Digging Deep into the Next Farm Bill

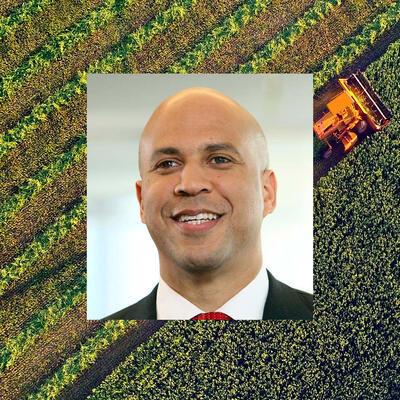

Guests

Jonathan Coppess

John W. Boyd, Jr.

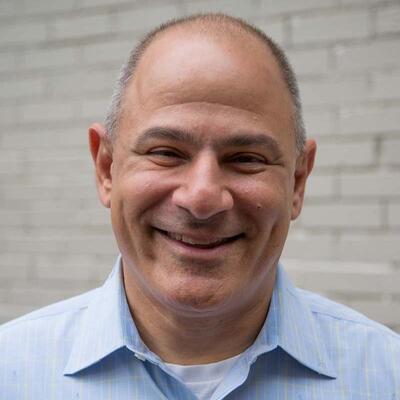

Chuck Conner

Scott Faber

Summary

Roughly every five years, the U.S. designs and implements a new farm bill, which sets federal policy on agriculture across a huge swath of programs, including subsidies, food assistance, land practices and more. As the discussion around what to include in the 2023 farm bill intensifies, many are pushing for climate mitigation and adaptation measures to be a primary focus of the legislation. These measures would include support for more environmentally-friendly practices like cover cropping — planting crops to cover the soil and not meant for harvesting — no-till farming to reduce carbon emissions, as well as agroforestry or planting trees near crops to help boost yields and sequester carbon. In February of this year, USDA Secretary Tom Vilsack announced $1 billion in funding for climate-smart agriculture pilot projects that claim to reduce emissions and sequester carbon.

Jonathan Coppess, Assistant Professor at the University of Illinois and a farm bill historian, says the crop insurance program, a significant part of the farm bill, becomes increasingly complicated when a widespread drought can wipe out an entire region:

“Where we’re gonna see climate change really the most concerns could be around the crop insurance program, because we are trying to run an insurance program that covers losses and as climate change drives more and more losses…”

Scott Faber, Senior Vice President of Government Affairs at the Environmental Working Group, argues both for safety nets for farmers and for limits on how much support wealthy farmers should receive, “ I think everyone agrees that we need a farm safety net. We need ways to help farmers weathers the ups and downs of agriculture, especially now that extreme weather is impacting farmers livelihoods. And I think also it’s the case that most farmers agree that there ought to be reasonable limits on who receives those payments and how much they receive. If you’re very, very successful you probably reach a point where you no longer need the government support.”

Chuck Conner, President and CEO of the National Council of Farmer Cooperatives, feels there is a chance to address climate issues that didn’t exist in the past, “I think there's a sentiment out there that this can be win-win. We can be pro-climate, we can be pro-farmer, pro-farm income and we weren’t there 10 years ago.”

Historically, the USDA has denied loans and subsidies for nonwhite farmers. John Boyd, president of the National Black Farmers Association, shares his personal experience trying to get a loan from the USDA:

“Trying to get a farm operating loan was just an uphill battle. This person spat on me during a loan exchange, called me racial epithets, tore my application up and tossed it in the trashcan. And when I was finally able to get someone to look into it they asked that man, ‘did you have any problems do you have any problems making loans to black farmers?’ And he said, ‘well yes, I think they’re lazy and look for a paycheck on Friday. But it doesn't have anything do with me doing my job.’ And this person after he was found guilty of discriminating against me and many others in Mecklenburg County, Virginia, he was still allowed to keep his job and moved to another county where he was allowed to retire. And that’s the whole thing with discrimination in USDA. No one was ever penalized or held accountable for the active discrimination.”

This episode is supported in part by Bank of the West.

Resources From This Episode (4)

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. How realistic is it to expect climate policy to be part of the next Farm Bill?

Jonathan Coppess: We have done big and difficult things in this country. But it is difficult. And our current political state I think you'd have to be blind to not just acknowledge that it's not getting any easier.

Greg Dalton: Since the 1930s, the Federal Government has supported farmers with subsidies, credit, and crop insurance, but historically Black, Indigenous, and other farmers of color have been excluded from these benefits.

John Boyd: We got to find a way around that circus, and circle, to really put some real hard programs into effect so that farmers of color can start receiving some benefits.

Greg Dalton: Can we make progress on equity and climate now that we couldn’t in the past?

Chuck Conner: This can be win-win. We can be pro-climate, we can be pro-farmer, pro-farm income and we weren’t there 10 years ago.

