No Going Back: EVs and Clean Tech Tipping Points with Albert Cheung

Guests

Albert Cheung

Summary

In the tech world, there’s a common belief that once a new device hits 5% market penetration, it rapidly goes from fad to mass adoption. Think of smartphones, social media, or even the personal computer. According to Bloomberg, the US has just passed that critical 5% tipping point for new EV purchases. Norway, an oil-rich country, was first to hit that 5% mark in 2013 and today boasts a stunning 86% of new cars being fully electric.

We know that the US market has very different needs and attitudes than Norway. But we’ve seen significant market growth of EVs after hitting the 5% mark in other countries as well. According to Albert Cheung, Head of Global Analysis for BloombergNEF, “The UK is a big broader-based economy and it didn't have such a huge tax break freebie as Norway did. So, what happened in the UK was it took about five years to get to 1% EV sales that happened at the beginning of 2015…It took about another five years to get to 5% and that was the end of 2019…One year after that we were at 18% and another year after that we were 33%.”

China is also seeing dramatic growth of EV market share. Cheung says, “China is now well past that tipping point and the same thing has happened there. And so, what do these markets have in common where we’ve seen that happen? All these markets have strong policy support both on the supply side and the demand side. So, they have fleetwide CO2 targets that automakers have to meet, which means they have to bring EVs to market. There are demand side subsidies to subsidize the purchase for the end-user. And that seems to be a formula that is working. It works in Europe; it works in China.”

Just as important, Cheung explains, is that automakers supply the market with choices that consumers want. “One of the things that is an absolutely critical factor for that tipping point to take off is that the models have to be available. You need to have a wide choice of vehicles that fit your needs. Whether you want to buy an SUV or a pickup truck or a city car or family van, whatever it is. You need that range of models to choose from and need automakers to be building them in these types of numbers that can really support the market.”

But what does it take to manufacturers to commit to entering new markets?“It's all about creating that policy environment where there’s confidence for the automakers to invest,” says Cheung. “Recently we saw Ford come forward with its $50 billion EV plan which really just gives me a lot of confidence that we are gonna see that mass-market option in the US in the next few years.”

There is a segment of EVs that is often overlooked: mircomobility vehicles. E-bikes, e-scooters, e-mopeds, any electric vehicle with 2 or 3 wheels. According to Chase Stubblefield, Managing Director at Electric Scooter Guide, “There is so much organic momentum behind micro mobility. Even without the regulation, without the space, without a medium speed lane or slow speed lanes, it's still thriving and growing 10 X instantly.”

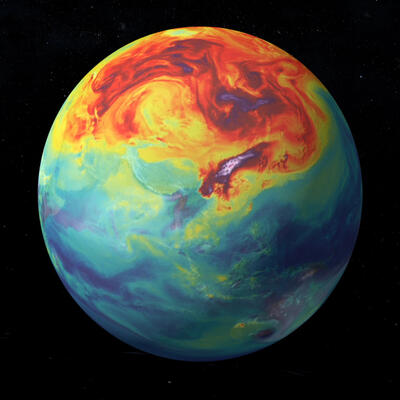

When it comes to renewable electricity, Albert Cheung believes we are already well past the 5% tipping point, particularly when focusing on new installation: ”If you look at all of the power capacity that's added each year, about two thirds are wind or solar. About 80% of it is clean, is renewables.”

Related Links:

BloombergNEF Electric Vehicle Outlook

US Crosses the Electric-Car Tipping Point for Mass Adoption

Electric Scooter Guide

EV Adoption Barriers

Full Transcript

Note: Transcripts are generated using a combination of automated software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the actual audio before quoting it.

Greg Dalton: In the tech world, there’s a common belief that once a new device hits 5% market penetration, it rapidly goes from a niche to mass adoption. Think of smartphones, social media, or even the personal computer. Could the same be true of the green tech we need to prevent the most dire climate catastrophe? According to Bloomberg, the US has just passed that critical 5% tipping point for new EV purchases. Norway, an oil rich country, was first to hit that 5% mark in 2013 and today boasts a stunning 86% of new cars being fully electric. Now California is driving the US along a similar road away from gasoline and diesel. The state just passed a new law that will only allow emission free vehicles to be sold by 2035. Washington, Massachusetts, Virginia and other states are poised to follow. Even with that California law, how confident can we be that all new American cars will be running clean? Albert Cheung is the Head of Global Analysis for BloombergNEF. I asked him about the Bloomberg tipping point story.

Albert Cheung: Yeah, and this an article that my colleague Tom Randall from Bloomberg News wrote using the data collected by my team in BNEF. And he makes this assertion that once a market hits 5% EV sales, then that's the tipping point and everything is going to go from there and you’re gonna see a huge scale up. And it's really interesting so I actually look into the data myself just to see, you know, because it’s our data as well. you could argue, you know, the tipping point is 1% or 10% or whatever. So, I look at the UK because the UK's a big it's a broad-based economy it’s not Norway because everybody talks about Norway all the time but not every was Norway. And the UK is a big broader-based economy and it didn't have such a huge tax break freebie as Norway did. So, what happened in the UK was it took about five years to get to 1% EV sales that happened at the beginning of 2015. So, Q1 2015 roughly 5 years off to the start of EV sales. You can debate whether EV sales started in 10 whatever roughly 5 years. It took about another five years to get to 5% and that was the end of 2019. And actually, it never even got close to 5% until that point, Q4 2019 it got to 5%. One year after that we were at 18% and another year after that we were 33%. So, if you just take a look at the UK it was very, very clear at least here where I live that once you crossed 5% then, suddenly, everything changed and the market took off. so, then I look back to Norway it’s like so what Norway do after it 33% because there’s not that many markets that have gone that far. So, for Norway after it hit 33%, which is where we are in the UK today. It only took them about 4 or 5 years to get to 90%.

