Gina McCarthy on Cutting Everything but Emissions

Guests

Gina McCarthy

Umair Irfan

Summary

The Trump administration has been intent on eliminating or rolling back a huge number of environmental laws and regulations that have existed for decades. While every new administration wants to change things, the pace and scale of this president’s actions have been staggering, says Gina McCarthy.

“ I really have never seen the laws themselves be dismissed and broken in such a cavalier way.”

McCarthy was the EPA administrator under President Obama. Her work included tightening rules on mercury pollution, improving drinking water quality and setting the first national standards requiring fossil-fueled power plants to cut emissions – all of which are now under threat. Under President Biden, she served as the first White House National Climate Advisor and head of the Climate Policy Office.

As the new administration began to target environmental rules of all kinds, McCarthy and two other former EPA administrators, Christine Todd Whitman and William K. Reilly, were spurred to write a joint op-ed alerting the American public to the dangers of such actions.

“I found it frightening and amazing that people would wanna turn that clock back like we saw happening,” McCarthy says. “We all knew that we had to stand up and explain that the environment isn't a partisan issue.”

Lee Zeldin, the new head of the Environmental Protection Agency, announced cuts to more than 30 of the agency’s cornerstone regulations, including “reconsideration” of mercury and air toxics standards, mandatory greenhouse gas reporting program and wastewater regulations for oil and gas development.

McCarthy says Zeldin is abandoning the agency’s foundational priorities in favor of promised economic gains.

“They changed the mission [of the EPA] from protecting health and the environment to – boom – all of a sudden, that doesn't matter and our job is to actually move fossil fuels forward,” she says.

The administration is also seeking to hollow out and privatize the agencies that provide essential public information on climate conditions and even weather forecasts, like the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Umair Irfan is a reporter at Vox who regularly interviews NOAA scientists and has been covering the Trump administration’s attack on the agency. So far, at least 880 NOAA staff have been laid off, and the agency has announced that they're seeking to eliminate another 1000.

“NOAA is housed in the US Department of Commerce, and so a big part of its mission is looking out for industries that are directly affected by things like weather, by climate, by changes in the atmosphere and our understanding of the oceans as well. So that includes fisheries, shipping, air travel, farming,” he says. “So a lot of critical industries in the U.S. depend on the foundational research done at NOAA.”

He says Americans will lose out from the cuts to such an important research agency that supports critical weather, climate and economic forecasts.

“If you lose that source of public information, it makes it much harder for people to get valuable information in those circumstances when you have a hurricane barreling towards the coast, when you see a major storm coming, when you are anticipating wildfires.”

This episode also includes a news feature reported by April Ehrlich of Oregon Public Broadcasting.

Resources From This Episode (6)

Full Transcript

Note: Transcripts are generated using a combination of automated software and human transcribers and may contain errors. Please check the actual audio before quoting it.

Ariana Brocious: I’m Ariana Brocious.

Kousha Navidar: I’m Kousha Navidar.

Ariana Brocious: And this is Climate One.

[music change]

Ariana Brocious: The news has been a lot to process and keep track of lately. The Trump administration has been like a bull in a china shop – intent on shattering, eliminating or rolling back SO many of the rules, policies and norms we’ve had for decades.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah. Of course all new administrations want to change things – but this is decidedly not normal. There is usually a sense of respect for legal precedent. Not this time.

Ariana Brocious: Right. Empowered by President Trump, Elon Musk’s team has been laying off thousands of federal workers across the government. And they seem intent on hollowing out the very core of government functions that protect all of us from all kinds of things – like pollution, fraud, disease, the list goes on.

Kousha Navidar: And notably, in spite of all these cuts to personnel, budgets, and regulations, one big thing we’re not cutting are the emissions that are overheating the Earth.

[music cue]

Ariana Brocious: Maybe it’s hard to relate to the work that some of these government officials do. It’s easy to imagine faceless bureaucrats in drab buildings, pushing paperwork and slowing things down. But the truth is many federal workers are dedicated professionals — people who take pride in providing essential services to the rest of us. The work of many agencies undergoing cuts is fundamental to keeping all of us safe, healthy and economically sound.

Kousha Navidar: You know, my mom is an environmental engineer specializing in water. She used to work for New York State, so not the federal government, but the work was similar. One of my first memories of going to work with her was that she gave me a stack of envelopes to lick. I was a loud kid and I’m pretty sure she was just trying to keep me quiet. I doubt she was even going to mail the envelopes. But I remember her coming home and telling us stories of her days in the field, arguing with real estate developers and designing big structures to protect water quality. And I knew that was really important.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah. That’s the kind of work we need people to be doing. Our first guest today is Gina McCarthy. She was the EPA administrator under President Obama. Her work there included tightening rules on mercury pollution, improving drinking water quality and setting the first national standards requiring fossil-fueled power plants to cut emissions - all of which is now under threat. Under President Biden she served as the first White House National Climate Advisor and head of the Climate Policy Office. She is a climate rock star.

Kousha Navidar: She has a long and illustrious career in the government that’s been dedicated to protecting the environment and public health. And just like my experience as a kid watching my mom influenced how I see the work of government, I wanted to jump back to hear how her childhood experiences shaped that career path.

I wanna start this interview talking about, uh, tarballs. 'cause I'm very interested–

Gina McCarthy: You know, that was top of my agenda as well.

Kousha Navidar: Oh, wonderful. Great minds think alike, I guess. You grew up in Boston, and I've heard, pray tell, of the story of you having tar balls stuck to your legs after you were swimming in the Boston Harbor. Right? I wanna ask how does that kind of firsthand experience with pollution influence your work?

