Polluting and Providing: The Dirty Energy Dilemma

Guests

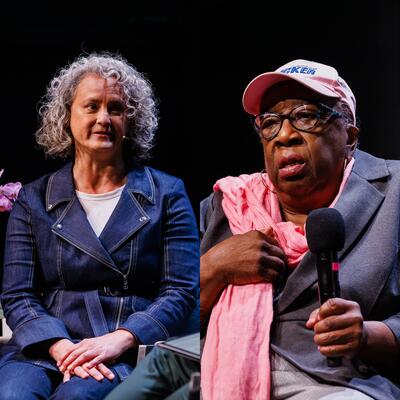

Derrick Hollie

Jacqueline Patterson

Ivan Penn

Vien Truong

Summary

Everyone uses fossil fuels every day. But for many communities of color, that industry is also a source of jobs, tax dollars, and cheap energy.

“Who's going to come to a public hearing and speak out against the utility or oil company that is basically funding their entire budget?” says Ivan Penn, Alternative Energy Reporter for The New York Times. Climate groups, by contrast, find it hard to have the same local influence.

“They’re saying these are things that are bad for your environment, they’re bad for your life and longevity,” says Vien Truong, Director of Climate Justice for the political action committee of former presidential candidate Tom Steyer, “and many people in their communities know that -- there just isn’t an alternative.”

Truong and others are working to make sure that jobs in the clean-energy economy are able to attract workers accustomed to salaries offered by oil and gas companies, especially when retraining is involved.

“How do you retrain a workforce who’s at the golden years almost to the end of retirement,” asks Derrick Hollie, President of Reaching America, a nonprofit he founded that addresses issues facing Black Americans. “Where does that money come from for them?”

To that end, the NAACP has started an initiative called the Black Labor Initiative on Just Transition in order to center the voices of people who stand to lose their livelihoods in the energy transition.

“What are the possibilities -- not just thinking of trading a job [in] coal or oil and gas for another energy job -- but what are the vast possibilities in the new economy that we're trying to transition to,” says Jackie Patterson, Director of Environmental and Climate Justice at the NAACP. “How do we actually really meaningfully and systemically relieve energy poverty that really does put the power in both senses in the hands of the people?”

Additional Interview:

Andres Soto, Richmond Community Organizer, Communities for a Better Environment

Related Links

Communities for a Better Environment

Reaching America

NAACP Environmental and Climate Justice Program

Ivan Penn’s NYTimes Articles

NextGen America

This program was recorded via video on August 11, 2020.

Full Transcript

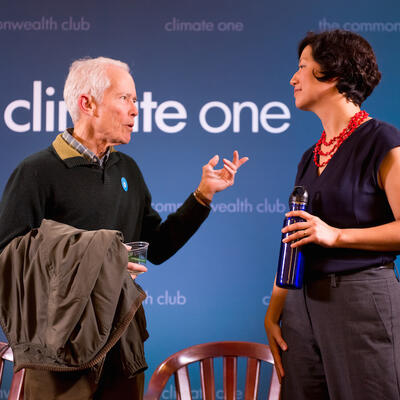

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. [pause] Everyone uses fossil fuels every day. But for many communities of color, the industry is also a source of jobs, tax dollars, and energy.

Ivan Penn: Who's going to come to a public hearing and speak out against the utility or oil company that is basically funding their entire budget?

Greg Dalton: Climate groups find it hard to have the same local influence.

Vien Truong: They’re saying these are things that are bad for your environment, they’re bad for your life and longevity. And many people in their communities know that. There just isn’t an alternative.

Greg Dalton: How can marginalized communities move beyond the fossil fuel economy?

Jacqueline Patterson: What are the possibilities not just thinking of trading or another energy job. But what are the vast possibilities in the new economy that we're trying to transition to.

Greg Dalton: The Dirty Energy Dilemma. Up next on Climate One.

---

Greg Dalton: Are fossil fuel companies community leaders, manipulative greenwashers — or a mix of both? Climate One conversations feature energy companies and environmentalists, Republicans and Democrats, the exciting and the scary aspects of the climate challenge. I’m Greg Dalton.

Greg Dalton: For many Black and brown neighborhoods, some of the biggest providers of jobs, tax dollars, and energy are also some of our biggest polluters.

Jacqueline Patterson: We started the Black Labor Initiative on Just Transition. So that we really make sure that we are centering the voices of people who are standing to lose their livelihoods in this transition.

Greg Dalton: Jackie Patterson is Director of Environmental and Climate Justice at the NAACP. She and many others are aware of how the necessary transition from fossil fuels to clean energy can leave behind many communities of color. But jobs in power plants and refineries pay well.

Vien Truong: What does it look like to make sure that you continue to have the benefits you need, the pension that you had and making sure you have the safety net for your family.

Greg Dalton: Vien Truong is Director of Climate Justice for the political action committee of former presidential candidate Tom Steyer. She’s striving to make sure that jobs in the clean-energy economy, are able to attract workers accustomed to salaries offered by oil and gas companies.

