Jane Goodall in Conversation with Jeff Horowitz and Greg Dalton

Guests

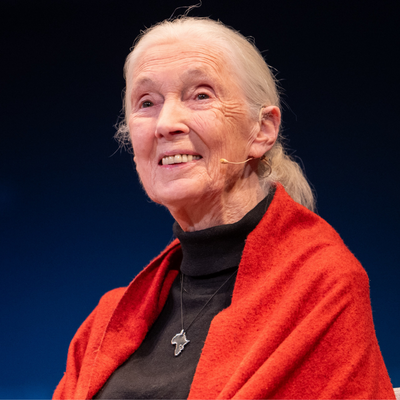

Jane Goodall

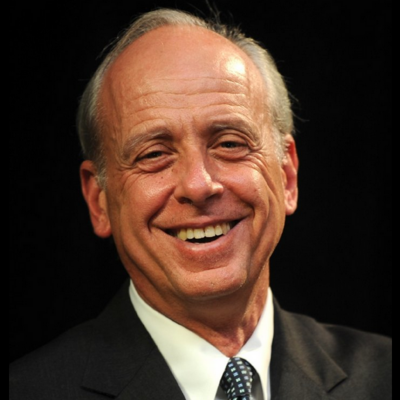

Jeff Horowitz

Summary

Noted conservationist Jane Goodall talks about her life’s work, the link between deforestation and climate change and why she sees reasons for hope.

Jane Goodall, Founder, Jane Goodall Institute; United Nations Messenger of Peace

Jeff Horowitz, Founder, Avoided Deforestation Partners

This program was recorded in front of a live audience at the Commonwealth Club of California on April 3, 2017.

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: From the Commonwealth Club of California, this is Climate One, changing the conversation about America's energy, economy and environment. I'm Greg Dalton. My distinguished guests on the show today are environmental icon Jane Goodall and film producer Jeff Horowitz.

[Applause]

When Jane Goodall was a child her father gave her a stuffed chimpanzee doll named Jubilee. At the age of 26, she went with her mother to study chimpanzees in Gombe Stream National Park on the coast of what is now Tanzania. She had no college degree and no field experience. She later earned a PhD at Oxford and became famous around the world as a pioneering scientist and the foremost expert on our chimp cousins. It’s been said that she redefined humanity. Today, she is United Nations messenger of peace and she travels the globe spreading her vision for a healthy balance between people, animals and the environment. Jeff Horowitz is an environmental activist and film and television producer. With James Cameron and Arnold Schwarzenegger he is a co-executive producer of the Years of Living Dangerously, a TV series and Emmy award-winning TV series on climate change. He is an advocate for protecting the earth's forests and he is also a contributor to Climate One. Please join me in welcoming Jane Goodall and Jeff Horowitz.

[Applause]

Dr. Goodall you travel the world 300 days a year and recently at one point you were in Greenland and you had an encounter about climate change. Share with us that moment.

Jane Goodall: Well, it was really when the reality of climate change kind of viscerally hit me because I was with some of the Inuit elders and we were by the great ice cap, and they were crying and they were saying even in the summer the ice here never melted. And there was just water pouring out of this great ice cliff and the icebergs were carving and it was really, you know, and then I happened to be going straight from there to Panama and there I met some of the indigenous people who'd already been moved off their islands because of the melting ice; the sea levels were already rising and they’d had to leave because at high tide their homes were endangered. And that just hit me from one to the other as though the fates had taken me from this place to that place to see A, what was happening and B, the effect it was having.

Greg Dalton: So you knew about climate change before but being there in that moment with those people made it different, it got to your heart in a way that knowledge didn't.

Jane Goodall: Exactly, sometimes it just really hits you.

Greg Dalton: And what have you done with that afterwards with that impact? What did you act upon that knowledge?

Jane Goodall: Well, first of all learning all that I can about it and reading some of the scientists’ reports, and travelling around and then all the lectures I give and I don't know how many hundreds per year all over the world. I talk about it, you know. It's not the main topic of my lectures but it's something that I always bring in as the greatest threat that we face right now.

Greg Dalton: Jeff Horowitz, how do you have your climate awakening -- you’ve been into forests, you are a trained architect, how did you come to this climate conversation.

Jeff Horowitz: Well, first Greg, I'd like to acknowledge you and the fact that you invited us and you're doing incredible work by having this program.

Given the news that we've all heard in the last several days not even weeks or months, your work here is more important than ever and I want to just have everyone acknowledge the fact that you’re doing a great work.

[Applause]

Greg Dalton: Thank you.

Jeff Horowitz: Now, as far as Jane is concerned most of you have probably known of Jane for the obvious chimpanzee work that she's done but very few of any of you probably are aware of the fact that Jane has with us and others attended almost every major international climate change negotiation and meeting around the world from Copenhagen to Durban to Rio to Paris when the climate talks came together with an agreement. It's very important to understand that people like Jane are looking beyond what they're accustomed to looking at and it's my job and others to try to get her outside of her comfort level by basically meeting with people that she wouldn't ordinarily meet with, like heads of state, like heads of the World Bank.

