Climate Stories We Tell Ourselves

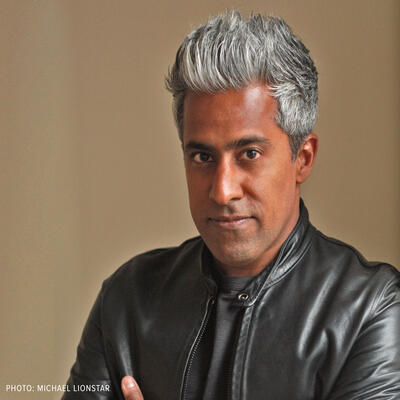

Guests

Nathaniel Rich

Meera Subramanian

Summary

Journalist Meera Subramanian has spent years talking with some of the people living closest to climate change in parts of the country where climate science isn’t always trusted. Part of the problem, she says, is the lack of conversation between the two sides of the national debate.

“Both sides are not listening to each other. I think it’s really easy for people on the climate activist side to completely and utterly dismiss the people who are skeptical, and vice versa. So I think going in and trying to understand what is driving somebody, what are they thinking about in the middle of the night?” she says.

In 2017 she launched a reporting project with Inside Climate News to seek out the most conservative communities directly experiencing climate impacts. Those stories ran the gamut as she talked to everyone from Montana flyfishermen to North Dakota ranchers to Georgia peach farmers and Texas Gulf fisherman.

“Everybody was seeing that there were changes [to the climate],” she says, “it was how people were explaining what they were seeing and what they thought should be done about it, which is where the friction comes from.”

Submaranian says opportunities for connecting across the climate divide exist in the power of listening and understanding how our identities and values shape the way we understand others’ climate experience.

“I think we've all gotten really used to telling our stories, putting them out there in the world, and it sometimes feels like maybe not so many people are actually listening to them,” she says. “And so I think sometimes showing up as a journalist and just being all ears can feel kind of profound.”

Nathaniel Rich is author of the new book Second Nature: Scenes from a World Remade. The book explores how humans struggle to maintain optimism when confronted by the effects of our impact on the environment.

“How do we understand a natural disaster if it’s not a fire at our door or water rising in our driveway? What’s the psychological ramifications of this?” he asks.

One of the stories in his book is about a massive methane gas leak in a wealthy Los Angeles suburb. When the leak was discovered, Rich says, the differing levels of concern among residents about possible health impacts nearly tore the community apart.

“The one thing nobody was really concerned about in the whole community was the effect on climate change,” he says.

Rich also discusses the role writers play in capturing people’s emotional responses to climate disruption.

“I think writers should be asking, ‘what do we make of the fact that we’re living in this moment, in this age, where we have this enormous dread of the future, [and] so much is at stake? How does our knowledge of this oncoming catastrophe or this ongoing catastrophe touch our lives today?’ And I think there's a job of writers in every age to try to understand the ways in which the public crises of the moment and the threats touched the inner lives, the private lives of the people who are living today.”

Related Links:

Finding Middle Ground, Inside Climate News

Second Nature, Scenes from a World Remade

Have you ever had a difficult conversation about climate? A disagreement, perhaps, or coming to terms with a new reality? We’d like to hear your stories. Please call (650) 382-3869 and leave us a voicemail about your toughest climate conversation. Or drop us a line at climateone@gmail.com. We may use your story in an upcoming episode.

Full Transcript

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. Talking about climate sometimes feels difficult, even as more people are directly feeling the impacts.

Meera Subramanian: We’re not listening to each other at all, and we’re not listening to what each other is listening to, either, with the media silo-ization that’s happened, right?

Greg Dalton: Journalist Meera Subramanian has spent years talking with some of the people living closest to climate change [pause] in parts of the country where climate science isn’t always trusted. Part of the problem, she says, is the lack of conversation among people who don’t agree.

Meera Subramanian: Both sides are not listening to each other. I think it’s really easy for people on the climate activist side to completely and utterly dismiss the people who are skeptical, and vice versa. So I think going in and trying to understand what is driving somebody, what are they thinking about in the middle of the night?

Greg Dalton: Climate One’s empowering conversations explore all aspects of the climate emergency On today’s show, we’ll talk with Subramanian about the importance of listening [pause] and how our identities and values shape the way we understand others’ climate experience. And we’ll explore the stories we tell ourselves to cope with climate disruption and other human impacts on the environment.

Nathaniel Rich: How do we understand a natural disaster if it’s not a fire at our door or water rising in our driveway? What’s the psychological ramifications of this?

Greg Dalton: Nathaniel Rich is author of the new book Second Nature: Scenes from a World Remade. He explores how humans have fundamentally changed the planet, and how we struggle to define our place on it and maintain optimism amid grim headlines and personal experiences. Rich says the values that were at play during the early history of nature conservation –

Nathaniel Rich: Fairness, a sense of restraint, a sense of a long-term thinking, and a sense of appreciating our blessings.

Greg Dalton: – he says that’s a valuable mindset to hold onto as we explore radical ideas and technologies like geo-engineering and de-extinction intended to correct impact on the world around us.

Nathaniel Rich: We should be guided by not just you know how do we improve things. How do we avoid the worst of climate change or any other environmental, you know, scourge? But how do we make the world truer to our highest ideals.