Greg Dalton: And you’re talking about percentage of new car sales.

Albert Cheung: Of new car sales, that's right.

Greg Dalton: So, what I hear there is 5 years to get to 1% another five years to get to 5% and then that you know those curves start to bend up. And then a person can also say well the UK is not the world. Are there special policies and how do you extrapolate from two European countries to the rest of the world?

Albert Cheung: Yeah, it’s completely fair to ask that question. So, a lot of other European countries exhibit the same behavior when we looked at the data. It didn't all happen at once, but it has all happened in the last few years. And those tipping points were typically around 5%. But not all at the same time not the same steepness. Similarly, in China, so China is now well pass that tipping point and the same thing has happened there. And so, what are these markets have in common where we’ve seen that happen. All these markets have strong policy support both on the supply side and the demand side. So, they have fleetwide CO2 targets that automakers have to meet, which means they have to bring EVs to market. There are demand side subsidies to subsidize the purchase for the end-user. And that seems to be a formula that is working it works in Europe it works in China. And I think there’s every reason to believe now that it's gonna work in the US as well, which was the point of the article because the US has now reached that tipping point too.

Greg Dalton: Right. So, that has huge implications a course for the auto industry and it gets interesting to note that some companies Ford, Renault are kind of breaking apart the part of the company that makes fossil fueled cars and breaking apart another part of the company that makes electric cars because investors value that more richly. So, does industry dispute these terms or they kind of saying like, oh we see the writing on the wall we better restructure ourselves to be positioned for this.

Albert Cheung: There’s definitely a virtuous cycle going on. One of the things that is an absolutely critical factor for that tipping point to takeoff is that the models have to be available. You need to have a wide choice of vehicles that fit your needs. Whether you want to buy an SUV or a pickup truck or a city car or family van, whatever it is. You need that range of models to choose from and need automakers to be building them in these types of numbers that can really support the market. But they also won’t do that unless the market is there and the policy is in place. So, I think it's all about creating that policy environment where there’s confidence for the automakers to invest. And you’re seeing, you know, recently we saw Ford come forward with its $50 billion EV plan which really just gives me a lot of confidence that we are gonna see that mass-market option in the US in the next few years.

Greg Dalton: Right. So, consumer choice of models has been a big deal. The high-end Porsche etc. all the way down to, you know, economy models, Kia, etc. But in the US the Inflation Reduction Act contains a provision insisted on by Sen. Joe Manchin that only EVs with a specific percentage of American sourced battery metals will be eligible for the $7500 tax credit. Now the automakers are saying a lot of our cars won't qualify yet for this. So, how do you imagine this provision will affect the cost and the consumer choice that you're talking about that’s so important to move forward?

Albert Cheung: I'd first take a step back and say I think where US policy is now as of the time we’re recording with the Inflation Reduction Act pretty much in place is really positive for EVs because we have the new CAFE standards from earlier in the year and they, you know, by our analysis they essentially require EVs to hit about 25% market share by the middle of this decade. So, next three or four years. And so, you have that pull now in the policy side in terms of the supply. And then what the new tax credits in the IRA will do is again subsidize the demand side and don’t forget a lot of the, well, the biggest makers of electric vehicles had already exhausted their tax credit. So, they were gonna come down to zero tax credits. So, even if they can’t get the full 7500 under the new regime it is still upside for them. But you're right the battery materials provision is really interesting. And our view on it is the actual provision of the raw material and there’s plenty of supply from countries that have free-trade agreements with the US.

Greg Dalton: Those qualify.

Albert Cheung: Exactly. The challenge is the refining. Now a lot of the refining happens in other countries like China. So, I think there's going to be this maybe not a reckoning but at least a reevaluation of those supply chains and you could in fact see refining capacity being built in different countries whether in the US or other third countries with free-trade agreement. And that's kind of what the administration I think is hoping to achieve is to see realignment of supply chains to create more value in the US.

Greg Dalton: So, you think that the overall the IRA is positive for electric vehicles. What are the, are there any obstacles to mass adoption that you see out there. around the world?