If you look at the footage of the major climate walk that was done, the march that was done just a couple of years ago in New York City, you will see Ban Ki-moon at the front of that massive crowd and right next to her, him sorry, is Jane Goodall leading the way on climate. So from that point of view having her here and having her be a part of the community of people that are looking for solutions, I commend Jane for being here and I want to thank her for her service to helping with the climate solution.

[Applause]

Jane Goodall: It was this man who dragged me out of my comfort zone to all these things, this very man.

Jeff Horowitz: We all have our missions in life, what can I tell you.

[Laughter]

I had a very pedestrian entrée to climate change. I was one of the 8 million or so that saw an inconvenient truth and living in the bay area it's very hard not to get swept up in something that was so profoundly visceral in terms of getting us to all collectively as a world understand that climate change is such a serious problem. And in fact, it's almost the uber problem that we all need to tackle because so many other things follow as a consequence of climate.

So I became one of the converts and that coincided with a group that was founded by a nephew of mine who wanted to tackle the issue of deforestation, not understanding that at the time deforestation accounts for as much carbon pollution as all the cars, trains and planes in the world combined. Now, as much as Al Gore was something of a hero to me, the fact that it wasn't mentioned was something that was a bit alarming to me. And that's where we started our organization to basically galvanize individuals like Jane and others, business leaders, country leaders, NGO leaders to all work together and play a bit of catch up so that the whole idea of the forest connection to climate change would be just as front and center as the power sector is when it comes to understanding this issue. Thank you.

Greg Dalton: Years of Living Dangerously is an eight-part series that uses celebrities to convey the importance of climate change and solutions and we’re going to show a clip of one of those segments with Harrison Ford walking through a grocery store connecting palm oil, which is a forest issue, to many of the foods on the grocery store that we -- let’s listen to this clip. He is talking to Lafcadio Cortesi from the Rainforest Action Network.

[Start Clip]

Lafcadio Cortesi: Snack food, cereals, cakes, processed foods, candy bars, cookies, cheeses, Oreos, soaps, shampoos; it’s pretty much on every aisle of most supermarkets. You will find palm oil in there.

Harrison Ford: Palm oil comes from the fruit of oil palm trees. Lafcadio Cortesi of Rainforest Action Network tells me that almost all those palm trees are grown on land that used to be forest.

Lafcadio Cortesi: It's not the oil that's bad; it’s how the oil is produced. Companies need to find out where their palm oil is coming from and they need to make a commitment, we’re not gonna contribute to climate change and deforestation and then look at their supply chains and prove that.

Harrison Ford: Lafcadio says demand for palm oil is growing faster than any other agricultural commodity. And in Indonesia, that means even more incentive to destroy forests. I'm going there to find out more.

[End Clip]

Greg Dalton: That’s Harrison Ford in Years of Living Dangerously. So Jane Goodall help us understand palm oil, the connection with all those food that they mentioned on their grocery store shelves to habitat and places you study.

Jane Goodall: Well unfortunately, more and more areas of old-growth forests which are, you know, these centers of biodiversity and for me a rainforest is a really spiritual place where you understand the interconnection of all life forms and the importance that even a small species can play in this whole web of life and these amazing rainforests being cut down to grow palm oil plantations.

And I've flown over in Indonesia and seeing the terrible destruction it’s just miles and miles and miles and miles of palm oil plantations and it’s spreading to other parts of the world, to all over Malaysia now, then it went into other parts of Asia to Latin America. It's now arrived in Africa. And so as these forests to cut down then we’re, you know, this is partly responsible for the era we’re in, the sixth great extinction. It's devastating to the orangutans and other primates in Asia but now it's going to affect the chimpanzees in Africa too.

Greg Dalton: Is there such a thing as sustainable palm oil? Companies are trying to respond to this saying they’re doing better practice rather than denuding the world. Is there such a thing as sustainable palm oil?

Jane Goodall: I had a long talk with people who are really in the cutting edge of this research in Malaysia. And they said, well it is possible because you simply grow it where the forest has already gone. But for a grocery store that's trying to do the right thing, the chain back to where the palm oil in the product came from is very, very difficult, but they're working on it.

Greg Dalton: Jeff Horowitz, some consumer product companies, Unilever, Nestlé, et cetera are working on this. Are they really doing the right thing or are they just trying to green wash us on this sustainable palm oil?

Jeff Horowitz: You know, that’s a great question because most people just by nature don't trust companies. Companies are not people, right? But the fact of the matter is, companies really have no choice. We are living in a world where we’re a little over 7 billion people and by 2050 they project that we’ll be at 10 billion people.

We now have the need for three planet earths in order to sustain the food and the other stuff that people buy on a regular basis. Companies know that they need a reliable supply chain. So if they don't move to more sustainable sources, they’re screwed. It's a good thing that they’re screwed because it helps us and that is the only, really the only reason, why companies are moving in the direction of going green. Now, as far as leadership is concerned, there was a group that got together, it was a hundred CEOs and they banded together to create what's called the consumer goods forum. They control $3.1 trillion worth of consumer goods. And it finally dawned on them that if we don't stop this destructive deforestation thing as part of this supply chain, then everyone's out of luck. So they declared to all of their suppliers that by 2020 they want to see a dramatic reduction in their suppliers’ use of land that comes from forests. In other words, they want to create a new paradigm in the marketplace to say that deforestation free goods has to be the norm.