Greg Dalton: Today my guests are two journalists who explore how climate disruption, human failings and environmental realities affect people across the country. Meera Subramanian has spent years talking with people experiencing climate change, in parts of the country where climate science isn’t always trusted or understood. Part of the problem, she says, is the lack of conversation between people who don’t agree.

Meera Subramanian: Both sides are not listening to each other. I think it’s really easy for people on the climate activist side to completely and utterly dismiss the people who are skeptical, and vice versa. So I think going in and trying to understand what is driving somebody, what are they thinking about in the middle of the night?

Greg Dalton: We’ll hear more from Meera Subramanian later in the show.

Greg Dalton: Nathaniel Rich is author of the new book Second Nature: Scenes from a World Remade. His book explores how humans have fundamentally changed the planet, and how we struggle to define our place on it amid grim headlines and personal experiences. Rich says the values that were at play during the early history of nature conservation.

Nathaniel Rich: Fairness, a sense of restraint, a sense of a long-term thinking, and a sense of appreciating our blessings.

Greg Dalton: --he says that’s a valuable mindset to hold onto in our modern view of conservation as we explore radical technologies like geo-engineering and de-extinction intended to correct our impact on the world around us.

Nathaniel Rich: We should be guided by not just you know how do we improve things. How do we avoid the worst of climate change or any other environmental, you know, scourge? But how do we make the world truer to our highest ideals.

Greg Dalton: Harvard biologist, E.O. Wilson proposed setting aside half of the earth for conservation. And that in turn spawned a global effort to protect 30% of land by 2030. Pres. Biden supports that effort California is trying to do it. What do you think of those efforts to set aside X percent will that change human relationship with nature?

Nathaniel Rich: I think it's a great goal to have, I think I would love if we could achieve that. I do think it’s important to recognize, however, that already there's no such thing as a wilderness that hasn't already been altered dramatically by our presence. And even the act of putting aside nature he’s not really proposing that we necessarily just let it go. We’re now at a point where we also have to protect it and defend it against any number of possible you know issues. Climate change being just sort of one of them.

Greg Dalton: Nathaniel, in the book you write about Stephen Conley, an atmospheric scientist in California who has a freelance business flying over oil and gas fields measuring methane concentrations leaking out of them. One day in 2015 he was flying over Aliso Canyon in Southern California what did he discover?

Nathaniel Rich: Yeah, he had heard there was a gas leak coming from this gas facility in Porter Ranch, which is sort of North Los Angeles. And the numbers that he detected over this canyon and this beautiful sort of suburban type environment were catastrophic beyond anything he’d ever seen beyond you know what he'd seen going over you know places like the Bakken in North Dakota. And this was the beginning of a saga that is still going on many years later. Basically, what’s a leaking gas well ended up becoming one of the greatest climate disasters in history.

Greg Dalton: There was a litigation the company Southern California Gas settled with government agencies for about $130 million. I believe there is a class-action lawsuit representing 35,000 people that’s winding its way through the courts going on as you said. Porter Ranch is an affluent and somewhat conservative community nearby. What was the impact of this leak on residents and their attitudes toward fossil fuel?

Nathaniel Rich: Yeah, that was the most interesting part of it to me. The people in this community were mostly freaked out that they were getting poisoned by the gas. It was an old oil well that had been converted into a natural gas storage facility. So, the people in this very wealthy community, as you said pretty conservative, panicked and they saw it as their Chernobyl and they fled. And many reported health problems and many others did not. And it became this very strange sociological experiment as much as a chemistry experiment about how do people respond when they're told that there's a huge cloud of poisonous gas that they can't see in the community. You know, how do we understand a natural disaster if it's not fire at our door or if it's not water rising in our driveway. You know what's the psychological ramifications of this. And what I discovered is fascinating. Basically, it tells you it varies on, you know, depending on the person, but the way people responded tells you a lot about who they are. And the community in a certain way started tearing itself apart as a result. The one thing nobody was really concerned about in the whole community was the effect on climate change. You know, the proof of the health effects is still being litigated certainly and studied. But what we know is that the amount of methane that went into the atmosphere was gargantuan and of course you know with anything with climate change it’s cumulative. The amount of greenhouse gases we put in the atmosphere and the damage we do. But nobody in this community really thought about that aspect of it at all. It was all about how’s this immediately hurting me, my family or my property values.

Greg Dalton: Another person you write about is Robert Bilott who is a lawyer in Cincinnati. One day, a burly cattle rancher from West Virginia named Wilbur Tenet came to his office with boxes of videotapes, photographs and documents. What story unfolded from those boxes?