Gina McCarthy: Two things I think, maybe three led me to really focus on environmental work. the first one was I, when I was a kid, we'd be driving in our old Chevy, I think it was going by some of the big textile factories in Lawrence and Lowell and those areas. And, you know, I'd go by and we'd be guessing at what color the river was gonna be that day. Which is not normal, but whatever they were producing, for clothing, all of the color was lighting up the Lawrence River and to me startlingly beautiful. And the older I got, the more I realized that's not beauty. That's the beast, right? And you know, the same thing with the tar balls. I knew it wasn't normal, but we were kids and that's all we had. And if you look at it from that point on, you know, I started when I was 26 after getting a master's at Tufts and a bachelor's at UMass in Boston. And my first real job, where you got money associated with it, wasn't when I waitressed as a kid because my mother took that money, it was, when I went to local communities and did some public health work and some environmental work, I was the public health agent in those days. It was amazing what you learned and what you saw at that point. There was so much work to be done and so few choices to choose from. And so that was my start of 40 years in government and actually more than that, but I. Hate to admit it.

Kousha Navidar: What do you mean about choices? There are so few choices to choose from. What do you mean?

Gina McCarthy: You know, we didn't have new technologies, we didn't have laws on the, I mean, this was when the laws were actually coming into being the environmental laws. We didn't have those, you know, you knew what was wrong, but what could you do about it other than to, you know, have them be considerate of their neighbors, you know, that wasn't gonna cut it. And so, you know, I grew up sort of inventing rules as I went, you know, at the local level I did all kinds of rules because we needed them. I used to charge people if they threw their trash out, if I found out who it was, and you left a letter in that little bag that you threw out, I was tracking you down, you know. But we also had, you know, at that point in time,Tobe Deutschmann was a company that dealt with PCB capacitors and they would take the oil that they had used for manufacturing capacitors that go on your electricity lines right on the poles and dump them in barrels down behind there. And I was the one driving, you know, the Department of Environmental Protection in Massachusetts. Just crazy telling them, you gotta clean this, you gotta find this guy, you get to do this. And we did that eventually, but I was the one going to local courts trying to get, you know, action happening. And, and so it became a fascination for me not to go after or be nasty, but to recognize that, you know, human beings didn't have limitations like we have today. And without those limitations, there are folks that do the right thing and there are folks that don't. And so, my job became, how do you track that down? Where's these gaps in the system? What are the laws you need locally and at the state and the federal level to really begin to protect people in a way that captures what we know from a science basis? So for me it was, you know, never about being mean. It was always about protecting.

Kousha Navidar: And about like just drawing on the experiences that you had.

Gina McCarthy: The way in which I thought about things moving forward for many decades.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah. Well, let's go forward, some of those decades to, today when so many of the rules that you and others have kind of written have come into play and, and been threatened. I mean, you wrote an op-ed with two other former leaders of the EPA. William Reilly who led the EPA during George HW Bush's administration, and Christine Todd Whitman, who served under George W. Bush. You, of course, were under Obama. So the op-ed is from bipartisan messengers. Tell us about that op-ed. Why are the current administrator's actions sending up red flags across party lines?

Gina McCarthy: You know, I saw things being proposed and happening that I never thought I'd ever see, you know, the diminishment of our ability to, you know, enforce regulations. And I mean, I found it frightening, and amazing that people would wanna turn that clock back, um, like we saw happening. And that was a particular moment for the three of us. I think Bill Reilly might have called me first, and I called Christie Todd Whitman, and we just started to talk about it because, you know, you are talking about three people that really I, I think, have never been in a position of wanting to be partisan about the work we did, right? It was never Republican against Democrats ever. Now, it got partisan in the Congress a lot, but you just sort of roll through those punches. You do your work as way you're supposed to, and we were really shocked by. What we saw as a rollback of, of really important environmental rules and, we needed to take a stand then, and they were all in from the moment we started talking, and that's because we all cared about it. We all knew that, that we had to stand up and explain that the environment isn't a partisan issue. That we had to stay strong and move it forward, and it was sad to have to write it, but it did, you know, I think raise a lot of eyebrows and get a lot of attention, for people who should know better and people who don't know anything and wanna engage.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah, I think it's interesting. You used the word sad to have to write it. How did it feel compared to some of the other work you've had to do? Because partisan politics are always a part of working in politics. Did this time feel different to you?

Gina McCarthy: Oh, absolutely. Yeah, absolutely. Look, I would never make the claim that Republicans thought I was a lovely human being, uh, when I was at EPA or the time I was in the White House. That's not my claim. but I really have never seen the laws themselves be dismissed and broken in such a cavalier way. So it wasn't really just about EPA, but it was about the attitude of this administration and what they thought they had the latitude to do with no science underpinning it, and no legal basis to make changes or to raise questions.

Kousha Navidar: I think the word cavalier that you used is key there. Let's talk about those cuts a little bit. The new EPA administrator, Lee Zeldin, announced 31 actions designed to cut regulations. So in response to those proposed cuts, your op-ed contains the line, “We fear that such cuts would render the agency incapable of protecting Americans from grave threats in our air, water, and land.” For you. I'd be so interested to know, are there cuts that you are most worried about, things that are top of mind for you right now?