Greg Dalton: Jane Goodall, we’re talking about diet. Diet is a big lever when it comes to climate. Some people say what you eat is more important than what you drive. What is your diet like and how can people who are concerned about climate have a climate-smart diet?

Jane Goodall: Well, glad you asked that question because I was determined to talk about it even if you didn’t.

[Laughter]

So I think from about the late 60s I stopped eating meat. Now, I stopped eating meat because I learned about the intensive animal agriculture and these terrible factory farms.

Next time I looked at meat on my plate I thought this symbolizes fear, pain and death. So I stopped eating it. Then I began to realize a lot more that as nations around the world become wealthier, they eat more and more meat. It becomes a status symbol. And so what's happening is these billions of animals in these awful conditions, they have to be fed, rainforests are being cut down to provide the grain, huge amounts of fossil fuels are burned getting the grain to the animals, the animals to the abattoir, the meat to the table. Huge amounts of water are being wasted to change vegetable protein to animal protein. I've been in many parts of the world where the grazing of cattle moving deeper and deeper and deeper into the forest, change it to woodland and eventually into some kind of inhospitable habitat which wouldn’t support life. And then, you know, if people don't care about animal welfare, okay, they don’t care about the environment, okay. They probably care about their own health and I happened to be in the U.K. when the surgeon general made this chilling announcement that the era of the antibiotics is nearly over and a main contribution is the misuse of antibiotics keeping these animals alive.

And then the final thing which impacts directly onto climate change and these so-called greenhouse gases that circle the planet and trap the heat of the sun. You know, a very vicious greenhouse gas is methane and I usually carry around with me a little stuffed toy, a cow, and I point out especially to the children that, you know, you hold up the cow, food goes in the mouth and gas comes out the end and that’s methane.

And so the intensive animal husbandry is causing a huge, huge amount of production of methane.

Greg Dalton: A lot of people can agree that factory farming is bad, people here in Northern California like to think that pasture-raised, grass-fed beef or poultry that that somehow more humane and virtuous and has less of environmental impact. Do you see that case?

Jane Goodall: Well, certainly for the animals it's much better. For the environment and our future, I'm not sure because -- but it would mean, you know, it costs more to get that kind of meat or eggs and so forth. And that means that people will start thinking a little bit more, okay, it costs a bit more to buy an egg that comes from a hen that was free. So you don't waste as much. Think of the food that we waste. Think of, I mean, you go into restaurants, go to Texas, see the piece of meat that’s dumped on people's plates.

Greg Dalton: What, you don’t want to go to Texas?

[Laughter]

Jane Goodall: Well then, so half of it is thrown away. That's the point.

Greg Dalton: So you’re not against eating animals ever, it’s just how it's done, done more mindfully, more respectfully.

Jane Goodall: Well, I personally don't want to eat animals, personally.

Greg Dalton: But you understand other people --

Jane Goodall: So rather than just say all or nothing which doesn't of cause change, it's better to just go step-by-step. But the main thing is it made people think about it. And if people haven't been to an abattoir, I would advise them not to go because you’d have nightmares for weeks. So, you know, there are all of these different issues.

Greg Dalton: The slaughterhouse.

Jane Goodall: The slaughterhouse.

Greg Dalton: Jeff Horowitz, how have you changed your diet?

Jeff Horowitz: My wife is in the audience maybe she can help with the answer to that one.

Greg Dalton: Yeah.

Jeff Horowitz: I think -- look, we just did a story in Brazil on beef and the fact is that right now at this moment in time, the Brazilian Amazon is once again being destroyed, principally because of this enormous interest in eating more and more beef. 65% of the Brazilian Amazon is going up in smoke. As people take a bite out of their burgers, it takes a bite out of the rainforest. I think all of us, especially in the bay area, who do like beef from time to time have simply cut down on how much we eat. I don't think it's a hard thing to make a simple choice in a restaurant where you say we want to avoid some foods when in fact beef and beans have the same amount of protein, but beef is 20 times the carbon footprint of beans. So it really doesn't take a lot to occasionally make that little choice, turn away from something that you know is harmful for your own health in addition to the planet’s health.

Jane Goodall: I have to put a funny joke in there that beans, I'm told by some people do make us produce more methane gas.

[Laughter]

Jeff Horowitz: So that’s the reason why I --

[Laughter]

Thank you, Jane.

Greg Dalton: If you’re just joining us, today we’re talking at Climate One at the Commonwealth Club with Jane Goodall and Jeff Horowitz. I'm Greg Dalton. Jane Goodall, you write a lot about empathy and I’d like to know, you know, empathy for the chimpanzees that you studied, can you summon empathy for poachers and people doing environmental degradation?

Jane Goodall: I absolutely, you know, it depends. There’s poachers and poachers.

