Journey of a Former Coal Miner

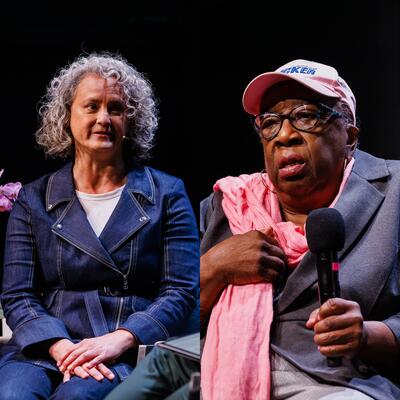

Guests

Nick Mullins

Audrea Lim

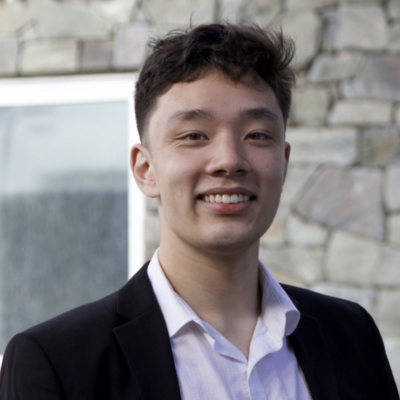

James Coleman

Summary

Nick Mullins is a former fifth-generation coal miner from Clintwood, Virginia and creator of the blog, Thoughts of a Coal Miner. Growing up, his father taught him to love the woods that surrounded them.

“He'd take me and my brother to the top of the ridge line, show us the trees. We would play in the streams. I really got really connected to nature that way,” Mullins says.

As a kid, Mullins says he had a lot of pride and respect for his forefathers who supported their family by working in the coal mines. But as he grew older, his views of the industry that employed his family changed. When he was 19 years old, a coal company opened a mine on the mountain above his family home.

“It devastated me,” he said. “They had just obliterated all the oaks and all the poplars and it didn't look like the same place. And then as the months continued, they started stripping away the top soils and it just became, as some people have said, like a moonscape.”

Mullins became an underground coal miner himself, because he says the “mono-economy of coal” meant there were few other options for a steady paycheck and good benefits. But he says that his experience of losing a natural place special to his family was one factor that drove him to leave the mines and become an activist against mountaintop removal.

He says he’s been frustrated by the biases on all sides of the issue, from wealthy and privileged outsider environmentalists and academics who presume to understand the working-class life of a coal miner to the same coal miner who responds to such activism with “anti-environmentalism, anti-intellectualism.”

His advice to the larger environmental groups is to provide money, resources and trust to local grassroots activists.

“Have faith that they can and will make change in their communities if they’re provided the resources,” he says.

Mullins is one of many grassroots activists featured in the book, The World We Need: Stories and Lessons from America's Unsung Environmental Movement.

The book’s editor, Audrea Lim, says the goal was to push against the tide of coverage focused on large environmental groups. Instead, she sought to highlight people often working in their own communities to combat pollution and build toward a cleaner and more equitable society. Lim says those efforts are diverse, from housing and gentrification to local food systems and sustainable businesses.

“The thing about grassroots activism, apart from the stereotype, is that it's really just people in a community who sort of see a problem — whether that’s refineries being built in their neighborhood or a community garden because they don't have access to food — and then they get together on their own and tried to find a solution to it,” Lim says. “It’s really as simple as that.”

Four years ago, James Coleman was a high school senior and climate activist in South San Francisco, an industrial city distinct from its more famous neighbor. Now he’s a city council member finishing up a degree in regenerative biology at Harvard.

He says he continues to see a lot of tension between science and politics, especially during the pandemic.

“I think it's really important that scientists speak out and say that, you know, these are undeniable facts, and these facts need to be taken as facts and not politicized by whatever's happening in the national discourse,” Coleman says.

Coleman says the combination of the racial justice movement in 2020 and the “dismissive” response from current city council to the concerns of him and other young activists motivated him to run for office. Now, somewhat to his surprise, he’s on the other side of the room.

“Growing up I never saw myself as an elected official. I always saw myself as an activist because that’s what I did in high school, that’s the role that I had as a college student. I always saw myself as someone who would be holding elected officials accountable, not necessarily being the one in office being held accountable,” he says.

Climate change is a big part of his platform. He says a lot of people are working to get more young activists into office, even though activists and elected officials play fundamentally different roles:

“A lot of activists can inform elected officials like [me] about the various issues that the community is concerned about,” Coleman says. “It’s their job to be idealistic, to have the vision, and it's my job to implement that vision and make it possible.”