Gina McCarthy: Wow. There are many of them. I think the ones that I was looking at in the particular list that Lee Zeldin administrator Zeldin put in, you know. It was 31 rules that, some of which have stood the test of time since 2009, right? 2012. These are longstanding, well-defined opportunities to, to really resolve pollution issues that are so important to human beings. Nevermind costs, nevermind anything. Costs are integrated into it in a way that makes it the least possible cost in all of those rules for moving forward. So I think the endangerment finding was clear. You know, that was one of the first I looked at and the endangerment finding was the 2009 decision by the Supreme Court that indeed climate change was threatening our health and welfare. So this is part and parcel of the president's basic agenda to say we are no longer going to agree that there is such a thing as climate and our goal has to be to advance our dominance over energy, AKA fossil fuels. So that was the announcement that that administrators Zeldin made was that was EPAs new mission. It wasn't just about these 31 rules. They changed the mission from protecting health and the environment to boom. All of a sudden, that doesn't matter and our job is to actually move fossil fuels forward, which is, you have to understand the people at EPA, this is an anathema, not just to the way we're supposed to work, but it is an anathema to the way we think.

Kousha Navidar: Well, I want to talk about those folks at the EPA in a second. It is so striking to me how you're talking about, listen, it is, it is the 31 cuts, but it is the ethos of the EPA as well that was very frightening and, and sad, right.

Gina McCarthy: What I think perhaps, the president doesn't know and it could very well be the challenge for Zeldin is that we were talking about rules being, basically re-looked at and we're talking about ones like mercury, you, mercury and anti toxic standard, which is it. So do you wanna have kids actually ingest mercury through eating fish? Is that what you want? Is that, you know, and of course it isn't, but the thing they haven't yet expressed in a way that makes sense to me is that the EPA it's not a congress passing laws. It is looking at the laws that Congress passed that tell EPA they need to act. And so it's a long process. And an engaged process with communities, with the affected parties, with businesses, with industries, you know, you have to touch base with everybody, and it usually it's science, science, science based. Then you look at how do I minimize the cost? Because the more you can minimize the cost, the more demand you can make in terms of reducing pollution 'cause it makes sense. That's what our, our job was and, and when they announced these 31 fundamental rules on how EPA does its work to protect air quality, to protect our drinking water supplies, to stop the indiscriminate cutting down of our resources and our trees for no reason whatsoever other than monetary value. In this case, I think it's just all about throwing those under the rug, pretending they didn't exist and not implementing them right away. That's the danger that is running in my head, which means we will be unprotected from pollution that could emanate and match that with how much they're trying to do to reduce monitoring and opportunities for seeing what kind of pollution is being admitted and actually going after that when they're exceeding those emissions levels. When you take all that into consideration, we could go back to square zero. I could go back to pretty looking rivers and a terrible Boston Harbor and I ain't going back there.

Kousha Navidar: Let's get more granular with it. Are there specific cuts that the public may not realize are important functions that the EPA serves?

Gina McCarthy: Yeah, well one of them is to make sure that we follow science. One of the cuts they're looking at is to eliminate our office of Research and Development, which if you look at that, that's our scientists. He has already taken out, and dismissed all of the advisory boards that we've had that actually oversee the work that EPA does on regulations to evaluate if we're doing a good job, how are we doing it and, and what should we do next? All those things are now gone. We have our environmental justice office. Now the only reason we don't have it now is because apparently they don't like environment or justice. Right. So we have human beings there that, that are solely looking at communities that have been left behind, communities that have been inundated by pollution, communities that haven't been invested in for decades and decades. And we all know that that's an equity issue. It's a racial issue in many cases, and they've just simply eliminated it. They don't want it. Plus they're moving forward to try to take all the money that was allocated directly to those communities, which amounts to a lot of money. Those resources are now trying to be squeezed back into the hands of Administrator Zeldin when legally those have already been allocated to those communities and they're sitting right now on all that money, unable to do anything because of this administration.

Kousha Navidar: I wanna play you a little tape of, uh, of, of Zeldin when he ended his announcement of the 31 actions.

Lee Zeldin: Today, the green new scam ends as the EPA does. Its part to usher in the golden age of American success. Our actions will lower the cost of living by making it more affordable to purchase a car, get your home, and operate a business. Jobs will be created, especially in the US auto industry, and our nation will become stronger for it.

Kousha Navidar: So our nation will become stronger for it. What goes through your mind and heart when you hear that?

Gina McCarthy: Well, everything that they cited was about advancing the economy, which none of us would ever be against, right? But, but what it's trying to do is, is basically give unfettered, uh, ability for businesses to pollute. There is no other way to frame that because EPA isn't an agency whose purpose or mission is to advance the economy. Now, don't get me wrong, I'm not saying EPA shouldn't consider cost because in most instances we are required to consider cost and you have to push back. But no one said EPA’s job was supposed to be to make sure our car manufacturers could advance their bottom lines. It was all about how do we make sure that our cars are safe for human beings in our natural environment? That's the difference. That is not our purview. We are not an energy agency. We are an agency who's solely working for the public, not for commercial interests.

Ariana Brocious Coming up, more from former EPA administrator Gina McCarthy on the dangers posed by the Trump administration’s rollback of dozens of environmental regulations:

Gina McCarthy: We will be unprotected. And match that with how much they're trying to do to reduce monitoring and opportunities for seeing what kind of pollution is being emitted and actually going after that when they're exceeding those emissions levels. When you take all that into consideration, we could go back to square zero.

Ariana Brocious: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Kousha Navidar: Help others find our show by leaving us a review or rating. Thanks for your support!

This is Climate One. I’m Kousha Navidar. Let’s get back to my conversation with former EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy. She was instrumental in helping create the Inflation Reduction Act, President Biden’s signature piece of climate legislation, which became law in 2022. What’s the future of this law, now that the Trump administration wants to eliminate many of its provisions?