If we’re talking about the international animal trafficking where people come in with helicopters and, you know, machine guns and kill elephants for their ivory, no sympathy, none at all. However, having seen for myself the poverty in Africa in and around the rainforests where the chimpanzees live that we’re trying to protect, you know, if you’re very poor you’re going to kill an animal because you need to eat it and you don't have money to buy anywhere else. And if that animal happens to be in a protected area then you’re labeled a poacher. If you happen to be out of a protected area, it's called subsistence hunting. And so, you know, but this goes beyond that simple we got to kill to eat. And it -- when I flew over Gombe National Park in 1991 and looked down on this tiny 30 square miles of forest, which used to be part of the great forest belt, and saw that it was surrounded by completely bare hills with more people living there than the land could support, too poor to buy food from elsewhere and living and struggling to survive and that's when it hit me we can’t even try to save the chimps in the forest unless these people can have better lives, because if you’re starving, of course you cut down the last trees to try and grow food or to make charcoal. And it's the same thing. This necessity to alleviate poverty comes right through into the developed world, because if you are very poor in an urban area, you’re going to buy these very cheap foods because you have to, you’ve got to feed your family, you can't afford to look and buy the expensive organic products or the ones that come from, you know, palm oil-free products.

So alleviating poverty to me is a very, very important part of changing, slowing down climate change.

Greg Dalton: Let’s talk about some of the bright spots. You travel the world and climate change is often seen as doom and gloom, there is a lot of alarming things happening, it's here, it's now. But Jane Goodall, you travel the world, where are some positive stories, really bright spots that you see where positive changes happen?

Jane Goodall: Well, of course, I can't resist saying that we’re having this long discussion about climate change, but it's a hoax, it was invented by the Chinese right?

[Laughter]

So I don’t know why you have this program at all, but anyway.

Greg Dalton: So we should just talk about something else.

Jane Goodall: No, there are a lot of bright spots. This is it. I mean, people say Jane you can’t really have hope because you’ve been around, you’ve seen the destruction of the forest, you’ve seen animal species decreasing in number, you’ve seen the poverty and, you know, all the rest of it. But at the same time, I’ve seen incredible projects, I’ve met the most amazing people who are doing things to really make change, and we do need changed attitudes. But I described flying over Gombe and seeing 30 square miles of forest surrounded by bare hills because we began working with Jane Goodall Institute with the local people to improve their lives in a holistic way. There are no bare hills anymore. The trees have come back and the chimpanzees have now more forest than they had and we’re protecting other areas where the forest hasn't yet been cut down. So this is one bright spot, that bright spark that you're talking about. But, you know, travel around the world and see the incredible advances that are being made in ways of living in harmony rather than destroying nature, listening to nature, biodynamic farming, organic farming, small-scale family farming.

Even the United Nations have said the best way to feed the growing population is small-scale family farming, not these monocultures, and please let’s eliminate genetically modified food. Let's eliminate some of these chemical pesticides, herbicides and fungicides that are being proven to be harmful not only to the environment but to our health, our children. You’ll hear, we haven't inherited this planet from our parents, we borrowed it from our children, we haven't borrowed our children's future. We've stolen it and we’re still stealing it and we’ve got to get together and do something about it if we care about our children and our grandchildren.

[Applause]

Greg Dalton: And speaking of children you have some thoughts about population as a driver beneath all of these things that we’re talking about. What should be done about population?

Jane Goodall: For a long time it was considered politically incorrect to even mention it and most of the big conservation organizations refused to mention it. But I always thought, I mean, you see what happens. In the old days, there were cultures and a lot of these indigenous people and you had lots of children because they looked after you in your old age and you shared out the land. But now it's different and they know it's different. And that's why there were bare hills all around Gombe. So we've introduced in our program, we’ve introduced family planning so welcomed by the people because they know that things are different. And of course, this administration is cutting family planning around the developing world which is terrifying to me.

And so if you approach family planning right, it’s something that's very, very important. And when it was considered politically incorrect to mention it and I was determined to mention it, I decided to call it voluntary population optimization.

[Laughter]

So by the time people worked it out --

[Applause]

Greg Dalton: And research shows educating girls is one of the smartest things --

Jane Goodall: Yeah, I meant to say that, yes indeed. Women's education, empowering women and scholarships to keep girls in school beyond puberty. Family size then tends to drop worldwide indeed.

Greg Dalton: If you’re just joining us our guests today at Climate One at the Commonwealth Club are Jane Goodall and Jeff Horowitz. I'm Greg Dalton. We’re gonna go to our lightning round, a time for brief questions and one word or one phrase answers. So true or false. Jane Goodall, most humans won't give up their material comforts to limit environmental harm.

Jane Goodall: I can just say true or false?

[Laughter]

True.

Greg Dalton: Jeff Horowitz, you would get into a small plane piloted by Harrison Ford.

[Laughter]

Jeff Horowitz: True.

Greg Dalton: Jane Goodall, you would get into a small plane piloted by Jeff Horowitz.

[Laughter]

Jane Goodall: False.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: Also, Jane Goodall, hunters are some of America's strongest conservationists.