Derrick Hollie: How do you retrain a workforce who’s at the golden years almost to the end of retirement. Where does that money come from for them?

Greg Dalton: Derrick Hollie is President of Reaching America, a nonprofit he founded that addresses issues facing Black Americans, including a changing energy economy.

Ivan Penn: You could have 600 people at a plant whereas a solar farm after it's built, I mean you essentially have a guy with a squeegee.

Greg Dalton: Ivan Penn is an Energy Reporter for the New York Times. Earlier this year he wrote about Adora Nweze [n-WAY-say], the president of the NAACP's Florida Conference. In 2014 she wrote an op-ed in the Tallahassee Democrat opposing a rooftop solar rebate. Penn reported that several months later the NAACP issued an invoice to Florida's largest utility for $50,000.

Ivan Penn: Some of the work that the NAACP has been doing in recent years highlighted the fact that the effects of climate change on Floridians were significant enough to reevaluate the Florida State Conference’s support of the utility industry which had been funding the state conference a great deal tens of thousands of dollars. And in general what have been happening even during regulatory meetings was that the NAACP would typically support the positions of the utility companies. Generally arguing that some of the policies that were pro-renewable pro-energy efficiency raise questions about the impact on communities of color on the disadvantaged. They seemed more benefits in the purview of the wealthy who could afford solar panels who could afford Energy Star appliances who could afford to weatherize their homes, leaving the disadvantaged to pay the cost of the electric grid. While those who could more afford it were reducing how much they had to pay to the utility. And so what we saw and what we reported in this story was Adora Nweze came forward and said, hey, you know, I realized after a study that the NAACP had done that there were severe negative impacts on the communities of color in Florida which obviously you have significant concerns in Florida between the hurricanes sea level rise and flooding. And she recognized that they had to do something different and she shared that story with us.

Greg Dalton: Jackie Patterson other chapters of the NAACP had similar postures in 2017. Ivan reported the Illinois chapter also opposed solar power and stronger energy efficiency measures in 2018 NAACP's top executive in California signed a letter opposing renewable energy. Paint the picture for us this broader pattern of these communities of color in relation to the energy companies who often are very close to them.

Jacqueline Patterson: Yeah, thank you. In many cases what we’re finding with the NAACP leadership is a concern around the negative impacts of making the shift. As Ivan said the analysis around people having to pay higher bills for their electricity people losing jobs and so forth. And the NAACP knowing that this nation was built on regressive policy the disproportionally negatively impact to us it was fairly easy for the fossil fuel companies to really paint a fairly myopic picture of the negative impacts that made our NAACP leader say okay yet again here is another situation where it's advantage in people with wealth at the expense of our communities. And so that is the fertile ground on which the seeds of doubt were planted that resulted in some of these positions.

Greg Dalton: Chevron's oil refinery in Richmond, California, it was built before the surrounding city even existed. And for a long time there wasn't much pushback from residents of this company town. But over the past two decades, the community has challenged Chevron in no small part due to the work of activist and longtime resident Andres Soto. Climate One’s Andrew Stelzer spoke with Soto about growing up in the shadow of big oil.

[Start Playback]

Andrew Stelzer: Andres Soto was a baby when his family moved from Berkeley to Richmond, California in the late 1950s. At that time Chevron's oil refinery had already been in operation for over five decades. Soto says it was an unquestioned part of the landscape.

Andres Soto: As a child no one ever spoke about not having them. No one ever spoke about trying to control over their pollution. People weren't connecting that with health outcomes and health experiences. And, you know, I went to Richmond high school where the mascot was the Oilers, you know, we had an oil can guy on the side of the football field. And then I began to understand the role of Chevron in the politics and the economy of the community. In my family all of us, my parents, my siblings we’ve all gotten adult onset psoriasis. I had a brother who died of brain cancer month before his third birthday when I was seven years old, I’m the oldest. My other brother got cancer of his tongue when he was in his 30s. So, you know, we can't prove in court it was Chevron but I grew up my entire childhood being about 2 miles downwind from the refinery with all those experiences prior to regulations to clean it up.

Andrew Stelzer: In 2004 Soto ran for Richmond City Council as one of the founders of a new group called the Richmond Progressive Alliance. RPA's candidates were fierce critics of the pollution caused by Chevron's oil refinery. Although Soto narrowly lost the RPA won two other local races and Chevron begin funding the RPA's opponents.

Andres Soto: And then there was the notorious 2014 election, where they spent $3.5 million dollars in the election and all their candidates lost. After that they went back to the drawing board and started doing a softer approach. And so they've been making contributions to more community organizations and buying their loyalty for their projects. They started their own online news service and they have a permanent news service called the Richmond Standard. And they choose the content so it’s propaganda organ for them.

Andrew Stelzer: Soto's ultimate goal is the decommissioning of the Chevron refinery and he says other energy producing communities across the country should try and develop economic transition plans so that they can one day do the same.

