What’s a Climate-Conscious Republican to Do?

Guests

Emma Dumain

Heather Reams

Mariannette Miller-Meeks

Danielle Butcher Franz

Summary

The leaders at the top of the Republican party want the U.S. to double down on carbon-intensive oil and gas — and avoid reckoning with the damage fossil fuels cause. Even tax credits meant to incentivise renewables aren’t safe from conservative attacks.

“They are calling these clean energy tax credits ‘green new scam’ level radical climate giveaways,” says Emma Dumain, a reporter for E&E News.

But when it comes to climate, the party is not a monolith. Even Freedom Caucus provocateur Matt Gaetz has said, “The Earth is warming, and I think that humans contribute greatly to that warming, and we've got to be more astute about the research we do.”

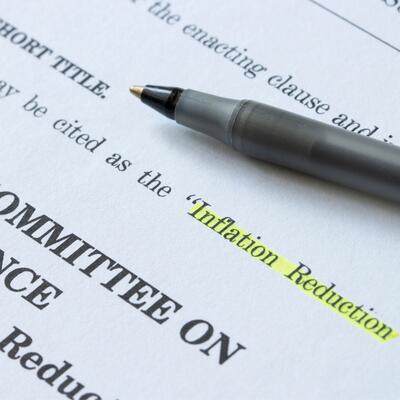

Some conservatives are trying to move the needle on climate action. There are also some Republican members of congress whose districts have benefited from the Inflation Reduction Act. Eighteen House Republicans recently sent a letter to the Speaker of the House asking him not to put the tax credits that benefit their districts on the chopping block.

Some signers of that letter are members of the Conservative Climate Caucus, which was started in 2021 by Representative John Curtis from Utah. Heather Reams, President of Citizens for Responsible Energy Solutions, played a role in the formation of the caucus. Reams acknowledges that it’s worrisome to have climate deniers at the top of the presidential ticket. But she says that members of congress have a voice. “That voice, particularly for Republicans, has changed significantly in the past eight years.”

Now that John Curtis is running for Mitt Romney’s open senate seat, he has passed the position of chair of the Conservative Climate Caucus to Representative Mariannette Miller-Meeks of Iowa. Miller Meeks says, “We'd like to see the caucus grow to [be] similar to the Western caucus or Republican Main Street caucus.” Iowa is actually a leader on clean energy, Miller Meeks says, “Iowa is a state where 50 percent of its energy is from renewables, now 60 percent of our electricity is from wind.” Though she does favor an “all of the above” approach to energy, which relies heavily on domestic fossil gas.

“We have polling that shows 89 percent of young Republicans think climate change is a serious issue that needs to be addressed. And so young Republicans really do care about this issue,” says Danielle Butcher Franz, CEO of the American Conservation Coalition. Polling shows young people on both sides of the political aisle care about climate. But young conservatives have had a more difficult time finding organizations that prioritize climate and also fit within their ideology. The American Conservation Coalition may be able to fill that need.

When it comes to climate messaging, Butcher Franz says of the GOP, “There's been a lot of positive evolution, but it's not enough. And that's not me saying that, that's voters saying that. For every election cycle that conservatives are not talking about climate change in a productive way, they are losing half a percentage point of the electorate. And so what that means is that over the long term, if Republicans are not talking about climate in a way that meets voters where they are, they will become politically irrelevant.”

Resources From This Episode (4)

Full Transcript

Note: Transcripts are generated using a combination of automated software and human transcribers and may contain errors. Please check the actual audio before quoting it.

Ariana Brocious: I’m Ariana Brocious

Greg Dalton: I’m Greg Dalton.

Ariana Brocious: And this is Climate One.

[Music change]

Richard Nixon: Each of us, all across this great land, has a stake in maintaining and improving environmental quality. Clean air and clean water. The wise use of our land. The protection of wildlife and natural beauty. Parks for all to enjoy. These are part of the birthright of every American.

Greg Dalton: That was Republican president Richard Nixon in 1972, asking Congress to pass a number of environmental bills his administration was pushing. Nixon is actually responsible for many of today’s bedrock environmental laws: the National Environmental Policy Act, the Clean Air Act and the Endangered Species Act.

Ariana Brocious: And he also created the Environmental Protection Agency and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Greg Dalton: Nixon was quite green by today’s standards. But that was a long time ago. Fifty years later, the Republican party has a slightly different message.

Donald Trump: All of this with the global warming and that a lot of it's a hoax. It's a hoax. I mean, it's a money making industry, okay? It's a hoax.

Greg Dalton: That was, of course, former president and current Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump on the campaign trail in 2016. And he made good on that position when he took office. He pulled the U.S. out of the Paris Climate Accords….and rolled back a lot of pollution protections. We lost a lot of ground during his four years in office.

Ariana Brocious: And now we’re hearing about this thing called Project 2025, put out by the very conservative think tank - the Heritage Foundation. Project 2025 is basically a playbook for an incoming conservative administration, with chapters on everything from trade to the department of justice, and even the EPA. To get a sense of its take on climate change, I want to play a clip from a Project 2025 training video, leaked by ProPublica. This is Bethany Kozma, who was a senior official in the Trump administration.

Bethany Kozma: Climate change allegedly is everywhere. And if the American people elect a conservative president, his administration will have to eradicate climate change references from absolutely everywhere.

Ariana Brocious: “Eradicate climate change references.” That’s pretty extreme.

Greg Dalton: It is. And they want to do away with EPA.

