Katharine Hayhoe on Hope and Healing

Guests

Katharine Hayhoe

Summary

The UN Secretary-General António Guterres referred to the most recent IPCC report as a “code red for humanity.” But do we fully acknowledge the severity of the situation?

Renowned climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe says our collective threat meter is “unbalanced,” and that humans’ ability to create psychological distance from risk is one of the biggest barriers to understanding why climate change matters to us.

“We see [climate change risk] as being distant in space; happening over there but not here. Distant in time; happening in the future but not to us. Distant in relevance; happening to people who care about that but not people like me who care about this. And also being abstract, like global average temperature instead of my house being burned down by a wildfire,” Hayhoe says.

In her new book, Saving Us: A Climate Scientist’s Case for Hope and Healing in a Divided World, Hayhoe argues that when it comes to changing hearts and minds, facts are only one part of the equation.

“The biggest problem we have is not the people who willfully decide to reject 200 years of basic science. The bigger problem is the number of people who say, ‘it's real’ but they don’t think it matters to them.”

She’s spent years working to help people understand precisely why climate change matters to them, particularly those who doubt it. Much of that work starts with conversation. Her book relates many stories of the power of conversations that she says begin from the heart, rather than the head. She suggests finding common ground with people before starting to discuss climate.

“If we begin a conversation with something we agree on, rather than something we disagree on, if we begin a conversation by esteeming the other person rather than implicitly judging them like so many conversations begin today, that conversation starts off with so much potential and can end in an incredibly surprising place,” Hayhoe says.

As an evangelical Christian, Hayhoe says she often connects with people through her faith. But she doesn’t put up with those who use religion to deny climate science.

“If people truly took the Bible seriously, they would be out at the front of the line demanding climate action instead of using it as some type of palatable window dressing for their denial which has nothing to do with theology and everything to do with political ideology,” Hayhoe says.

At the end of the day, Hayhoe says finding hope around climate disruption begins from a dark place: acknowledging just how bad it is, and the fact that a negative outcome is more likely than a positive one.

“But hope is that faint, small, bright light at the end of the dark tunnel that we head for with all our might and all our strength. And when we get dragged down, when we get discouraged, when we get anxious and depressed...we take a breath, we fix our eyes on that hope...and then we pick ourselves up, and we keep on going because what is at stake is too valuable to lose,” Hayhoe says. “It's not our planet itself: it will orbit the sun long after we’re gone. What’s at stake is literally us.”

Related Links:

Saving Us: A Climate Scientist’s Case for Hope and Healing in a Divided World

These Trees Are Not What They Seem, Bloomberg article

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. In her new book, renowned climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe argues that when it comes to changing hearts and minds, facts are only one part of the equation.

Katharine Hayhoe: The biggest problem we have is not the people who willfully decide to reject 200 years of basic science. The bigger problem is the number of people who say it's real but they don’t think it matters to them. Because you can say, sure it's real, but if it doesn't matter to me why would I want to fix it?

Greg Dalton: Dr. Hayhoe has spent years working to help people understand climate science and why it matters to them. But with the IPCC’s latest dire projections, where does she still manage to find promise?

Katharine Hayhoe: Every action matters, every bit of warming matters. Every choice matters. So, now more than ever, everything that we do matters. And that is scary, but it also offers some hope because we have the opportunity to truly alter the future of our planet.

Greg Dalton: Katherine Hayhoe on hope and healing, up next on Climate One.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. Our show believes talking about climate more is one of the most important things people can do to decarbonize our economy. No one makes that case better than climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe, my guest on today’s show.

Greg Dalton: Before we get into that conversation, we’re continuing our look at the countdown to the COP26 summit.

Greg Dalton: From the Kyoto Protocol in 1997 to the recent Green Deal, the European Union has consistently been at the forefront of the global climate effort, pursuing progressive policies and emissions targets. Climate One correspondent Aman Azhar looked into whether the EU is poised to drive the global climate agenda in Glasgow.

Aman Azhar: While the US works to convince its partners that it’s really back at the climate table, the European Union remains a consistent climate leader on the global stage.

Bridget Woodman:The EU has got a real history of trying to demonstrate leadership in addressing climate change. And so, it's got very ambitious goals if you compare them with other countries.

Aman Azhar: That’s Dr. Bridget Woodman, Deputy Director of the Energy Policy Group at the UK’s Exeter University. The EU’s Green Deal has gained attention in the international climate negotiations for taking aggressive steps to improve its targets.

Bridget Woodman: So, what we’ve seen recently is a publication of updated targets for 2030, where the EU wants to reduce its emissions by 55% which is putting it pretty much ahead of the field globally.

Aman Azhar: The Climate Group’s director Tim Ash Vie says the EU’s strength lies in its power as a collective that broadens its sphere of influence.

Tim Ash Vie: It represents the voices and actions of many countries, and changes that are made in the European Union are felt across Europe, of course not all European countries are members of the EU, but also across the world. I think, in more recent times, the Green New Deal has changed the conversation about climate action in Europe.

Aman Azhar: But most industrialized countries, including the US, have in recent years put in place policies and measures to drive decarbonization or reduce greenhouse gas emissions. So, what's unique about the EU climate ambitions?

Bridget Woodman:The EU is introducing much more stringent regulations on how much carbon dioxide vehicles, cars and vans can emit and I think you can look at that as something that could be adopted in other countries. I think another area where the EU stands out is the scale to which is put in place support for the deployment of renewable electricity generating technologies.

Aman Azhar: The US and EU have set similar emissions reductions targets. The difference lies in policy implementation, says Daniel Wennick, head of Swedenergy in Brussels.

Daniel Wennick: The US has many more means to implement policy because it's one country. You have the EPA, Environmental Protection Agency and you have federal taxes. EU does not have joint taxes in the same way and it requires unanimous decision making for taxes. So, therefore, EU has gone for a sort of market-based reduction system of EU ETS and then more have national targets.