Nathaniel Rich: Yeah, it’s one of the craziest stories I've ever come across and it ended up being made into a really great movie that I recommend to your listeners called Dark Waters with Mark Ruffalo playing Bilott. He’s a corporate lawyer in Cincinnati and they basically represent chemical companies. They’re environmental lawyers for the defense. And Bilott who’s an up-and-coming guy himself fairly conservative guy gets this call from a cattle rancher who says that his cows are dying right and left and he thinks it's because they're drinking something poisonous from the creek that runs to the property. The creek runs from a site that’s owned by DuPont, which has this enormous chemical factory in this town of Parkersburg, West Virginia where they make things like Teflon and other things that we encounter in our every day in our lives. And he thinks that DuPont is up to something and nobody in town, nobody in Parkersburg will believe him. It's a corporate town everyone works for DuPont one way or another. And Bilott explains, you know, I'm not the right guy for the job. I defend chemical companies, you know, you want to press the losses against the world's biggest chemical company. But this cattle farmer makes a personal appeal. It turns out that he got Rob's number because Rob’s grandmother is friends with the cattle farmers neighbor. And so he has a soft spot for this community and he agreed to take the case, thinking that it will not do nothing. What it does end up amounting to is this saga that’s lasted now for more than 20 years has exposed one of the biggest corporate conspiracies in the world.

Greg Dalton: The chemical is PFOA, how prevalent is that today in humans and animals?

Nathaniel Rich: It’s in all of our bloodstream it's universal. It's been found in the blood of every living organism that's been tested for it. And it has been found in blood banks going back decades in studies done by DuPont itself and not made public at the time but discovered and exposed by Bilott. The main way I think we encountered it in the past was through nonstick cookware which you know we are of course told it was safe, always for decades. But in high heat it would leech off into the food and get in your bloodstream and the terrifying thing the most terrifying thing about this stuff this man-made chemicals is they’re bonded together to an extraordinary degree that there's sort of described as slippery, you know, anything that you want to be water resistant basically that DuPont made would have some element of PFOAs in it. And because of that it doesn't biodegrade. It doesn't go out of your blood. So, once it's in your body it stays there.

Greg Dalton: It’s part of a family called the forever chemicals.

Nathaniel Rich: Yeah, forever chemicals.

Greg Dalton: Right. And one of the parallels with climate that struck me when I was reading this was how there were scientists at the company there was even one meeting where scientists and lawyers said we got to stop this stuff. And the company knew and it violated its own rules about handling of the stuff there was internal dissent, we shouldn’t do this. Similar to scientists who raised warnings inside oil companies. So, there’s some real interesting parallels.

Nathaniel Rich: Yeah, it’s the same story over and over again. It’s the corporate playbook going back, you know, to Philip Morris and the tobacco industry as well. And it's truly shocking I mean Rob basically what he did is he forced DuPont to give him thousands really millions of pages of documents. And he put together this incredibly damning history going back to the 1950s of DuPont knowing the stuff was bad, knowing it was causing all kinds of health effects related to cancers, birth deformities, all kinds of terrible health conditions. And it continues to pump out the stuff because it was making more than $1 billion a year in profit on it. And so, you know, it’s a level of villainy that is, you know really goes beyond what you'd expect to find even in a comic book or something.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, that’s why made for such a great film. I tried to get my family to get rid of the Teflon pans for years, unsuccessfully. But as soon as my wife saw Dark Waters, those pans went in the garbage that night.

Nathaniel Rich: That happened to my own mother too. And I said, wait a minute, you know, I wrote the piece like you didn't -- when I wrote the story about it in the New York Times Magazine originally like and that didn't cause you to throw out the pans. But when Mark Ruffalo is throwing out the pans then finally you take it seriously. So, you know, whatever it takes.

Greg Dalton: She loves you but you’re not Mark Ruffalo.

Nathaniel Rich: Exactly, yeah.

Greg Dalton: One of the key players you also write about is Aspen, Colorado. And one of the key players there is Auden Schendler, an executive of the Aspen Ski Company. He compared climate change to civil rights and said Aspen could tell a story that catalyzes change as Selma did. And when I read that I was like, Aspen and Selma those are two very different places. Help us understand about how Aspen can be a vehicle or model for change and how that relates to us.

Nathaniel Rich: Well, it’s funny. I think he was onto something. I do think he was onto something there in comparing the climate, you know, fight for climate policy to a certain aspect of the civil rights struggle. You’ve seen a lot of the same tactics and language used for instance by the Sunrise Movement or the Green New Deal and they're making direct, you know, they’re also making more explicit that you know climate change affects us disproportionately that the people who are most harmed by it are those who are already the most harmed by our systems of governance and this sort of racist structures embedded in society and that you can’t address one without the other and so on. But yes, and it does strike a different court to say that Aspen Colorado could be Selma, but Schendler’s point was that we can lead the way essentially, and that we could we can show in Aspen, you know, the richest maybe, I don’t know, is it the richest place in the world? It feels like it.

Greg Dalton: It’s an enclave, certainly a lot of very wealthy people get there. So, but that theory of change is an elite-led theory of change which is different than civil rights, which was more grassroots. So, as someone whose, you know, you have studied individuals taking on powerful interest from the 70s to now, what do you think of that looking to elite individuals in places as leading the way off fossil fuels? Is that folly is that --

Nathaniel Rich: I don't think it has to be, it doesn't have to be in either or. I think certainly people who are in a position where they don't have to worry about any financial cost, they should be taking big swings at this thing. Is that sufficient? No. Of course not, is that --

Greg Dalton: But it's better to have them on your side? Yeah, it’s better to have them on your side than pushing against you. Which also happen at Aspen where one of the Koch Brothers was pushing at the other direction.

