Congregation Power

Guests

Rev. Sally Bingham

Yonatan Neril

Don Ng

Summary

“As a priest, if I’m going to start talking about what humans are doing to the planet...I need scientific backing. I need to be in close communication with the scientific community or I have no business making those remarks,” said Rev. Canon Sally Bingham. Leaders from many religious traditions are acting as stewards of creation by powering their congregations with clean energy and encouraging smart policies in their communities. Leaders of this movement contend that all major religions have a mandate to care for creation. “Being at the top of creation we have a particular responsibility to treat it with respect,” Rabbi Yonatan Neril says.

Religious leaders come together at Climate One to discuss how their faith impacts their approach to climate change and what they are doing about it. “Solar panels and solar energy is achievable,” Rev. Don Ng told us. Listen in to hear how communities of faith around the world are getting involved to build a more sustainable future.

Rabbi Yonatan Neril, Founder and Executive Director, Interfaith Center for Sustainable Development, Jerusalem

Reverend Sally Bingham, Founder, Interfaith Power and Light

Reverend Ng, First Chinese Baptist Church, San Francisco

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: Welcome to Climate One, a conversation about energy, economy and environment. To understand any of them, you have to understand them all. I'm Greg Dalton. Religious leaders of all faiths have expressed support for reducing carbon pollution that is heating the sky and hitting the Earth's most vulnerable people. Pope Benedict XVI, Rowan Williams, Archbishop of Canterbury, the Dalai Lama, Desmond Tutu, and many others have spoken about the moral imperative of protecting the Earth's beauty and bounty for future generations.

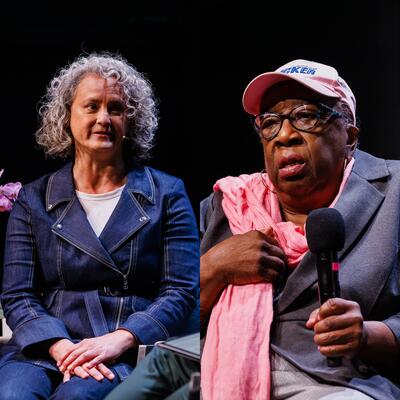

Faith-based communities are also taking action by putting solar panels on the roofs of churches and temples, insulating drafty houses of worship and activating their members. Over the next hour, we'll talk about Congregation Power with our audience here at the commonwealth club in San Francisco. We are joined by three religious leaders actively engaged in creation care. Reverend Sally Bingham is founder of Interfaith Power and Light, a national advocacy organization, and Rabbi Yonatan Neril, founder and executive director of the Interfaith Center for Sustainable Development in Jerusalem, and Reverend Donald Ng with the First Chinese Baptist Church here in San Francisco. Please welcome them to Climate One.

[Applause]

Greg Dalton: Well, faith is a lot about storytelling. I want to start with your individual stories and hear from you how you came to the intersection of faith and environmental stewardship, and then we'll talk about your organizations and other topics. But Reverend Bingham, let's begin with you. How did you come to this intersection of faith and environmental--

Sally Bingham: I'm not sure starting with me is a very good idea. It was a long process. I mean, it was --

Greg Dalton: Well, this is a -- yeah, not --

Sally Bingham: -- a lifetime experience.

Greg Dalton: So you're saying there's a 45-minute answer there? Is that what you're saying?

Sally Bingham: That's what I'm saying. But briefly, I have always been interested in what humans were doing to the planet. Whether it was deforestation or dying coral reefs or climate change or any number of the things that humans are doing that is destructive to nature. I've been an Episcopalian all of my life, but I never heard anyone talk about saving creation from the pulpit. And I've found this really lacking in our religion. We pray for our reverence for the Earth almost every Sunday, and to me, having a reverence for the Earth means you have a reverence for the Earth -- you treat nature as if it were sacred. And yet we were not doing that. We were not -- we were hypocrites in the sense that we -- we even denounce any evil that destroys creation in our Christian baptism of the house.

So, I started asking clergy, "Why, why do you never talk about saving creation? How can all these people sit in a pew on a Sunday morning, profess their love for God, be called to love their neighbors and be polluting their neighbor's air and poisoning the water and putting engine oil in the storm drain behind the house, where does it go, it goes to your neighbor --" and eventually, one of these clergy people who was tired in me asking the questions said, "Why don't you go to seminary and find out where the disconnect is between what you say you believe in and how we behave?" Well, I have never been to college so I couldn't go to seminary. So it was this long process.

I went to the University of San Francisco at 45 years old, entered as a freshman, got a wonderful Jesuit education, still interested in the environment. After four years of college, still I never heard a clergyperson talk about saving creation from the pulpit, so I went back to Bishop Swing and I said, "Would you sponsor me to go to seminary now that I have gone to college?" And yes, I was -- went over to Church Divinity School of the Pacific, went through three years of seminary. In the process, realized that perhaps this was a true call from God to be the one that gets into the pulpit and hammers "hellfire and damnation" away to people in the pews if they were not gonna be the good stewards of creation that we are called to be. One thing led to another and I was ordained in 1997. And now, this is my life work. It's what I dedicated my ministry to and what I do.

Greg Dalton: And we'll learn more about your organization shortly. Reverend Ng, tell us how you came to the intersection of faith and stewardship.

Donald Ng: Well, in a very similar way. A commitment of this kind takes time. It's a lifelong journey. Growing up in Boston, I knew that they would -- all these public science that says, "Do not litter," you know, you pack up your own debris or your trash when you're hiking -- well, here in San Francisco, as Sally mentioned, things that you drop or you leak onto the street would eventually pollute the Bay. And so for me, personal action is very important to my own commitment. And as I learned that what I do as an individual can affect others, and especially my neighbors and the larger community, then it becomes an issue of conscience.