Aman Azhar: Experts agree that the EU’s climate ambitions are anchored in concrete legislation and policies put in place through measures such as the Green Deal to achieve net zero as quickly as possible. But some of its policies, such as a carbon border adjustment mechanism - which would put a carbon price on select imports - are also contentious, says Bridget Woodman.

Bridget Woodman: It's an important step, both in terms of consumers recognizing that there is a price to pay for carbon emissions. And it's an important step also for politicians to realize in countries seeking to import things into the European Union, that actually they have to think about how their goods and services are produced. So, I think it sends out a very strong message the degree to which other countries might want to adopt that in the short term, I think is questionable just because it's quite a big step.

Aman Azhar: Some argue that proposals such as the carbon border adjustment mechanism can incentivize a bigger push for a universal emissions trading system at COP26. This year’s COP will also be a test for EU’s leadership credentials and whether other countries emulate its climate ambitions. For climate one in Washington DC, this is Aman Azhar

Greg Dalton: Katharine Hayhoe is a climate scientist and Professor in Public Policy and Law at Texas Tech University. She has been named one of Time’s 100 Most Influential People, and was a lead author for several National Climate Assessments. Dr. Hayhoe’s latest book is Saving Us: A Climate Scientist’s Case for Hope and Healing in a Divided World. The UN Secretary-General António Guterres referred to the most recent IPCC report as a “code red for humanity.” But in her book, Hayhoe writes that because the scientific community has to operate by consensus, its observations and scenarios are inherently conservative. I asked Katharine Hayhoe how worried she is that the reality is even worse?

Katharine Hayhoe: Well, anyone who thinks I’m an optimist needs to read that very carefully because as a scientist we have to be realists. And we know that that is the case. We are systematically biased to the direction of underestimating the rate and pace and magnitude of the change, the extent to which it’s affecting us and the potential for really nasty surprises in the climate system. But that’s why I think the IPCC's conclusion is so powerful. They first said this when they released 1.5 degree report in 2018 and it still stands just as true today. They said, every action matters, every bit of warming matters. Every choice matters. So, now more than ever, everything that we do matters. And that is scary, but it also offers some hope because as my co-author Katharine Wilkinson said, I was one of the contributors to that amazing compendium All We Can Save of 60 women’s voices on climate. She said, what an amazing, I’m paraphrasing her exact words but what an incredible time to be alive when we have the opportunity to truly alter the future of our planet. That is the responsibility that lies in our hands today.

Greg Dalton: Right. Though the UN also warned that even if all the current emissions pledges are fulfilled in Glasgow and for Paris the world will still warm by 2.7°C so it’s not just that the pledges aren’t being fulfilled but they’re not enough to get the job done.

Katharine Hayhoe: That’s right. And the pledges have improved. So, a year ago we were at about 3° so at least we’re now below 3 but we’re still not at 2 let alone one and a half. And that is changing. So, I'm from Canada and we just had a federal election in Canada where the party in power, the liberals, upped their climate commitment. They are now aiming for 40 to 45% reduction in carbon emissions for the whole country of Canada by 2030, which would actually skate in right at the edge of Canada’s contributions to the one-and-a-half-degree target. So, we are seeing other countries stepping it up but that’s why Glasgow is so important. Because Glasgow is like a potluck dinner every country brings a different dish. One might be a salad, one might be planting trees. One might be clean energy, one might be a dessert, you know, they’re all different. But when you all come together and you bring your dish and you put it on the table it is painfully obvious and awkward who hasn’t brought enough to go around. And that’s why these meetings are so important.

Greg Dalton: I’ve often referred to the Paris construct as a fitness plan like you're going to do yoga. I'm gonna do Pilates. Everyone is gonna lose weight or lose our carbon weight. But I think the potluck analogy is better because of that visibility you talk about everyone literally puts it on the table that’s yet another great example of your communication. You note that the parallels in terms of politicization of the response to COVID and climate they’re both collective response challenges; they're both invisible threats. COVID can kill you directly, climate can kill someone indirectly. We've been down this road before. How do we get off this politicization?

Katharine Hayhoe: Well, that’s exactly how I had to start the book up because here I am writing a book about climate change during COVID and I was watching communication on COVID on basic things like masks and vaccines which you might say this is not rocket science, people. We all have vaccines that we already have when we’re children. Wearing masks is a very normal thing and I watch it fall right into the same polarization pit as climate change. In fact, one of my favorite cartoons and I say favorite because you kind of have to have some dark humor sometimes is a cartoon of two medical professionals standing by a door labeled COVID saying well surely if we just tell the facts to the American people, they’ll do the right thing. And then you see two scientists by a door labeled climate change were literally rolling on the ground laughing.

Greg Dalton: Right. And so, we’ll talk about the limitation of facts later. But this does get to sort of, you know, risk assessment. And you say that our collective threat meter is unbalanced. On the one hand, people see climate as distant, right, but distant threats from government action to curtail the climate as imminent. So, the bad things are happening far away, but the cost and this perhaps sacrifice or inconvenience happen here and now. So, let's talk about how people react to that spatial difference you know, oh, I have to pay something today for a future benefit.