Andres Soto: Having a large industrial facility in your community, whether it's an oil refinery or a steel mill or a smelter or any, you know, cement plant. It is going to bring revenue, but there has to be a different way of evaluating cost-benefit. When you start adding up all those chips the cost of healthcare the loss of productivity the loss of life expectancy increased poverty of people who grow up along the fence line of these facilities versus the amount of income that is brought in through taxation. It then starts to become a different kind of the equation. It’s just no longer good enough to look at it from dollars and cents. We also need to look at it from the health of the planet.

[End Playback}

Greg Dalton: That was Andre Soto, an organizer with the Richmond California branch of Communities for a Better Environment. Derrick Hollie, I’d like to have your response there to his comments about balancing the economic and human health benefits of large energy facilities.

Derrick Hollie: A couple of things. One, I think it’s very unfortunate the things that happened to his family. And I also think it’s unfortunate that they are not able to prove or associate Chevron with where he want it as a place for his family. One of the issues that, you know, Greg, and we work on mostly is energy poverty. Energy poverty occurs when individuals aren’t able to afford just basic heating and electric needs. And I think the technology over the years has changed a lot. I think he said it’s been five decades since that power plant was built prior to the community being built. Who knows what went into that facility prior to, you know, when it’s first built. Again, the technology has changed a lot it probably has a lot of the old systems in place and we still don’t know the effects of it. But I think there’s a balance that we have to have in terms of our approach towards energy and development and being good stewards of the environment. And I would point to Port Fourchon down in Louisiana, I had an opportunity to visit Port Fourchon, Louisiana a couple years ago and this is where they have all the onshore operations for all the offshore operations that take place for BP, Shell, all the big oil companies. And it’s just interesting because people travel from around the world will to study the gulf because it’s so rich in fish and wildlife. And I think again, and I’m a licensed captain, I love the water, took my boat from Maryland to Florida and I’m a true steward of the environment. But I think we got to find that balance between our energy development, production and keeping the environment safe.

Greg Dalton: Vien Truong, your take on what Andre Soto was talking about in terms of the softer approach that Chevron has taken in Richmond. There’s a well-told story about handing out backpacks for kids to go to school and being well received by the company there. Perhaps in some ways better than some of the environmental groups.

Vien Truong: Right. You know as you said earlier Richmond’s refinery has been there for a long time and many people went there to get the jobs and it was considered a company town. And as part of their working building their communities they were doing some of the, you know, work with building relationships including these backpacks. What we haven't seen is the corollary with a lot of climate groups. They’re coming in there and they’re saying these are things that are bad for your environment they’re bad for your life and longevity, and that’s true. And many people in their communities know that there just isn’t an alternative. So what we often do is what we have not learn to do well is to go from protest to actually creating solutions. How do we offer an alternative how do we actually invest in the communities to actually give and create more jobs. How do we build the inroads, you know, when we hear about organizations that respond against the increase in utility cost because it will actually hurt the low income ratepayers even more that makes a whole lot of sense to me. We’re in a place in America right now where most families don't have $500 in their savings account before COVID. And now when you look at what’s happening the restoration of our healthcare systems the lack of ability for people to have their own social safety net. We don’t have retirement savings in many of our communities. The cost of living in California is so high we’re seeing cities across the street from where we live. And so when you talk about increasing the cost of energy which is fundamental for survival especially during these days of course it make sense for us to respond in kind. What I would say though is that it shouldn’t be seen as post economy it shouldn’t be either or. What the organization should have done in the first place is to go to the communities to discuss what are the right solutions and how do we work together to actually create a better solution. And had they done that they would have realized that there is a better way to actually be more nuance in creating policies which I think is what we’re learning to do now. So I’m glad that now we’re beginning to talk about these incidents in case studies where we begin to create an option for us to actually build better relationships to actually work together with stakeholders. So that we’re not making a false choice between our environment and our economy.

Greg Dalton: Jackie Patterson, so when economies like Richmond, California try to diversify oftentimes there’s questions of displacement or gentrification that are very painful when a company like Richmond tries to diversify away from just the oil refinery and they have a big university research center a ferry terminal with some housing. Then the communities like hey we’re getting priced out of here. So how do they grow out of it, you know, diversifying grow out without hurting the people who were there?

Jacqueline Patterson: Yes, you can imagine it's one of many committees that are facing the same challenges. And actually if our annual convention have moved forward this year although it's happening a little bit later. Our workshop was going to focus on this whole issue of gentrification displacement. And how do we grow and have community improvement without community displacement. And so we have been putting together a suite of ordinances that could be put in place to help mitigate against the displacement that happened. And based on some of the practices where people have been successful in doing community improvement without displacing communities. So we're still digging deep on that research so that we can really put forward those models. But it is possible to do but the important thing is making sure that communities are in the driver seat so that the improvement isn’t something that happens to them and therefore the displacement being more likely if they’re driving it and know what measures they can put in place to prevent displacement then we’ll most likely gonna have a win-win situation.

