A Tale of Two Cities: Miami and Detroit

Guests

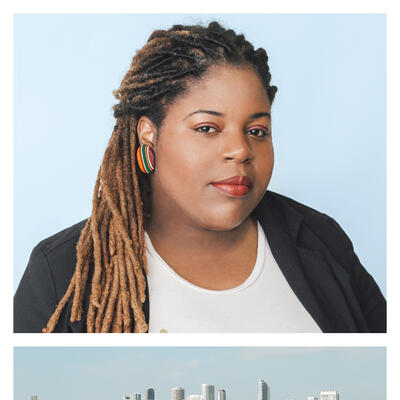

Valencia Gunder

Jesse Keenan

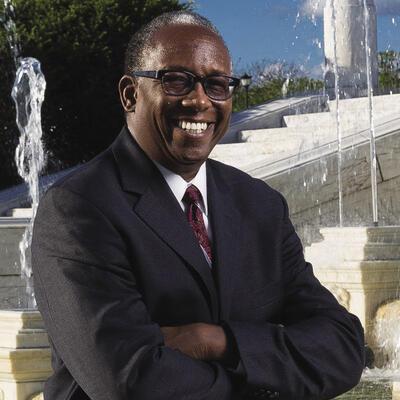

Guy Williams

Summary

Climate change is upending Miami’s real estate markets, turning one of its poorest neighborhoods into some of the most desirable real estate around. It’s a phenomenon known as “climate gentrification,” a term coined by urban studies professor Jesse Keenan.

In a 2018 paper, Keenan writes that while gentrification is most often driven by supply – that is, a surplus of devalued property that invites development and transformation – climate gentrification is the opposite.

“[It]is really about a shift in preferences and demand function,” says Keenan. “And that's a much broader phenomenon in terms of geography and physical geography or markets in some markets than any kind of localized gentrification in a classic sense.”

In other words, as people are attracted to areas of lower vulnerability, developers see an opportunity to make a killing. Valencia Gunder, a community organizer and climate educator in Miami, recognizes the irony. She says that in that city’s earliest days, Haitian, Bahamian and Caribeean immigrants were barred from living in the tony beachfront areas.

“Black people had to live in the center of the city, which is different than most America, because usually low income black communities are in lower lying areas…and so everything they did that they thought they were doing to hurt us, actually ended up helping us in the long run.”

But there’s only so much Little Haiti to go around. As longtime residents are being priced out of their community, climate change isn’t helping matters.

“Once the water comes in, Little Haiti will be beachfront property,” Gunder predicts.

“Bottom line, it’s gonna be beachfront property, it’s going to be the new shore. So it's become like the hottest toy on the shelf.”

Related Links:

Make the Homeless Smile Miami

The CLEO Institute

100 Resilient Cities

Climate could exacerbate housing crisis in South Florida (Sierra Club)

Climate Gentrification: from theory to empiricism in Miami-Dade County, Florida

Magic City Innovation District

U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit

Retirees flee Florida as climate change threatens their financial future (Money)

Detroiters Working for Environmental Justice

Portions of this program were recorded at The Commonwealth Club of California in San Francisco.

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One, changing the conversation about energy, the economy, and the environment.

On today’s show, climate change is turning one of Miami’s poorest neighborhoods into some of the most desirable real estate around.

Valencia Gunder: Once the water comes in, Little Haiti will be beachfront property. Bottom line, it’s gonna be beachfront property, it’s going to be the new shore. So it's become like the hottest toy on the shelf, Little Haiti.

Greg Dalton: But there’s only so much Little Haiti to go around. And as hurricanes pummel the east coast and rising seas lap at Florida’s shoreline, relocating to midwestern cities like Detroit is looking more and more appealing.

Guy Williams: We would love to have people coming here and helping be here and join in the prosperity that's possible in the city, yet we have things to take care of first.

Greg Dalton: A tale of two cities – Miami and Detroit. Up next on Climate One.

Greg Dalton: In Florida, the seas are rising – and so are the rents. Is it time to flee the Sunshine State for Motor City?

Climate One conversations feature oil companies and environmentalists, Republicans and Democrats. I’m Greg Dalton.

The term “climate gentrification” was coined by Jesse Keenan of Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. In a 2018 paper, Keenan writes that while gentrification is most often driven by supply – that is, a surplus of devalued property that invites development and transformation – climate gentrification is the opposite.

Jesse Keenan: Climate gentrification is really about a shift in preferences and demand function…and that's a much broader phenomenon in terms of geography and physical geography or markets in some markets than any kind of localized gentrification in a classic sense.

Greg Dalton: In other words, as people are attracted to areas of lower vulnerability, developers see an opportunity to make a killing. Valencia Gunder, a community organizer and climate educator in Miami, recognizes the irony. She tells us that in that city’s earliest days, Haitian, Bahamian and Caribeean immigrants were barred from living in the tony beachfront areas.