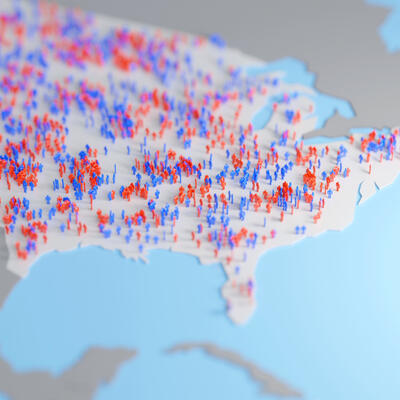

Katharine Hayhoe: Well, psychological distance is one of the biggest barriers we asked to understanding why climate change matters to us. We as humans have this built in sense of just sort of pushing risks off. If we see them as being distant in space happening over there but not here. Distant in time, happening in the future but not to us. Distant in relevance, happening to people who care about that but not people like me who care about this. And also, being abstract like global average temperature instead of my house being burned down by a wildfire. Climate change ticks every single one of those boxes. In fact, if you look at the Yale program on climate communications public opinion maps which are just absolutely fascinating. They have maps for each county and each congressional district in the United States and they even have some maps for Canada and they ask people a series of questions. So, as of last year well over 70% of people said climate is changing, it will affect plants and animals, so nonhuman species, right, not relevant to me. It will affect future generations, distant in time. It will affect people in developing countries in space and then they ask, will if affect you and all of the sudden the number plummets by more than 30%. That is psychological distance and that is the biggest problem we have. So, I know that the dismissives get the most airtime. I know that the people who say climate change is a hoax they get the most airtime. But they’re only 7% of the population. The biggest problem we have is not the people who willfully decide to reject 200 years of basic science. The bigger problem is the number of people who say it's real but they don’t think it matters to them. Because you can say, sure it's real, but if it doesn't matter to me why would I want to fix it?

Greg Dalton: Yeah, that’s the disengaged part. And that part has been growing the part of the Yale Six Americas spectrum. We tend to think of it as a binary you believe or you don’t and you write it’s not a belief it's a fact. So, that disengaged part there are concerned and alarmed but that disengaged part I think that's right. That there’s a lot of people who say oh it's the deniers problem if they would just flip this thing would open up and be solved. But there's lots of people who acknowledge it who don’t deny it, but they're not really taking it into their lives or into their daily action. I think also one reason people avoid talking about climate is because they don't want to engage in conflict. You have all the strategies for connecting with people who disagree and still you receive hateful messages from people who don't even know. How do you deal with that?

Katharine Hayhoe: Well, I get these messages every day and today was a bit on the high side so I’ve had at least 25 today. Most days I get one or two. And they come from dismissives. They come from people who, my personal definition which I probably mentioned to you before Greg, people who if an angel from God with brand new tablets of stone saying global warming is real appeared before them, it would not change their minds. So, why would I think I could? So, I don't start a conversation to argue. And if somebody argues with me, I respond once and if they continue to argue rather than using the resources I provided, I’m done. I step out. Because if we begin a conversation by disagreeing over something, it is very rare it’s not impossible, but it is rare for it to end in a positive direction. But here’s how we can flip it on its head. If we begin a conversation from the heart rather than the head. If we begin a conversation with something we agree on, rather than something we disagree on. If we begin a conversation by esteeming the other person rather than implicitly judging them like as so many conversations begin today, that conversation starts off with so much potential and can end in an incredibly surprising place. And in my book, I tell so many stories about these different conversations that have happened in different ways and ended up really in unexpected and incredibly hopeful perspectives and points of agreement. Because when it all comes down to it we’re all humans, we all live here.

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation with climate scientist and author Katharine Hayhoe. Our podcasts typically contain extra content beyond what’s heard on the radio. If you missed a previous episode, or want to hear more of Climate One’s empowering conversations, subscribe to our podcast on your favorite app. Coming up, how to connect on climate change in a more effective way:

Katharine Hayhoe: Everybody has morals. Everybody has values, everybody has reasons why they make decisions and if we take the time to get to know them, most times they are values we’re gonna esteem, they’re priorities that we can respect. And if we connect climate change to what they already care about, immediately we’re talking on their terms not ours.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton, and we’re talking with Katharine Hayhoe about communicating climate science, particularly to those who doubt it. In her new book, Saving Us, she writes about visiting a Rotary Club in Texas and what she learned from that experience.

Katharine Hayhoe: So, I was invited to speak into our local Rotary Club for the first time. And I had carefully prepared a presentation that connected with who people were and where they live. So, I talked to about Texas because we all lived in Texas. But I walked in and I see those giant banners, you know, up in the lobby that says, the four-way test. Is the truth, is it fair, is it beneficial to all concerned. And I look and I thought that’s climate change. Is it the truth? Yes. Is it fair? Absolutely not, that's why I’m a climate scientist. It’s the most profoundly unfair thing and exacerbates all the other injustices too. Will it benefit people to fix it? Yes. So, I skipped the buffet lunch. I went and perched on a seat in the corner of the hotel ballroom. I got my laptop and I rearranged my presentation into the four-way test. So, I got up there and I could see a few people giving some side eye to the woman who’d invited me. Like we know what you did there and you’re not gonna get on this committee again was what those looks were seeming to say to her. And there was a lot of sort of folded arms and leaning back, you know, I’m just gonna give her the, you know, I’m gonna give her this time because that’s what we do but I’m not gonna agree. But then I started, in with the four-way test. And so, immediately those were their values and I was esteeming their values so much that I was basing everything I was saying around the test and applying their test to what I had to say. So, instead of applying what I had to say to them I was taking their standards and applying them to me. And I went to the four-way test and I could see, I could see the arms unfolding I could see, you know, people leaning forward I could see people even starting to nod. And at the end, I will never forget a local banker who I had met before couple of times came up to me with the most bemused look on his face. And he said, I never thought too much of that whole global warming thing which is the very polite text in way of saying I thought it was a load of crap. But it passed the four-way test in other words, what can I do? That’s my value system. It tested it, it passed I got to agree. That is the incredible power of starting out with our own values and our own priorities and our own sense of what is right. But recognizing everybody has morals. Everybody has values, everybody has reasons why they make decisions and if we take the time to get to know them, most times they are values we’re gonna esteem; they’re priorities that we can respect. And if we connect climate change to what they already care about immediately we’re talking on their terms not ours.

Greg Dalton: Right. The person, one of the people we both know Ed Maibach, who’s a researcher in climate communications talks about a neighbor who mentioned every time that he would talk to her that she was a Goldwater Republican, and never mentioned climate. But one day she came to him and they opened up a conversation. So, it’s getting to know each other trust messengers all the things that I think so many people start with preaching and converting and talking rather than listening at the beginning of conversations. Tell us about your uncle who dismisses climate disruption and the mistake you made trying to persuade him.

