Bracing for Impact: Bay Area Vulnerabilities and Preparedness

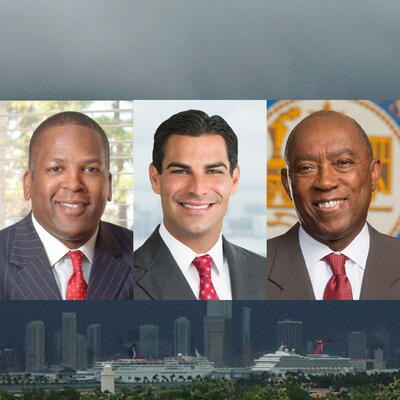

Guests

Ezra Rapport

R. Zack Wasserman

Melanie Nutter

Summary

"If we do not take the rational approach to this problem [of climate disruption] we are all facing really catastrophic impacts," said Ezra Rapport, Executive Director of the Association of Bay Area Governments. As the world warms Bay Area agencies are racing the clock to develop adaptation strategies to identify and manage risks. But with complicated and widely variable climate models it can be hard to agree on the numbers. Melanie Nutter, Director of the San Francisco Department of the Environment explained that “we as a city [San Francisco] don’t yet have an agreed upon risk scenario.” This is because “we are a very diverse region...there is no one dominant player,” said R. Zachary Wasserman, Chair of the Bay Conservation and Development Commission, “we’re going to have to figure out how to do this together.” Leaders of Bay Area agencies discuss strategies to protect our built environment and adapt to challenges in the future.

Full Transcript

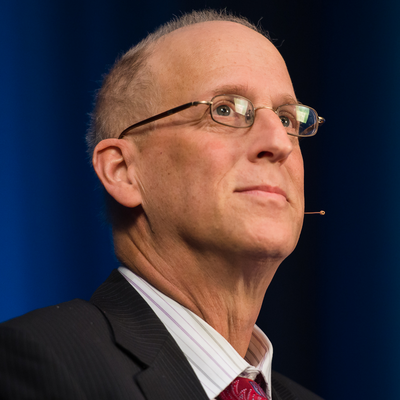

Greg Dalton: Welcome to Climate One, a conversation about America's energy, economy and environment. To understand any of them, you have to understand them all. I'm Greg Dalton.

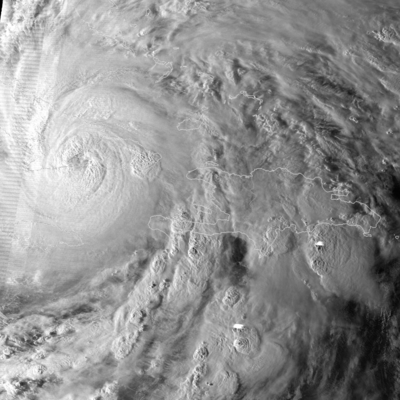

Many people alarmed about climate disruption thought America's coastal cities had a decade or two before they had to really get serious about the gradual threat of sea level rise, then came Hurricane Sandy. Seas are rising, warming and expanding combined with other factors to deliver an unprecedented knockout punch. California has an estimated $100 billion in property at risk from sea level rise, much of it in the Bay Area. Schools, homes, highways, hazardous waste facilities, power plants, the on-ramp to the fancy new bay bridge, are all at risk from floods in coming years.

Over the next hour, we'll discuss what a Sandy-like event might look like in the Bay Area and what is being done to prepare for such a catastrophe. With a live audience at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco, we're pleased to have with us three people responsible for helping to build resilient communities that could bounce back after a big hit. Melanie Nutter is Director of San Francisco Department of the Environment. Ezra Rapport is the Executive Director at the Association of Bay Area Governments and Zack Wasserman is chair of the Bay Conservation and Development Commission. Please welcome them to Climate One.

[Applause]

Greg Dalton: Welcome. Welcome all of you. Melanie Nutter, let's begin with you. When you were watching the television and seeing Hurricane Sandy bearing down on the East Coast, what did you think, and what did you think about if something like that would happen in the Bay Area?

Melanie Nutter: Frankly, it was terrifying. I mean, to watch what was happening in New York was really terrifying, and for many of us who are here on the west coast who have family and friends back east, hearing some of the stories about the lines that people had to wait in to get gas, the power outages, people who were trapped in their cars, where there was very severe flooding on the streets, it was really terrifying. So that was -- I mean, that was my reaction, I think similar to a lot of San Franciscans. And, of course, being somebody who works for local government, I also thought what do we need to do here in the Bay Area to ward off the worst effects of climate change. We don't want to see a Sandy in the Bay Area, but who knows if we will?

Greg Dalton: Well, that's a question. Some people think that while the East Coast, they get hurricanes, that can't happen. That's over there. It can't happen here. Any of that thought that like, "Well, that's New York. We don't have hurricanes. So, it won't be as bad here.

