EPA Then and Now

Guests

Lynda Deschambault

Ben Franta

Gina McCarthy

Summary

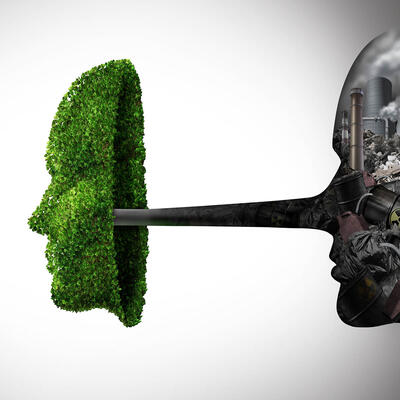

It was in 1970, under President Nixon, that the Environmental Protection Agency was founded. While the Agency enjoyed tremendous bipartisan support for decades, the last nine years have seen a decline in support from congressional Republicans. Recently, former EPA Administrator, Gina McCarthy, explained that she is not worried about protections being rolled back—she thinks they will withstand the assault—but rather about the budget cuts.

Portions of this program were recorded at the Commonwealth Club of California in San Francisco.

Full Transcript

Announcer: This is Climate One, changing the conversation about energy, economy and the environment.

Oil companies have known about the dangers of burning fossil fuels for longer than you may think.

Ben Franta: I found this transcript, Edward Teller telling the heads of the oil industry in 1959 that CO2 emissions could submerge New York City.

Announcer: Since 1970, the EPA has been protecting our health and safety by enforcing regulations on the industry. But under the Trump administration, things have changed.

Lynda Deschambault: Suddenly the people we were regulating were now the regulators.

Announcer: And the agency no longer seems committed to its founding mission.

Gina McCarthy: They don't have a right to misinterpret the law. They don't have a right to take science facts off the webpage as if issues like climate change didn't exist.

Announcer: The EPA Then and Now. Up next on Climate One.

Announcer: Welcome to Climate One – changing the conversation about America’s energy, economy and environment. I’m Devon Strolovitch. Climate One conversations – with oil companies and environmentalists, Republicans and Democrats – are recorded at the Commonwealth Club of California, and hosted by Greg Dalton.

Founded in 1970 under President Nixon, the Environmental Protection Agency was created to protect Americans’ health and environment by writing and enforcing regulations based on laws passed by Congress. While the Agency enjoyed bipartisan support for decades, the last 9 years have seen a decline in support from congressional Republicans. And the Trump administration has been largely hostile to its mission. EPA administrator Scott Pruitt sued the agency more than a dozen times when he was Oklahoma Attorney General. Pruitt’s EPA has downplayed science and scrubbed mentions of climate change from its website.

Gina McCarthy served as EPA Administrator under President Obama from 2013–2017. Following her tenure, she took a position at the Harvard Chan School of Public Health. Greg Dalton spoke to her about climate change and today’s EPA.

Greg Dalton: What’s the biggest impact of the Trump administration? What's the biggest damage they've done in terms of environmental protections?

Gina McCarthy: Well, you know, it's not over yet. But what I'm most worried about is not, and not really the rollbacks that they’ve announced repealing the clean power plan and other initiatives disappointing. But I just don't think that they’re going to be successful. I think we know very well that we followed the science and the law and we developed the facts and we did the administrative process. And I also know, factually, they’re not engaging the core staff what’s so important to doing those well. And so I'm pretty confident that we did it right and that any attempt to undo it is going to be unsuccessful and lengthy in the courts. I guess what I most worry about is the attack on science and the budget challenges that they’re putting EPA under. Those are systemic things that go well beyond this year and well beyond the ability for the agency to easily bounce back. You know their budget cuts are really not just targeting EPA in terms of potentially cutting it by a third, but they’re targeting the science. They’re targeting our scientists and EPA is a science agency that’s what we do for a living, you know, and I think that's a serious threat that I think we see goes well beyond EPA in this administration. They simply don't want science that they have to deal with.

Greg Dalton: And some of the scientific advisory bodies have been disbanded or the composition has changed. What kind of lasting impact does that have if the advisory body goes away, can you put it back together in a few years?

Gina McCarthy: I think you can but, you know, you sent some terrible signals to the young scientists in the agency about whether or not they had like to come into public service at a much lower salary or should they go into the private sector. What would you do if this is sort of the foundation that they’re creating when you want to go into public service? They are, you know, profoundly changing the way that these types of changes in administration normally handled and looked at. You have a right to different policies. You do. I mean, that is, you win an election you get to do things the way that you think is best. But they don't have a right to misinterpret the law. They don't have a right to take science facts off the webpage as if issues like climate change didn't exist. They don't have a right to shortcut the administrative process and you don't have a right as an administrator to go into an agency and not embrace the mission of that agency. And clearly at EPA we do not have an administrator that doesn't really fully embrace the actual mission of the agency to protect public health and the environment.