Albert Cheung: So, we think a lot about housing stock and the physical infrastructure of countries. I think it's clear that countries which have many detached homes, standalone homes with driveways and garages are well-suited to home charging which is after all the cheapest type of charging. In countries with a lot of high-rise living or shared carparks or very dense urban areas where you only park on the street, that's just gonna be more challenging. And so, there’s gonna be a high need for public infrastructure or getting agreement around building charge points in housing developments which just takes more time. And these are barriers that are surmountable, but I think it's clear that you get faster uptake in markets where the charging installation is easy. And especially if there are a lot of two-car households where EV adoption really is a no-brainer if you’re a two-car household with the driveway and actually I think the US is one of those markets where that can be a really good driver. Other markets less so. And then I would also say I mean when I think more broadly about global EV adoption I think there’s a very clear trend of market prioritization from the automakers. Because some markets are just less attractive for OEMs to sell EVs into. So, if you think about the Europe and the US these are large developed markets with high purchasing power. So, when those regions put in place policies that support electric vehicles the automakers have a good reason to invest in electric vehicle production and direct that production into those end markets because those are attractive high-value markets. But for smaller economies and particularly emerging countries with lower purchasing power. It's harder for them because even if they put in place EV incentives it may be that automakers just don’t prioritize production into those countries because they’re not as big they don’t come on this much importance in the portfolio that that automaker is worried about and they’ll prioritize their production to other markets which are high-value. And I think this is an issue that’s gonna get more and more attention because we’re starting to see this gap to emerging markets where in the emerging markets and not approaching those tipping points yet. And I think that’s something that’s gonna get more and more focus.

Greg Dalton: And is it possible that vehicle sales outgrows charging infrastructure that there’s not just not enough as always, is the sort of balance of having enough chargers and putting them where people want them and not too many. So, people see a bunch of empty EV chargers like oh no one is using that, you know, and of course all costs money. Who pays for that?

Albert Cheung: Yeah, this is amazing kind of Goldilocks situation with charging. Because from the charging investor's point of view they want to see really high utilization because that means they’re making money. And from an EV users’ point of view you want to see really low utilization you want to drive into you know Starbucks and see 5 empty chargers that are all working and ready for you, right. So, there's this Goldilocks so kind of where’s the right amount of infrastructure. So, we actually looked recently at these ratios of how many EVs there are per public charge point in different countries. And right now there’s a huge range. Some countries there are five EVs per public charge point and some at 35 EVs per charge point. So, it is different range it turns out there isn’t really a right answer because of what I talked about before in terms of the differences of housing stock and the differences in the mix of how many pure electric versus plug-in hybrids there are in a country. You actually end up just for this different mix of infrastructure. And so, I think in a way the industry is going through this kind of suck and see process of kind of feeling that way towards what works while at the same time try to ramp up very quickly because what we know is EVs are gonna grow very quickly. So, you don't want to get too far ahead of the curve but you definitely don’t want to fall behind it.

Greg Dalton: And it sounds like suburban communities may be those where this can take off most quickly because of you say there’s a driveway charger, etc. rather than urban areas where if you live in apartment building, who pays for the electricity got metering tangles, all that sort of thing. So, density so it's the less urban areas which are gonna see more EV adoptions what sounds like you're saying.

Albert Cheung: And I think especially folks who drive every day like if you have to commute by car. Because you know if you live in an urban environment you’re commuting by public transit. You don't really like the upfront cost of an EV you’re offsetting that cost by very, very low running costs. So, I think if you’re commuting every day, you're in a suburban area driving 10 miles to work, 20 miles to work, that’s the sweet spot really. And another interesting finding from our team recently is that this is Norway so people this is Norwegian examples but anyway, they found recently that EVs are getting more miles driven now than combustion vehicles. And so, this is a combination of factors, but one of them you can imagine is two-car households where they have one EV. They just drive the EV all the time because it's cheaper to run, it's clean. And so, --

Greg Dalton: It’s more fun.

Albert Cheung: Yeah, right, right.

Greg Dalton: It’s just more fun. We’re talking about tipping points in electric cars around 5%. It's happened in several markets seems to be happening in the United States. Auto companies are on board and BloombergNEF did a report recently on peak car. There’s a scenario that was about of what a billion, two cars now going to about 1.5 billion and in 2039. And your group expects worldwide annual sales to peak in 2036 just 14 years from now ending more than a century of growth. Is that good news for the climate? What does that mean?

Albert Cheung: Well, we know for sure that fewer miles traveled makes the climate challenge easier because whatever how many miles passenger kilometers traveled that you've got to deliver into the economy in 2050. That's how much electric vehicle capacity you’re gonna need. So, if you can reduce the amount of passenger kilometers traveled even just by a few percent. That's avoiding a lot of emissions up to 2050. It's avoiding a lot of battery manufacturing you’re gonna need. It’s avoiding a lot of raw materials you need to extract from the ground. So, that's really, really important. Where the peak car conclusion comes from is from our analysis of several trends. One is demographic urbanization trends in the way that we live. And another is actually in model shift and the rise of shared mobility. So, this is about more folks moving over to public transit more folks moving over to active mobility and shared rides and so on and autonomous is part of that because you can imagine that more robo taxi rides meaning less need for car ownership. And so, when you put all of those factors together and what we find is that you want in a world where the number of the cars on the road is forever rising; you do reach a peak. And it may not be that far away, you know, as we say may be less than a couple decades away.

Greg Dalton: Right. Though we have to remember that Uber and Lyft initially started on reducing car ownership; it may have done that but it doesn't reduce vehicle miles traveled because that one car is used by a lot of people and driving around a lot of the day. And studies in San Francisco and elsewhere have shown that ride-hailing services actually increase congestion, slow down travel times. So, what Silicon Valley sold us on at least as an eco-friendly solution didn't play out. How critical is driving down the cost curve to reaching a tipping point and how important are subsidies and other strategies to drive down the cost to reach these tipping points that we’re talking about in autos and other areas?