Nathaniel Rich: Yeah. One of the Koch Brothers who owns, you know, Bill owns a compound, build a compound right outside of Aspen that’s bigger than Aspen in his own Mountain Valley. He was opposing Schendler although much of that had to do with water rights. But, yeah, what Schendler’s point was that because they had so much money, they could really take ambitious measures. And he saw this his mission to convince the powers that be in Aspen to follow through on it. So, to move the town entirely off onto renewable energy. And, but yes, what was fascinating to me about the story was this kind of extreme hypocrisy of a place where most people fly in on their private jets and are CEOs of industries that are responsible for the brunt of our carbon emissions patting itself on the back and taking leadership of the problem. And yet, you know, there is something valuable, very valuable, though Schendler himself is doing and trying to convert these people to his way of thinking. So, those are stories that fascinate me some combination of you know just huge ambition and obsession and effort to try to solve a problem paired with colossal folly and hypocrisy. And this whole mix of problems and solutions. And the best example of it for me is that ultimately one of his great accomplishments is actually a partnership with Bill Koch’s coal plant where he convinced them to use the greenhouse gas emissions as a source of power. It’s the carbon capture idea.

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to a Climate One conversation about the climate stories we tell ourselves. I’ve been speaking with author Nathanial Rich. Coming up, he talks about the role of writers to capture the human condition amid climate disruption:

Nathaniel Rich: What do we make of the fact that we’re living in this moment, in this age, where we have this enormous dread of the future so much is at stake. How does our knowledge of this oncoming catastrophe or this ongoing catastrophe, touch our lives today?

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton, and we’re talking with two writers about the way identity, values and experience shape people’s own climate stories.

Nathaniel Rich is a journalist based in New Orleans and author of the new book Second Nature: Scenes from a World Remade. His book explores how humans have fundamentally changed the planet, and continue developing new technologies to stabilise it. I asked him where he thinks his writing fits in the larger climate conversation. He makes a distinction between what he calls “activist” writing, which pushes the reader to act, and what he does.

Nathanial Rich: I think there's also room for stories about some of these places where there is moral tension and there’s complexity as in Aspen, as in the Porter Ranch case. Where there's not necessarily a right and a wrong or whether some messy middle that emerges. And those are the kinds of stories that interest me. And I think because we've had such a horribly politicized conversation about climate, but also environmentalism for so long where you have one side having to fight so hard just to explain why it’s important to lower carbon emissions. That we haven't begun to have some of the more difficult conversations about ways in which we’re going to solve some of these problems. And that's ultimately where I think so much of the dramatic tension of the stories comes from are, you know, where it's not necessarily a good guy and a bad guy.

Greg Dalton: And you write about good guys in your previous book, Losing Earth. And it’s a sobering narrative about a forgotten moment when a small group of people risked their careers to speak truth to power about what you call are suicide pact with fossil fuels. And this is so painful because we've heard so many times, you’re writing about 1979 to 1989, which is so painful because we’ve heard so many times, we have a decade to turn the climate around. This is the defining decade, right, we’ve heard that again, you know, 10 years and yet you write about a 10-year period that could have been decisive. Does just that bum you out when you know that we had it?

Nathaniel Rich: Yeah, and they were saying that in 1979 too, you know, they’re saying we have about 10 years to figure it out. And I think they were right. I mean in order to keep you know CO2 levels where they were historically now, we’re talking about keeping CO2 levels to where we don't have just totally profound, you know, cataclysms. So, yeah, that to me was the most dramatic story about climate change that I could write because you know we know what happened from 1989 or so to the present, where we’ve had the emergence of this oil and gas lobby fighting tooth and nail any kind of climate policy the issue become politicized. And as a result, there’s been total paralysis basically on policy. But what's fascinating about the period between 1979 and 1989 is that there weren’t political coalitions for against climate policy. The oil and gas industry which understood the problem was doing nothing to try to help it also hadn't coordinated on an attack on any kind of meaningful change. In fact, there are people prominent people in the industry who publicly were saying, you know, something has to be done. And you had a small group of people in Washington, primarily policy people who for the first time understood the problem thought clearly and try to figure out a way to bring it to the attention of the public in the global public and try to get something done. And they actually came very close to what they saw as a solution, which was a global treaty to curb carbon emissions.

Greg Dalton: And one of the lessons from that period as you have said that patient rational argument has severe political limitations. Do you think a conversation on public radio and podcast as you are and I are having now is meaningful is this kind of rational, calm conversation delusional given the need for transformative change to save humanity's beacon life as we know it?

Nathaniel Rich: Well, I think it’s important to separate two different motivations. I mean is a podcast going to change the world? I'm sorry to say I don't think so or will a magazine article or a book probably. But there’s the activist question of how to get people to move on this how do we get politicians to move on that. But I think there's another question that I think writers should be asking which is what do we make of the fact that we’re living in this moment in this age where we have this enormous dread of the future so much is at stake. How does our knowledge of this oncoming catastrophe or this ongoing catastrophe, touch our lives today? And I think there's a job of writers in every age to try to understand the ways in which the public crises of the moment and the threats touched the inner lives the private lives of the people who are living today. And that's a very different you know that's not trying to negotiate the new treaty. But these are still very big questions and worthy of scrutiny.

