Dr. Robert Bullard: The Father of Environmental Justice

Guests

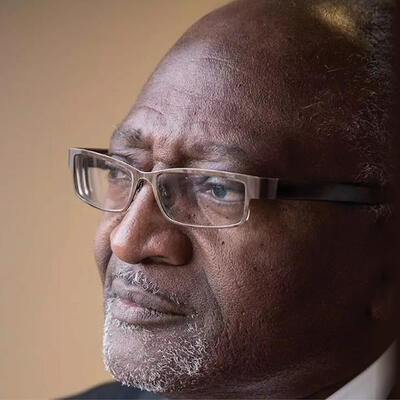

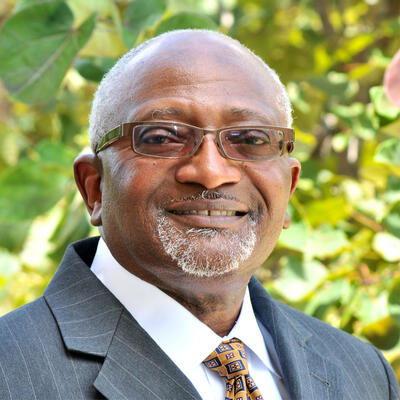

Robert Bullard

Adrianna Quintero

Summary

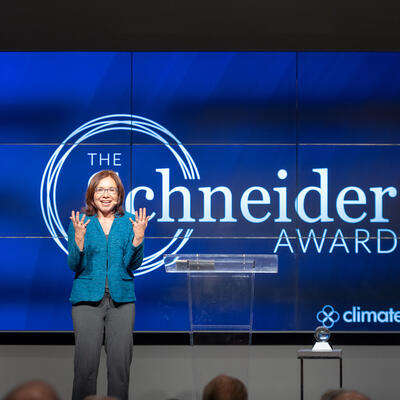

Climate One honors Robert Bullard with the ninth annual Stephen Schneider Award for Outstanding Climate Science Communications. Often described as the father of environmental justice, Bullard has written several seminal books on the subject and is known for his work highlighting pollution on minority communities and speaking up against environmental racism in the 1970-1980s. Bullard spoke with Greg Dalton at a recent Climate One live event.

“When you don’t protect the least in your society you place everybody at risk,” Bullard told the audience. “Justice will say, let’s do fairness, equity and justice to make sure that we do not somehow say just because you live in a low-income neighborhood that you don’t deserve to have a park, a grocery store and flood protection.”

Dr. Robert Bullard’s relationship with the environment began as a child growing up in the south, hunting and fishing with his father. He grew up in rural Alabama, not far from Montgomery – one of the centers of the civil rights movement. His commitment to social justice was strengthened by the activism of the 1960’s. He says that today’s climate youth movement reminds him of those days.

“We were fearless, we weren't afraid of going to jail,” remembers Bullard. “We weren’t afraid of basically people saying, well, you gonna get a C. Well, you know, having a C and can’t breathe - what's the purpose?”

“Every social movement that has been successful in this country has had a strong youth and student component,” Bullard states emphatically. “The environment justice movement, the civil rights movement, peace and justice, women's movement and right now the climate movement. You look at young people …they are owning these issues and they’re saying no, we don’t have to wait until we can vote to be mindful of the fact that we are destroying this earth and we are on the wrong direction, and we have to do something about climate crisis”

Established in honor of Stephen H. Schneider, one of the founding fathers of climatology, the $15,000 Schneider Award recognizes a natural or social scientist who has made extraordinary scientific contributions and communicated that knowledge to a broad public in a clear, compelling fashion.

This program was recorded in front of a live audience at The Commonwealth Club of California in San Francisco on December 12, 2019.

Related Links:

Dr. Robert Bullard: Father of Environmental Justice

Energy Foundation

This program was recorded in front of a live audience at The Commonwealth Club of California in San Francisco on December 12, 2019.

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One, changing the conversation about energy, the economy, and the environment.

On today’s program, we honor a sociologist recognized as the father of environmental justice.

Robert Bullard: When you don’t protect the least in your society you place everybody at risk. Justice will say, let’s do fairness, equity and justice to make sure that we do not somehow say just because you live in a low-income neighborhood that you don’t deserve to have a park, a grocery store and flood protection.

Greg Dalton: Dr. Robert Bullard’s relationship with the environment began as a child growing up in the south, hunting and fishing with his father. His commitment to social justice was strengthened by the activism of the 1960’s.

Robert Bullard: We were fearless, we weren't afraid of going to jail. We weren’t afraid of basically people saying, well, you gonna get a C. Well, you know, having a C and can’t breathe, what's the purpose?

Greg Dalton: Dr. Robert Bullard - this year’s recipient of the Stephen H. Schneider Award for Outstanding Climate Communication. Up next on Climate One.

