Greg Dalton: Welcome to Climate One from the Commonwealth Club, a conversation about America's energy, economy, and environment. To understand any of them, you have to understand them all. Today, we're discussing food and the global economy with U.S. Secretary of Agriculture

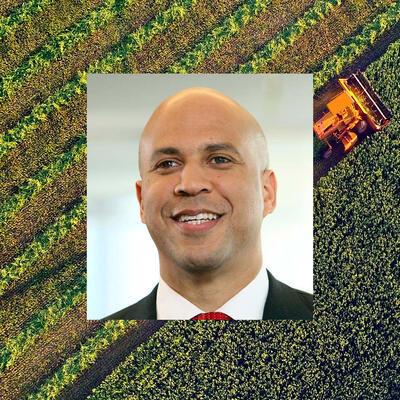

Tom Vilsack and U.S. Trade Representative

Michael Froman. I'm Greg Dalton.

The Obama administration is pushing to advance two of its priorities before the end of the year: a free trade deal with Asia and a foreign bill that steers American food and agriculture for the next five years. Both efforts are controversial in Washington and around the country. Over the next hour, we will discuss the future of food and trade in the era of increasing severe weather that is driven by burning of fossil fuels. Along the way, we'll include live questions from our audience at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco. Prior to becoming America's top trade envoy,

Michael Froman served as Assistant to the President for International Economic Affairs. He also worked for a number of years at Citigroup.

Tom Vilsack was Governor of Iowa from 1999 until 2007, and previously was a member of the Iowa State Senate.

Please welcome Ambassador Froman and Secretary Vilsack to the Commonwealth Club.

[Applause]

Secretary Vilsack, let's begin with you. Tell us about the Farm Bill and why it's important. A lot of people — if you're not in agriculture, you don't know about the Farm Bill. Tell us about it and why it's important.

Tom Vilsack: Well, the Farm Bill is more than a farm bill. It is a food bill because it provides assistance for struggling families, but it also assures that America has a great diversity and affordability of food, that we remain a food and secure nation.

It's a jobs bill because it invests in expanded opportunities in rural areas, manufacturing opportunities for example. It's an infrastructure bill because we invest in water projects, in utility lines, in broadband expansion. It's a trade bill because it contains trade promotion programs to allow us to continue to export American agricultural products around the world that we enjoy a record year in exports. It's a conservation bill. In this particular bill, it's going to streamline conservation programs that will allow us to have better soil health and better quality and quantity of water. And it's also a reform bill. This particular bill will substantially reduce the amount we spend in the farm support by eliminating direct payment program and focusing more on crop insurance and other risk management tools.

So, it's a very expansive bill and often doesn't get fully appreciated by Americans because it does impact every single one of us.

Greg Dalton: These bills happen every five years. Earlier this year, it was extended for a year as part of the fiscal cliff negotiations. My understanding is if it doesn't pass by January, we go back to the 1940s in terms of some prices, et cetera. So, is it going to get done?

Tom Vilsack: Well, it needs to get done. It needs to get done for the benefits that it can have for rural America. While we've had the best farm economy in the last five years and probably in the history of the country, rural America has not done as well. We've had a population loss so we've had a continued and persistent poverty. So, this is an opportunity for us to address some of those concerns in rural America.

If we don't get it done before the end of the year, then as you indicated, permanent law comes into place and the USDA will start purchasing commodities — milk, cheese, butter — at highly inflated prices because of the nature of permanent law, which will create shortages in the grocery store and higher prices for consumers. Nobody wants that and it doesn't have to happen. And we need to get this done.

Greg Dalton: Ambassador Froman, another thing that the administration wants to get done before the end of the year is the Trans-Pacific Partnership; tell us what that is.

Michael Froman: Well, thanks Greg. First of all, it's nice to be back in the Bay Area. I was born and raised across the Bay and it's always nice to come back here.

Yes, we're engaged now in the negotiation of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which is a free trade agreement with 12 countries constituting about 40 percent of the global economy. And we're also engaged in negotiation with Europe for an agreement. We're also engaged in trying to reduce tariffs on information technology products, for opened up services markets, trying to facilitate trade at the border and get rid of unnecessary costs and delays for products at the border. And when I come back to the Bay Area, I'm reminded just how much California benefits from all of this. No state benefits more from exports than California. It's the number one exporter including in agriculture but across a lot of products; exports about a quarter of a trillion dollars in goods and services each year, and there are literally hundreds of thousands of jobs in California tied to and supported by exports.

And that's what it's all about. What we're trying to do to the Trans-Pacific Partnership is open up markets in some of the fastest-growing regions of the world, raising standards in labor, on environment, on access to medicines, on intellectual property rights, pretty new disciplines for the 21st century global economy. For example, there's been the emergence of state-owned enterprises around the world that have a dramatic impact on the ability of our firms, our private firms to compete.

So, trying to create disciplines for state-owned enterprises, and trying to make sure small and medium-sized businesses which are really the drivers of growth and the drivers of exports including in our country, have the ability to participate in the global economy and to export more of their products. We work across manufacturing goods, services, and we work very closely with Secretary Vilsack and USDA on the export of agricultural products, breaking down barriers to American agricultural products. And again, California, I think exports — it's $23B a year. It's an all-time high — an all-time high of U.S. agricultural exports. It's a key part of what's driving our economy here.

Our exports are driving about a third of our growth in this country right now. And the only way that we can keep up with that is to keep on opening markets, making sure we have a level playing field that we compete on, and then making sure that we enforce our trade rights and that's what we're doing.

Greg Dalton: Republicans and Democrats don't agree on much these days, but they do agree that they don't want to grant fast-track authority to the Obama administration on this trade deal. Three quarters of the House Democrats are opposed, including the leadership of George Miller — a lot them including 19 Democrats who voted for the Korea-U.S. Trade Pact. So, how are you going to get around that if Congress doesn't grant you fast track authority?

Michael Froman: Sure. What Trade Promotion Authority is, is the mechanism that every Congress since 1974 has given every president, since 1974, Republican and Democrat, and it's the mechanism by which Congress tells the president what to negotiate, what the negotiating objectives, are how to work with Congress during the negotiations, what the consultation procedure is, and then what the process is for approving or disapproving the agreement at the end of the day.

Right now there isn't a trade promotion authority bill out there on the table yet. We wouldn't support the old trade promotion authority from 2002, either, which is what that letter is about. We want to make sure the Trade Promotion Authority reflects not only our interests but our values — labor, environment, access to medicines, intellectual property rights, disciplines on state-owned enterprises. These are all things that are new since the last grant of Trade Promotion Authority and it's something that we're very much looking for to working with Congress to make sure it gets done.

Greg Dalton: Another concern is secrecy, that is being done in secret, that Congress is not informed that there's 600 or so corporations, entities that are — that can see the draft to this, that part of it was leaked on WikiLeaks recently. So, what can you say to the concerns about secrecy of the profit?