That what I do will affect everyone else's livelihood as well as their health. As an American Baptist, you know, Baptists are always known to be evangelistic, that we concern about the salvation of the individual. But our denomination at the American Baptist also has a commitment on what we call eco-justice that you can't win just a person's soul without also caring for the justice that happens -- that needs to happen in our society as well as our natural world.

And so I grew up with that kind of background in my own childhood and during my youth years. And when I was called to be a minister, I saw that as part of my -- also prophetic voice.

Greg Dalton: And Rabbi Neril, you had some form of experiences at Camp Tawonga and Yosemite and others. So tell us how you came to faith and stewardship.

Yonatan Neril: So I grew up here in the Bay Area on an acre of land which I gardened with my mother. We had an organic garden and a big orchard of fruit trees. And every summer, I would go to Camp Tawonga, a Jewish summer camp near Yosemite where I was exposed for the first time to the connection between Jewish teachings and the environments, in this case, in one of the most beautiful places in the world.

I then studied a BA and MA program at Stanford with a focus on global environmental issues and during that time, did research in India and Mexico and Cuba on environmental issues. And I came to Israel about ten years ago and studied in a rabbinic program where I encountered Jewish text from these particular lands and realized that the Jewish tradition has very profound things to say about environmental sustainability.

And out of this experience, I founded the Interfaith Center for Sustainable Development which is based in Jerusalem and works to promote environmental sustainability based on faith teachings.

Greg Dalton: Let's talk a little bit about some of the scripture, then we'll get into sort of congregations and solar panels on the roof and that sort of thing. So if someone comes to you and says, well, you know, "where do you find in the Scriptures the origin or what's your favorite passage to cite in your respective teachings that sort of, that points to the obligation for stewardship?" Rabbi? What would you -- in the first testament or others, what would you point to?

Yonatan Neril: Well, I would point to -- when in Genesis, the first chapter of Genesis, "God blesses people to be fruitful and multiply and fill the Earth and dominate the fish of the sea and the birds and the animals." Ironically, according to Jewish tradition, that verse is actually a profound instruction for stewardship. The midrash, part of the Jewish oral tradition, teaches that we are only given dominion over creation if we act righteously. If we do not act righteously, then the opposite happens, the human beings are ruled by animals. And that these verses about our being -- sort of at the top of the hierarchy in creation, means that we have a particular responsibility to treat it with respect and to care for it.

Greg Dalton: Reverend Bingham?

Sally Bingham: Well, I think that all of that is correct and I often use dominion, not dominate. I mean, I always try to differentiate between dominate and dominion and I very often tell people that the dominion that we're given over the Earth is the same dominion that God has over us, which is to help us be the best we can be -- to care for.

And we have dominion over our children and we don't break our children's arms and ribs. We help them be the best they can be, and that's the dominion that God gave us. But the one that I use the most if someone said, "You can come up with one bit of Scripture to support an environmental effect." I use what I mentioned early on, the first commitment, which is to love God, and second, is like unto it which is to love your neighbor as yourself. Well, if you love your neighbor, you don't put engine oil in the storm drain behind your house. It goes to your neighbor. And then it goes to the bay and then to the fish and who eats the fish? We do and that points out interconnectedness of all things. But I use that -- I mean there are lots and lots and lots of phrases in the Scripture that one can use. But I think that is probably the simplest, and it's also the one that most people have heard.

Greg Dalton: Reverend Ng?

Donald Ng: Well for me, I have always referred back to Psalm Chapter 8. Psalm 8 says that, "Our Lord is majestic in His Name." And it goes on to say that God created the whole world with his fingers and -- but then, the Psalm has questions why God would care for human beings, why God would be thinking about human beings. And it says that we are created a little lower than God. In some versions, it says that we are divine beings and we are created like angels. And that because we are co-creators with God, partners with God.

We are then responsible for all the things that God has created including the sheep and the oxen and the beast of the field and birds of the air, as well as the fish in the sea. And as Sally says, dominion does not mean violence through nature or domination or just total consumerism but rather being good stewards. And as I was reading that passage over again, I found even a new insight. It says that when human beings are responsible for the fish in the sea, it then it says, "Whatever else is in the sea," and we know that as people who are concerned for the planet earth that one of the areas that are so unchartered and yet to be discovered are all the living creatures that are in the sea.

So even the Psalm has, many, many thousands of years ago, was already envisioning the fact that as caregivers of the Earth, as good responsible stewards of the Earth, that we still have some wonderful living creatures in the seas that we can yet to discover as well as to care for. And so that's what defines for me this whole responsibility that we are not just consumers, that we're not at the end of the food chain but rather, we are with God at the beginning of the food chain, making sure that everything else are available for future generations.

Greg Dalton: And the oceans are one thing that climate scientists are very concerned about the acidification, the planktons, et cetera, and so, but there's often a perceived conflict between faith and science. So let's talk about that. Is it possible to have this faith and accept the science.

So, who would like to -- I want all of us to go down on this in terms of the rub or the alignment of faith and science. Sally Bingham?

Sally Bingham: Well, I can shed a little light on that at least in terms of the work that we do. Our Interfaith Power and Light program is focused on a religious response to global warming. Now, as a priest and not a scientist, if I'm gonna start talking about what humans are doing to the planet in terms of greenhouse gas emissions and start talking about parts per million in the atmosphere, I need scientific backing. I need to be in very close communication with the scientific community or I have no business making those kinds of remarks or asking people to drive smaller cars unless I'm well-versed on what miles per gallon automobiles are getting. So I always say that religion would not have a prayer without science. And I believe that our, in our organization, we do work with scientist and we stay as closely in contact with the facts and the science people -- what the scientists are saying about climate change is what we then put into religious language and tell to our congregants, in our constituencies.