---

Greg Dalton: Is a clean and healthy environment a civil right?

Climate One conversations feature oil companies and environmentalists, Republicans and Democrats, the exciting and the scary aspects of the climate challenge. I’m Greg Dalton.

On today’s program - social justice meets climate justice.

Robert Bullard: When we talk about communities that are on the front line we talk about the most impact and we talk about the economic consequences and we talk about the health effects. We talk about the whole idea of communities that will somehow culturally disappear.

Greg Dalton: Dr. Robert Bullard is Distinguished Professor of Urban Planning and Environmental Policy, Texas Southern University. He’s the author of eighteen books that address issues such as environmental racism, climate justice, disasters, regional equity and more. The Sierra Club named an environmental justice award after him in 2014, and he was named one of the world’s 100 most influential people in climate policy by Apolitical.

This year, Climate One is awarding Dr. Bullard with The Stephen Schneider Award for Outstanding Climate Communication. The late Dr. Schneider was a brash and brilliant scientist and communicator and an early advisor to me when I founded Climate One in 2007. After he died in 2010, I created the award, now $15,000, to honor scientists who are strong communicators.

Robert Bullard grew up in rural Alabama, not far from Montgomery - a center of the civil rights movement.

PROGRAM PART 1

Robert Bullard: Well, you know I grew up in an era where everything was segregated in the south. And, you know, I went to an all-black elementary school, middle school, high school. I never had a white teacher until I went to Iowa State University, worked on a PhD. My undergraduate university was all black, Alabama A&M University. So I grew up in an area where civil rights and fighting for justice was the same in voting and young people and students. I was part of that, you know, that student movement and so my parents and grandparents, you know, they were strong supporters of voting. Now I didn’t see myself, you know, growing up as an environmentalist, but in terms of growing up where having gardens and having this whole idea of not wasting things and being creative with the little that you have. I didn’t grew up impoverished or anything, you know, we had a little money because my great-grandparents actually was able to get 550 acres of timberland and ten years after slavery we don't know how they got it, but we know they got it. And that’s how my parents were able to sell the timber every six or seven years to send all my siblings to college. And so I was very aware of the environment in terms of outdoors and trees and nature. But it was not I guess rooted in this whole idea of modern environmentalism.

The idea of being outdoors and having rivers that were clean and pristine because my parents, my dad mostly fished, he was not an angler. It wasn't catch and release it was catch and bring home, clean and eat. And so that idea was all instilled and so it was not as I said the whole idea of being of how environmentalism was defined. We’re not members of organizations that had environment in the name but we were concerned about the environment we worked on environmental issues in a way that went unnoticed.

It was not until, you know, first Earth Day for example in 1970, April, I was in Marine Corps and there was a war going on, it’s called Vietnam. And so I was not you know, at the first Earth Day but it did not mean that I was not, you know, concerned about environmental issues. There were other issues that were like civil rights and voting etc. that had high priority but breathing also had a good priority also.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: More immediate and personal. I learned in your book that Dr. King was called to Memphis in 1968 and we all know that but I bet a lot of people don't know why Dr. King was in Memphis in 1968. Tell us.

Robert Bullard: Dr. King was called to Memphis in support of striking sanitation workers. And if you don't think garbage is an environmental issue that the garbage workers go on strike. And as a matter of fact in ‘68 they had to call out the National Guard to pick up the garbage and Dr. King was assassinated in April before he could finish his job. And of course I was in April 1968, I was a senior in college and of course devastated. That’s a long time ago but you think about it that’s not that long ago. We think about this whole idea of civil rights and environmental rights. And for the last, you know, 25, 30, 40 years to get civil rights and environmental rights to converge it took a lot of work and convincing our environmental brothers and sisters organizations, but also it took a lot of convincing of folks on civil rights to work on these issues with the same fervor that they brought to civil rights and human rights. And it finally occurred with the convergence into what we call environmental justice.

Greg Dalton: And in the late 1970s, 1979, a seminal moment in that conversion, Congress banned PCBs in 1979 and there was effort to find a dump basically for these toxic carcinogenic chemicals and a spot was identified in Warren County, North Carolina, a new landfill. And that in some ways there's sort of the creation story of environmental justice. So tell us what happened there and you worked with Benjamin Chavis who played a key role in that.

Robert Bullard: Well, Dr. Chavis led the struggle in Warren County in 1978 when it’s coming from New York came down to Raleigh and wanted to recycle this oil. And they find out that the oil that they were gonna recycle had been contaminated with PCBs. And since they couldn’t recycle it because of the law they dumped it along the highways and they cleaned it up. Then they needed a place to put this contaminated dirt. And so they went through this rigorous process of selecting the most scientifically suitable place. And of course there was no science the only science in law was political science. And when they opened the envelope the winner was Warren County. One of the poorest and one of the blackest counties in the state. And Dr. Chavis and the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice and NAACP and the communities in Warren County said no. And Dr. Chavis coined the term environmental racism this is environmental racism.