Jane Goodall: False. Totally.

[Applause]

Greg Dalton: True or false. Jeff Horowitz, you've eaten red meat in the last 30 days.

[Laughter]

Jeff Horowitz: True.

Greg Dalton: True or false. Jane Goodall, girls just want to do science.

Jane Goodall: I don’t know. False.

Greg Dalton: Jane Goodall, you hug and kiss like a chimpanzee.

[Laughter]

Jane Goodall: True.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: All right. We’re gonna move on to association. I’m going to mention a word and you’re going to mention what comes to your mind from your heart without any filtering; the first phrase or word that comes to your mind. Jane Goodall, zoos.

Jane Goodall: Prisons.

[Applause]

Greg Dalton: Bigfoot.

Jane Goodall: I can’t think of the right word. It's exploration, it’s excitement, it’s possibility, it’s romance. It's all of those things.

Greg Dalton: Jeff Horowitz, EPA chief Scott Pruitt.

Jeff Horowitz: Thug.

[Laughter]

[Applause]

Jane Goodall: That’s much easier. You give him easy ones.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: Jeff Horowitz, sustainable meat.

Jeff Horowitz: Impossible burger.

[Applause]

Greg Dalton: Which is a plant-based food made here in Oakland. Jane Goodall, your favorite drink.

Jane Goodall: Whiskey.

[Laughter]

[Applause]

Greg Dalton: That didn’t take very long. That came from -- yeah, it’s true.

Jane Goodall: My voice.

Jeff Horowitz: Yeah, it’s through her voice.

Greg Dalton: She put in her cup to hide it. Last one. Jane Goodall, Donald Trump.

Jane Goodall: I cannot tell you because somebody might publish it.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: All right. That ends our lightning round. Let’s give them a round. Thank them for that.

[Applause]

Greg Dalton: Jane Goodall, as a pioneer in science who broke some glass ceilings, what advice do you have about girls who are interested in science, technology, engineering, math, STEM careers?

Jane Goodall: I think -- I always tell young people what my mother told me when I wanted to go to Africa and live with wild animals and write books about them when I was 10 years old. Everybody laughed at me and said, well you don't have the money, Africa is far away, the world is -- World War II is raging and you're just a girl. Dream about something you can achieve. But what my mother said to me was, if you really want to do something you’ve got to work very hard, take advantage of opportunity and never give up. So what I tell girls who want to pursue some career in science, it's not that easy and you’ve got to really want to do it. If you really want to do it, just go for it, work hard and never give up.

Greg Dalton: Pretty good advice.

[Applause]

And we have a number of children in the audience here today. We’re talking about a very serious topic climate change.

Oftentimes, it’s delicate to talk about climate change with children. How do you speak to young people about something that they’re going to live this future more than the three of us are? How do you communicate climate change to young people in a way that’s not scary?

Jane Goodall: I tell the children stories but, you know, we have a program for young people called Roots & Shoots which has members in 98 countries and it’s kindergarten, university and everything in between. And so what I tell the young people is to explain the problem and then ask them to get around and think about what they could do. It's absolutely amazing what children can think of to do to mitigate climate change. So I think you explain the problem, it can be a bit scary, but then you say to them that, you know, there’s something every single one of us can do about it every single day.

And you may feel, adults too, that the problem is so huge, what can I do, I wouldn't make any difference. And if it was just you in your ordinary life you wouldn't make any difference. But when you have billions of people thinking about the consequences of the choices they make, whether it's what they eat, what they buy, what they wear, you know, where did it come from -- how is it made, then billions of ethical choices move us towards the kind of world we need and that includes problems about climate change.

Greg Dalton: Jeff Horowitz, you’ve helped produce some of the most impactful media and journalism on climate change, Years of Living Dangerously, A Time to Choose with the Academy award-winning director Charles Ferguson; and yet TV coverage of climate fell last year. How is the media doing in terms of making this an important issue in getting through, lots of documentaries? Is it really breaking through and moving the needle in terms of American public opinion?

Jeff Horowitz: It's awful. I mean, that's the only word I can use. If you think about it, climate change didn't even come up as a question through the presidential debates. Not once. Not for any of the debates. The fact of the matter is that we have in the media world very formidable foes. The oil and gas industry has absolutely endless resources. These are the top 10, you know, richest companies in the world. It is very, very easy for them to come up with a unified message, invest in oil or buy oil or, you know, use -- oil and gas companies are creating the jobs, they are the ones that are the future and the environmental groups have to pick up sort of the scraps of what we can all hobble together, all of us, and try to come up with messages that combat those very, very big, powerful companies. The fact of the matter is, there’s something really amazing that happened this last year. This past year for the first time, it is cheaper to go green in terms of your energy. In other words, wind and solar are now cheaper then dirty fossil fuels.

[Applause]

It is astounding despite the fact that these messages are hard to get out, you can easily look at your pocketbooks and say this is working, this is the future and to hell with the large companies that are doing gas and oil exploration around the world. Thank you.

[Applause]

Greg Dalton: You both have a relationship with National Geographic. Jane Goodall, what did you think when you’ve learned that Rupert Murdoch bought National Geographic?