Michael Froman: Well, this is the most transparent trade negotiation that's ever been, which doesn't mean we can't always do better, by the way. And we're always looking for ways to see what we can do to do better.

So for example, we — before we table any proposal at the negotiation, we preview it with our congressional committees and with other committees, agriculture committee on agricultural issues, with ways and means and finance committee on all of the issues. We have had 1083 briefings on the Hill on TPP alone — 1083 briefings. We've met with scores of individual offices. So, I think there's actually been a bit of congressional input and congressional review of what it is we're doing. But we haven't stopped there and the one thing we knew we've done with TPP is we've actually organized that at every round of negotiations, we organize an event for stakeholders. And we've had hundreds of stakeholders come and we've given them the opportunity and structured a program so they can present not just to us, but to the negotiators from the other 11 countries as well so that all 12 countries are here in the input of our stakeholders.

You mentioned the 600 cleared advisers. Congress established these committees to represent a wide range of interests. There are a lot of interests from businesses there but also every single major labor union is represented. We have environmental groups, consumer groups, public health groups. So, we have a wide range of groups that are also part of this process, but we're not limited to listening to those groups. We take in meetings from all possible stakeholders, whether it's Internet rights groups or public health groups or generic companies. Whatever companies want to come in and see us, whatever interest groups want to come in and see us, we have a process for including their input into our negotiations.

Greg Dalton: I'd like to talk about the intersection of trade and agriculture. In 2010, Russia suspended exports — fourth largest grain exporter because of severe droughts and floods. In 2008, Secretary Vilsack, we had rationing of rice from Sam's Club and Costco in the United States partly because of floods — droughts in Australia. The IPCC — the international group of scientists have warned about the impact of climate on food production. Are we going to see more scarcity and volatility in international agricultural markets, as the weather gets weirder?

Tom Vilsack: Well, let me tell you. What we're trying to do at USDA is to prepare for our agricultural producers to be able to continue to maximize productivity. We're establishing a series of climate change hubs — regional hubs which will be aligned with universities and agriculture to sort of look at each region of the country and to determine what is being grown, how climate change will impact and affect the growth of that over the long haul.

We have a tendency in Washington, I think, to talk in terms of when you're in five-year cycles in agriculture, one year for budget, five years for farm bill, what we really need to be looking at 25, 30, 40, 50 years out. And these regional hubs will basically allow us to do that. They will allow us to identify specific opportunities for us to help producers mitigate the impact of adverse weather conditions. And we've just announced a drought resiliency effort as well where we'll be collaborating with federal agencies to talk a look at ways in which we can mitigate and minimize the damage of drought that's going to take place.

We have a global research alliance that we've aligned ourselves with 30 other countries and the United States, and we are basically coordinating research in livestock and crop production in rice to make sure that we are ahead of the game, if you will, in order to try to minimize the kind of volatility that can occur when shortages occur. I can't guarantee that we're not going to have shortages, but I can guarantee you that we are very focused on making sure that we are in a position to adapt and mitigate as best as possible.

Greg Dalton: 2012, there were some record droughts that really hit production. Is that connected to climate change? I know you're not a scientist but do the farmers connect that with the climate change?

Tom Vilsack: Well, I think the farmers recognize that they need to be prepared for any kind of weather condition. And that's one of the things about farming, is that there's just extraordinary risk associated with it. I mean, you can be the very best farmer in the world. You can do everything right in planting a crop. You can invest your hard-earned resources and livelihood, but the reality is if Mother Nature decides not to have a rain or it rained too much, it can wipe out your entire crop.

What's interesting about last year's drought was that despite the fact that it was the worst drought we had in 80 years, corn production was at a — within the top 10 corn crops in the country's history. And so, that's essentially working with technology, working with farmers and making them better able to deal with adverse weather conditions by the way in which they plant their crop, when they plant it, how they plant it, how they cultivate it and tend it. You can minimize an impact of a drought.

Greg Dalton: But we're not talking about Mother Nature anymore. We're talking about human tinkering of the climate system, right?

Tom Vilsack: The reality is — I know it really about understanding how we can use conservation techniques, for example, to maintain moisture. We're beginning to see a re-emergence and we're supporting this at USDA of cover crops. The opportunity for us to basically have multiple crops during the cropping year that will allow us to retain moisture and nutrients in the soil and make it a little bit more resilient, if you will. And we're doing the same thing in the forest area as well. We're trying to focus on resiliency and trying to equip our farmers with the latest and best information on how they can be more resilient to changing climate.

There's no question — we can debate what's causing it, but there's no question that it is changing. There's no question that we're dealing with warmer temperatures and that — and more intense storms and weather patterns. And so, we have got to be in a position to respond to that. We face a huge global challenge of increasing food production by 70 percent the next 40 years with less water, with more intense weather patterns. It is going to require a global commitment to research, to science, and to make sure that we are identifying best practices and making sure that information is shared and readily available. And we're trying to do that through USDA, through a variety of activities.

Greg Dalton: Ambassador Froman, how is climate disruption going to affect trade patterns and trade? Is that part of the discussion?

Michael Froman: Well, environmental issues generally are very much part of the discussion that the U.S. has, we've been trying to add environmental issues to the agenda. And for example, in the Trans-Pacific Partnership, where for the first time, trying to take on certain conservation issues that are specific to this region. Issues like illegal logging or overfishing and the subsidization of overfishing, or trafficking of wildlife, of endangered species and other wildlife — and trying to use the TPP as a mechanism for getting countries to cooperate together to try and put disciplines on those branches that are having and adverse effect on the environment.

So, we think that — again, our trade agreements ought to reflect both our interests and our values. And that's something the president has felt very strongly about, and that includes labor and the environment and public health.

Greg Dalton: In 2009, I believe it's your hometown, Pittsburgh, the group of G20 pledged to reduce fossil fuel subsidies. That was before the Copenhagen summit. I haven't heard much about that lately. Ambassador Froman, is that still a goal to reduce and liberalize fossil fuel subsidies in international trade?

Michael Froman: It is, and I used to be involved in the G20, so I'm delighted that you found that in your archives. Yes — so we've got global agreement for countries to try and do this. And it started with the G20, then the APEC countries around all of Asia Pacific also agreed to do it. You know, it's a long-term process because for a lot of these countries, it's very painful to start reducing the subsidies, raising energy prices and at least social unrest at times, and we've tried to work with countries through the World Bank and others to make sure they've got the social safety nets in place so that the people who most need the subsidies in a society, the poorest people, the most vulnerable people are still able to get the energy the need.

One of the tragedies about fossil fuel subsidies generally, not only that it leads to the overuse of fossil fuels, but a vast majority of the subsidies go to the people who don't need them. They go to companies or people who can afford to pay the full price of fossil fuel. So, if countries really want to take care of their poor with fossil fuel subsidies, there's plenty of room to do that while raising the prices and discouraging the overuse of fossil fuels.