Greg Dalton: I've read that up to half of EPA employees are eligible for retirement in the next five years. So what is that prospect does that mean, we’ve seen that within other areas, NASA, air traffic controllers there’s a big demographic boom that retires at a certain time. But what could that do to the agency, people gonna just give up and walk away.

Gina McCarthy: Well, you know, in honesty I think the administration is really trying to set the stage to make it difficult for the employees to continue at a high level with the work that they’re very good at and have a history of being successful in which is to continue to progress and the mission of the agency. And so as they've made it very challenging --

Greg Dalton: So it’s half the EPA retirees they’re okay with that.

Gina McCarthy: Well I actually think if you look at recent web pages one of the goals of this administrator is actually to lower the number of staff in the agency. There’s nothing there that says I'd like to protect public health better and save lives and make people less sick from air pollution and other challenges that we know. Every administrator before that, including the Republican administrators is all very concerned is not really the central tenet that is guiding the decision-making. So we know we’re losing staff up a level Korea staff who have a history there, I can remember in particular, one of them left and all she really said was I realized I had become irrelevant. That was the saddest sort of remark that I had heard. It wasn't out of bitterness. It was out of really serious disappointment that the history of knowledge that our scientists have accrued. Their ability to understand the law, understand its history understand its policy implications. Their ability to adapt to changes in the world and continue to make progress moving forward, all those abilities are at risk from being lost in terms of the decision-making of what is one of the most successful public health agencies that's ever been created. And that to me is not just disappointing but it should be frightening to people frankly. It should make them sit up and take notice. Not the changes right away will result but over the long haul. Just think about the success of EPA. Think about what the pollution looked like in the 60s and is that really the back to basics agenda that any of us want to support? You know, I've worked for six governors five of them were Republicans, including Mitt Romney. I never went backwards. They never asked me to go backwards. They always had their eye on clean air and clean water and clean land. And climate change is no different, except that it threatens the ability to maintain all of those things. It threatens the future of our kids. Let's get real here and embrace the science and develop the technologies and invest in the innovations that we need to continue to make progress moving forward. That's what EPA would do under a leader that embraced its mission.

Greg Dalton: Mitt Romney said to be considering a Senate run from Utah, a coal state. Knowing what you know, having worked for him when he was governor of Massachusetts. What kind of senator would Mitt Romney be on EPA and climate?

Gina McCarthy: Well one thing about Governor Romney is I would say is I enjoyed working for him. I work for him for I don’t know may be a couple of years. I had a great opportunity to move to Connecticut. I can't tell you that I agreed with every decision he made from that point on. He certainly moves forward with a climate action plan that I helped design and it was a pretty solid aggressive plan. But even then he caveat it his cover letter to that plan by saying it's a no regrets policy these are all good. Because they were, they were all opportunities to save costs through energy efficiency and other things. And he caveat it by saying, but I'm not sure about the science. And I think we saw him, you know, change some opinions over time, which is not unlike any politician. But, you know, like many Republicans I don't think that they want to breathe dirty air. I don't think they want to drink contaminated water any more than their constituents do. And the funny thing is that while the Republicans seem to have as a platform gets rid of EPA goal, I got lots of calls from Republicans when their local constituents were threatened. And I think we’ll continue to see that. So while this challenges we will weather those challenges, you know, we this is hopefully, you know, a limited time when people have forgotten the importance of that mission and how important it is to move it forward. But I'm not going to get disappointed and I am far from being hopeless. I'm sorry. Many people think I'm hopeless but I’m hopeful.

Greg Dalton: Offshore oil drilling in the news a lot and Californians are opposed to it and a lot of states are opposed to it. But when we say we don't want to drill off this coast or that coast, isn’t that really just nimbyism saying well go drill in Venezuela or Nigeria where the environmental regulations are not as strong as they are in the United States. So isn’t it some sense better to drill here because it will happen more responsibly and cleaner?