Greg Dalton: Digging Deep into the Next Farm Bill. Up ahead on Climate One.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. Roughly every five years, the U.S. designs and implements a new farm bill, which sets federal policy on agriculture across a huge swath of programs, including subsidies, food assistance, land practices and more. As the discussion around what to include in the 2023 farm bill intensifies, many are pushing for climate mitigation and adaptation measures to be the primary focus of the legislation. These measures would include support for more environmentally-friendly practices like cover cropping — planting crops to cover the soil and not meant for harvesting — no-till farming to reduce carbon emissions, as well as agroforestry or planting trees near crops to help boost yields and sequester carbon. In February of this year, USDA Secretary Tom Vilsack announced $1 billion in funding for climate-smart agriculture pilot projects that claim to reduce emissions and sequester carbon. Today we’re exploring what the farm bill can do to further incentivize carbon management practices while helping farmers and ranchers adapt to the increasingly disruptive impacts of climate change. This episode is supported in part by Bank of the West. Jonathan Coppess is an Assistant Professor at the University of Illinois and a Farm Bill historian. Climate One’s Ariana Brocious asked him where he sees the clearest avenues for incorporating more climate policy into the next Farm Bill.

Jonathan Coppess: It is a very complex and certainly an omnibus legislative vehicle. When we think about bringing climate change into federal agricultural policy, probably the first and most direct route is through what we call the conservation programs. So, these are a series of different types of assistance that we make directly to the farmer to do things like conserve natural resources, you know, to protect against soil erosion or improve water quality maybe reduce the amount of water they use in irrigation systems all the way up to things that might help protect habitat and some of the wildlife benefits we might see out of, say, retiring acreage for a set of time or rebuilding a wetland or things like that.

Ariana Brocious: So, within those conservation programs as you mention, there's a lot of them. And even farmers who take advantage of these, it might be a pretty small percentage of their overall acreage that's actually enrolled. How much room is there to grow them or put more money in them or encourage more farmers to actually take advantage of them?

Jonathan Coppess: The tough reality with conservation programs is that they're oversubscribed. So, they have pretty vast reach. I mean there's no sort of regional or statewide or crop-based limits on this. Any farmer, any farm landowner can conceivably enroll in a conservation program. Different ones have different priorities or things they try to accomplish. Like and the difference when you say a wetlands program that tries to restore wetlands and something like the environmental quality incentives program, which pays farmers a cost to share sort of offset the cost of say putting in a grass waterway, or if it's a livestock operation to address handling the manure and storage and sort of cleaning up things like that. So, they can apply very broadly. I think our biggest problem is funding. In fact, the biggest challenge for a Farm Bill debate will be the politics around the budget. And the fact that these are kind of stuck if you will, into kind of a fit box or a fixed boxed of funding. So, there’s not a lot of additional money to move out. And so, if you’re gonna increase demand or increase usage of these dollars we’re just spreading the same amount of dollars over more and more efforts, in that case more acres, more farmers.

Ariana Brocious: So, if we were trying to encourage something that we know has climate benefits like no-till agriculture where you’re helping not release carbon emissions. Is it just about getting more funding to kind of go with the existing programs and really make those more widespread?

Jonathan Coppess: In the conservation title, yes. I mean most of that is gonna be around how do we expand the funding for you know pick your acronym, pick your program and try to get more acres more farmers enrolled but to do that you need more money? When we think about getting climate change or practices that help address climate change. So, things that may capture greenhouse gas emissions and kind of hold them in the soil. To do that we need to be on the massive land acreage footprint that is in production now. So, we’re talking somewhere between 340 to 350 million acres that are used every year to produce crops. the more traditional conservation programs aren’t gonna hit that kind of acreage. We’re gonna need something that goes in and says, let’s help farmers you know combine things like no till or cover crops and nutrient management so the fertilizers are not contributing to both water quality challenges, but also climate change. So, then we're talking about a much larger acreage footprint and we start looking elsewhere in the Farm Bill for a way particularly thinking about creative ways in which we can blend some of the other programmatic assistance to farmers with climate change goals or outcomes.

Ariana Brocious: So, another major avenue for climate policies within the Farm Bill would be subsidies or crop insurance programs, right. Can you give us a sense of how climate disruption is already impacting yields and thus some of those programs?

Jonathan Coppess: Where we’re gonna see climate change really the most concerns could be around the crop insurance program, because we are trying to run an insurance program that covers losses and as climate change drives more and more losses. One of the things I’d like to talk about crop insurance, the reason why it's so challenging and the reason why we have a lot of federal involvement and frankly federal dollars going into subsidized and help the program is we all have some familiar insurance, you know, car insurance. But it isn’t the situation where an entire region wrecks its car at the same time. You have a drought where you have a widespread prevented plant scenario in the spring. You could wipe out an entire region. 2012 for example, we took a massive hit because of the drought in the Midwest in the crop insurance program. So, to be able to sort of run that kind of actuarial science and all the rating and issues they use to try to make insurance policy and program work. It is drastically complicated by that you know not unusual or out of the complete ordinary kind of massive event, a water shortage in the West, those sorts of things. And so, people that are looking forward, and trying to sort of put these pieces together are very concerned about what climate change may mean around the crop insurance program because of the way it’s designed now and because the implications we see for a variety of production challenges.