Katharine Hayhoe: Well, so my uncle had been having conversations with my dad for quite some time. My dad is a former science teacher himself. And so, finally he sort of got up a head of steam and decided he was gonna email me all his objections. So, he emailed me a very long list of objections to do with the basic science because he’s a very smart man and he’s very educated. And so, his arguments were couched in very technical language related to the absorptive properties of greenhouse gases and their infrared, vibrational and rotational bands and so on. Fortunately, since I’m an atmospheric scientist I can understand what he was saying. And so, I made the mistake of replying factually to all of his objections. So I said, well, that’s a good question because, you know, it is a good question even if it was answered 200 years ago still a good question because somebody asked it 200 years ago, right? So, that’s a good question and here’s the paper that responds to this and here’ s this and here’s this answer here and you know I have these little Global Weirding videos on YouTube and they sort of explain this in the simpler way if you want sort of a big overview. So, I sent him this detailed email that addressed every single one of his points. And I said, after you reviewed this let me know if you have any questions. How many minutes do you think it was until he replied, Greg?

Greg Dalton: I don’t know.

Katharine Hayhoe: Not many.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, right on it, yeah.

Katharine Hayhoe: So, he didn’t actually use any of the information I sent him. He just replied immediately with more whack a moles; it’s like the whack a mole game at the fair. As soon as one mole pops out you whack it on the head with a hammer, we’re not talking about real moles here, these are not really animals they’re just mechanical. You whack it with a hammer, another one pops up and they will keep you doing that ad nauseam.

Greg Dalton: Right. That’s their game. You take the bait so it’s that where it’s at that factual level of discourse where you’re saying you talk about values and not go fact for fact. But then in an age of disinformation, do we let just as you know, false, alternative facts or disinformation go unanswered? That's a conundrum.

Katharine Hayhoe: I don’t. And in fact, if you go to my twitter feed today you will see me not doing that because there's other people listening. I have no illusions that I’m gonna convince people who invested their entire lives in climate denial to turn around because of anything I ever say or do. No illusion whatsoever. But when there’s other people watching I’m gonna respond. I will respond, once now say I’m sorry sir that is incorrect and I do mean sir because 99.9% of the time unfortunately it is somebody who looks pretty male from their name and their picture. I’m sorry, sir, but that's not accurate. Here's the information please update your understanding. And I do that not for that person but for everybody else. And for the .1% chance that maybe that person will look at it once in a blue moon someone does. But then, 9 times out of 10 they fire back immediately. And then sometimes if I have the time, I’m like, no, please go back look at that resource and here’s another resource but don’t respond to you have to take a time and they never do. Sometimes they just ignore it, sometimes they pretend they did but it’s clear they didn’t from what they’re saying. Sometimes they ridicule the resources like my favorite was somebody says something that wasn’t true and I sent them the fourth US National Climate Assessment, which was authored by 600 scientists. It was peer-reviewed by the National Academy of Science by every federal agency. It was based on 100 peer-reviewed papers. It was like one of the most peer-reviewed documents you could send anybody short of the IPCC. So, I sent him that and he said, oh I don't read propaganda send me scientific information. I’m just like, no hope, no hope at all.

Greg Dalton: I recently talked to a person who referred me to a book called Unsettled and I know what that's about, that the science is unsettled. And I’m like okay and this is a person who supposedly science-based nonprofit and conservation organization. So, we know we’re wonderful walking contradiction some of us. The climate scientist Faith Kearns recently wrote a book titled Getting to the Heart of Science Communication. She says scientists need to be more emotional themselves when speaking about climate science, they should consider the trauma that they may inflict on people. So, when you're talking about painful scientific realities, how do you know how to deliver the message and, you know, it seems like an odd thing to the scientists to be more vulnerable and emotionally open when they're being attacked all the time, is that possible or advisable?

Katharine Hayhoe: Well, you're absolutely right we are. And we have our own emotions too obviously about what's happening. But I think that there’s two examples I think of times when I personally when I’ve seen somebody else who I really respect open up emotionally. And the impact that had has just been incredible. So, I am part of an organization called Science Moms. I helped to cofound it along with about 12 of my fellow scientists. And we’re all mothers and that’s a big part of why we care about climate change. And so, if you check out sciencemoms.com and there’s these videos that some of my colleagues made about themselves and their children and climate change and how they feel about it. I have to have a Kleenex in my hand every time I watch these videos. These are not actors, these are climate scientists. They’re not scripted, they're just speaking what's in their heart. And the power of that and the impact of the Science Moms campaign has had because of us being willing to be vulnerable and being willing to talk about how much we love our children and how we would do anything for them and how we’re scared and how we wake up in the middle of the night and we clutch them a little closer to us. And, you know, how close wildfire has come to our home or how we despair about the world that we’re leaving to them. I think that's incredibly powerful. And Renee Lertzman who’s a psychologist who you’ve spoken to before. She often says the first thing we need to do is we need to acknowledge this. And we often sort of shove it down just to keep functioning from day to day but acknowledging it is really important. And so, one of the scientists who I respect most too is a good friend to Climate One is Ben Santer. And he is such I mean, you know, National Academy of Sciences lead author on IPCC for years has endured arguably more personal attacks in his life, more hate, more aggression, more threats than almost any other climate scientist I know. And yet he remains one of the most empathetic people. One of the people who just cuts to the heart of the issue who understands the emotions that drive these people to reject the science but also understands the emotions that drive us. One thing that he said to me of many that just absolutely stick with me is speaking of dismissives, he said they cannot create. They can only destroy. We, we create and that is why we do what we do. And so, just being so profoundly aware of what it is that we are doing and why we’re doing it we create, we study, we protect, we serve. That is why we do what we do and when we communicate that to people along with our science other people want to protect other people want to serve other people want to create too. And that is how together we can create that better world.