Valencia Gunder: Black people had to live in the center of the city which is different than most America because usually low income black communities are in lower lying areas. It’s opposite here in Miami. And so everything they did that they thought they were doing to hurt us actually ended up helping us in the long run.

Greg Dalton: Gunder’s family has been in the area for generations - even before Miami was a city. She says that Miami’s history of marginalizing its black residents goes back to its beginnings as a tourist destination.

PROGRAM PART 1: VALENCIA GUNDER

Valencia Gunder: So historically, when Julia Tuttle and Henry Flagler came to South Florida to create the now formal Miami they wanted to create this tropical paradise that the snowbirds will come from the north in the wintertime when the rest of the country is frozen to have this tropical paradise, and you don’t have to leave the country for. So when they started to build Miami they were building it to be a tourist attraction. They never had the intention for it to be a place or a city that it is now. Like it was supposed to be like this seasonal place where people come. One of the first buildings they built was a hotel.

So that's what they were building it for and of course during segregation, Jim Crow, even though they had to go get the Bahamians and the Haitians and the Caribbean folks to build on Miami because they didn't know how to build on the swamp, they would not allow the black people to live on the beach. Black people had to live in the center of the city which is different than most America because usually low income black communities are in lower lying areas. It’s opposite here in Miami. They force us to the middle of the city they also built this highway I-95 straight through our community.

And so everything they did that they thought they were doing to hurt us actually ended up helping us in the long run. Now that Miami is ground zero for sea level rise the beach will be underwater, we don't know when but it's going to happen science already proved that. And usually when storms hit the eye of the storm doesn’t come through the center of the city which is where like Overtown, Allapattah, Liberty City, Little Havana,which are like all of the low income communities of color, all sit in the center of the city. So we don't usually take the bulk of the storm. So they deem us, “weather safe”, right. And so now we’re starting to see -- I mean, I've been in Miami 34 years and some of the things that I see happening inside my community now I wouldn’t have thought 20 years ago. So it's interesting because we were forced to live in these areas and now we’re being forced out of them.

Greg Dalton: And what's happening there, there's a billion-dollar development in Little Haiti. I've read about Peter Ehrlich and other developers moving into that because they see the future, the desirability of the higher ground, more hurricane, safe, as you said. So what's happening as people starting to realize that sea level rise is soon if not, and now in Miami?

Valencia Gunder: Right. So what the science says that we’re gonna get 6 feet of water. Little Haiti sits 8 feet above sea level rise and that is not high for most Americans but that’s high for Miami, I always have to tell people that. Once the water comes in, Little Haiti will be beachfront property. Bottom line, it’s gonna be beachfront property it’s going to be the new shore. And if that happens 50 years from now 60 years from now, that's what the reality is. So it's become like the new or the hottest toy on the shelf, Little Haiti.

And so yeah, that's where the Haitian community settle when they came into Miami just like how our Cuban population went to Little Havana and now Dominican population went to Allapattah and now Bahamian community in Coconut Grove. That's just what they did and they made their own community and put they brought their culture their food and their families there. But it does make them extremely vulnerable for many reasons. One, because it’s gonna be beachfront property. So it's prime real estate. Secondly, it is 10 minutes away from the airport, it’s 10 minutes away from the beach. The existing beach now and it is weather safe all at the same time.

And also 85% of the people that live in Little Haiti are renters. So that makes them extremely vulnerable. And the median household income last I checked was between $18,000 to $20,000. So people are living in extreme poverty. Then you have the immigration status to make them even more vulnerable. So it makes them extremely vulnerable. So even bringing in a medium-size development would shift that entire community. So a massive development like Magic City or Legion East or it’s so many, because it’s four of them coming into Little Haiti it’s not just Magic City. Magic City is just the largest one. People can’t survive that.

Greg Dalton: So what does that mean does that mean that -- what would you like to happen? Because some people would say that investment coming into an area can be helpful, create jobs. If you do, for those who do own property there, it’ll increase their property value. So are there some people who are winning and some people who are getting pushed out?

Valencia Gunder: Well, some people who are winning but not the Haitian community. The Haitians are losing as a community they're losing in this fight. I’m not against development I don't want anybody to ever get it twisted but I am against displacement. Now I do know of models around the country where you have more inclusive development that's happening, like co-ops are included low income housing workforce housing community benefits agreements that would secure jobs and educational opportunities that help build those communities up, right.

I’m in fear that that is not happening with the Haitian community here in Miami. And I have been a part of the fight with organizing these communities around this issue and I have not seen a community benefits agreement presented to our community that I am satisfied with.