Gina McCarthy: The good news is that most of the money has been given out, uh, the resources and the Inflation Reduction Act. So the real question is, are you gonna start cutting back on the tax credits and other ways that we could continue to keep the ball rolling? If you're looking at this from a political perspective, big P, you are hoping the Democrats will be, I think, very comfortable with continuing to move forward on the Inflation Reduction Act and see that it's fully implemented. it's the Republicans on the hill that you worry about, and what we know now is that there's letters from Republican representatives and, and senators saying, don't mess up the Inflation Reduction Act. And the reason for that is because 80% of the resources went to their communities and districts. So,my mother always told me not to cut off my nose to spite my face.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah,

Gina McCarthy: That, that's this.

Kousha Navidar: That’s one of my favorite phrases, by the way. I have to tell myself that all the time.

Gina McCarthy: But it, but it is a, it is, uh, an absolute apt phrase for this. It means why? Why do you want to slit your own throat? You know, let's use the money that we have available and let's use it wisely. And all of the strategies to actually advance credits and other mechanisms have been really good for this country, and Republicans and Democrats know it. So if they wanna take credit for doing more, that's great. If they wanna decide that they don't want it anymore, um, because you got plenty of billionaires who might think that that's the best outcome for them, right? If that's how they figure it, uh, I, I think they'll be hell to pay in communities across the United States.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah. One thing that you pointed out that I, I would like help kind of understanding is you mentioned closing the environmental justice office, right? What impact does that have to frontline communities?

Gina McCarthy: Well, it certainly tells them that this president has no interest in them. That he's not working for them. And it's pretty clear, I think, to the vast majority of us that we know who his friends are and we know what direction he's trying to take. And it's certainly not to benefit the communities left behind. Look, the reason why you have an environmental justice office, and the reason why I keep scratching my head about why DEI has become mm-hmm. And, you know, such a pressure point. It, it, it's, it's simply, uh, we, I think we really have to admit that it's communities that have high numbers of minorities. It's communities that have been disadvantaged on purpose over decades. You know, it's communities that need a government to stand up for them. It's communities in the highest levels of air pollution that need to have an ability to know that they can reduce their emissions if we work together. You know, you talk about wanting how great EVs are, well, not in those communities. 'cause they don't exist there. You can't afford them in those communities. And so it's all about how do we begin to, you know, reinvest in housing and lower energy costs by using heat pumps and solar and wind. How can we work together to raise the level of hope and opportunity in those communities and deliver on that hope and opportunity.

Kousha Navidar: Hope and opportunity. Also, I would say like awareness and motivation. Maybe like mobilization of individuals.

Gina McCarthy: That’s right. And I think you're going to see some of that. You know, I think you're gonna see that across our country because it doesn't feel right anymore. Our country doesn't feel like it's the democracy that we've all, you know, been, been ready to, to engage in, and willing to fight for.

Kousha Navidar: Can you point to something specific about that? What are you seeing that kind of suggests that it's gaining traction?

Gina McCarthy: Protests are out there, okay. People are starting to speak up. I'm doing a college tour. I'm going tomorrow to Wake Forest in North Carolina. Man, were they hard hit, with disasters and new disasters are popping up in that state and, and I'm attending a resilience,and adaptation conference the day I come back to talk about what's Massachusetts doing, because we have a lot of work to be done to protect ourselves. So there's a lot going on and I feel like , you know, like always young people tend to be our saviors, but in this instance I see women kicking a**. I'm sorry if that's a blunt thing to say. They're going everywhere. You know, it's, it's, uh, so people I think, beginning to stand up and take notice, uh, I just hope that it's the same in communities that really have been afraid to stick their head up too high. What I'm doing now is, is really working at Bloomberg Philanthropies, at America is all in. And the reason for that is that when the federal government decides to fall apart, which it seems to be doing, you do have to rely on governors and you have to rely on city and town leaders. And that's the quiet murmur that is really building now we are giving support to those communities so they know that they can stand up for themselves and they can speak up.

Kousha Navidar: You have so much experience going to conferences like these, I mean, during a presidential administration as the head of one of the most visible agencies. A lot of your job is traveling and talking to folks and going, you know, you're doing a college tour now. I'm sure your term was a lot of tours around the country. Is the vibe different now than it was, say, two administrations, three administrations ago? When you're going and talking to Wake Forest, for instance.

Gina McCarthy: It's, it's actually more exciting, uh, because before I, I think, you know, EPA was doing pretty well when I was there and President Biden did a good job in the White House, and we did it because we personalized the issues. We made it mean something and have people understand it. That's what we have to do now, and that's what I'm doing, is I'm going to let them know, you know, that their lives are at stake. Their kids' future is at stake. It's not about greenhouse gas emissions, it's about clean energy that's gonna save us.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah. It's about what color the river is.

Gina McCarthy: Exactly. You know, it, it, this, this is just so important that we don't get captured in just being arguing Republicans and Democrats. It's not about that. To some extent, yes, would I like to have Congress stand up and really do something to protect people again. Sure, but I'm not gonna sit around and wait for them to get some epiphany. You know? And, and, and young people get it. This is their lives. They know the value of clean energy. You know, environmental justice communities should have access to that clean energy first before anyone else, why wouldn't you? They understand the price of housing and how if I can save a couple of hundred bucks on clean energy living in that house, I'm gonna do that.You know? So the opportunities in the options are out there and that's why it feels different. You know, it feels like young people are gonna once again step up in a way that usually young people have to. But, but hopefully it would be done in a way that celebrates, you know, what we can do, whether than dwelling on what we can't. America is all in, captures like, like, uh, two thirds of the US population and three quarters of the GDP alone by the people we reach. So don't be surprised when you see them standing up because we're trying to do our best to give them the support they need. And I hope people, you know, from the conversation can take away if nothing else, that message, you know, we may not have the leadership we want, but we have leaders. And we are gonna keep nurturing them.