Gina McCarthy: Well that’s hard for me to believe at this stage. But, you know, frankly we all know that there are challenges with drilling in the ocean. I only need to say two letters, B and P for you to think about that. And really this brings up one of the most fascinating things is that this administration at the same time as they were proposing to cut down some of our beautiful protected natural lands, they announced that they were not going to be moving forward or they were going to be repealing the protections that the bipartisan committee that looked at the Deepwater Horizon disaster had said to put in place that provided some technical measures that would eliminate some of the causes of the BP oil spill. And they decided they were not going to move those forward. I mean there were things like make sure you have all of these protections technically but an independent person comes in to look at whether or not you're safely operating. Things that any business would do that had an opportunity for the disaster that we saw before. So it's not just a given that these things are done well and safely and frankly for an administration that says they want to take away authorities of the federal government and shift it toward states to suggest that they should unilaterally across this country say that it's open season for oil drilling off of our coasts is contrary to states rights. If that's really what your goal is.

Greg Dalton: So you think it’s better to drill if we have to drill get in from the United States better to do it on land than offshore?

Gina McCarthy: Well there are two things I think. One is I'm not sure we have to drill. Right now we are essentially moving forward in the most cost-effective way we can to deliver clean energy to people. And clean energy happens in the marketplace to be the most successful and cost-effective strategy. So if you really want to get real about giving people what they want, which is low-energy costs and protecting people from hazards associated with climate change, and from disasters like the BP oil spill, then start thinking about how you move renewables into the system more cost-effectively. And that's probably the better strategy than drill baby drill. That has not worked and it won't work and it really doesn't recognize our absolute responsibility to move towards a low carbon future.

Greg Dalton: And the marketplace is doing that some of the cheapest power ever is now happening solar power, et cetera. It's beating coal, it’s beating natural gas, beating nuclear the market is --

Gina McCarthy: If government at this point just stays out of it. We are absolutely moving towards a low carbon future. And the interesting thing is that as this federal government has divested itself and thinking about climate moving forward to protect our public health and the environment you see cities moving forward to do this. You see, you know, businesses moving forward to do this. You see states well beyond California who still remains in a significant leadership position. This stepping it up and you know frankly it doesn't surprise me because in the environmental world we didn't get federal action on climate change until the Obama administration. And think how long the states were in the game. So it's grassroots organizing that matters. So when people start worrying about what's going on in the federal level. I tell them, you know, it worries me as well, but I'm not gonna get discouraged because I know where the real action is. And if cities and states and the business community continues to embrace this challenge, all the federal government needs to do is step aside, which is exactly what they're doing.

Announcer: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation with former EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy. Coming up, we’ll hear more of that conversation, and Greg Dalton will talk to a recently-retired EPA staff scientist who describes some of the change happening inside the agency:

Lynda Deschambault: It was almost don't do your job and put on your cloaks of invisibility and back off.

Announcer: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Announcer: You’re listening to Climate One. Let’s get back to Greg Dalton’s conversation with former EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy.

Greg Dalton: Lot of companies are embracing sustainability it makes good sense for their bottom line, their employees want it, their customers want it. But the auto industry was one of the first after the 2016 election to say we want to reduce the fuel efficiency standards. That was one of the center piece accomplishments of the Obama administration on climate. How much at risk are we is there for reducing auto efficiency standards getting to 55 miles a gallon?

Gina McCarthy: Well I think the fact that we have a system that sets regulations at the federal level and then also provides an opportunity in California to set standards has been what has allowed us to move forward to get more fuel-efficient vehicles. It seems clear to me that our auto companies did not have the foresight to understand that consumers want fuel-efficient vehicles. And so they were on the verge of bankruptcy before they really were brought to the table to get more serious about looking at cars of the future instead of trying to continue to advertise the gas guzzlers of the past.

Greg Dalton: Yeah they’ve agreed to those increase standards after the taxpayers bailed them out.

Gina McCarthy: They were going bankrupt and frankly all that was being requested of them was to use currently available technology to sell cars that people in the United States of America might want to buy, which seems pretty fundamental to getting out of the bankruptcy. And they've done very well for themselves. And I realized that they went in and they asked for all of these standards to be re-looked at. But I think they’re gonna have to make the case as to why they can't achieve these standards with already known in pretty solid technology moving forward. You know before I left the administration I made a decision that we didn't need to relook at the standards. And they certainly want to challenge that but I did it because we had done a thorough look at the technology. And what that said to me when you look at it and that's the conclusion of our technical staff and our scientists was that the technology was available today and even less expensive for them to achieve the kind of reductions that were being asked of them. You know our automakers I think are beginning to recognize something and whether they admit it or not I don't know but then not setting the market for cars in the world anymore. You know, China is going to be setting that market and there are been clear signals from both the EU about their intent to ban the internal combustion engine in the Ford by 19th, I'm sorry by 2040. And also China is considering the same thing. And even visits from the CEO of General Motors didn't change their mind. And so if they want to step aside --

Greg Dalton: India too.

