American Turnaround

Guests

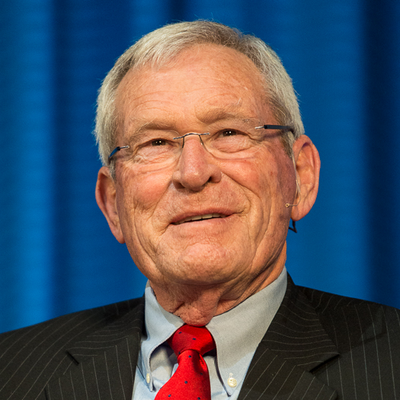

Ed Whitacre

Summary

No private investor in the world would put money into General Motors when it was going bankrupt, says former GM CEO Ed Whitacre. “The government did exactly the right thing” bailing out the company. The politically charged electric Chevy Volt made headlines during Whitacre’s tenure at GM, but in spite of the political hits the car took, Whitacre believed and still believes that “there’s a real future for electric vehicles.” To Whitacre, the Chevy Volt is an example of “a responsible corporation attempting to do the right thing and explore new technology.” As American manufacturing moves forward Whitacre believes we need to accept that “it’s a global economy” and adapt to it. A conversation with a global CEO on General Motors about his role in the 2009 bailout and the state of American manufacturing.

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: Welcome to Climate One, a conversation about energy, economy, and environment. To understand any of them, you have to understand them all. I'm Greg Dalton.

Four years after a near-death experience, General Motors is well and on the road to recovery. It is profitable again and the U.S. Treasury's gradually selling its stake and the company. The GM bankruptcy and bailout is one of the great stories in the annals of American business. And over the next hour, we'll discuss that with our live audience here at the Commonwealth Club at San Francisco. We are pleased to have with us Ed Whitacre, former chairman and CEO of AT&T and General Motors. As the automaker emerged from bankruptcy in the summer of 2009, he became chairman of GM, and in January of 2010, was named CEO -- a post he had until just before its IPO later that year. Please welcome Ed Whitacre to Climate One.

[Applause]

Ed Whitacre: Thank you, Greg. Thank you.

Greg Dalton: And before we begin here, I have to offer disclosure that General Motors is a supporter -- financial supporter of Climate One and the Commonwealth Club. And let's fix your ear, see if that --

Ed Whitacre: I don't know what the shape on the ear or something.

Greg Dalton: We're going to get another microphone perhaps that we might use, a handheld if that doesn't work.

So let's begin the story of your involvement with GM. You're happily retired and you get a phone call from the car czar -- so tell us what happened when you got that call from Steve Rattner.

Ed Whitacre: I got a call from Steve Rattner, who was the car czar under the Treasury Department.

And he said, "Ed, I haven't seen you in a while." It'd been 10 years since I'd seen him. And I had known him in New York in financial circles, and he said, "I'd like for you to think about becoming chairman of General Motors." I said, "I don't know what you think about cars. I barely know how to start one. I'm a General Motors owner but I don't know anything about it." And he said, "Well, you know, the company is very important to this country. It needs some good leadership. You've run a big company, a unionized company, and you don't know anything about the car business and that's good." And so I said, "Well, Steve, I don't think so. I'll talk to you later."

He called back the next day and made the same proposal to me. But then he began to put it in words about this would be a great service to the country and how much the country needed GM. But to my credit, I still said no. Well, he called the third time and he got to me that time and I got to -- my patriotic duty I guess got to me, so I finally said, "Yes, I'll come do it." But it took him a week to get me. But it was good, I said yes.

Greg Dalton: And then when you got inside the company and you went to meet the CEO, Fritz Henderson, and you walked into his office and you asked him for an org chart. Tell us about that meeting and that encounter.

Ed Whitacre: Well, Fritz Henderson was the newly appointed president of General Motors and was in charge, and I walked in and said -- I was a newly appointed chairman, I said, "Fritz, I'd like to see the organization chart for General Motors -- who reports to who and what the different departments are." And there was no organization chart.

And right away I got a clue, maybe things weren't going to be like I thought they were going to be. And I said why no organization chart or something to that effect. I sort of got the answer. "We cut out a lot of human resources functions to save money." And then some other things. But nevertheless, there was no organization chart to be had.

Greg Dalton: And you asked some executives at that time why GM fell into the ditch, why they went bankrupt. And what was the response of some of the people?

Ed Whitacre: Well, astoundingly, some of the senior management at GM I asked the question what went wrong here, and the answer was from some of the senior management, "We didn't do anything wrong. The economy got us. But we did nothing wrong. We're General Motors, it's impossible to fail, we did nothing wrong." But as we all know, I asked the question then, "Well, what about Ford and what about Volkswagen and what about Toyota, Nissan, a lot of other --" there was really no answer for that. But the prevalent feeling in upper management there was "we did nothing wrong, the economy got us."

I think that's the best way I can describe it, Greg.

Greg Dalton: And what about the board? The board also was responsible presumably for not only hiring the chief executive, Rick Wagoner, at that time. What do you -- what would you think the board responsibility the board had for GM going off the cliff?

Ed Whitacre: Well, you'd certainly have to say quite a bit. When I got there, there were I think only four existing board members that elected to stay on the board; the others had left for one reason or another. And there were four and they were relatively new on the board.

But obviously, they had been convinced by management or had convinced themselves that GM was on the right track and would recover from the economic woes or quality woes or whatever. But certainly, the board had the responsibility.

Greg Dalton: Because it went five years without making any money.

Ed Whitacre: A long time…

Greg Dalton: A long time…

Ed Whitacre: A long time.

Greg Dalton: And then you came to the point where you decided that Fritz Henderson couldn't stay, that basically the only thing that had really changed at that time was a few board members, the CEO -- but everything else was the old GM, even though they were calling themselves the new GM. So how did you come to that decision that you needed to change leadership?

Ed Whitacre: Well, that was a really pretty easy decision to come to. And I want to say that Fritz Henderson is a very fine person. And he's a car genius and had an incredible recall of everything that had happened, everything that had gone on. But unless you're there, you cannot understand how much bureaucracy existed at GM. They had the matrix system of management, which meant that everybody had more than one boss, and therefore they had no boss. And matrix management is supposed to be collaborative, but it isn't because you collaborate so much but you never do anything. You never get anything done. You never take any actions.