Ariana Brocious: Right. And part of that is because we are growing so many acres of the same crops, right, where a lot of this is monocropping. We have millions of acres of corn and soy and wheat and rice and other things like that. So, what's the argument then for maybe as a way to reduce the liabilities among crop insurance and losing a given crop you know, with increased climate disruption and uncertainty, further diversifying farms then. So, you're not putting all of your yield for any given year in one crop.

Jonathan Coppess: That's a tough question. I mean part of it is we have developed this way over decades. This is not a you know we’re not gonna turn this sort of thing around very quickly. And we’ve consolidated farming and so your operations are bigger and that sort of diversification cuts against all the push that we've seen for decades to try to get better, you know, efficiencies and economies of scale and those sorts of things that the economists love to talk about. But that also we do sort of lead us down into this path and then you’ve got again layered on top of that, not just the farmer but the way the whole system sets up. So, you’ll hear time and again farmers who do try to diversify, by maybe adding a crop. So, let’s add wheat into our corn and soy rotation. Oh, I’ve got no elevator to sell it to. I can’t get a good price for it. There's no market, you know, say in Central Illinois maybe for that kind of diversification. So, there's no easy way to sort of unravel or unwind those things and look towards diversification. Again, one of the examples tying back in the climate change are some of the conservation practices that do promote diversity. So, resource conserving crop rotations where we try to work in, you a different third or fourth crop. Cover cropping, which is a conservation practice where we would go in, if you take your typical corn and soybean operation you go in harvest the corn and soybeans in the fall and then you plant in overwinter crop. Because normally they’re gonna leave that field bare fallow over the winter and into the spring. And now you're doing things that hold soil, keep nutrients from leaching into river’s waterways. And a growing green crop will pull down carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gasses. So, it begins to help capture that. So, that would be one way to diversify conservation that isn't just going from two commercial crops to three or four. And that could be a step along that process.

Ariana Brocious: So, let's step back and take a look at the bill kind of you know as this, large kind of behemoth puzzle that has a lot of moving parts. where have we seen past successes in introducing new component pieces to the Farm Bill or you know new programs, things that do actually change kind of how the money is spent.

Jonathan Coppess: Probably the best historical example for what you just asked is the 1985 Food Security Act. And that was landmark legislation and it’s fascinating when you look at the history because the ‘85 Act came in in the middle of it where the depths of the 1980s farm economic crisis. So, we had a lot of farmers going bankrupt and the markets had struggled and it was a mess. They had high inflation. They had high interest rates. Just a series of economic challenges. At the same time in the 70s we also vastly expanded production. then is expanding acres where erosion is a problem or they’re less productive or there's other challenges to that. So, by the 80s we've gotten not only a farm crisis we got an erosion crisis. We've got soils moving into waterways with pesticides and fertilizers in them, and things like that. So, this ’85 Act is a massive change because we created what we call the conservation reserve program and that was about 45 million acres was the goal to take land out of production for up to 10 years or 10 to 15 years, actually depending on the practice you put on it. So, the conservation reserve program is designed ‘85 to really pull back those acres that shouldn't be in production because they have some environmental sensitivity. The other big one and is in 1985. We added what we call conservation compliance to the farm subsidy programs. And this is key if you think about the politics and the economic situations. So, farmers in the depths of a crisis. And at that time because erosion problem was so significant, Congress attached conservation compliance. So, basically telling a farmer if you did not comply with the way you're supposed to treat highly erodible ground for example, so it doesn’t erode you’ll lose your farm subsidy payments. Or if you drain a wetland to farm it, you'll lose your farm payments. That’s a pretty big move. Now, we can argue about how effective it is and so forth. But in terms of the politics of getting massive change not only was it a big political step, it doesn't cost any money. It doesn't have a hit in the budget because it's not creating new program payments. It's just adding requirements onto the payments that would've been triggered anyway. And so, I think that's kind of an example where you can think about blending some outcomes, farm subsidy payments in particular, are you know taxpayer-funded direct assistance to producers. Are there arguments around that that there should be something coming back in some benefit to the general public who is helping to fund the programs that say look, we want to see better climate resiliency practices undertaken to help. Let’s look at that acre as more than just the crop you're producing but the crop you're producing and ecosystem services they can provide on top of it. The water quality improvements. The habitat improvements or pulling down carbon pulling down greenhouse gasses and storing in the soil for a stretch of time.

Ariana Brocious: I think that's a great example, and I'm wondering what you see from sort of a political standpoint as to the will to do more of that in this next round. Who's pushing for adding more compliance, more requirements, you know, bolstering some of the programs we’ve talked about, what are the sort of political factions that you see playing out.