And almost 500 people were arrested, you know, 1983 it was a pivotal year in that, you know, Dr. Chavis and the commission the general accounting office to do a study on what was happening in the South. They found out 75% of the hazardous waste facilities in the South located in black communities, even though blacks only made up 20% of population. And so the idea of this national movement gaining steam out of Warren County and that they were isolated, struggles going on all across the country even the one in Houston and other places across the country. But Warren County put the issue on the map and people put their bodies in streets. High school kids laying prone trying to stop these dump trucks and people are arrested and the continuous sustained struggle. People saying, no, no, no and this is when the environmental justice movement came together and people started to identify with that struggle. And so that was a shot heard around the world, Warren County.

Greg Dalton: And as the United Church of Christ played a -- what’s the racial complexion of the United Church of Christ?

Robert Bullard: Well the United Church of Christ is a white denomination, but the commission for racial justice was a black civil rights organization based in the church, faith-based group in the church. And the whole concept of merging civil rights and environmental rights and the faith community that was something that emerged out of the civil rights movement. Struggle against injustice whether it was housing, voting, education it now had basically been pushed into the right to live in a clean, healthy environment where were you don't get dumped on just because of the color of your skin or the amount of money you make.

That was novel and you would think it would be commonplace, you know, since everybody breathes the air and drinks water and eat food you would think that that would be something that was real and not aspirational. We don’t decide on Tuesday we’re not gonna breathe, so it’s like this is something that should be basic.

Greg Dalton: And it took the church and moral leadership to help kind of fuse that, put that in a moral frame.

Robert Bullard: Yes, it did. And the idea that young people, got out of school and cut classes, this is 1983, ’82 and basically said no --

Greg Dalton: The height of Reaganism.

Robert Bullard: Yes. Yes. And so when you talk about this whole idea of social movements and the role that young people and students have played. Every social movement that has been successful in this country has had a strong youth and student component. Back in Warren County with that birth of the environment justice movement the civil rights movement, peace and justice, women's movement and right now the climate movement. You look at young people and what they’re doing what they’re saying. They are owning these issues and they’re saying no, we don’t have to wait until we can vote to be mindful of the fact that we are destroying this earth and we are on the wrong direction and we have to do something about climate crisis.

It reminds me of us in the 60s. We were fearless we weren't afraid of going to jail. We weren’t afraid of basically people saying, well, you gonna get a C. Well, you know, having a C and can’t breathe what's the purpose. And so the idea that there's a calling that you have to say, no we have to change. And those with the most energy who can you think of other than young people they have lots of energy. And so we have this intergenerational movement struggle for justice and I’m biased, you know, I am for justice.

Greg Dalton: Environmentalism is often been a bipartisan issue in this country. Certainly President Nixon would be a radical environmentalist by today’s standards. The first President Bush, I learned from you, was surprised actually created the first office of environmental equity in the EPA. Tell us about that creation and why?

Robert Bullard: Well, you know, the creation of that office was the impetus that followed a conference that was organized by Paul Mohai and Bunyan Bryant at the University Michigan where they basically pull together a few of us few academics and you could almost fit them on one hand that we’re working on, this is 1991, working on environmental justice. And they had a conference at the University of Michigan raising the incidence of environmental hazards. And a few governmental people, EPA was there and some community people. The conference was such a great conference they said we need to write the EPA and the persons counseling on environmental quality and Health and Human Services and ask for an audience with them and we got an audience with EPA, William Reilly and we had a sitdown. William Reilly was an environmentalist, a conservationist, he came and director of EPA, a Republican. So after we met with him he made a commitment.

We’d have conference calls every quarter every three -- is a quarter three months? Okay. And so he made a commitment to us that he would make some changes inside of the EPA and he created the office of environmental equity. Now, we wanted the office of environmental justice we said we’re not asking for equity. Equity means in some people's mind meant that we were talking about spreading the poison equally. Now we said no, that’s not equity that’s madness. We said we want justice, no community to be poisoned. So he created this office and then he produced the first national report on environmental justice. The report was entitled environmental equity reducing risk for all community. Still they were afraid of justice for some reason but equity was a softer term. We say you can call that title anything you want but we know what we want from our justice communities around the country. And then they had a definition they defined environmental justice and then they defined just treatment. You know the government has to define anything before they can do anything.

Greg Dalton: You’re receiving the Stephen Schneider Award for climate communication, Stephen Schneider was a fearless communicator and he was in the natural sciences but he had a unique I think understanding he talk to economists and social scientists across the disciplinary communication which was fairly rare in the climate world back then. So I’d like to hear your thoughts on the importance of kind of communicating the science and sociology and kind of the different disciplines speaking about climate which is seen kind of as an atmospheric far away issue; at least it has been.