---

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation about the dirty energy dilemma. Coming up, navigating the power dynamics on both sides of the energy divide.

Ivan Penn: The big question is, where's the grown up in the room that should be the regulators and the government to help the consumer to navigate the push by these different industries that are trying to win their dollars.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

---

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton, and we’re talking about how fossil fuel companies relate to communities near their refineries and power plants. My guests are Derrick Hollie, President and founder of Reaching America. Jackie Patterson, Director of the Environmental and Climate Justice at the NAACP. Ivan Penn, Energy Reporter with the New York Times. And Vien Truong, Director of Climate Justice for a Political Action Committee run by Tom Steyer, a climate activist and former Democratic presidential candidate. The 2016 Democratic presidential nominee, Hillary Clinton, offered a $30 billion plan to help coal workers that was focused on retraining – an idea invoked frequently in the clean-energy transition. I asked Vien, who’s been involved in green jobs for more than a decade, whether that retraining ever really happens.

Vien Truong: Does it really happen? Sure, in different pockets and specificity. I think what I would look back at the 30 billion is it needed to be unpacked about where was the money going to be spent and how this transition was going to work with a lot more specificity needed and making sure that we’re working with people who are in those industries to look at what is a real rational plan. That's not very abstract, that’s linking at, you know, for folks who are in older tiers ready to retire what is that look like for the transition, right. What does it look like to make sure that you continue to have the benefits you need the pension that you had and making sure you have the safety net for your family. And oftentimes, you know, previously there was a single person household that’s carrying the weight, economic weight of the whole family on this one income and making sure that the family is protected. And if people are kind of in the middle tier, how do we make sure that they have the right skillset. What kind of industries do they have in the nearby vicinity that they can actually get connected to with the reasonably level, amount of wages and the same kind of corresponding benefits. And then for the younger folks, how do we make sure that we’re continuing to get them kind of directed at cleaner jobs or better jobs. And how do we make sure that the whole of the community actually have other options and economic diversity for other places to work besides just your fossil fuel industries. And that’s where I think the 30 billion could have been better unpacked and kind of brought in folks who are proximate to the problem or proximate to what’s going on to help design the solutions. And I think that’s the learning lesson that we have here. How do we make sure that, you know, whether you’re working at a very local level or the federal level that we don’t do things in a vacuum or in silos. We are now more interconnected than ever before. We have to start bringing in folks to help make sure that we’re creating solutions that makes sense for everybody, right. You can’t create solutions I mean for a long time, you know, my family is refugee folks from Vietnam. For a long time policy is done to people and not with people. And now we’re at a place where we understand that we have to make sure that we are not only creating a seat at a table for people who are approximate to the problem but bring the table to the community that you’re trying to create policies that actually effects. And make sure that they’re co-creating the solutions with the policymakers with those different folks who are actually helping to shape the future so that we can design something that makes sense with all the stakeholders involved.

Greg Dalton: Ivan Penn, I’d like to talk to you about, you know, this jobs transition people hear about that like, you know, what are coal miners going to do. But the jobs in clean energy are very different types of jobs often in a very different place.

Ivan Penn: That’s right. And you're talking about a significant difference in pay where you are going from nuclear jobs, which are obviously very high paying jobs, a reactor you could have 600 people at a plant whereas a solar farm after it's built, I mean you essentially have a guy with a squeegee. And so I mean those are real issues. You have a lot of jobs created in the development and installation of solar and wind but you don't have as many as the fossil fuel and other big-box power plants. There is a lot of training that companies have been providing in this transition. But I recently wrote a story about some of the competition between renewables and natural gas now. And there was a power plant closed in North Dakota, Underwood, North Dakota and the utility was switching to wind and natural gas from coal. That is a devastating decision to the small town there that depended on not only the power plant but also the coal mine that supplied that power plant. And now that town is wondering what are we gonna do and other nearby small towns. So there are some real issues and the question is how does the country navigate the transition that increasingly all parties are embracing in order to deal with climate change.

Greg Dalton: Jackie Patterson, I was an Internet reporter in the early days of the Internet and the thinking then was that it was good to democratize information that there were gonna be so many sources of information lots of competition this sort of moving away from centralization of IBM and mainframe computers. Now we have a situation where a handful of large companies dominate the Internet that democratization didn't happen. And I hear similar that echoes for me similar conversations about distributed powers gonna be more democratic and people, you know, power to the people from their rooftops. I’d like to hear your thoughts on, kind of the concentration and distribution of power as we move from a fossil economy to a cleaner economy. We might have a replay the same kind of same story.