Jane Goodall: Well, I must say I was shocked and horrified, but I also have to say that the additional funds that have been pumped into the Geographic is actually turning it around and it's able to do some pretty remarkable things. So, you know, the fact that Richard Murdoch bought it is one thing, the people who are now within the National Geographic organization, they are the ones who are going to make the difference.

Greg Dalton: Jeff Horowitz, any thoughts on that? A lot of people thought, oh that’s gonna be bad. Maybe it hasn’t turned out as bad. There was a sinking ship in many ways and now it's more stable perhaps.

Jeff Horowitz: National Geographic has been really amazing to work with on the issue of climate change. They want to keep doing more and more programming on it and anytime we can find an outlet that is as reputable and high quality as National Geographic we’re pleased as could be. So thank you.

Jane Goodall: I've been doing programs with them about various environmental issues in different parts of the world because Geographic has offices everywhere and they’ve just made a retrospective of Jane Goodall. We’re using footage which was never shown before from, you know, they’ve got miles and miles of footage and that's coming out quite soon.

Greg Dalton: I watched a little trailer for that. It’s quite amazing watching you as a young woman climbing trees very early in your career. You said something earlier that, you said you were -- well, you wrote a book called Reason of Hope: A Spiritual Journey, you've lived through the London Blitz, you’ve been taken hostage, you watched your husband die slowly from cancer and yet you say you were lucky to be born during the war. So tell us about that reason for hope in your journey.

Jane Goodall: I was lucky to be born during the war because in the U.K., in England, we were rationed. So, I mean, I think we got something like one square of chocolate a week, if we were lucky we got one egg a week.

Clothes were all in coupons. You have to save up coupons. Books, well, we didn't have much money anyway and so books came from the library or you saved up a few pennies for secondhand books. So as a result of that kind of upbringing, I don't take stuff for granted. You know, it took a long time before I could understand that buying a bar of chocolate was something that you could actually do. It seemed like exotic. So that’s I think why today I can live in a very simple way and not take stuff for granted and appreciate what I have rather than being miserable about what I haven’t.

[Applause]

Greg Dalton: You travel what, 300 years -- 300 days a year --

Jane Goodall: 300 years a day.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: It feels like that. How do you remain so calm and travel, live on an airplane?

Jane Goodall: I think it's because I spent all those years in the forest on my own and I've already said I just hope that sends a great spiritual power. And so, it's quite easy for me to withdraw from where I am and just go into myself and still feel that peace. That peace is there. And as I'm travelling around the world I always try and take a few moments when I can to be in some kind of nature. And in fact, nature, being in green places is very, very important for all of us. And it's being proven now that the children's psychological development they need to be out in green places and so many children don't have that opportunity. And then now they’re all on their little video games and taken away from nature and it’s doing harm.

Greg Dalton: If you're just joining us our guests today at Climate One at the Commonwealth Club are the ecologist Jane Goodall and the film producer Jeff Horowitz. I'm Greg Dalton.

This is a book that a middle school teacher gave to me yesterday. This was sent to 40,000 middle school science teachers around the country and Jane Goodall I’d like to ask you, it says that this person writing from the Heartland Institute for the Center for Transformative Forming Education says that science on climate is not settled and that we need to do more research to decide if climate is happening and whether or not it should be worried about. As a scientist, what do you think about this and what can be done about this really direct misinformation sent to 40,000 schoolteachers?

Jane Goodall: Well, you know, you just told me about it and it's absolutely shocking. And it's because of this administration that something like this can go around and I don’t know what we can do about it but I think we have to bring it into the open. We have to have discussions about it and coming out on your program like this is something, it's very important because the science -- it's not true what they say. It's a whole lot of hogwash.

Greg Dalton: We’re going to go to our audience questions in just a minute. But I've been working at the Commonwealth Club for 16 years; I often get asked who is the most amazing speaker in that time. There is no one amazing one, but there is a top five moment that I remember 14 years ago when Jane Goodall spoke to a group in San Jose and she held up a glass of water and talked about it in a very eloquent way that stayed with me for all these years. So I'd like you to look at this glass of water and tell us the beauty, what you see in that.

Jane Goodall: Well, what I see here is a glass of clean water that I can drink and that you go to a restaurant and people will fill up your water and then what happens to it because you don't always want it. And we treat water as though it's just something that's our right. And there are so many parts of the world where this amount of clean drinking water would be prized beyond the most expensive glass of wine or even whiskey.

[Laughter]

And the shocking thing to me is the way that we in the developed world we waste this precious, precious commodity. One of the awful things is that all over the world fresh water supply is shrinking, the aquafers are getting lower. But the pollution from the runoff of agricultural and household and industrial waste into the rivers and then into the sea, polluting the sea, creating acidified areas so that the ocean is the other great lung of the world along with the rainforest, and as we pollute the ocean, we’re also contributing to climate change.

So I'm sure I'm not as eloquent now as I was then but to me this little glass of water is, you know, it is just so, so important that we don't take it granted. We don't waste it. And we see it as the lifeblood of people who have no clean water available to them. It's precious.