Robert Bullard: I think the idea of climate change and this whole issue of the science and how we communicate that science. And to expand what it means when we talk about climate crisis or global warming or climate change that climate change has to be defined more than parts per million and more than greenhouse gases. When we talk about communities that are on the front line we talk about the most impact and we talk about the economic consequences and we talk about the health effects. We talk about the whole idea of communities that will somehow culturally disappear. And when we define and communicate that outward then we have more people that will come to the table and say, oh I understand what you’re talking about. I am you know, we don’t ask people to believe; it's not a belief. It’s like asking people do you believe in gravity, jump off a 12-story building. So when we talk about communicating the issues I think we have to be multilingual when it comes to different disciplines. You know I’ve written 18 books on transportation, housing, you know, on food security on disasters and they got catchy titles. But it's just as, it’s 18 books but it’s just one book don’t tell anybody. The thing that hold those books together is fairness, justice and equity.

And when you look at climate and look at the fairness justice and equity with the science part you can see how the justice part that's the policy. And that's how we ought to start addressing this because, you know, we could have deal with climate change in one little corner of the earth and not deal with all these other equitable or inequity and still not address the total picture locally as well as globally. And so what I’m trying to do is when we talk about climate change and we talk about these other issues how we bring in economics. We bring in transportation, energy. You know, I wrote a book called Just Transportation, yeah, Just Transportation. Get it? But the idea is -- and I wrote another book called that dealt with transportation called Highway Robbery. So if you look at, you know, both of those deal with energy, mobility, they deal with issues of infrastructure. And so when you start defining and bringing in the climate piece you’re talking about energy you’re talking about transportation you’re talking about infrastructure, you’re talking about jobs, you’re talking about access to opportunity, all those things. And we used to get all, oh you’re talking about social issues we deal with the environment.

You have to do what you have to do and you have to bring organizations bring the idea of justice, fairness and equity even some of the smartest people along. Because sometimes people are only thinking in their own way of thinking. And so in communicating out you try to bring those people in I guess a way that they can see how things work. And the word for the day is intersectionality. Intersectionality. How things connect and how you can make sure that people understand those connections. It’s like connecting the dots. It’s like kids’ work. You know, as a kid you used to connect the dots that's what we’re doing.

---

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation with Dr. Robert Bullard. When we come back - how post-Harvey recovery efforts brought the fight for equality to Houston’s poorest neighborhoods.

Robert Bullard: It took a biblical flood to get environmental groups...to come together with groups of the environmental justice, groups of faith-based groups, groups working on transportation and food security, etc. to come together. And we say it should not take a disaster for us to come together.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

---

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton, and we’re talking about the intersection between civil rights and climate equality. My guest is Dr. Robert Bullard, Professor of Urban Planning and Environmental Policy at Texas Southern University and widely recognized as a founder of the growing field of environmental justice.

Joining us now is Adrianna Quintero, director of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at the Energy Foundation. She began her involvement in the environmental justice as a litigator for the Natural Resources Defense Council. But she soon realized there was a disconnect between the organization and the community they were representing.

PROGRAM PART 2

Adrianna Quintero: We were working on pesticides litigation. And so it was very obvious to me that there should be some Latino farmworkers represented in these cases. And while they were referenced and we were talking about them we weren't talking to them. There was not that connection at least and we were doing the litigation. So for me that was a clear disconnect and something that needed to be addressed. Fortunately, I was working with a really amazing lawyer who is very committed to environmental justice to this day. And he just basically said, you're right, let’s go do it. Let’s go and start figuring this out.

And that began my journey to try and to really learn I had to educate myself. I did not come to this work knowing all the history and this wonderful work that people like Dr. Bullard had done and the environmental justice movement had done. So for me, it was really a learning journey to see and try and make sense of the disconnect which to this day I have trouble understanding how we got there how we got here, how we got to the point where the environmental movement really lost touch with the humanity and the communities that were most impacted. It just continues to motivate me every day.

Greg Dalton: Dr. Bullard I’m a big believer that business models drive a lot of organizational behavior and a lot of the environmental groups rely on upper income coastal elites to write checks to fund their organization. In 1991, you were part of a group of people who wrote to the Big Ten environmental groups and said you're not -- I think you even wrote an article saying can Houston be green if it's not brown or black did I got that right? So, tell us about you know are environmental groups you said the Sierra Club wouldn't allow black people are they afraid of race because of their funders?

Robert Bullard: Well, you know, I don’t want to go into anybody’s head. I’m a sociologist not a psychologist. But I do know that if a green organization does not look at the change in demographics of this country and start to I wouldn’t say color coordinate, but at least color coordinate and diversify then they’re gonna find themselves losing memberships or whatever.

