Greg Dalton: I'm Greg Dalton, and today on Climate One we're talking about climate on our brains. There's abundant evidence that our fossil fuel-driven lifestyles are frying the planet and driving weird weather people are experiencing everywhere. Yet, public concern about climate disruption has been declining in recent years, and even people who are alarmed about it are not doing as much as they could.

Over the next hour, we'll look at the psychology, language, and social cues that determine how people respond to human-caused climate disruption. We'll also talk about how people assess the risks that carbon pollution presents to their personal well-being, their children, their community and the economy.

Joining our live audience at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco, we're pleased to have two guests.

Dacher Keltner is professor of psychology at UC-Berkeley where he studies the social function of emotion, power and social behavior and negotiating morality.

George Marshall is author of "Don't Even Think About It: Why Our Brains are Wired to Ignore Climate Change." He's a former campaigner for Greenpeace and now a communications consultant based in Britain. Please welcome them to Climate One.

[Applause]

Thank you for coming.

George Marshall, do you recall when you first realized that climate change/climate disruption was a serious issue? And did you see it as a threat or an opportunity?

George Marshall: You know, I’m so glad you put that question that way because built into that question is the idea that there is a moment at which you have this point of awareness, and I think for many people there is, I mean in religious terms people call it an epiphany. And I think that's part and away of when I talk about in the book is what -- we’re so used because it comes from the language of science. They think of climate change as being -- just coming to us in the form of information that we somehow acquire as if by some osmosis that it just sinks in and -- when people don't get it, we just think, well, we just need to throw more information at them.

So for me, yes, I did indeed. In 1988 I went to a small public meeting. I was trapped living with my parents actually trying to get out and find a life for myself and I went along, and it was just in a small town while I lived in Britain. There was in a public meeting; I left absolutely shocked and devastated. The other thing which is remarkable, after this, how quickly that feeling passed. When I look around again -- this is really serious, I talked to people and no one seemed to know anything about it. There was no interest; everything was going on as usual. And then it was another 12 years before I started seriously working on it.

So, I think climate change is -- when it's a challenge or an opportunity or whatever, I think it's very much what we make of it. But the thing that I take from the lesson is that how we see it is very much in terms of what we're picking up from the people around us. We can feel whatever we like about it. But if you're not getting that support from the wider society outside, it's very hard to hold that conviction.

Greg Dalton: Dacher Keltner, did you come to it intellectually or emotionally? Do you remember?

Dacher Keltner: Well, I think I'm a testimony to what we're learning in the social sciences, which is that this issue really came to me emotionally. And as somebody who studies different species to make sense of where we came from evolutionarily, what really hit me early was the loss of species, and in particular the reducing populations of great primates in Africa. And that spoke to me really personally. And then, I think the information and the facts and the kinds of things that George represents in his book became ways of making sense of that initial emotional reaction.

George Marshall: One of the things which is a real challenge for climate change is that as a narrative, it does not have an enemy with the intention to cause harm. None of us seek to cause harm through the things which cause climate change, which is living our lives or we're driving our kids to school or we're having a holiday or we're visiting our sick sister or something. There's no intention -- there's often an intention to do good.

So, when we say that these things are harmful it creates a lot of -- it's a heavy emotional load and it creates a lot of tension for people. So, in the absence of an enemy with intention to cause harm, I'm afraid that we know from the way that our brains do with narratives. But missing parts of narratives are like a vacuum that seeks to be filled. And therefore, indeed what happens is that people slot an enemy into that narrative. They will bring one in.

On my own side, on the environmental side, I think we have over-emphasized the role of the disinformation campaign or the oil oligarchs funding misinformation. I'm not saying these aren't serious problems, but I'm saying I think we've done that because we're so drawn towards enemies. I think we've been quite fast to demonize all companies which are doing some seriously negligent things. But that is also a way of playing down our own culpability unless prove a way that we live. And of course, people on the right respond to all of that by slotting people like me into the narrative, making us into the enemy.

And therefore, we're just getting to this head to head with one set of enemies against another. Again as I said, but the narrative structure we create around climate change becomes the issue. And that becomes the thing which people say "I believe in climate change" or "I don't believe in climate change." It's the story that's being built around it.

Greg Dalton: And there's lots of environmental organizations, their business model and their funding is often based on having an enemy, you know, these -- "write us a check and we'll fight these demons; we'll fight these bad guys," right?

George Marshall: Yes. And I don't want to -- but I don't want to put that down, either. I understand that's not just the cynical exercise in fund-raising. That's a genuine attempt to make sense of a very, very complex issue by creating points of pressure where you think you can make change. I mean that is the nature of campaigning, is you can't go after everybody all the time, so you try to see where you can do it. But it's to say, the danger is however, that that then becomes the focus of the issue, and it's particularly dangerous in that I think we have this extraordinary partisan divide on this, where climate change has become so identified with your political identity that when we play these enemy games, we are just reinforcing the divide which really shouldn't be there. Really this should be an issue where we're finding common ground between people of different political world views.

But of course if we keep saying, "well, this is the enemy and you are the enemy," then of course people who identify with that side are going to say, "no, you're the enemy," and you lose sight of the story.

Greg Dalton: Gets to tribes and social cues.

Dacher Keltner, you want to comment on that?

Dacher Keltner: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, one of the interesting challenges that George poses in his book is what kind of narratives can we construct about this issue to kind of bridge the partisan divide. And what we're learning from the social science is first of all, that is a really important piece of advice because we have this story-telling brain that really is moved by stories, even in some studies more than facts and hard statistical data, which people don't intuitively grasp.

Really, another interesting issue to think about and there's recent social scientific work on this is that a lot of the classic narratives about climate change have to do with harm and care, right? We want to take care of vulnerable species or take care of the environment or the loss of parts of our ecosystems. And that narrative is probably appealing to this audience, and in general, to one side of the partisan divide, liberals. And there's recent work in moral psychology showing that climate deniers will actually be more moved by arguments and advocate for policies if the issue is framed in terms of purity, which is a very compelling moral frame for people of a more conservative political persuasion.