Jacqueline Patterson: Yeah, that is kind of to the some of the points that are being made before we started this initiative called the Black Labor Initiative on Just Transition. So that we really make sure that we are centering the voices of people who are standing to lose their livelihoods in this transition. And in that conversation with the black labor folks in the lead we've been talking about how currently the centralized power has resulted in circumstances such as the 76,000 coal miners that have lost their lives since 1968 while the National Mining Association, which consisted of the very companies that employ them fought against the regulations to be able to protect them from the coal mine dust that is tied to the black lung disease that took their lives and that's and counting. And so we've talked about how not only is there lobbying against those types of regulations, but it's also a number of these fossil fuel companies are paying into groups like ALEC that push forward on everything from school on prison privatization to water privatization to even voter suppression laws. And so that centralization of power and the lack of real people engagement and what is in that agenda. And for our communities it’s at the expense of the well-being of our communities points to us for the need of decentralized and the wealth and the power that’s driving that machine. And so for us in the content of the conversation with the Black Labor Initiative it's really talking about how do we, what are the possibilities not just thinking of trading a job and doing coal or oil and gas for another energy job or even. But what are the vast possibilities in the new economy that we're trying to transition to. And so and in each of the sectors of this new economy we have a lot of folks who are pushing for decentralization because whether it's people getting their electricity shut off for nonpayment while the company that’s, you know, responsible for it has a CEO making $9.8 million a year and you’re cutting somebody off for $60 literally at the cost of their lives. I report lights out and Nicole talked about people who are burning candles for electricity after having their, I mean for light after having their electricity cut off and burn down their houses. So they literally paid the price of poverty with their lives. And so to this point around energy poverty we are really looking at and how do we actually really meaningfully and systemically relieve energy poverty that really does but the power in both senses in the hands of the people.

Greg Dalton: If you’re just joining us we’re talking about fossil fuel communities and communities of color with Jackie Patterson, Director of Environmental and Climate Justice at the NAACP. Derrick Hollie, President of Reaching America. Ivan Penn is Energy Reporter with the New York Times and Vien Truong, Director of Climate Justice for the Tom Steyer PAC. Derrick Hollie, your grandfather was a coal miner. And lot of your writings you cite the Heritage Foundation as an authoritative source. I wonder what you think about the prospect of coal in America. Is it gonna come back as Donald Trump claims?

Derrick Hollie: No. I don’t think there’s gonna be a comeback with the coal. I just don’t, for a couple different reasons. One, as we talk about coal I watched it because my grandfather was a black coal miner in Southwest Virginia. And I’m seeing right now coal represents about 28%, 29% of our entire energy mix. And I’ve seen a decline over the years when I started this thing Reaching America five or six years ago, coal was at like 34%, 35%. And just in five, six years it’s gone down to 29%, 28%. And I think we’re gonna continue to see that decrease in coal for one reason. One because natural gas is cleaner, is more efficient, we have in abundance. And so while I think coal will continue to decrease in terms of our electric mix and the energy supply goes, I think coal will always be around because we still gonna need it for different materials, i.e. windmills, solar panels and that kind of thing that will still keep coal in place but not to the level where it is right now. But also, I wanted to just also if I could at just with the loss of the jobs that we’re just talking about. I had the opportunity to go back to Southwest Virginia and visit where my grandfather was a coal miner. And that area still, 50 years later, has never rebounded. And you talk about poverty in the Appalachia it is so different from that in an urban city. Like I said I lost count of the number of homes the roofs were damaged. And these had a blue tarp on the top with tires holding it down because they couldn’t afford get their roofs fixed. And probably like since ranch are rapid in Appalachia is because the loss of the coal mines there. And they tried to replace some of those jobs by opening prisons, that’s not the answer either. But it’s gonna be very difficult as we continue with some of these proposals that are being put forth right now that are trying to eliminate oil and gas jobs and just wonder as then were saying, how do you retrain a workforce who’s at the golden years almost to the end of retirement. Where does that money come from for them? And so that’s why we just need to hold on pump our brakes as we transition to renewables just to make sure that everyone is taken care of in our effort as we continue to do that.

Greg Dalton: As we continue our conversation about communities of color and fossil fuel facilities around America. We’re gonna go to our lightning round on Climate One. I’m gonna ask each of you a true or false question. Just one word first, you know, true or false and then we’ll go to association. So beginning with Derrick Hollie. True or false, café standards for American cars and trucks were flat for nearly 25 years from 1985 to 2009 when President Obama proposed a 5% annual increase, true or false?

Derrick Hollie: True.

Greg Dalton: Flat for 25 years. True or false. Jacqueline Patterson, fossil fuels have lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty?

Jacqueline Patterson: Hundreds of millions. False.

Greg Dalton: Derrick Hollie. True or false, fossil fuel companies place refineries and power plants in neighborhoods populated by people of color?

Derrick Hollie: Is this a true or false question?

Greg Dalton: True or false.

Derrick Hollie: I would say in the past, yes, true, absolutely.

Greg Dalton: Also follow up true or false, because those people have less political power?

Derrick Hollie: So I would say, yes, true.

Greg Dalton: Ivan Penn. True or false, Wall Street prefers solar energy on residential rooftops rather than industrial installations?

Ivan Penn: False.