I know Commissioner Hardemon has been trying his hardest to make sure that the community get as much as they possibly can to help benefit them. And he has tried his hardest to make sure that, you know, the community gets what’s best but it has not been easy. And that to me is still is not good enough when I've seen like community benefits agreements from California, and community benefits agreements at Harlem, right, where it’s like hundreds of millions of dollars going and pouring to community that’s securing housing and jobs and healthcare and stuff like that. So I believe that we can do way better than what we've been doing even though it's been people to the table trying to make sure that happens.

Greg Dalton: And when you're talking to people in Little Haiti in these conversations, is climate identified as one of the drivers of this, or is climate too far an abstract thought about, you know, glaciers and polar bear, or is climate connected to what's happening?

Valencia Gunder: Well, a few things. One, especially in the Haitian community most of them are climate refugees already from the earthquake and the hurricanes that happened in Haiti. So that’s the thing most of them are climate refugees. So climate is already tied to them every day. It’s not like a conversation you have at the table at home because climate and climate change is something that they’ve been dealing with for a long time. They grew up on the island, right. We know that the islands are being affected by these epidemics every day and then most of them had to leave their home country to come over here for those reasons. And also they were feeling it, right, we lack tree canopy in our community so as extreme heat. They noticed that they are being pushed out like people who live in mobile homes and like certain different apartment complexes. They’re being pushed out, small business owners are being pushed out of Little Haiti also, Haitian owned small businesses.

And they had that undertone just like they did in Liberty City that I was telling you about like they’re telling you like we know they’re coming for us because it doesn’t flood over here and we don’t get this over here. They know that it’s coming they just never had nobody to give them the science and the evidence until I thought doing my workshops. They knew it, but it's not like now if you go into Little Haiti or these areas they’ll probably bring up the term climate gentrification because they now know it but at first they will talk about the actual action of it. But like they would probably never say like, oh, you know, we have more than 350 parts per million of carbon in the air,they won’t give you all of that. But they will let you know that they’re taking our communities because Miami is going underwater. They know that for a fact.

Greg Dalton: There’s a real debate right now in the Democratic Party on the left, prompted by the Green New Deal about how ambitious in scope the Green New Deal should be. Should it attack jobs and economic equity and some of the problems of capitalism and all these things and some people are saying, whoa, that's too much. Other people are saying, hey, these things are all connected jobs and racism and redlining and climate they're all part of the same systems. How do you talk about things that’s connected?

Valencia Gunder: Well, I always tell people that climate is a threat multiplier. So you're already having social ills in your community, climate is only gonna make it worse. And we focus as a society more on adaptation than mitigation. And when you continue to focus on adaptation, adaptation, adaptation, that’s gonna cause wars, like people are going to start like, I think that’s what you gonna have your classism issues and your poverty issues and things like that because adaptation you have to have money at that, right. So if you don't have money or power or class then you’re gonna have a problem ultimately, right.

So I think about that when I go talk to communities, right. So I try to teach them about how you can do things to adapt and mitigate in your community every day to prepare for these things. I'm really good with mixing medicine and candy, right because some people don't want to sit through a science class. So I do like this really like fast blast so teaching people about climate change, sea level rise like I use two cups of ice and water to teach sea level rise. And it’s extremely easy people remember it and I always get people like ten things to do in their house every day to help lessen their carbon footprint. And I know that’s nothing to like a big time scientist before a person who doesn't even think about climate change that's a big step, right.

And then ultimately I bring climate to their front doors, right. So the housing piece is a huge one, right? Everybody knows climate gentrification they’re gonna try to contact the neighborhood. But also your health, are you wondering why you're getting shorter breath walking down the street when 20 years ago you could have did it. It’s not just your age, right. It’s extremely hot we are having what, 90% about a year 80° and up in Miami, extended heat waves. We don't have cooling stations in our communities; we barely have trees.

So it’s those type of things that are happening that people need to know and understand; the Zika outbreak scared a lot of folks. Even though they said it was only in Wynwood but last time I checked mosquitoes had wings. And people were nervous about it, right, and that's when I took the opportunity to educate people on what was happening, why it's happening. And then I also teach people how this will actually affect our food, right. That's a huge thing people don't know and understand that we live in a peninsula. A storm hits like Hurricane Irma it’s only one way in and one way out of Miami. So we have to know and understand what we need to do to survive like we’re not even on an island, we’re in a peninsula and we’re at the bottom of it.

So thinking about those things and then teaching them about how we're sitting on limestone and not bedrock like other cities, you know, so the water is not just coming from the side it’s coming from underneath. And that also help people understand like what they can do and what they're facing every day. And it's just tieing it to them like they care about their food, they care about their health and they care about their housing. And those are the three things that I usually tie climate to, to make them understand and care. And that usually is what people love to see me coming and to talk about and discuss because they want to see how they can survive this thing that’s gonna happen to our city.

Greg Dalton: Valencia Gunder, a climate change educator and the founder of Make the Homeless Smile in South Miami. You’re listening to Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. Coming up, Gunder takes us on a walking tour through Little Haiti – and explains why it’s ground zero for climate gentrification.