Jonathan Coppess: Now you’re asking me very tough questions. Because the politics are very difficult around this. You do not see a lot of farm groups or interests you know wanting to expand conservation compliance or take it in a new direction because of course it’s gonna impact or could potentially impact their assistance. It certainly gets even more controversial if you try to apply it to crop insurance. I don't want to leave any impression like this is an easy thing to achieve. It is a straightforward, relatively simple kind of policy concept, but the politics were difficult because we’re impacting so many producers and potentially large amounts of funding. I don't wanna ever sound like a pessimist because we have done big and difficult things in this country and congress has found ways to do big and difficult policy achievements. But it is difficult. And our current political state I think you'd have to be blind to not just acknowledge that it's not getting any easier. And in fact,we are pretty actively making it more difficult if not kind of tearing apart some of the political muscles the things that we need to exercise and use like negotiation and compromise, like deliberation and debate. We've done a lot more damage to those in recent times, than we've improved them and things like a Farm Bill as you've mentioned and those complex and many moving pieces and parts and big federal budget numbers and things like that requires an awful lot of deliberation, good-faith negotiation and ultimately compromise. And we just have not seen much of that lately.

Ariana Brocious: Jonathan Coppess is an Assistant Professor at the University of Illinois. Jonathan, thank you so much for joining us on Climate One.

Jonathan Coppess: Ariana, thanks for having me. It’s great to talk to you.

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to a conversation about the climate implications of the Farm Bill. Our podcasts typically contain extra content beyond what’s heard on the radio. If you missed a previous episode, or want to hear more of Climate One’s empowering conversations, subscribe to our podcast wherever you get your pods. Coming up, how do subsidies in the farm bill actually affect farmers?

Scott Faber: Everyone agrees that we need a farm safety net. We need ways to help farmers weather the ups and downs of agriculture, especially now that extreme weather is impacting farmers’ livelihoods. And I think also it’s the case that most farmers agree that there ought to be reasonable limits on who receives those payments.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton, and we’re talking about the climate and equity implications of the upcoming Farm Bill. Scott Faber is Senior Vice President of Government Affairs at the Environmental Working Group, and Chuck Conner is President and CEO of the National Council of Farmer Cooperatives. 10 years ago Conner said that he couldn’t talk about climate with his member farmers. I asked him what those conversations are like now.

Chuck Conner: I would go far as to say most American agriculture today when this issue came up in the 2009, 2010 period there was great fear among farmers. There was just a thought that climate debate and climate if you will, friendly policies just simply meant somebody was gonna be standing there looking over their farmer shoulders, telling them how to farm and, you know, sort of micromanage kind of situation. And I think over time we have shown them that is not the case. This is about providing the right information to them. This is about providing you know efficiency options. This is about doing it the best that you possibly can. But all in a manner that gives them complete and total control over their land and their farming operations and they're supportive of that and they’re growing stronger every day and I think there's a sentiment out there that this can be win-win. We can be pro-climate, we can be pro-farmer, pro-farm income and we weren’t there 10 years ago

Greg Dalton: Scott, the environmental working group keeps a database of farm subsidies and crop insurance payments. What is your data shown on who gets those payments? Most of those dollars have gone to complex farming operations in households. Tell us where the money goes.

Scott Faber: Yeah, I think everyone agrees that we need a farm safety net. We need ways to help farmers weather the ups and downs of agriculture, especially now that extreme weather is impacting farmers livelihoods. And I think also it’s the case that most farmers agree that there ought to be reasonable limits on who receives those payments and how much they receive. If you’re very, very successful you probably reach a point where you no longer need the government support. And unfortunately, we don't have meaningful limits on our subsidies. There have been efforts to place a real means test in place. Chuck led some of those efforts when he worked for the Department of Agriculture. And the result of those loopholes if you will, is that some very, very large operators are getting millions of dollars every year. I don’t think anyone probably, except perhaps the family members and friends of those operators think that makes much sense. And I think there's probably a consensus between environmental groups and taxpayer groups and farm groups that we need a safety net it needs to really be a strong safety net. But we also need to have reasonable limits on who can get subsidies because they’re so successful. And then the amounts that they get that I can imagine any situation or any individuals who get millions and millions of dollars from the taxpayer; that just doesn't make much sense.

Greg Dalton: Chuck, if the farm bill is written with the notion that we produce too much and need to keep the brakes on. Help me understand the role of subsidies. Are we paying farmers to not produce crops, livestock, or dairy and why?

Chuck Conner: Well, this has been a paradigm of farm policy, Greg, since the 1930s where we really began to make some large crop subsidies during the Great Depression. And, you know, I think you could make an argument in that during those early years of paying at a time that you are trying to get less production. There could be some conflicts there and for many years we had to have government-sponsored set-asides, the sort of keep that check and balance. But having said that, we’re not paying a tremendous amount in farm subsidies right now, Greg, and that's a mischaracterization by some out there. Compared to the farm bills that I worked on for the Senate ag committee in the 1980s we’re playing really a lot less in farm subsidies. So, I don't see those subsidies having the market impact, like they did 15, 20 , 30 years ago.

Greg Dalton: Scott, your colleague, Anne Schechinger found that between 2001 and 2020 farmers received 1.5 billion in crop insurance payments for planting crops in flood prone parts of the Mississippi River basin. Her analysis argued that money could have been spent to retire or restore lands for carbon sequestration benefit instead. Are we spending taxpayer money in the best way in the flood prone areas of the Mississippi?