And Fritz and some of the other senior managers -- very fine people, smart people -- but they had grown up in that system, Greg. And just couldn't step out of it in my judgment.

Greg Dalton: And so you came to -- how did you tell Fritz that it was his time? That you gave -- initially I think he had what? Six months to turn it around or was it 90 days?

Ed Whitacre: The board decided early on that we wanted to see a lot of changes in 90 days. At the end of that 90 days, we didn't see any changes with a lot of encouragement, help, consultations, discussions, et cetera, but not much changed in that 90 days.

And so we made a decision that we would make the most of all the top management.

Greg Dalton: Okay. And then also, Fritz Henderson at that point, he was a lifer as many were at that point…

Ed Whitacre: Yes.

Greg Dalton: -- at GM, and he -- because of the bankruptcy, a lot of them had their pensions wiped out, but you decided to hire him back as a gesture of appreciation for his lifetime of service?

Ed Whitacre: Well, as I said, Fritz was a brilliant car guy and he had a brilliant mind. It didn't seem right to me that a guy had worked there 30 or 40 years and you dismiss him with nothing. And I mean nothing. He didn't get anything. And Fritz had great knowledge, so we hired him back as a consultant for a short period of time in China, which he was well aware of what was going on in China with General Motors. But that's the reason we did it. Call it whatever you want, but it was right after all those years and he put in many hours to just get nothing. So, we did it.

Greg Dalton: Were there other people that also had their pensions go away or bondholders to pick their cut? There are other people. There's a lot of pain in this --

Ed Whitacre: Well, I got there after the bankruptcy, but obviously a lot of people and all those categories got hurt -- bondholders, certainly the old stockholders got wiped out. Everything out -- I got there right at the end of that, but there was -- there were a lot of people hurt, certainly.

Greg Dalton: You tell about another interesting meeting where you walked into the UAW. Tell us the story of driving over in your --your meeting with Ron Gettelfinger, the head of the United Auto Workers.

Ed Whitacre: Well, Ron Gettelfinger was the head of the United Auto Workers, and he had dealt with the government through the bankruptcy. And I started asking the question because I had always at AT&T interfaced quite a bit with the union.

In fact, a lot with the union, and considered them friends, coworkers, people that were part of the business just like I was. And I asked the question, "Who deals with Ron Gettelfinger?" Well, apparently nobody did or it was down in the organization. And so I got in the car and drove to Solidarity House down Jefferson Avenue, walked in to the Solidarity House unannounced. I greeted the receptionist, I told her I was Ed Whitacre, the new chairman of General Motors, and I'd like to see Mr. Gettelfinger. And things got quiet there.

[laughter]

Greg Dalton: What was the look on her face? Yeah?

Ed Whitacre: And she said, "Just a minute, Mr. Whitacre." And she disappeared and then a couple of minutes, Ron Gettelfinger came down the stairs and greeted me and we got acquainted. Went back to his office and had a nice conversation.

Greg Dalton: And you liked him? Why did you like him?

Ed Whitacre: I liked him because he had a real feeling for General Motors. And the employees there, he wanted the company saved, he wanted it to make money. I thought he had a very good feeling about GM's role in the United States manufacturing industry. He just cared a lot. He wanted it to succeed. He wanted to help. He wanted to do whatever he could. He just come away from that with a good feeling. And I did.

Greg Dalton: And what was the reaction back at the Renaissance Center at GM headquarters when they found out that you went rogue and did this?

Ed Whitacre: Well, the first thing was security got very upset because I did it on my own and you're not supposed to drive around Detroit, as I have learned by yourself. [laughter] it's not a good thing to do, and certainly you wouldn't drive down to the union hall.

But reaction was, "Well, that's never happened before," you know, "and don't do that again without security going with you," and "Oh, my God, what does this mean?" There were reactions all over the map.

Greg Dalton: And -- but you started having breakfast with him regularly?

Ed Whitacre: Yup. I did. At the Motown Diner. [Laughter] On -- Jefferson Avenue, it's midway between General Motors at the Renaissance Center and the Solidarity House, and we would meet there at 6:30 in the morning and talk about things that he could do and I could do to get GM going again.

Greg Dalton: Just the two of you?

Ed Whitacre: Yeah.

Greg Dalton: And I got the sense reading that he worked his way up kind of like you did, that you kind of identified with him in terms of your own paths -- similar paths in your respective organizations.

Ed Whitacre: I think that's right. I think that's why we made the connection. First of all, he's a smart guy and he cares a lot. And I think we had similar backgrounds, so we just hit it off and he worked with us and we worked with him, and we've got things -- that helped a great deal.

Greg Dalton: Did -- there's been some talk about -- and I understand this was a little bit before your time. But the labor, did they get a better deal than, say some bondholders in terms of the restructuring of the company?

Ed Whitacre: Well, I think they probably did. I think a lot of people associate that with politics, et cetera, et cetera. But there were a lot of union people that'd lost their jobs, too, and so I think there was a lot of hurt among the entire workforce.

Greg Dalton: If you're just joining us on the radio, our guest today is Ed Whitacre, former chairman of and CEO of AT&T and General Motors.

Was there any private capital that would have come forward? Was there options to government bailout at that time that GM was in the ditch?

Ed Whitacre: I'm asked that a lot. Was there any private money, any money from anywhere that would come in and save General Motors so the government didn't have to.

And I can tell you unequivocally, there wasn't one dime out there. Nobody -- I mean nobody in the world would put money into GM. And the government did exactly the right thing bailing out GM. And I think if you think about it, it's the largest manufacturer. Had GM gone bankrupt -- it's not only the GM employees but there were a million people employed by the suppliers to GM. And so it wouldn't have been the GM jobs lost; it would have been many times that -- millions of jobs with suppliers, car dealers -- everybody that's associated with that. So it was absolutely the right thing to do. But your answer is there was no money. No money from anybody except the U.S. Treasury. You and I really, the taxpayer.

Greg Dalton: Right. So they stepped in. Did the government meddle in the management of General Motors?

Ed Whitacre: No. The government did not meddle in the management of General Motors. One of the things we got cleared up front was if you want us to turn this around and you've charged me and I put the management team together to make this thing go, and certainly we want you here, we won't answer any questions but you got to stay out of the day-to-day management. And they did.