Greg Dalton: But Don Ng, if some people accept science on climate change, then they might need to accept science in evolution and "oh, I don't want to go there." So, explain how people wrestle with that potential. Can they accept some of the science or do they reject all science because of where it might lead them?

Donald Ng: I would say that some of the best scientists are Christians, who are religious leaders themselves.

I have always understood that religion and science do not have a conflict, but rather, scientists are partners with all of humankind to understand the beautiful world that God has created in the first place. I think when science and religion end up being in conflict is when religious leaders begin to read Scripture in a very literal fashion. And I prefer that -- to say that our Holy Scriptures are written totally, completely inspired by God, but not necessarily to be understood from a literal standpoint, and I know that even some people in my own church may disagree with me on this, but to believe that Genesis 1 is exactly the way we, in the 21st century, read it as to be, for example 24-hour days, I think is somewhat naïve. And so I believe that science and scientists have helped us to see how our world has come to be and that there should be a constant dialogue between the scientists and the religious leaders so that we can understand how discoveries can inform each other. So I don't see a conflict that you refer to Greg, but I do know that there are many in our religious communities that would.

Greg Dalton: So you don't, but some do. So, but Sally Bingham, some evangelicals will say that just the notion that individuals can change God's creation, that's a troubling concept.

Sally Bingham: Well, I was actually told once by an evangelical who teaches Sunday school in Colorado Springs, Colorado, that what we were up against when we were talking about climate change, to the very conservative right wing evangelical community, that they teach in Sunday school that you as a child will hear about science.

"But understand that the world really was created in seven days -- the Scripture says so," because they take Scripture literally, "and listen and be respectful. But the word of God is what's in the Scripture and that's what you should believe." So what this fellow was telling me is that if we push science on this very conservative -- which is a small community of people, it's a loud voice but it's not as huge a group as one might imagine. But if we were to push science of climate change onto this community and they were starting to accept it that their entire theology might unravel because they would have to accept -- they can't just take science in segments. They're either gonna accept science or not. And may I just say one other thing too for the --

Greg Dalton: Sure.

Sally Bingham: -- for the benefit of people who are struggling with how to understand Scripture, I like the way you describe, Don, the -- it's kind of a story, Scripture is a story or metaphor for how we might live our life but not to be taken literally. When I was in seminary and we were having this conversation, our professor said, "you remember as a child playing telephone and you would -- somebody would whisper something to the person next to them?" The Book of Genesis is oral history and if you say something to me and I say it to you and you say it to Greg, by the time Greg gets it, it's a little different than what it's started out here.

And that's what our oral history and that's where the whole Old Testament came from and the new one also. These were all oral history. These are all stories that people told and then how they got written down inspired by God but not literally written by God.

Donald Ng: And most of the time, religious communities, those who are in a minority and very conservative in their outlook would just take that issue of creation for example, and make it into a huge controversy, and they forget -- whether you're on a conservative end or the liberal end -- we all forget that the main point of the whole chapter of Chapter 1 as well as Chapter 2, and that is that God created the world. And that we are to live in harmony with each other, caring for each other, not just as human beings but for all of God's creations.

So, those who walk with four legs as well as the nature, the physical environment in which God has created. And if people from all extremes, if we want to say, can come together and realize and still give praise and glory to God for God's mighty creation, I think we would be in a much better place than to be stuck, if you want to say, on this -- in my opinion, more morally trite issues.

Greg Dalton: If you're just joining us, our guests today at Climate One are Reverend Donald Ng from the First Chinese Baptist Church in San Francisco, Rabbi Yonatan Neril from the Interfaith Center for Sustainable Development in Jerusalem, and Reverend Sally Bingham, the founder of Interfaith Power and Light. I'm Greg Dalton.

Let's talk about some of the interfaith work that's happened around creation care and climate change. A lot of the religious community around the world has come together to say we're jointly concerned about stewardship.

We've come from different traditions but we have these similar concerns. So, Yonatan Neril, let's ask you -- I'd like to ask you about some of the work you're doing in Jerusalem with people from different faiths and teaching them about stewardship.

Yonatan Neril: Great. So, I'll mention a few projects. First, we hold an annual interfaith environmental conference in Jerusalem which brings together religious leaders based in the Holy Land together with world religious leaders via video addresses and each -- we capitalize on the high concentrations of religious leaders living in the Holy Land together with the high concentration of foreign media based in Jerusalem, perhaps more than any other city in the world, and we invite the general population and the journalists to witness how Jewish, Christian and Muslim religious leaders are coming together on the issue of environmental sustainability.

We have a second project that works with seminary students, Christian, Muslim and Jewish, seminary students who are studying to be rabbis, priests and imams and we do a bi-monthly seminars with them on topics of faith and ecology at the Jordan River and the Dead Sea and looking at issues of climate change and water in the Holy Land. And then we have third project called the United Planet Faith and Science Initiative which brings together leading scientists along with leading religious leaders like Archbishop Desmond Tutu, and we try to bring faith and science together and to show that there's not a conflict, especially when the leaders of world religions are being vocal about the need to protect the Earth.

Greg Dalton: And we'll get to the others first but I want you to come a little bit about sort of an Islamic environmentalism 'cause we don't have an Islamic voice up here, but there is a video on your website that speaks to that. So just tell us a little bit about how they approach that.