Kousha Navidar: We really appreciate. I mean, I appreciate getting to hear from your perspective as somebody who's really rolled up their sleeves and has seen the trajectory and especially sees the places of, of progress and opportunity to watch out for all of these different communities across the country and the climate itself. So, I expected this conversation to be thrilling. I am so lucky and happy that we got to talk together. Gina McCarthy is the former EPA administrator under Obama and the first White House National Climate Advisor. Gina, thank you so much for hanging out with us.

Gina McCarthy: It was great. Thank you. Appreciate it. Keep going.

[music cue]

Ariana Brocious: Among the many federal agencies experiencing staffing cuts under the Trump administration is the U.S. Forest Service. It's responsible for everything from maintaining hiking trails to fighting wildfires and making public lands less prone to burn in the first place. As the climate crisis continues to exacerbate the size and scope of wildfires, some of those workers are now warning that staffing cuts make the agency less prepared for the upcoming fire season. From Oregon Public Broadcasting, April Ehrlich reports.

April Erlich: As a Forest Service ecologist in Oregon, Lanny Flaherty's day-to-day job involved collecting data, a lot of it related to plants. Some of Flaherty's data goes into wildfire behavior modeling. For example, understanding where brush and trees grow on a landscape gives firefighters a better understanding of how a fire might move through it.

Lanny Flaherty: When you bring in 5,000 firefighters from all over the country, you need local specialization there to tell them where the stuff is.

April Erlich: Flaherty was one of 2,000 probationary workers in the Forest Service who were recently fired. That number was confirmed by a spokesperson with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which oversees the Forest Service. In interviews, almost a dozen current and former Forest Service employees say they're worried about the way these cuts will affect fire season. Flaherty says it's not just his data collection that's affected. He also helps fight fires when the Forest Service is understaffed.

Lanny Flaherty: Every role is so dynamic. There's a huge amount of those secondary roles that aren't just directly digging line or swinging a tool that support the firefighting operations.

April Erlich: Field rangers tasked with patrolling the vast wildlands that make up the West were also among the people fired, including Liz Crandall. She's based in central Oregon.

Liz Crandall: I'm eyes on the woods. I'm the person that's seeing every corner of the woods that others might not see.

April Erlich: Destroying abandoned campfires before they turned dangerous was part of Crandall's job. And, like Flaherty, she assisted firefighters when needed. Crandall says she has responded to a dozen major wildfires.

Liz Crandall: I'm a Firefighter Type 2. I went to guard school. I have my chainsaw certification. I'm able to go on a fire line.

April Erlich: Crandall and Flaherty both worked for the Forest Service for years, but they entered into probationary periods when they took on new roles. In a statement, a spokesperson with the USDA said the agency did not fire any operational firefighters and is, quote, "committed to preserving essential safety positions." They did not respond to questions about employees who were certified to fight fires as secondary roles or people who helped do fire prevention work.

Aaron Weiss: You can come up with a lot of ways in which this goes sideways very quickly for mountain communities, for forest communities.

April Erlich: Aaron Weiss is with the conservation advocacy group Center for Western Priorities. He says he's concerned that these firings will hinder wildfire prevention work like prescribed burning.

Aaron Weiss: This is the single best tactic that we have across the West to minimizing wildfire risk when it comes to wildfire season.

April Erlich: And this is all happening on top of a hiring freeze on seasonal workers at the Forest Service that the Biden administration announced last year. I'm April Ehrlich in Portland.

Ariana Brocious: Thanks to Oregon Public Broadcasting for sharing that story with us.

Kousha Navidar: Coming up, a critical federal agency you may have never heard of is also seeing its staff slashed under Trump:

Umair Irfan: NOAA is housed in the US Department of Commerce, and so a big part of its mission is looking out for industries that are directly affected by things like weather, by climate, by changes in the atmosphere. So that includes fisheries, shipping, air travel, farming.

Kousha Navidar: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Ariana Brocious: This is Climate One. I’m Ariana Brocious. You might not have heard of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, also known as NOAA. But every weather app you use and every TV forecast you see is based, in part, on data from NOAA. In addition to helping predict the weather and plan for risks and severe events, it’s also a vital organization that helps us understand the effects of the climate crisis. And right now, the agency is in the crosshairs of the Trump administration.

[music change]

I talked with Vox climate and environment reporter Umair Irfan about how important NOAA’s work is and what’s been happening at the agency.

Umair Irfan: NOAA is a research agency, but critically they're focused on applied science. They're looking at things that directly affect people's lives, and particularly that affect the US economy. NOAA is housed in the US Department of Commerce, and so a big part of its mission is looking out for industries that are directly affected by things like weather, by climate, by changes in the atmosphere and our understanding of the oceans as well. So that includes fisheries, shipping, air travel, farming. So a lot of critical industries in the US depend on the foundational research done at NOAA.

Ariana Brocious: As a reporter, you've talked to scientists at NOAA a lot for background on stories, and now you're covering what's happening to the agency as it's being targeted by the Trump administration. So what's that experience been like? What have you been finding?

