogen oxide emissions that people were forced to breathe as a result of the cheating that went on, cars that were sold and driven that should not have been allowed to emit at those rates. So, that money has been directly invested in most cases in turning over old school buses and getting newer buses or cleaning up public fleets. But a portion of it went to an electric vehicle fund because one of the things that the company did as they were marketing the so-called clean diesel vehicles was to try to hold back the market for electric vehicles by saying, oh you don't need to do that that’s way too expensive and unnecessary. You can just buy these very efficient very clean diesel vehicles and it will be at least as good for the environment, which of course wasn't true. So, as part of their penalty they had to put aside some funds for electric vehicle support. And in California that led to the creation of more we had more funding to put into public charging than any amount that the state had ever paid up until that point in any other grant programs that we had ever had. So, it was a big deal. It is a big deal but maybe more significant is the fact that once Volkswagen decided they were going to have to do this they went all in. They not only announce that they were changing their product plans to be all electric in the near future and we know that they are using this as a springboard to change their image and to increase their market share worldwide because the demand for zero-emission vehicles is a worldwide demand. But here in California we have seen and now across the country we have seen Electrify America, which was the company that they spun off has been putting in stations and helping to build awareness and to make it possible for our country to shift over to zero carbon transportation.

Greg Dalton: As we wrap up, we began talking about AB 32 California's landmark climate law which had the required goal of reducing emissions to 1990 levels by 2020. California, I believe met that even a little early. But the outlook for the goals going ahead the next 10 years are less rosy. There’s been some recent projections that California is gonna have a really hard time meeting its goals of the next decade. So, could you address that there are some concern that a lot of the low hanging fruit has been picked and the next 10 years may be harder than the last 10 years in terms of driving deeper decarbonization.

Mary Nichols: You know, having started by career working on air pollution back in the 1970s. I've heard this argument every time the standards got tighter or stricter that all the low hanging fruit is gone everything that was affordable has been done the next slice is gonna be way more expensive and way too difficult. And every time that argument has come up we have continued to move forward in the direction of our clean-air goals set based on health needs. And we have achieved them because technology rises to meet the challenge. It is a fact of life which I think some people have a hard time accepting that if you set strong standards and you create the conditions in which people can make money by developing and marketing the technologies that will help you meet those standards, you can do it. You keep on moving forward towards the direction of cleaner air and we will keep on doing the same thing as we not only clean up the air but reduce our greenhouse gas emissions. It's not that it's easy. It isn't that there's something there just waiting to be done that’s free and gosh, why isn’t just already been done. But if you have a choice in buying a new urban bus or a choice in where your electricity is coming from and it arrives at your home or your workplace when you need it, and is affordable. You don't really care what powerplant actually generated those electrons. And this is the beauty of our system is that we have been able time and time again to find and use and reward those who have come along with cleaner, better technologies for creating electricity creating cleaner fuels. I don't want to, you know, go too much into the ancient history, but when I first started working on air pollution the power plants in the Los Angeles basin burn fuel oil it was 3% sulfur fuel oil. It was by today's standards completely unacceptable. And we fought with the utilities for years and made the switch from fuel oil to natural gas and now, decades later, we’re moving away from natural gas and in the direction of renewables. Each time there's been some resistance it’s not always been a straight line, you know, quick, easy change and it did require policy to make it happen. But once the policy was there and people accepted that it was needed. We got the results that we needed.

---

Greg Dalton: Mary Nichols is outgoing chair of the California Air Resources Board, one of the most powerful climate agencies at the state or federal level. She’s a leading contender to run the US EPA after Joe Biden is inaugurated.

Greg Dalton: To hear more Climate One conversations, subscribe to our podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you get your pods. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or telling a friend. It really does help advance the climate conversation.

Greg Dalton: Kelli Pennington directs our audience engagement. Tyler Reed is our producer. Sara-Katherine Coxon is the strategy and content manager. Steve Fox is director of advancement. Devon Strolovitch edited the program. Our audio team is Mark Kirchner, Arnav Gupta, and Andrew Stelzer. Dr. Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, where our program originates. [pause] I’m Greg Dalton.