Gina McCarthy: India as well. You know they know that the world is changing. And what they really have to do is instead of looking at whether or not they can achieve the standards they need to look at the direction the world is heading and they need to maintain our place as a leader in that world.

Greg Dalton: There was about 90 million new cars hit the road last year. 2 million of those had a plug. So electric cars growing but still a tiny percentage of the market and so people still, there's lots of choices now, electric cars are on the market there’s 20 some models, but there's still a small percentage gas is still king.

Gina McCarthy: Yeah, there’s no question about it which I think is why the EU went to 2040. But the handwriting is on the wall and the infrastructure is being constructed even outside of California. You know that's probably the only good thing that came out of the Volkswagen fiasco was that that working together we reached a settlement that actually moved forward to significantly advance funding for infrastructure across the United States. And I think the challenge for us is to get our car companies to put as many advertisements for electric vehicles as they do for trucks. When we do that change will happen in this country.

Greg Dalton: Well they make more money on trucks.

Gina McCarthy: Yeah, well then they gonna have to probably recognize that they’re going to seed the car market to companies like BYD in China. When they start competing here in the EU they have actually right now really good technology to be able to sell. And our car companies I just hope they recognize that and realize that regulations aren’t driving their market right now the other countries who are investing in a low carbon future are actually going to drive that market. And if they want to be competitive they have a lot more to worry about than regulatory standards.

Greg Dalton: So world on target to meet the Paris goals?

Gina McCarthy: Is the world on target? It does not look like it. But the Paris you know one of the great parts about the Paris agreement was ingested and got everybody to the table well, now almost everybody. But it also understood that it would need to be adjusted over time. You know they need to put in plans we need to see how they worked. You know, I think we’re not off to an aggressive start button but countries are still at the table and they’re still rolling up their sleeves. You know one of the things that the United States really pushed for in the Paris agreement was something called the capacity building fund. Which means that now that the developing world is really going to engage itself which it needs too because the developing world will soon be the majority of greenhouse gases being emitted will come from the developing world. We need to help support those efforts, and other countries to develop plans that allow them to do what we have done. Which is really to recognize that there are some significant benefits to moving towards carbon reductions and to leapfrog over some of the older technology choices that no longer provide as clean a world and as many protections of public health as we have used in the past. So hopefully we’ll have an ability to catch up. But there is no question that the challenge of climate change remains daunting.

Greg Dalton: There’s very little appetite now for rich countries to pay poor countries to help clean up the problem the rich countries created.

Gina McCarthy: Well this is one of the reasons why I’m at the Harvard School of Public Health, right because I couldn't agree with you more. The developing world wants to get people out of poverty as China has been working. And they want to then move towards a much more stable economic footing for everybody. I mean like anybody else would. So here’s the challenge. You can't go in and say well, excuse me, let's just look at carbon pollution that the developed world has created as a problem and help us fix that. I think there's a way to do this though because if you look at how the developing world is actually moving forward. Everybody is moving to urban areas. The air quality in those urban areas looks very much like the air quality in Los Angeles a long time ago or Pittsfield or Tulsa, Oklahoma. We learned then that you can't expect people to think that the economy is great if they are choking on poor air quality. So what if we did this. What if we instead of going over to them and saying okay, let's talk climate change. Why don’t let’s talk air pollution.

Greg Dalton: Health. Yeah. The health frame not the environmental frame.

Gina McCarthy: Absolutely. But if you do that you will allow them to continue their efforts to move people out of poverty. You will save lives. You will empower those communities and they’ll demand the same kind of future that we are demanding. They will want to see it and every time you reduce air pollution you are taking carbon with it. So I think instead of thinking about how carbon pollution reductions are bringing health benefits. We ought to drive in the developing world health benefits that are bringing carbon co-benefits. There’s a way we can do this. But you're absolutely right. The developed countries need to provide the assistance for the developing world to engage and to see a future for themselves that is just as bright with strong economies as we have had in the past.

Announcer: Former EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy, talking to Geg Dalton about climate change and public health. This is Climate One. Although McCarthy left EPA at the end of the Obama administration, many agency staffers stayed on – for a time – as the new administration took office. Lynda Deschambult [dee-sham-boh] was an EPA staff scientist working on Superfund sites until she left the agency in late 2017 after nearly 20 years. She spoke to Greg about what it was like to work for an agency whose mission was not embraced by the new administrator.

Greg Dalton: One of the first things that Scott Pruitt did as head of the EPA as he issued a Superfund memo how do that affect the job that you were doing at EPA?