Yonatan Neril: Okay. Great. And actually there's -- since you mentioned, we have a video collection on our website of about 40 videos of faith leaders speaking about ecology from many faith traditions including Buddhist and Hindu and Native American. So, at our conferences, we've had imams and sheikhs speaks about Islam and ecology and talk about the Khalifa, which means "stewardship" in Arabic and the basis in the Koran for many environmental teachings and the importance of conscious consumption during Ramadan and other environmental practices.

Greg Dalton: Great. And Sally Bingham, you've been a pioneer in interfaith work around stewardship and climate change. So tell us a little bit about some of the recent things you've done to bring interfaith leaders together around climate change. There's a lot happening around Copenhagen in 2009. What's been happening right now?

Sally Bingham: Well, one of the most interesting things about the work we're doing, we started out as a religious response to global warming, and it was really an unintended consequence to have Jews, Muslims, Christians, Baha'is, Buddhists and all these different denominations sitting around the same table saying, "We agree. We are the stewards of creation." I don't work -- I wouldn't say that my work is interfaith collaboration, but that's what happened, and that's what's very exciting because you have these different denominations agreeing on something when they are often at odds with one another. So this has been a very unifying subject to be working in.

Greg Dalton: And I believe you -- a number of people wrote to the U.S. Senate in about three or four years ago. You got a bunch of people that came together or was that when there was actual live policy in Washington D.C., if I'm remembering correctly?

Sally Bingham: When we had a religious leaders climate summit right here in San Francisco --

Greg Dalton: Right.

Sally Bingham: -- in 2006.

Greg Dalton: Okay.

Sally Bingham: And we had -- they headed a board of rabbis.

We had an imam from Washington who is the -- he runs the North American Islamic Society. We had a presiding bishop from the Episcopal Church, we had Joel Hunter, a wonderful evangelical pastor from Orlando, Florida -- there were 15 heads of denominations who came to San Francisco, listened to Steven Schneider, who is one of our -- unfortunately deceased, but climate heroes from the scientific world.

Greg Dalton: That teacher that Yonatan studied under.

Sally Bingham: Well, Steven gave a three-hour presentation to these religious leaders, and then we created a document, signed it and sent it to Washington.

Greg Dalton: Okay. And is that voice being heard now?

Sally Bingham: I believe so. I mean, we have an annual conference. The Interfaith Power and Light folks get together every year in Washington and go to the Hill and we've done it enough times now, it's been ten years that when we're walking the aisles in the Senate building, people will say, "Here comes to the Interfaith Power and Light people." And we're also very well received when we go in to visit our legislators because they will say, "The land people come, the environmentalists come, the people for advocating for children's rights come to visit us, but we've never had anyone from the religious community." And they're very receptive to our messages because we're not coming from anything other than a deeply rooted in theology perspective, and they like that, you know. They're willing to listen to us about moral responsibility. And that's the voice that religion brings to this dialogue.

Greg Dalton: Even politically conservative climate-denying politicians? Do you go only see the friendly politicians or do you see ones who were more skeptical?

Sally Bingham: It's a great deal more fun to go and visit the more skeptical ones.

And we do visit them, and they do see us.

Greg Dalton: Do they change their vote to change their opinion?

Sally Bingham: I have to say I hope so but -- I mean many of these folks have changed their opinions. I mean, they've gone from actually being climate skeptics to being advocates for climate protection, but they've also gone the other way. I mean one of our very well-known political parties has had several people who were climate protection advocates who, in the last six or eight months before the elections, switched to the other side. I don't think we as religious leaders, at least at Interfaith Power and Light campaign, can take responsibility for either one of those changes. But I do think we raise awareness and I think talking about moral responsibility, it catches people.

Greg Dalton: Reverend Ng, I want to get you in here -- do the Baptist get involved in the policy politics or you just stick to other realms?

Donald Ng: I wish more Baptists get involved in politics if not collectively, at least individually. But I think we do. Our church is located right in San Francisco Chinatown. And we've done a number of things that we believe have helped our community and our world to be greener. And so I think as a local church pastor, my responsibility is to help a congregation become a model church so that other churches can also learn from us. A few years ago, we installed solar panels on the top of our church roof -- rooftop, and we've gone to our local ecumenical council and have actually said, "Come and learn from us."

And since then we've had two or three churches who brought their governing board and see what our church has done. And so we feel that as a local church and a neighborhood, our responsibility is to influence others that they could also do it. And so --

Greg Dalton: So you're not paying any electricity bills now, right?

Donald Ng: What we -- we used to have -- pitched you an e-bill somewhere between $500 and $600 a month. We've been paying less than $100 now and that's just on natural gas so that we could cook breakfast on Sunday mornings. And one of the things that we did, which I'll just take a few minutes, when we installed the solar panels, we worked with -- obviously, a company that installed the panels, but part of the agreement that we made was that we wanted to have a website and it's called Sunny portal with SMA, and so when people come to our church website, they could actually click a link and go to this Sunny portal website, And on an hourly basis, you can see how much energy we are creating, how much CO2 emission we are avoiding, and how much money we're actually earning because we are now contributing electricity back into the grid.

And so by doing that, we hope that more and more faith communities would see that solar panels and solar energy is achievable, and the savings that we have made are -- these resources can go into other forms of ministry.

Greg Dalton: But when you are raising funds and that solar program started from, with a bequest by one of your members --

Donald Ng: Yes.

Greg Dalton: When you raise money for it, were you concerned that raising money for solar panels might take away from ministry funds?

Donald Ng: I've always operated with the understanding that when we are doing the morally right thing, God will bless us beyond our imagination. And so I believe that as a community, we know that that was the right thing to do. And if it were going to generate less money for our annual budget, we would deal with that but actually, it's just the opposite.

Greg Dalton: You're saving money, yeah.