Related Links:

Have you ever had a difficult conversation about climate? A disagreement, perhaps, or coming to terms with a new reality? We’d like to hear your stories. Please call (650) 382-3869 and leave us a voicemail about your toughest climate conversation. Or drop us a line at climateone@gmail.com. We may use your story in an upcoming episode.

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: What motivates the activists at the grassroots level? Climate One’s empowering conversations feature all aspects of the climate emergency. I’m Greg Dalton. Today we’re talking with local environmental and climate justice advocates about what drives them, and what the big-name organizations might learn from their work.

Greg Dalton: Nick Mullins is a former fifth-generation coal miner from Clintwood, Virginia and creator of the blog, Thoughts of a Coal Miner. He says growing up, his father taught him to love the woods that surrounded them.

Nick Mullins: He'd take me and my brother to the top of the ridge line, show us the trees. We would play in the streams. I really got really got connected to nature that way. (:10)

Greg Dalton: His family also hunted and fished there. Mullins says as a kid, he had a lot of pride and respect for his forefathers who supported their family by working in the coal mines. But as he grew older, his views changed. When Mullins was 19 years old, a coal company opened a mine on the mountain above his family home.

Nick Mullins: It devastated me. I wasn't really up on any of the fight against mountaintop removal coal mining. I remember whenever they first started logging hiking up to the top of the ridge and seeing what was left of landscape. And they had just obliterated all the oaks and all the poplars and it didn't look like the same place. And then as the months continued, they started stripping away the top soils and it just became and as some people have said like a moonscape. And they just chiseled away at the mountain. And it would never be the same again, only in memory.

Greg Dalton: It sounds like this is still upsetting for you even just to talk about those memories.

Nick Mullins: It is. You know, when people talk about a sense of place, I don't think people often think about how that place can be just utterly destroyed. And thinking about those kinds of things still bit of a raw emotion for me, knowing that me and my brother we’re the only ones or of course some other surviving family members are the only ones who are gonna be able to remember some of those places that no longer exist. And I won’t be able to show them to my children.

Greg Dalton: Coal miners are often portrayed as American heroes keeping the lights on fueling the Industrial Revolution. To what extent do you think coal miners see themselves that way as heroes powering the country?

Nick Mullins: They absolutely see themselves that way. I mean it's one of the things that kind of helps keep you going. Anytime that you’re having to face a difficult situation day in and day out and face such dangers as coal mining you certainly have to feel some pride in that what you're doing is good and worthwhile. It’s not unlike a veteran status to some degree. It’s that sense of sacrificing for you and your family and the nation at large.

Greg Dalton: You eventually became a miner yourself, why?

Nick Mullins: Well, it’s purely economical, you can really delve into a lot of history to contextualize the situation in Appalachia currently. But essentially the coal industry owns the majority of the region; they own the majority of the mineral rights under the ground. And so, there is a tremendous amount of power that they hold in terms of land ownership, economics and politics. So, the mono economy of coal that is in our region, it was created. So, there are really very, very few job alternatives in the region for anyone that wants to continue living there.

Greg Dalton: And you must've known you were taking personal health risks but how did you weigh the personal economic benefits and personal health risks?

Nick Mullins: I mean I really didn't weigh them out you just did what you had to do for your family. You try not to think about it too often and you did your best to stay out of the dust and not put yourself in the more dangerous situations. And once you get into the mode, you’re just doing what you have to do. And if you think about it too often it will scare you and make it difficult to go in the mine. So, you just work.

Greg Dalton: And at some point, you reconsidered your life, what prompted that?

Nick Mullins: Well, there was a lot going on. I was living in my great-grandparents old homeplace we’d inherited, had been fixing it up for several years and raising our kids in the same valley that I had been raised in, actually the previous several generations. And we lost it in the fire one night. It just was such a shock to the system everything that we ever had and had worked towards was just gone. I remember the night three nights later going back to work and just getting ready to go into the portal down to the darkness, and I just had asked myself, what am I doing, what's all this worth? And I don’t know, it just made no sense to keep risking my life whenever material things were so, what’s the word I’m looking for, can’t quite make it.

Greg Dalton: Fleeting or yeah, it’s the loss of --

Nick Mullins: Fleeting, yes, fleeting.

Greg Dalton: The loss of the family home made you reassess your life and your values.