Greg Dalton: Creating with an open heart. Katharine Hayhoe is a climate scientist professor at Texas Tech University. Chief scientist for the Nature Conservancy and author of the new book Saving Us: A Climate Scientist’s Case for Hope and Healing in a Divided World. Katharine, you talked about moms and how that group that you mentioned with science and mothers, 2020 was the deadliest year on record for environmental activists with 227 people killed for trying to protect their homes or communities and the people and places they loved. One such activist was South Africa's Fikile Ntshangase who had been questioning a local coal mine that was literally undermining her town. Here is Fikile’s daughter, Malungelo Xhakaza speaking to Global Witness.

[PLAYBACK]

My mom was murdered on the 22nd of October in 2020. If I was home I'd have tried to do something and then my son would have lost both my mother and I on that very same day… After my mom's murder, community members are mostly scared. we are afraid to even ask questions at a meeting about electricity, at a meeting about water a meeting about schools because you don't know what might cause you to be a target i don't believe that my mom's murder should cause us to be silent i don't think her legacy will live on if we live like that. I think she wouldn't have wanted us to just give up.

Greg Dalton: Katharine Hayhoe, you said you've gotten used to being hated yourself. What's your reaction as a mom with a daughter to stories like that?

Katharine Hayhoe: I mean, I’m wiping my tears right now because as a mother I mean you know that her mother would have done anything to protect her and she did; that’s exactly what she did. And that’s why we all fight is for that better future. It reminds me of a P.D. James novel that I quote in my book called Children of Men. And it talks about how a global flu pandemic sweeps around the world and as a result, people can no longer have children. Gradually the number of babies being born dies off and dies off until there’s no more children. And children are what embody our hope. Children are literally the physical embodiment of our hope for the future. They are what carry ourselves into the future. And so, in that book one of the characters said, one would be willing to suffer and even to die for the hope of a better and more just and better future, but not for a future where all too soon the very words justice and suffering would just be blowing in the wind. So, the fact that we have children and not just personally our own children. We might have nieces and nephews or grandchildren or godchildren. We might just have children we know who we just see the amazing children who are doing the children's climate strike and suing the federal governments in multiple countries. They are our future and they are what give us hope. And that's why we fight for that better future. And it's an uphill fight because we're fighting against the balance of power and wealth in this world. The majority of power and wealth in this world as you know, Naomi Oreskes and her work on Merchants of Doubt has documented it in detail. It was acquired through extracting, processing, selling or making things that burn fossil fuels. And so, maintaining the status quo is of great interest to many people to maintain their bottom-line. And what we're talking about is we are talking about a fundamental change in our entire society and economy that is in many ways even from a justice perspective too equivalent to the shift from slavery until the freedom that people have today. That is the size of the transition we’re talking about and make no mistake there are many arrayed against us, many. They’re doing everything they can to silence us to intimidate us to shut us up to tear mothers away from their children. To hide the fact, and this just absolutely blows me away, Greg, that we don't know this. To hide the fact that air pollution from fossil fuels is responsible for almost 9 million premature deaths every single year just air pollution. We are at about 4 1/2 million deaths from COVID. And every premature death is a tragedy. Every single one. But everybody knows about COVID deaths. It is in the top of the headlines every single day. Yet 9 million every year from fossil fuels why is that not a global outrage?

Greg Dalton: Right. I think it’s because it’s indirect because we burn fossil fuels and then something happens in outer space and it comes back and, you know, there isn’t that direct causation the systemic causation versus direct causation. And for the reasons you cited earlier it’s not a tiger in the woods or a man with a gun, that link is hard to see and it’s our brain, you know. George Marshall and others have written books about how climate is perfectly wired to stump our brains, right, we did not evolve to respond to threats like this of our own making. We evolved with all sorts of great cognitive abilities to perceive threats but climate it thwarts all of our evolutionary brains in a way that we’re struggling with.

Katharine Hayhoe: Well, it absolutely does but talking about the health impacts which again is something that Ed Maibach is an expert in. It cuts right across some of those and brings it a little bit closer to home. Like so, burning fossil fuels produces most of the carbon emissions that are wrapping an extra blanket around the planet, causing it to warm. Agriculture and deforestation are the remaining 25%. And these are invisible, we can't see them, we can't smell them and the impacts are indirect like you say. But burning fossil fuels also produces the particulate air pollution that we breathe in that we can actually see with our eyes, the kind of hazy skies we can actually feel it burning our lungs in some places like, you know, if you're in Delhi or if you are in some cities in China you can feel it burning your lungs. You actually start coughing like the wildfire smoke, you know, you can see it outside, people don't wanna let their kids outside and there’s even a number of premature deaths in California that have been attributed and can be attributed to wildfire smoke. So, that sort of I think cuts a little bit across some of that remote aspect of climate and brings it immediately here to home where we can see it, we can feel it and we can experience it right here today.

Greg Dalton: You're listening to a conversation with climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe. This is Climate One. Coming up, we talk about the role of religion in climate denial and delay:

Katharine Hayhoe: So, honestly if people truly took the Bible seriously, they would be out at the front of the line demanding climate action instead of using it as some type of palatable window dressing for their denial which has nothing to do with theology and everything to do with political ideology.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. We’re talking with renowned climate scientist and evangelical Christian Katharine Hayhoe. Recently, eight late-night comedy shows united to address climate on the same evening. Hayhoe was featured on Jimmy Kimmel Live, which began with this:

[PLAYBACK:]

Jim Bakker: It’s not global warming. It’s God’s judgement coming to this country.

Janet Parshall: Environmentalism has become a radical movement, something we call the green dragon.

Shane Vaughn: Scientists from the pits of hell – how dare you take from Yahweh the sovereign right over the weather!