They were very good partners, Greg.

Greg Dalton: So they never called up and said, "That car is not so good. Go change the cup holder. That's --"

Ed Whitacre: I thought they'd follow that but they never called. They let us run it.

Greg Dalton: One of the real colorful characters at General Motors is Bob Lutz -- iconic, legendary car guy.

Ed Whitacre: Right.

Greg Dalton: Also very command and control guy. Someone who knows cars really well, and he had a very broad brief in General Motors. And he had fuzzy lines of -- responsibility, exactly what he did. How was it interacting with Bob Lutz?

Ed Whitacre: Well, I have great respect for Bob. He was a real car guy. He had worked at some other companies, Chrysler and Ford, I think -- and done some other things and he invented or put together a design to Viper and all of you know what the Viper was, it was a car made that was really fast and sleek and so forth. But Bob was a part of the culture at GM where you talk about things but nothing ever gets done.

And we had to decide -- one of the first things we had to decide at GM was what do we do here, what's the purpose of this company. And really, nobody could answer that for me. So we had the first meeting with new management and it says -- the question was, "What does GM do?" And we finally decided after a few minutes, Tom Stevens, who was chief engineer at that time said, "Well, we should design, build and sell the world's best vehicles." And I said, "Boy, that sounds good. Everybody understand that? Let's go communicate that to everybody in the company and here's what we're gonna do and we're gonna simplify and go do it." And Bob just wasn't a part of that.

Greg Dalton: We're gonna simplify for -- we're gonna switch microphones here and have you -- yeah, it's not working so well so we'll -- that's fine.

Ed Whitacre: Okay. Is that better?

Greg Dalton: Yeah. [crosstalk] --

Ed Whitacre: How does this look hanging off of my --

Greg Dalton: You can --

Ed Whitacre: Does this look like an earring or --

Greg Dalton: Yeah, I'll go and get -- [laughter] you're in San Francisco so it's -- yeah. [Laughter] It's all right. So, it didn't work out so well with Bob Lutz. You said you're not a fan of the matrix system. You're also not a fan of consultants. Tell us about some of the consultants who were running around GM and what you did about it?

Ed Whitacre: Well, my previous life at AT&T, I had seen a few consultants over the years as you might guess and then -- almost every case, they would tell you what you already knew. And I guess it was a way to prolong doing anything, and that's not true of all of them certainly. But GM had consultants stacked on top of consultants, and they would call in consultants to study something or make a recommendation. When I thought it was mostly common sense -- again, this is not everybody, but most of them. And it was a way to prolong making a decision, and so I just don't think you should pay people to tell you what you already know, Greg.

Greg Dalton: And so you had -- you cleaned out a lot of the consultants? You talked a lot about some of the senior management team and some board members and -- there's really only one woman, Susan Docherty, that was in senior management of that level. So Sheryl Sandberg has a new book out, a lot of attention about women in the workplace, et cetera. What was the culture for women executives at GM and how did you address that in any way?

Ed Whitacre: Well, I don't think there was any deliberate closure there or any deliberate actions that affected that one way or another. The head human resources person was a woman, that's a tough job. Susan was a top job, Mary Barra was a top job.

Greg Dalton: Your environmental person, Beth Lowery was over there. So -- yeah.

Ed Whitacre: Exactly. And so for whatever reason, it just hadn't happened but we did promote Lauren.

Greg Dalton: And how about on the board?

Ed Whitacre: On the board, we had very good representation for women. Very good.

Greg Dalton: The Chevy Volt was -- you wrote the Chevy Volt was a game-changer. So how was the Chevy Volt a game-changer for Chevrolet?

Ed Whitacre: Well, I think there's a real future for electric vehicles.

I don't know if you agree or disagree and certainly there's a lot to be done, but the Chevy Volt -- think companies have a responsibility to work on new technologies, and so we certainly worked on it had while I was there. But the Chevy Volt was the first electric vehicle where you didn't have range anxiety. That's the word that you use in the car industry, and that is "God, can I get back home? How far can I go and get back to where I want to go?" Well, the Volt didn't have that problem. And the Volt, I got to drive I guess the very first one of the -- or some of it. It's a very nice car. It's not range-limited. You go so far on battery then there's a nice, little small gasoline engine that recharges the batteries.

And I think it has a real future. I do think it's a game-changer. I know there are problems with distribution systems, you can't plug it in everywhere. But I think we have to continue to explore that. And I think it's a very thoughtful car. People complaint it costs too much like 30 -- low $30,000 after tax credits. But I do think it's going to catch on more and I think we have a responsibility to keep pursuing that.

Greg Dalton: It became a real political punching bag, I think that was the term that your successor, Dan Akerson, used. Why did the Chevy Volt become politicized when it's just a car?

Ed Whitacre: Why does anything becomes politicized? [Laughter] I don't know the answer to that. Some people thought we were frittering away the taxpayer's money. Some people said that technology would never work, but it did, can be improved. There's certainly a lot yet to be done in batteries, but the Chevy Volt battery's good for 10 years. It goes a long time but I can't answer why it got politicized -- why does anything, you know.

Greg Dalton: It sold 24,000 units --24,000 Volts were sold in 2012. It's one of -- even one of Chevy's lowest selling cars. Do you think that will take up -- what will take to --

Ed Whitacre: I do think it will continue to do well. Or do better. And I think the distribution system will pick up -- distribution of electricity.

Greg Dalton: Electricity -- yeah.

Ed Whitacre: -- to charge it. And I just think we all need to be responsible on climate and environment. It certainly addresses that. So yes, I think it will continue to do better and better.

Greg Dalton: And you wrote that the Chevy Volt was not about making money. It was about sort of atoning for General Motors killed the first pure electric car. It was also brand restoration for General Motors to --

Ed Whitacre: There was no atonement there.

Greg Dalton: Okay.

Ed Whitacre: That's a wrong word, Greg. What it was, I think, was a responsible corporation attempting to do the right thing and explores new technology and continue to explore -- and I think GM will do that as well as other manufacturers continue to do that. But it's just an effort to find a new propulsion system that's friendlier to the environment, climate, et cetera.

Greg Dalton: And you think there's -- you said there was promise for EVs. Do you think it will become more than a niche? That they will become more than an urban car for people on the coast? The EVs will be for the mainstream American market?