Valencia Gunder: Because there’s no Little Haiti unless you have Haitian people with Haitian culture. So they are literally wiping it away little bit by little bit.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton, and we’re talking about ways to mitigate climate change by building more resilient cities. Later, we’ll walk through the neighborhood of Little Haiti with community activist Valencia Gunder.

My next guest Jesse Keenan teaches urban development and climate adaptation at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. In 2018, he co-authored a paper focusing on the impact of climate gentrification in South Miami. But his interest in the topic was sparked years before, in another part of the world.

PROGRAM PART 2: JESSE KEENAN

Jesse Keenan: I was actually inspired by Copenhagen. And in Copenhagen what they had done it was one of Europe's really first real major projects to invest in a low to moderate income neighborhood that had a lot of environmental exposure in terms of impacts and flooding and the like. And they went in, they redesigned they reengineered they made a lot of investments. It was really a very beautiful project. But it had the unintended consequences of creating a set of environmental amenities that actually attracted investment, attracted new tenants and operated indirectly in an unintended way to drive out the very people that they had sought to protect.

And in my mind climate gentrification has a couple different pathways. The first pathway is that people are moving from an area of high exposure to a low exposure and that can work across scales and time horizons. So it can be from neighborhood to neighborhood, district to district region to region. Certainly from South Florida to Central Florida or you know, state to state or transnationally.

The other component of it is a kind of inverse gentrification and a cost burden pathway as I call it. In the sense that really only the wealthy can afford to remain by virtue of the carrying costs associated with it. And finally in drawing immediate inspiration from Copenhagen in this case is the climate resilience pathway, which is really the unintended consequences when we go in somewhere to put in those hazard mitigation investments and other resilience interventions that help stabilize and preserve something. We actually have sometimes there's this proposition where you're actually increasing its valuation and that may be unevenly distributed even between homeowners and renters across incomes or whatever that may be and that may lead to the unintended consequences.

So thinking all of this through I think in my mind the classic model of gentrification is exactly what you suggest, which is that it is about a shift in or a shift in supply. It's about developers who come in they see some value that hasn’t been captured they take that risk or non-risk depending how you think about it, they produce that supply it kind of engenders the demand over time. But it's really supply driven and it's very somewhat episodic and localized.

Climate gentrification is very different because climate gentrification is really about a shift in preferences and demand function. And that is a much broader phenomenon because if you're talking about a shift in demand and a shift in consumer preferences, let's say in case of let’s say may be a high elevation relative to sea level rise it may be in the area in California where you have historically less burn zones frequency of forest fires. Whatever that relationship may be that's a much broader phenomenon in terms of geography and physical geography or markets in some markets than any kind of localized gentrification in a classic sense. And I think that that distinction at scale in the order of magnitude of what it means to have a shift in demand should put us all on notice as to the long-term implications of what climate gentrification really means.

Greg Dalton: So in Little Haiti for example, what do you think about there's the Magic City project that this billion-dollar project in the neighborhood that’s 8 feet above the sea level in Miami immigrant population. How do you see Magic City?

Jesse Keenan: It is an immigrant population but it's also a uniquely American phenomenon of Haitian Americans for several generations now and is a critical component of the life and vitality of Miami. I think in terms of thinking about what that project and others like it represent are several things. One, this has been infill gentrification that's been in the making for a long time. I think to say that climate change or climate gentrification from a causal point of view or a way to decision-making is, you know, I don’t think there’s any empirical evidence. But maybe that doesn't matter because in the long-term this high elevation it may not matter to explain one's motivations now, but in the long term it's going to be part of a broader trajectory of displacement and that's a huge challenge.

The other component that I think this project represents is the idea of Miami21, which is their local zoning form-based zoning code which in some ways has been very successful. But there is an exclusion in the special area plans, SAPs as they call them, which essentially once you get 9 acres together you can essentially pull that property together and basically do almost anything you want. That isn't exactly true, but it's given them free range. And I don't think there's been a strong counterpoint unfortunately, although I think there’s great people in the city of Miami from the planners and those who are engaged in capital planning like they just don't have the tools to be true advocates for the civic realm and for local populations like those living in Little Haiti to really push back on some of the impetus which is unbounded development there. And of course we have to think of all of this is in the context of Miami there is no state income tax in Florida. And you have to think about this is a kind of double-edged sort of development in the sense that they are entirely reliant on these on the revenue to have any kind of investment in adaptation resilience going forward.

So it represents I think hopefully a turning point where there is perhaps a public advocate or some formal agency and I mean agency and truly the agency of the people to not necessarily have these kind of ad hoc community benefits agreements that kind of indirectly push the project forward. But a more refined sensibility, if not quantitative set of measures about what those externalities are in terms of loss of affordable housing, displacement, storm surge, storm water impacts, whatever that may be. So that we can and sometimes well I would just say historically that it’s been references ideas like impact fees and things like that. So I think we need to swing the pendulum back in favor of understanding the externalities and the negative externalities of these types of development.