Nick Mullins: Yeah. And it also made me think about how important life is. We were fortunate not to be home that night. And it just made me really think about how precious life is too and how important spending time with your children is. And a lot of different, lot of different things going to my head that made me just kind of wake up and realize that life is worth a lot more than working hours of overtime in darkness and risking your life and not knowing what the next day could bring.

Greg Dalton: I can see that, sure. So, you tried to leave a couple times and then eventually left for good. What made you start checking out environmental organizations?

Nick Mullins: My dad had been picking up this newsletter that was being published by a local environmental organization. And they were mainly talking about natural gas. But it was through them and documentary that was on Discovery Green that I kind of became aware of the issues with mountaintop removal coal mining and that people were fighting surface mining. I was never a big fan of surface mining which was one of the reasons I went underground. But I also had noticed that there were a lot of coal miners that were retired from the union mines who were involved in this fight, as well. And so, I saw a possibility of connecting between the labor rights movement and the environmental movement to try to get some justice in Appalachia.

Greg Dalton: And what sort of activism did you take part and how effective was it?

Nick Mullins: Well, the first I guess bit of activism that I got involved in was going to Appalachia Rising in Washington DC. It was a large event that was hosted by the Alliance for Appalachia in which they brought together a few thousand people to fight mountaintop removal with lobbying days and there was a march. I remember specifically, though the first plenary or gathering in which they were they had a panel speaking. They asked all the Appalachian mountain people to stand up that was in the room. And of course, I stood up with my family and then I looked around and there was only seven or eight of us in the room of probably 300 or 400. And I was like wow there's a lot of support here to help stop this that is great and it was very empowering. We marched to the White House and people sat down in front of the White House and refused to move in acts of civil disobedience. And I was just kind of watching the Capitol Hill law enforcement, I said, I guess this is just another day isn’t it? You all see this a lot it’s like every day. That’s whenever I was thinking to myself is this really going to have an impact because somebody is here every day doing the same thing or some similar for different cause is this really beneficial to actually fighting mountaintop removal.

Greg Dalton: Do you think that an individual can have an impact on something bigger than themselves?

Nick Mullins: That's always the hope. I believe that there are always going to be people who can do well at organizing. I think back to the union miners including my great-grandfather. And they were up against you know tremendous odds. During those days, it wasn't uncommon for the coal companies to hire mercenaries to defend their coal mines and to bust the union. And that started with people just coming together under a common cause and understanding that they were being exploited. They were being oppressed and that they had to fight for the common good. So, I believe that an individual still has the capability of bringing people together and uniting across those lines that can help really spur a movement that's necessary to get us beyond all these fossil fuels. But that person also has to connect with other people and it has to grow. It can't be just one person.

Greg Dalton: It sounds like you're talking about a linkage between sort of the labor movement and the environmental movement that there’s — you’re acting like your forefathers in a slightly different way.

Nick Mullins: Precisely. Whenever it comes to, you know, I mean traditionally, the fossil fuels industry has been abusive towards employees. And most extractive industries have been abusive towards their employees with long legacies of workplace safety issues as well as issues in pay and long-term health care benefits. And these are all things that are very closely linked to what environmental activists are looking for as well. The environmental justice movement I feel at least those that are closer to the working-class families or who come from working-class families, especially the grassroots activists understand that the environmental justice movement should be more about system change and that all aspects have to be changed before we can really start to work towards cleaning up the environment and stopping these industries.

Greg Dalton: A lot of the connectedness that we talk about on Climate One. You write about the stereotype of environmental activists as "over educated tree huggers from way the hell away from here." How did your neighbors and former coworkers look at you when you became an “environmentalist?”.

Nick Mullins: Well, they didn’t like me very well. I was called a traitor and I think people hated me even worse than they did a traditional environmentalist because they saw me as having gone to the other side.

Greg Dalton: Betrayal within, yeah.

Nick Mullins: Yeah, definitely. But over time once they realized that I had their interests in mind and I kind of began to speak against some of the things that the environmentalists were doing wrong in the way that they were portraying coal miners, then I was able to mend those bonds and regain the respect of a lot of my friends.

Greg Dalton: As you note a lot of support for change in Appalachia comes from outsiders. How critical is your credibility and experience as an insider literally inside the mines for affecting change with environmentalists?