Ariana Brocious: While Trump has tried to distance himself from Project 2025, that message is in keeping with what his administration did when he was in office. Remember how they just took down webpages that dealt with climate change?

Greg Dalton: Yeah, sort of mind-boggling. But while Trump may be the loudest voice in the Republican party right now, Republicans aren’t a monolith. Florida Representative Matt Gaetz believes in climate change which has hit his district hard.

Matt Gaetz: The Earth is warming, and I think that humans contribute greatly to that warming, and we've got to, I think, be more astute about the research we do.

Greg Dalton: Florida is facing so many climate impacts already: sunny day flooding, severe hurricanes, sea level rise. It’s undeniable, even to his conservative constituents.

Ariana Brocious: And then there are politicians who seem to be inching toward acceptance… For example, back in 2014 Florida Senator Marco Rubio said: I do not believe that human activity is causing these dramatic changes to our climate

Marco Rubio: I do not believe that human activity is causing these dramatic changes to our climate

Ariana Brocious: But in 2018 he had a different take.

Marco Rubio: Scientists are saying that humanity and its behavior is contributing towards that.

Ariana Brocious: So the Republican party is in this interesting moment: it seems like the faction of the party that does not see climate as an issue is getting more strident in that view. Meanwhile others are confronted with the realities of the climate crisis, which is pushing their colleagues to start acknowledging the problem too.

Greg Dalton: Right, it's a dynamic situation. And all of this is made more complicated by the influx of investments from the Inflation Reduction Act that are disproportionately going into red parts of the country. Bloomberg reported that areas represented by Republican members of Congress have received four times as much money as districts represented by Democrats.

Ariana Brocious: One example is a steel plant in Middletown, Ohio. J.D. Vance actually wrote about it in his memoir Hillbilly Elegy – he described the plant as an “economic savior” for his grandparents. The plant has received $500 million from the Biden Administration to move away from coal, which will clean up the air and help the plant stay open for another generation, according to a report from E&E News.

Greg Dalton: But a second Trump presidency could threaten future funding like that. Some Republicans are actually worried that if Trump wins the White House their fellow Republicans are going to roll back the green energy money flowing to their constituents. In fact, 18 House Republicans recently sent a letter to the Speaker of the House asking him to protect tax credits and incentives in the Inflation Reduction Act.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, this was a pretty big, public move – with a pretty big, public backlash. Because then Texas Republican Congressman Chip Roy blasted them for aiding the “climate corporate cronies destroying our country.”

Greg Dalton: There’s really a struggle going on in the party. I talked about all of this with E&E News reporter Emma Dumain. She’s been covering capitol hill since 2010 and she sees fractures in the Republican caucus over the IRA.

Emma Dumain: People like Chip Roy and other members of the Republican party and hardline conservatives don't think that anything in the Inflation Reduction Act ought to stick around. They think that it's a huge big government handout. They are calling these, clean energy tax credits, you know, green new scam level radical climate giveaways. They're calling them subsidies. Rather than tax incentives or credits that people can use, to bolster what would normally be private investments to build new clean energy projects and, infrastructure initiatives around the country, that would, Put people to work, create jobs, create economic opportunities while shifting, us away from traditional energy sources, fossil fuels to, building batteries for electric vehicles, for, being able to convert housing to solar and electric,

Greg Dalton: And when I saw that, I was surprised because, you know, Austin, Texas, now the home of Tesla and other tech companies, a little bit of a blue dot in Texas, you know, Chip Roy’s district includes some areas near San Antonio, rural areas. It's not all of Austin. Do these members diverge from the interest of their districts? And is that okay? Because they're voters. You vote on other matters. They're not voting number one on this clean energy tax credit.

Emma Dumain: Yeah. You know, the conflict that's emerging right now among House Republicans. You have, you know, through the 18 Republicans who signed that letter, they feel strongly that their constituents are paying attention, that they are seeing these investments in their districts as a result of the Inflation Reduction Act, jobs being created, economic projects coming into their communities that would be missed, that would have, really a devastating impact on their local economies, were they to go away? Were these tax credits to evaporate, break that came out of the IRA? For other Republicans, they're reaping the benefits in their districts, but there's some magical thinking where they are pretending that they were not the results of the Inflation Reduction Act. So, you know, there's a lot of communication breakdown and a lot of Republican lawmakers, frankly, getting away with not being honest with constituents about where these investments are coming from, and I can absolutely see a scenario where the people Chip Roy represents just don't know.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, right. And there's also that, yeah, the “vote no and take the dough” as some say. Representative Andrew Garbarino of New York spearheaded that letter to Speaker Johnson. He represents the second district out in the middle of Long Island. Tell me about him, who he is and what his district is like.

Emma Dumain: Yeah. So Andrew Garbarino is, you know, one of these, you know, there's a handful of moderate House Republicans from New York. He's one of the outliers in his delegation right now and that he is actually not facing a tough reelection. He's not in a swing district, so he has the luxury to be taking the position where he is right now, which is, supportive of the Inflation Reduction Act. And what investments they've brought to his part of the country. And he also has the luxury of being able to speak out, on behalf of investments being seen in other parts of the country. He is the co chair of this house bipartisan climate solutions caucus, which is a group of evenly divided between Democrats and Republicans trying to find common ground on climate policy. So, you know, the support for these tax credits is, you know, an opportunity, maybe perhaps a rare opportunity to side with Democrats, on energy and environment, climate policy.

Greg Dalton: And you said he's an outlier. So most of the Republicans saying, Hey, these tax credits are a good thing are in swing or vulnerable districts. So what does that say? They're worried that they might lose their job because of these tax credits. Their voters like them?