Scott Faber: Yeah, well and let me reiterate that we need a strong farm safety net; that includes helping farmers obtain crop insurance so they can manage their risks. But there are some important lessons to be learned from the flood insurance program that property owners participate in that ought to be applied to the crop insurance program. Especially where you have folks who are getting repeatedly flooded who have or are farming very wet grounds and because of their repeat indemnities from the crop insurance program are increasing the cost of crop insurance for everyone else. So, there are probably some opportunities to adjust rates to send the right market signals to folks who are farming places that they might not otherwise farm without the government-subsidized crop insurance subsidy. There are also some opportunities to probably make better use of the conservation reserve program, the land retirement program that's been around for many decades so that we’re better targeting those acres at those frequently flooded floodplain lands partly to avoid those government payments right you know if those are lands that are hard to farm, they’re frequently flooded marginal lands. Let's use our CRP dollars our land retirement dollars to try to offer those farmers an easement in part to again avoid the taxpayer cost but also to get all the environmental benefits, especially the long-term storage of carbon in the soil and the wildlife benefits the water quality benefits that would come from restoring some of those lands.

Greg Dalton: Chuck, your thoughts on reforming that. We all know that the National Flood Insurance Program is broken. Congress has tried and failed to fix it. How about climate resilience in terms of crop insurance?

Chuck Conner: Well, crop insurance is a complicated issue, Greg. I'm not discounting any of Scott's points on their face. I think these are always things that we need to look at. There’s been a number of attempts in the past to reflect, to have rates reflect that risk in that particular region in that floodplain so that you know a farmer in McLean County, Illinois, sort of the prime farmland in the United States, is not paying the same insurance for his operation to someone who's farming in the Wabash River floodplain, sort of thing. And I think we've achieved some of that. You know would I stand up here and absolutely pound and say, we’re there, no, I wouldn’t do that at all not even close. But I do appreciate Scott's comments on the CRP conservation reserve program. And I do hope that down the road CRP continues to be a vehicle whereby we can farm as is described the most valuable land and where land is highly sensitive, be able to use programs like the CRP to take that land out of production.

Greg Dalton: Chuck, your group as part of the Food and Agriculture Climate Alliance which has expressed support for climate smart policies under the US Department of Agriculture, which are voluntary incentive-based and focused on commodity crops. Learning from other sectors where the industry of course, prefers voluntary measures first, and those only go so far. What do you expect from those policies can accomplish voluntary, incentive-based?

Chuck Conner: I think they can fully accomplish our objectives here, Greg. And I don't in any way, accept that this is a precursor to something mandatory coming down the pike. I believe we can achieve those objectives. We've done it in the past in agriculture, you know, we had the recollect back to the dust bowl years and all the problems we had with soil erosion, you know, through voluntary incentive-based programs to technical assistance from soil specialists, we have curbed a great deal I would say almost all of those kinds of conservation problems. I see no reason to believe that we can't stem this problem with climate change and the problems that we have out there using the same model.

Greg Dalton: Scott, the two biggest sectors of emissions in the US are the utilities electricity buildings and transportation mobility. Those industries have also said we got this voluntary incremental comfortable we’ll get there without government regulation. That didn't really prove the case. Is it the case in agriculture that voluntary incremental would get us to our climate goals?

Scott Faber: Well, there's no question that farmers can take steps to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and many are already doing so. The real tragedy of our policy right now is that two out of three farmers who go to USDA and ask with their own money, bringing their own money at the table and asked the government to help share the cost of practices to use their nitrogen fertilizer differently or change how they're using nitrogen fertilizer or change how they're feeding the animals or how they’re storing animal waste. Two out of three farmers who asked for government assistance are being turned away because of our misplaced spending priorities. That is ridiculous. And I think every American from across the political spectrum would agree that it should be a big priority for the government to share the cost of those practices. They’re not free, they're not free to the farmer and they work. And I think to their credit, Chuck's organization joined with groups like EWG to support a big increase in spending for this climate smart practices in the Build Back Better Bill that has passed the House and is still pending in the Senate. But we need to make better use of the $6 billion a year we already are giving farmers. We have right now that USDA is giving farmers Too little of that money is going to practices that reduce emissions and too much of it is going to practices that either don't do much to reduce emissions or in some cases even increase emission. So, we need to I think while Sec. Vilsack and his team has done a lot to make climate smart practices a priority and we need more money as has been proposed in Build Back Better. We need to make much better use of the money that Congress is already provided in the last farm bill.

Greg Dalton: Chuck, some of the biggest optimists I talked to across the climate spectrum are people who are interested in soil regeneration. The soil can capture water, carbon, all sorts of things. It's tough to scale. That's pretty upsetting to hear, Scott say that farmers go and asking for climate smart help and they’re not getting it from the federal government. What ‘sbroken? What's wrong?

Chuck Conner: Well, Greg, we’ve had too few resources. I think Scott laid out the problem and what he just answered I wholeheartedly agree with it. I would like to see us you know not only rework some of our existing programs in the farm bill to really give them a climate focus, but obviously we also, you know, part of the reason so many people are being turned away is just you know not enough resources.

Greg Dalton: Well, let's talk about the political and economic context for that. We’ve seen some really big legislation trillion dollars used to be a lot of money in Washington. Now, we’re seeing several trillion-dollar bills go through for COVID. What’s the political and economic landscape right now for a more ambitious farm bill? What do you see in there, Scott?