So if you talk about climate change in terms of the degradation of water, the pollution if you will, and couch it in those terms, you actually see shifts -- you see a closing of that partisan divide, which I think, it's a part of a challenge of your book, is to think about sort of tailored narratives that will help the cause.

George Marshall: Here's another example. As we know, Dacher, from the research in another area which is a difference in the -- this is kind of the moral foundation theory between left and right, it's attitudes towards authority. And authority is also a very powerful frame for people of the right.

So, if we run campaigns that say climate change is the opportunity to overthrow the social order, were immediately working against the set of frames of this. On the other hand, if have an argument that climate change is a chance to actually create a sense of common purpose where we can actually work together and we can have a much stronger sense of value. If we build, for example on the values of what brings us all together, we're speaking much more strongly to that sense of social security, which is important really.

Greg Dalton: But isn't there a lot of companies, a lot of powerful interests make their money from extracting and burning fossil fuels. So, aren't they inherently institutionally, perhaps individually threatened by saying that it has to change?

George Marshall?

George Marshall: I think climate change is deeply threatening. I think that that is of course the reason why people of the right and some very powerful economic interests are deeply challenged by it. There's no question about that. I mean, there is -- these divides don’t appear just because of the words that people use. They appear because climate change is fundamentally threatening. That's why I said that's why environmentalists and people of the left have been much more keen to pick up the issue. That does not mean however that we cannot find ways of talking about it. We'd speak to common purpose rather than some kind of head-to-head battle.

Greg Dalton: There's a quote in the book that -- from Carl Jung: "If there's an enemy, it is really our shadow, our internal greedy child whom we don't wish to acknowledge and who compels us to protect our own unacceptable -- to project our own unacceptable attributes onto others." So, are we the enemy? Are we demonizing oil companies, but it's really some shadow of ourselves,

George Marshall? I can get back with

Dacher Keltner on that.

George Marshall: Yeah. Bill Blakemore, the correspondent for ABC, actually had a very nice way of doing it. He's talked about this a long time. And he said, you know, we often talk about climate change as the enemy in the room.

And he says, "Well, it’s the enemy we’re inside.” We're in the middle of this thing, in that we are all in various ways challenged by this, and it’s -- and we’re all in various ways involved with it. Of course, we're all in various ways finding collective alibis for it, and I think that's also part of the process which feeds us to point in other directions. But there's a much more positive spin on this, which is, say yes, we can develop and grow as people, we can actually look at things which are really important to us in terms of our social relations and the way we live and our collective happiness out of a low-carbon society.

Greg Dalton: Dacher Keltner, I want to get you on that conflict, where people feel guilty, like "I'm part of the problem." It's easier to just ignore the problem than to look at that.

Dacher Keltner: Yeah, it is, but you know, and just to reflect on what George is saying, I think we are hesitant to approach the problem because it taps into so many of our basic habits and tendencies, right? To get into a car, to search for consumer products that will make us happy and the like.

But I also feel that there's a positive spin here, which is that yeah, we have these self-interested tendencies that can sort of feed into these social practices and economic practices that are bad for the environment. But we also have a lot of new science that suggests an amazing capacity to sacrifice. And we know shifts in social behaviors that benefit others from a lot of different studies are actually good for your health, they're good to activate reward circuits in the brain, we can detail that if you like. And so I think if we can kind of rethink the enemy that we're trapped in and think about pathways out through these more nobler tendencies, I think there's a lot of movement to be had. So, I don't think it's inevitable at all.

Greg Dalton: So, that sounds like living like a European: smaller house, smaller car, lower income but they're happier people. Is that true,

George Marshall?

[Laughter]

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: You might be European for the next couple of months or years, but yes.

George Marshall: You know, I live in a small community in a rural part of Wales in Britain, by all of the social indices, one of the happiest places in Britain. It is not one of the richest, the most important thing there is a sense of social identification that people have. Whether a cultural identification or a sense of place, not the hyper-mobility, people live there their whole lives. And I do think that's what people are yearning for, and the people most desperately need. So, yes, it's fairly obvious about, but America has a much high level of energy use and resource use but it isn't measurably happier than Europe.

It's also true actually but in terms of the measurements of collective happiness, but these peaked in the early 70s. If we were to recognize -- but actually, if we were to go back to the living standards of the early 70s but also to the social systems that went with it, that we would have gone -- especially with modern technology -- we would go a very, very long way towards dealing with this climate change problem. So, we have people have this idea but it's all about going living in a cave. I don't -- of course, that's a generated narrative, isn't it? That's a way of putting the whole thing down and demonizing it, but actually the fact is that there are ways we can reinforce our own communities so that we can be much stronger with that.

Greg Dalton: If you're just joining us on Climate One today, we're talking about climate psychology and messaging and language. I'm Greg Dalton and my guests are

George Marshall, author of "Don't Even Think About It: Why Our Brains are Wired to Ignore Climate Change." And

Dacher Keltner, professor of psychology at UC Berkeley.

Let's talk about risk. People interact with risk in all sorts of ways in their daily lives from getting in a car -- usually now, social norm is putting on a seatbelt but when I grew up I never wore a seatbelt, smoking, et cetera.

So,

George Marshall, talk about risk in daily life and also how we process the risk of something as big as climate.

George Marshall: We are -- I mean there is a sense but we are wired in various ways to respond to different triggers, to respond to in terms of risks or certainly a sense of threat, and there's a great deal of research on that. We certainly know of what psychologists would call salience, it's a very huge part of it. Something which is happening now, something we can see very, very clearly. Something again, to go back to the earlier point, that is caused by visible enemy and a known enemy with an intention to cause harm. These things are immediately and completely compelling to us.