Emma Dumain: It's a tough situation, right? Because on the one hand, when you're running in a primary, you're going to have people running to your right. And you have to be really careful not to say too many good things about the IRA. But then you're running in a general election where you have to move towards the middle so you don't alienate independent minded voters who could vote for Democrats. So that's what you're seeing right now. You didn't see a lot of these members other New York Republicans who signed the letter. You wouldn't have seen them and you didn't see them come out in support of these tax credits as they did during their primary season. You're seeing it during the general where they need to appear independent and they need to reach those moderate Democratic voters who could be inclined to vote for the Republican incumbent if there's enough ideological alignment on issues that are important to them.

One member of the House who's running to hop to the Senate is John Curtis from Utah, Republican of Utah, who founded the conservative Climate Caucus in the House. He's running for Mitt Romney's seat, who was, you know, favored climate action and when he was governor of Massachusetts and in the Senate, you know, how does climate factor into John Curtis's primary in Utah? Was it an issue? Was it not? Did it hurt him? Did it help him?

Emma Dumain: You know, I was just talking to someone about this yesterday where

it probably had little effect, which is a victory for someone like John Curtis. You know, if it helps you, great. If it hurts you, that's a problem. If it doesn't help you or hurt you, if there's like, you know, if it's a neutral factor, that's a win, right? Because traditionally, you haven't had Republicans leaning in on climate action. And if you have, it's been a real problem in a primary, in a conservative state or a conservative district where your opponents want to use it against you to show that you're, you know, this lefty, softy, You know, RINO, Republican in name only. There were efforts to tie him to climate action, his opponents would say things from time to time and try to shop some, you know, negative story to the press about his climate ambitions.

Greg Dalton: So John Curtis, Republican of Utah, we've been talking about did found or co found the conservative climate caucus now over 80 members. Tell us about that caucus. Who's in it? What parts of the country does it represent? Is it really a force for moderating the Republican stance on energy and climate issues?

Emma Dumain: Yeah, so the conservative climate caucus, as you said, has more than 80 members. It was founded in 2021. So it's not too old. It's had an interesting role in that it has been mostly an educational outlet. They have meetings with experts and you know, they wouldn't have had it with administration officials because, I don't think that they would have invited Biden administration officials, but probably former Trump administration officials. They've done some tours. They've done some summits. They have held back on making policy recommendations and agitating for certain policies to come to the floor. They don't whip votes. They don't take official positions. Every year they've since they've been around, they have sent representatives to the UN climate summits known as the COPs. They're about showing that Republicans do want to engage on this issue and do care about this issue. One of the mission statements of members of the conservative climate caucus is that you agree that human contributions are exacerbating the climate crisis. So, you know, you can't be a climate denier and join. At the same time, we haven't seen them take big swings and assert themselves in a way that is affecting the overall policy agenda. There was a whole week where they did a bunch of legislation on the House floor and they called it Energy Week, and it was all about, you know, a resolution disproving of a carbon tax, reversing efforts to ban gas stoves. It was, barring Biden from tapping into the strategic petroleum reserve, expanding drilling. So this was where the conservative climate caucus could have jumped in to say we believe it does X, Y and Z and they stayed on the sidelines and were silent.

Greg Dalton: So these sound like symbolic votes that are aimed to get, you know, social media posts are with no intention of so if If the republicans get the white house the house, senate, etc. If there is some Republican control, what do you see in terms of moving from the symbolic votes to votes that actually are aimed at, you know, crafting policy?

Emma Dumain: I think if there's a governing trifecta for Republicans next year, Republicans who are in the conservative climate caucus and even the bipartisan climate solutions caucus are going to have to decide where they want to make their voices heard. It's going to be, it's going to be really interesting to see how the conservative climate caucus and the bipartisan climate solutions caucus evolve in a scenario like that.

Greg Dalton: Well, thank you for giving us a setup of what the landscape looks like going into this election on the right on the energy and climate scene. Emma Dumain. Thanks so much for sharing your insights on climate one.

Emma Dumain: Thanks for having me.

Greg Dalton: That was E&E News reporter Emma Dumain. Coming up, some conservative states are leading the way on generating renewable energy.

Marianette Miller Meeks: Iowa is a state where 50 percent of its energy is from renewables, now 60 percent of our electricity is from wind.

Greg Dalton: So what’s happening with the climate-conscious wing of the Republican party? That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Ariana Brocious: Please help us get people talking more about climate by sharing this episode with a friend. And we’d love to know what you think of the show. Please give us a rating or review. You can do it right now on your device – and it really helps people find the show. Thanks!

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton

Ariana Brocious: And I’m Ariana Brocious. As we heard earlier from reporter Emma Dumain, there are a few different factions within the Republican party when it comes to climate change. And right now the faction that wants to take action on climate is in the minority.

Greg Dalton: But It's also not as small of a minority as it was even 5 years ago. That’s partly because groups outside the party are helping to make the case for why conservatives should take an interest in climate solutions.

Ariana Brocious: One of those groups is Citizens for Responsible Energy Solutions, a nonprofit that works to engage Republican policymakers about climate and energy issues. It’s led by Heather Reams. And she has an interesting story about how she influenced the creation of the Conservative Climate Caucus in the US House of Representatives. About eight years ago, Reams was on Capitol Hill speaking at an event for congressional staffers. And she told them: there are three big reasons Republicans should care about climate.