Lynda Deschambault: Well a lot of us read that very carefully. And I literally did a word search on it. I remember to see how many times the words protection or environment were in there because we immediately had a sense of skepticism. We all know Scott Pruitt's background and he sued the EPA 13 times before he was put in charge of it. So we were like, hmm what’s this gonna be all about. And it was an odd, odd memo and didn't really come across convincing to a lot of the scientists and didn't really come across strongly in our opinion of the mission of the agency to protect human health and the environment.

Greg Dalton: You worked for a year under Scott Pruitt, the Scott Pruitt EPA. What's the feeling, what’s the mood like inside?

Lynda Deschambault: Inside is a very somber. The agency had already experienced a lot of hiring freezes under previous administrations, they’d already had cuts and cutbacks in their jobs and people were just sort of dumbfounded that this sudden, you know, switch where suddenly we had the people we were regulating were now the regulators. So the appointment of Scott Pruitt was rather dumbfounding to most, and left a lot of people very almost numb.

Greg Dalton: I was hoping you might say that a smaller EPA may be a good, a better EPA that bigger is not necessarily better when it comes to government agency.

Lynda Deschambault: That may be true but it was already a smaller EPA before Scott Pruitt came in. This has been going on for a long time. This attack, this war on EPA is not new. I mean the cuts had been coming slowly over time. So it was pretty hard hit.

Greg Dalton: And you said that people are polishing their resumes, lawyers preparing to take the bar exam, are people planning their exit?

Lynda Deschambault: Well I'm in the trenches and I'm not there now. But from the people I've had coffee with or talked to and even the days just before I left, I did in fact hear that. The term I heard was the inflating their lifeboat and a lot of people are preparing and worried that their jobs are at risk and looking at other options. The agency hired a number of new young people between the election and inauguration day. They hired a number of young people anticipating a hiring freeze coming up. And I've been told that already a handful of those people are worried because they are last in and are starting to look at, you know, leaving the agency as well.

Greg Dalton: You’ve also said, what, drug tests and other things that you haven’t seen before in you’re almost 20 years at EPA.

Lynda Deschambault: I didn’t have the first experience. We do get health tested and drug tested. But a recent team of former EPA employees got in, one of the managers at headquarters said that people were literally being tapped on the shoulder and taken out for drug tests. And one of the other managers in that meeting with the union said they had never seen that before. And I've never experienced that other than our annual. So there's sort of this I don’t know fear mongering, something going on around that we had never seen before.

Greg Dalton: There’s been a lot written about scrubbing of climate science from the EPA website and science under attack. Did you experience, were you ever instructed to go light or not use science in a certain way?

Lynda Deschambault: Not on the issue of climate change so much. I did do some of that work when I was in a leadership development program. And I didn't have firsthand knowledge of what they were doing because I was a staff person, a project manager in Superfund. But I did see some of that in the Superfund happening. I was told not to have any more community meetings. It was suggested that I not finish a community fact sheet that I was working on. And in general, there did seem to be a shift where the decision-making was taken away from the scientists and engineers. So in the past they would come to the project manager and ask for our opinion on things. The lean process for instance, was discussed with me and I identified some opportunities where they might want to use that in expediting how quickly the responsible party got us the data. For instance, it had been over a year since the fish had been tested in the area and we hadn’t received the data back. I had suggested we might want to be efficient in expediting how fast the responsible parties payback EPA. And all those decisions from a scientific or a project manager engineer was pushed back up to management as recommendations and they were not forwarded. And the decision-making was put in the hands of the managers and from top-down was informed that this process was going forward and that my suggestions were not going to be offered up or considered.

Greg Dalton: You went through the Clinton to Bush transition at EPA. How was the Obama to Trump transition different?

Lynda Deschambault: You know I was surprised that when we transitioned it wasn't very, the administrator, the regional administrator we had at the time, Wayne Nastri ended up being a very good fit for Region 9, surprisingly. So the president appoints the regional administrators. And, you know, we did see maybe a little bit back off on enforcement and more compliance assistance. But he still had a lot of push for the science, for the mission of the agency to protect human health and the environment.

Greg Dalton: This was under President Bush. Region 9 being California, Nevada --

Lynda Deschambault: Arizona, Pacific Islands, Pacific Northwest. So it was not as bad as some of us had thought. And we weathered that storm and it wasn't even that much of a storm. I thought the appointed regional administrator, you know, did a decent job and the decision-making was still being left to the project managers and those of scientists and engineers in the trenches were still --

Greg Dalton: You got to do your job.