We're correspondingly not well set up for responding to issues that do not carry those tags. So, things which appear to be distant, things which are distributed, things which appear to be in the future, things which do not have clear enemies. So, there is a problem with this that we are -- that the kind of issues that we are set up to respond to through our long, long developments in history are not well met by issues like climate change.

Again, this is why things like narratives are so important because this is the way that we give it a shape and form of a threat but this is also potentially where the risk is. But I would add of course something that we do, is that we're actively seeking to avoid it. So, one of the things that we do is we quite deliberately construct narratives around it, which make it fall against those biases. We're pretty smart on this.

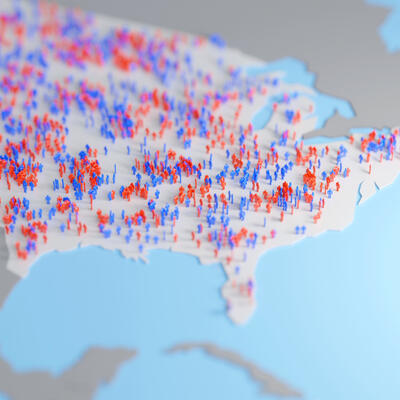

So, although climate change has been underway now for a hundred years -- it is clearly underway but there are major climate shifts happening, the vast majority of people are persuaded that climate change is something far in the future. Ten percent of people in America -- only ten percent think that climate change will seriously affect them. Over eighty percent think it will seriously affect the future generations. So that obviously includes a number of people who don't think it's happening at all. It's most peculiar.

It's a way of responding and shaping of things so that we know that there are issues we respond badly to in terms of risk, so we are deliberately shaping it in the form which is going to fail against those very biases.

Dacher Keltner: Yeah, I mean this is such an interesting place to draw on, the contemporary neural science. So, what we have in our brains is a part of our nervous system called the amygdala which triggers stress and cortisol and fight-or-flight behavior. And that's been crafted by tens, hundreds of millions of years to respond to what George is describing, which is immediate threats, probably dangerous objects, predators out in the environment, and not these abstract, long-lasting events that involve complex systems like climate change.

But what I would argue is that there are other parts of the brain -- the old brain that will drive the right kind of behavior that are capable of being activated by these arguments. Things like what E.O. Wilson talked about, the great naturalist, at Harvard -- that we have this love of nature and other species that has a lot of deep evolutionary roots that probably is driving a lot of the kind of behaviors that are good for the environment.

So, I think George's challenge again is to shift out of this risk narrative perhaps, which people don't -- we are woefully unable to appreciate risks and move to other kinds of frames.

George Marshall: I think the other thing that the recent cognitive research is showing is what the processes of disattention may, if anything, be more important than the processes of attention perhaps. So, the things which alert us to risk is one aspect. But the only way we can survive in an information-saturated world that we live in. Sitting here facing the room that may under historic conditions, contain as many people as I have met in my entire life in a hunter-gatherer group. I've been going out into the street, and dealing with San Francisco and dealing with the whole world and heaven knows watching American television.

Or an American football game. Is the game happening or isn't it happening? [Laughter] What's the status of it? So, we are extremely adept at not paying attention to things, or indeed just going okay, I don't need to worry about that anymore. We have an in-built bias to disregard things just to keep ourselves sane. So, it's partly that climate change doesn't carry the things that trigger that sense of attention but it's also partly that it has a number of things which trigger our dis-attention, and one of those is, like I said at the very beginning, my experience of being moved by climate change and then finding out that no one's talking about it. And that triggers dis-attention. You just go, well, this is not happening out in the wider social realm, and therefore, it doesn't exist.

Greg Dalton: Climate change has been framed as an issue for future generations. I'd like to talk about children. John Oliver, the comedian, said we can't be trusted with the future tense. And truly, we're not doing so well for stewarding for future generations. Is that a useful frame,

George Marshall? You said climate is here and now, it's not about polar bears and grandchildren. Let's talk about whether that responsibility for children, if that pulls on some strong evolutionary impulses in ourselves.

George Marshall: And the answer to that is yes, it should, if we already believe in the thing that is being pulled on. The research is fascinating on this, that it is -- when you actually look across the whole society and you account for the variables of education and education and gender and class and politics and so on, you'll find that actually consistently people without children will express greater concern about climate change than people with -- of the same group. But I wouldn't want to generalize across the whole world, but I certainly know this is the case in Canada and Britain and America. Not by a large margin, but enough to suggest that there is something which is going on there which leading people with children to suppress it.

Of course, what happens is people care about climate change care deeply about climate change and their children. People who do not care about climate change seemed to actively reject that because it contains a moral challenge, and of course in face of a moral challenge, you really seek to disavow that and push it away. But then of course, there's a large area of people in the middle who don't deal or talk about climate change at all. People without children are markedly reluctant to talk about climate change. They have some of the lowest indices of conversations about climate change. Young women who have children are the social group of all that are least inclined to talk about climate change.

So, I think there's two things. Let's put one thing which is very interesting which shows that this is very complex the way we engage where this is all goes through this -- is all evaluated by these moral challenges and whether we can handle it and whether we feel that we have a recourse to action which we haven't yet touched on. But I think the other thing which shows is that we're all extremely biased in our interpretation, not just of climate change, but what we think of winning arguments on climate change.

So, my campaigner friends are utterly persuaded that the things that work for them are the winning arguments. And we say, well, actually that's almost proof that it's the worst possible way of talking about it, you are so unusual. You have no idea of what's working out wider.

Greg Dalton: Dacher Keltner, children pull on some strong evolutionary impulse to protect?

Dacher Keltner: Yeah -- no, I think this -- I mean absolutely. I think parents, it's hard to talk about climate change to kids because there's an apocalyptic dimension to it, it's catastrophic. When I have the conversations about it with my daughters, literally one time it triggered an anxiety attack because, "oh, the world's coming to an end." But I think that's going to change, and in particular for a couple of kinds of data. And what we're learning in the health sciences is climate change is going to damage the nervous systems of people around the world.