Heather Reams: One, protecting the environment should be a bipartisan issue. Two, that the different kinds of energy sources that we produce in the United States, How can we think about our technologies and export them as a platform for Republicans. And then, three, when Republicans do good things to the environment, it's been crickets. And, where's the incentive for Republicans do something good that's beyond knowing the right, it's the right thing to do.

Ariana Brocious: Those points caught the attention of Utah Congressman, and future co-founder of the Conservative Climate Caucus, John Curtis.

Heather Reams: And he walked up to me and I saw this pin, this, the member pins, they wear pins. And I can just see it coming right at me with a staffer next to him. I'm like, oh boy, what did I say? And he's like, wow, I've been looking for this. This is incredible. Would you please come to my office? Can we set up a time and we can talk? And we talked a little bit there. I asked him for what state he was from. He said, Utah. I'm like, Oh, well, I feel like the West kind of gets this from a conservation standpoint. And he's like, I do. But this idea of talking to Republicans is baffling to me. I've got a young district, one of the youngest districts in the country. I've got a conservative district. And I need to figure out how to get this right so I can teach other people how to talk about climate and the environment and energy in a really cohesive way. Like, well, I'd love to talk. That's why I'm here.

Ariana Brocious: Great.. So now the conservative climate caucus boasts more than 80 members. There's a separate group, the bipartisan climate solutions caucus in the Senate. It has a growing number of Republican members, yet both members of the Republican presidential ticket are climate deniers. So cool. It seems like there's these forces pulling in different directions within the party. How would you describe the current state of climate and concern about climate within the Republican Party?

Heather Reams: Yeah, I understand there's a concern of having so called climate deniers in the Republican party, the top of the ticket. But I, I think there's just so much more than the president and the vice president and policymaking that the equal branches of government and members of Congress also have their voice. And that voice, particularly for Republicans has changed significantly in the past eight years. I also have noticed in the last two administrations that what the White House says sometimes tends to be a little bit more on the political side and rhetoric and then what's happening at the Department of Energy and what they're doing tends to be different than what's coming out of the White House. It tends to be a little bit more all the above. It tends to be a little bit more moderate. And this is regardless of the parties. I'm not saying they're the same. They definitely are not the same. But I do, I know that, but I've seen that. But I feel like you see, like for instance, Secretary Rick Perry, heading up the Department of Energy, was a huge fan of our national labs. And these national labs are doing a lot of work on clean and renewable energy and he was very complimentary of them. Secretary Perry spoke at National Clean Energy Week as a Republican, talking about the benefits of clean energy and how it impacted our economy, our national security, energy affordability, and the environment. Those weren't talking points written out of the White House, I assume. So, so,

Ariana Brocious: but so I hear you. I hear you in saying that there's power among Congress and certainly when it comes to making policy, that's where those seats of power exist. And that department staff can exercise some amount of autonomy, perhaps, or there can be layers in a given approach. But still the president holds veto power. The president's the one that signs the bills and also leads the party and is representative nationally of whatever our attitude is toward these different issues. And so, is there concern among peers of Republican members of Congress that you do talk with about the fact that if Donald Trump is reelected, that there's going to be, I don't know, a loss in climate progress.

Heather Reams: There's definitely concern. I won't, I'll certainly, agree with that. And with I think some understanding of the Republicans have known they've they're digging in, they're doing more, and some of these Republicans who are leading these caucuses, for instance, maybe thinking about, how do they, how do you navigate a president Trump? Are in a precarious position leading a caucus? I've not heard from anyone who's leading a caucus on the Republican side that they will step down. Because of the president, if it's a president Trump, I've not heard that. But certainly there's a conversations that we should have about, there is a role for Congress to play in it. It's maybe not a counterbalance to the white house, but thinking about, let's say the Paris accords and the president Trump withdrawing from Paris as he's done before, and he's also said that he would do that again. But these same members have a history of going over to COP each year and having bilateral conversations. And I would expect that to continue. So, getting members engaged early on, I think, should continue on. And I think it just shows how important the work is to continue to develop members of Congress. Ultimately what we want to see is a president who acknowledges that the climate is changing, recognize that the humans are having an impact on that and that the U S has a role particularly in policy to be able to address global climate change. But members of the caucus, the conservative climate caucus do agree with that. So, ideally one day we're going to have a president of the Republican party who would acknowledge that, but I think it's a very different dynamics than we had in 2016, whether it just wasn't the infrastructure or conversations in the Republican party about climate.

Ariana Brocious: So under the Biden administration, we've seen the largest investment in climate and renewable energy ever under the, largely through the Inflation Reduction Act, also the bipartisan infrastructure law. Georgia has become a manufacturing hub for batteries and other components of the clean energy transition, though its Republican Governor Brian Kemp says that investments from the Inflation Reduction Act have actually hurt the state. How is this huge federal investment in renewable energy, new technologies being received in other conservative states?

Heather Reams: Yeah, I think it's, it is mixed. As the vote for the IRA was a partisan vote. So not a single Republican voted for it in the house or the Senate. And it was procedural. There's a lot of things in the bill that Republicans had supported, but procedurally using the process of reconciliation, Republicans were not in favor of it. So, it was a very much a political vote and an unfortunate vote. That being said a lot of districts, a lot of red districts are benefiting from the IRA. And it's creating some challenging dynamics for these members of Congress. However, Governor Kemp didn't have to take that vote nor did other Republican governors and nor did their state legislators. So I feel like that the political challenge really is at the federal and congressional level, more so than it is at the state and local levels. And you start seeing these businesses coming in, and the transformations in rural areas and bringing in dollars they hadn't had before and investments in roads and schools and infrastructure, broadband. This is significant in thinking about the next layer of health care, hospitals and things that can improve livelihoods and outcomes in life. It gets pretty exciting thinking about that.