Umair Irfan: Well, it's interesting because, um, I've talked to scientists pretty openly in the past and, you know, have had a pretty free flowing exchange about ideas and stories and, and fact checking and verifying, things like that. But more recently, uh, some of the folks that I've been used to talking to have become a lot more disciplined or maybe a lot more formal in terms of how they interact with me and, and insistent on going through the press process or deferring to other people and, and giving me more canned responses rather than the more direct responses that, that I've been getting sometimes in the past. And so there does seem to be somewhat of a chilling effect, at, at the agency. And some of the folks that I've talked to off the record have said as much that they know that their communications are being monitored. And of course they don't wanna run afoul of their leadership at the department or at the White House either. And so they're being a little bit careful. And then more broadly, across the government, there is sort of this perhaps not censorship, but a way of reframing some of the issues that are in the crosshairs of the Trump administration, particularly around climate change. deemphasizing that as a focus and focusing more on things like changes in weather patterns, or reframing those discussions as measures of extreme risk, rather than talking directly about how humanity is warming the planet.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, it's interesting that these things are basically the same, but they're going by another name and that's kind of maybe a safer way in this moment to talk about some of these critical issues. So, obviously the Trump administration has been targeting many aspects of government, to reduce the size of government in this quest to make it more efficient. NOAA has been one of the agencies targeted for layoffs. How many people have been laid off so far or maybe just sort of a rough percentage of their workforce?

Umair Irfan: Well, NOAA has about 12,000 staffers around the world, about half of them are actually engineers and scientists. And of those so far, at least 880 have been laid off because they were probationary employees, and so they were technically easier to let go under the government's hiring system. But NOAA has also announced that they're seeking another 1000 layoffs on top of that. And so they're trying to see how many people are going to be retiring or through ordinary attrition, and then from there work towards cutting the head count until they get to that number. So we're looking at roughly 1800 to 2000 people already being announced. But if you look at some of the things that the Trump administration has said, and particularly some of the advisors that he has had, I'm thinking specifically about some of the folks that wrote Project 2025, the Conservative Heritage Foundation's Playbook for revamping government. They call for agencies like NOAA to roughly lose about half of their head count and have a lot of their functions being privatized, and so that's something that may potentially be on the horizon as well.

Ariana Brocious: I wanna get more into that and sort of the plans outlined in Project 2025, but, but just quickly, for people who maybe don't entirely understand the way the federal hiring system and employment system works, can we just break down what this probationary period means? how it might differ from things in the private sector?

Umair Irfan: So the probationary system is written into the law. Basically, if you are going to be a federal government employee at an agency, you have to not just go through the job interview process to be hired. You also have to be evaluated in how you actually do the job. That's because a lot of government jobs have very highly specialized obligations. There's a lot of specialized training that goes into it, sometimes lasting weeks and months. There are certain things you can only do certain times of year, like if you're interacting with Congress. You know, Congress is only in session during certain times. Certain types of budgets and appropriations only happen at certain times of year, and so you have to kind of wait to actually see how someone does the job. And on top of that, you know, these are people again, being brought into the government, but also people who are being moved within government. So if you transfer from one role to another, and, uh, one scientist I talked to, he was on probation because he was promoted. He actually done such a good job, he was moved to a different role, a management role, and had to be put back on probationary status. It was a recognition of them actually doing good work. So this is not like the legal sense of probation. It's not somebody who's being punished for a crime, but rather this is somebody who is being sort of evaluated on the job for how they're doing it. And while probationary employees technically are easier to let go, there are still requirements written into the law for what reasons are allowed. And that's specifically failure to perform the duties that they've been assigned or failure to meet the mandate of the department that they're, they're within. And so you can't simply just let people go after they've been hired and are on probation. There is a legal requirement that you meet another standard on top of that, and that's part of why there are some lawsuits now suing to try to get probationary employees back on the job.

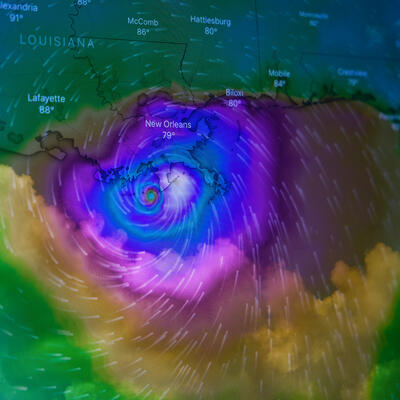

Ariana Brocious: Right, one of the things you mentioned when we spoke before was within NOAA there are some very specialized jobs, probably that's true at, at all federal agencies. But one that I, I thought was so striking that you mentioned was people who fly into hurricanes to measure intensity, gather data, be able to predict what the impacts might be. And so obviously that's something that takes a lot of training, right.

Umair Irfan: It does. And I talked to a scientist who was laid off, who was one of the, uh, passengers on these hurricane hunter aircraft, and his job was to do exactly what you described to study hurricanes as they happen in the real world. Now, hurricane season only lasts a few months and there's only a handful of major hurricanes per year. And so if you want to evaluate how well a hurricane hunter scientist actually does the job, you kind of have to wait around for a storm to happen and then actually see what they do with the data that they gather and analyze. And so that's one of the performance metrics that they're evaluated on, and that's kind of why it takes so long. But also, this is somebody who has a long history of working with government, even from outside of government. So this, uh, the scientist that I talked to, he was, uh, formerly working at a university as a collaborator with NOAA, and then was hired on by the agency itself. So, this is not somebody who was completely unfamiliar with the infrastructure of how government work is done. And, he said he viewed being hired at NOAA as a kind of a promotion and saw that he was on this probationary status as just an extension of the hiring process, that this was basically just kind of part of the benchmarks that he had to meet. But yeah, it's a very highly specialized skillset. There's only a handful of people in the world that will do this. Almost nobody in the private sector. These are either gonna be scientists that work at universities or scientists that work at the government, who has a plane that they're willing to fly into a hurricane. It's NOAA. They've got two of them.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, I don't know. I don't think there's an amount you could pay me to do that. A lot of the people that have been laid off were told that they quote no longer meet the current administration's needs. I'd like to kind of circle back to what was outlined in Project 2025 and what we've seen happen across the government in the last couple months where there's been a lot of scrutiny on things like DEI, climate science, sort of in general. What do you think that rationale being given is indicating about what the administration wants?