So, we're starting to -- if anybody's been to Beijing, that's my research team recently did and the air quality there and what it's doing to the health distribution of those individuals, it's clear what we're finding in our lab at UC-Berkeley in partnership -- we're doing a project with the Sierra Club -- is one of the strongest predictors of a healthy immune system is having a healthy environment around you, a natural environment -- actually affects your nervous system. That health argument, and those data are expanding, will be very compelling to parents as they always are, that this is about the life expectancy of my child. And I think we'll be there in five years and that'll provide a different kind of platform for this discussion.

Greg Dalton: You talk about pollution in Beijing, which brings up the idea of severe weather. There's been severe weather. Whether it's Katrina, Sandy, record monsoons and typhoons in the Philippines, droughts, floods,

George Marshall, do people then take that and say, "wow, climate change is here; I better do something" or do they say, "that wasn't so bad." The New York subway flooded with the Atlantic Ocean, it's gone now -- have we all forgotten? We can just adapt to these things and keep on our merry lifestyle.

George Marshall: So you warned me you were on jargon alert but I'll introduce an important phrase from cognitive psychology, which is biased assimilation. The bias is what happens when you have existing points of view, you bring in around it the evidence in order to support your existing view. And it's clearly what happens around people's attitudes to extreme weather events. People who are inclined to accept that the weather is changing and inclined to -- and therefore, inclined to accept with it the entire package, which is what we've said before is a serious package requiring major change the way we live and the attitudes to work, most definitely, see extreme weather events as associated, even when the scientific evidence is not that strong that they’re directly caused by climate change.

And the converse is true. We see time and time again that the strongest correlation to people's attitude to extreme weather events comes down with political and partisan -- the political identity of people that are saying it. What was particularly surprising to me in research of this book because I had an opportunity to go on and speak to extreme weather survivors in America, I spoke with people in Central Texas where in the town of Bastrop or a third of them, the houses burned down. Huge wildfires under extreme heat conditions -- the hottest temperatures ever experienced in Bastrop County, and also along the coast of New Jersey. And I did a string of interviews and people were very -- what they wanted to tell me about was how validating the experience was in terms of a sense of community, how amazingly generous and warm people were -- people do come together under conditions of extreme weather events.

And then when they stay on in the area, they're voting in favor of the area, it's a positive vote for a positive outcome in the future. They are not in a position to want to take on board the possibility that this might be a regular occurrence and get worse.

Greg Dalton: So, severe weather builds community and makes people stronger. Okay.

Dacher Keltner?

Dacher Keltner: It does, but regrettably it also triggers this amazing capacity we have, which you know, I see documented in your book which is -- and has been documented in other kinds of responses to catastrophes as we rationalize the experience and justify the status quo. And we quickly say, you know, "well, I know I live right on the Hayward Fault and it tore up my house but Berkeley's precious and I'll stay and I'll be here." So, I think it's another one of these complex biases that the movement if you will has to really counter.

George Marshall: One of the people I interviewed is Paul Slovic, who's the world expert on social construction of risk. And I said, "Surely, Paul, climate change does meet the criteria that you identified for what should make people very concerned. It contains very, very dramatic events. It contains a fear. These are things at which people feel a lack of control, that the ultimate course is a technological.” These are all the issues here identified, which is making people terrified, for example, nuclear power stations like Three Mile Island and these kinds of events. And he said, "yes" -- but following what you said, Dacher -- he says "Yes, but the problem is that it comes in a form that is nonetheless familiar to people. That an extreme weather event may be very extreme, but it is still a weather event." He said, "If it turned the sky purple, it might feel differently."

But the problem is that not only we are both socially but we are also, from an evolutionary point of view, adapted to deal with these kinds of things and we are extremely adaptive, and part of that adaptive coping is the that we all come together and we rebuild. And so, already those narratives are in place which makes it hard for us to recognize that there is a consistently building threat.

Greg Dalton: We're talking about psychology and communication at Climate One today. Our guests are

George Marshall, author of "Don't Even Think About It: Why Our Brains are Wired to Ignore Climate Change," and

Dacher Keltner, professor of psychology at UC-Berkeley. I'm Greg Dalton.

Let's talk about a couple of fables, long held narratives -- The Boy Who Cried Wolf and Chicken Little; how do those work out [laughter] in a climate context?

George Marshall: You know, the interesting thing about the boy who cried wolf is he was right. [laughter] We forget that when we hear the story.

Greg Dalton: The wolf is there.

George Marshall: Yeah, the wolf is there. The wolf came and the wolf came and ate all the sheep. The wolf is there. The problem with the boy who called wolf is he became a distrusted communicator, because he kept crying. "The wolf is coming, the wolves are coming, the wolves are coming!" And then everyone went, ‘ah, we're not paying attention to you anymore,” and then the wolves came. So, although Aesop frames it as a story about lying, it's actually a story about communicated trust. If we keep saying it's the end, it's the end, and again with Chicken Little. Of course it's the end and the sky is falling, then there is a danger with that, that the trust of the communicator is lost.

I'd say also both of these stories are interesting. They're also interesting parables about social conformity. So, both the boy who cried wolf is the idea of the outsider who is calling on something. And outsiders who call on things are given credibility, it's interesting. We just assume that everybody follows everybody else, but they are. Same thing in chicken little, you know. Chicken Little, this one person says, "I've heard something," and this is -- "the sky is falling." And that person then creates a social conformity amongst people who follow him.

What's interesting with the way that the story builds is that one person says to another says to another says to another, and then this thing that is without evidence becomes a social fact. It's one of the things I talked about in the book that actually, you know, we think of climate change with scientific facts -- although to be honest, scientists are very wary about the word 'fact' -- but we think of it as being based in scientific facts but actually it's about social facts. So, chicken little is about that. The social facts but are generated through a rumorthat gets shared between people, it goes back really, it's about the thing but socially shared narratives will weigh more powerfully than the evidence behind them.