Lynda Deschambault: -- calling the shots. I mean we were told to, you know, tighten our belts and the term they were throwing around was it's time to do more with less. And that we needed to be efficient and, you know. So we saw some of that but it was still up to us to do it. And during the second term of the Bush administration, the term literally changed. Okay, it's time to do less with less because more cuts are coming. And that still meant now do your job but prioritize. And we were still deciding in letting management know what the priorities were and what less, what less meant and what we thought the job should focus on.

Greg Dalton: And then from Obama to Trump, how does that compare?

Lynda Deschambault: So that was a big switch. So now it was almost don't do your job and put on your cloaks of invisibility and back off and stay tuned.

Greg Dalton: Walk and wink you say, yeah.

Lynda Deschambault: That was a term that one of my colleagues used and I guess it's been used in the industry before is wink and walk. So like it’s the site is clean enough and we can move on. But, yeah, it definitely felt very different.

Greg Dalton: And when did you plan to retire?

Lynda Deschambault: In about six or seven years.

Greg Dalton: And why did you retire at the end of 2017?

Lynda Deschambault: Well that's what the local community group and tribe asked me as well. And really the main answer I have is I didn't feel I was able to do my job anymore. I've always felt from when I made my career choices very young high school even junior high, I always wanted to work for something I could believe in and take care of the planet. And I always felt really good about my job. And I suddenly didn't feel I was where I wanted to be. I felt like I was working for the regulated community and because of this cloak of invisibility that was tossed over me and I didn't feel I could have much impact there anymore.

Greg Dalton: And how do you feel now you're out a month or two. Walking away from an agency where you spent 20 years of your life. How do you feel now?

Lynda Deschambault: It’s been interesting. It's been tough. Just before coming over here I met with a colleague from work and I really miss the community. EPA really has a tightknit group of experts who really have a passion and belief in the work they're doing. The amount of hours that people put in, the amount of things they do over time and that passion is you feel it, it’s a really lovely place to go to work every morning. I really loved my job. I loved going in there. And so I'm feeling a little bit of a loss.

Greg Dalton: Do you regret making the jump?

Lynda Deschambault: I don't have any regrets. The people I've talked to, the things I've heard, unusual training, unusual practices, unusual reprimands people are getting. I'm looking for other work and I'm sure that will come along and I am not looking backwards. I'm looking forward. And I think I will continue to fight for human health and the environment outside of the agency.

Announcer: Former EPA staff scientist Lynda Deschambault talking to Greg Dalton about leaving the agency after nearly 20 years. This is Climate One. Up next, we’ll hear about how the oil industry didn’t need to wait for the EPA to learn that its product caused harm.

Ben Franta: One of the reasons he gave for moving away from oil was this problem with climate change, with global warming. And that might have been something that the audience didn't quite expect to hear.

Announcer: That’s coming up, when Climate One continues.

Announcer: We continue now with Climate One. Many people look to James Hansen’s 1988 testimony in Congress as the moment when the fact of global warming became public knowledge. But a recently discovered document reveals another prominent scientist warning a gathering of oil executives about the same thing nearly three decades earlier.

Benjamin Franta has a PhD in Applied Physics from Harvard and is pursuing another PhD in history of science at Stanford. His research focuses on the history of climate politics. He spoke to Greg Dalton about a surprising discovery he made deep in an oil industry archive.

Greg Dalton: So Ben it’s 1959, Columbia University, and a man is walking up the iconic steps on Columbia University. Take us to that place. What’s happening?

Ben Franta: I actually looked up what the weather was like that day so I could say, oh it was sort of a typical day. Turned out you had this oil executive, Robert Dunlop and he was there. He was a guest speaker for this very special event. This event was the hundredth anniversary, the Centennial of the American oil industry. Because it turned out in 1859, almost exactly 100 years before, this very severe looking guy, he struck, well he dug deeper than most anybody had tried to dig before just outside of Titusville, Pennsylvania and hit a huge amount of oil. And when people saw that they thought this is gonna be a massive industry. And so a lot had changed in 100 years. By 1959, oil was instrumental in global commerce. It was a key factor in warfare. Two of the world wars had occurred and oil was key. And now you have people like Robert Dunlop who are not this rough and ready wildcatter but this fairly sophisticated businessman. And so he was there for this big celebration. But it wasn't just him there are all sorts of other people there too. From the transcript of that day, there were about 300 people there. And these were pretty important people. These were government officials. These were industry executives. These were historians and scientists and things like that.

Greg Dalton: So it’s 1959, Columbia University these well-to-do influential people and Robert Dunlop, the president of Sun Oil is there. And it's put on by the American Petroleum Institute and the Columbia Graduate School of Business. So what happens what's the headline at this convening on the hundredth anniversary of the oil industry?