Scott Faber: Well, you know, I think probably as all of us are talking and your listeners are listening in. Senator Manchin and other senators are meeting to discuss the energy package that would be sort of an alternative, if you will, to the Build Back Better Bill that has passed the House. Congress still has five months they have plenty of time to pass the Build Back Better package or some version of it that includes the $27 billion that the House approved and that Senator Stabenow has so effectively championed in the Senate for these climate smart practices. So, that would be an enormous missed opportunity if we left $27 billion in funding to help farmers reduce greenhouse gas emissions on the table. What a waste that would be. And I think there's not just a really powerful environmental case, right. We know that spending $27 billion on better use of fertilizer, better use of changing what we feed animals, changing how we manage manure. We know those things will reduce nitrous oxide emissions and methane emissions. There's also a really strong business case for making these investments. And that’s because right now US agriculture accounts for at least 10% of US emissions. But every other sector, mostly because of policies we've adopted like renewable portfolio standards and CAFE standards. Every other sector of the economy is taking steps to reduce their emissions except for unfortunately our farmers. The emissions when you look at the EPA's greenhouse gas inventory over time. Those emissions are going up and that's no fault of the farmer. It’s simply because we are eating more and more meat. We are producing more and more meat for growing population around the globe. And when you fertilize animal feed and when you raise animals, you’re gonna increase nitrous oxide, and methane emissions. So, I think there's not just an obvious environmental case for helping to share the cost of these practices. I think there's a real reputational risk to our farmers if we don't help every way we can and use every tool in the toolbox to reduce emissions soon. But, you know, consumers have a big role to play here too. And again, if we double animal protein production and consumption. There's no way we’re gonna meet the goals that we set for ourselves for the climate whether it's the goals that we recently restated in Glasgow. So, we've got to make it easier for consumers to occasionally just once in a while the 94% of us like me who eat meat. I had bacon and eggs for breakfast. The 94% of us who eat meat to occasionally try and replace an animal protein with a plant-based protein to get a little bit more of our protein from plants. And that's not just good for our health or personal health or cardiovascular health. It's not just good for the planet because it would help reduce many of the emissions we talked about the emissions from fertilizing animal feed and the emissions from the animals themselves. It's also really good for farmers because it turns out that America's farmers and the companies that turned plants into a plant-based food here in America are number one in the world. We are the best in the world at producing plant-based foods. There are already 55,000 jobs across the country, mostly in rural places producing plant-based foods. That's a great opportunity for our farmers. And it's one we will lose if we aren’t smart because other countries, especially China, no surprise, are making huge bets because they see what we’re talking about. We need to make some bets in the next farm bill.

Greg Dalton: Chuck, you say the farm bill is about leveling the playing field. Does addressing systemic racism have a place in the farm bill?

Chuck Conner: I think so. Absolutely, Greg, I think we need to make sure that every farm program that we reauthorize in the farm bill, every new program we put in place, whether that's climate related or anything else there has to be a key element of that of serving the interest of the farmers of color. Having served the, you know, a stint at the Department of Agriculture this is not an idle problem. It's been a problem and it proceeded Sec. Vilsack. But I will tell you as well I think Tom Vilsack is working very, very hard to try and reverse some of these patterns at USDA that have roots going back decades and decades.

Greg Dalton: Thank you, Chuck and Scott.

Chuck Conner: Thank you, Greg. Enjoyed it.

Greg Dalton: You're listening to a conversation about the upcoming Farm Bill. This is Climate One. Coming up, historically, black farmers have been excluded from the benefits of the farm bill and faced discrimination from the USDA.

John Boyd: Many Blacks weren't even given a loan application, you know. I was given one, mine was tossed in the trashcan and all kinds of stuff that I personally faced. But the further I went south the more egregious and more blatant the discrimination was for black farmers.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. The U.S. Department of Agriculture is tasked with implementing the programs in the Farm Bill. Historically, the USDA has denied loans and subsidies for nonwhite farmers. I asked John Boyd, president of the National Black Farmers Association, to share his story.