Calvin Beisner: When I was six or something like that, I opened up a birthday present that I didn’t like, and the person that gave me the gift was there, and it just crushed that person. And I think that’s kinda how we’re treating God when he’s given us these gifts of abundant and inexpensive fuel sources. God’s buried those treasures for us because he loves to see us find them.

Rick Santorum: We were put here on this earth as creatures of God to have dominion over the earth for our benefit, not for the earth’s benefit.

[END PLAYBACK]

Greg Dalton: That was Rev. Jim Bakker, Janet Parshall, Pastor Shane Vaughn, Calvin Beisner and Sen. Rick Santorum. Katharine Hayhoe, as a devout Christian, what did you think when you heard those quotes invoking God dismissing climate reality?

Katharine Hayhoe: I thought they haven’t read the Bible because that's not what the Bible says.

Greg Dalton: And what does the Bible say that you think they misquoted there?

Katharine Hayhoe: Well, first of all, in Genesis 1, chapter 1 which is the very beginning of the Bible and the Torah. It says that God gave humans responsibility and the old-fashioned word is dominion over every living thing on this planet. And the word that same Hebrew word it’s actually a Hebrew word that says radah and you look for where else it’s used and in other places it’s used to denote a ruler who cares for the needy and the helpless who watches out for those who are marginalized. Who takes care of them and lifts them up. So, it’s very clearly not about raping and pillaging, it's very clearly about being responsible for being a good steward for it, care taking. So, it’s not, we weren’t given dominion for us it says we were given dominion for the other living things which of course include humans as well. And then at the very end of the Bible it literally says God will destroy those who destroy the earth. And in between all the way through it’s all about that caring for the most in seemingly insignificant aspects of creation, the lilies of the field the birds and the butterflies, the least of these the young children, the poorest and most vulnerable, the orphans and the widows who in those days had no protector. So, honestly if people truly took the Bible seriously, they would be out at the front of the line demanding climate action instead of using it as some type of palatable window dressing for their denial which has nothing to do with theology and everything to do with political ideology. They don't want to fix it. But if I say I don't want to fix it and but it's real and it's affecting the poorest and most marginalized people, as well as all God's creation that would make them a bad person. So, instead they come up with religious-y, piousy-sounding arguments which are so full of holes that as soon as you open the Bible, they fall right apart. But unfortunately, they do so to deceive so many who don't crack a Bible either.

Greg Dalton: And that dominion often sounds like domination, right, which is a very male, patriarchal, kind of thing you said you are part of that group of women who said all we can save. How much is religion and fossil fuels, and patriarchy all tied together?

Katharine Hayhoe: Oh, it absolutely is and it goes back a long way. You go back to the discovery of oil in Pennsylvania there were ministers writing about how it was God's gift to humans to subdue the earth, this is not new. Humans were humans whenever they were alive. And actually, the connection between American religion and politics goes all the way back to the American Revolution when people first parted ways with the religious hierarchy of the churches that were originally based over in the UK for the Anglican or Episcopalian church and over in Rome for the Catholic Church. So, as they began to part ways that’s where individualism rose up. That’s where my opinion is better than your fact or centuries of study came from. And that is where it has actually ended us up today in a place where as Isaac Asimov said he said, you know, a dangerous threat of anti-intellectualism runs through American life to where people literally think my opinion is better than your facts. And today, updating it, my Google search is better than your peer-reviewed paper.

Greg Dalton: You say that you are a climate scientist because you are a Christian. What do you mean by that?

Katharine Hayhoe: Well, I was planning to study astrophysics and my undergraduate degree is actually in astronomy and physics and my first five papers are in that field. I had almost finished my undergraduate degree and I was planning to head to graduate school to continue my studies when I needed an extra class to finish my breadth requirements. And I looked around and there was a brand-new class in the geography department that was taught by someone who had just come back from doing a postdoc with Steve Schneider. I had never heard Steve's name before, didn’t know anything about him but he had so inspired Danny Harvey who is teaching the class this man was on fire. And so, I unsuspectedly wandered into this class, little knowing what was gonna happen and was confronted with the urgency of climate change and confronted with what we now today called the intersectionality of climate change. But that’s a very long word for a very simple concept which is just that climate change is not only an environmental issue, which it is. It is also a food issue, it is a water issue, it's a health issue, it's an economic issue, it's a national security issue. It is an issue of poverty and hunger and lack of access to clean water, and political instability and refugee crises. Climate change is an everything issue and it affects everybody on this planet. It affects the poorest and the most marginalized people more than anyone. And if we don't fix it, we won’t be able to fix anything else that’s wrong with this world. So, as a Christian who believes not only that we are to care for this incredible planet that we live on but even more that we are to care for the poorest and most vulnerable people that climate change is not fair. They didn’t do hardly anything to contribute to the problem. The 3.5 billion poorest people in the world have contributed to 10% of greenhouse gas emissions. And so, I thought to myself how can I not do everything that I can to help with this global problem. And surely, it’s so urgent that we’ll fix it soon and then I can go back to studying galaxies.

Greg Dalton: You note that white evangelicals in the US are less worried about climate than any other group. How do you make sense of the people who ostensibly share your beliefs but prioritize tribalism over caring for the poor, the hungry, the sick as the Bible calls us to do?

Katharine Hayhoe: Well, I had no idea that even existed before I moved to the states, I was so surprised when I was first confronted with it, that I almost couldn’t believe it. I thought to myself what Bible are they reading, is there some different translation I’ve never heard of before? But I wanna just add one thing to what you said though there, Greg. And that is that it isn’t only white evangelical Protestants at the bottom it is also White Catholics. They are right there together at the bottom sort of neck and neck for the lowest place and depending on when you do the survey they should trade back and forth. But the most concerned people group in the whole US when you divide people by religious or nonreligious affiliation is Hispanic Catholics. So, that's where you start to think okay, same church, same pope, same encyclical Laudato si’, how could Hispanic Catholics be the most concerned and White Catholics be the least concerned, it can’t be the Pope, it can’t be the church. It’s got to be something else.