Ariana Brocious: What do you think of the Biden administration's climate policy and, Presumably a continuation of that we would see under a potential Harris administration.

Heather Reams: Well, there's a lot of pieces that we, like a lot of that's coming outta the Biden administration through the IRA for instance, that were, that had a lot of, bipartisan support. I think what's just challenging is, when you have a Democratic administration putting out policy, it can also have some Republican undertones to it, or Republicans would like it, but where it came from, the politics can be really tough to sell on Capitol Hill. So being part of that narrative and that dialogue is important for us to look at the legislation and say, this is equivalent to what we endorsed last year. You endorsed last year, remember so and so. So, recognizing the politics is challenging if we can navigate the politics of the policies sound. So, it's, we're still in a, and of course, as in 2024, and we're now in the silly season of politics. So it's really tough to get anything passed, but on the other side of the election I do expect some more movement in the lame duck. And then of course, with a new Congress, a new president, a lot of new coming up our way in 2025, which just opens up a lot of opportunity ideally for some good problem solving to advance climate policy.

Ariana Brocious: That was Heather Reams, President of Citizens for Responsible Energy Solutions. As we heard, Reams and CRES played a role in the creation of the Conservative Climate Caucus, which was founded in 2021 by Utah Representative John Curtis, who also served as its chair. He summed up the vision for the caucus pretty succinctly:

John Curtis: We care deeply about this earth, care deeply about our stewardship, but we have some ideas that may differ about how we reduce emissions and what path will reduce emissions, quickest and most efficiently.

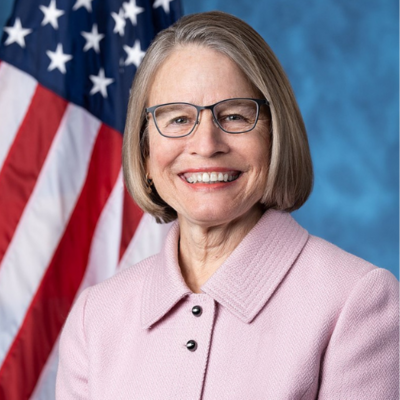

Ariana Brocious: Now, Curtis is running for Mitt Romney’s open seat in the senate, and the Conservative Climate Caucus has a new chair: Iowa Representative Mariannette Miller Meeks. And while she has strongly criticized the Biden administration’s energy policies, she's also been a strong advocate for both home-grown wind and biofuels.

We talked recently about the state of climate policy within the republican party and her vision for the caucus.

Mariannette Miller-Meeks: Well, certainly we want to grow the caucus and it started out as an avenue really for information for sharing of information, sharing on what things were happening in different states and different districts. And so we'd like to see the caucus grow to similar to the Western caucus or Republican Main Street caucus, other caucuses where, there's, we may do trips to individual’s districts. We actually, the conservative climate caucus did a trip to Portland, Oregon, to Laurie Chavez dreamers district. Uh, we visited Hop Works, which is a brewery brewery, and this is Sustainable practices, they were doing what they were doing with grain after the alcohol had been pulled off and distilled, um, you know, how, what energy sources they were using. We also visited a facility that was using natural gas and methane to make hydrogen and where, you know, the, uh, where that end product hydrogen was going and how it was being utilized for energy. Um, so, you know, taking visits to other members district visiting. Uh, you know, uh, new energy, new research. And one of the things I'd like to do is have people visit. Um, I, I visited MISO which is our grid operator for the Midwest, whether it's MISO or another one to be able to visit with them and learn from them also from the utility companies. So, I think there's a lot of education. We can do trips that we can, um, you know, visit with different energy producers. Uh, whether that's a carbon based fuel or that's a newer based fuel, um, hydrogen facilities, I think is one of the things that we're all very interested in doing, uh, and then what's happening on fusion. So looking at an abundance of energy sources, uh, as long as they reduce emissions.

Ariana Brocious: So when you're taking tours like this, and maybe, maybe these tours are a part of it, how do you make the case to fellow Republicans who are not members of the caucus yet that they should care about climate?

Mariannette Miller-Meeks: Well, first and foremost, let me just say that Republicans do care about climate. So they care about climate and they care about the environment. It's a myth that they don't. They may not agree with everything being put across by radical environmentalists on the left, but they certainly care deeply about the climate and deeply about the environment. Also, Republicans, many of them are hunters and fishers. And so. You know, I have, I have hunters and fishers come up and talk to me all the time about habitat, whether that's habitat for ducks, habitat for pheasants and quail, habitat for deer, uh, talking about waterways, talking about clean water. So we're actually all working in this space. We just don't necessarily, you know, Uh, follow along with the international panel on climate change with the U.N. where we may have some disagreements with is where, uh, you know, where, uh, the left makes, uh, what they would consider investments, what we would consider malinvestments in favoring certain energy types. So in Iowa, Iowa is a state where 50 percent of its energy is from renewables, now 60 percent of our electricity is from wind. We are a net exporter of energy. People don't think of Iowa as an energy state, but we are an energy state. Many other states want the renewable energy that we produce. So we have wind, we have solar, but we also have ethanol. We have biodiesel, we have biomass, we have manure digesters that create energy, both thermal and electric. Um, we have compressed renewable natural gas, we had nuclear and are trying to know, come up with, um, a program to bring our nuclear back online. We're proponents of nuclear, small, modular nuclear reactors. So it's amazing the variety of energy sources. And because of that, uh, sustainable, renewable energy, we also have farmers that are very much into sustainable, uh, regenerative ag. So we have a variety of ag practices. I go to their symposiums, uh, with them. I have a farmer that has gone to COP the past several years in

Ariana Brocious: conference of parties. Mm hmm.