Greg Dalton: There's another person quoted in the book. Bob Inglis, former Republican congressman from North Carolina. He's been on the stage at Climate One. He was tossed out of Congress in part because he stood up and said, "I'm a Republican and I accept climate science." He was actually converted by his daughter. He was a climate change skeptic, his high school daughter came to him and said, "Dad, you got to look at this." He did. And

George Marshall, you quote him in the book as saying, "Listening to Greens is like seeing a Dacher who says 'oh my gosh, that's the biggest melanoma I've ever seen.'"

But how can people who are concerned about this, who are emotionally connected to climate change communicate it with people without being a prophet of doom?

George Marshall: It's actually interesting what Bob was talking, he also said that we were seen as being "gray pony-tailed bedwetters who get our knickers in a twist." [Laughter] I thought, yeah, that's interesting. I said, "Bob, I'm not gonna tell you what we said about people like you and your friends." [Laughter] Actually, Bob's got a good sense of humor. He's a good one. But it is true that there are problems, there are problems of telling people about how serious it is, but the more serious things become, the harder it is to communicate it. And I have to admit that even as somebody who does communications for living, I do not have a clear resolution for this. It is a constant debate within the environmental community and people are trying to do this about do we just -- do we actually talk about this in terms of the seriousness of a threat, hoping that we can trigger that threat response.

Certainly, maybe through a narrative rather than just presenting the data. Or do we realize that there's a point that people may not get triggered by that and that they may just simply go into a kind of disavowment. Similarly, there are people who say, "you know what, we don't need to talk about that at all; we can just simply talk about the opportunities, we can talk about the benefits of a low-carbon economy; we don't need to talk about that.

I'm afraid I have to say I think that this is just an area where individual communicators in their own groups will just have to find the balance. But I think what is interesting is what the nature of the threat, and again going back to this point about narratives, of how the story is told around the threat, is what will mobilize people. So, different threats register in different ways for different people. And really it's about pulling out both the positive benefits of the changes that we need to make and the threats in ways which speak clearly to the world views of the people we're speaking to. Not assuming that the Amazon burning down or Bangladesh going underwater or polar bears dying is something which is going to trigger with somebody who's just trying to put food on their table. Maybe for them it's going to be something which is much more direct and local in impact and concerning their community.

Greg Dalton: Dacher Keltner, how do you look at that balance between hope and fear as a psychologist and researcher?

Dacher Keltner: Well, I think we've detailed the fearful quality of this risk but then the disavowal fear that most of us have because of psychological reactions to fear, but I also think that there is -- people respond very powerfully to hope and to elevating narratives we know in the persuasion literature, so I take a great deal of hope in a lot of the social behaviors that are taking place. More people in the Bay Area are riding bicycles, people shopping locally, some of the classic issues in this field.

And one of the things I just want to elaborate upon that George was talking about, and it really is a challenge in the book, is the politicization of this issue makes it hard to talk about it with a lot of people. And across the book, you see these stunning examples of how people just will not make it a conversational topic, climate change. But what we know is, and from studies for example of social networks, is that to the extent that people just make it an everyday part of their social conversation, talk about different practices that they're engaged in, what you see in studies of neighborhoods is those habits are picked up very quickly by other people.

So, one theme of our day today is really sort of the emotional themes to the narratives. The other that comes out of your book very clearly is talk about it, or just make it part of family conversation today and in your community.

George Marshall: Yeah. So, in parallel to this process of attention and dis-attention that I said we have there’s also a process of conversation and non-conversation. And for a long time we've been thinking that the non-conversation climate change is just an absence of conversation. But it's clear that it isn't and there's a growing body of evidence that shows that it actually has its own shape and form, that there is a very socially created -- socially reinforced non-conversation which is happening. And you know, life is an experiment after all, and I'm sure any of you who care about climate change when you go and you talk with your friends or family or people who are not within the same -- maybe the same politics or world views yourself, you'll find this conversation, it just dies. You just put it out there and you say, "I think this drought is climate change." I mean you watch as this conversation just withers and dies or just mysteriously just start shooting off in a different direction. And those people who studied this have made analogies with the same way we have socially constructed silence around things which are far more morally challenging, like human rights abuses. But entire societies can enter into non-discussed and non-negotiated collective contracts about what can and cannot be recognized or what is appropriate to talk about.

I really think climate change is one of these areas like previous struggles over -- over social rights, disability, sexual abuse for example, where there is a socially constructed silence that has to be confronted. We know a third of people in recent polling couldn't recall a single conversation they had ever had with anyone about climate change. And the vast majority of everyone else only talks about it with very close family and friends, and indeed scarcely talk.

So yes, I think the greatest -- one of the greatest opportunities is, and one of the kind of take-homes from conversations like these is to recognize we all have powers as actors. As Dacher was saying, that we all in various ways influence the social norm of people around us, and that have to be open with this. We're convinced about this we have to say, "I'm convinced. I'm convinced." And just wear that openly in our social groups.

Greg Dalton: The identity can be very strong. One thing we haven't talked about is actions -- individual actions. How significant is it to compost, buy electric car, to live a green lifestyle, make green consumer choices.

George Marshall, are those significant in terms of identity and culture or are they trivial?

George Marshall: I think they're hugely important for our personal consistency in terms of dealing with this issue. I think if as -- so, let's assume now that I'm speaking to a concerned about climate change, I say, "if you're concerned about climate change and you recognize that there's a moral challenge but within this I think you have to face up to it and recognize that you have to have an internal consistency, that you have to recognize that in terms of the way that you personally live." Because otherwise, you're creating layers of bounded silence within yourself.

My colleagues in the environmental movement, they're very happy to talk about climate change, they're very uncomfortable talking about personal flying. There's a socially negotiated silence often around the aspect of our own lifestyle because -- and I flew here as well and I'm quite open about it but I had to. It was a long personal struggle to make that decision. So, I think we do have to do it. It's not just a matter of walking the walk; it's also vital for our own credibility as communicators. I think -- we denigrate the people who point to Al Gore’s fuel bills as if they were actively undermining somebody who is campaigning on climate change. Of course, that was politicized. But it's also understandable. People inspect integrity from communicators, because ultimately how are they going to judge the quality of what they say?