And we're trying to use all these mechanisms like the G20, like APEC, and like other mechanisms like that to try and encourage countries to do that.

Greg Dalton: It's safe to say that no subsidies have been disbanded or diminished yet –

Michael Froman: You know, it's not safe to say that. There are a number of countries that have actually raised their prices on fuel. Take India, which has raised prices on diesel and a number of other fuels. It's happening in Russia now, which is one of the main subsidizers of fossil fuels. So, there are a lot of countries that, for their own reasons, whether it's fiscal, environmental, public health or otherwise, see the value in reducing the subsidies, raising the prices of fuel closer and closer to global market prices, and retargeting that money towards better purposes.

Greg Dalton: So, as fossil fuel prices raise, what does that mean for agriculture, trade, and trade in general? Because a lot of the whole trade is really premised on cheap fossil fuels. Secretary Vilsack, does it make sense for us, California, to export refrigerated raspberries and strawberries to Asia if fossil fuel prices increase.

Tom Vilsack: I think there are several responses to that. First of all, we are developing technologies that don't necessarily require quite as much energy as they use to, in terms of crop preservation and in terms of being able to transport crops overseas without using as much energy, number one. Number two, we are still looking at ways in which we can expand and diversify our energy portfolio so it is less reliant on fossil fuels. You know, you and I mentioned before the show started today that we're really focused on with energy, the ability to take the deceased wood that we have way too much of it in the western part of the United States, do a better job of removing that deceased wood and converting it into energy. It's going to burn. It's just a matter of whether it burns in a positive way or negative way. And so, that's where we're heavily involved in research projects. So, we're trying to make sure that we get those opportunities out.

We're obviously looking at ways in which we can make agriculture more efficient and I mentioned cover crops and that's one of the strategies, we're making agriculture more efficient.

And so, there are a multitude of ways to deal with this, and I — agricultural trade is very important to American farmers. We are a food-secure nation. We basically can produce everything we need to feed our people. But because we've become so efficient, we actually produce more than we need, and so we are providing it to the rest of the world. The Ambassador mentioned jobs. Agricultural trade supports about a million jobs at home and it helps stabilize farm prices so that we can keep people on the land and keep people populating those rural communities that are important to this country.

Greg Dalton: We're going to get to local and organic in a minute, but first, Ambassador Froman, the idea of will trade decrease as fossil fuel prices increase. Or will the price of trade go up? What changed the economics of trade, because there's all — the whole system is predicated on cheap subsidized as we just talked about fossil fuel?

Michael Froman: Well, there are subsidies that are applied in a number of areas. The biggest subsidies one sees in fuel are setting electricity prices at way below market prices in developing countries. That's where the bulk of the fossil fuel subsidies are, and that's where the progress I think is being made to raise those to make it a more rational or rational pricing system.

There are so many factors that go into trade including the cost of transportation. But there are also — our trade is also changing. It's agricultural products, it's manufacturing products, it's also services. It's also digital products. These are fast-growing areas, and I've spent the morning in Silicon Valley today. There are so many innovative products coming out of this state, out of this community that have the opportunity to make a major impact on global markets and obviously those of us who'd been issued in fossil fuels, that making sure they have access to markets and that governments aren't putting regulations in such a way as to keep out American products just because — even if they're digital.

Greg Dalton: Secretary Vilsack.

Tom Vilsack: Let me add to that. Because — it's not just a matter of trade. It is also a matter of making sure that agriculture around the world is sufficient as productive as can be. So, we have a feed-the-future initiative that we're working with the state department in USAID where we basically are trying to encourage more productivity on the part of farmers all over the world. We see the opportunity for developing countries to embrace agriculture, to become more productive. They can, in turn, can increase incomes for their people, middle classes grow, middle classes desire many of the products that we produce here in the United States, and they are then in a position to begin trading.

We see this, for example, in Afghanistan where we're trying to promote agriculture that will allow them to trade saffron, apricots, pomegranates to India and other countries, creating new income opportunities. And interestingly enough, farmers in Afghanistan, if they embrace those new products, they can actually make more money than if they produce poppy and opium.

Greg Dalton: There is a lot of food trade. There's also a trend these days toward local, slow, organic food. I'd like to get your thoughts both on sourcing locally if that's something you see growing, and also — yes, let's start there first.

Michael Froman: Well, in order for the rural economy to revitalize, we have to move beyond production in agriculture, in exports. We have to complement that system with additional systems. And one of the systems that we are investing in at USDA is the local and regional food system the ability to sell directly to a consumer. It allows smaller entrepreneurial activities to get in the game. It's pretty hard for them to compete in a commodity market but it's very easy for them to compete in a local — at the regional market.

So, we have a program to expand farmer's markets. In all there are 2840 more farmer's markets exist today than it did four years ago. We have the ability to encourage food hubs. This is an aggregation of locally and regionally sourced food so that you can sell it to institutional purchasers like schools and universities. We have 140 of those that we've helped, and that's tripled the number throughout the United States.

There are 107,000 farming operations that are currently involved in direct-to-consumer sales. It's one of the fastest growing aspects of agriculture. It's $45B in trade opportunities in economic activity and it supports jobs. So, we are very much involved in this we are now getting our schools — our high schools and our grade schools very much involved in this. In 35 states, we have a farm-to-school program working and we just recently did a survey and found that nearly 50 percent of American schools are very interested in being able to source locally.

So, as you create more of these local and regional food systems, you create job opportunities and small entrepreneurial activities in rural America and you help to rebuild that and complement production agriculture.

Greg Dalton: And is that providing higher quality food to schools? I read, like sugar-salt-fat they talk about schools as kind of a place to dump excess inventory of the –

Tom Vilsack: Those dates are much different today than it was a couple of years ago with the passage of the Healthy and Hungry-Free Kids Act. We at USDA have changed the guidelines and standards for school meals. So now we're in a position to encourage more fruits and vegetables, more whole grains and low-fat dairy, and less sodium, sugar and fat content in the meals. And we are continuing to purchase surplus products but they could be blueberries, they could be cherries, they could be oranges, and they have been in the last couple of years.

And so, we are improving the quality not just of the meals but also of what's being sold in vending machines, with our competitive food role. We're basically saying, look, we want you to complement this good, nutritious, wholesome food that we're serving with better snack opportunities and options as well as better à la carte options. So, you're seeing a significant change in the way in which youngsters at school would receive these meals and receive snacks.

Greg Dalton: First Lady has had a big impact on that as we know. You mentioned productivity. Are organic farms productive?

Tom Vilsack: Well, they are certainly productive and they are certainly high value-added.