Donald Ng: We're not only saving money but we know that when we are doing the morally right thing, people gravitate, they get excited about what we're doing and they want to join us. And so every time we've taken this leap of faith to do something that is according to what we believe is God's calling, we have been blessed in many, many more ways.

Greg Dalton: But Sally Bingham, not every congregation is that way. Some do worry about raising money for that clean energy project will take away from problematic fund.

Sally Bingham: It's true. And I think that they -- it's a fair thing to worry about. I don't think that that's necessarily true. I think it's more -- what Don is saying, I think that if you have solar on your roof, it enhances your building, which helps your parishioners understand your congregation is doing the right and moral thing, you will bring more people into your congregation and make it even easier to raise -- well, one thing you're doing with the solar on the roof, you're saving money that can go back out into your other ministries. And often, it just has to be proven, you know, someone has to make that step and take the risk.

And I wanted to say one thing now, that you may not realize that you are involved in politics because I'm a big believer that people vote their values. And we always encourage them to do that on our website. But if your parishioners are understanding that not only is your church saving money, but you're doing the moral right thing by having solar on your roof, won't they then want to have solar on their roofs in their homes and then won't they say, "Maybe we should be electing officials who like or who are in favor of tax credits for solar." And eventually, we can have a whole renewable energy constituency that comes right out of the faith community because the church served as an example to the community.

Donald Ng: You see, that's exactly what has happened. We have -- we actually have two homes now that also have installed solar panels in their home because they see that the church can do it. You see, stemming from the Psalm 8 passage that I referred to earlier, if we are truly created little bit lower than God or divine beings or angels, we have in our own being the understanding of what is right and wrong. But quite often, when we are by ourselves, we default if you want to say, back to our less divine sides. It's like, when the cat is out, the mice play. Right? But when people belong to a faith community, we hold each other accountable. We could preach all we want to individuals and say, "You know, you need to get solar panels, you need to recycle, you need to do all kinds of green things."

Donald Ng: But when we are doing this together as a church, the whole is greater than a sum of its parts. And we then model for each other. We hold each other accountable, saying, "What are you doing at home and what are you doing in your workplaces?" And so what -- so the Church itself, or at least, I hope all churches, are modeling a lifestyle, a life commitment that is better or more morally correct than what each person can't do individually. And so, whether on a weekly basis or on a regular basis, when people do come to a faith community, they kind of get recharged. They learn once again whether it's morally right so that in the other six days of the week, they can do the right thing.

Greg Dalton: And so you believe that individual action matters. Because a lot of people say -- laugh, "You know, if I cut my carbon to zero or even if everyone in the United States cut their carbon to zero, the world would still have a problem. So what I do is insignificant." And you're saying that individual does matter because --

Donald Ng: I do believe that the accumulation of our efforts do matter. But I think ultimately as a religious person -- a leader, what I do in regards to my own conscience matters first. Everyone has to live with himself or herself and to say that we've made a difference, one by one, I do have hope and I believe that all things will be made new. There is gonna be a new heaven and new earth, and that's what we have faith in.

Greg Dalton: And you became a vegetarian also as part of the process.

Donald Ng: Oh, yes. I became a vegetarian because of what I just mentioned about the discovery of God's word and that if I -- are going to talk about this from the pulpit, I have to be conscientious about what I do as an individual. And therefore, being a vegetarian means that I would not cause violence to God's creation including what is necessary to sustain my life and my lifestyle, and I too have converted a number of people to becoming vegetarian, and once I started talking about why I am vegetarian based on conviction -- and that's important. It's not because dietary or even the love of animals but basically from a Scripture standpoint, I can see why -- I'll say this, Christians should be made -- I mean, they should all become vegetarian, as my crusade right now. But thank you for introducing that, Greg.

Greg Dalton: If you're joining us, our guests today at Climate One are Reverend Donald Ng from the First Chinese Baptist Church in San Francisco, Rabbi Yonatan Neril from the Interfaith Center for Sustainable Development in Jerusalem and Reverend Sally Bingham, Founder of Interfaith Power and Light.

Sometimes, with individual action, people can buy a Prius, become a vegetarian and think start recycling and think, "I'm good. Okay. I'm doing my part," and then not go any further. They have addressed their conscience; they can respond to their children or at a cocktail party, "Yeah, I'm good," and then don't go any further. So I'd like to talk about how we could continue people on this path of continual improvement, enlightenment, et cetera. Yonatan?

Yonatan Neril: Also, I would say that my organization has a branch called Jewish Eco Seminars and we have on our website, Jewish environmental teachings on 18 specific topics as well as teachings according to the weekly Torah portion that really tried to bring it from this theology to practical action.

But I would also say that the environmental crisis is not a crisis of the environment per se. It's not a problem with the rainforest or the bees and the birds, the trees and the toads. The environmental crisis is actually a spiritual crisis and -- meaning it's a crisis of how we live our spiritual beings in a material reality -- consequently. A lot of the changes that I believe that religions can be most effective and encouraging is our spiritual changes. I mean it's not only at a level of what type of car do I drive or do I drive a car, or what type of food do I eat and where does it come from, et cetera. I believe that a lot of the imbalances that we're seeing in the global environment are actually stemming from imbalances that are occurring at the individual level within billions of human beings. And so like Reverend Ng is saying, the correcting and our returning to balance within ourselves and our finding spiritual contentment as the greatest source of our pleasure and weaning ourselves away from finding our greatest pleasure in material satisfaction, then that shift, that reorientation is a tremendous environmental act. Even if it even if at that moment, nothing changed in terms of how I consume things, but something changed inside. And as a result, the whole rudder of the shift changed, and then the direction itself will change.

Greg Dalton: Reverend Bingham?