Greg Dalton: And we should say Laudato si’ was an encyclical where Pope Francis really came out strong for climate action as a moral issue. And so, you are saying that why Hispanics do they Laudato si’ do they pay more attention to Pope Francis than others or is it something else?

Katharine Hayhoe: Well, yes, I think they do pay more attention to Pope Francis clearly. But John Evans who is a sociologist at UCSD when he saw this poll results starting to come out back in like the early 2010s, he said as a sociologist, well I’m gonna try to untangle why that is. It’s really where people go to church, that is, is that the tail that’s wagging the dog so to speak, is that the driver of this. And it turns out that that is simply a symptom or a characteristic. The driver is and you can probably guess it's no surprise, the driver is politics. But it's gotten to the point in the United States, where some people, many people have written their statement of faith, so to speak, metaphorically speaking, based on their political ideology rather than the Bible. And if the two come into conflict they will go with their politics over the Bible. As an example, during the election when Trump was elected as president. They polled people coming out afterwards and they said would you consider yourself to be evangelical? And of course, many people said that they were. And then they asked them one more very telling question that people who ask polls say this is a question that sort of defines the sheep from the goat, so to speak in terms of who is actually serious about their faith. They said, how often do you go to church? And about half the people who self-identified as evangelicals who had voted for Trump said that they don’t go to church at all. So, that’s why in my opinion they’re not evangelicals, they're political evangelicals or just political Christians or they’re just political deists to be totally honest because I’m not quite sure what god is actually being worshipped there. They’re is some sort of political deist that have put an icing of Judeo-Christian faith around their politically motivated beliefs and written their own sort of 10 Commandments, which begins thou shall always vote Republican and continues on down the line. And somewhere in that 10 Commandments I’m pretty sure it has thou shall attack anyone online who dares to suggest differently. So, that’s the situation we’re in today and unfortunately, these people are all mixed up. I mean in a given church you can have people who take the Bible seriously you could have people who would like to but they don’t even know what it says and you can have people who are entirely living their lives based on their political ideology. No one really knows what being a Christian is anymore today.

Greg Dalton: Yeah. I like that idea, that term political evangelicals rather than, yeah, as much as anything else. We’re talking with Katharine Hayhoe, climate scientist at Texas Tech University and author of the new book Saving Us. I think we often forget, we get so focused on the impact you know that my flying won't do anything. And I think that prevents people from acting if they thought more about the feeling then they would do more because there’s that defeatism that seeps in, you know, individual action let’s be honest, you know, my electric car you're not flying is not gonna say, you know, do it. But there are other reasons to take action.

Katharine Hayhoe: Oh, completely. And action changes us. Action imbues us with a sense of efficacy because we can see the immediate result of the choice we made. It gives us something to talk about with someone else that they feel like they can do too. Like in my book I talk about how I was giving a sermon at a church in Toronto just before COVID actually, and I was talking about all the simple things that we can do and then talk about it. And I was standing by the door, I was listening to people as they walked out and one woman said to another, I’ve always been worried about climate change. I never knew what to do about it so I did nothing. But now I know the first thing I can do. I can eat the Christmas leftovers because food waste is a big part of the problem and it is. So, just doing something, anything, and then talking about it and the next step is, find a group of like-minded people. Whoever you are, whatever you love whatever your passion about wherever you live find a group of like-minded people and connect and join your voices together and advocate for change at every table that you're sitting at. If you’re sitting at a table of the school or at your place of work, your place of worship, your neighborhood, your city, cities have a huge role to play in climate solutions as do companies and corporations. Whoever you are, you have unique access to different circles of influence that nobody else has that exact combination. And that's why using our voices truly is the most important thing we can do to knock over the first domino in the chain that eventually will lead us to a better world. In my book I talk about a man called Glenn who watched my TED talk when it came out in December 2018. And then in May the following year so like barely 6 months later, I was speaking near where he lived. And he took the train to see me speak and he said, I really want to come meet you because I’ve been worried about climate change for a long time. But after I heard your TED talk in December, I decided I was gonna talk about climate change in my town. So, I started to have conversations with everyone I knew about climate change and why it matters to us and what our town could do about it and I've kept a record of those conversations. Would you like to see it? So, I said sure, this was a new one. So, he reached in his leather satchel and he pulled out a sheaf of papers. And I was expecting maybe 70 or 80 names. Well, Glenn had tracked who everybody else I talked to too because he got them to do it too. He now has over 12,000 names in his list and after only five months he had about 10,000 names. And within a year of starting that have a conversation about climate change campaign his city council had voted to declare a climate emergency and which is what they do in the UK, it was in the UK and then they had voted to put 20 million pounds which is a considerable amount for relatively small town towards a climate action plan. And it all began with one man deciding to have conversations using his voice. I mean if he could do that imagine what the rest of us could do.

Greg Dalton: Right. The power of one voice. And UK is one of the leading countries when it comes to commitments under the Paris climate accord. The UK has quite a strong position. You also or now recently, the new chief scientist for the Nature Conservancy. A Bloomberg story last year had this title, “How the Nature Conservancy, the world's biggest environmental group became a dealer of meaningless carbon offsets.” They chronicled how JP Morgan Disney and BlackRock invested in forests to offset their corporate carbon footprint. But the forests were already protected by the Nature Conservancy and not in danger of releasing their stored carbon. TNC was effectively enabling corporate greenwashing. This was before you were there. It's a couple of months before you arrived. As a person devoted to facts and science, what are you doing to ensure such hollow measures don't happen again at the Nature Conservancy?