Obviously, organic products sell for significantly more than basic commodities. We have about 17,500 certified organic operators in the United States today. They farm about one percent of America's farmland and they are responsible for about four to five percent of the sales. So, you can see at one percent of the land, three or four times in terms of total sale. So, it's a high value-added proposition. It's a proposition that we're trying to make sure can co-exist. I'm not going to be in a situation today or any day to choose between production methods. Our department is trying to foster co-existence, so we're asking the questions how do — does an organic producer and a GMO producer live in the same neighborhood, live in the same world, how do they get along, how do they make sure that they don't compromise each other's crops. And we're working on risk management tools, we're working on maintaining seed varieties, we're working on drift research, and we're creating a dialogue that has been missing in American agriculture for some time.

And frankly, American agriculture has to have that dialogue. It represents less than one percent of America's population and most people are several generations removed from the farm. And I think it's important for American agriculture to be relevant in terms of political relevance; it's going to be important for us to continue to communicate more effectively to the other 99 percent.

Greg Dalton: One more question and I get to Ambassador Froman. You mentioned not choosing among conventional or organic. Does USDA promote organic?

Tom Vilsack: Absolutely. We established for the first time in this administration its own separate division. We have substantially increased and focused on the standards and the brand of organic to make sure that it is strengthened, to make sure that it's preserved. We are investing significantly more in research; about $140M of research has gone into organic research. We are setting aside $50M of conservation resources for organic producers. We're expanding our conservation programs to encourage tollhouses which extend growing seasons for — especially crop producers, many of which are organic.

We are heavily engaged, as the Ambassador knows, in negotiating equivalence agreements with Canada, with the EU, and now Japan to allow our organic products to be sold overseas. It's going to create huge, new opportunity for organic producers. It's still a relatively small percentage but it is, again, a fast-growing aspect of food and agriculture in this country, and it helps to revitalize the rural economy. It's entrepreneurial, it's innovative, and I think it's a good complement along with conservation in the bio-based economy. We're trying to build a new rural economy.

Greg Dalton: And some people would argue that organics are more resilient because of the crop diversification rather than monoculture, et cetera. If you're just joining us, our guests today at Climate One at the Commonwealth Club is U.S. Secretary of Agriculture

Tom Vilsack, and U.S. Trade Representative Ambassador

Michael Froman.

Ambassador Froman, Secretary Vilsack mentioned GMOs. That's a point of trade contention with Asia. Some corn was just rejected by China today. Japan — Europe has different GMO labeling laws than the U.S. How is that going to play out in trade?

Michael Froman: Well, it's clearly a big issue in the trading world, and different countries will come to different conclusions about what kind of seeds, what kind of products they want in their country. Our position has always been that we encourage countries to develop regulations in accordance with science and to take whatever actions they feel are necessary to protect their health and safety, environment of their people, and to do so in a scientifically sound way. And that's the kind of dialogue that we're having with Europeans as well as other trading partners.

But people come through from a different perspective, and if we can have a scientific discussion about it, I think we have the possibility of moving forward together.

Greg Dalton: What's the U.S. position on at least labeling or disclosure? We had some laws — validation period that lost in California; there's been some others around the states, but does U.S. have a position on France and other places in terms of labeling of GMO products?

The philosophy of labeling in this country has always been basically on nutrition and basically warning of known hazards. And in that respect, it's difficult to make the case for labeling. However, there is a desire on a lot of folks to know what's in their food, and frankly I think the conversation that we're having in this country is a bit misplaced on this issue. I think we're talking about 20th century technologies in a 21st century world. What I have been suggesting and what we've started with discussions with the FDA is a process in using potentially QR codes as a way of basically establishing the opportunity for consumers to know but not to create it in a situation that might — that might suggest that there's something wrong with the product.

Greg Dalton: QR codes, we should expand on those little squiggly squares that you see on products that you can –

Tom Vilsack: And you can use your smartphone or you can have a scanner at a grocery store that will allow you then to actually have a great deal of information about the product so the consumers that want to know everything would be able to do that; consumers who aren't as interested wouldn't necessarily need to do it. But it's a way of, I think potentially establishing a process that bridges the gap between those who believe there's a right to know and those who believe that you don't want to send the wrong message about the safety of a particular food product.

Greg Dalton: Fracking is a big issue in the United States. Ambassador Froman, a few years ago it was thought that the United States would be importing natural gas. Now, it looks like we're going to be an exporter of natural gas. There are some LNG terminals that turn the pipes around to point the other direction. How is that going to — that's a fairly new thing. Natural gas is not traded like oil in the global market; how is that in terms of a trade issue, natural gas exports?

Michael Froman: Well, it's really more of an issue for our colleagues at the Department of Energy than it is for us at the U.S. Trade Representative's Office.

Department of Energy has the authority to decide whether to approve various licenses for people who want to export natural gas. There is a lot of interest in that and they are working through those licenses, taking into account all the various factors including the impact on the marketplace. The only real link to trade is that where we do have free trade agreements with countries that grant us national treatment, it's presumed to be in the national interest to allow exports. But that sort of gets sorted out largely I think by the markets and by a whole series of regulations, of our environmental regulations, FERC regulations, deregulations that anybody who wants to export natural gas will have to go through before they can do that.

Greg Dalton: Secretary Vilsack, a lot of fracking happens near agricultural lands. There's concerns about water supply contamination. How much time do you spend thinking about fracking?

Tom Vilsack: Well, I think a great deal of time. I spend a lot of time thinking about water and the availability of it and the quality of it. As Ambassador Froman suggests, that some other departments of government may have more of a specific vested interest in those decisions, but what we're trying to do at USDA is make sure that we provide our farmers and our producers and our land owners with the best available information on how best to utilize scarce water resources and how to conserve water resources. And we're also understanding and recognizing that as we maintain our force, that for far too long we have not looked at our force as the conservers and preservers of water that they are and doing a better job of restoring and making our forests more resilient while obviously increase the quantity of water and allow it to be available when it needs to be available.

And it also goes to the whole issue of infrastructure, which gets a little bit beyond my world, but I mentioned that we are — that Farm Bill is an infrastructure bill, and the reality is that we've invested in almost 3800 water projects throughout the United States as a result of the Farm Bill programs. So we've — we need to invest in more infrastructure and better infrastructure.

We need to better utilize the water resources we have. We have to make our land and our forests more resilient. And that requires us to continue to invest in the science and continue to invest in conservation practices. Cover crops are a good example. And with precision agriculture, I think we're getting to a point where we might be better at this than we've been. We'll let the folks in EPA and the Department of Energy talk about the regulations of fracking, but we're going to be focused on making sure that we know how to use water resources effectively, not just here but also internationally as well.

Greg Dalton: And you mentioned the importance of forests to water. Some logging interests would like to have more logging on federal lands. Is that something that you're going to let happen?