Greg Dalton: And help us describe and understand. What can narrative literature accomplish that other forms of writing and journalism can’t? You think that there's some willpower and liberty and narrative literature.

Nathaniel Rich: I do and I think that's why I've chosen the narrative form to write about these things. I think through narrative writing to storytelling with characters whether fictional or nonfictional where you can go deep into the inner lives of the characters, you’re able to ask some of these deeper questions. It's really only through narrative that you can get into these questions of how do these great public crises enter into the fabric of our reality. And that is -- I was struck I think I’ve been struck over the years and this is why I ended up writing these books that really very few writers have written about climate change or some of these environmental global environmental issues through narrative. You have first-person journalism which could be a kind of narrative which is like reporter goes to place describes what she sees and writes about it.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, and Elizabeth Kolbert has done that. The first climate book I read was Field Notes from a Catastrophe. You’re right, they’re issue books, right, they’re not a lot of characters, right?

Nathaniel Rich: Right.

Greg Dalton: The climate it’s such a big thing that it doesn't have a lot of, yeah, memorable standout characters, heroes and villains. It's not --

Nathaniel Rich: And it doesn't have to be you know superheroes and super villains. I think what’s more valuable is the way ordinary people. How is this change the fabric of our lives? I would say it’s transformed it especially for younger people that we now see the world through this lens of disaster and dread to some extent. I mean I can't tell you how many people when I was doing the tour for Losing Earth came up after events and said, I'm so upset about climate change that I don't want to have children or I'm afraid to have children. I don't think it’s morally justified to have children. That to me was sort of the that issue is kind of the wedge into this deeper anxiety and fear that we've experiencing.

Greg Dalton: NASA recently reported that 2020 tied with 2016 as the warmest year on earth. You tweeted that news and said last year was likely the coolest year of the rest of our lives. What is that mean to you personally and, you know, I don’t know if you have a family or plan to have a family. How does that affect you?

Nathaniel Rich: Yeah, that was a little sunny, note of sunny optimism for me. Yeah, I have, as I was writing Losing Earth, I had my first son. My wife and I had our first child and as I’m writing Second Nature, I had my second. So, yes this is very, very much something that I think about and I think like anybody else-- I mean add to that the fact that I own property in New Orleans which is one of the most threatened by climate change in the world. And and sometimes I freak out about it sometimes I sort of don't think about it. And I think like most of us I go between the polls I make calculated decisions. I'm probably the victim of my own optimism at times. But that’s exactly what I want to write about. Try to understand why, you know, how do we go on how did someone like me who’s pretty well acquainted with the dangers of living in a city like New Orleans in our climate age why do I choose to live here. Well, there's a lot, you know, that has a long explanation, but that kind of that sort of the story of our time and that's what I want to write about in these stories.

Greg Dalton: We all have contradictions and nuances. That's what makes us human and interesting. Nathaniel Rich, is author of Second Nature: Scenes from a World Remade. He also wrote Losing Earth which depicts the period from 1979 to ‘89 in which Republicans and Democrats accepted fundamental climate science and sought to act upon it. Nathaniel Rich, thanks for coming on Climate One. I really appreciate your writing and your work.

Nathaniel Rich: Thanks so much for having me. I really enjoyed the conversation.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. Today I’m talking with two noted writers about identity and values tied to the stories we tell ourselves about climate disruption.

Meera Subramanian is a journalist covering culture and the environment. She’s written for publications including the New York Times, Nature, Orion, and Inside Climate News. I asked her how she writes about boundaries and identity when she covers climate.

Meera Subramanian: Mainly by going in and listening to people, I think that everybody has an identity, politics has now dominated life in America today, and so I think that comes from a place of something stronger, where people really do have strong identities to their place, which is something that I like to focus on a lot and to their communities, to their people that they care about, and a lot of times I think that a lot of the boundaries and the friction that we're experiencing now are just where there seems like there's clashing, but their often is actually ways that we could be finding more overlap there.

Greg Dalton: So we're not listening to each other.

Meera Subramanian: We're not listening to each other all, and we're not listening to each other what each other is listening to either with the media silo-ization that's happened. Right.

Greg Dalton: Right, right. So how do you get people to listen to you? And how do you listen to them?

Meera Subramanian: So much of what has been explored around talking about climate change is that people aren't listening to why people either care about it deeply, are very much against it and don't wanna believe that it's happening or are in the place in between, which is where many Americans are where they're just busy doing other things or they feel intimidated by the science, there's just so many reasons why people might be resistant or engaged or dismissive to use the six Americans idea that comes out of George Mason, that there are these six Americans. And I think that's a fair accurate representation, and when I've been out reporting, sometimes I'm seeking out people that are on certain sides of the spectrum, but what I often find is that both sides are not listening to each other. I think it's really easy for people in the climate activist side to completely and utterly dismiss the people who are skeptical and vice versa, and so I think going in and trying to understand what is driving somebody, what are they thinking about in the middle of the night, 'cause everybody's kind of up in the middle of the night, I think, especially these days. So what are those driving concerns, what are they worried about? And I think that is where the opportunity is, is that there are so many places where addressing climate change can address those midnight worries for everybody, no matter which of the six Americans you are, and that sometimes means that you have to let go of going back to identity and letting go of your own story about why a topic concerns you and listening to what somebody is saying about why it might concern them.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, there's sort of this immediate kind of rebuttal, they're sort of... I find this like, Oh, I bounce on each other what people say and rebut without really absorbing or reflecting, and it's often a lot of fear, I think underneath…

Meera Subramanian: Right, and what happens with that? I mean, psychologist tell us when we all know, we all get our defenses up when we feel attacked, just... It's just a human response. And so we have to hold ideas and facts accountable, there has to be accountability around what is actually happening on the scientific level, but just beating people over the head with that is not the way that...that narrative changes.