Sally Bingham: I think that is so right on. It's almost as if -- and I think, Greg, you had this experience yourself when you went off to find out, is the climate problem really real and you have a sort of epiphany.

There comes a time when you shift internally about the way you're living. So you wouldn't stop with just getting a Prius because it's -- if it really is a shift that you realize, "I matter. I matter to God. I matter to my neighbors, and every single one of my behaviors matters. Whether it's the coffee I drink, the clothes I wear, the car I drive, the energy I use, the food I eat, all of these things matter." And then you're thinking, your spirituality, your values, who you are as a person, go through a shift to where it's almost unconscious and you're not throwing thrash out the window or driving your car unnecessarily because you have this sense that everything I do matters.

Greg Dalton: Right.

Sally Bingham: I matter and my behavior matters. And I think that the person who buys a Prius and says, "Okay, done," that's not the spiritual renewal that you're talking about or that you're talking about. When someone has that epiphany and recognizes we have to change the way we are in the world as humans and stop thinking of ourselves as dominators of nature, then your whole behavior, your whole being shifts -- the way you are as a person in the world shifts.

Greg Dalton: But you're about to -- that's all good and that's very interesting but you're also about to switch from a small gas-powered car to an electric car. I want to make sure we've mentioned that. So you're continuing to that internal as well as the thing because some people, the spiritual realm is accessible to some people and some people still operate on a material level where things that are concrete and specific, it's easier for them to grasp onto as a place to -- as a place to start.

So Sally, I want to hear about your new electric car.

Sally Bingham: Well, I don't have it yet but I'm on the list.

Greg Dalton: When it's gonna be?

Sally Bingham: No. It's good. I have a Smart ForTwo car but they're going to be out in the market to get an all-electric Smart ForTwo car starting in January, and I'm just taking one step further to get off gasoline.

Greg Dalton: Excellent. Before we're gonna get to our audience questions here, I want to ask about forgiveness. We had a scientist here recently, Dr. James Hansen, who talked in very strong terms about people in the oil industry who -- and in the fossil fuel industry who knowingly extract fossil fuels and burn them in a way that they know can be harmful, and I want to know how you think about forgiveness for people who are continuing in this fossil fuel model with the science these days, it's pretty clear what the consequence is for their children and all of us are. So, Yonatan, you know, forgiveness in fossil fuels.

Yonatan Neril: Well, I think that the Creator of the world will hold that there is a level of responsibility that we need to take -- in regards to our Creator, regarding every pound of carbon that we put in the atmosphere, especially when for 40 years, scientists have been saying that that behavior is one that's not sustainable for this planet and human society. And so, it's also important to have compassion and to realize that each one of us is embedded within a carbon culture and within industrial and post-industrial society.

And virtually everything we do, in some way, whether it's drinking a cup of water that's been pumped using an electric pump or et cetera -- virtually, everything we do has a carbon footprint, has an ecological footprint. And so, I will -- for me, there's a teaching of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov, a Hasidic rabbi who says that "We need to -- remember that we're going to cross a very narrow bridge but the important thing is not to make ourselves afraid. And that in our generation, we are facing very daunting challenges and very significant challenges and opportunities ahead." The important thing is not to be afraid and not to be judgmental toward other people but at the same time, to remain true to our convictions that we can access our millennia-old religious traditions to promote the betterment of humanity. The greatest renewable energy available on this planet is spiritual energy, and I believe that the Creator calls on us to access and to harness that energy for the betterment of humanity.

Greg Dalton: Reverend Bingham or Reverend Ng?

Donald Ng: Well, I'll respond just briefly. I mean, we live in such a polarized world and certainly very conflictual even in the U.S. And you know, there'll be a time when we hope, as all religious communities do hope, that there is peace and harmony in the world. But until that time comes, we as human beings need to always reach out to reconcile the broken relationships that we have. And unless we can show forgiveness and understanding and bring people together to work on legislation that will make a difference --

Donald Ng: -- bill -- lives that will model for others in future generations that these good behaviors that we can all learn from and so that, you know, the global warming can be at least held at bay. All these kinds of efforts are worthwhile but it won't happen unless there is reconciliation. And so forgiveness is a part of that process of working together across all kinds of tribal groups.

Greg Dalton: Let's go to our audience questions. Yes, welcome to Climate One.

Male Audience: I'm pleased that you're all on board with climate change. I learned about climate change in 1960 in an ecology class at UC Davis. It's been 53 years since I've heard people of the faith-based community open, and I'm a little concerned about the Southeastern United States and we're living in a bubble here, so it's easy to talk with a faith-based community about climate change. How are we gonna talk to the Southeastern United States and get them on board so that we can move this country forward? And that group is holding us back with all the strength that they have.

Greg Dalton: We'd like to take -- tackle that one, how to communicate with people who are skeptics. Yonatan?

Yonatan Neril: My organization is reaching out to several evangelical programs that are based in Jerusalem to try to reach their students who are studying -- some of them are studying to be clergy and to try to engage them on ecology and the Holy Land. So, that's one way that we're trying to do it. We're also, as I mentioned, we have this video collection as well as a short videos of world religious leaders speaking out on ecology.

The Dalai Lama, Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, Patriarch Bartholomew, others -- and we're also aiming to have evangelical leaders involved. Our hope is that as more and more people see that the -- sort of the body of world religious leaders are speaking out on this issue along with scientists, that it will be hard to deny that there is something very real about it.

Greg Dalton: But probably what you said is, you're talking with, the next generation and there's some people who say, "Look. In any industry, whether it's business or faith-community, that the baby boomers, certain generations, aren't gonna change a whole lot. That this -- go -- younger, it's gonna be a generational change. Reverend Bingham, I'd like to get you in on that too, in terms of talking to people, evangelicals in the Southeast.