Ed Whitacre: Well, I'm not sure I have the answer to that, but I think it will gain in popularity and in acceptance, and I think the future is pretty bright. I'm optimistic about it. It may take a long time but it's on the road, I think.

Greg Dalton: Do you think that fundamental technology will change old need to happen? A big breakthrough in batteries or something that really changes the economics? Well, batteries are expensive.

Ed Whitacre: Yeah, batteries are really expensive.

I can't answer that question 'cause I'm not a physicist and some people -- physicists tell me you can't change chemistry, you know it is what it is. On the other hand, I think there's an effort, a lot of research on batteries, and I think we can only hope but I can't answer that question but I hope so.

Greg Dalton: For the first time for the last hundred years, petroleum has been the main source of fuel for transportation. Now, we have electricity. Some people want natural gas, biofuels -- there's now choices and competitions in the fuel marketplace, but there wasn't for the first hundred years of General Motors. How do you think that's going to affect personal mobility and cars?

Ed Whitacre: Well, I think petroleum is going to be the main source for some years to come. But I think solar, wind, electricity -- but electricity has to be generated by something, you know, natural gas or coal or oil. But I think we're slowly but surely moving in the direction of the things you're talking about.

Greg Dalton: The -- when Dan Akerson was here, he talked about of possible gasoline taxes as one way to address the externalities so that when we burn fossil fuels, we don't pay for the full consequences of the fossil fuels. Is that something you think that could be useful, a gasoline tax or would that be unwise?

Ed Whitacre: I have no comment on the gasoline tax. No comment, Greg. [laughter] I don't know, I haven't studied that. I don't know what the impact would be, I don't mean to be put offish but I just don't know.

Greg Dalton: How about in the recent years, the CAFÉ standards for auto miles have doubled? It's doubled, gone up to -- it's now going to be like 55 miles a gallon. That partly happened because the government was a large shareholder in General Motors had just rescued the industry.

They agreed to some pretty aggressive goals to double the fuel mileage in a pretty short period of time after they had been flat for almost 20 years.

Ed Whitacre: Right. Well, the CAFÉ standards of course apply to all makers. So it's not only GM. And I guess the question "is that doable?" and yes I think it is. I don't think anybody would have agreed to it. I'm no genius on that. In fact, I'm not well versed but I think and our engineers that we could do some of that. There are a lot of other questions related to that that I think maybe require some more consideration. Ethanol is an okay product. It's a good product. But ethanol and gasoline, your miles per gallon go down. It's not as near as efficient. And so I don't know if we're talking about standards with pure gasoline or gasoline with ethanol added, I don't know. To meet some of the standards that diesel engines for example have to have almost the equivalent of a chemical laboratory attached to it to meet the CAFÉ standards.

But overall -- and there was a lot of conversation you could have a tire or a set of automobile tires with less friction. But the problem is you can't stop. So you put on the brake you don't stop. So there are a lot of considerations in all that stuff, but I think the CAFÉ standards can be met and I think it probably will be.

Greg Dalton: And do you think that they're going to force innovation in the industry? Is that going to be -- because some automakers have been here and say, "We're not sure how we're going to meet those goals," but we have to come up with some pretty creative ways to do it..

Ed Whitacre: Well, I think we can do that and I think people have thought that through. I think there's -- there were transmissions or there were things that you can do to the motor. perhaps tires -- there's a lot of different ways to approach that. And you know, some of them have some drawbacks. But I think in general, we're going to reach those goals.

Greg Dalton: Do you think that you as manufacturer and U.S. companies can be competitive relative to Germans and Japanese?

Ed Whitacre: I've always thought we could be more than competitive. I think we can be, I'm sure we will be. I'm very optimistic about our ability to compete, and yes, I think we can do that.

Greg Dalton: The market share of General Motors hit 18 percent in 2012. At one point I think, more than half of the cars sold in the country were General Motors. That, according to an AP story, was perhaps the lowest share in history for General Motors would suggest that consumers are looking at other choices in the marketplace and buying Japanese, European, et cetera. Do you think that will come back? I mean that -- is that a competitive position?

Ed Whitacre: Well, I think the market share is an interesting thing to look at. First of all, we discontinued two lines, Oldsmobile and --

Greg Dalton: The smaller GM, uh-huh.

Ed Whitacre: So it's a smaller GM. Back when GM had half the market share, there weren't many competitors as I remember. There were cries for Ford and GM. Now there's a lot of worldwide competitors as you know who operate in this country.

So I don't know that market share is the question, although I personally think it will come higher. And you were right, it was over 50 percent at one time. But I think profitability and high-quality cars -- cars that satisfy the consumers should be the number one objective, and I think it will be.

Greg Dalton: And I've read that American car companies are actually selling fuel cars but because they shed some of their fixed cost, they're actually making more per car, is that right?

Ed Whitacre: Well, let's say GM in the first quarter made over a billion dollars a couple of years ago, so we were doing okay at making money, yeah.

Greg Dalton: Another company and country doing well at making money is China, and that has not been a -- they really haven't been a factor at least on imports on cars recently, but Buick exists today because of China. I think you're right that Buick is popular in China and that --

Ed Whitacre: Buick is very popular in China.

Greg Dalton: And it would have been perhaps discontinued if it weren't for the Chinese market?

Ed Whitacre: I don't think that's true but China's certainly a great market for Buick, and I took -- I took a great deal of pride in that it cost more to rent, lease, or buy a Buick in China than it did a Mercedes. It made me feel good. It was more popular. But it has done very well in China. But it's going to do well here, too.

Greg Dalton: China's last emperor was fond of Buick and that people remember that very well there. But how do you think China will play out? Will we see Chinese imports into the U.S. market? Will we China develop new technologies? Because they aren't really -- it's a domestic market. We haven't seen them on the global scale.

Ed Whitacre: You know, I can't answer that and I'm not close enough to it anymore. But I know a partner we had in China was a very good partner. And it was a 50/50 partnership. What happens in the future, I guess, entrepreneurs and business people will be business people. So I guess we'll just have to see.

Greg Dalton: If you're just joining us on the radio, our guest today at Climate One is Ed Whitacre, former chairman and CEO of AT&T and General Motors. I'm Greg Dalton.

Let's talk about the stock. Do you believe that the federal government should have sold the whole thing on day one? Tell us about that.