Mariannette Miller-Meeks: yeah, he now has a closed loop farming operation, which is really incredible what he has done both in utilizing energy on his farm, but also selling energy and electricity back to the grid.

Ariana Brocious: I was gonna ask you about Iowa because it is such a leader in renewable energy. And I'm curious, you know, all those different types of fuel and energy sources you listed, it is impressive. That's what's often kind of framed as an all of the above approach, which I believe you favor in terms of energy. However, the head of the Republican presidential ticket, Donald Trump doesn't seem to favor all of the above. He's very interested in expanding, uh, oil and gas production, um, on public lands and so forth if he were reelected. That's kind of been his stated position so far. So what type of energy policy would you advocate for if he were reelected in the fall?

Mariannette Miller-Meeks: I'd continue to advocate for what I've been advocating for, and that is for, uh, you know, all of the above energy types. Energy demand is going up. Uh, we know that American natural gas is 40 percent cleaner. Uh, we know that emissions in the United States, uh, have decreased, uh, over 20%, more than any other country. And a lot of that is due to natural gas, uh, which is cleaner. We know that if you really are concerned globally, uh, then the U S should be exporting more of its natural gas because it's a cleaner natural gas. So I'm not opposed, uh, to having, um, we haven't seen leases on public land through the Biden administration. I'm not opposed to that happening because I would rather have natural gas being utilized in another country from America than to have it from Russia, Venezuela, or have coal fired plants being produced, uh, by China to provide energy. So energy demand is going up, and how are we going to meet those increased energy demands? And that's at today's level. Even the first conference of parties I went to in Glasgow, Scotland, everybody admitted energy demand is going up. It is not going down now. Add to that that you're trying to electrify an entire economy that too increases electricity demand and then add to that AI and data centers. And AI and data centers alone take almost as much energy to, um, that would power or electrify, you know, a moderate size city such as Des Moines here, which is our largest city in Iowa. So to me, it's how do we how do we meet increasing energy demand? How do we prevent blackouts? And how do we do that in the context of being able to lower admissions? I think that carbon based fuels and liquid fuels will be around for a long time. But I also think that there are shifts where it's practical, where it makes sense, where you will have electric vehicles or other types of energy production. Um, and then the next thing is, um, how do we know that just because there are zero emissions, uh, at electricity generation, what about from its inception and to its disposal? And so in Iowa now, one of the things we're looking at is how do we dispose of wind blades? Uh, what do you do with solar panels that have reached their life expectancy? What are we doing about the mining practices that are in the Congo and China and Russia continuing to acquire, uh, minds in, uh, in Africa with bad environmental practices and with child labor. Um, what about the processing, uh, the amount of earth that you have to move to get rare earths, to get cobalt, uh, to get lithium that are for battery storage? Um, you know, all of those things have an environmental impact as well. So I think you have to look at it in its totality. And I think we always have. We also have to recognize that it's dynamic. I think it's often young people because they've not had this lifespan to see things change. They think things have to happen right now, this second, uh, because they see it as static information is dynamic. We are going to come up with new energy sources. Uh, it's, you know, I've thought often about maybe we need to have a congressional app challenge on the next energy, not just the congressional art challenge. Or the congressional app. But, you know, what's the next energy source? Uh, so we know that there's a lot of change that's going to happen as we build upon that knowledge. Um, and then some of this is how do we respond to, uh, to weather and climate? So how do we make ourselves more resilient?

Ariana Brocious: I want to get to that question, but I want to respond to a couple things you've said, because I think you've pointed out very accurately that there you do have to take a close look at the full impact of any energy source. And we know that this is part of why natural gas facilities in the U.S., that why there's opposition to them is because of the disproportionate impacts often borne by communities of color or disinvested communities, where those facilities are sited, either where they're extracting or where they're burning. And that's part of the objection to continuing that industry. So from the outside looking in, um. It can seem that there's a divide in the Republican Party between those like yourself, John Curtis, very concerned about climate, active, engaging on it, um, and those who maybe are a minority, uh, but who will still say that it's a hoax and that renewable energy is, is a waste of time. Do you think that's true? And do you think that the party is going to unify more in one direction, or is this divide going to continue?

Mariannette Miller-Meeks: Uh, I think there, there, there are divides in both parties. Uh, and I think what's most important is that, uh, you know, we continue to advocate for, the, uh, Issues that we think are important to us that are important to our districts, um, that we continue to ask for a national energy strategy so that we know what the plan is and how we're going to meet, uh, you know, how are we going to meet increasing energy needs? I can tell you that Republicans are unified in EPA policies that take 30 percent of power plants offline within a decade. And how are we going to make up for that energy? And, um, and states of both, uh, blue states and red states have experienced blackouts and brownouts and power shortages. And so there's a lot of concern on how we're going to meet those energy needs. And we're not hearing that from the administration or from the left. So there are things that we are all very unified on. There are things that we work on in a bipartisan fashion, uh, but in each party, no one is going to have a hundred percent. It's like being married or, you know, uh, being siblings. You're not going to, you love each other, but you're not going to agree on everything 100 percent of the time.

Ariana Brocious: Representative Marianette Miller Meeks is from Iowa and she is chair of the Conservative Climate Caucus. Thank you so much for joining us on Climate One.