Umair Irfan: Well, broadly, I think there's just this, uh, across the board push to cut the size of government, and that's the targeting of the probationary employees. About one in 10 federal employees are on probation at any given time, and so that's basically a 10% cut across the board, but there is. sort of an ideological push specifically against NOAA because it is also one of the agencies that does a lot of the government's work on climate change. That its job is to provide the factual basis for government policies relating to greenhouse gases, how we reduce them, how we adapt to the consequences and thereof. And for folks who are disinclined to believe in climate change or, or think that it's not something to worry about, they view this as alarmism and, the conservative think tank apparatus, like groups like the Heritage Foundation have called this agency like, you know, a front for, climate alarmism. And that references to climate change should be eradicated, um, and that these functions should be dismantled and what's left should be privatized. So there's this sort of broader ideological push specifically at some of the functions that NOAA does with respect to climate change that are specifically being targeted here.

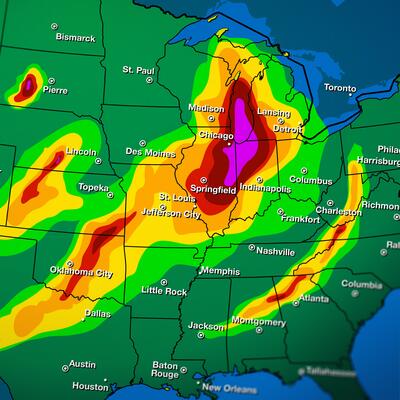

Ariana Brocious: And what effect do you think these cuts will have on the agency's ability to do that work?

Umair Irfan: Like a lot of government institutions, you know, you can fire a lot of people and the bus will keep rolling, it will take some time for the wheels to come off. And so there is a little bit of momentum kind of baked in with some of the systems. But with NOAA, we are already seeing some of the effects of this. You know, for instance, every day the United States, across the country, we launch weather balloons in order to inform our weather models, so we have these sophisticated computer simulations of how the atmosphere and the earth interact. But in order to actually get something useful out of them, we have to feed in the actual temperature, weather, and moisture conditions. And the best way we do that is by launching weather balloons every single day across multiple sites across the country. These balloon launch sites are staffed across the country by maybe one or two people. And if you lose that one person, then that office closes down and we've already seen some of these balloon launches stop. And what that means is that the weather models that they inform are not going to be as good. The resolution of the forecast will be decreased, the skill, the time at which you can look ahead and try to anticipate a thing like a major storm or any flooding event or things like that, those are going to degrade and we're already seeing the front end, the inputs being degraded, and I think over time we are gonna see the outputs, the forecasts we get out of these models starting to degrade as well.

Ariana Brocious: And that's really concerning. And I just wanna pause and recognize that because there are so many different people and companies and entities, as you said at the beginning, who rely on this data that comes out of NOAA. It's not a standalone agency. It is actually housed within the Department of Commerce.

Umair Irfan: Yeah, the roots of NOAA goes back to basically trying to provide the information necessary to build the US economy and. As the US economy has evolved, NOAA has evolved as well. Like it's also now providing things like sea floor mapping for things like offshore oil and gas drilling. They regulate the fisheries. and then of course weather forecasting, particularly extreme weather. Extreme weather is still dangerous and deadly. and to whatever extent that we can, anticipate them, that ends up, you know, helping save lives, but also is good for the economy. But increasingly, it does seem like an odd fit that the Department of Commerce, which also handles things like tariffs and trade, is the parent agency for NOAA. NOAA has a multi-billion dollar budget, and it's about 60% of the entire commerce department's budget. Think of that as like a financial agency. It's currently led by Howard Lutnick who led a financial services firm. It's really, if you look at its function, it's mainly a science agency and a lot of people think that that's misplaced. Now. Recently we just learned that Howard Lutnick wants to sign off on all of NOAA’s grants and projects that exceed a hundred thousand dollars. And so that's adding another layer of approvals that is causing more bureaucratic delays for NOAA's functions. And so some of the stuff that has already been approved and has been funded, they're having a hard time delivering on because there's this now, this other layer of bureaucracy that they have to go through and they have to go through a finance person, not a scientist, to evaluate whether or not this is worthwhile.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah, it just, seems so counterintuitive to me. And, you know, we're talking about weather prediction extreme storms, all this very valuable information. So why would pro-business Republicans have a problem with this agency, which, which we should say is not a regulatory agency. It basically exists to serve and provide information, right?

Umair Irfan: That's right. And, I think there has been a little bit of buyer's remorse. There have been some NOAA employees who were laid off or fired and then hired back. And so that we've already seen them finding out the hard way, just how important some of their functions are. But, again, going back to ideology, a lot of the functions that they're hoping that NOAA does could be privatized. So there's now been a growth in the private sector in terms of weather forecasting, there are a number of companies that provide weather forecasting services for hire, And there's this idea that perhaps you could privatize a lot of NOAA's functions that rather than offering a lot of this weather data for free, you could offer it as a product and, and make people pay for it or go through some of these private sector gatekeepers. But even some of these, private weather companies that provide these services that sometimes duplicate NOAA's functions. Many of them say that they actually rely on no as well because again, NOAA is a public agency. Their public information also helps inform private companies as well. And so they rely on having that information being widely available. And so the thinking is that if that information is valuable, then perhaps it should be given to the private sector and not the government.