Nick Mullins: I don't know I often get the feeling that although my voice is appreciated and that people say that I have a powerful voice, I don’t think it really goes too far outside of that. The Sierra Club had an opening for a campaign organizer in Eastern Kentucky for the Beyond Coal Campaign. And at the time I was like, wow, this would be a great opportunity. I can talk with coal miners. I can help start to mend some of this. So, I interviewed for the position and then was later informed that I didn't get it. And several years later I found out that one of the primary reasons was I didn't have a college education. I didn't have a diploma or a bachelor's degree. So, yeah that bothered me quite a bit. And I had some friends advocating for me within the organization. And I've also seen the way that some of these large organizations tend to use grassroots activists’ voices, but whenever it comes to giving them employment or full-time, you know, benefited positions, they often just give them small-scale grants and stuff that barely keeps them going. Nothing that you could count on for a living wage for any sort of job security. So, it makes it difficult and ultimately the grassroots environmentalists have to fall back and be concerned more with their own personal ability to survive and take care of their kids than they can to actually fight the good fight a lot of times.

Greg Dalton: I’m talking with Nick Mullins, a former fifth-generation coal miner from Clintwood, Virginia and creator of the blog, Thoughts of a Coal Miner. Coming up, we’ll continue our conversation, and we’ll hear more examples of how grassroots activism can effect change at the local level.

Audrea Lim: There are communities all around this country that have been thinking through piecemeal solutions to these problems for a really long time actually.

Greg Dalton: Sharing the lessons from grassroots work. That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. We’re talking about what we can learn from the grassroots side of the climate and environmental movements. Nick Mullins is a former fifth-generation coal miner from Clintwood, Virginia and creator of the blog, Thoughts of a Coal Miner. He’s now an environmental activist. He’s written about what he says is quote “the unfortunate nature of the nonprofit, academic and activist industrial complexes that overtake actual grassroots justice work.” I had never heard of the nonprofit, academic and activist complex and asked him to explain.

Nick Mullins: In my experience working in and out of activist organizations and working in academia, I’ve seen a lot of privilege unfortunately, that makes it difficult to connect with the people of these areas that are being the most impacted by environmental issues and environmental injustices. Within these organizations we have a lot of people who were running them and who are being paid salaries and living in very nice areas of the nation who never really came from any kind of similar background as say someone who grew up in Appalachia and who were first-generation to go to college. That breeds an unfortunate disconnect I feel with the people. So, unfortunately what I've noticed is that they will use local grassroots activists’ voices and the struggles that people are fighting and they’ll back them and then they’ll create a huge amount of media about it, especially in terms of gaining donations to help fight these battles. But whether or not that money trickles down to the actual grassroots activists fighting these battles is often questionable from what I've seen.

Greg Dalton: So, there’s a certain arrogance or elitism that you’re talking about from people who think they know best with good intentions but they don't know the local area.

Nick Mullins: Yes. And I think a lot of that falls back on rural-urban divides. And a lot of the political divide that’s going on in our nation. I mean if we really think of, in terms of the economy and how things work. If you are a working-class citizen. If you are a coal miner, you're typically paid a lot less than somebody that went to college. And so, the narrative in our nation is get a degree so you can go on and get a better job so you don't have to work outside and you don't have to face all these terrible realities that the working class is having to face. And so, conversely, those who aren’t able to succeed who aren’t able to go on to college either because they lack the funding or they grew up in a school system that doesn't do well to promote students to go to college, they feel as if they are lesser people. And so, you have to find some way within yourself to feel pride and to feel dignity. And so, a lot of the times that comes out as anti-environmentalism, anti-intellectualism. Sadly, that also has created within academic circles and within a lot of organizations, a kind of downward looking at the people in these communities. And they don't understand it is reactionary to their privilege and to the fact that they were able to succeed in ways because they already had resources handed to them.

Greg Dalton: So, what can grassroots activists do that the national or big organizations can’t?

Nick Mullins: They can communicate with their local people. They know what it's like to live in these situations. Because they live in the community. And so, it makes it so much easier for them to be more persuasive. And in cases like Appalachia where we've had people, outsiders come in first take over mineral rights and then make us work terrible jobs. And of course, the media who came in in the 60s and portrayed our poverty in a negative way without contextualizing why we were in poverty. We have this real outsider stigma. So, whenever more people come in to try to tell us how we should live and that we’re doing something wrong. It really strikes at those issues. And that goes for so many other communities out there.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, trusted messengers are so important. So what would be your advice to big environmental elitist organizations. Clearly, they have a role to play; they do have tremendous power and success. But what would be your advice to them?