Greg Dalton: Vien Truong. True or false, climate philanthropy in this country is dominated by a handful of billionaire white men names such as Bloomberg, Steyer, Simons Grantham and others?

Vien Truong: Quasi-true. Here’s why. I mean I work for one of those guys. There’s so many more foundations and family foundations and people that are coming up and actually doing the work. And so that misses the amazing work that so many other people are actually doing. So, in that case there’s some folks getting all the attention but it actually is being done by a bunch of other folks.

Greg Dalton: Once again you have the white guys get the attention. Okay, true or false. Ivan Penn, Duke Energy compelled one Florida homeowner to buy a million-dollar insurance policy because it said the solar panels on his home could harm the electric grid?

Ivan Penn: That would be true.

Greg Dalton: Vien Truong. True or false, Wall Street likes cap and trade because they can game it?

Vien Truong: True.

Greg Dalton: Derrick Hollie. True or false, you have received direct or indirect funding from fossil fuel interests?

Derrick Hollie: True.

Greg Dalton: This is an association, I’m just gonna mention something and ask you to think of the first thing that pops in your mind off the top of your head with reckless abandon. Jackie Patterson, what’s the first thing that comes to mind when I say green jobs

Jacqueline Patterson: Greenwashing.

Greg Dalton: Also Jackie Patterson, what’s the first thing that comes to mind when I say the U.S. Chamber of Commerce's position on climate change policy?

Jacqueline Patterson: I would say hopefully evolving.

Greg Dalton: Ivan Penn, what’s the first thing that comes to mind when I say Florida Power & Light?

Ivan Penn: Influential.

Greg Dalton: Also Ivan Penn, what’s the first thing that comes to mind, top of mind when I say Florida Governor Ron DeSantis?

Ivan Penn: Current governor

Greg Dalton: That was a dodge. Okay. Vien Truong, what’s the first thing that comes to mind when I say all lives matter? Also, Vien Truong, what’s the first thing that comes to mind when I say Mount Rushmore

Greg Dalton: Derrick Hollie, first thing that comes to mind when I say voter fraud?

Derrick Hollie: November. I think of November, the election

Greg Dalton: Last one, Derrick Hollie, what’s the first thing that comes to mind when I say Donald Trump?

Derrick Hollie: Whoa! That’s what comes to mind, whoa!

---

Greg Dalton: You're listening to a conversation about race, power, ,and fossil fuels. This is Climate One. Coming up, connecting covid, climate and the wider economy.

Vien Truong: Most of these small businesses were actually led by people of color. Most of them actually hired from the community are reinvesting back into the economy. So when we’re not actually creating a safeguard for these industries we’re actually gonna see an even bigger gap between the haves and the have-nots.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

---

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. We’re talking about energy and power in communities of color with Jackie Patterson, Director of the Environmental and Climate Justice at the NAACP. Derrick Hollie, President and founder of Reaching America. Vien Truong, Director of Climate Justice for Tom Steyer’s PAC. And Ivan Penn, Energy Reporter with the New York Times. The fossil fuel industry is complex but power is highly concentrated. For gasoline and jet fuel, a small number of oil companies dominate. On the electricity side, most people have little choice but to buy from a local monopoly. I asked Ivan whether there’s a similar concentration of power among clean-energy companies.

Ivan Penn: Well, obviously when you have a younger industry. So not the same level of influence. You do have a consolidation of power through the associations. On the solar side the major one is the solar energy industry association. And it's made up of all of the solar players so you have a mix there where it's the utilities it’s the industrial commercial installer those who get it installed in industrial commercial sites. And then there’s the rooftop solar businesses that are installing in residences and all. So that becomes a significant voice because of the numbers of players that are working together. The Wind Association, you know, is a significant voice with all of the onshore and now the developing offshore wind. And then when you combine those voices in the course of growing storage industry. When you combine those voices together it becomes a significant block. But the dynamics are very, very different for the renewables and we talk about the and the voice of the consumer as opposed to the energy industry which has organizations that are unified nationally and even internationally. And they have a narrative and a script that the renewable side is beginning to develop the consumers are much more fragmented and don't have the same kind of voice that either one of these parties do. And are trying to navigate the push and the lobbying from each one of these industries. And at the end of the day the big question is, you know, where's the grown up in the room that should be the regulators and the government to help the consumer to navigate to push especially in a capitalist society by these different industries that are trying to win their dollars. And so even though I mean you have the bigger voice of the oil, natural gas utility industries versus the growing renewable sector. There's the masses though are, you know, caught in this place of not having the kind of voice that they need so that they can make informed decisions about both their government and their lives.

Greg Dalton: Derrick Hollie, you seem to be right of center politically, you know your thought on where government is in terms of regulating the energy industry in this country. Because I know a lot of conservatives who don't like the idea of monopolies they want market competition. Your thoughts on sort of the power structure of energy and how the government is overseeing that sector?