Ariana Brocious: And so just to explore this one degree further, what would be lost by the American public if an agency like NOAA's services were to become privatized? Because I know that government subsidizes a lot of this research, but it's also for our collective benefit.

Umair Irfan: Yeah, that's right. You know, I think there have been some estimates about how NOAA delivers, I think somewhere close, anywhere between five to $10 of economic benefit for every dollar that's invested in it. And so it's one of the better bargains in government as far as the things that it delivers to our economy, but without that, then yeah, we lose that bargain. Now, it's not simply, you know, or not knowing whether or not you're gonna need an umbrella or having to pay for an app, rather than being able to go to a public forecast. you know, over time some of the more sophisticated tools that NOAA has are gonna go up behind a paywall or not be as publicly accessible. And, and that in turn will raise operating costs across the economy. Because NOAA does publish a lot of public information. And there's like this whole community of forecasters who are you know, amateurs that also help serve like their local communities as well relying on NOAA's data. There's a bunch of hobbyists that rely on NOAA's space weather forecast. NOAA is one of the agencies that forecasts auroras. And so like, there's a lot of like –

Ariana Brocious: Those beautiful light shows in the sky.

Umair Irfan: Exactly. And part of the NOAA's job is to look at the sun and see how often it's sending out flares towards earth that cause these geomagnetic storms, which also can disrupt satellite communications and ground-based communications as well. So they're not just looking at storms on earth, they're looking at storms in space. And I think you also lose, I guess, a sense of wonder because these are things that the public can directly engage with. Like you can go to NOAA's forecast, you can go to the National Weather Service and have a reliable, nonpartisan public source of information on things like where the latest hurricane forecasts are, where the trajectories are, that, uh, that is considered for the most part, very reliable and very trustworthy. If you lose that source of trust, if you lose that source of public information, it makes it much harder for people to get valuable information in those circumstances when you have a hurricane barreling towards the coast, when you see a major storm coming, when you are anticipating wildfires. and so the net risk could potentially go up.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah. Yeah. So if a new administration is more sympathetic to the realities of the climate crisis. How quickly do you think we could reassemble the key functions of NOAA, of this agency?

Umair Irfan: Many of them could be reassembled fairly quickly. The expertise doesn't necessarily go away. The scientists are still there, and many of them do want to work at NOAA. and would be eager to come back to have their jobs and, and can pick up where they left off. But there is lost time. Over the course of years, NOAA has managed to, for instance, improve its hurricane forecast. They can now anticipate hurricane pathways and trajectories 72 hours in advance with the same resolution that they could only have a day in advance 30 years ago. So now you have 72 hours of warning for where a hurricane's gonna land compared to just a day of warning. That's a lot more time for people to get outta the way. That saves lives. And every hurricane that they go out into and explore and send this aircraft into, they get better data. And they use that to develop the next generation of models. So year after year, season after season, these tools keep getting better. And as we stall that progress, we lose some of that forward momentum. At the same time, seeing all this turmoil can discourage new people from entering the agency. There's a lot of weather nerds out there that dream of working at NOAA. And when they realize that their skills and their passions are not being valued, we may not be as inclined to go work for the government and in public service. And so there, there is a pipeline problem there as well. And this is kind of true across the government that a lot of federal agencies are gonna see retirements over the course of the year. And you need a fresh crop of people constantly coming in to keep the ball rolling. And without that, those other institutional functions will stall as well. and the harm from that can be harder to repair. Like there are, again, a handful of people who do this research in the whole world. And if you have like the one person who knows how to operate the radar and knows all the quirks of the software and knows how to integrate it and actually, uh, plug everything together and they quit and they, they're not replaced, then a lot of people are gonna be left scrambling and, and overall quality of the work that they do will degrade.

Ariana Brocious: You've talked with different employees at NOAA who have been let go, or are in this kind of unknown period and. I just am curious what you've been hearing from them, because it sounds like there's a lot of, kind of sense of respect for working at this agency, sense of kind of duty and, and pride and so I'm wondering how, how they've been handling these changes.

Umair Irfan: I think a lot of people do end up taking it kind of personally. People work in government, in these kinds of agencies have a sense of duty. Like I've talked to a lot of folks who were former military who served in other capacities across government and who probably could get a much more lucrative job in the private sector but still insist on working for NOAA because they have a personal history with extreme weather, because they've seen their communities ravaged by major storms and, and have dedicated their lives to try to prevent them. And so this is stuff where people like actually have sort of a personal commitment to, and, and losing that and seeing that, you know, being denigrated publicly really does kind of hurt. But at the same time that passion doesn't go away. And that does mean that if they do get the opportunity to come back and to resume their work, many of them are eager to do so.

Ariana Brocious: Yeah. Well, okay. We'll have to keep an eye on what's happening. There's a lot in flux right now. Umair Irfan is a reporter at Vox. Thank you so much for joining us and talking with us today on Climate One.

Umair Irfan: I appreciate it. Thank you for having me.

Ariana Brocious: And that’s our show. Thanks for listening. Talking about climate can be hard, and exciting and interesting — and it’s critical to address the transitions we need to make in all parts of society. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. You can do it right now on your device. Or consider joining us on Patreon and supporting the show that way.

Kousha Navidar: Climate One is a production of the Commonwealth Club. Our team includes Greg Dalton, Brad Marshland, Jenny Park, Ariana Brocious, Austin Colón, Megan Biscieglia, Kevin Lemons, and Ben Testani. Our theme music is by George Young. I’m Kousha Navidar.