Nick Mullins: My advice would be to do as much fundraising as you need to do, but you need to make sure that those funds get down to the grassroots level and that you don't need to micromanage grassroots activists. That we need resources just as much as anyone else to be able to support our families and do this important work. And that as much as you may understand the situation and that you might have read sociological work about the region and the people, and you may be woke to all the issues that we’re up against, you still haven't been able to walk a mile in our shoes. And so, it's going to be extremely difficult for you to be able to do any kind of positive work. You have to rely on the grassroots people, and that means humbling yourself a great deal. Having faith in those people and communities who may not hold a college degree, who may not see everything the same way that you do, but have faith that they can and will get, you know, make change in their communities if they’re provided the resources.

Greg Dalton: Thank you, Nick Mullins. Appreciate your time, sharing your story.

Nick Mullins: Thank you.

Greg Dalton: Nick Mullins is a former fifth-generation coal miner from Clintwood, Virginia and now an environmental activist.

Greg Dalton: Mullins is one of many grassroots activists featured in the book, The World We Need: Stories and Lessons from America's Unsung Environmental Movement. The book’s editor, Audrea Lim, says the goal was to push against the tide of coverage focused on large environmental groups. Instead, she sought to highlight people often working in their own communities to combat pollution, and build towards a cleaner and more equitable society. Lim says those efforts are diverse, from housing and gentrification to local food systems and sustainable businesses. The book features the work of three dozen such activists, but I asked Lim if she could tell us one story that really stayed with her.

Audrea Lim: There are so many good stories in here. My favorite one or the one that really stuck with me and actually gave me a lot of hope is based in Hawaii. And it's an interview with this man Eric Enos. He's native Hawaiian, but he grew up with very little knowledge of his native Hawaiian culture like including the central importance of taro. It’s this purple root vegetable that mostly like --

Greg Dalton: It’s delicious. I love it.

Audrea Lim: But it’s very important in native Hawaiian culture which, you know, was suppressed under US colonialism. So, Eric, he began teaching art to native youth gang members, and he also took them hiking in the back of the Waianae Valley which was basically just dried up and that was where the gangs, the syndicates would dump bodies and stolen cars basically. And while they were sort of hiking and camping there, they found these like just walls and just terraces in the ground. And these sort of like clearly cultural sites, but they had really no idea what they were. So, Eric knew that the Bishop Museum, they had some archaeologists there who, you know, white archaeologists who were environmentalists, and he knew they would be sympathetic. So, he went and asked for their help and they sent some of their experts who found that you know the entire area was once actually under taro cultivation. But, you know, the water in the back of that Valley had been diverted towards the colonial sugar plantations like a long time ago. So, then he went and appealed for help from like a State Senator and local agencies who then sort of gave him and his youth some guidance and help and funding to sort of build a new irrigation system and so they all began growing native plants.

They had been basically alienated from their own culture they had been told that this was like that you know this was a culture that was like backwards and uncivilized all their lives. And they discovered by sort of learning to farm in the back of the Waianae Valley they learn about the land their own culture and also about the taro in the process. So, I mean, the reason that I really like this story and sticks with me is I mean it's really touching but it also shows how I guess lots of different kinds of institutions and people from different communities and backgrounds can collaborate and come together to support this like very tiny community to build like a very different you know just more equitable and more resilient future.

Greg Dalton: Right. And relying on each other and sharing and I'll help you here you help me there. It’s not all about a commercial or financial transaction. One of the people you’ve feature, Bernadette Demientieff, is Executive Director of Gwich’in Steering Committee in Alaska says she's always had to straddle two worlds. “One that's being pushed on us and another we’re trying to protect.” Do you see a difference in approach with activists whose way of life has been under attack for generations, indigenous and black people from those where their threat is newer and more sudden?

Audrea Lim: Yeah. I mean there definitely is a difference. I think for communities like Bernadette's, and also, with somebody like Eric Enos, the native Hawaiian activist who grew up, you know, with very little connection to his land or culture. When you sort of grow up with that sort of, I guess identity it's really not just one thing it's that you're like generations and generations of your ancestors as an indigenous person in America, you know, been repeatedly pushed off your land and had your land stolen from you repeatedly. And then there's histories of you know native kids being sent to schools where they are taught that they need to you know, forget about everything their entire culture that they shouldn't speak their language, that they should, you know, hate the things about them that their families probably really treasured. You know the culture, food. And it's yeah, it's cumulative.