Greg Dalton: So if I heard that correctly Miami needs development, it’s a land development dependent economy. So it needs to develop more land in order to pay for the adaptation to protect what's already there.

Jesse Keenan: The one qualification I would say that's partially true but it doesn't necessarily mean that you need to develop more land. And I actually think that, you know, in the definition of adaptation itself that is the IPCC or, you know, the formal definition, it's both about the moderation of harm, but also the exploitation of opportunity. And I think that's important to understand that in a place like Miami, but many other places there's an opportunity for sustainable urban development to think about densification of housing to utilize that value creation for the promotion of inclusionary housing and affordable housing. To think about accessibility of mass transit to think about all of the perhaps positive values that come along with sustainable urban development in a place like Miami. I don't think it’s necessarily about developing new land as much as it’s thinking about strategically the opportunities that may arise. Now that doesn't mean there won't be severe consequences in terms of even the acceleration of displacement in some parts of town and that’s for the city of Miami to decide for themselves. But I do think in some areas on the right circumstances that represents a strong counterpoint to what is otherwise a fairly arguably bleak economic horizon.

Greg Dalton: So I was there and I went on a little cruise around the bay. I wanted to see these waterfront homes multimillion dollar homes. And there is a development site, right and I think it's the Bayfront Park near Brickell what will be Miami's tallest skyscraper looks like it's basically surrounded by water. Help me understand how that's going to work how someone in 2019 is sinking hundreds of millions of dollars into a waterfront tower in Miami.

Jesse Keenan: Well, the engineering is of a certain degree of maturity particularly as it relates to resilience engineering, which is one of the categorical components of resilience in purely descriptive terms. Is that you can build an island anywhere you can largely service that island. The question is how does that connect urbanistically, how do people benefit how do tenants get there, right. So if the streets are flooded I mean just intermittently flooded from inundation not necessarily sea level rise. If you can't get the adequate power distribution there, you know, whatever those service deliveries may be of which you may be dependent entirely or partially on, that will be the ultimate metric from which success within the useful life of that tower will be determined. Because this is what we have to think about is that, you know, you’re building a building that has a useful life exceeding well, should exceed arguably a hundred years. In 100 years where will that be and from an expected value that is probability times future value; what is the impairment on the value of that asset from an investment point of view. I would think it would be significantly impaired.

Greg Dalton: And you've written that potentially planners and developers ask the question whether economically and ethically it’s desirable for buildings to have a shorter useful life. Should we be thinking about buildings that last 10 years rather than 30 years because we don't know what the waterfront future holds in this country?

Jesse Keenan: Yeah, I think as an interesting analytical counterpoint to the idea. And certainly this has been within the realm of experience of human settlement for thousands of years is thinking about degrees of permanence, durability and capital investment in the extent to which shorter useful life assets or buildings may actually be a superior outcome. Now that doesn’t mean we have to compromise the quality of housing or compromise people's life and safety, or public realm, not at all actually I think there's some points some strong design elements to the contrary.. But it does help us think about not just the idea of building codes and buildings as a kind of reliability or resilience functionality but actually thinking about land-use. And I think that's the conversation we need to have it’s not necessarily about the buildings themselves but what is a responsible allocation of land resources going forward.

Greg Dalton: And you've also said that safety is the foundation of professional license. So do planners and architects have an ethical responsibility to say like, look, I'm not gonna build that project because the developer might get their money out and be gone before climate impacts come, but is it, do planners and architects say, look, that's not an ethical project because of what will happen to that?

Jesse Keenan: Well I would draw, I would actually say it’s architects and engineers less so with planners in terms of their professional licensure. But I think it's not so much about the ethics I think the ethics can play a part of it for sure, but it's actually about their own professional liability, right.

Greg Dalton: Who gets sued for what.

Jesse Keenan: That’s right. And the standard of care, particularly which is determined really entirely by your local peers and local practice is you know, in some cases there may very well be circumstances where this is an inordinate risk and it may not be one that you can manage or ensure for and that very well may dictate your capacity to deliver services. And also by the way it also may really fundamentally challenge your own professional ethics. And I think for the AIA and others that is the American Institute of Architects and others there is very much an emerging movement for a number of years now both adaptation and resilience context to think about that interface between professional ethics and in the environment.

Greg Dalton: That was Jesse Keenan, professor of climate adaptation and urban planning at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design. You’re listening to Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton.