John Boyd: Well, my personal experience with the USDA as far as it relates to discrimination goes back probably 39 years ago to 1983 a very, very long time. My dad and grandfather were totally against going to USDA and doing business with the government. And they always thought that the government and black farmers didn't go together, just never mixed. And maybe I should have listened to him, you know. That’s how I got introduced to it and it was a spiral downhill, so to speak. As far as how they treated black farmers this lender would only see black farmers on Wednesday. One day a week so we would all be in the hallway. I knew these older black farmers in the community they were leaders they were deacons. A couple even held local positions in the county. But this person didn’t waive the discrimination for any of that. He talked low to them as far as bold and downward. Called them boy and negro. All sorts of racial slurs is how it began. And then trying to get a farm operating loan was just an uphill battle. This person spat on me during a loan exchange, called like I said racial epithets tore my application up and toss it in the trashcan. And when I was finally able to get someone to look into it they asked that man. Did you have any problems do you have any problems making loans to black farmers? And he said, well yes, I think they’re lazy and look for a paycheck on Friday. But it doesn't have anything to do with me doing my job. And this person after he was found guilty of discriminating against me and many others in Mecklenburg County, Virginia. He was still allowed to keep his job and moved to another county where he was allowed to retire. And that’s the whole thing with discrimination in USDA. No one was ever penalized or held accountable for the active discrimination. Although we had two federal lawsuits one in 1999 and the other one December 8, 2010 when then former Pres. Barack Obama signed the Claims Remedy Act 2010 into law. So, we had two settlements but nobody was ever fired. No senior person at USDA or no local person for that matter was ever fired for the active discrimination. And as I organized further, I went South Mississippi, Alabama and Arkansas, Tennessee, Louisiana. The discrimination was more pervasive. And so, with many Blacks weren't even given a loan application, you know. I was given one, mine was tossed in the trashcan and all kinds of stuff that I personally faced. But the further I went south the more egregious and more blatant the discrimination was for Black farmers.

Greg Dalton: Well, you mentioned a couple of those settlements 1999 settlement in Pigford versus USDA that was an agreement of about $1 billion where government agreed to pay black farmers. Have Black farmers received what they are owed under that settlement and the other one you mentioned?

John Boyd: Yes, but it took too long. And, you know, it took me 30 years on that complaint. there was a few bills as well that went along with those settlement. So, we have all of the claims were too old, including mine when I first started suing the government. My two years of statute of limitations had expired, so I had to go to Congress and get that lifted, got that passed that allowed all of the cases to go back to 1981 to have their cases. So, any black farmer that filed a case between 1981 and 1997, would be able to participate in the first lawsuit. USDA, one on the motion that they didn't have to notify any Black farmer about the class-action. So, therefore 83,000 Black farmer families came after the filing deadline. The judge wouldn't allow them to be a part of the case. So, I went back to Congress again to have that measure included in a bill that with the help of Chuck Grassley and George Allen some Republicans heading it. And the leader at that time was Ted Kennedy and as he became ill then Sen. Barack Obama and Sen. Biden believe it or not were the lead sponsors of that bill. And they both went on to become president and I didn’t know that was gonna happen but that bill came about. And the bill only let them have those 83,000 Black farmers cases heard based on merit. They didn't divide any compensation. So, I had to go back to Congress again to get the settlement funded for $1.25 billion. And those cases were finally heard and adjudicated.

Greg Dalton: Pres. Biden has directed $4 billion in COVID relief funds toward Black, Indigenous and other farmers of color. Is that money making a difference and is USDA acting more appropriately responsibly this time around?

John Boyd: Well, there’s a few things that I would like to address there. One is then Vice President Biden in South Carolina that we desperately needed a new face at USDA to take on the bureaucracy at USDA. But instead we got Secretary Vilsack for a third term. And I did express to then then President-elect that I thought that Sec. Vilsack was the wrong man for this time in history. And he pressed for us to support Secretary Vilsack. And if things didn't work out to let him know. I don't think that things are working out in my opinion. The bill that provided the 5 billion 1 billion for to improve systems and outreach and set up all these other things at USDA. And then 4 billion for debt relief in the form of guaranteed loans and direct loans. So, 14,000 plus farmers of color were eligible to proceed there. There was no entity involved. It was a government to government transaction. So, why did it take so long? There is no need to hold listening sessions when you already knew who these persons who are eligible, the farmers of color to receive the debt relief. So, why not do it the same way you do subsidies for primarily large-scale white farmers. When the president signs it. It's in the checking accounts of those large-scale corporate farmers within weeks of it passing. So, it took almost a year and then white farmers started suing us or reverse discrimination and 12 different complaints in federal court. And the National Black Farmers Association, and the Association of American Indian Farmers really started fighting back in those federal courts. Two of the courts, Texas and Florida, issued a temporary injunction blocking the aid to the farmers of color. So, right now I'm in federal court in 12 different states. 12 different complaints in various states. Now, the white farmers were very crafty at this, I hate to use this term. They picked very conservative judges very conservative courts that they thought would look favorably upon what they were saying that it was reverse discrimination some new loan program that excluded whites. But they never said they were the ones, they, being white male farmers that were getting the debt relief. The whole 30 years I was asking for it, it was those farmers who are actually getting the debt relief. That's what I was trying to get because black farmers want it. We were getting 30-day loan acceleration our lenders which means they were foreclosing on us. And white farmers were provided with other options under the 1951-S which is the loan servicing for agriculture in this country at USDA. They were getting debt all re-amortizations debt writes down debts written off. And they were getting these options with ease. And Black farmers if where weren’t able to hustle up what we owe the government those that were lucky enough to get loans within 30 days we lost our farms.

Greg Dalton: Well, that’s quite a tale. Thank you for sharing that. Are there measures in the farm bill to address these inequities?