Ed Whitacre: Well, you know, General Motors, in rough terms, took $50 billion of your money and mine -- taxpayer money. And I believe that was the right thing to do. But I believe General Motors should pay all that back.

And when you borrow something, that was brought up to understand that you should pay it back and not forget it. Well, at the IPO time, the stock was over-subscribed. That meant there were more people that wanted to buy than was available to be bought. And it was also $33 and something a share. And had the government, at that time elected to sell more or produce more stock, it could have gotten a lot more money back for the taxpayer. There's still some to be paid back now, that was not our decision. That was the Treasury's decision for whatever reason they made that. I understand that, they sold so many shares, but they still own a reasonable person of GM which I believe GM has to pay you and I back -- the taxpayer, over time. And it's still several billion dollars. So I have to do that.

Greg Dalton: And that's a tough situation. Right now, General Motors' stock is about 20 percent below the IPO price, so you're right -- you'd say this gently but they should have sold on day one that the taxpayers would have been better off. Ford is also down about 2 percent since that time. Toyota in the S&P index are up about 20 percent since then.

But that's a tough position now to say, well, the taxpayers are leaving some money on the table.

Ed Whitacre: Somebody's got to figure that out, Greg. I'm not there, but I believe GM should pay back the taxpayer. It's selling for I think 28-29 bucks now, I've forgotten exactly. Anyway, it'd probably get 33 something a share. So you're right. It's down 20 percent. But there's away to figure that out.

Greg Dalton: Well, and what the Treasury plans to do is gradually sell over time dollar cost average out. So they're planning to get out, that's what they're currently --

Ed Whitacre: Well, they have sold some since I left, so it's a good sign.

Greg Dalton: Let's talk about the chairman and the roles of chairman and CEO. There's been some moves in companies recently that separate those roles for governance reasons. And you think that they -- that that's -- at least for GM, that's not the right move, that the same person should hold both of those roles.

Ed Whitacre: Yes, I think the chairman and president or whatever title you want to put on a chief operating should be one and the same person. I believe that that leads to a more functional organization. I think you can move quicker. I don't think you'll run into quite as much bureaucracy. I just think it works better.

Greg Dalton: And for all companies or certain types of companies?

Ed Whitacre: Well, I don't know about all companies. I thought at AT&T, it was best to have the chairman, president or whatever together. I thought that at GM -- I would probably think at about most companies, but I've not studied all of them, so I don't know.

Greg Dalton: How about -- you touched briefly on this CEO compensation. One of the reasons that GM was hobbled, because of government restrictions from pain, competitive market salaries to a new chief executive. And that was because of the bailout -- had those restrictions on it. So how did that affect GM's ability to recruit talent? And then I want to get to sort of the broader question of CEO compensation.

Ed Whitacre: That's a good question. GM was under what's known as TARP, the Troubled Asset protection or Relief Plan, which meant that the U.S. Treasury was the one who determined who got paid and how much at GM. Certainly I think you could say in the short term, all the high-paid executives pretty much left early on. I think you could say that over time, I don't think it hurt GM in the interim, in a few months. But over time, if you can't be competitive in the area of compensation, you're not going to do as well as your competitors.

Hopefully that will go away; I think it has slowly gone away. And I think all of us could see if you can't be competitive, you're not going to get the talent you need.

Greg Dalton: You write fondly about Steve Jobs in the book -- Fortune magazine a few years ago had a cover story with Steve Jobs and the headline was "The Great CEO Pay Heist." There's been a lot of talk about executive compensation getting beyond sort of the rank and file compensation. I wonder if you have any thoughts about that.

Ed Whitacre: Well, I do. You know, if you take more risk if you're responsible for the shareowners and providing good returns to them, and if you take more risk, you ought to be paid more. So then it becomes a question of how much more. I don't have the answer to that. I know -- when I see some CEO salaries, I say that's too much. And I know that just because I know it. And you probably feel that, too. [crosstalk] yeah, but I won' tell you. But put an absolute dollar or a number on it, I don't think you can do that. I think it's -- there's got to be some reasonable-ness, and -- put more risk, if you do better for the stockholders, you ought to be paid more. It's just a question of how much.

Greg Dalton: But does the system taking on risk in the short term to -- for a CEO who knows he's going to be in office for three or five years, they're kind of incentive to frontload some risks that might bring problems down the road for their successor, but they're gone -- they got their compensation and the shareholders take a hit later.

Ed Whitacre: That's true. And I can't argue with that. A CEO's major role is to perpetuate the company. And that's for a lot of reasons for employees, for customers, for stockholders, or whoever. But that's sort of the number one role.

And I don't disagree there's some who take a short-term view and make a lot of money and move on. And I guess that's one of the frailties of the system. But I don't know many like that.

Greg Dalton: The -- a lot of talk these days about too big to fail. You ran a company that was bailed out by the government. Do you have thoughts about -- you clearly said GM should've been rescued. Do you have thoughts about other companies in the future that should be bailed out? You know, Lehman Brothers was at the right thing, a lot of debate about that. So if -- down the road, when should the government come in and when should they let something fall even if it's painful?

Ed Whitacre: Can't answer that really for sure. I don't even know how I'll feel about it. I feel different day to day, and I think I could make a valid argument either way. Too big to fail -- I don't know. I can't see the consequences of some company that's large. I can see the other side of it, too. I can't -- I don't know how to answer that.

Greg Dalton: Hypothetical. Lot of characters in this story. Looking back, who do you think were the heroes in this story? Who were the villains and who were the victims?

Ed Whitacre: Well, the heroes certainly were the people at General Motors, and when I got there, they were embarrassed as you might have guessed. It'd gone bankrupt. Some of them were ridiculed by their neighbors. Their neighbors wouldn't speak to them, "you work for a bankrupt company."

So they were hungry to prove that they were as good as any workers in the world. So that was a big plus. And I found the people there to be terrific. I found once the organization was simplified, once we had an organization chart, once we assigned accountability, responsibility to employees and management people that things picked up. So I think the people at General Motors were clearly the heroes. Those that had to leave, they didn't feel so good about it.

Greg Dalton: And you employed a method of management by walking around, which I think was made famous -- I forget if it was David Packard or Walter Hewitt, but management by walking around was something you did. Going into the lunch room, showing up places where the executives have never showed up before. It's a very cloistered existence: separate elevators, parking garages for the rarefied air, for the executives at GM.