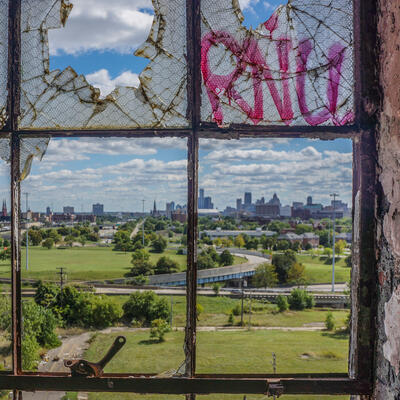

Earlier, Valencia Gunder told us about the very real effects of climate gentrification felt by Miami’s poorer communities. I wanted to see its impact for myself, so we headed out for a walking tour of Little Haiti. The neighborhood is soon to be transformed by the coming of the Magic City Innovation Development.

PROGRAM PART 3: VALENCIA GUNDER – LITTLE HAITI

Valencia Gunder: So right now we’re at Northeast 2nd Avenue in 59th Street in Little Haiti which is like Little Haiti’s downtown. We’re standing right in front of the Caribbean Marketplace which is attached to Little Haiti’s Arts Center. It’s surrounded by Haitian business, small business and things like that. Colorful.

Greg Dalton: Yeah.

Valencia Gunder: You can hear the Caribbean music, you can smell the Caribbean food. You see the Caribbean folks here being great.

Greg Dalton: So we’re looking at some storefronts recently closed storefronts. What are they, what used to be there what happened?

Valencia Gunder: So they were small businesses, Haitian owned businesses that used to be there. A few months ago they were all evicted at the same time. They all closed their doors in the same day. They try to fight it as a community, the community tried to step up but it just could not do it because the building is actually owned by somebody else. They can’t afford to stay there and quite honestly, these new developers and investors don’t want those types of restaurants or businesses in their community now. But that’s just something that the people of Little Haiti or just communities of color come to Little Haiti for in the first place, right. The culture, the fact that we can get Haitian food here, get Haitian culture here and honestly, they are taking it away, they are stripping it away so Little Haiti won’t even be Little Haiti anymore. Because all of the businesses are leaving and all the culture is leaving and all the residents are leaving.

So what's happening is we’re starting to see transients, Northeastern folks moving down to Miami. We’re starting to see a lot of tech industry coming to Miami we’re starting to see a lot of people from the beach come over to Little Haiti and they are actually whitewashing the culture and communities like Little Haiti. Because there’s no Little Haiti unless you have Haitian people with Haitian culture. So they are literally wiping it away little bit by little bit by displacing the business owners and the residents.

Greg Dalton: Valencia Gunder, community activist, climate educator and Miami native.

Coming up, we’ll talk with Guy Williams, president and CEO of Detroiters Working for Environmental Justice, about the ways that city is rising from the ashes of the Great Recession.

Guy Williams: For those of us who are looking to have a carbon free economy that's not driven by burning coal and other derivatives of that kind, it’s important to work on how the people employed in those industries can find gainful work and provide for their families in other ways.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton, and we’re talking about the effects of climate change on two cities. With more and more frequent hurricanes beating down their doors, longtime Floridians worry for their safety and property values. Formerly poor inland areas are being remade into trendier – and more expensive – neighborhoods. Gradually, for whatever reason, some Florida residents are looking to relocate. One city poised to benefit from domestic climate migration is Detroit.

My next guest, Guy Williams, is president and CEO of Detroiters Working for Environmental Justice, an organization focused on the social, economic and environmental health of the motor city. One benefit of climate change is that Michigan is already having warmer winters. And that, along with affordable housing and a revitalized economy, could bring a flock of snowbirds to the Midwest. Williams hopes Detroit will be ready.

PROGRAM PART 4: GUY WILLIAMS

Guy Williams: There's a lot of comment about climate migration that has places like Michigan as places that people will want to come. The challenge I would say that those of us are here now and who are activists on climate or concern about is how are we really ways as a city and a region to deal with climate change, and maintain or best case improve quality of life conditions. Where my organization Detroiters Working for Environmental Justice is part of some different research going on for example, about the impact of heat on housing and the residents of different types of housing.

We know that the storms that are changing nature and becoming more frequently and much more intense or expanding the level of flooding in a region, things of that nature. So we would love to have people coming here and helping be here and join in the prosperity that's possible in the city yet we have things to take care of first before, you know, it’s gonna turn out the best.

Greg Dalton: I was in Detroit a few years ago with my family and saw what's happening the gentrification, young white couples pushing a stroller around we had dinner downtown and they said the food came from an urban farmed a mile away where there was a farm or there had been housing that had been I guess torn down when a lot of people left the city. And I've often said that if young people say what should I do in a climate future, I’d look at Detroit and say it's a growing city there’s affordable housing, there's access to fresh water, they’ll have milder winters. How does someone working on this in Detroit respond to an outsider like me saying something like that about Detroit?