Greg Dalton: Right? So many... You have your fact, I have my fact, we can go counteract, counter fact. Back and forth. And that doesn't go anywhere. You just don't go anywhere. You traveled across the US in 2017, seeking out the most conservative communities directly experiencing climate impacts for Insight Climate News, you describe that project as a chance to leap over the political divide and find stories of people's lived lives, not to check the box, answer is a big data and algorithms that neglect hope fear and middle of the night dreams. So tell me more about that.

Meera Subramanian: Yeah, that it was a really amazing project. It was right after the 2016 election. I think people who have been working on climate for a long time had just come out of, I would say five, 10 years where the thinking was like, Oh, we just need to get more facts to people, people just don't understand the science, if we just get them more information. Surely everyone will be worried...

Greg Dalton: The Information Deficit Hypothesis.

Meera Subramanian:. And so that didn't work so well. And the more that the results of coming out of that 2016 election showed that actually action on climate was regressing and was definitely going to go really backwards under the Trump administration. So the question was like, How can we go out and listen to people and figure out what's going on? That was definitely a divide in the country that came out through the election, there was a growing divide within the news and the media landscape, which is definitely dominated by coastal entities that do not spend a lot of time in rural communities, in a lot of places where people where the vote went heavily for Trump.

Greg Dalton: What are some stand out people, what are some of the stories that people are telling themselves in the red America where they're feeling climate impacts. What's their story?

Meera Subramanian: Yeah, everybody was seeing that there were changes that just felt like it was unquestionable that people were seeing changes, it was here, how people were explaining what they were seeing and what they thought should be done about it, which is where the friction comes from.

Greg Dalton: The divergence is what do we do about it? Markets or government, that's where people kinda... I don't wanna recognize the problem 'cause I don't like the solution.

Meera Subramanian: Right, right. That came up a lot. I heard a lot about regulation over regulation.. Most of these stories led me to vary rural areas in Wisconsin and Georgia and West Virginia, Montana, and these are places... These are communities that are... I mean, to put it bluntly, these are communities that are often dying, the infrastructure is gone, the educated people have left because there's no jobs. I kept hearing about labor shortages. And these are people that are really, like I said, tied to their land, often their livelihood is tied to their land, so they are feeling the impacts first, it was really interesting sitting down with ranchers in North Dakota and saying, I'm here, coming from New England, where there's a lot of people upset about climate change, but arguably you're feeling the impacts a lot more than a lot of people that are hollering for action. But I also did find that the question about where people are getting their information really is percolating down across the board, I would hear talking points straight down from Fox News about, this has always happened, this is just a natural cycle, it'll get cold again. And I heard every little... It was kind of fun. Every little tiny counter-argument I would... Here, I would spend probably way to excessive amounts of time fact-checking, so when a Wisconsin dogsledder tells me, Well, it's because there's volcanoes under Antarctica that the ice is melting. That's why it's melting. And so I would spend time looking through the peer-reviewed studies and there are volcanoes under Antarctica, they are causing melting, but then that last step of connecting it to that, the scientists have figured that into their equations, they've figured out the solar cycles and solar flares and all of that, and that has all gone into the models that are telling us that we're warming now faster than we ever have before, and that it is the fingerprints of human burning of fossil fuels is the reason why we're seeing the warming that we are. Right, so that last part of the equation was gone, but these little kernels, these little tree data facts would get out and get amplified and people take them to heart.

Greg Dalton: You’re listening to Climate One. Meera Subramanian is a journalist whose reporting has taken her across the United States to discover how Americans perceive climate change in their own backyard. Coming up, she shares stories about the interconnectedness of climate and our air, water and food.

Subramanian: Everybody is starting to realize you cannot just tease apart one part of this equation and solve it. Because it is so inextricably linked to everything else. (:12)

Greg Dalton: That’s up next, when Climate One continues.

Greg Dalton: This is Climate One. I’m Greg Dalton. Today we’re exploring the climate stories we tell ourselves with journalists Nathanial Rich and Meera Subramanian.

Greg Dalton: In 2017 Subramanian traveled across the country for Inside Climate News seeking out the most conservative communities directly experiencing climate impacts. She related one story about Georgia peach farmers grappling with loss of their crop because winters didn’t get cold enough.