What we have found over the years is that when we organize the first National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in 1991 under the auspices of the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice and Dr. Chavis, we basically said that people of color must be in a room must and communities on the frontline must have a voice at the table. And when we had those 4-day summits we said that we will developed out of this summit organizing principles. And when people went back home many of them organized grassroots organizations and started networks, etc.

And what we says is that we will press and pressure the green groups to become more diverse in terms of their boards and their staffs and agendas. But that would not be the driver at the forefront of our movement. Our movement is to make sure that those communities of color that are faced with many challenges when it comes to environment need to have their organization their institutions funded at the level that's commensurate with the problem. Because if we somehow keep funding the same groups and we keep, you know, add one or two persons to the board what I call the “whom” syndrome, we have one minority. If we start using that principle the money will still flow and you’ll have a whom on a board and that still won't solve the problem of organizations of color that are underfunded. We can do both. We can walk and chew gum at the same time. We must diversify the organization but we also must diversify the funding. Can I get a hand?

[Applause]

Greg Dalton: So Adrianna Quintero, you work for an organization that funds about $100 million, which is relatively small in the big world of philanthropy. But there have been studies done that show that the lion’s share of philanthropy goes to the big national organization which are predominantly white. Have philanthropists done a good job to responding to Dr. Bullard’s call?

Adrianna Quintero: No. And I would go ahead and also and add to the answer that Dr. Bullard put so well. I think there has been a discomfort with talking about race. There has been a discomfort with facing looking in the mirror and realizing that big changes need to be made. And when things appear, appear and I really emphasize “appear” to be working, it’s even harder. But working for who, right or whom, right. But no really, how are they truly working. And I think it’s taken far too long, at least as long as I've been in the movement to come to that realization that now we're seeing philanthropists realized we really missed the boat on this. We’re so far beyond time to really get close and just take the spotlight off of the white groups and look at the communities that are facing these problems every single day. Because where is the knowledge more rich than there. And I think this overreliance on science and data really dulled us I think for a long time and drew us away from the stories which is really what motivates people and motivates change. And I think that's why to your point earlier why we’re seeing so much movement is because that energy is driven by the story. And so I'm heartened to start to see the change now but we didn't have to wait this long.

Greg Dalton: Dr. Ibram X. Kendi is the founding director of the Antiracist Research and Policy Center at American University. His latest book is called How To Be an Antiracist. At the Commonwealth Club recently, Kendi was asked how we can talk about racism and antiracism in a way that helps people understand where they fall.

[Start Playback]

[00:39:33] Ibram X. Kendi: It's not who a person is. It is what a person is doing in that moment and people change. And so people when we were talking about healthcare they can speak from an antiracist perspective then when we talk about criminal justice they think that black people are dangerous. But then when we talk about education they believe that inequities stem from resource inequities. But then when we start talking about climate change they’re like what climate change, right. That is not affecting the global South more than the global North, right. And so ultimately people are distinct when it comes to different issues, but then also even on the same issues, even in the same speech even in the same paragraph of the same speech, people can say both racist and antiracist things.

[End Playback]

Greg Dalton: That was Ibram X. Kendi, professor and author of the recent book How To Be an Antiracist. So Dr. Bullard, your response there that people can kind of move in and out of that place based on the issues they're addressing.

Robert Bullard: Yes, exactly. And I think when we talk about race it’s very difficult for some people to talk about race they shut down. And so just like the concept of justice. Justice, when we’re talking about justice at EPA, you know, back in ‘91 they saw that as threatening. And so in some cases when you say, well no we want justice. Justice means going back looking at some of the things that -- distributive kinds of challenges and policies that have legacy issues that go back.

And so when we talk about race and racism and when the environmental justice groups wrote that letter to the Big Ten back in ‘91, not the football Big Ten, the green groups they were called Big Ten, for all you youngsters out there, way back when. A lot of the groups got offended. How dare, they said, well look at your boards, all white is it? Yeah. They said, look at your staff, all white. Yeah. Look at your agendas. Yeah. So we’re not calling you racist we’re just saying what you're doing is not working on our behalf.

Then some of them said, well, because all the green groups are not, it’s not broad brush they’re different just like the environmental justice groups different. They said, well, you know, we’re gonna make some changes we’re gonna go forward. And some of them did. Some of them say, how dare you call us racist we don’t want any part of you. And so you see some of that and so you can look at that trajectory of who has been out front moving things and trying to address things and trying to reach out and trying to, you know, bring in partners and coalitions and alliances and etc. and who is not.