Sally Bingham: Well, I don't think it's quite as dire as the question, the gentlemen who asked the question. We do work -- did you say the Southern United States?

Greg Dalton: Southeastern.

Sally Bingham: Southeastern United States. We have programs there. We have a very robust program in Georgia and in North Carolina, and they're making a wonderful headway by religious leaders talking about these issues from the pulpit. And what we're trying in some cases to do is begin with what we have in common. I mean, everybody wants clean air. We want a healthy environment for our children. And if we start there and start talking about how are we going to have clean air and a healthy environment for our children, well, we're gonna have to switch over to renewable energies. And people are beginning to realize that. And if we have any more major super-storms like Sandy which has done an amazing amount to raise consciousness about how climate change is actually affecting the weather as well. I mean, I'm a big believer in the human spirit and the fact that once enough people recognize this as a problem, we will make the changes we need to make.

And I think this individual matter behavior matters. I have to go back to one quick thing though.

Greg Dalton: Sure.

Sally Bingham: Does one offer forgiveness to the fossil fuel industry before the fossil fuel industry asks for forgiveness? In other words, I think they're committing crimes against humanity. If they're doing what they're doing, knowing that they're doing it. But I haven't heard a fossil fuel industry ask anyone for forgiveness. And I'm wondering where --

Greg Dalton: Well, we -- you could blame the companies but we ultimately are burning it. We're consuming that product. So, are we committing crimes against humanity or just the companies that sell it to us?

Yonatan Neril: Well, I want to actually mention that -- see, that's one of the incredible things which is related in a teaching about the generation of Noah. And that was -- when the whole world was destroyed except for everyone on Noah's Ark, so there's a Jewish teaching that everyone in the society would go to the market and steal one peanut. And because it was such an inconsequential act, no one could be tried and the whole society collapses. And so for that, the world was destroyed. And in our times, does anybody desire that there'll be climate change? Does anyone want the rainforest to be destroyed? Does anyone desire any global environmental issue? Of course not.

But at the level of the individual, each one of us contributes a little bit here, a little bit there and that, and that -- that's why I think that ultimately, I mean there is some, there is some things going on in the fossil fuel industry but ultimately what's driving this is not the fossil industry. It's the material desire of the human being which has been spread to billions of people.

Sally Bingham: Consumers?

Yonatan Neril: Yeah.

Greg Dalton: Let's get our next audience question. Yes, welcome to Climate One.

Female Audience: Thank you. You've all been very inspiring and thought provoking this morning -- afternoon.

I come from a church near the Central Valley and we're about to embark on a change in our building. I'm chairing a study committee and I'm about to present some recommendations and I'm just wondering, we'd love to incorporate some Earth-friendly ideas. I -- is there a place where I could go and get some information for ideas and maybe even equally importantly, is there any financial assistance available throughout the religious community for older churches who want to retrofit and become more environmentally conscientious?

Greg Dalton: Sally Bingham?

Sally Bingham: Well I hope that you will go immediately to California Interfaith Power and Light, and there are people here today who can give you lots of information on energy efficiency, green building. I also spotted an architect out there who knows an awful lot about green buildings -- and in terms of financing, I think there are ways to find financial help but most often, a congregation has to see the advantages of long-term thinking. And when you change out your light bulbs to a compact fluorescence and you see your energy bill go down a little bit, save that money and put it into something else. And then, your savings begin to grow to where you can actually make the changes. And sometimes you have to spend money in order to save money. But there are lots of people here that can help you and I'm sure as soon as this is over, you'll be hearing from them.

Greg Dalton: Thank you for that question. Right. That shouldn't have to reinvent that wheel, we have lots of churches have already been down that path. Hi. Welcome to Climate One.

Female Audience: Thank you. Thank you very much for all of this discussion. It's been very interesting to me.

I am living in a material world, not necessarily in your world. But I was wondering, you know, Bill McKibben, who's recently been in town where he's discussing an approach to get people and organizations to divest from the fossil fuel industry and at the university level, perhaps at the, you know, other levels. And so I wondered if you have an opinion about this and whether you thought that your congregations could provide some impetus behind this.

Greg Dalton: An area we haven't touched on. It's where congregations invest their money using that financial leverage as a tool against fossil fuel interest. Reverend Bingham?

Sally Bingham: Well, I think it's a very good idea that -- it certainly worked during the apartheid time, and I know when the Episcopal Church has a committee on socially responsible investments, it's not -- and so there are denominations who are looking at that and -- we know and work with Bill McKibben and collaborating on a lot of his initiatives which are I think quite beneficial and he also is one of the heroes in terms of raising awareness with young people about the climate issue. It's not something we are involved in particularly. We have so many different programs and we're trying to work at the grassroots level to do what Reverend Ng is doing, in getting congregants and people involved in a whole movement to get Americans to understand that this is an enormous problem.

We have not gotten involved in divesting. I think it's a good initiative and I hope it works and I will support Bill McKibben in doing it. Congregations themselves don't usually have enough money that they have investments anyway. The denominational heads do.

I mean, the Catholic Church does, the Episcopal Church does. Individual congregations don't have -- managing -- financial portfolios that I know of.

Female Audience: Encourage your congregants to do it?

Donald Ng: Yes.

Greg Dalton: Reverend Ng?

Donald Ng: In a similar way, the American Baptist Church is, in the USA, is about 5300 churches across the country including Puerto Rico, and we do have national policies and guidelines about responsible investing. And we're very clear about certain kinds of companies and corporations that we stay away from, and then others that we are very free and more openly are involved in, in order to help them accomplish their mission. And so that is the view by our denominational leaders on a regular basis.