Guy Williams: Well, as I started the train of thought earlier. We're really concerned about the future of Detroit residents who are here now. Well, the level of poverty the challenges with our education system the difficulty for residents to access the abundant land that's available. There is a sense that the resources that are coming today are not really benefiting the whole city broadly. On a positive note, there's been a very powerful body of work just recently completed by the city's office of sustainability and our organization was very vital to the planning and community engagement around that document. It's called the Detroit Sustainable Action Agenda and one of our primary goals which I feel we achieved was to build the visioning in this first blueprint for city government from voices from the neighborhood level.

So when you read the report, you'll see that it's organized around a few primary guiding principles like creating a healthy, thriving place for people to live that we’re pledging to take on the issues of affordable and quality housing that the processes of city government are going to become more equitable and focusing on green options, things of that nature. So it's only been out a few weeks yet. It's these kind of frameworks that I feel hold a lot of promise for creating a different way of operating in the city that will support the people who are here now truly and fully accessing all the abundance that's here now.

Greg Dalton: One positive thing that happened recently is Detroit Renewable Power, very interesting name. The city's decades-old and controversial solid waste incinerator, shutdown. I remember driving by that and seeing that, you know, big incinerator north of downtown near downtown. Was that a big win?

Guy Williams: Oh, absolutely it’s a big win for most of us as often is the case when there's a transformation in the economy. There is a challenge initially at people who end up becoming unemployed, needing to find other places to work and such is the case, I believe, for many folks who are working at the incinerator we call it. However, the location of it the repeated violations of the permit that exist with a set of permits that were existing, even on the best day the lack of protection that those permits would afford people all were reasons that many of us have worked for several years, some since even the 80s before it was built to not have that there. Myself, I’ve been involved for over 12 years fighting that and looking for alternatives to the waste stream. And so one of the elements of the sustainability action plan and also that is informed in some part, by the Detroit Climate Action Plan that our organization help to develop is a formal strategy about solid waste.

So now that we’re not burning everything in the middle of the city we still need to step up and have a creative and demonstrably better way of dealing with waste and ideally one that helps drive a positive economy in the city while affording us cleaner air. So we feel that is very possible. And groups like Zero Waste Detroit and Breathe Free Detroit are working hard with the city government on fashioning a just transition for workers and what do we do about recycling and bringing in businesses that can manufacture clean product process with some of our waste stream, things of that nature. And let’s not leave out composting, there's a lot to be said about that.

Greg Dalton: You mentioned a just transition. What’s the vision for a just transition in Detroit?

Guy Williams: Well, the vision I would say is still being built. But you do have the example we just discussed and there's also more recent example in a local steel mill that slated to layoff, I don't know if it's permanently but certainly for several months layoff a couple hundred people. And so for those of us who are looking to have a carbon free economy that's not driven by burning coal and other derivatives of that kind. It's important to work on how the people employed in those industries can find gainful work and provide for their families in other ways. So I would say that that's a vision that's under construction at the time.

Greg Dalton: And how do you see the big kind of revitalization efforts. Ford wants to transform the old train station which is kind of a carcass very visible carcass of decay in Detroit I think Chrysler's planning another factory. How do you view the big auto companies which have moved a lot of jobs out, you know, saying that they might move some jobs back in?

Guy Williams: Well, most research on public subsidies that I'm aware of they tend to show that the job promises and the economic impact always falls short. So there's a lot of well-deserved skepticism around it. Obviously, having a huge abandoned building like the central train station refurbished and put back in productive use that's a good thing in and of itself. It’s just that what cost and how do we as a society afford the same kind of economic opportunity for advancement to residents who aren't a Ford, you know, they're not a multi-billion-dollar global corporation, but they are entrepreneurs who we also know that small businesses for years and years have been driving the most expansion in economies. It’s not the biggest companies it’s the small ones.

Greg Dalton: What are the paths for green jobs. You mentioned just transition, we used to hear a lot about green jobs, solar installation. What are some specific jobs, low skill jobs available to people in this cleaner future that you're trying to build a vision for?

Guy Williams: Well, one of the things that our organization our nickname is DWEJ, short for Detroiters Working for Environmental Justice. What we've done is we've been involved for several years training people in the construction trades. And we started a subsidiary organization that's a general contracting firm called Future Build Construction Group. So we believe that part of the solution is equipping people with the skills and connections and opportunity to participate in rebuilding the city. Construction has a very strong, has a very strong path to grow in the city of all kinds residential, commercial, and the major infrastructure partners alike. So that's one area where not only can people gain employment. We would hope that in the transformation to a more green economy that those jobs will also be working on homes that are more energy-efficient, that they have low toxic constituency in the parts and we’re doing more reusing of building material through deconstruction that will also help to address the waste stream.

Greg Dalton: Right. And in terms of there’s been some -- the mayor has a city climate action plan, is that a robust document, is that on target in terms of painting a future for Detroit to adjust to this influx of jobs and make sure the gains are distributed equally and prepare for a future with more people and a different kind of future?