So, I feel that's really the basis for it. And also not to underestimate, as Dacher was saying earlier, the importance of these social messages, what we put out for our own behavior. The thing which gets people installing photovoltaics on the roof is the fact that they see the people around are doing it. It's as simple as that. It’s not the leaflet, or calls for action on climate change or polar bears. It's the fact that other people that they know and they like and they respect are doing it. And it's that social norm which generates the change.

Greg Dalton: And what have you done in Wales in your own lifestyle other than flying here? You've got solar panels in Wales? Do they have sunshine in Wales?

[Laughter]

George Marshall: Yeah, the solar panels rust before you get any power out of them. [laughter] No, actually strangely, we have solar panels right across Wales because the government is actively encouraging people to do it, and again, it's very interesting. In my own local community, I notice that people have been fighting against wind farms so they have solar panels all over their roofs. It's very interesting. People are happy to have solar panels because it's incentivized and they see a chance to get something, that there's a personal gain. So, there's a local narrative which speaks very well to people's sense of individuality, and the chance -- and thriftiness, which is a strong quality where I come from. And people resist the wind farms because basically it's being imposed by external corporations who want to extract the resources and make money out of it.

So, it's all entirely about how we build it. And yes, in answer to your questions, yes, I'm doing the very best I can to insulate my house. I heat entirely with wood pellets and so on. But that's also important for me to say to people -- actually, I realize how hard this stuff is, because there's real tendency to go out there and say, 'yeah, we can do this, we can do this, we can do this' while I can tell long stories about how hard it is and how the struggle is against the bureaucracy to get these things done. Because you know, we need to share that personal experience, right?

Greg Dalton: Dacher Keltner, how about your low-carbon lifestyle? Actually, low carbon -- George points out in his book that low is a bad word to use because it's considered low class, there’s all sorts of things about low. So, your high -- yeah, lifestyle…

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: There you go. That's a good --

Dacher Keltner: Well, you know, it includes a lot of the great sources of wisdom recommend which is avoiding the car and biking and walking and buying local, you know, reusing in terms of -- and recycling. And I think that one of the important things we've learned in the scientific study of social movements is that, as Desmond Tutu said, it often begins with minor actions of single individuals. And then there are all these dynamic properties that converge that shift social systems. And I hope that this kind of small actions will aggregate into something different.

George Marshall: But also, let's not think that the action is entirely about what you do or buy, because I think one of the dangerous fallacies created by the whole we've talked about climate change is that action on climate change is being pushed on us as if we're just individual consumers making the right ethical choices in terms of what we buy, which I think is a very cynical market-driven manipulation of what should be happening. And of course, ultimately extremely alienating.

If you say to people, your only power that you have is for purchasing decisions you make, it's not about the connections between the people. I think the real low-carbon choices I make are in terms of the investment I make into my friends and my family and the community around me. And if we talk about the solutions to climate change resting with the stronger bonds that we have between people, about doing things locally, about supporting the local economy, about doing things within our community, we're creating a story which is much more appealing across the board.

When we did focus groups across Wales, we found that these exciting stories, what people love about, the excitement of a new low-carbon revolution and how we're all going to have battery-powered cars and we're going to have solar panels all over our roofs, absolutely bombed with a large majority of people who, let's face it, are struggling just to keep up their mortgage payments. We’ve really got to avoid messages around climate change which just say, no, it's a different kind of consumerism.

Greg Dalton: We're talking about climate change at Climate One, I'm Greg Dalton. Our guests are

Dacher Keltner, professor of psychology at UC-Berkeley, and

George Marshall the author. Before we go to audience questions, there's one part of the book where I think there's a mistake, and that is -- you write that sex is a carbon-neutral activity. Now, that may be true in Britain, [laughter] but here you think about all the food and alcohol and all of the fossil fuels [laughter] that go into food and alcohol, leather involved, all of that. Okay.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: Let's go to our audience questions. Welcome to Climate One.

Female Participant: I was wondering if you could address perhaps briefly what role the government is playing in communicating? It seems that when people suffer earthquake or super-storms that the government at every level is right there. And do you think they would look at it differently if they knew that the state was not going to come in and FEMA was not going to come in and that they would be, to some extent, bailed out?

Greg Dalton: Who would like to tackle that? The nanny states, their force,

George Marshall?

George Marshall: You know, isn't it -- I find it really curious, it goes to how complex these things are but people who are so utterly resistant in their political world view of the government are so extremely insistent, but government comes in and supports in these moments of crisis. I think it just goes to show that people are very, rather than say we can assume how people feel about things, but actually, people's positions are very -- are indeed very emotionally driven. But there was a -- I think there is a real opportunity there for the government, that everyone who's involved with these things to make a point about longer term adaptation resilience around all of these extreme weather events. We know that whilst it might be hard to talk about climate change in terms of missions and responsibility in lifestyle and all of these things which are challenging to people.

We know that if we talk about -- there's this something which is now happening and is real but we need to adapt to, we need to protect and prepare ourselves for, that we have -- we're speaking about the values which are much, much broader, about people coming together, again coming together in their communities and working together to protect and defend the values and the things which are important to them. I would like to see a lot, lot more of that.

Greg Dalton: Next question. Welcome.

Carter Brooks: I want to elaborate on this individual action question. It’s my own personal belief, we have a little bit of an overemphasis on people's individual actions. We tend to promote the solution to climate change as everybody's behavior changing, when in fact, perhaps another way of looking at the situation is that there's a larger system at play. Humanity itself is an emergent system. Civilization as an organism perhaps is consuming the resources of the planet. So, the actions we need are perhaps larger systems, societal kind of changes, yet we so emphasize what individuals need to do or walk their talk and there's a little bit of a disconnect between the emotional energy we're supposed to put on that in that conversation versus what we can mathematically say is our actual contribution to the problem. So I wonder -- the question being then, what is the potential to shift the focus more to the collective action and recognize this issue around the overemphasis on individual action?