Greg Dalton: Like trauma. What I hear you there’s intergenerational trauma. The people who experience that generation after generation and people of color, indigenous people know that and live that trauma. You write that many groups and activists have understood for decades that pollution and environmental destruction besiege their communities, pipelines, factory farms, dams where those are symptoms of America's deeper dysfunctions. One thing that jumped out of me in your book is the Cerrell report commissioned by the California Waste Management Board which actually put in writing that waste facilities should look for low education communities open to exploitation who don't speak English and are Catholic. We often know that to be true, but it's not common to my knowledge that organizations actually put it in writing so explicitly.

Audrea Lim: Yeah. I mean, and this is something that has like a very long history in America. I mean --

Greg Dalton: Again, not new but yeah still startling to see in writing.

Audrea Lim: Yeah, I mean the Cerrell report I think is from the 80s. And even from before the US was a country, you know, British companies, colonial companies would come and they felt completely fine going into areas that were, where there were thriving indigenous societies and economies and just chase them out or mine their gold for really similar reasons. And yeah that continued to be the case.

Greg Dalton: My guest is Audrea Lim... For many people, the term grassroots activists conjure images of small bands of angry people raising their fists with megaphones. Your book also includes examples of activist art and other kinds of power accumulation. Talk about citizen science as a form of activism. How are there different ways of being an activist?

Audrea Lim: I mean I think the thing about grassroots activism actually apart from the stereotype is that it's really just people in a community who sort of see a problem whether that’s, you know, like refineries being built in their neighborhood or you know they want a community garden because they don't have access to food and then they get together on their own and tried to find a solution to it or to you know fight off the corporations that are trying to come into their community. It’s really as simple as that: grassroots activists can be you know mothers and grandparents, you know, who are concerned about these kinds of things or yeah scientists in the community. And so, you know, grassroots activists can also use just a range of different tools.

Greg Dalton: Collecting data can make you an activist who doesn't have to be that stereotypical shouting. You can collect data with an application and that can be an activist.

Audrea Lim: Yeah. And, you know, and there are activists in the book who came together to try to pressure all the different dollar stores to I just stop selling products in their dollar stores that had toxic chemicals. And one thing that the activists there talk about - these are very small, very small grassroots farmworker or just like little citizens groups in these poor communities. And some of them had been doing a lot of these like protests and just activists work in their communities. But one really important turning point for them was when they just linked up with some of these bigger, better resourced groups who had access to scientists and just the resources to be able to fund these scientists to go and like test all these different products and actually generate data on what chemicals actually were in all of these products. And then, you know, to be able to bring that data to big funders and to politicians and to shareholders meetings and to be able to pressure these much bigger institutions.

Greg Dalton: So, there are benefits of scale and resources that the large organizations bring. The subtitle of the book, The World We Need is Stories and Lessons from America's Unsung Environmental Movement. What are some of the biggest lessons you hope readers will learn from the book?

Audrea Lim: The climate crisis just feels like this really big, almost unmanageable thing that you know there's a lot of despair around how we’re gonna tackle this problem that seems to require like really changes to everything around us. And, you know, it is obviously a very daunting challenge, but one thing that I hope that readers will come away from this book with is that there are different there are communities all around this country that have been thinking through piecemeal solutions to these problems for a really long time actually. And so, yeah, I think one of the lessons is that I hope people will take away from this is that yeah there’s still hope.

Greg Dalton: We can do it. Audrea Lim, thanks for coming on Climate One, appreciate your time.

Audrea Lim: Thanks.

Greg Dalton: You're listening to a conversation about grassroots activism in the climate movement. This is Climate One. Coming up, we hear from a young activist turned city council member.

James Coleman: I always saw myself as someone who would be holding elected officials accountable, not necessarily being the one in office being held accountable. So it was definitely eye-opening. (:10)

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. We’re talking with grassroots activists about their role in the environmental and climate movements.

Greg Dalton: Environmental contamination from fossil fuels or heavy industry can leave a long legacy in a community, often in the bodies of residents. San Francisco’s Bayview Hunters Point neighborhood is one such place. Climate One contributor Daphne Young brings us the story of an advocate who is carrying on the legacy of her activist mother by creating a foundation to spur on the next generation to push for clean neighborhoods.

[Start Playback]

Arieann Harrison FEATURE (4:05)

[End Playback]

Greg Dalton: Four years ago I interviewed a young climate activist named James Coleman. At the time, he was a high school senior in South San Francisco, an industrial city separate from its more famous neighbor. Now he’s a city council member. I invited him back on Climate One, and we started by listening to a clip from our conversation in 2017.