Guy Williams: So just to clarify a little bit. There are some very positive stands that the mayors has taken on sustainability. However, the actual Detroit Climate Action Plan was written by a broad coalition of folks that was convened by DWEJ over a five-year period from 2012 to 2017 our report was published. And I mention the sustainability action agenda that's come out just recently, you will see a bit of a bridge and goals and activities that are the city is making commitment to from one document to the other, which is great. And one breakthrough I would say is the City Council also in the last few weeks passed a brand-new greenhouse gas ordinance where they're committing to reductions in generation of greenhouse gas through municipal operations. I believe their target is 35% reduction from the initial measure levels in 2012. They want to reduce 25% by the year 2024 and they also want to drive as a companion to that total greenhouse gas emissions in the city about 30% by 2025.

And there are some longer-term goals that go out to 100% reduction in 2050. So that’s setting up a framework for proactive conversations about the building envelope of any construction that's either existing or to come. It sets up opportunities for looking at how those facilities are powered. And to your question about jobs, when you take a little bit more of a regional view or outside the city view. Wind farms, solar energy there's policy options around distributive clean energy that can be adopted and those would offer different types of employment and greater rates.

Greg Dalton: You mention that the state level there's been quite a change at the state level impact of the New Democratic Governor, Gretchen Whitmer, who’s either defended or extended statewide clean energy standards. Is that having a positive impact? What’s your take on that, how significant is that?

Guy Williams: Governor Whitmer, for the most part is making a very powerful set of statements in regards to environment and energy for sure. One of the key changes she made early in her administration was restructuring the environmental regulatory agency to include responsibilities for climate change. She also implemented some of the key recommendations from the environmental justice working group that was published last year in the previous administration. So she is making some demonstrative steps that we feel can yield better policy. I mean, I think the key in Michigan though will be elections in the coming year because the legislature is still by and large very hostile to the kind of initiatives we support.

Greg Dalton: There’s a major freeway, I-375 that was built through Paradise Valley historical the African-American community, that's being taken down. What’s your view on that project of removing that freeway that kind of cut through a historic black neighborhood Paradise Valley?

Guy Williams: Well, you know, it's something that arguably never should have happened. And when you look at, through only the lens of logic, more or less putting it back like it was seems like a great idea and maybe it is a good idea. I think the dynamic though that's playing out socially here in the city is it’s adjacent to the downtown. And the likelihood that the same kind of cultural vibrancy that was there before, will not return in that place in that way.

So you can take a cynical view or a more rosy view about how good an idea that is. In terms of climate change and environmental impact certainly to have more walkability to our center city is a good thing. I think what really is important though is that when it comes to major investments and major use of public money that more attention gets paid to areas outside of the center city because the nature of Detroit has so many expansive areas that were primarily residential. Many of those areas are now the density of population is not at all what it was. And there needs to be resources and new attention paid on how to maintain and even strengthen those neighborhoods.

Greg Dalton: So to sum up where Detroit is now in 2019 looking at increased severe storms and perhaps more moderate winters undergoing a pretty dramatic economic change demographic change. How do you feel about the prospects for Detroit for the next five years?

Guy Williams: Well actually I’m very upbeat about it because there are a lot of positive trends. I’m an original founding member of our organization and we started in the mid-90s and at that time the understanding and awareness of the environmental justice issues was not nearly at the level it is today. The mobilization and the sophistication of information exchange is not what it is today. And so I feel that there's growing momentum politically and philosophically that can bring about some positive change.

So for example, having more onshore wind turbines focusing on reducing food waste, expansion of solar farms and regenerative agriculture. All are very viable options either directly in Detroit or in terms of wind turbines, what you have is the opportunity to impact the rates that users of electricity are paying. So that's something that can affect Detroiters very powerfully as well as supporting shutting down the coal-fired power plants.

And so there's places where people are beginning to talk and see the interconnections of different issues. As we plan and be a more strategic as a society, we can make it better. So I’m very, very optimistic.

Greg Dalton: I’m Greg Dalton. On Climate One today we’ve been talking about the future of Miami and Detroit, two cities facing two different climate futures. We just heard from Guy Williams, president and CEO of Detroiters Working for Environmental Justice. My other guests were Miami climate educator Valencia Gunder and Jesse Keenan of the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

Greg Dalton: To hear more Climate One conversations, subscribe to our podcast at our website: climateone.org, where you’ll also find photos, video clips and more. Please help us get people to talk more about climate by giving us a review wherever you get your podcasts.

Greg Dalton: Kelli Pennington directs our audience engagement. Tyler Reed is our producer. Sara-Katherine Coxon is the strategy and content manager. The audio engineers are Mark Kirchner, Justin Norton, and Arnav Gupta. Anny Celsi edited the program. Dr. Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, where our program originates. [pause] I’m Greg Dalton.