Greg Dalton: Let's have our next question. Yes, welcome.

Male Audience: Thank you. Going back to that first question, I fear that the -- that was back -- that was Reverend Sally's thinking that the numbers are small but the climate deniers and skeptics are pretty large, and in fact from what I've read, there are millions perhaps of folks in the religious communities, especially Christians and Muslims that believe in this apocalyptical deep belief like end times, the rapture or whatever, that the Lord is gonna come down and take all the believers to a better place, leaving the rest of us. And I'm just wondering if you've engaged such folks and how, if any arguments might be made towards them, and then a quick second question, whether your denominations are getting behind it all of carbon fee as a potential resolution of the climate disruption issue.

Greg Dalton: So the rapture, we'd like to tackle that one.

Donald Ng: Why are you looking at me? [Laughter]

Greg Dalton: 'Cause -- Reverend Ng?

Donald Ng: Well, certainly, as the guest mentioned, we do have Baptist churches that believe in the end time theology, and with that perspective, they take the physical world as perhaps secondary and not as important and that everything will kind of work themselves out at the end times when Christ returns. Obviously, I don't share that theology that if time does come to an end, it's certainly not gonna be the way it's been portrayed by TV and movies. I guess I would come at that question from this point of view. I often say in our Church, there is no such thing as undisciplined disciple, that the word disciple means that you are a disciplined person. You have to live a faith that is -- you know, you have to walk your talk. And if God is the one who is the Creator all things on Earth, then God provided provisions for us and therefore we must provide provision for future generations until that day comes. And that quality of life is not just for our own generation's sake. But if that time does come, we hope that there'll be many more generations of quality life on Earth that could be available.

And so for those who claim that they could predict the time when that all happens, I think they just -- it's their figment of their imagination, I believe, and so as long as I'm living and I'm using fossil fuels as we mention, you could be as responsible as I can for the future.

So I don't know -- I mean when you argue with people like that, there's no solution. I mean they hold to their beliefs, but I hope that others can see that that is not the answer as to think that the end doesn't come.

Greg Dalton: Reverend Bingham, then we're gonna get to try to wrap up here. We got just a couple minutes left.

Sally Bingham: Just very quickly. We have a great many friends in the evangelical community, and Richard Cizic who some of you may know that name, have said that anyone who things that it's okay to destroy creation to bring Jesus back, is really committing blasphemy, and that there is absolutely nothing in Scripture that supports destruction of creation to bring -- for the rapture. And that is, as he said, who is one of them, I mean, he doesn't believe that theology but he does come out of the evangelical community. He said that that is a very loud but small minority voice in this country. And I travel all over the country, no one has ever approached me and said, "We're supposed to wreck the Earth and bring Jesus back."

Greg Dalton: Let's have our next question. Yes, welcome to Climate One.

Male Audience: Collaborating on your comment about Noah's Ark. There was a time when God almost destroyed mankind. And that raises the question whether A, whether that could happen again; and B, if the whole issue of what's happening with climate change isn't God's way of saying to man, "Look, I don't have to do it again. You're doing it yourself."

Yonatan Neril: Right. So, the --

Greg Dalton: Reverend Neril.

Yonatan Neril: The symbol that God gives after the almost complete disruption of terrestrial life is the rainbow. That is the symbol of the covenant between God and people, between God and the Earth. So Nachman, in his writing in medieval Spain teaches that that symbol of an ark in the sky is actually an ancient symbol of a side that wants to show that it is stopping to make war. That the side that wants to make peace would put the arrow, they will put their bow into the sky and put their bow upside down, and that's an ancient symbol.

Now, according to that, God was in a sense making war with the Earth. God was destroying the Earth and shooting arrows down and so God reversed as it -- you know, in the metaphor, God's arrow. So, to with us, Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, Chief Rabbi of the British Commonwealth teaches, so there's an implicit opposite arrow that is for us and implicit -- the second half of the rainbow is for us, that we need to take responsibility and not destroy the world ourselves. And if we do that, then we really fulfilled the covenant that God created with us.

Greg Dalton: We're at the end here but I just want to give Reverend Bingham and Reverend Ng, any chance for a final word.

Sally Bingham: Well, my final word is that you haven't mentioned my green color. [Laughter]

Greg Dalton: Oh, well let's mention you're a green color.

Sally Bingham: I normally wear a white color obviously, and most --

Greg Dalton: Would you forgive me?

Sally Bingham: -- clergy do wear white colors. [Laughter] But I thought that this was so representational of the work we do. I mean I'm a green color worker promoting green colors and I took an old one that was kind of rad-dy and dyed in green and I think you think I put it in the wash with the dark clothes or something. [Laughter]

Greg Dalton: It's possible. So, please forgive me. Reverend Ng, last word.

Donald Ng: My last word is that during the Christmas season, we love to sing that Christmas carol, "Joy To the World." This year, I became much more conscientious about what the words have to say. And it clearly says that the second verse specially, joy to the Earth and heavens and the flood -- the field and floods are all are we repeating sounding noise of joy, because God comes in to the world not just to redeem human beings but also to nature. That's why the chorus says, "Heaven and nature sing." And for me, as I sing that Christmas carol, that's always going to remind me that it's the whole world that God loves.

Greg Dalton: Heaven and nature sing. Well, that will lead to end. Our guests today at Climate One today, Reverend Donald Ng from the First Chinese Baptist Church in San Francisco, Reverend Sally Bingham, founder of Interfaith Power and Light, and Rabbi Yonatan Neril, founder and executive director of the Interfaith Center for Sustainable Development in Jerusalem. I'm Greg Dalton. Thank you for coming and thank you for listening on the radio.

[Applause]

[END]