Ben Franta: Yeah, so the headline is well what the conference is called Energy and Man. Two of these cosmic forces coming together where have we come from with energy, where are we going, what’s the energy of the future. And I find it interesting that Robert Dunlop in his speech he refers to energy as the prime mover. That's the way he frames it in pretty cosmic terms. And so it was part celebration and part looking ahead to the future and the future look pretty bright at the time.

Greg Dalton: And enter Edward Teller.

Ben Franta: Yes. So there is a little bit of I guess somebody spills the punch sort of thing. They invite one scientist to speak out of these five speakers, so five people stood up that day to address everybody. Robert Dunlop was one of them. He was the industry representative. There was an historian and then they chose a scientist, too. And out of all the scientists they could've chosen, they chose Edward Teller. And this sort of makes sense Edward Teller was pretty popular with the industry. He is sort of like a man's man of a scientist, you might say. He was a pretty big proponent of nuclear weapons, nuclear technology, in general.

Greg Dalton: He was inspiration for Dr. Strangelove.

Ben Franta: Yes, there are rumors or discussions yeah that he was the inspiration for Dr. Strangelove. I've read that he never really liked that comparison, which is understandable. And so he stood up and his topic was what's the energy of the future and it might not surprise you that he was promoting the use of nuclear power a great deal in his speech. But one of the reasons he gave for moving away from oil was this problem with climate change, with global warming with CO2 accumulating in the atmosphere. And that might have been something that the audience didn't quite expect to hear.

Greg Dalton: How did you find this, this was the first time I'd heard this, there been other reports about 1957 the American Chemical Society, you’re hearing about the greenhouse gas effect. How did you uncover this?

Ben Franta: I was at an archive in Delaware, Wilmington, Delaware it’s called the Hagley Museum and Library and it’s the old DuPont's manufacturing plant where they used to manufacture gunpowder for very long time I think even before the American Revolution. So I was there just looking through their materials that they had on the American Petroleum Institute because that's one of my main research interests. And it was the end of the summer it was my last day in the archive. It was actually my last few hours in the archive. And I thought well, I shouldn't waste this time I should do something with it. And so I looked through these materials that I haven't looked through yet, although I don't think I'm gonna find anything interesting in there. And so I was looking through this transcript of this conference and I thought, what are the chances that anything interesting will be in here. I thought very little, I’m just going through because I’d kick myself if I didn't go through it. And Edward Teller, that’s kind of interesting and read through it. And I thought, wait a second, like are you kidding me? And to be honest I sort of didn't know what to do with it. I kinda sat on it for a few months. And so finally I thought okay, I think I’ll publish this and see if people are interested.

Greg Dalton: And what's been the response?

Ben Franta: Well it's been bigger than I anticipated. I think what is so interesting about that story is that it is so poetically perfect in a way. It's not just the facts, because we know people are talking about climate change around then anyway. But it's the poetry, it’s the irony of this story that as the industry's birthday party really is what it was that they invite somebody to speak and they say, guess what, according to the latest science if you keep going on the way you’re going, New York City might end up underwater.

Greg Dalton: Here are some of Edward Teller’s words that Ben Franta found in the archive.

Male speaker: But I would like to mention another reason why we probably have to look for additional fuel supplies and this strangely is the question of contaminating the atmosphere. When you burn conventional fuel you create carbon dioxide. The carbon dioxide is invisible, it is transparent. You can't smell it. It's not dangerous to health. So why should one worry about it? It has been calculated that a temperature rise corresponding to a 10% increase in carbon dioxide will be sufficient to melt the ice cap and submerge New York. All the coastal cities would be covered and since a considerable percentage of the human race lives in coastal regions. I think that this chemical contamination is more serious than most people tend to believe.

Ben Franta: Now of course Teller might've been even a little pessimistic or overcautious compared to what we know today. But we always have to think about what was the state-of-the-art of the science at the time. And at this time this was essentially the state-of-the-art.

Greg Dalton: And for people who don't recall, Edward Teller went on to champion the Strategic Defense Initiative or “Star Wars.” He has this huge stature in the Cold War, a father of the hydrogen bomb. So really it's the resonance of the moment, but also the stature of who the messenger is.

Ben Franta: That’s right that's right. This is an unexpected messenger really.

Greg Dalton: Now he goes on in 1998, there's something called the Oregon Petition in which he walked it back later. So tell us of what you know about the Oregon Petition in 1998, which concluded “there is no convincing evidence” that CO2 or methane will disrupt the Earth's climate.