Mariannette Miller-Meeks: Thank you so much. It was great to be with you. I really appreciate it. Ariana.

Greg Dalton: Coming up, the push for more climate engagement in the Republican party may come from its younger members.

Danielle Butcher Franz: We have polling that shows 89 percent of young Republicans think climate change is a serious issue that needs to be addressed. And so young Republicans really do care about this issue.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton.

Ariana Brocious: And I’m Ariana Brocious. Both young liberals and young conservatives consider climate an important issue that they want their political party to address. For liberals, there are a number of groups that represent that need, the most prominent being the Sunrise Movement. But for young conservatives, finding an organization that represents their views has been tough.

Greg Dalton: That may be changing. The American Conservation Coalition describes itself as, “dedicated to mobilizing young people around environmental action through common-sense, pro-innovation, and limited-government principles.”

Danielle Butcher Franz is the group’s CEO and she has a unique background for someone who runs a conservative organization.

Danielle Butcher Franz: I grew up in rural Minnesota, in a very politically active family. My family was involved with the local DFL party,

Greg Dalton: DFL stands for the Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party, a political powerhouse in Minnesota that affiliates itself with the national Democratic Party. Gov. Tim Walz is a member of the DFL.

Danielle Butcher Franz: and so some of my earliest memories are honestly going to, parades and handing out stickers for DFL candidates. Or listening to NPR on the way to school in the car or talking about current events at the dinner table.

Greg Dalton: Danielle Butcher Franz shared more of her story with Climate One’s Austin Colón.

Danielle Butcher Franz: As I grew older and started participating a little bit more in conversations instead of just listening, I almost started playing devil's advocate a little bit. You know, I was at that angsty teenage phase where I want to poke holes and argue a little bit. Um, and, and so I did that around the dinner table and the more I did it, the more I realized, wait a minute, I might actually believe the arguments that I'm making. I might actually think that this makes a lot of sense to me and I'm not connecting the dots in the same way that my parents are. I was actually too afraid to tell them at the time that I thought I might be a Republican. And so I started an anonymous Twitter account called Republican Sass. Um, as, as teenage girls do when they

Austin Colón: Right.

Danielle Butcher Franz: with their parents, they take it online. Um, and so I started tweeting these opinions and, um, looking for a community of people who might agree with me because most of the people in my life up until that point were left of center and were, you know, progressive Democrats. And I found a community of young people who thought like me and who valued the things that I valued. And that really sort of gave me the courage to say, yeah, this is, this is what I believe. This is how I see the world. And, um, of course, when I had finally the courage to tell my parents that I thought I was Republican, they just laughed and said, yeah, we, we had a feeling. Um, and it's never really gone any more seriously than that. We still have a great relationship and, and we know that despite seeing things differently, we can. still have the same, um, values and the same things that we care about.

Austin Colón: that's so funny because. I feel like I have a very similar background, except, you know, politically opposites. My family, is very conservative. And as I got older, it was the same thing. When I was a teenager, I started feeling like, you know, I'm going to start arguing against some of those very arguments and pretty much ended up in the same place. My family and I are also still very very close I think it's good for people to hear that you can have you know disagreements without Cutting people out of your life. I'm curious the one issue that Kind of really got me questioning what I believed was the environment and climate. And so, I'm curious when climate and the environment became an important issue for you.

Danielle Butcher Franz: So climate and the environment were always important issues for me, and I credit a lot of my upbringing to that, for a couple of reasons. Number one, like I said, I grew up in rural Minnesota, and if you've ever been, you know that it's full of beautiful lakes and lush woods, and I spent a lot of my time as a child on those lakes and in the woods playing with my siblings, and so I always, really cared a lot about the environment around me. Um, the next reason is we spent a lot of time road tripping to see extended family in the summers. And we would use that opportunity to go through national parks. And I got to see just some incredible landscapes as a child that I wouldn't have seen if we weren't making those road trips. And then thirdly, or finally, when I was also about in middle school, my dad got a job in the solar industry, and I was able to see firsthand how clean energy can lift up rural communities and how it can really serve as a lifeline to people who are impoverished and who, are struggling with energy security. So where I grew up, we have this challenge that's commonly referred to as heat or eat, which basically means in the wintertime, when a family is struggling with economic insecurity, sometimes parents have to make the choice of, are we going to heat the house or are we going to pay for food? And my dad's job in the solar industry, he was installing solar on low income homes, which was providing more economic freedom to those homes because they no longer had to make those choices.

Austin Colón: Let's skip ahead a little bit and I'm kind of interested in what led to the creation of the American Conservation Coalition.

Danielle Butcher Franz: Yeah, of course. So as I mentioned, um, around those teenage years, I started this Twitter account and I found a community of like minded young conservatives. Um, and the Twitter account gained a following pretty quickly. I think within a year it had about 20,000 followers. Um, and so eventually I stopped being anonymous and I put my name on it.And as soon as I put my name on it, I started getting all of these opportunities to attend events and do internships and, you know, write op eds and things like that. So I had formed a pretty good network of young conservatives who were politically active and we would see each other at events like CPAC and we would get to talking about things. Um, and one of those young conservatives was Benji Backer, ACC's founder. And, we basically all sort of came to the consensus that The environment is an issue all of us cared about, but we really didn't see representation from Republicans on what the conservative approach to environmentalism looked like. This was 2017, so this was about the time that Trump had called climate change a Chinese hoax, and me and my fellow conservatives didn't believe that it was a Chinese hoax. Uh, we think it's a serious issue that required serious solutions, even if we didn't necessarily like the solutions on the left, like the Green New Deal. And so we thought that this is a huge gap in the conservative movement. So we founded ACC to bring conservative voices to the table on environmental issues and show conservatives how their values can be applied and adhered to in a way that is still environmentally successful, but also allows our communities and our hometowns to thrive.