Ed Whitacre: Well, I believe that you should treat people like you like to be treated. And I believe we're all alike and that is we want to feel like we belong, that we have a part in what you're trying to accomplish, that we can do something good, we can feel successful, we can participate in it. And I think that needs to be conveyed. You know, people are the biggest asset of any company. If you don't have the people with you, you just don't make it.

You might make it for a few months, and I think that's true of any business. If you don't have the people with you, you're just not going to get there. And I enjoyed, I grew up in an environment where I was comfortable with workers, you know, everybody. And I guess I'm a social person. It's just the way I manage. I like to see who's doing everyday.

Greg Dalton: And the villains and victims in the GM story?

Ed Whitacre: Well, I think, I hate to put it in terms of villains. I think just in -- there was a mentality at General Motors that whatever we do is right, and if we change anything, it'll be wrong and therefore, we're doing it the right way. And they kind of rode that philosophy into bankruptcy. And the quality of the cars was probably not very good. The designs weren't very good, and you put your head in the sand over a period of years, you go bankrupt. You just go broke. I think that's all been turned around. I think GM has a terrific future. I think it has great people.

I think the villains were -- I believe management was responsible for everything in the company. Pretty much, the direction -- the action. So I guess I should have said past management responsible for that. I'm not sure you'd call them a villain but you'd say that they refused to adapt or change or to do something. They went bankrupt.

Greg Dalton: I'm not saying it is the villain either but there's Bill Ford, executive chairman of Ford Motor Company was here and he told an amazing story about how GM was on its knees and GM went to Ford and said, "Hey, let's merge." Ford was in a much stronger financial position, but GM thought that this kind of forced marriage, GM would still have the upper hand because, well, they were GM.

Ed Whitacre: That's the GM mentality. The old mentality. They'd do no wrong.

Greg Dalton: What was the biggest you faced in your time at GM? What was the hardest thing to do?

Ed Whitacre: I think the hardest thing to do was to convince the entire workforce that we were supposed to design, build and sell the world's best vehicles, get the right management team to do that, convey that to everybody and do it everyday, every hour of whatever it took to get the mental change so that everybody would see that in a short period of time, we could be profitable again instead of just kind of lumbering along like we have been. Get the right people in the right job is the key.

Greg Dalton: This is what's hard to get. Even after bankruptcy, they still thought they could kind of keep lumbering along.

Ed Whitacre: "We did nothing wrong. The economy got us."

Greg Dalton: How much --

Ed Whitacre: "We did nothing wrong. The economy got us."

Greg Dalton: How much of that do you think is because a lot of the senior people were lifers who didn't know anything else, they'd never worked anywhere else, and some of the executives had a real hard time making decisions about firing cousins or -- that it was so inbred and familial that they didn't see the outcome --

Ed Whitacre: Well, I think that was it. I don't think any of you could believe the bureaucracy that existed there. I just don't think you could understand how much bureaucracy was there. I mean you couldn't get anything done. Nothing. It's just that way and it was the GM way and you know, for whatever reason I guess it worked for a number of years, but it sure didn't work.

Greg Dalton: But AT&T is also a company and you're also on the board of Exxon-Mobil that -- a lot of these other companies where people spend their whole life and career, yet they don't get as insular as the auto companies did.

Ed Whitacre: Well, I think you'd have to say that's management, board of directors, the way you feel about things. I for one know that simpler is better. Simpler organizations, right people, right job. Stay focused on the things that need to be done. Forget the superfluous. You know, at GM if it didn't involve designing, building or selling the world's best vehicle, we didn't want it around. You kind of have to take that attitude.

Greg Dalton: At one point, they don't -- the satellite company -- okay.

Ed Whitacre: On a lot of things. And did great services for this country during the war. Built a lot of armaments. GM helped win the war. World War II did an incredible amount for this country.

Greg Dalton: We're talking with Ed Whitacre, former chairman and CEO of AT&T and General Motors. I'm Greg Dalton.

What would you do differently? What was one of the things that -- if you replayed the tape, what would you do differently at your time in GM?

Ed Whitacre: Well, one of the things I might think about -- I had a real dilemma there because I was -- I didn't think I was old but the calendar said I was pretty old. And I didn't know how long to stay, and I loved the job and I loved the people and it was a lot of hard work. And we got profitable much quicker than anybody thought.

And I had gone to Detroit with the intention of staying through the IPO which everybody thought would be two or three years. And then I'd go back to San Antonio. Well, we did swell that we were ready for an IPO in nine months. It was time to do that and become a public company again. I was really torn about leaving so early, but I decided that whoever replaced me needed a longer runway rather than me sticking around for another few months or a year or so. Somebody needed a longer runway, and Dan's younger than I. He could stay longer or whoever was picked. I might rethink all that. I don't know.

Greg Dalton: So you might have stayed. And one last question, we're going to bring a microphone out.

Ed Whitacre: That's just one thing but there's more.

Greg Dalton: So you've -- you might have stayed?

Ed Whitacre: Well, I think I've always been concerned. I don't know if I would or not. But you know, it's always bothered me that I had to leave relatively early. On the other hand, we were making a lot of money. You could see that the momentum was building in the company. You could see its future is going to be pretty bright. And so that's one thing.

Two, I would have changed a lot of things, Greg. But, you know --

Greg Dalton: And Dan Akerson was not your choice. You wanted Mark Reuss to be the next CEO -- that didn't work out. Tell us about --

Ed Whitacre: Well, that's -- well, let me explain that. Mark Reuss was a talented young executive in GM and he was a what a call a car guy. He understood cars, I didn't. I don't think Dan's really well versed in cars, either. He probably is now, but we weren't at that time. And if we were looking for a car guy, our internal candidate, he would have been my choice at that point in time. I've always felt that internal candidates are better than external candidates for most businesses.

I believe if you promote from within, most of the time you're better off, because they have a passion for the business, they know the people, they know the product and so -- that's just a general feeling I have. But Mark was, as an insider, the one. I think Dan has done a terrific job. I think GM continues to have good designs, bring new products out, and make quality stuff. I think GM's building the best cars in the world.