And I'm not gonna call any names but I could but I don't have to. If you’re engaged with some of these organizations some of these groups we had to fight our oldest civil rights organization, not calling name but you know the initials. We have to fight them because they said we don’t work on environmental issues. And we say are you concerned about black people breathing? And then it took 20 years for our mainstream civil rights organization to get on board with these issues of environmental justice because they're saying oh you’re trying to shut down jobs. We say no. We want people to have good jobs safe in terms of the workplace and fenceline communities. We want the fenceline communities to be safe as well as the workers. When we start explaining to them what we're talking about they said, oh we get it.

So unpacking that kind of injustice and when it’s racism call it for what it is don’t run from it. And like I said, all injustice is not racism. It took us almost 10 years for the people in Appalachia or Appalachia whichever you want to call it, to understand that we were not calling all environment injustice racism. And lot of the whites in Appalachia were somewhat hesitant about working with us because they were thinking that we were talking about racism all the time. We said no. Mountaintop removal, contaminating your water, contaminating your air making people sick. We will fight just as hard for you to get and keep clean air, clean water and safety in your neighborhoods, etc. as we would in Mississippi or in Louisiana or Texas. See this whole idea that some way people can’t fathom the fact that black people and people of color and indigenous people are out front ahead of a lot of the very smart organizations who have PhDs at their heads and engineers and environmental scientists at their head when it took them 20 years to understand what we are talking about. And we were writing and speaking in English.

---

Greg Dalton: If you’re just joining us, Dr. Robert Bullard is distinguished professor of urban planning and environmental policy at Texas Southern University. And Adrianna Quintero is director of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion with the Energy Foundation. I'm Greg Dalton.

Adrianna Quintero, the Green New Deal is this aspirational thing that's out there that a lot of people probably couldn't quite define but it’s stirred quite a debate. And I think that the inclusion of some of the justice and economic issues that Dr. Bullard is talking about scare some liberals makes them uncomfortable because they think they're going to lose some of their privilege some of their wealth, is that fair?

Adrianna Quintero: I think that’s fair, I think that’s why it stirred so much debate. But to quote again what Dr. Bullard said earlier. The Green New Deal came on the scene with a big bang because of the intersectionality that it presented. And it really brought to light the reality that we can no longer think of the environment as one bucket that just sits alone in this silo. No, it has to do with transportation, it has to do with housing, it has to do with jobs it has to do with health. All of these things are tied directly to our environment to where we live to our opportunities. And there is absolutely no threat to thinking of it that way. That’s actually how we break this logjam that we've had and frankly take the energy out of the others who debate whether or not environmentalism is something that's important.

When we start to show the connection to every single part of our lives it’s undeniable. So anyone who is nervous about this particular piece of legislation just needs to look at how it’s energized the conversation. It has sparked debate like no other piece of policy has at least and again in my lifetime in this movement and I think that is where we need to be. We need to start talking about solutions that actually benefit everybody and benefit all the aspects of our lives. Because if we continue to silo environment, we’re gonna lose a lot of people and it’s just not realistic. And the people who are gonna be most impacted are communities of color which we were just talking about the insanity behind excluding communities.

When you look at the polling behind communities of color, every single time we've looked at it the support that exists for climate policies the awareness of the fact that climate change is happening is so much higher among communities of color. And when you’re looking at Latinos when you’re talking about Spanish-speaking only communities then it’s even higher. And so why wouldn’t we take advantage of the fact that even if you wanted to just be brass tacks database that's a ton of people. And it’s the same thing when you look at the people who are energized by the Green New Deal there’s millions of people who would have never stepped into the space had that not come on the scene. So that energy to me is what we need much more of and we need to continue to generate that and have that these new and innovative ideas. They might seem scary to some but it’s just because change is, you know, makes us a little nervous. And you know what, that’s a good thing that means we’re growing.

Greg Dalton: Dr. Bullard a lot of the quote mainstream environmental efforts have been funded by people who basically want to keep the economic and class structure in place and they're worried that their house in the woods might burn down or their house on the ocean might get flooded. And they want to keep things the same and kind of swap out fossils for clean but they don't want to tackle some of these deeper racial and structural issues is that fair?

Robert Bullard: Yes. The long and short of it is that I think the time has passed for tinkering around the edges. The fact that we are facing a threat in terms of climate change and global warming that it will call for bold action and bold decisions that will need to be made across the board. And economic political in terms of our transportation systems and in terms of our energy systems in terms of our housing, in terms of land use planning and in terms of all those things coming together. So it’s not just we talk about solution you just can’t have a few policymakers sitting in a room who’ve all been trained in one little area who went to the same school who may not understand anything that’s going on the ground in a community. They’ve flown over it 30,000 feet and at 30,000 feet everything look small. Looks great. You can't see the granular kind of thing.