Katharine Hayhoe: Well, I absolutely am devoted to facts and science. And so, I saw that article before I joined the Nature Conservancy. And that has definitely been the topic of discussions which have showed as you probably know Greg there’s always two sides. And in that case of course we need to be more rigorous with our carbon credits because first of all carbon in ecosystems in the soil is a good thing. And there’s hundred times more carbon there than we humans have put into the atmosphere since the dawn of the industrial era. So, the concept of conserving, restoring, protecting, and in some cases replanting ecosystems to take carbon up from the atmosphere or to prevent it from being released that concept is a valid concept and it’s a really important concept that’s going to help us get to net zero. There is no way to get to net zero without that. But at the same time, you definitely want to avoid getting credit for something you are already doing. But in the case of that Bloomberg article there were some things on the other side that that reporter did not want to consider because he had a story to write and an ax to grind. And unfortunately, and I talk about this in the book, the hardest chapter for me to write but I think the most unusual one for me to write was the one on guilt. The fact that when we are people who have cared passionately about the environment for years. We have a certain perspective on the way it must happen. The way climate solutions must be. And so, we have what Rebecca Huntley, who is an Australian scientist who wrote a great book about talking about climate change last year. We have what she calls a puritan ethos of sacrifice and purity when it comes to issues like climate change. We have a new 10 green commandments thou shalt always do these 10 things and heaven forbid you ever consider not doing one of those you’re only doing them halfway according to my measures because I will turn on you with more vitriol than I reserve for climate dismissives if you do so. So, I posted that on twitter I said, you’re gonna be surprised but I think one of the biggest barriers to climate action is guilt. Well, guess what happened. Not from people who read that tweet from people who just saw me appear on social media. I got guilted and I counted between when I posted that and between 11 AM, which was the last time I saw. I got guilted 12 times.

Greg Dalton: This is what I call the purity police. They’re on you, right. The purity police are after you.

Katharine Hayhoe: I got guilted for writing a book. I got guilted for talking about climate change too much. I get guilted for smiling too much. I get guilted for being doomer too much. I get guilted for what they think I do or don’t eat and what they think I do or don’t plant. And what they think I do or don’t drive they never stop to ask they just automatically guilt. And I mean, I can tell you none of those 12 guiltings made me feel anywhere near remotely like doing more of what I thought I should be doing. It made me feel like digging in my heels and do less. And so, when we circle the wagons and I think it was Obama who actually talked about this quite a bit. When we circle the wagons and sort of start in a circular firing squad when we’re shooting at the people who are really trying to do the right thing and maybe not perfectly up for our standards and it’s always good to call attention to things because we want to be doing this as openly transparently legitimately as possible. But when you don’t listen to what the other person is saying and you just have your view that you’re running with, rather than working together and trying to find common ground we are never going to save ourselves.

Greg Dalton: Well, this is exactly what the fossil fuel companies love because the more people are sniping and judging and sneering at each other, you're not vegan, oh you fly, oh, you do that. The more that pits us against each other and rather than focusing on the concentration of power in the systems and the real things that need to change, right. So, we’re playing right into their playbook.

Katharine Hayhoe: We are and you know what, they are pushing advertising into our social media feeds actually saying this. They’re saying what are you doing to reduce your carbon emissions? Are you driving an electric vehicle? Are you putting solar panels on your home? Have you stopped flying? I said I am holding you personally responsible for 2% of global carbon emissions since the dawn of the industrial era more than the entire country of Canada. And when you have dealt with that, I'm very happy to discuss what I'm doing in my personal life.

Greg Dalton: Well, as we get to the end here. Katharine, I want to ask you, your hope seems to be authentic. And I’m wondering though sometimes let’s be honest that climate is gonna continue to change during our lifetime. It's going to continue to get darker. The science tells us there is already a lot of momentum built up in the system. So, how do you acknowledge that it's going to get worse during our lifetimes. We can do a lot to reduce the harm and still maintain that hope. Do you have to like do you embrace that inevitability and that darkness to get through to genuine hope?

Katharine Hayhoe: You have to. What I’ve learned is that whether you go to theology, philosophy, psychology or science. Hope begins in a dark place. Hope begins with acknowledging just how bad it is. We’re not talking about a sort of a Pollyanna hope or a bury your head in the sand hope or a cultivate a positive attitude and everything will work out okay hope. We’re talking about real hope muscular hope, rational hope. It begins by looking our crisis right in the face and recognizing it is really bad. And as we talked about at the beginning it’s probably worse than scientists say. And there is no guarantee of a positive outcome. In fact, a negative outcome is more likely than a positive one. But hope is that faint small bright light at the end of the dark tunnel, that we head for with all our might and all our strength and when we get dragged down when we get discouraged, when we get anxious and depressed, and believe me that happens to me too. We take a breath, we fix our eyes on that hope by going out and looking for what someone else is doing, or by making a choice to do something myself and then we pick ourselves up and we keep on going because what is at stake is too valuable to lose. It's not our planet itself; it will orbit the sun long after we’re gone. What’s at stake is literally us. So, I think of Christiana Figueres, who of course shepherded the Paris agreement. If anybody could be hopeless, despondent and frustrated it’s her. Yet, she wrote this amazing hopeful book of what our lives would look like by 2030, with climate impacts. But if we had transitioned to clean energy, walkable cities, clean air, cheap electricity, ample food for all and she said, look at this amazing vision of the future. The biggest lesson we learned in 2030 looking back, was that we were only ever as doomed as we believe ourselves to be.

Greg Dalton: Katharine Hayhoe thank you again for sharing so much of your dynamic insightful insights on Climate One.

Katharine Hayhoe: Thank you for having me, Greg.

Greg Dalton: On this Climate One... We’ve been talking with Katharine Hayhoe about hope and healing. Climate One’s empowering conversations connect all aspects of the climate emergency. To hear more conversations, subscribe to our podcast on Apple, NPR One or wherever you get your pods. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. It really does help advance the climate conversation. Brad Marshland is our senior producer; Ariana Brocious is our producer and audio editor. Our audio engineer is Arnav Gupta. Our team also includes Steve Fox, Kelli Pennington, and Tyler Reed. Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.