[Start Playback]

James Coleman: I'm an aspiring scientist. And as scientists we see that they stick through labs they stick to their science. They're not really out in the political world. But right now, we’re seeing that politics and science are merging together and that scientists have to be a voice in our society. They have to get out, they have to tell us what the facts are and how we should use our policy to fight climate change.

[End Playback]

Greg Dalton: So, you're studying regenerative biology at Harvard, but now you're also the youngest member of the South San Francisco City Council. Have your views changed about the balance of science and politics?

James Coleman: I feel like I've just throughout my college career I’ve kind of done what I said in that clip where I did pursue science. I am majoring in biology. I have been working in a lab for the last three years until the shelter in place. And despite spending much time in the lab I still found time to be involved politically and with the issues whether it be on campus in Boston or here in my own community.

Greg Dalton: So, how do you see the interaction between politics and science? Because some people would say science shouldn't be political; it’s been politicized in this country, you know, just facts in politics. How do you see that interaction or the tension between them?

James Coleman: Yeah, I think there’s a lot of tension. I think especially with COVID there’s a lot of tension between the science community and politics. I think the pandemic has been politicized unfortunately, through the Trump administration. And we’re seeing the impacts where folks aren’t wearing masks, where folks are refusing to vaccinate. It's not based on any hard science. So, I think it's really important that scientists speak out and say that, you know, these are undeniable facts, these precautions and these facts need to be taken as facts and not politicized by whatever's happening in the national discourse.

Greg Dalton: So, when you were in high school you were a fellow at the alliance for climate education, an educational group of course presented to high school students around the country. Now you’re a senior at Harvard you’ve been an advocate for Fossil Fuel Divest Harvard, and a cofounder of the Harvard Undergraduates for Environmental Justice. You seem so busy, how do you do it all?

James Coleman: I try to find time and you know I do overbook myself I feel but, you know, it’s like I think it’s easier when you have a passion and when you love what you're doing. And when you see the impact of climate change and what the world can be if we transition to renewable energy economy. If we change our political systems, if we believe in the science and fight for the world that we all know is possible. And so, a lot of what I do I don't really consider work. I consider it you know a passion of mine that these issues need to be addressed. They need to be addressed equitably and in a way that does not leave any community behind.

Greg Dalton: For people who don't know, how would you describe the city of South San Francisco?

James Coleman: I would describe it as very diverse, very working-class and there’s a lot of science in South San Francisco. So, we’re once called the industrial city; we still are, but now I think a more suitable name would be the biotech city. Because we are right now the biotech capital of the world and we have tens of thousands of jobs, you know, biology and pharmaceutical jobs.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, there’s a cluster of office parks between San Francisco and the San Francisco airport. Lots of biotech firms there. Walk me through the process. You’re a student at Harvard but your shelter in place you're studying remotely in your home in South San Francisco. And how do you decide then to, hey, I’m in college but I think I'll run for the city council. How does that happen?

James Coleman: It’s really weird because the pandemic is what allowed me to run for office and also serve while still finishing up my studies at Harvard. And so, a bunch of friends that I graduated with from high school and I, we started going to school word meetings and city council meetings and trying to see what was going on in our home community. And then we saw that the murder of George Floyd happened in late May and we are all taken aback by that. And we saw that our home community of South San Francisco was no stranger to its share of police violence. When we went to our city council and we were asking for change we’re asking for accountability. The way the city council, the old city council responded was to many young people who are getting involved in local politics for the first time they were responding dismissively and condescendingly. And when I saw that there is this disdain for the youth community who was demanding change that I saw that we need to hold our elected leaders accountable.

Greg Dalton: Did the political establishment take you seriously, how do they treat you at first as a college candidate?

James Coleman: Well, yeah, they didn’t treat me too seriously at the beginning. But I think all it really takes is a conversation for someone to know that you're seriously is that you care about the issues that you're fighting for the right things. We ran a campaign that was grassroots. We didn’t knock doors because of the pandemic but we did lots of fire drops throughout the district. We made probably 17,000 phone calls and we raised money primarily through small dollar donations and we’re able to outraise the incumbent and have an average donation that was 10 times less than my opponents. And it just goes to show that, you know, with people power you can beat the political establishment and run on a campaign with an unapologetically progressive campaign in that.

Greg Dalton: How often did you talk about climate during your campaign?