[Applause]

Greg Dalton: Thank you. This is Climate One from the Commonwealth Club. I'm Greg Dalton. And my guests are Jane Goodall and Jeff Horowitz.

Let’s go to our audience question.

Female Participant: I was wondering what is it like to be friends with chimps and how is it alike or different than being friends with people?

[Laughter]

Jane Goodall: Well, it’s different. But out in the wild we respect the chimpanzees, we watch them. They allow us to follow them and write down what they're doing. They allow us to film them. When I first went to Gombe it was very different because first the chimps ran away from me and then I managed to get closer, and in a way they really were friends. David Graybeard allowed me to groom him, tickle him and play with him. And that's more like friendship. But now we know that chimps can get our diseases, we don't touch them anymore. So it's different.

A human friend has to be different because we can speak to them, we have the same language and we’re more alike than humans and chimps even though chimps are more like us than anything else. But they’re wonderful.

Greg Dalton: Next question up on the balcony. Welcome to Climate One.

Female Participant: Hi. That was a great segue to my question which is in a time where we are actually really divided as a country where we do speak the same language but it doesn’t really feel like we do, how would you suggest communicating things like the importance of accepting climate change to Americans who don't want to acknowledge it in an empathetic way?

Jane Goodall: I think the only way is telling stories and not arguing, not becoming aggressive and I think if you speak to people in not in an angry way but by trying to share what you know in a way of telling stories like the story I told about Greenland and Panama. And that's one of the messages we have for our youth groups, our Roots & Shoots. If I could see you all here which I can’t really, but I'm sure there are people with different colored skin; I’m sure there’s different cultures and different religions and yet we’re all part of one human family and we now know from the DNA analysis we are truly one human family. And if we cut ourselves the blood is the same. If we cry, our tears are the same. If we laugh, we laugh from the same kind of emotion. And so we may look different and sound different, but we’re one family. And that's something that’s really important. We need to learn to live in peace and harmony between nations, between cultures, between religions and between us and the natural world.

Greg Dalton: Jeff Horowitz, anything to add as a media person producing film and television to reach people who haven't been reached yet.

Jeff Horowitz: You know, I wish I knew that secret because the fact of the matter is when An Inconvenient Truth first came out it was so revelatory, it was so startling and it was such a shocking moment for all of us. The one thing I can say is that it did jumpstart this amazing movement around the world. And whether you like Al Gore or you don't, it doesn't really matter at this point. It's really taken hold. I think it's been very hard to follow in that wake. In fact, I think that his own sequel will probably be not nearly as powerful as the original. So I think we just have to keep looking for different ways to find a way to get these messages out and every little bit helps, this show helps. I'm sure there will be other people who will percolate with other ideas.

Greg Dalton: We’re talking at Climate One with the film producer Jeff Horowitz and the scientist Jane Goodall. Let’s go to our next audience question.

Male Participant: Hi. Jane, when you’re an icon you’re gonna have a lot of legends around you and I heard a legend that you observed the chimpanzees for 10 years before you saw them eating meat. Is that legend true and do you think that they’re naturally herbivores and what do you think humans are?

Jane Goodall: Okay. It's true that chimpanzees do hunt, not very often; it's about 2% of their diet apparently in a year as the people studying chimp diet have announced. They are very excited with the hunt. Meat is very precious to them. What are we? Well, we’re omnivores and the great thing about meat-eating is that there are two kinds of gut apparently. This is not my specialty. There are carnivores like the lions and they have a very short piece of gut because they want to get the remains of the meat out quickly before it putrefies in your inside. And then there are the herbivores and they need a long gut to get all the goodness out of the leaves and grasses and things that they eat.

We have the herbivore type of gut not the carnivore type of gut.

Greg Dalton: Let’s go to our next audience question up in the balcony.

Male Participant: Hello, Dr. Jane Goodall. Thank you so much for coming. My question to you as an ecologist, you helped us all redefine what it means to be human and I thank you so much for that, but what do you think are some of the next questions we need to redefine? What are the new terms or words we need to redefine?

Jane Goodall: Well, I don’t know about redefining but I actually believe that right now for anybody interested in studying animal behavior, it is the most exciting time certainly in my lifetime because, you know, when I got to Cambridge University and was told I couldn't talk about chimpanzees having personalities, minds and emotions because they were unique to us and it was thought that there was a sharp line, a difference of kind between us and the rest of the animals, and the chimps helped us to understand that in fact we’re part of the animal kingdom but the scientist were still -- although they were admitting yes chimpanzees were very intelligent, elephants and dolphins and things like that but birds, no. When parrot owners say my parrot understands what words he is saying, they’d say no because the bird brain is structured differently. Now it's been proven that birds are incredibly intelligent. You can look up the experiments with crows in Oxford University. Now there’s a whole flurry of interest in the octopus. The octopus doesn’t even have a proper brain. It’s got a central nervous system. And so what the octopus can do running across the ocean bed with two halves of a coconut shell creeping into one-half, putting the other over its head. So it’s made a house where there are no rocks. And, you know, the latest thing was bumblebees.