Greg Dalton: We're going to invite your participation now if you'd like to present a question. The line will form here and with our producer, Jane Ann, invite you to join us with one one-part question or comment. And I'll help you keep it brief. So now, let's go to our audience questions for Ed Whitacre, former chairman of General Motors.

Male Audience: It's a pleasure to listen to you, Mr. Whitacre. You have indicated in your talk that you believe in the tremendous future for like of American manufacturing sector, you believe in the country. Yet at the same time, one of the great companies in the country's history almost collapsed. Is there other such things happening in other board rooms around this country where incredible companies are -- how is that not going to happen again? How are you going to make companies of the future -- of the present and of the future, incredible so that they can actually do what you said?

Ed Whitacre: Well --

Greg Dalton: That's a big job, Ed. How are you going to do that?

Ed Whitacre: That's a big job. [laughter] You know, I have great faith in the American workers and American ingenuity. And I understand what you're talking about it's a complicated question, but I think we can be competitive and I think we can be competitive with ingenuity, with a lot of different ways. I think we have to figure a lot of that out.

But I think General Motors could be as an example, or AT&T competitive with anybody in the world. And sort of what goes around comes around, I think we have the ability to that. I can't tell you specifically everything that will happen. But I think the American worker is better than any in the world now, and I think they have access to more technology. I think we have ingenuity. I think we have drive, will, ambition. And I think we'll figure all that up. I guess it boils down to I just believe we can do that.

Greg Dalton: Let's have our next question for Ed Whitacre.

Male Audience: Hi, Ed. You mentioned ethanol in your talk. I'm sure you know the reason that ethanol is just poor in mileage is because you're putting it into an engine optimized for gasoline. If you reverse the procedure and optimized the engine for ethanol, ethanol gets better mileage than gasoline. Ethanol has perhaps --

Ed Whitacre: I think I'm in trouble here. He knows what he's talking about.

Male Audience: Well, no. That's the case. And ethanol has maybe 1/20th or 1/50th of carbon imprint of gasoline.

Ed Whitacre: Well, I know that. I'm aware of it.

Male Audience: And the ethanol engine optimized for ethanol costs maybe $100 more to make them a gasoline engine.

Ed Whitacre: Agreed.

Male Audience: As a consumer, I want to be able to buy an engine that's optimized for ethanol. Why can't I do that?

Ed Whitacre: Well, I think some of the engines are being optimized over time and you're right, it's a relatively -- as I understand it, a relatively inexpensive process. And I think that's -- looks like to me that's going to happen over time. I don't think there's much doubt about it. So I understand outboard motors same way -- all engines the same way. I can't answer your question and you know more about it than me. I said I wasn't a car guy. [laughter] But you know, obviously it's going to go that way because it's cleaner, et cetera, et cetera.

You make a very good point that I really can't speak to.

Greg Dalton: Let's have our next question for Ed Whitacre.

Male Audience: Thank you for speaking with us…

Ed Whitacre: Maybe we can find some other than corn to make it out of, too, right?

Greg Dalton: That's right, yeah.

Ed Whitacre: That'd be helpful.

Male Audience: I see why they made you CEO of General Motors…

Ed Whitacre: I'm what?

Male Audience: I see why they made you CEO of General Motors.

Ed Whitacre: Which is?

Male Audience: I mean you're trying to set the right idea.

Greg Dalton: Let's have our next question for Ed Whitacre.

Male Audience: I don't have that much craze. You talked a little bit about battery technology with Chevy Volt and the promise of battery technology, and we've seen how important batteries are, not just within cars and automobiles but within cellphones, within electronics. Now, we're seeing the importance of battery technology with airplanes, that instance that Boeing has had recently. And the question I had is should the federal government be stepping up in investing more battery technology? We've seen some of the politicizing of federal government infusion of money into energy and renewable energy projects, looking at A123 and other projects. Should the federal government be doing more? And what will it take to get better batteries 10, 20, 30 years from now?

Ed Whitacre: In my very limited understanding, it's a matter of basic physics and the potential between two materials governs what's going to happen in a battery. Whether that can change through laws of physics or not, I don't know. Should the government be more involved? I guess that depends on your philosophy. We've historically depended on private industry to do that. Capitalism with a motive. I don't know, but I know there's a tremendous amount of work going on in batteries in the car companies, in entrepreneurs, in other locations.

Should the government do it? I guess that's a matter of your philosophy. My philosophy would say no. It shouldn't.

Greg Dalton: So -- just a follow-up there. I mean you ran AT&T, which obviously is a data company as much as a voice company. These days, with Internet being a big part of that, the government, particularly the Department of Defense, played a big role in starting the Internet in the early days. Do you think that was a proper role of government?

Ed Whitacre: Well, I think everybody including the Vice-President took credit for the Internet, didn't he?

Greg Dalton: Yeah. Yeah. But in this case, the DOD, it really was the Defense Department that did it.

Ed Whitacre: Well, that's partially true. But you know, that's a defense thing. I'm not saying that's good or bad. They did play a big role in it. They also control a lot of the spectrum, as you know. And to -- handling increasing amounts of data, we need more and more spectrum. And that's got to be figured out, too. I'm not saying it's a bad or good thing. Just saying it was my personal belief.

Greg Dalton: Let's have our next question for Ed Whitacre.

Male Audience: Ah, yes. Since 1955 when I bought my '38 Oldsmobile for $50, I've always had American cars -- for years. I went out -- the last remaining car company in San Francisco was a Ford, sold about three -- two and a half years ago, I bought myself the Mustang every kid wanted. And a little in about a year, they moved out of the city, closed it, and now they're about 20 miles down the road --

Greg Dalton: So you're asking a GM why Ford moved? Can we --

Male Audience: Yeah. Well, I'm just saying that there's no domestic cars. So the question I have is why cannot there be a domestic car company in San Francisco, a thriving, affluent city, and especially with your Volt? With all these greenings running around.

Ed Whitacre: You mean a dealer where you buy one? That's what you're talking about?

Greg Dalton: Right.

Ed Whitacre: Well, I think all the dealers that I know, and I know quite a few of them, moved where the population moves. And I know in San Antonio where we live, the Cadillac dealer announced yesterday he's moving out north of the city because that's where the action is, there are more people out there, and therefore there's not going to be one downtown. You know, they're like a franchisee. They're like McDonald's, you can't pick where they want to go. They're trying to maximize their sales potential. And downtown is not it for most of them. At least that's what it says in some -- so they're all moving out to where the people are commute.