James Coleman: Very, very often. Remember in San Francisco, it was last September where we had that orange Wednesday where the skies were all orange and that scared a lot of people. Like is this the future? Is this the Blade Runner future that we’re looking at here is this going to be the status quo? And I think that rightfully scared a lot of people, including myself. And I saw that, you know, our city could be doing so much more to address climate change through reach codes to requiring all electric buildings and electrical appliances to where he can make that transition faster.

Greg Dalton: So, what was it like as a 21-year-old going into your first online meeting as an elected official?

James Coleman: It was interesting. It was definitely surprising because I never, you know, growing up I never saw myself as an elected official. I always saw myself as an activist because that’s what I did in high school, that's the role that I had as a college student. I always saw myself as someone who would be holding elected officials accountable, not necessarily being the one in office being held accountable. So, it was definitely eye-opening and even sometimes today, these days I just sit here thinking like am I really a council member, you know, doing these things and trying to fight for these policies.

Greg Dalton: What's it like being on the other side now?

James Coleman: It's much different. You know, there are certain things you can say as an activist and certain things you can't say as an elected official. And so, I've had to, you know, change the way I conduct myself publicly because I'm not just, you know, I’m not representing like an active organization, now I’m representing the city of South San Francisco. And I need to make sure that, you know, how I am like benefits the people of South San Francisco doesn't harm anything in any way, relationship wise and also with other institutions. And I’ve also seen that there's a lot of bureaucracy involved there's a lot of interaction between state and local and federal politics that a lot of people and policies that a lot of people don't realize and that some things you can do at the local level some things you can’t. And, you know, one thing would be like qualified immunity that’s not something you can do at the local level that’s a state and federal level thing. But with reach codes and --

Greg Dalton: What are reach codes?

James Coleman: Reach codes are building codes that go beyond state regulation. For example, would be like requiring all-electric buildings or banning new construction that includes natural gas, requiring more electrical vehicle chargers in new construction - things like that that basically go beyond state requirements and that local cities can pursue that can really be an example for other cities to follow and for the state to eventually adopt in the future.

Greg Dalton: So, when you talk to your neighbors, now constituents. How do you talk about climate and things tangible relative to their lives?

James Coleman: I think a lot of people are now kind of shocked and scared about the annual wildfire season that we have in California now. Growing up my entire life there never really was a wildfire season where we had weeks of polluted air that was hazardous to breathe. But ever since I believe it is 2018 or 2017, we’ve been having annual wildfire seasons where classes have been canceled where you have ash in the air for weeks at a time. And we have so many homes being destroyed because of climate change intensified while -- and I think people they realize it’s not the community I grew up in. They don't want this to be just this cyclical and that’s something needs to change. That means changing the way we conduct our system of energy and making it more renewable and more sustainable.

Greg Dalton: Youth are really pushing the climate conversation and pushing people in power and, you know, there’s a lot of resentment even at the baby boomers and what they've done. I'm curious about what the reaction has been of some of your peers to you going into elected office.

James Coleman: I think a lot of folks are inspired and they want to see more activists in office they want to see more youth in office. More Gen Z, we’re not talking about millennials anymore we’re talking about the zoomers and having them take over. And, you know, it’s not everyone, as you know some people want to stay in the activist position they want to continue and that’s just how they see their role as, right. But I think that the institutional knowledge from being a city council member from being on the inside I think that that can help inform more activists. And a lot of activists can inform elected officials like I, like I am, about the various issues that the community is concerned about the changes that they want to see. It’s their job to be idealistic to have the vision and it's my job to implement that vision and make it possible.

Greg Dalton: James Coleman is a member of the City Council of South San Francisco and a senior at Harvard studying human development and regenerative biology. James, thanks for coming on Climate One.

James Coleman: Yeah, thanks for having me again.

Greg Dalton: You’ve been listening to Climate One. We’ve been talking about the environmental and climate movements and what we can learn from those pushing for change within their own communities.

Greg Dalton: To hear more Climate One conversations, subscribe to our podcast on Apple, Spotify or wherever you get your pods. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. It really does help advance the climate conversation. Let me know what you think about the show by emailing me at greg at climate one dot org.

Greg Dalton: Brad Marshland is our senior producer; Ariana Brocious is our producer and audio editor. Arnav Gupta is our audio engineer. Steve Fox is director of advancement, Kelli Pennington directs audience engagement and Tyler Reed directs our operations. Dr. Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.