So we need to really think through this whole idea of keeping things as they are. Right now in Houston, Texas, fourth-largest city in the country, only major city that doesn’t have zoning were fighting like hell to make sure that the recovery does not post-Harvey recovery does not reproduce the pre-Harvey inequality. We don't want to rebuild on inequality and make it like it was because like a was it’s unequal. It took a biblical flood to get environmental groups mostly white groups in Houston to come together with groups of the environmental justice groups of faith-based groups, groups working on transportation and food security, etc. to come together.

And we say it should not take a disaster for us to come together.

But 2018 election was a blue wave in Houston and the old guard was swept out, new guards came in and the idea of building equity into way funding building equity into the way that decisions are being made, having the right people who have been exposed to inequality for decades in charge they can see that it makes a whole lot of sense to build out housing because housing affordability is a big issue, transportation a big issue, access to jobs on the issue around flooding, around issues around land-use plan and etc., all these things have to be dealt with and not just one issue of flood mitigation. So if they go with the old guard they just want to do flood mitigation and money follows money, money follows power, money follows like that’s how it’s done before. That’s the formula that’s shown and it comes out in study after study. With the cost-benefit analysis you get money following where the most damage the biggest homes cost-benefit analysis will say, well you put the money over the $800,000 homes are why should you invest in 80,000 dollar houses when it cost 40,000 to do whatever. They’ll put the money over where the big homes are and the big homes and neighborhoods with the big homes will see their property values increase whereas the communities of color will lose. They will lose out, study after study.

And so when we say let’s not keep that policy in place that will push that will marginalize communities further down the economic ladder and at the same time move more affluent at another level which they increase their home values and their quality of life their disaster preparedness and their resilience, etc., where just you make poor communities even more marginalized.

Now that’s what we're fighting in Houston, we saw that, you know, play out in New Orleans after Katrina. We’re seeing it play out in disaster after disaster. And we said, that should not be. When you don’t protect the least in your society you place everybody at risk. And so our thing is justice will say, let’s do fairness, equity and justice to make sure that we do not somehow say just because you live in a low-income neighborhood that you don’t deserve to have a park, a grocery store and flood mitigation and flood protection, you don’t deserve access to transportation.

We say that’s the equity part that’s the justice part. Let’s deal with the whole picture and not just somehow just because your neighborhood flooded for the first time, now you just want to deal with one issue. The justice framing and the equity lands will say we need to address those legacy issues that somehow got swept under the rug or got somehow wiped off of the slate of policy. And that's what we're fighting for right now. And for someone who has tenure, I'm not shy, I’m not timid. And at my age I don’t care what people say.

---

Greg Dalton: You're listening to a conversation about the fight for environmental equity. This is Climate One. Coming up -- are we solving our social justice problems, or just passing them on?

Audience Member: Because often when you fight a refinery or a dump out of your community it’s moved to another community or exported to a different country where there’s less regulation and it's less expensive to dispose of.

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

---

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. We’re talking about environmental and social justice, with Dr. Robert Bullard of Texas Southern University, and Adrianna Quintero of the Energy Foundation. Dr. Bullard is this year’s recipient of the Stephen Schneider Award for Outstanding Climate Communication, presented by Climate One.

Let’s go to questions from our live audience.

---

Female Participant: Hi. My name is Summer-Solstice Thomas. I’m an environmental studies major at Williams College. How do we, when looking at like chemical and municipal waste disposal and even like chemical production, how do we pursue justice? Because often when you fight a refinery or a dump out of your community it’s moved to another community or exported to a different country where there’s less regulation and it's less expensive to dispose of. So how do we find like true justice and not just equity like you’re talking about just spreading the pollutants for everyone.

Robert Bullard: Well, it’s not easy and it’s not complex. You know, the idea if a community or a city produces the waste, it should figure out how to deal with it and not export it. In Houston since that lawsuit was filed in 1979, Bean versus Southwestern Waste Management Corporation. Not a single sanitary landfill has been located in Houston since that lawsuit. And what that lawsuit did it forced a city that doesn't have zoning, it forced white people to say, we’ve run out of black communities to put landfill because we’re gonna have bunch of lawsuits. We must figure out a way to deal with our waste because we know landfills are not compatible with white communities.

And so they went to a very aggressive waste minimization composting program. And so the idea of reducing the amount of waste and extending the life of landfills and coming up with alternatives, etc. and recycling. This is the city that prided itself as unrestrained capitalism, meaning that laissez-faire you could do anything you want, now has forced itself to come with ordinances and regulations that was forced upon them because of lawsuits. I don't think we need to be exporting waste and cross boundary waste trading.

And again when we work on landfills and waste management issues we don’t say, oh send it over there. We work with communities, the over there communities, and make them aware of what the issues are. And so we’ve been able to slow down a lot of the -- sending it across the border and exporting the problem somewhere else here in the U.S. as well as abroad. And the fact that, you know, with the spat with China in terms of the trade spat with China, you know, a lot of the “recyclables and waste” now is piling up here because China is saying no. That means it’s forcing us to do something.