Meera Subramanian: The farmers that I met was the Dicky farm in Middle Georgia, they were seeing the changes, but they were saying, Oh, this could happen, it can get cold again, but at the same time, they were experimenting varieties that were more adapted to a warm climate and they are hedging their bets and they're figuring out if they can diversify. They were doing adaptation, they just don't wanna call it climate change, so there it was really about dancing around a term that has become so incredibly loaded, but they weren't adapting. At one point, I said, How many more failed years would you have to go through before you start really thinking about this differently? And he laughed and he said, Maybe one. And so he was one person who stuck with me, another person who really stuck with him, he was a fly fisherman in Montana, very conservative, pro-life and small businesses doesn't like regulations, but he was seeing the changes, he fly fishes every single day, he gets out on the water, he has a river right behind his house, he runs an outfitting Company, and he was seeing the changes he was... I opened that piece, talking about how basically fly fishermen are like... Are like climate scientists, they are constantly reading the environment around them, they're looking at what insects are hatching when... What they look like, what they can do to mimic the natural ecosystem so that they can get this fish that they wanna get, they're watching how the water is moving, that are watching the weather, they are paying attention to every aspect of their natural world, and they're in it and observing it so closely, and so he was noticing that insects were hatching a month earlier than they should have, and he was noticing that they were closing down the river has these beautiful blue ribbon Montana fly fishing rivers that they were being closed down more and more because the waters were getting too warm and it stresses out the fish to catch them and release them, which is what they do there, and they just have to basically shut down the fishing. So people who come from all over the world, all over the world, to stay at his lodge and go out fishing, they don't wanna get out there and find out that half the time they can't go out and fish 'cause it... 'cause the water is too warm, so these are just a... He had... And this, another interesting part about his story was that he was open to understanding about the impact of climate, and part of it was the idea of the trusted messenger, and this is an important part about climate communication as it's important about who people are hearing that climate cations an issue, it's important. Who they hear that from? So a neighbor of his, who we trusted, who was a geologist, was giving a talk on the geology of Montana, like the most politically neutral subject you could imagine, and in the middle of his slide presentation, he says, what we're seeing now is unprecedented, and the climate has always changed, but it has never changed at this rate before, and the only explanation is what humans are doing to the atmosphere, and he took that in, he trusted the Messenger, it was not being presented as anything political or loaded, it was just information, and he just continued to pursue that and educate himself in his own way, and he's now deeply concerned and he's working on trying to get the fly fishing people in the fly fishing community to really work on doing what they can to make sure that that this thing that they love to do can be done going into the future.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, trust that a messenger is so important. Meera Subramanian is a journalist covering culture in the environment, whose reporting has taken her across the US to discover how Americans perceive climate change in their own backyard. Your 2015 book, A River Runs again, explores how ordinary people in India are working to move the country forward for a more sustainable future. How did research in writing that book widen your own understanding of the global nature of climate challenges?

Meera Subramanian: Yeah, that was... I just saw all these dots connecting while I worked on that book, I was actually in my 20s, I did... I was doing environmental non-profit work, including living a lot of farm and teaching sustainable skills and growing organic food, and we were developing clean efficient wood cook TOS for use in the developing world, and so all of that were... They were basically the same topics that I ended up focusing the book on, which the book is framed around the five elements or fire, water, air and ether, and then for each element, I chose one story of an issue that Indians were facing and how they were facing it... So the Earth story was about the rise of organic agriculture in response to the Green Revolution and water restoration efforts, and so different to different stories that I would dive deep in each one, and so these were topics that I had do studying for 20 years by the time I had gotten out and done the reporting and so... But the changes that I was seeing were connecting to climate in such an important way that I think even if I wrote the book again now five years later, I would write it very differently, this is how much these dots are connecting constantly about... You can't care about one aspect of the environment without finding a climate change impact, so for issues around, say, you're concerned about birds, like bird conservation, you just like to bird-watch, there's a climate impact, you're concerned about food, agriculture is being impacted by climate. Water is being impacted by climate. Every single issue that you can think of around the environment and our natural resources, and the book is actually called elemental India in India, that has a different title there, and I was thinking about these as very elemental things that humans need... There's all these things that we want, and there's all these things that we enjoy, but there are these fundamental elemental things that we need, and their water and their air and their food, and they are very, very dependent on how we treat our natural environment and climate is affecting all of them.

Greg Dalton: Yeah, as well as the energy is embedded in everything that we do touch, eat every day, so there's... The causes are also in everything that the microphone, this chair, this computer, everything. It's mind body. 'cause it's everywhere.

Meera Subramanian: Yeah, and that was part of what I was addressing with the book because India is at a very interesting inflection point where I write a little bit about the... There was a huge, huge black out in India at one point, I think it was in 2011 or 12, 30 million people out of power, that's the population of the United States, just true. Million people out of power, but a vast majority of those people didn't even know they were out of power 'cause they'd never had power in the first place, so there's these huge India's growing powerhouse on the global... On the global stage. But there are huge numbers of people that didn't have access to clean water. Don't have access to energy. The Fire chapter is about clean cook stoves because most of India still at that point, 60% of people were using the open fires for at least part of their energy needs every single day. So the driving question of the book is, How do you get all the resources that can give those people access to the elemental needs that they need, how do you get them that without further degrading the natural environment that they live in? So how do you do that? How do you get those needs and the answers that you tap into renewable resources, whether that's education for girls or renewable energy sources from solar to drive an induction electric stove, that there's just...You have to tap into something that is gonna keep lasting, that is sustainable or not, it doesn't work.