Albert Cheung: So any of these tipping points and we could talk about other industries as well. But I think any tipping point happens because consumers see a product that comes to market that's become affordable. It's desirable; it's readily available to buy. And most importantly the tipping point is that you can see that lots of other people have like them. That’s what happens; that's what drives the tipping point because we adopt things because our neighbor Joe is adopting it, and he loves it, and this is exactly what we see with EVs. Now, policy is what makes all of that possible. So, consumers exist within this market construct within a social environment that influences the decisions, but it’s policy that creates that market construct. So, the policy is what needs to make sure that the products are brought to market to make sure that they’re brought down in cost and to make sure they’re affordable to buy, you know, I think subsidies is an important part of that. I don't think, by the way, I don't think policies may have made EVs desirable. I think the market did that. I think some very clever and innovative companies did that. So, you know, policy can’t do it all on its own, but I think that the lesson learned here is once you have the right policy environment in place the social and the consumer drivers kick in and then the market starts to deliver.

Greg Dalton: Right. I think you’re saying Tesla without saying Tesla. I mean Tesla really disrupted the global auto market and did things that no incumbent automaker would do. And I think it's helpful to remember that Tesla might not be here if it weren't for a US federal loan guarantees and some federal help in the early days. Tesla was very close to death and had a helping hand from the government to get to where it is. Though sometimes the company doesn't always acknowledge that or likes to reverse that in the past. But this question we were talking about subsidies are important to the markets, you know, electric cars are taking off because they’re just better. They’re more fun to drive, they're cheaper to operate, they're more efficient etc. and all sorts of ways policy didn’t do that policy helped it but word continues to be subsidies. And, you know, let’s talk about those subsidies because when did those get taken away if we’re at a tipping point does the auto industry still need policy support?

Albert Cheung: I do think that's where this all ends up. And I think we’ve seen in China over a period of the last five years that they phased down the subsidies. And that's gonna happen in markets around the world. We've seen it in renewables once renewables became cost competitive it was no longer necessary to subsidize them.

Greg Dalton: And does the industry do that because once the industry is gonna get, you know, they don’t like to give away those, you know, subsidies, right. Do they willingly let go and say because that’s a big criticism made of the oil industry is like, oh, 100 years you’re still getting subsidized? Do they let go of the subsidies when it’s mature and whether it's, you know, yeah?

Albert Cheung: It’s never fun having sugar removed from your diet, right. But I think that you still need to have the very clear policy and regulation that pushes the supply side to keep supplying those vehicles. And the automakers can then set their own pricing strategies, they need to go and compete on building the best product, sourcing the cheapest materials or the best materials. But the regulation is clear you need to meet this fuel economy standard this CO2 emissions standard this percentage of EVs by 2030 by 2035. It's just the subsidies become less and less important as the market grows as the cost of the technology comes down as you phased that out it just becomes a lot less necessary.

Greg Dalton: Is offshore wind in Europe an example? In the 1990s, European governments like Denmark and Britain ordered utilities to buy offshore wind, you know, at high prices and pass that cost on to consumers those consumers kind of created a public good that didn't happen in the US. But, you know, did the offshore wind industry then sort of wean itself off of the subsidies is that potentially a model?

Albert Cheung: Yeah, that’s right the offshore wind industry onshore wind and solar PV are all examples of this where we started out with a subsidy driven model where it was the government had to fill the gap in the business model by providing money to make up the difference in costs. And over time as those industries scaled up, they drove cost out of the equation to the point where they became first of all broadly cost competitive with fossil fuels, but then even undercut them now to the point where today they’re cheaper than fossil fuels in most markets around the world. And so, over time you remove the subsidies because you just don't need them anymore. And I think the same thing will happen ultimately, with electric vehicles.

Greg Dalton: So, we are at a tipping point for EVs and there's policy support in the US and elsewhere. We’ve talked about some of the supply chain constraints. There’s also inflation is a big issue here. This recent US bill in the United States is called the Inflation Reduction Act, and yet I read that lithium carbonate prices a key ingredient in lithium-ion batteries have risen from $5000 per ton about two years ago to $70,000 per ton more than 10X according to a BNEF report by your colleague, head of metals and mining. So, how vulnerable are EVs and other clean energy products to price surges and when they become more popular?

Albert Cheung: This is definitely one of the key issues if we look out over the next 2 to 5 years. The supply and demand of critical materials for EV batteries is absolutely a key issue and we have seen those prices rise over the last couple of years. But one thing to note is that a lot of those materials have come down from the peaks a few months ago. So, the last three or four months we have seen them recede a little bit, which is a good sign. But I don’t want to minimize that because from our point of view supply and demand of critical materials like lithium like nickel like cobalt are very finely balanced over a kind of 3 to 5-year horizon. We do need to see more investment in capacity to bring those materials to market. It's not a reserve problem; there's plenty of it in the ground. We think there’s enough for decades to come. But we need to see investment in the mining capacity and refining capacity to bring it to market and that's what high prices do for you is they deliver that investment signal to the miners to the investors to give them the confidence to go ahead and invest and we think that’s what we’re seeing now but we need to see more of it.