Greg Dalton: There's another piece of that, which is what is America in these days when GMs or Fords are made in Mexico and Canada, Nissan's made in Tennessee, and BMW is Alabama --

Ed Whitacre: It's a global economy, we're all dealing with that. That's just what it is.

Greg Dalton: Let's have our next question.

Male Audience: Good evening. My question is what made you the perfect fit for the job? And if I may have another question, do you -- did you understand?

Greg Dalton: What makes you the perfect -- what made you the perfect fit for the job?

Ed Whitacre: I wasn't the perfect fit for the job. There are probably people more qualified than me. As I said, there are only two things that qualified me. Maybe it was that I ran a large company for a long time and I dealt with unions a long time and organizations and things like that. But in terms of car knowledge, I was obviously not the right choice. But we did okay and I -- maybe we proved you don't have to be a car genius to run a car company.

Greg Dalton: Well, I mean Al Mulally, who you was -- came from Boeing to Ford, was not a car guy and he helped Ford get back on track.

Ed Whitacre: Right. Yeah.

Greg Dalton: So there is a line of view that --

Ed Whitacre: But I wasn't the perfect choice.

Greg Dalton: Yes, welcome.

Male Audience: Native of Michigan. My first car, a '51 Chevy when I was --

Ed Whitacre: Me, too. That's exactly what my first car was.

Male Audience: I was in the Army at that time and across the country three times. One reads a lot about the problems of the city of Detroit, how is GM interacting with the city, and what do you feel the responsibilities are for a company and employer in a metropolitan area in which it resides?

Ed Whitacre: I think that's a thoughtful question. General Motors, when I got there, had plans to move out of downtown Detroit and go to Warren -- move out to Warren, which is 20, 30 miles out northwest. And I stopped that. One of the first things I did was stop that moved for two reasons: one, it was going to cost millions of dollars to move out of Detroit. We had the space in downtown Detroit. And secondly, really when you think about it, GM's the only business in Detroit. You have to go there but there are no grocery stores, no drycleaners. There's nothing like that anymore, and I thought we'd be better served, and Detroit would be better served and we were, I guess the only taxpayer there. So we decided to stay there.

The interactions with Detroit were good. I hope they stay that way. The Renaissance is a big building in downtown Detroit, and Detroit as you know has got a lot of challenges, but I know GM's going to be part of that going forward and see what happens. Hopefully, it will improve.

Greg Dalton: And on move, you're speaking of someone -- you did move a company once for - out of Missouri to Texas --

Ed Whitacre: I did.

Greg Dalton: -- and that can be a very disruptive process and you write that when AT&T moved, that was [crosstalk] a very sad day.

Ed Whitacre: Yeah, it was a very sad day. The saddest day.

Greg Dalton: Let's have our next.

Male Audience: You did in your talk mention something about the bureaucracy. General Motors, probably at one point, had budgets as such that exceeding some countries in the world.

Ed Whitacre: You guys speak at the mic.

Male Audience: You talked about the bureaucracy, and I'm saying that General Motors at one point in time, at least had budgets in excess of certain countries in the world have. What would your take of it be as to these large, huge organizations and bureaucracy, which sometimes sounded deaf now of many entities. After your experience at General Motors? What did you gain from that and what would you have to espouse through others about the bureaucracy issue?

Ed Whitacre: Well, I think bureaucracy develops when people don't have enough to do. I think when they're not involved in the end product and they want to feel important, and they want to feel like they've contributed to the end product, and management doesn't provide that for them. Then I think they'll get busy making themselves feel important by putting in a new rule, a new law, a new standard, a new something, and that equals bureaucracy right away. And I think that happens when you don't involve your people, they don't feel needed, they don't feel important, they don't feel like they're contributing to the end product. To make themselves feel good, and you and I are the same way. We'll invent something so we do feel important. Most people will. And that equals bureaucracy -- that is bureaucracy. We need another test on this, we need to examine this. This needs to be under the microscope. This needs to go to somebody for review. We need a consultant to do this.

And all of a sudden, if you have people you don't feel needed or wanted and have no desire to contribute to the end product, you've bureaucracy. I'm not saying AT&T didn't have any bureaucracy; it did. GM had tons of bureaucracy. And I think it builds up when people want to feel important. And you put them in a position where they can put in something else and all of a sudden, you've got a bureaucracy that can't be penetrated.

Greg Dalton: But you also write about not being focused totally on numbers, the Six Sigma thing which is popular in some circles of corporate America. That's not the right way to measure and manage, either?

Ed Whitacre: Well, Six Sigma, in my judgment, management doesn't put any skin in the game or they don't have much to risk. Six Sigma, the objectives are sort of set by the management, then the employees are given these objectives and if they don't meet them, the top ten percent get fired -- I mean bottom 10 percent get fired. Well, I think that puts the owners on the employees and not management. I think management gets a free walk pretty much with Six Sigma. That's my only quarrel with -- it's been very successful for some people.

Greg Dalton: As we wrap up here, you mentioned climate change earlier. How serious do you think climate change is and what should we do about it?

Ed Whitacre: Well, I don't know. I'm from San Antonio. It hasn't rained this year. It didn't rain much last year and it didn't rain much the year before and we're in a drought. And whether that's a cycle or a cyclical, I don't know but we sure need the rain -- I understand it rained a lot out here earlier. I think climate is very serious. I think it's just common sense and I think that's what it is. If you're doing things to the planet, you shouldn't be, it's going to have a consequence. I can't go much deeper than that, but it just seems like common sense. I think it is.

Greg Dalton: So we're doing things we shouldn't be -- how should we change that? How do we correct that as we wrap up here and think about --

Ed Whitacre: Well, I think the things that we all think about, you know, less emissions, more care for the things, conservation of water, I mean you can go on and on and on.

Greg Dalton: Is that going to hurt business?

Ed Whitacre: Well, it has the potential to. I think good management focused on that can probably help that situation a lot. I'm a great believer that good management can do a lot of good in a lot of areas.

Greg Dalton: We have to end it there. Our thanks to Ed Whitacre, former chairman and CEO of AT&T and General Motors. I'm Greg Dalton. Thank you all for coming.

Ed Whitacre: Thank you, Greg.

[Applause]