Tom Vilsack: Well, we established new forest planning role, the first forest-planning role since 1982. In it, we reflect the multiple purposes to which forests can and should be utilized. Part of it is the timber industry, obviously. Part of it is the energy industry. But also part of it is recreation. Outdoor recreation's a huge financial mover in rural communities. It's a $650B-plus industry, and we obviously need to make sure that our forests are good places for people to recreate, because those recreation dollars help to revitalize the rural economy. I think it's also important that we — that we focus on old growth, that we maintain the old growth, and that requires us to take a look at stewardship contracting, take a look at how we better maintain our forests through this new forest planning role and management decisions that we've made.

We've got 155 forests in this country, 193 million acres of forests and grassland areas which we are very seriously looking at, and you will probably see more board feet treated but you'll see it treated in an environmentally appropriate and focused way. We're going to continue to look at ways in which we can expand important and critical habitat and areas where wilderness designations and so forth need to be protected.

But we also I think need to recognize that these rural communities that are — I visited Trinity County in California — 75 percent of that county is in forested land. They were obviously concerned about the lack of economic opportunity coming from that forest, and we're now in the process of trying to figure out ways in which we can create new opportunities that didn't exist or to expand opportunities but to do it in an environmentally appropriate way.

Greg Dalton: I don't know if you knew Dave Freudenthal, former governor of Wyoming, once and he said that people in Wyoming would dismiss climate change but they would come in and talk about the pine bark beetle all day long. While the pine bark beetle has devastated forests from the Rocky Mountains up in the British Columbia, it is connected to climate change because the warming temperatures, the beetle's larvae do not die in the winter, so how will climate affect America's forests?

Tom Vilsack: Well, it continues to put a premium on making sure that we make them more resilient and that we restore them properly. You mentioned the pine bark beetle, and obviously we've invested nearly $300M in the western states to try to begin the process of removing some that wood so that we reduce the fire hazard because it obviously is pretty significant. And I think there's an opportunity here for us to link that need with a new opportunity for what I refer to as distributed generation of power, basically localizing our power production by using that woody biomass to produce heat and energy, perhaps linking it with colleges and universities and public entities to use that wood in a more effective way from an environmental standpoint, and do a better job of maintaining those forests.

Greg Dalton: Tom Vilsack is U.S. Secretary of Agriculture; he's our guest today with Ambassador

Michael Froman at the Commonwealth Club. I'm Greg Dalton.

Meat and dairy are a big part of the carbon equation. Some people say one of the best ways to fight climate change is eat less meat. How does that sit with the USDA, which is largely promoting meat and dairy?

Michael Froman: Well, we're promoting it as agricultural opportunity. And here's why.

And I think everybody has to recognize that we all have a stake in the survival and health of rural America. It's a place where most of our foods is produced. It's a good place where most of the service water is impacted. It's the source of most of the energy feedstock as we've mentioned. It's a place where we all go to recreate, but it's also a place where 16 percent of America's population helps to produce nearly 40 percent of America's military. So, a lot of the sons and daughters that grew up in the small towns and all those farms and ranches are willing to sacrifice for their country. And I think it's partly a value system that they grew up, being exposed to in those rural areas.

So, you need economic opportunity. For the first time in our history, rural America lost population. It is the place where 85 percent of persistently poor counties happen to be. It's not — the poverty is not limited to inner city. It's also very much in rural areas. So, you got to create economic opportunity. And so, you want a livestock industry because that's the way in which traditionally we've added value to the crops that we grow. But that is not by itself enough. We — as I've said earlier, we've got a complement production agriculture with local and regional food systems which can include livestock and often does. We've got to complement with outdoor recreation and new ecosystem markets and proper use of conservation resources, which we're trying to do and we have to create this bio-based economy.

I think it's a balance. I think it's a combination. It's not just one solution. It's a diversification for agriculture, it's all sizes of operations of agriculture, and it's different uses of agricultural products. And the reality is that one of the reasons why we've had record exports is because the rest of the world is very interested in purchasing a lot of the beef and the pork and the poultry that we produce in the United States; it's not necessarily being Americans that are consuming these.

Greg Dalton: Ambassador Froman, the Electronic Freedom Foundation said that the Trans-Pacific Partnership puts at risk some of the most fundamental rights that enable access to knowledge. And I think there's concern that the Trans-Pacific Partnership could be an attempt to revive some of the online patent of protection acts that were unsuccessful with the SOPA, the Stop Online Privacy Act that Google and this big uprising last year. So, address those concerns.

Michael Froman: Yes, I'm glad you raised that because I've seen those reports and I think they are really close to 100 percent wrong. What we're trying to do through TPP is actually create greater openness in the digital economy, allow for free flow of data, encourage countries to ensure that people can get access to the internet, that they can get access to cross-border services, that their businesses can use cloud computing, as some of the latest developments in that area, that they don't impose certain walls around the internet, that they don't use that as an excuse for censorship.

So it's exactly — what we're trying to do is to make sure that it's open. Now, we are — we do believe in supporting certain intellectual property rights. But we do that very much in the context of the balance that's already been struck in U.S. law. Now for example, in U.S. law we have exceptions and limitations to copyright for various uses. And this is the first trade agreement where we will be putting forward exceptions and limitations, and encouraging other countries to adopt laws that allow for exceptions and limitations on copyright law.

So, it's a balanced approach that reflects the U.S. law and at the same time when it comes to new technologies in the digital economy, we're working to make sure that this is as open as possible.

Greg Dalton: Then why is a group like EFF so concerned if it's really as open? I mean it's hard to reconcile both of those.

Michael Froman: Well, I think one of the challenges we have here is there is no agreement yet for anybody to focus on. So, all we can talk about is what we propose. And people are naturally concerned until they see the final result to make sure that we're fighting for their rights and fighting for their interest. We're doing that, and we're talking to all sorts of different stakeholders on all of these issues. All the times the stakeholders have competing and conflicting interests, but our job is to try and find a balanced approach and then negotiate an agreement with the 11 other countries that reflects the best interests of the U.S.

Once the agreement's done and people can see what's actually been agreed to — one of the challenging things about a trade agreement is that nothing's agreed to until everything's agreed to. And usually nothing's agreed to till about 3AM in the morning on the last day of the negotiation. So, once it's all done then we can show people exactly of all the balances that have been struck, I think people will be able to see that we've done the right thing including on those issues.

Greg Dalton: Another concern is medications. One group, Public Citizen wrote that the deal will strengthen, lengthen and broaden pharmaceutical monopolies on cancer, heart disease and other drugs in Asia Pacific.

Michael Froman: Congress, back in 2007, reached a bipartisan compromise on a series of trade issues. They told us what to do on labor, what to do on environment and what do on intellectual property rights including pharmaceuticals. And they give us direction that there should be a distinction made between countries at lower levels of development to ensure that there could be access to medicines by the poor, and countries at higher levels of development who have higher levels of intellectual property rights protection.