Greg Dalton: Or indigenous cultures would say stop treating resources as things to be exploited and have more respect in a different relationship and even think of rivers as mothers and rivers and legs having rights, and so it changes the way that we think about these things that are to be exploited in service of humans.

Meera Subramanian: Right.

Greg Dalton: We've been talking in this episode about preserving our own idealistic and optimistic nature while coping with the loss and nostalgia of losing our environment to climate change, like you've just been talking about how do you see this tension play out in your own work or trying to be optimistic, but recognizing the loss around us...

Meera Subramanian: Yeah, that's something I sit with every single time I sit down to write. It is really challenging us as journalists, as a journalist who's on this beat, just in order to stay informed, it's kind of an avalanche of a lot of dire news on a pretty daily basis that said, you also come across all of the clear indications and reports and social scientists and technologists who tell us we basically have everything at our disposal to fix this problem now, and it's really just a matter of priority, so it can be a bit of whiplash going back and forth between the hope and despair of thinking about the climate at this point, but there is... There are a lot of indicators that we are really entering a new era, it's not just what's happening underneath the Biden administration is quite phenomenal, but I think the whole idea of... We're thinking about things a lot more holistically, and part of that is being forced upon people who maybe are not ready to be thinking about it holistically, but that is what's happening, the fact that we're connecting questions of environmental justice, of questions of who has access to what resources, and who pays the price for what those resources cost, the environment and communities, the fact that we're looking at having climate integrated into administration agencies across the Biden administration in a new way that has never been done before, the way that universities are having environmental programs that bring together economists and psychologists and social scientists, and that everybody is starting to realize that you cannot tease a part, one part of this, one part of this equation and just work on one problem and think that you can solve it because it is so inextricably linked to everything else, because that's how we... Humans live, we don't live in these separate bubbles, we are... Our professional lives or intertwined with our personalized... The pandemic has made that very clear. There's all these ways that I think for hundreds of years, we've spent a lot of energy and gain tremendous amounts of knowledge by breaking things down into their constituent parts and looking at them closely, but I feel like right now is the moment when we're realizing how much we've lost by not... By not helping keep those threads connected.

Greg Dalton: It's exciting to see the interconnectedness, it makes it kind of overwhelming to think about, What can I respond to? What can I affect of everything so connected and so big... People can feel like an ant so small that how can they affect these big interconnected systems, then we wanna bite off one piece and say, Okay, I can affect this, so that's how people get to straws.

Meera Subramanian: Yeah, yeah. And that's fine, 'cause if you feel better by not using straws, that's great, but then that's also... I think the thing that people forget is that we're also talented in our own strange quirky ways, we do the thing that we do, and we do it well, and then you ask us to do it something else and we're completely clueless, but... Whatever thing that you're good at, you know, just do that and do it in service to working on climate, and if that means talking, if that means being a stand-up comedian, if that just means making art, if it means organizing your community, if it means writing, if it means holding up in a cabin somewhere and thinking and coming out and merging with new thoughts, all of these can be directed towards climate action if you so choose, stopping at straws is the failure. 'cause there's just so much more that can be done, but I don't think that at this point, there are no wrong answers about how to be involved.

Greg Dalton: We need to do everything. So we kinda wrap this up, we've been talking about storytelling and the stories you've told by going to red states and peach farmers in Georgia. What I hear you saying is that the key to what I hear you saying is that you don't direct a lot of people, you come into conversations with curiosity rather than trying to steer or influence people, which is I think where a lot of climate concerned people are they go around trying to convert pressure, activate people to projecting their own anxiety onto other people, and what I hear you saying is you're curious... What are you observing? Actually, that's gonna present you as... I think that's gonna allow people to listen to you more, that their defenses aren't gonna go up when you're curious about them rather than telling them what they should think, which is the way a lot of climate conversations go.

Meera Subramanian: Right, right. Because there is, especially I think with social media and with the democratization of journalism and sharing stories, which is wonderful in so many ways, and problematic in other ways, but I think we've all gotten really used to telling our stories, putting them out there in the world, and it sometimes feels like maybe not so many people are actually listening to them. And so I think sometimes showing up as a journalist and just being all ears can feel kind of profound.

Greg Dalton: Meera Subramanian is a journalist covering culture in the environment who's reporting has taken her across the US to discover how Americans perceive climate change in their own backyards. Thanks for coming on Climate One. I really appreciate talking to you.

Meera Subramanian: Thanks so much for having me.

Greg Dalton: You’ve been listening to Climate One. We’ve been talking about the climate stories we tell ourselves -- and the need to listen to others -- with Meera Subramanian and Nathanial Rich.

Greg Dalton: To hear more Climate One conversations, subscribe to our podcast on Apple, Spotify or wherever you get your pods. Please help us get people talking more about climate by giving us a rating or review. It really does help advance the climate conversation.

Greg Dalton: Brad Marshland is our senior producer; Ariana Brocious is our producer and audio editor. Our audio engineer is Arnav Gupta. Director of Advancement is Steve Fox, Kelli Pennington, and Tyler Reed. Dr. Gloria Duffy is CEO of The Commonwealth Club of California, the nonprofit and nonpartisan forum where our program originates. I’m Greg Dalton.