Derrick Hollie: Well, I think a lot of times again it's the general public they don't have a voice and I think a lot of times they are misled by both sides. And I’d say that, you know, the oil and gas what from what I sit, the oil and gas is actually -- I think they need to do a better job of informing the public of what they do, the uses of fossil fuels and et cetera. Meanwhile, from where I sit, the environmental groups aren’t in the Sierra Club they are bombarding people, telling people that it’s so bad. Natural gas is bad. Everything that is fossil fuel is bad. Keep it in the ground, don’t pull it up. All those kinds of things. So people right now are just like, oh my god, and it’s coming down to who they even vote for in the November election. Is it gonna be New Green Deal with Joe Biden? Or is it gonna be, you know, fossil fuels with President Trump? And so, and the thing about it is like again misleading the people because on the side with Joe Biden, I know most of those people, black people in particular are not in the market to buy an electric vehicle. But meanwhile with that policy they’re putting now and with the direction of a Joe Biden, that’s what you’re gonna be, you’re gonna have to do that. And I don’t think people really, really understand when it comes to policy and the politics involved when it comes to energy. Because both people, both the left, the right, the environmental groups the oil and gas industry they’re just throwing so much at people it’s just hard to decide for what’s best for them.

Greg Dalton: Jackie, I’d like to go to you and you have a pamphlet from the NAACP, top 10 manipulation tactics of fossil fuel companies. And particularly there's three of them there about exaggerating the level of job creation, pacify or co-opt community leaders and praising false solutions. Tell us a little bit about some of those tactics that you see on the part of fossil fuel companies.

Jacqueline Patterson: Sure. So whether it’s the Keystone pipeline or it is even some of the other coal plants that are being built in communities or otherwise that often there will be promise of jobs but not really the kind of specificity that these are only construction jobs that are only gonna last so long or there’s gonna be jobs coming into the community but were also bringing people who already have those jobs. So those are the kind of things that we're finding in different places where the promises don't actually match the reality. So then in terms of attempting to pacify or co-op communities it is definitely whether it’s the -- so it’s one thing sometimes some of the companies will say that they just wanting to be a good neighbor in terms of providing financial support to communities which is how some of our community say, oh great, they want to be a good neighbor and so that’s fair we’ll take that. And then there is the times like President Nweze talked about and others how they will tie those financial contributions to the communities supporting their position very explicitly. In the report we talked about the St. Louis NAACP talked about how they were receiving funds every year then one year they said, oh we didn't get our check this year for our Freedom Fund Banquet, we’re just, you know, checking out just to make sure didn’t get lost in the mail or something. And they said, oh, you know, we give money, yes, we give money to our friends but your people went and testified at the EPA hearing on recreating their toxics therefore, you are no longer in the friend category. So the check was not indeed lost in the mail it never was sent out. And so these are the kind of things where it’s starting to be revealed the basis of some of these relationships.

Greg Dalton: Ivan Penn, you cited a study that said from 2013 to 2017, 10 of the country's largest utilities gave out about $1 billion in donations. Where does that money go what the companies get for those donations to community nonprofits?

Ivan Penn: Well, I mean it’s a variety of places. So everything from your non-profit organizations the NAACP the YMCA the Boys and Girls Clubs and arts events which are getting their names put on performing arts centers and parks. And I remember a State Senator in Florida said that they saw in that particular case Duke Energy is just a good public citizen to the state of Florida and didn't realize some of the issues that were there because there was a particular problem with a broken nuclear plant that ended up costing consumers hundreds of millions of dollars. And they were charging in advance for another plant and that cost consumers a billion and a half. And so when the senator looked at it all he was like, well, you know, because of all the things that they do in the community, you know, we saw them as a good corporate citizen. And then it makes it difficult for, I mean who's going to come to a public hearing and speak out against the entity whichever one it is whether it's utility and oil company natural gas company that is basically funding their entire budget essentially. I mean because it doesn't have to be a whole a lot of money for a nonprofit to have their entire budget funded. And then it's a drop in the bucket for, you know, corporations of the sizes of the utilities and oil companies. It makes it difficult for anyone to speak out against the hand that’s feeding them. regulators

Greg Dalton: Vien Truong, I wanna talk about, we’re talking about the energy transition. We have to talk about unions often thought as, you know, support on the left but they support a lot of the pipelines that are proposed around the country, a lot of fossil fuel infrastructure. Where are unions on this transition are they also kind of holding to those well-paying fossil fuel jobs because a lot of renewable energy jobs are not unionized.