Greg Dalton: Next question. Welcome.

Male Participant: Hi my name is Carter Brooks. You mentioned your whom thing a lot of well-meaning groups, communities, etc. of white people wanted to be more diverse are often trying to just bring people to them rather than learning to go out to those communities and find out what they need. So I'd like either of the guests to speak up about what more or how we can promote a different way of thinking. So that's the first thing we start thinking of about how we’re gonna go to those communities to find out what they need rather than pretend we need them in any way. Any way you want to speak to that issue.

Greg Dalton: Adrianna Quintero, lot of times it’s those predominantly white organizations going to communities of color saying, we know what your problem is and here’s how you should solve it.

Adrianna Quintero: Yeah. I mean that’s exactly what we’re trying to change. And what I see happening now, which I think is why the tide is really starting to turn is we’re starting with race. We’re having that conversation about race. If we don't start there it becomes really easy to make a lot of assumptions and just kind of pat ourselves on the back. But when you start with race you have to face your bias you have to face those assumptions and you have to realize that especially if you’re a white organization, predominantly white, that you don't have the answers, that you can't even begin to have the answers. So it really changes your stance from one that is paternalistic and all-knowing to a learning stance. And that's really hard for people and it is absolutely essential. If you don't have that as your first step, I don't know how you really get to that openness. We have to develop a growth mindset around this and we have not had that. So it's essential that we face our bias and talk about it and name racism and classism and privilege and all of these difficult conversations if we’re really going to have a meaningful conversation and make change.

Greg Dalton: Let's go to our next question. Welcome.

Male Participant: Sure. Hi, my name is Kay. It’s pretty much the same question just more specific. Climate One’s audience is really white and same with the Commonwealth Club. How does this organization bring more diversity here?

Greg Dalton: Great question. You know it’s certainly an establishment organization having programs like this. These all sorts of issues of getting people I think sometimes the Commonwealth Club name feels like, that's downtown will I be comfortable there? Is that like all white men with leather wingtip chair? People have a certain perception, right, of that name. And it used to be that 75 years ago but now, you know, it's something I think we struggle with just as much as other organizations. Having programs like this and certainly spreading the word, if you'd like to talk afterwards and you have some suggestions, I’d love to hear them. Because we kind of reflect the -- we do a lot to have gender balance we’re pretty proud of the gender balance we have in our program. It’s about 55/45, it's less balanced racially and ethnically. So thanks for that question. Welcome.

Male Participant: Good evening everyone. My name is Alexis Cureton and I’m a clean energy and equity advocate here in San Francisco. And the question that I have for you is in the face of utility power shut offs and the impending earthquake that everybody keeps talking about again I’m from Indiana so all of this is new to me. How do you suggest communities of color really frame the discussion around resiliency when understanding like you were saying we are not really at the head of these organizations a lot of us come in as assistants or program managers and so on and so forth. A lot of this is new to us. So how can we really help frame the discussion and not only frame it but really lead these movements within these institutions.

Robert Bullard: Well, you know, I'll give my biased opinion. I think the equity lens has to be applied across the board where we talk about the resilience concept but also in terms of who's at the table who's leading these issues. The equity starts at home and that has to be something that's gonna drive this whole process. Making sure that you have a diverse pool of folks who are making decisions around how we’re gonna drive this resilience train. And it can't be just the same people all the time. Moving from one issue to the next issue where we talk about sustainability and then we talk about resilience. And then we’re talking about, you know, the climate over here and here we’re talking about, you know, this issue over here. It has to come together.

And that cross-fertilization that intersectionality for me will be key. And even though the resilience might be new to you on one area there are other areas where you have lots of expertise and you can bring that expertise into that room that’s talking about resilience. Because you can’t have a resilient city if that city somehow keeps building on the inequality and somehow economic inequality racial inequality the spatial inequality. Those things have to be brought into the mix and sociologists are very good at that.

---

Greg Dalton: You’ve been listening to Climate One. We’ve been talking about climate change and environmental justice, with Dr. Robert Bullard, Distinguished Professor of Urban Planning and Environmental Policy at Texas Southern University, and Adrianna Quintero, Director of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at the Energy Foundation.

Greg Dalton: To hear more Climate One conversations, subscribe to our podcast at climateone.org. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review wherever you get your podcasts.

Greg Dalton: Kelli Pennington directs our audience engagement. Tyler Reed is our producer. Sara-Katherine Coxon is the strategy and content manager. The audio engineers are Mark Kirchner, Justin Norton, and Arnav Gupta. Anny Celsi edited the program. Dr. Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.