Dacher Keltner: Yeah, I mean one of the challenges that George brings up is -- and you're absolutely right in the ontological, philosophical sense. It is a systemic problem. But we've got to find narratives that appeal to particular cultural mindsets and I think the individual action is very appealing, and a lot of data support this, to kind of a more Western European individualistic mindset. I think in China it's going to be much easier to implement broad social interventions responsive to climate issues that are about duty, right, or about advancing the collective.

But that argument, although right, is going to face resistance, I think in parts of the West. So, we need multiple approaches to this.

George Marshall: And on that theme of multiple approaches, I want to also be very clear that although in the book I'm trying to outlay the psychological map as it were how we engage with this -- I really want to avoid saying we can only talk about it one way or another or there's only one set of solutions or another set of solutions, because clearly there is an argument that we need a huge scale of systemic change on this. And that if we just focus on, well, it's just a matter of finding the right words to speak to trigger people's psychology, that isn't going to work against the overwhelming scale of this. I think we do have to deal with people's personal attitudes and behavior because I think ultimately in a democratic society, it is what happens at higher levels in terms of corporate and government decision-making is built on the attitudes of people at the bottom.

I don’t want to rule that out. And I actually think that the excessive focus on personal behavior has been a sleight of hand actually on peoplewho are in positions, of higher authority to say, "You know what, it's your fault. You sort it out, it's your fault. We're just gonna keep business as usual." But this is all somehow going to be mediated through the market mechanism of your personal choices. I think that's a serious piece of misinformation we should be quite angry about.

Greg Dalton: Let's get to our next audience question on Climate One.

David Styer: Hi, my name is David Styer. My question is that I came to the realization that climate change is almost a moral issue. It's not an intellectual or an emotional issue. And I think about, you know, the struggle for civil rights in the South and how we were able to change as a society and make deep extensive changes. I’m wondering if there's been research about other social movements and how they've been successful in adopting change and what that can do for climate change.

Dacher Keltner: Yeah, there are two great observations embedded in your question. One is what makes social movements successful? And you know, here we have a really interesting social scientific and historical study of all the different kinds of social movements, protest movements against police issues like in Ferguson, wage issues, employment issues. And George is right, I mean it is the passions that drive social change. And that raises the challenge for the climate change movement, which is what passions are really going to move people?

And then the second issue again is that each of these social movements really revolve around different moral themes. And one of the things we've learned from moral psychology that you've cited earlier is there are many different moral themes that will resonate given your particular cultural background, your temperament and the like. And that again is another multi-approach, multi-language challenge is for some people, it really is about harm and care, for other people it's about cleanliness and purity. But passion is a good bet.

George Marshall: You know, one of the people I interviewed for the book, although I actually kept that interview for another piece of work was Alan Hochschild, who wrote a fantastic book, "Breaking the Chains," about the history of the slave movement, which started -- he described it as seven people sitting in a room deciding that they were going to end the most profitable and most vested interest trade in human history, of trading slaves, and achieving it within their lifetime. But what was interesting about those people was that many of them were coming from what we would regard as being deeply conservative backgrounds. That movement was built on a moral crusade that worked its way through the British churches, that people are saying, "this is wrong and we're going to stand up and we're going to oppose this." We'll also say that it was based on -- and this is the challenge for climate change. It was based on clear enemies with the intention to cause harm.

It was based on very, very powerful, deeply moving personal human stories. So, I think we do have to find ways where we can reach a balance. And the balance as I said, is a hard one where we can manage to find the things as Dacher was saying, which are deeply moving and compelling to people, without falling into the trap of making them so particular to one world view or another that actually we alienate some of the people who should be supporting the campaign.

Greg Dalton: And Robert Kennedy Jr. has written about slave re-transition, it didn't tank the economy as a lot of opponents said it would. Also,

George Marshall points out that Martin Luther King's speech is "I have a dream" not "I have a nightmare," so the hope is built into this. [laughter] Let's go to our next question.

Peter Joseph: My name is Peter Joseph and I work with Citizens' Climate lobby. And the one thing that we haven't talked about this whole time is money, and the factor of money, the fact that all of us burning fossil fuels are getting away with polluting for free, because all those external costs are not reflected in the price. And money is the most powerful human motivator on the planet, maybe love is second, but -- what would happen to people's thinking and their aversion to taking on this issue if they knew that we could harness the world's economy to solve this problem with a little tweak in the tax code that put a price on carbon, and then took all that money and gave it right back to people so they could afford the energy transition that we need?

Greg Dalton: Financial incentives. Who'd like to tackle that?

Dacher Keltner? Money -- motivator?

Dacher Keltner: It is a big motivator but I think the social benefits of pro social behaviors we're finding in different kinds of laboratory studies are just as powerful, often more powerful, so I think we kind to have to shed ourselves of that mindset. But I'd love to hear George's response to your policy question.

George Marshall: Yes, I also want to emphasize that as we know, money is actually tied up with the values of what money is and what it does. Does it bestow status, is it something which enables you to be a better parent or a better mother or be more successful in your society? So, money is actually often the medium of values, and they might be a way of going straight to those values. I will say though, having just come down yesterday from British Columbia -- British Columbia has had a very interesting experiment, along exactly the lines of what you're saying, a policy experiment with that.

And there is an opportunity, I think, in policy terms to be able to make a transfer from putting money on the price of fuel but making it a revenue-neutral tax and not building more government but actually returning to people in some way or doing something with it which is not directly related, just pumping into government coffers, around which I am convinced that there's a possibility of building across parties an agreement. Personally, although stepping outside of my book, I think that it's been a policy disaster that we followed these market-based strategies which seem to be far more based on a political world view, an ideology and actually without any evidence that they work one.