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation about the tipping points for mass adoption of EVs and other clean tech. Our podcasts typically contain extra content beyond what’s heard on the radio. If you missed a previous episode, or want to hear more of Climate One’s empowering conversations, subscribe to our podcast wherever you get your pods. Coming up, what needs to happen for technology to help us decarbonize our economy?

Albert Cheung: I'm a great believer in technological innovation and I do believe that technology can help us achieve net zero globally, but we’ve got to have the right policies

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues. We’ll be right back.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. Billions of people in Asia, Africa, and Latin America can’t afford a car at all – let alone an EV. In India, for example, 430,000 electric vehicles were sold during a recent 12-month period – but only 18,000 of them were cars. The rest? Two- and three-wheelers. Before we get back to our conversation with Albert Cheung about clean tech tipping points, Climate One producer Austin Colón brings us into the world of electric micro-mobility – EVs that aren’t cars – which are transforming the way people travel in urban areas – not just in the global south, but here in the US.

Austin Colón: E-bikes, e-scooters, e-mopeds – they’re all the rage here at the Electrify Expo in Long Island, New York. These vehicles are often categorized under the umbrella term micro-mobility. So what exactly is micro-mobility?

Chase Stubblefield: Micro-mobility to put it concisely is lightweight electric vehicles.

Austin Colón: That’s Chase Stubblefield, Managing Director of Electric Scooter Guide.

Chase Stubblefield: Obviously the things like the bike actually predate the car and even the electric bike is a hundred years old.

Austin Colón: Micro-mobility is a quickly growing facet of urban life: Who wants to drive in traffic, then pay through the nose for parking - if you can even find a spot?, But how could these new vehicles change a real New Yorker’s daily commute?

Jesse Egner: I bike home from Manhattan to Brooklyn, and I take the Williamsburg bridge and sometimes even with like a pedal assist, you know, pedaling up that it's annoying, you know, it'd be nice just to have like a throttle.You could just, you know, just cruise up over the bridge.

Austin Colón: That’s Jesse Egner, an artist who lives in Brooklyn and a citi bike enthusiast. He’s here at the Electrify Expo to check out what else is on the market that could potentially replace the public citibikes for work commute, or just to get around the city.

Jesse Egner: I would need something that is light enough that I could carry up and downstairs when I need to, but also want something that's gonna have good battery power. I know for a fact, I would not commute to work on a bike if it wasn't a eBike,

Austin Colón: But where the train isn’t a good option, Can this technology disrupt our car centric culture?

Chase Stubblefield: 50% of all US car trips are under three miles and that's something to repeat over and over. This is a stat that should be written everywhere, shared everywhere. So if a majority of trips are short, and it gets even shorter when you go to an urban context and then when you go globally, it gets even shorter than that. A lot of people who have micro mobility today, they supplement it with their car and they're just like, well, I save all of this gas and it's actually faster.

Austin Colón: This is Chase Stubblefield again:

Chase Stubblefield: It's so interesting that every inch of really everything related to the car is subsidized. It has everything going for it over a hundred years. And yet still there is so much organic momentum behind micro mobility. Even without the regulation, without the space, without, you know, a medium speed lane or slow speed lanes, It's still thriving and growing 10 X instantly.

Austin Colón: Ten X. That’s far faster than electric cars. So what does the future of travel look like when you include these lightweight electric vehicles?

Chase Stubblefield: I think transit's gonna grow dramatically as micro mobility grows. A lot of commutes into this city will probably start to look like micro mobility, then transit, then micro mobility, or micro mobility, then car then micro mobility

Austin Colón: As someone who lives in a city myself, it is exciting to imagine a future where people can get around quickly on zero emission vehicles.

Austin Colón: For Climate One, I’m Austin Colón

Greg Dalton: I was in New York recently and bike shares and ebikes are everywhere. It’s exciting to see so many commuters and tourists bopping around the city, and weaving through slow-moving car traffic. Let's get back to our conversation with Albert Cheung. Earlier this year, financial giant BlackRock issued a report titled three reasons clean energy is at a tipping point. Those reasons are renewables are cheaper, they are less susceptible to geopolitical turmoil, and demand for them is growing. I asked Cheung if he agrees.

Albert Cheung: I would go further. I would say that renewables have passed the tipping point. I think they are the dominant force in the power system today, not in terms of the installed base. So, I think, you know, in total at the moment wind and solar are only about 10% of global electricity production. But that's a huge step forward from where they were 10 years ago. And there are now I think 10 countries that get more than a quarter of their power from wind and solar, so that’s already impressive. But what I'm really talking about is the annual install. So, if you look at all of the power capacity that's added each year about two thirds are wind or solar. About 80% of it is clean, is renewables. So, if you add in hydrogen or something like that it’s 80%. So, you know, EVs at 5% in the US renewables at 80% globally. So, I think we’re well past the tipping point.

Greg Dalton: So, let’s look at other sectors whether it's heat pumps grid scale batteries. What are other tipping points positive tipping points out there. Technologically,

Albert Cheung: I would love to see a revolution a tipping point around heat pumps. They are the most obvious solution for really a large chunk of the building, heat energy market. And we are seeing growth particularly in Europe where there’s more policy support in place now. We’re seeing acceleration in heat pump deployments. But I don’t think we’re at the stage where we can call it a tipping point yet. the reason for that is the cost is still too high. We need the cost to come down or we need policy to support that. The installers, frankly, the building contractors and the heating engineers are still learning about the technology, they’re still learning how to install and how to upgrade the building envelope to adopt heat pumps. And most of the consumers who are adopting this technology today are still those climate conscious innovators who are willing to go through the kind of nuts and bolts of figuring out how it’s all gonna work and the kinks in the installation process. So, it’s definitely not the mass-market yet, but I hope we’ll get there, you know, if we can get those costs down, get the training done for those installers, I think we can get to a tipping point in heat pumps over the next few years.