And it's that kind of approach that we are pursuing through the Trans-Pacific Partnership. We want to make sure that there's access to medicines, the generics can get into the market particularly in developing countries as soon as possible at the same time as we are encouraging innovation in our country, and the kinds of innovation that then lead to generic drugs as well.

Greg Dalton: I'd like to ask both of you to comment on this and we're going to audience questions in a minute. The New York Times reported earlier this year on, I think it was titled "America's Wage Pickle." The productivity of American workers has increased dramatically in recent years, and yet wages have been stagnant. So, Caterpillar — it was this one example recorded record profits but they had a six-year wage freeze on blue-collar workers. They're kind of an icon of rural America. So, I'd like you both talk to rising productivity but stagnant wages what some people connect with trade deals. First, Ambassador Froman.

Michael Froman: Well, I think this is a serious issue more generally about the need to ensure that there are increased wages and that the benefits of trade are broadly shared. You know, export-related jobs tend to get paid 13-18 percent more on average than non-export-related jobs. And so, increasing exports and encouraging and having more people in the sector that are taking advantage of these open markets abroad is one way of encouraging higher wage growth.

But it's one of the reasons also through our trade agreements that we're trying to level the playing field by raising labor standards in other countries as well so that our workers don't face an unfair situation of having to compete against workers who don't have to live by similar aisle of standards.

Greg Dalton: Secretary Vilsack?

Tom Vilsack: The biggest concern I had on wages is the disparity between rural wages and the rest of the country. Median family income in rural areas is about $22,000 less than it is in other parts of the country and that basically explains in part why we have the highest poverty rate we've had in 25 years, and why we continue that persistent poverty in many rural counties. It's one of the reasons why we created the thing called Strike Force where we're really focusing with intensive care and direction on these high-poverty areas, to try to increase economic activity.

We need to rebuild the rural county and we need to basically bring manufacturing back. And one way you do that with the Farm Bill and the programs that a farm bill could support is creating these new manufacturing opportunities where you can take agricultural waste product and produce something more valuable. This is about taking corncobs and producing plastic that Coca-Cola uses for their plastic bottles. So, it's about taking switchgrass and converting it into a material that substitutes for fiberglass that's stronger but lighter, that will allow for more fuel-efficient vehicles. It's about taking literally hog manure and producing asphalt from it that would help reduce the cost of paving road, believe it or not. That's actually happening in Ohio right now.

When you think about the opportunities to take everything we grow, everything we raise, and replicate nature by creating something more valuable and having no waste, if you will, it's a tremendous opportunity to bring manufacturing back. And when you do that, you can help complement production agriculture and some of the local and regional food systems we've talked about earlier.

Greg Dalton: There is no waste in nature — yes, people who read Bill McDonough or involved in biomimicry. We're going to include our audience questions. I can see you know the line. We got — I'm not sure we'll get through all of them. I want to encourage you to keep your questions concise and brief. I will get through as many as possible and if you need some help keeping it brief, then I will be happy to help you keep it on point and brief. Let's include our audience questions. Welcome to Climate One.

Peter Gisela: Hi. Peter Gisela. Four sentences. Secretary Vilsack, on July 15th, President Obama issued a memorandum to the heads of executive departments and agencies on the subject of creating a task force on expanding national service through partnerships to advance government priorities. USDA is a member of this task force. My question: Could you provide me the means to contact your representative and encourage this task force to create a website transparency for input from non-government institutions for a more effective, systemic changes in partnerships? And I hope Ambassador Froman could also encourage the White House towards these requests.

Tom Vilsack: Matt Paul is my communications director. He happens to be in the facility, in the building today. He will give you his card and you can contact him immediately. Actually, you can talk to him right now.

Greg Dalton: Let's have our next question for U.S. Secretary of Agriculture

Tom Vilsack and Trade Representative Ambassador

Michael Froman.

Pat Tibbs: Mr. Ambassador, I'm Pat Tibbs. I'm a San Francisco resident. Can you assure us or will you assure us today that you will not sacrifice net neutrality in developing the TPP?

Greg Dalton: You might explain that neutrality. I think that's the point in there.

Michael Froman: Well, yes. Let me — I believe I can say yes. But I want to make sure I'm answering the question the right way. What we're seeking is to ensure that there are no undue regulations of the Internet, and so that's consistent with net neutrality. And there's nothing in TPP that would run against that. So, assuming we're successful in our negotiation and we're able to get 11 other countries to agree to our principles about the digital economy and we're able to get that agreement through Congress, then I can assure you that.

Greg Dalton: Let me just follow up by saying, there's actually an ICANN meeting now in Brazil which is the governing body for the Internet, and there's a perception there that some countries are trying to exert more influence over internet governance.

Michael Froman: I think that's absolutely right and that's something we should all be quite concerned about. And one thing again, just to go to the questioner's point, one thing we're trying to do through TPP is exactly counter that by saying that the Internet ought to be open, it ought to be free, that there shouldn't be interference in Internet governance. But that requires us to actually be able to get the agreement done and get it through and get it through Congress as well.

Greg Dalton: Let's have our next question. Welcome to Climate One.

Female Participant: Secretary Vilsack, I live in East Bay and George Miller is my congressman. You mentioned water conservation and cover crops, but I didn't hear you say anything about recycled water. Whenever I talk to George Miller about this, he says there are no federal dollars for recycled water. Yet, Alameda and Contra Costa County throw as much as a billion gallons of recycled water into the bay in one day and it can be tertiary grade, used for agriculture. So, why isn't there more money coming from the USDA for use of recycled water in agriculture?

Tom Vilsack: Well, I'm not sure that that's not happening. I think there are projects that we're helping to fund in using water more efficiently and more effectively and recycling water. There are a wide variety of ways of which the USDA are focused on renewable sources, so I'm not sure that's correct.

Having said that, we are — we have a National Institute of Food and Agriculture which is a competitive grant process, and we are focusing these competitive grants with universities, land-grant universities on a couple of key areas, and one of those areas is on climate change and one of it — one of those areas is on renewable resources. And so, to the extent that we can get universities engaged in this as well, there's another opportunity for us to expand on the conservation monies that are being spent in this area.

Greg Dalton: Let's have our next question for Secretary Vilsack and Ambassador Froman.

Female Participant: Thank you. I have actually two questions; I'll be brief.

Greg Dalton: You can have one question. Can you step closer please?

Female Participant: Could you — could the Secretary of Agriculture please comment with regard to the QR codes. It seems to me that people aren't owning smartphones would be prevented from the knowledge of what's contained, for example, in products, if I understood your comment on that.

Tom Vilsack: Sure. And that's why I think it would be helpful and probably appropriate for the grocers to basically have available scanners that could be used by those who don't have smart phones. I mean, the point of this is not to prevent somebody from getting information. The point of it is to get information to folks in a way that is not judgmental, which I think a lot of folks on the other side of this issue have concerns about. So, it wouldn't be denying people access. The technology would be available, whether it was your own phone or some kind of scanning material at the grocery store.