Austin Colón: So let's, let's talk a little bit about that divide. Because you have people like John Curtis and even elsewhere in this episode, we speak to, uh, Marionette Miller Meeks, um, who are trying to, you know, implement conservative solutions for climate, trying to get members to care about climate. And then, as you mentioned, you know, people like Donald Trump call it a Chinese hoax. So specifically for young members of the party, um, what effect does that have on them?

Danielle Butcher Franz: Yeah, that's a great point. And actually, we have polling that shows 89 percent of young Republicans think climate change is a serious issue that needs to be addressed. And so young Republicans really do care about this issue, despite maybe having different solutions than their counterparts on the left. I would say that the Republican evolution on climate over the last, you know, 10ish years has been very encouraging for young Republicans. I think you're seeing more and more conservative leaders willing to stand their ground and offer their own solutions and even work in a bipartisan way on these issues. The Republican Party really has come a long way, especially in Congress. The top of the ticket, you know, Donald Trump and, that sort of wing of the party, I think, still have a lot of room for growth. But I think young Republicans are encouraged to see that they are being listened to. And one point that I think is really important to make, because I get this a lot when I'm speaking with media, is young Republicans don't necessarily see climate change in the same way that the left does. I think for a lot of young progressives and a lot of young Democrats, climate change is the defining issue that they will vote on. And you see that in the Sunrise Movement and a lot of the other more grassroots oriented groups on the left. Um, and I think that for the climate movement to assume that young Republicans view it the same way is a mistake. I think that young Republicans simultaneously really care about climate change and prioritize it, but at the same time, they have a lot of other issues that they care about. And the way that I see it interacting is that young Republicans are aware of the way that climate change intersects with national security, the way that it intersects with energy policy, the way that it intersects with if they're a religious person, maybe their faith or the way that it intersects with agriculture. And so they see it not as just this singular issue that they care about, but as an issue that impacts all of the other issues that they care about, that potentially make up their conservative DNA. And so I get the question a lot, you know, would a young conservative vote for a Democrat if the Democrat was better on climate? I don't think that's necessarily the right way to look at, at the landscape here because young Republicans are prioritizing multiple things and climate is one of those.

Austin Colón: Yeah, and I see that issue similarly for people on the left. I don't think it's a question between, you know, would they vote for the other party? It's more like, would they vote or would they just not vote, if the party doesn't take their needs seriously, and I've heard people say that if the Republicans don't take climate seriously, they could lose a whole generation not necessarily to the other party. But just maybe to apathy if anything, the movement that you've seen with the republican party on climate? Is there enough for that not to be the case anymore?

Danielle Butcher Franz: I think Republicans really have to continue to do better on climate change. Like I said, there's been a lot of positive evolution, but it's not enough. And that's not me saying that, that's voters saying that. There was actually a study that came out of CU Boulder recently that showed that for every, um, election cycle that conservatives are not talking about climate change in a productive way, they are losing half a percentage point of the electorate. And so what that means is that over the long term, if Republicans are not talking about climate in a way that meets voters where they are, they will become politically irrelevant. And again, that's not my opinion. That's what the data shows.

Austin Colón: In the grand scheme of things, you know, we want to get climate policy passed and move in a positive direction. We do need to find common ground with everybody, especially in Congress. So what do you think the best way is to find common ground with those on the left and the right?

Danielle Butcher Franz: Yeah, that's a really good question. And I think that's sort of the riddle that we're constantly trying to crack. Um, I think that what the left could do is not assume that Republicans don't care about these issues just because we may have a different vocabulary or talk about them in a different way. Something that I've seen both sides of the aisle really get hung up on is, you know, do you commit to 2050? Or do you commit to the Paris Climate Agreement? Like these sort of litmus tests that we impose on one another to gauge how serious someone is, I don't think they're necessarily productive. I think that that's kind of where the partisan divide starts to really show itself is when you give these litmus tests and say, Well, I can't work with you if you don't agree with this. And then for the right, what I would say is recognize the good that the left has done on the environment and the good ideas that they do have and talk about how to shape their ambitions into something that is more aligned with your vision. Um, because I think too often republicans want to throw the baby out with the bathwater and say, you know, because you're left of center, I just disagree with everything that you're saying, um, and they don't have to do that. They don't have to have that knee jerk reaction.

Austin Colón: Danielle Butcher Francis, CEO of the American Conservation Coalition. Danielle, thank you so much for joining us on Climate One today.

Danielle Butcher Franz: Thanks for having me, Austin.

Ariana Brocious: And that’s our show. Thanks for listening. Talking about climate can be hard, and exciting and interesting -- AND it’s critical to address the transitions we need to make in all parts of society. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. You can do it right now on your device. Or consider joining us on Patreon and supporting the show that way.

Greg Dalton: Brad Marshland is our senior producer; Our managing director is Jenny Park. Ariana Brocious is co-host, editor and producer. Austin Colón is producer and editor. Megan Biscieglia is producer and production manager. Wency Shaida is our development manager, Ben Testani is our communications manager. Jenny Lawton is consulting producer. Our theme music was composed by George Young. Gloria Duffy and Philip Yun are co-CEOs of The Commonwealth Club World Affairs, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.