Greg Dalton: Right. And we should clarify that heat pumps also cool; they're not very well named. I'm putting some in my house and they heat and cool. Other areas where is it grid scale batteries, you know, vehicle to X or vehicle to home, you know, we’re hearing about that is using your car as a battery for your home when the power goes out, etc. So, if heat pump is number one what other areas will there be some technological tipping points?

Albert Cheung: Yeah, large scale batteries for sure. And I should've said this one before heat pumps because I think it’s further ahead. I think building off the success of electric vehicles we’re seeing such cheap battery technology notwithstanding the inflation we’re seeing this year. But on utility scale storage we’re expecting that market to roughly triple over the course of the next eight years or so. And they’re gonna do that on the basis of being an economic solution being a competitive solution for managing variability and managing flexibility on the grid. So, I think that’s really exciting. It's funny you mention vehicle to X or vehicle to grid. This idea of using the electric vehicle battery as storage because the potential there is just huge. When we look at the numbers up to 2030 the amount of battery capacity deployed inside electric vehicles is gonna be somewhere around 8 to 10 times more than the amount deployed as stationary installations on the grid. So, it wouldn't take a lot, you wouldn't need every car even if you can get one in 10 cars to participate, you might be doubling the amount of grid storage available. So, you know, the potential there is huge.

Greg Dalton: Right. So, mobile power plants and the electric utility executives are really excited about that. There are some issues to and I think the V2H is a lot more, vehicle-to-home is a lot more promising because access my battery for my home where's people been reluctant, owners of electric cars have been reluctant to let the grid cycle their battery and which over time kind of reduces the range or resale value of that car. They’ve been reluctant to do it for the grid, but people might be more reluctant to do it for themselves.

Albert Cheung: I’d like to just talk about one other actually one other industry or sector is hydrogen. We didn’t project hydrogen approaching economic competitiveness really until around 2030. But now we've seen so many commitments from different countries to build out hydrogen infrastructure to build electrolyzer that’s gonna drive the cost down quickly. But in addition to that, because of the very high natural gas prices right now in Europe and in Asia, which just temporarily in this environment where green hydrogen is actually cost competitive with natural gas. Now it's a bit of a theoretical exercise because there’s not a lot of green hydrogen actually being produced today so it’s kind of a spreadsheet comparison rather than real projects out there. But that’s only gonna accelerate that industry so the tipping point for hydrogen may not be today, but it does feel like it's coming.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, I’ll admit that I used to be a hydrogen skeptic for quite some time and I’m just kind of softening on hydrogen as I see green hydrogen and a little more, not for passenger vehicles, but certainly for long haul and for -- and we should mention that green hydrogen is using renewables to split water. So, Albert we’ve been talking about tipping points as if the arc of history always bends toward progress. And once the tipping points are reached by definition, you don't go backwards. Are you a techno-optimist do you think that we can looking at all this do you think that do you feel better about the carbon challenge?

Albert Cheung: I wouldn't call myself a techno-optimist because I think that implies that we can sit back and let the technology do the work. But I'm a great believer in technological innovation and I do believe that technology can help us achieve net zero globally, but we’ve got to have the right policies in place and we’ve got to have the right education so people can understand how to adopt these technologies. You can't just think about technology in a vacuum.

Greg Dalton: Right. And I said that tipping points are by definition can't go backwards. What I think of an example where incandescent lightbulbs were basically the same since the era of Thomas Edison for what nearly 100 years. And there was a move toward better LEDs etc. that provide better light, less heat, more efficient. And yet still there was a big push to claw that back and sort of hold onto that incandescent lightbulb of Thomas Edison's era in the United States. So, can tipping points be undone can empires kind of strike back?

Albert Cheung: Yeah, that's a really interesting question. We've not seen it yet in the main kind of energy transition technologies that we’re tracking. We haven't really seen that at all. And where we have it's been from folks who have a lot to gain from pushing back on the new thing.

Greg Dalton: From the manufactures of the old technology trying to hang on to it.

Albert Cheung: Yeah, the incumbents really who have heavy investments in other technologies and don't want to see the new thing come along. And I think it's up to us as society to be wise to that and make sure that if there is pushback it’s coming from an honest place rather than a place of kind of particular kind of benefits to certain companies or certain sectors for example.

Greg Dalton: Which is where the incumbents, oil and fossils, they have politically entrenched. So, if the markets were as “free” as we think they are sounds like EVs and renewable electricity would win, but that's not the case, right?