Greg Dalton: Let's have our next question. Welcome to Climate One.

Jim Dorncut: Thank you. Jim Dorncut, Vietnam veteran, and I have to say, you know, as a veteran who risks his life for democracy, I'm very concerned about the lack of public accountability in terms of decisions that are made in these investor-state course. I mean it seems to me that that is the opposite of what democracy should be where courts made up of corporate people can decide whether our environmental laws that we decide democratically to enact, protect our people, can be overridden by these courts. And that we have no appeal process.

Greg Dalton: Thank you –

Jim Dorncut: This seems to me something that makes this unacceptable.

Greg Dalton: Ambassador Froman?

Michael Froman: Well, first of all, thank you for your service. Let me answer that question directly because there's nothing in TPP and nothing in the investor state that actually requires a government to undo a regulation that it thinks is appropriate. There are a number of ways of dealing with that. Now, we've never lost an investor state dispute settlement challenge in the United States. And that's because our regulations go through a fair and transparent and non-discriminatory process. Our regulatory agencies don't adopt regulations in order to discriminate against foreigners. But that's not true so much around the world. There are lots of places around the world where American firms and American workers are being adversely affected because a government will adopt a regulation not because of his illegitimate public health or safety or environmental reason but as a disguised barrier to trade, and that's what investor state is really all about. It's one reason we've never lost a case in this country, it's another reason why it's been an important protection for American firms to be able to use it in other — not just American firms but from one developing country to another developing country to use it in other context.

Greg Dalton: Let's have our next audience question. Welcome.

Ellen Shaffer: Thank you. Ellen Shaffer, co-director at the Center for Policy Analysis on Trade and Health, CPATH. The U.S. actually has lost non-investor state case but a WTO case challenging our tobacco control regulations. So they're trying to prevent use of the addictive clove cigarettes in the U.S. Tobacco use is the leading preventable cause of death in the U.S. and the world today, killing 1200 Americans a day. We have worked with elected officials, tobacco control groups, public health groups and medical groups all over the U.S. who are beseeching the U.S. to support Malaysia's position that we carve out these tobacco control regulations and tobacco completely from the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Trans-Atlantic Partnership.

The U.S. — your office, instead of strengthening our original proposal to try to deal with this question, has now come up with a proposal that's been termed by main state legislators as completely without legal significance. What will it take for the U.S. to lead on tobacco control and –

Michael Froman: Well, in fact, we are leading on tobacco control. And I'm very glad you asked that question, because we're the first country that's put forward tobacco into a trade agreement. We're the first one to table a proposal on this; it's the first agreement that will ever — that has ever mentioned tobacco specifically as a product precisely for the reasons that you've said. We've put out a proposal. We got a lot of feedback including from tobacco control advocates who are concerned about elements of our proposal and we've been evolving that proposal ever since.

And we're continuing to work that in the negotiation. It's one of the topics that's currently being negotiated in negotiation and we're working with Malaysia and other countries to ensure that we come out with something that's appropriate on exactly the issue that you said, while at the same time doesn't create a precedent that could be used for other agricultural products or other products that are not intended to be covered by it.

Greg Dalton: Let me just unpack that a little bit. It's the concern that if a city or state makes rules about tobacco, that some other country can challenge those under free trade rules. Is that it?

Michael Froman: Well, I think the concern is that we want to make sure that what the FDA or its counterparts in other countries, or as you say, at the state or local level, have the authority to adopt antismoking or tobacco control measures that are consistent with public health objectives. That's what we want to make sure that they have and that's what we're trying to do through this agreement.

Greg Dalton: Ambassador

Michael Froman is the U.S. Trade Representative. Let's have our next question at the Commonwealth Club.

Joe Brenner: Joe Brenner, Center for Policy Analysis in Trade and Health. The question for Ambassador Froman, related question. San Francisco and California have taken effective action to protect public health and to reduce tobacco-related disease and death.

When California attempted to ban the carcinogen MTBE seven years ago from gasoline, the Canadian company filed a trade challenge against the United States, suing the United States for millions of dollars under the investor state provisions of NAFTA at a tremendous cost of time and resources of the United States and had a chilling effect, stopping other states from taking MTBE out across the country. The United States is proposing the same investor state rights to corporations, which would then give them the right to challenge local tobacco control measures. Why?

Michael Froman: Well, actually that's not true, I'm afraid. Again, this whole — once the agreement is out, you'll hopefully be able to see it. But we've added a number of safeguards to our investor state dispute settlement proposal precisely to deal with the kind of problems you have including safeguards where attorney's fees are reimbursed, where there's expedited treatment of dispute settlement, where the states can come together and direct the arbitrary tribunal of how to come out, and where — to you previous question is pouring, where we can deal with tobacco's specific elements of it in a way that's never been dealt with before. That case you've mentioned of course is the one that we've won. We didn't lose because we've never lost in investor state dispute settlement case.

So, we've never lost a case but we're adding safeguards anyway to ensure that our health and environmental authorities can adopt whatever regulations they think is appropriate consistent with science to deal with their issues.

Greg Dalton: Let's have our next question at the Commonwealth Club.

Judith Finch: Yes, I'm Judith Finch, and I'm a constituent of George Miller, and I'd like to address this question particularly to Ambassador Froman. I'm very concerned and I would like you to address — I know you've talked about many stakeholders in that, but it's been my understanding that most of them have been corporate stakeholders. And I particularly like you to address the idea of the fast track, something that was introduced originally by, I think, President Nixon. And I understand by this that the Congress will only have, after a bill is introduced, who have 90 days which would probably not be enough time for hearings, and how — more of the people.

We can't really communicate with our congress people if we don't know more about it. I've seen very little about it in the mainstream press indicating about that.

Greg Dalton: Thank you.

Michael Froman: Once that trade agreement is completed and it's immediately published, published within usually weeks of when it is completed, it will sit out there for months if or Congress on it. But the Trade Authority Promotion Authority process does is say, once it's formally introduced to Congress, there is a period of time and as a process including hearings, and there'd been hearings on very trade agreement and there's plenty of time for both the public stakeholder groups, from nonprofit organizations to others, and of course members of Congress to opine on it.

I should say by the way, every member of Congress has access to the negotiating text. We view the member of Congress as the people's representatives, and any member of Congress who wants to see the negotiating text can see it. We go up, we show it to them, we walk them through it, we answer questions, we devote staff to make sure that if they have any follow-up questions that we can answer for them, and we work with them before we table any text. There are relevant committees of jurisdiction to make sure we've got their input as well. So, we welcome a robust, open debate about this. We've been more open in terms of having more stakeholder events, a broader range of stakeholders, not just our current advisers which do, by the way, include environmental groups, labor unions, public health groups and others, but a wider range of stakeholders participate in all of our rounds.