John Boyd: I’m glad you brought up the farm bill because it's something that I would like to see a lot of changes in how they address Black and other farmers of color. And some of the bills that recently passed it gives the secretary of agriculture full discretion to implement. I would like to see that changed. Instead of giving the secretary whoever that secretary is full discretion to implement, give them time ramifications in which to complete the task. For instance, if there was a timetable for debt relief. This should be executed within 30, 60 and 90 days. We wouldn’t be probably wouldn’t be in the boat that we’re in. And the programs that are targeted for farmers of color. We always have to have matching funds from some outside organization to participate in those federal programs. I would like to see those measures taking out of the farm bill. And what’s happened to us historically is we don't receive the checks from corporate America and the others who manage these retirement funds that quickly help other causes have been slow to help the National Black Farmers Association. And if they do, it’s very, very small monetary contributions. Not to say as the president that we’re not appreciative of that – I don't want anyone listen to this say oh my god this people don’t appreciate the help. We appreciate the help at any amount. But for us to really save our farm from foreclosure the average size of a farm mortgage is $300,000. Someone has to be able to write that in order to save that farm and get that farmer a second chance. And we need the form of more direct assistance for farmers such as infrastructure and equipment to facilitate any outside contractor. And that’s something Congress continues to turn a deaf ear to. So, they would give 40 million to food hubs and food banks and 100 million to food banks, but they won't invest in the actual farmer himself, that is the person growing the food. And I’m gonna stop talking there.

Greg Dalton: You mentioned land loss, you know, Black run farms were about 14% of the total in the US in 1920 and today down to around 2%. And small and medium-sized farms have a harder time getting access to capital and technical support. Can you explain the challenges that present to new farmers and farmers of color.

John Boyd: That’s what we’ve been fighting right there. The government needs to invest heavily in new and beginning farmers. And if we don’t, I’m telling you right now this not only will Black farmers be facing extinction but all farmers in this country will be facing extinction if we don't invest in the next generation of farmers.

Greg Dalton: And do you see change at USDA now you talked about the impunity particularly in local offices. Do you see a change now?

John Boyd: Not only local level. And that’s where the changes have to happen. And I’m gonna try to explain this quickly for, 101, for people who don't understand how the government works. You have a new administration that comes in. They have some great ideas that could help all farmers and even maybe even Black farmers and farmers of color. It takes them a year or two to get those ideas into the administration. And by the third year those persons who are career bureaucrats there who are supposed to be implementing this. So, you know, what I don’t like this and I’m gonna slow roll this and I'm going to do this the way I’ve been doing it for 30 years at USDA. Those career bureaucrats always seem to outlast the great ideas and mindstreams of the new incoming administration. And that's what's been happening to Black farmers. We got to find a way around that circle to really put some real hard programs into effect so that farmers of color can start receiving some benefits. And new and beginning farmers can receive some incentives to actually become farmers people. It’s the hardest occupation known to man. And if we don't do some things to do that to entice as my son said, daddy make farming sexy. If we don’t find a way to do this in a hurry, we’re gonna lose a generation of farmers.

Greg Dalton: What avenues do you see in the next farm bill for increasing climate resilience among all farmers, Black farmers, Indigenous white farmers.

John Boyd: Yes, well, you know, climate is a very big issue here. I think it’s an issue that should have been addressed 25 years ago. But we’re just now getting to it. It's just now front and center. When I first started farming in 1983, we were planting corn in March. Now, I’m planting corn in May and it’s all due to the changing seasons. When I first started farming, I would be finished harvesting soybeans by October 15th. Now I’m just getting in the field at November because it starts to rain and then I can’t get out there. The seasons are changing. Planting season is shorter. And the harvest season is shorter. All of those things are due to climate change. These severe summers, maximum heat, you know. As a kid you didn’t see 110, 111° days when I was a kid. You know, if you got up to 100 man, we thought all hell was breaking loose, you know. So, now you see triple digits and some of us were like, oh it’s gonna be a hundred again today. Crops can stand two days of hundred-degree heat and then you have to do something. You’re gonna have to irrigate or you begin to lose or take damage in your crops. But I'm saying that because the climate is changing. We need to address it. We need to help fix it. And it's not just a farmer thing. It's a world thing. Where the whole world is gonna have to participate in order to make our climate better. It’s something that we can’t continue to take for granted people. my grandfather said, if you don't take care of the land the land won’t take care of you.

Greg Dalton: John Boyd, Jr. is President of the National Black Farmers Association. John Boyd, thank you for sharing your story and your insights on the farm bill on Climate One

John Boyd: Thank you very much for having me.

Greg Dalton: On this Climate One... We’ve been talking about the equity and climate implications of the upcoming Farm Bill. Climate One’s empowering conversations connect all aspects of the climate emergency. To hear more, subscribe to our podcast on Apple or wherever you get your pods. Talking about climate can be hard-- but it’s critical to address the transitions we need to make in all parts of society. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review if you are listening on Apple. You can do it right now on your device. You can also help by sending a link to this episode to a friend. By sharing you can help people have their own deeper climate conversations.

Greg Dalton: Brad Marshland is our senior producer; our producers and audio editors are Ariana Brocious and Austin Colón. Megan Biscieglia is our production manager. Our team also includes Steve Fox and Sara-Katherine Coxon. Our theme music was composed by George Young (and arranged by Matt Willcox). Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.