Albert Cheung: I think to me I see some really structural differences between the energy transition in Europe, and the energy transition in the US and the reaction to the energy crisis as well is different. And I think one of the real underpinning differences is that Europe's oil and gas industry's best days are already behind it. A lot of the reserves are exhausted, a lot of those companies are already trying to pivot away. Whereas if you look at the US there are still great reserves, very competitive reserves if they were to be exploited. And so, I think it’s a fundamental difference where on both sides where the energy transition is a threat to an industry that still sees opportunity in front of it. And secondly, the energy crisis when we look at very high oil prices, very high gas prices is an opportunity in the US economy for US corporations in a way that it isn't for Europe where it’s mostly a pure threat for Europe. So, I think if you can call it fossil fuel lobbying. You can call it kind of influence in government and influence on the legislative process, but it's also a fundamental fact that those are industries that are the stronger in principle had a brighter future if climate change were not an issue in the US whereas in Europe those days are already behind us and would've been behind us anyway.

Greg Dalton: You're listening to a conversation about the tipping point for mass adoption of EVs and renewables. This is Climate One. Coming up, how can we get investors to choose clean technology over oil and gas?

Albert Cheung: If we can accelerate electric vehicles, accelerate renewables, that will reduce demand for gas and coal and oil and then investors will just invest less in those commodities. That's my theory of change.

Greg Dalton: We’ll be right back

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. With Russia's weaponization of oil and gas during its invasion of Ukraine, moving away from fossil fuels has taken on new urgency in Europe. But is Europe really going to be able to meet its goal of accelerating its transition from fossil fuels? What happens when winter sets in and Russia cuts off supply?

Albert Cheung: From a policy standpoint the position is extremely clear. Europe wants to accelerate the transition to clean energy as a means of removing its dependence on Russian gas. So, that means more renewables, more heat pumps which we talked about more clean hydrogen, also more bioenergy. And so, the repower EU plan, which is the European commission's plan to get off gas calls for more of all those clean energy technologies. It also means importing natural gas from other providers that aren't Russia like the US and the neighboring countries. But I think we can be clear: investments in clean energy are investments in energy security and that’s clearly 100% aligned in the minds of European policymakers. I think with that said, I think there is this back to fossil fuels narrative that goes around. I think there’s a couple of things to be said around that. One is that over the last few years we’ve seen gas power generation, displacing coal in Europe as carbon prices have risen and forced coal out of the market essentially and that’s good for emissions. Now because gas prices are extremely high coal has become more competitive so coal is making a bit of a comeback. And so, I think that's driving a bit of this we kind of reneging on the transition I think that narrative is coming a little bit from here. But I think we should remember this is a short-term issue and power generation is part of the EU carbon market. And that carbon market is being tightened to meet more stringent climate goals for 2030. So, I don't think this is a longtime thing. I think the carbon market is still gonna drive emissions out of the power sector, even if there are some sort of speed bumps along the way.

Greg Dalton: In Russia's invasion, the world saw how nuclear power plants were at risk. Just recently, Ukraine said Russian shelling damage Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, the largest in Europe risking fire and radiation leaks. How much does this factor into the calculus about nuclear as part of the carbon free pathway because nuclear is still seeing policy support. Does that raise questions about nuclear's part of the mix?

Albert Cheung: I think attitudes to nuclear in Europe are shifting a little bit at the moment. If you rewind just a few months at the beginning of the war, Germany was saying we’re gonna do everything we can to limit our gas consumption this year, everything within our power. And folks would say, okay, what about keeping some nuclear, they said, not that. We’ll do everything else but not that. But recently we’ve heard the environment minister in Germany saying maybe we can see a way to keeping one or two of these plants online which really for the last decade, that was never on the table.

Greg Dalton: Ever since Fukushima.

Albert Cheung: Exactly. So, we’re just starting to see a glimmer of that in Germany. But at the same time right now we’re facing a challenge in Europe because the nuclear reactors in France, a lot of them are out of commission right now because of maintenance issues. And so, there’s this kind of fear as well that nuclear is actually not gonna deliver this winter when we need it most. So, it’s really, it’s a complex, you know, there’s kind of points on either side of the ledger right now for nuclear. So, I think time will tell which way that conversation really goes.

Greg Dalton: We recently spoke with Roman Zinchenko, cofounder of a green tech incubator in Ukraine. He said that with the shutdown of heavy industry due to the war, Ukraine is exporting electricity to countries in the west. They’re now connected into the European countries, no longer to the Russian grid. How is, more broadly, how is Russia's invasion restructuring the interdependence of energy flows within Western Europe?

Albert Cheung: We don't fully know yet. I think we’re gonna find out this winter. But there’s been this huge trend over the last couple of decades to have more inter linkages between different European nations and their energy markets both particularly for power but also for gas. And that would allow countries to tap into each other's resources for example, when the winds are not blowing in one country you can bring in the hydro from somewhere else, bring in the nuclear from somewhere else, etc. And we, you know, our analyst team, we've always had this question in the back of our minds, which was what would really happen to that interconnected system that interdependence if the going got really tough. Could a European country really rely on its neighbors in a critical situation to keep the lights on? And I think Putin's Russia is really hoping that the answer is no. That is their gambit is that that they want to they’re trying to pressure Europe using the natural gas weapon and see if that solidarity can crumble to see if we can chip away at the notion of United Europe. So, I think this winter is the test of that; like one side is gonna win. And I think there’s every chance it can be Europe if we can really get across of demand side management across in the UK across Europe. I think it could be the time when we really show that natural gas weapon didn't work.The other issue where does this back to fossil fuels fear is around European countries building out more natural gas import capacity. And also encouraging the US supplies to build up more export for LNG. Now, all of these terminals that are gonna be built need some form of long-term investment case to underpin that investment decision. And that's quite a hard story to tell to the investors. If Europe is going to undergo rapid clean energy transition, then you know what's the role of these gas import terminals in 10 years’ time, say. So, now we have these discussions about how do you future proof those gas investments? How do you make them hydrogen ready for example. But I don’t think we yet really know exactly what hydrogen ready means so that does get quite complicated. But in a way I think the renewables and clean energy piece is the clearest piece and actually what to do about the gas infrastructure is the most complex.