Ben Franta: So this is one of those curious cases where somebody moves to skepticism or they're skeptical about being alarmed about the problem in a way that's very contrary to how the rest of the scientific community moved. Now orne speculation I could offer is that like other very prominent scientist during the Cold War, Edward Teller didn't just have science on his mind. He had the role of government in his mind. He may have been worried about government regulation and maybe that led him to be more skeptical of global warming science later in life than he would've been otherwise.

Greg Dalton: In fact there’s been some other work in this area about the story of Cold War. The opposition to climate change really came out of free market ideology and Naomi Oreskes at Harvard, The Merchants of Doubt, traces this to some ideological roots. People supporting capitalism concerned about government intervention more than the simple story on the left, which is oh it’s financial interest of the oil industry. Which I think personally is oversimplified and too easy and not really nuance or accurate.

Ben Franta: Yeah. So there is sort of this debate that goes on about well, what is the origin and nature of what you might call the climate change counter-movement. The very organized effort to delay, block, obstruct efforts to address climate change and people have made arguments that it's financial and origin that it’s ideological origin. In my own research what I have usually found is that there are ideological components to it, but almost always virtually 100% of the time those ideological actors are supported financially. Their voices are amplified by commercial interests. And so what you have is actually a fusion I call like a twin thread that forms a rope between ideology and commercial interests. And they’re defined primarily by their concentrations of capital usually accumulated through business and their recognition that the only entity powerful enough to take that away from them is in fact the government. And so they that group this sort of plutocratic group has engaged in a very long effort to dismantle the regulatory state to avoid taxation and so on. And so for them attacking climate change policies is part of an ongoing project. And sometimes these overlap. For example, the Koch brothers is a great example where plutocratic interests overlap with commercial fossil fuel interests.

Greg Dalton: And that comes too today. You wrote recently in The Guardian that Trump’s comments about pulling out of the Paris Climate Accord echoed arguments made for the U.S. not going forward or pulling out of the Kyoto Protocol, which was never ratified in the United States. So tell us how those narratives keep recurring and coming up.

Ben Franta: Yeah. So when Trump pulled out of the Paris agreement he justified his decision by referencing an economic report those done by NERA Economic Consulting firm. Now if you look at who commissioned that report, the American Council for Capital Formation and some of the authors of that report that are same groups and the same people that the American Petroleum Institute hired to create very similar economic reports to justify the U.S. leaving the Kyoto process. So what you see is you see the same arguments the same talking points and the same people involved for a very long time. Now the reason this works is that people don't remember usually what happened 15 years before. Especially if it’s not widely advertised, who wrote something or who did something. And so I think one thing that history can really offer to the climate problem to fixing the climate problem is to say look, we have known about this climate issue for a very long time for many, many decades. How is it that we have made such unsatisfactory progress in dealing with it. These are some of the reasons these people these groups, these talking points, these strategies that create obstruction and delay. And when we see them again we should recognize them for what they are.

Greg Dalton: Why are they so effective?

Ben Franta: Well, what I think you have happening here is a story of capture of the government process capture of the regulatory process. And these stories, especially these ideological stories are often covers that are used to cover financial interests. So for example some interest let’s say they really don’t want a carbon tax or they don't want the United States entering the Kyoto Protocol. They have to come up with some way of justifying that position. They can do it through ideological language which people generally accept as being in the realm of personal opinions. You can have your ideology and that’s fine. Sort of more respectable than saying, well I don’t want this because this hurts my bottom line. They can also hire economists to write economic analyses and say this policy will destroy the economy. And now you have a tool to use for the rest of the American population. You can broadcast that to the public and say look, this is gonna destroy your livelihoods. Now never mind whether the economic analysis is actually true or not at that point, it doesn't really matter. You have the messaging point and you can use it to great effect.

Announcer: Greg Dalton has been talking to Benjamin Franta, a PhD candidate in history of science at Stanford. He recently wrote about his research on Edward Teller, the oil industry, and global warming in an article in the Guardian newspaper.

To hear all our Climate One conversations, subscribe to our podcast at our website: climateone.org, where you’ll also find photos, video clips and more. If you like the program, please let us know by writing a review on iTunes. And join us next time for another conversation about America’s energy, economy, and environment.

Greg Dalton: Climate One is a special project of The Commonwealth Club of California. Kelli Pennington directs our audience engagement. Carlos Manuel and Tyler Reed are the producers. The audio engineer is Mark Kirschner. Anny Celsi and Devon Strolovitch edit the show. I’m Greg Dalton, the Executive Producer and Host. The Commonwealth Club CEO is Dr. Gloria Duffy.

Climate One is presented in association with KQED Public Radio.