Vien Truong: Yeah, I think what we wanna unpack first is that it conflate the jobs with their kind of position on climate. Because really when they're looking at what these projects are they’re looking at what the jobs and the job quality tied around these projects. And I want to maybe dig a little bit, dig deeper on that. Because what we know and maybe too often conflate is the interconnection between cheap labor and the rising CO2 emissions, right. It’s the same logic that is driving for maximum profit that is using kind of unsavory tactics from paying people to testify and support a projects to maximizing profit by any means necessary including making sure that there are working labors for pennies, burning of coal, you know, blowing out mountaintops to get to the coal. The underlying logic of by any means necessary we’re going to get our profits, we’re gonna get, you know, these projects moving forward. And for us when we’re doing this work we have to make sure we’re looking at the interconnections of investing in communities investing in good jobs and making sure that we’re not putting sacrifice zones, you know, that we’re not sacrificing people in lieu of making the jobs real. So for me, you know, that highlights a responsibility for us then to make sure that we’re actually not only doubling down in creating the clean energy jobs but making sure that those jobs are actually as good and pays good wages they actually reflect the standard of living and the standard of pay that we have to get people to and we create wraparound benefits around that. Then we have to make sure that there's a pipeline into those good jobs for communities across the board.

Greg Dalton: Jackie Patterson, as we get to the end here, I want to make sure that we connect the COVID vulnerability we know that African-Americans have higher incidence of asthma they're more vulnerable to COVID they’re likely to be living in these fence line communities. So how is that impacting, I wanna make sure we hit that.

Jacqueline Patterson: Yeah, so many ways. One, we certainly have seen the Harvard study that ties PM 2.5 which is particulate matter to COVID says that indicates that COVID actually rides on these particulate matter particles. And we know that those the particular matter is much higher in black communities in particular from sources including any type of burning whether, you know, combustion whether it's the coal plants or through car engines or through burning of incinerators and so forth. So that is certainly there plus as you said the history of having compromise lung capacity from being near roadway air pollution and so forth and so on. It means that we’re more vulnerable to COVID-19 which impacts the lungs. So all those different ways. And then on top of it all, if we are less mobile in terms of having individual cars then in order to whether to get to places to get food or do the essential work because we’re likely to be essential workers it means that we’re the ones who are getting on these buses where there's more likely to be transmission. Time and time again you hear people talk about how it’s so much safer riding in your individual cars and many of us don't even have that choice. And so there's so many intersections there. So I’ll stop there.

Greg Dalton: Vien Truong.

Vien Truong: You know I think it's really important when we see the protest that are happening now across the country. It makes so much sense to me that anger is justified. We are facing the economic injustice the racial injustice environmental injustice that this pandemic has really revealed to this country, right. We’re seeing a breakdown of our institution that is supposed to keep us safe from hospitals to energy to housing those things are crumbling. We’re seeing people who with the end of a moratorium and evictions we’re seeing people being displaced in mass. And on top of it all, we’re seeing the PPP funds and loans that are supposed to going to help protect people the emergency support it's going to actually the wealthier folks, right. Jared Kushner’s friends gotten a ton of PPP loans the folks who did not get the loans though, 90% of small business did not get PPP loans. And when you look in California alone most of the small restaurants, most of the nail salons, most of the service industry they are people who are primarily most of these small businesses were actually led by people of color. Most of them actually hired from the community actually reinvesting back into the economy. So when we’re not actually creating a safeguard for these industries we’re actually gonna see an even bigger gap between the have and the have not. And then to make that even worst we’re looking at the digital divide where students are now being asked to learn remotely when a lot of families don’t even have Wi-Fi or laptops at home. And so we’re gonna see this wealth inequality continue to get even worse if we don't do something about it. So I’d say we got to take a look now and making sure that this reveal that we’ve seen with the pandemic actually forces us to focus on investing in the communities that are the front lines that are in the sacrifice zones and make those our sacred work right now.

Derrick Hollie: Amen.

Greg Dalton: We have to wrap up. Derrick Hollie, I saw you nodding, yes, to a lot of that?

Derrick Hollie: Yeah, I was just saying, amen to that. She said it all. She said it all. And we have to look at right now what COVID has done to this country. It has in many ways pull back the covers on all of our dirty secrets and things that are wrong in this country. And I’m thinking in order for us to cross this right now, we’re gonna all come together. Can’t be no left, can’t be no right, can’t be no white and black this is American issue right now. If you look at what’s going on it’ll be hard to say that there is unity right now on this country. And I think we’re gonna have to get past this divide that exists before we can pull ourselves out of this situation that we’re in right now.

---

Greg Dalton: We’ve been talking about the dirty energy dilemma for communities of color with Derrick Hollie, President and founder of Reaching America. Jackie Patterson, Director of the Environmental and Climate Justice at the NAACP. Ivan Penn, Energy Reporter with the New York Times. And Vien Truong, Director of Climate Justice for Tom Steyer’s PAC.

Greg Dalton: To hear more Climate One conversations, subscribe to our podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you get your pods. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. It really does help more people find us.

Greg Dalton: Kelli Pennington directs our audience engagement. Tyler Reed is our producer. Sara-Katherine Coxon is the strategy and content manager. Steve Fox is director of advancement. Devon Strolovitch edited the program. Our audio team is Mark Kirchner, Arnav Gupta, and Andrew Stelzer. Dr. Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, where our program originates. [pause] I’m Greg Dalton.