Greg Dalton: Right. Because it seems to be really unclear right now if these high prices are going to accelerate the switch, you know, high gas prices make EVs more economic. But it also makes investment in oil and gas more economic. And we’ve seen record profits from the oil and gas companies in recent quarters. So, is there demand destruction that’s happening or is there expansion of supply, or both. Do we know yet?

Albert Cheung: I think we should always focus on demand. My kind of model of change in my mind for the energy transition is that we need to be removing demand for fossil fuels and actually the supply-side matters less. Because the job of the oil and gas companies, the job of investors in energy is to invest just the right amount and supply so that you can make a return on whatever you think demand is gonna be. So, if we can accelerate electric vehicles, accelerate renewables that will reduce demand for gas and coal and oil and then investors will just invest less in those commodities, that's my theory of change. I think that there can be over worry about high oil prices, driving investment in oil production. People can stress too much about that from a climate perspective. I actually think that’s a slight red herring because really, what happened, what matters is are you gonna burn that oil or not. And if we can get electric vehicles on the road then we’re not gonna burn the oil.

Greg Dalton: Yeah. I can hear your economists talking because so many activists focus much more on the supply-side attack supply, villainize supply, stop supply, you know, keep it in the ground, don't build that new terminal and less on the demand side. So, the Inflation Reduction Act which you’ve been covering, how big a deal is this and how big an impact do you think it will have on the demand side that you say we ought to be focusing on?

Albert Cheung: So, our US team has been pouring over the Inflation Reduction Act and we’ve been talking about it a lot and writing about it a lot the last couple weeks. It's a really big deal. It's the biggest climate and clean energy package the US has ever passed. I think they’re saying $370 billion of climate and clean energy provisions. It tackles all of the major moving parts of the clean energy transition. It tackles renewables, energy storage, electric vehicles, hydrogen, carbon capture, methane, even nuclear, I’m may be forgetting one or two other areas. And it throws decent amounts of money at all of them. So, we think it's a big deal. We think it will accelerate the energy transition. I’ll just take one example, you know, the hydrogen tax credit is worth about three dollars per kilogram I believe at the maximum level if you meet all of the different requirements, if I'm not wrong. And even by our analysis in a lot of markets around the world green hydrogen will only cost somewhere around 1 to 2 dollars per kilogram by 2030. So, 3 dollars makes a huge, huge difference. So, that’s just one example. So, I feel very, very optimistic about the impacts of it. Is it perfect? No. It doesn't put in place any clear targets. There’s no kind of clear standards in terms of how much of these technologies we need to adopt and things like that. But you have to look at it in the context of what the states are doing where you have some of those targets in place that’s gonna pull through demand. And then the money coming from the Inflation Reduction Act really making it easier to meet those terms.

Greg Dalton: So, as someone who's based in Europe following the US, what was your reaction when you saw that the US Congress is poised to pass this bill? How did you feel about it? How did it land with you personally? I know you’re an economist so you don’t have feelings but, yeah, or you’re not supposed to, but you do.

Albert Cheung: I wrote a piece in January about the biggest risks to the energy transition in 2022. And I wrote about inflation, I wrote about rising financing costs, I wrote about recession. But I finished the piece by saying the biggest risk to the global energy transition would be if countries, especially the US come back from COP 26 and fail to pass the policies needed to meet the pledges that they've made in Glasgow. And I said that if that happens, in particular if that happens in the US that will really undermine the process going into COP 27. It would really remove pressure on anyone who's thinking about not raising their commitments and so on and so forth. So, my reaction was this was on the global level, you know, probably the most important thing that could've happened this year to keep the energy transition somewhat on track.

Greg Dalton: Albert Cheung is Head of Analysis at Bloomberg New Energy Finance, BloombergNEF, based in London. Albert, it’s always a pleasure to have you and your insights on the show. Thanks for coming back.

Albert Cheung: Thank you for having me.

Greg Dalton: On this Climate One... We’ve been talking about reaching a tipping point for widespread adoption of EVs and other clean technology.

Climate One’s empowering conversations connect all aspects of the climate emergency. To hear more, subscribe to our podcast on Apple or wherever you get your pods. Talking about climate can be hard-- but it’s critical to address the transitions we need to make in all parts of society. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review if you are listening on Apple. You can do it right now on your device. You can also help by sending a link to this episode to a friend. By sharing you can help people have their own deeper climate conversations.

Brad Marshland is our senior producer; Our managing director is Jenny Park. Our producers and audio editors are Ariana Brocious and Austin Colón. Megan Biscieglia is our production manager. Our team also includes consulting producer Sara-Katherine Coxon. Our theme music was composed by George Young (and arranged by Matt Willcox). Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.