Greg Dalton: Next question.

George Marshall: There's two people on the queue; you can't get in there. [Laughter]

Dave Madison: Speaking of other possible frames, one of our leaders is talking about shifting the public climate paradigm and policy from fear-increasing to goal-oriented, thinking that climate work over the last 40 years has generally been focused on fear leading to collective action at some point.

Greg Dalton: So let's get their response to that. We got goals rather than sort of emotions.

Dacher Keltner: I think it's really sound. I mean we know -- people have been interested in what can change people's minds for a long time in the persuasion literature, and a certain amount of fear works, but once you cross, at midpoint it's bad news, people freeze up. We also know goals are subserved by big parts of our nervous system like the dopamine system which gets people doing things. There are a lot of terrific social psychological studies showing -- just get people thinking about specific goals, and they'll take action. So, I think it’s this kind of frame switch that George has been encouraging us, that would be useful.

Greg Dalton: Just one footnote. The international negotiations on climate are moving away from sort of one treaty where everybody has to be bound it for each country having their individual goals, and kind of in that direction. Let's have our next question.

Male Participant: Quick question on media coverage of climate change in the United States. You know, if a show like Meet the Press discusses climate change, they have one representative of pro-climate change and one climate change denial, and they are considering that balanced coverage because they both have five minutes. What are your thoughts on media coverage of climate change?

Greg Dalton: George Marshall, you point out in the book that we don't survey economists to say whether there is a recession but somehow this 97 percent of scientists versus three percent of scientists happens in climate and doesn't happen in other realms.

George Marshall: Yes. Well, the language of science which understandably, the professionalism of science is about expressing due caution, of course enters into a whole discussion. But it is a manipulated discussion. I mean this is the area where we should recognize that there are some very powerful vested interests and some very serious money which is put into this in order to create a sense of a false debate.

I think that the media does have a serious responsibility for this, for actually being seriously negligent in the way that they have portrayed the level of the consensus on this. Seriously irresponsible, not showing the personal political affiliations for people they have in their programs, and I really think it's one of the things that we as citizens can do is if we think that there is bias there or actually go directly to them and say this is not acceptable.

But I think there's actually an even bigger concern of the media which is the non-conversation about climate change. The absence of conversation sometimes completely, 2010 it almost completely disappeared, there was almost no coverage at all, and I think it's -- anyone who's in the media, I think it's very important for when we get things which point to climate change like extreme weather events for example, to go out there and get an opinion, is this climate change or not? And let's keep that discussion up and active.

Greg Dalton: The Weather Channel and some others are increasingly doing that. We're talking at Climate One today with

George Marshall, an author, and

Dacher Keltner, professor of psychology at UC-Berkeley. I'm Greg Dalton. Next question.

Male Participant: How could the scientific community change its narrative, the Chicken Little narrative, to change the social narrative? Or do you think it's even their responsibility?

Dacher Keltner: Yeah. I mean, so what -- this issue has faced in different scientific realms and one of the things we've learned is facts become highly polarizing and even the word 'fact' and statistical evidence, and people shut down, right? Even though that they are the foundation of our discipline and we need great storytellers. And the great storytellers like Charles Darwin in the field of evolution, that was really a fact-based narrative that shifted Victorian mindsets to really a radically different set of beliefs. And the data are really clear that great stories are what convince people. They can be fact-based but they have to be character-driven stories.

George Marshall: I will say that my organization, Oxford works quite a lot with climate scientists. We help advise and we speak a lot with them. And one of the things I am always keen to see them do is to create more of a story about themselves and about their work. They're doing very -- sometimes very brave and exciting work in the far corners of the world. They underestimate the importance that we place in our communicators of knowing and trusting our communicators and the integrity of our communicators. So, an awful lot of science communication is absent of individuals. And I love it when scientists step forward. They are still honest and faithful to the professionalism of their work, but they are also stepping forward in terms of expressing their own personal conviction and persuasion and their own back story about who they are when they step out from behind the curtain, they say, "This is who we are."

Greg Dalton: Something the other side has done very, very well.

Greg Dalton: With coal miners or that sort of thing.

George Marshall: Well, and their own scientists of course, like people who seek to undermine the science are constantly promoting the integrity and the intelligence and the extreme professionalism of the people on their side.

Greg Dalton: We have question from the audience at Climate One.

David Rosenfeld: I'm curious with -- communication I think is changing pretty dramatically now with the internet and social media. And you haven't really mentioned that at all as any kind of attitude changer or a way of progressing toward progress here and I'm wondering how that might play a role in changing people's attitudes and coming together for --

Dacher Keltner: Well, I think that really, really exciting new studies that show that elevating narratives, right, elevating stories that have some inspiration that's built into them, goals if you will, are what are viral, and there are very interesting stories about that, and I think that dovetails with one of the central theme today, is find those great narratives that move people and inspire action.

George Marshall: And one of the other themes is about people take as fact as truth what they see, the people around them in their own social networks, seeing and holding. So that means that new forms of social media become extremely powerful as ways of conveying new forms of socially held facts and new social norms. So, please, again, I don't know of anyone who cares about this please, use these themes, and share your personal conviction and persuasion on climate change with people in your own networks. And don't underestimate how important and powerful that is.

Greg Dalton: We tend to have a reliance on facts. We'll close here with just one quote in the book by

George Marshall, from, I believe it's Clyde Hamilton who says "Denial is due to a surplus of culture rather than a deficit of information."

We have to end it there. I'm Greg Dalton. We've been talking with

Dacher Keltner, professor of psychology at UC-Berkeley, and

George Marshall, author of the book "Don't Even Think About It: Why Our Brains are Wired to Ignore Climate Change."

Free podcasts of this and other Climate One programs are available on the iTunes Store. Thank you to our audience here at the Commonwealth Club and on the radio, thank you all for coming.

[Applause]

[END]