A bumblebee can be taught to roll a little ball and put it down in a hole and other bumblebees who’ve just watched that can do the same thing to get a reward. Trees can communicate. There’s so much out there. So it's really redefining how we think of ourselves in comparison with the rest of the animal kingdom. We’re just one part of it and we've gone wrong. We’re the most intellectual and yet how is it possible that such an intellectual creature is destroying its only home. This is the question we have to answer and address.

[Applause]

Greg Dalton: Let’s have our next question for Jane Goodall and Jeff Horowitz.

Female Participant: Hi. I’m Lila Hudsler [ph] and I’m really excited to be here tonight. I mean, you are my hero. I have like all these books about you. You’re really inspiring to me and my friends. And my question is because if a chimpanzee could say one thing about like -- about the environment where it lives and it had one lesson to teach us, what do you think that would be?

Jane Goodall: I think the chimpanzee would say stop destroying my home. The home is the forest. We’re destroying the forest every day and that means that chimpanzees are being pushed towards extinction. So I think the chimpanzee would say, please this is my home, I love my home like you love yours, please stop destroying it.

[Applause]

Greg Dalton: Next question.

Female Participant: Hi, Jane. I’m a college student studying ecology and evolutionary biology and hoping to go into wildlife conservation especially hopefully with non-human apes. And I was wondering what you think the most important skill for people like me is to learn to really make real change and be effective in doing so.

Jane Goodall: I think that you need to and it sounds as though you have a real passion for doing what you want to do, you have to be prepared to go out there not just to say I'm going to discover this about this animal, but to say I'm going out to be with that animal to learn from that animal, not just about that animal. I need to learn from that animal and to be prepared to open your mind and not be afraid of what other scientists might say. And above all, have empathy, just have empathy and feel what that animal feels and then ask questions.

Greg Dalton: We have time for two more questions. The next one is down here.

Female Participant: I was part of Roots & Shoots when I lived in London and I was a student of Wendy Diamond, one of your close friends. I remember the group very well and I’m working on setting up Roots & Shoots here. Do you have any suggestions for what we could do? And one of my other questions is, why did you start Roots & Shoots?

Jane Goodall: Well, I started Roots & Shoots because as I was traveling around the world I was meeting a lot of young people who seemed to have lost hope and who said that we compromised their future and there was nothing we could do about it.

I've already said we've compromised your future, but I don't believe there’s nothing that can be done. So we had this gathering of Roots & Shoots initially in Tanzania with the main message, every single one of us makes an impact on the planet every single day and we have a choice as to what kind of impact we’re going to make. And we decided because of everything -- I always see the interconnection between things that each group would choose projects to make the world better for people, for other animals, for the environment we all share.

And so Roots & Shoots doesn't dictate to young people what they should do. It simply says, what do you care about. Sit down and discuss it with your friends and choose a project to address that concern that you have. So the projects are going to be different depending whether you’re in a city or a rural area, a rich country or a poor country, it will depend on perhaps your religion and your culture. But it's about getting together and doing projects to make the world a better place. So my suggestion to you, do something that you care passionately about and think about what you can do.

Greg Dalton: The last question upstairs.

Female Participant: Do you have hope in the future?

Jane Goodall: I definitely have hope in the future for five reasons. One is because of all the young people. So everywhere I go around the world I meet groups of young people who want to come and tell Dr. Jane what they’ve been doing to make this a better world, to help animals, people and the environment. It's not that young people can make difference, they are, all over the world all the time and they’re so enthusiastic and so inspiring. So that's one reason for hope.

Second is this amazing brain and, you know, we’ve invented so much technology to allow us to live in greater harmony with the natural world, clean, green, energy and things like that. And also thinking with our brains about what we can do each day to make a difference, to make the world better.

My third reason for hope is the resilience of nature. Like I said, all around Gombe the trees have come back, animal species on the brink of extinction are being given another chance. And then social media which, you know, it can be used for bad reasons but nevertheless, we can bring for the first time people together from all around the world. We may never meet them, we don't know them, but if they care about climate change you can have marches of people who passionately care and want to do something about it. And one of the climate change marches that I was part of was said to bring together more people around a single issue in the history of the world and that's because it was in something like 69 countries, I think.

And finally, the indomitable human spirit, the people who tackle the impossible and won’t give up and inspire others, the people with terrible disabilities who are out there inspiring others. And I just spent two hours with a young man from China who was born with no legs and arms to here, he is one of the most amazing, filled with life, filled with the joy of living that you'll ever meet, and he says I've been put together like this for a reason. And he goes around the world on a skateboard. He drives a tractor. This is an amazing man and I meet other people like that.

So yes, I have hope for the future because each one of us, every single one of us has that same indomitable spirit. We have to let it grow and get together and realize that in togetherness is strength.

Greg Dalton: That is -- it’s been a real honor to be here with Dr. Goodall and Jeff Horowitz the leading producer of climate change at work on the media. So let's give -- thank you for joining us and thank you Dr. Goodall.

[Applause]

Jane Goodall: Thank you.

Greg Dalton: Good night.

[End]