Greg Dalton: We're talking about trade and agriculture at the Commonwealth Club. Let's have our next question. Welcome.

Female Participant: Hi. I have questions for both of you. First of all, why is food that is too radioactive to allowed for sale in Fukushima, Japan sold in the U.S.A? And the scientifically based position on GMOs is that they are known health hazard so informed people no longer feed their families corn, soy, canola or cottonseed ingredients unless they are organic. Nor bovine growth hormone nor aspartame poison.

So, I want to ask you, do you feed your families those poisons or are you in denial about them?

Greg Dalton: Okay, Secretary Vilsack? The way to get you in the game here, there you go.

Tom Vilsack: Yeah, no question about that. Obviously there is a disagreement with the questioner. Honestly I don't think that there are scientific studies. I've seen a portfolio of 660 studies that have looked at this issue of known hazards and safety with GMOs. There's no reputable study that I have seen that suggest that there's a health hazard. My family does consume them, I consume them, I'm still here. And I will also say that the world is faced with a fairly serious set of challenges in terms of feeding the global population. And if we do not embrace science and if we don't understand the importance of science in agriculture would be extremely difficult for us to meet that challenge.

So, as far as food is concerned, I would just simply say that food that comes in the United States has to meet the same safety standards as we set for food that's processed in the United States, and I am unaware of the fact that there are hazardous foods coming into this country from Japan. I'm happy to check that out. That's an FDA issue, Food and Drug Administration basically is responsible for inspecting those if it's fish, inspecting fish. We inspect meat, poultry and processed eggs at USDA, but I'm happy to check that out. But I know that we have an equivalency agreement and requirement at USDA. Nothing comes in meat, poultry or processed eggs unless it's equivalent for the safety standards in the United States.

Greg Dalton: On GMOs, quick food note, some people would say that it's difficult to do studies, that a lot of those studies that have been done, that have been industry-funded, some researchers say it's difficulty to get access to do those studies.

Tom Vilsack: Well, you could find 150 million reasons to have a discussion about scientific studies, but the reality is I've not seen a reputable scientific study that suggests and indicates what the particular hazard is. That's number one. Number two, what we do know is that we are faced with a serious challenge that unless we figure out how to grow more with less, how we figure out how to use less water, how we figure out how to grow food with these changing weather patterns that we talked about earlier, then we're going to confront a major problem in humankind.

We've got to increase food production by 70 percent in the next four years. That's the equivalent of the same amount of technology and advancement in agriculture in 40 years as we've had in the preceding 10,000 years. So, that's why we're encouraging investment of research. That's why we want the Farm Bill to pass so that we have additional opportunities to leverage research dollars so that we can continue to meet this challenge and have America be at the forefront, and doing it in a safe and sustainable way.

Greg Dalton: And climate change will — we need those drought-resistant crops. Let's have our next audience question.

Damian Luzzo: Yeah, my name is Damian Luzzo. I just — I guess, you know, maybe we haven't lost a specific case if an outside company has come in to the United States and say, why like that. I don't know a lot of where they're actually coming in and trying to do a lot of things here where we're actually having that much of a problem, but when we're actually going in there, such as Texas-based oil and gas company going in and suing the entire nation of Canada for $250M because they happen to pass a fracking moratorium, it kind of begs the question like, we're already having these talks with Chinese officials. They've been struggling to do fracking there. They're going to be coming here to do fracking in California. One would imagine with this kind of trade agreement. So –

Greg Dalton: So, let's wrap up there…

Damian Luzzo: What are we going to do with — yeah. I guess my main question is why doesn't the actual public, the people — the sovereign people of this nation have a say in this trade agreement?

Greg Dalton: Ambassador Froman.

Michael Froman: Well, obviously they do. And they do both directly and through their members of Congress. And I start from the premise that regulations — and no country — and we want to make sure countries, whether it's the FDA or whether it's USDA or others can adopt the regulations that they think are appropriate as their democratic representatives, that they would be appropriate for health, safety, and the environmental protection of our country and no trade agreement is going to undermine that. And that's our fundamental premise.

Now, we want to make sure that those are the same kind of premises that are followed around the world, and that people are engaging in regulation in a way that addresses their legitimate public health and safety and environmental protection and does so based science, based on evidence, and does so not as a disguise barrier to trade. And I wish every country had exactly the same regulatory system that we did where we have comments and participation by our public. Our people can make public comments where the regulatory agencies have to justify their regulations based on evidence and science. But it doesn't currently exist. We're working with other countries to help strengthen their capacity to do regulation as well.

From us, we're trying to use trade policy as a way of raising standards overall — labor, environment, access to medicines, intellectual property rights. Those are core principles for us as we engage in these negotiations. And that's what we're trying to do. I will not speak nearly as eloquently as Secretary Vilsack about what motivates him, but when I travel around the country and see people who are being put to work, hiring additional people, raising wages because we've managed to open a market for them or ensure that there's a level playing field to make sure that there's no obstacles to their exports and the fruit of their labor that they're getting — the fruits of their labor, to me that's what this is all about.

And when I travel in Africa — and I spent a fair amount of time working on African development, and see how impassioned African leaders and African up and coming entrepreneurs are about the role that trade can play in their development, I want to make sure that markets are open so that we have some chance of using trade and investment as important tools for development here at home and around the world.

Greg Dalton: I want to end by asking you a question I ask a lot of people who sit on the stage here with me: what are you doing to manage your own personal carbon footprint. Secretary Vilsack?

Tom Vilsack: We just purchased a home and we're in the process of making that far more energy-efficient. We are focused at USDA on significantly increasing the efficiency of our buildings. We have a major initiative at USDA to try to make us far more energy-efficient and to use less energy, and we actually have a monthly reporting process on how that's going. So, there are a lot of different ways and obviously, we're very much interested and invested in creating tools for farmers, in particular to know how best to use conservation to reduce their carbon footprint. We just launched a thing called "Comment Farm" which allows people to actually take a look at conservation practices and quantify the result of these conservation practices in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, and we believe that we can create ecosystem markets where people will invest in conservation in order to meet a regulatory responsibility they may have in the industry if they're able to measure and verify and quantify a conservation result. So there's a lot of activity both personally and professionally.

Greg Dalton: Ambassador Froman.

Michael Froman: Well, I was at — I would stand from the personal, which is we moved to a place so that my son could walk to school and we could get rid of the car and reduce our carbon footprint accordingly.

Greg Dalton: Our thanks to U.S. Secretary of Agriculture

Tom Vilsack and

Michael Froman, U.S. Trade Representative. I'm Greg Dalton. Thank you for joining us with free podcast of this. And other Climate One programs are available in the iTunes Store. Thank you for coming today at Climate One at the Commonwealth Club.

[Applause]

[END]