Melanie Nutter: So I think that there was some of that, but we also did have some severe weather events last year. It's a Pineapple Express that came to the Bay Area where we saw some rising tides and rising sea levels in the bay where, along our Embarcadero and along our port, you could see the impacts of a severe weather event in the Bay Area. So for anybody who was a naysayer, I think once we saw that, it really brought it home last year.

Greg Dalton: Zack Wasserman, I'd like to ask you the same thing. You saw Sandy, you're a chair of a commission that's responsible for governing the water's edge around the Bay Area, did you think, uh-oh -- what did you think when you saw Sandy?

Zack Wasserman: Well, I was certainly frightened, as was everybody else, and very concerned. But I will also say there was an element of not so much immediately, but in the aftermath, that was hopeful because Sandy is a wake-up call and the problem with adapting to rising sea level is it occurs over such a long period of time. It's not really here now for people. Sandy, to some extent, brought it home. I would certainly not wish that on New York, New Jersey or here, but I think there are some benefits that we can gain from it.

Greg Dalton: So we'll get into that, Sandy as a lesson and as a wake-up call. Ezra Rapport, you've focused a lot on seismic risk and that's often been the biggest risk in the Bay Area, and climate has come up recently. So tell us about when you started to realize that climate risk was something that you would deal with in your career, not something that your successors or future generations would have to deal with.

Ezra Rapport: Well, we're preparing a sustainable community strategy that will be adopted this year that's supposed to be looking out to 2040. And when we started to get more into the issues of vulnerable areas and vulnerable populations, it became apparent to us that we're gonna have to make some significant infrastructure planning before we proceed with that plan. We're going to be adopting a plan knowing that there's a lot of work left to be done, but at least we'll set a schedule forth when we'll hold ourselves accountable for getting the work done.

Greg Dalton: Let's talk about those vulnerabilities. If we look around the Bay Area, what are the biggest risks? What communities, what areas are at most at risk?

Ezra Rapport: The areas that are most at risk are the ones obviously that have the lowest elevation and also the major infrastructure that the Bay Area could see damaged, which would affect everybody. There also is a tremendous seismic risk which is a potential immediate concern and affects how sea level rise is dealt with because of liquefaction within the areas of levies and things of that hard engineering protection would have to be taken into account. So our view is that the assessment, the risk assessment that's necessary for the Bay Area is the first order of business. And we have not done a good one to date.

Greg Dalton: So we don't know? I mean, if you're near the water and flatlands, you're probably ought to be thinking about this, but it sounds like no comprehensive risk assessment has been done. Is that -- did I hear that correctly? Zack Wasserman?

Zack Wasserman: I think that's correct, although we're making small progress towards that. One of the BCDC projects is Adapting to Rising Tides, the ART Project. And it has studied the area along the Alameda County coastline for the Bay, from Albany down to Hayward, and there is a vulnerability assessment. It's on our website. So we've started that. We think it's gonna be -- that kind of approach is going to be used in other parts of the bay. But the next big step is one that really hasn't been taken, although certainly we've given a thought, and that is what can we do to protect our built environment in the most vulnerable areas and our most vulnerable communities.

Greg Dalton: Melanie Nutter?

Melanie Nutter: Well, the California Energy Commission did recently do a study on the Bay Area and some of what they projected was that we could see sea level rise up to 15 inches by 2050 and up to 55 inches by the end of the century. There also were projections saying that we could see increases in temperature in the Bay Area anywhere from 3 to 11 degrees, but as we heard in the last panel, that science is constantly changing and some of the science that's coming out is potentially conservative. So what Ezra said, I think, is exactly true. We as a city don't yet have an agreed upon risk scenario that we have said this is the risk scenario that we are accepting of a baseline and where we will start from. So there are certainly many projections out there, none of them very positive and it could be that they're more conservative than what we'll be seeing.

Greg Dalton: Right. Climate scientists are often very conservative, things that often end up more serious than the scientists admit, so what's the holdup? Why isn't -- why don't we know this is coming up 25 years since climate really came on the national radar.

What's preventing the area from having a risk assessment? Is it the perception that this is something that's decades away, we got time to plan for this? Is it sort of a time scale? Zack Wasserman?

Zack Wasserman: I think there are a couple of factors. Timescale certainly plays into it. But the other factor is that we are a very diverse region with 9 counties, 101 cities, I think that's the number, a whole range of special districts that are involved, and there is no one dominant player in New York, in Chicago and some other areas where they have made some significant progress, although they don't have the solutions yet. There is a dominant player and they can help to organize. Even in San Diego, a region we're starting to communicate and cooperate with, there's a little bit more dominance, but there's a real problem with coordinating all of the efforts in a regional, cohesive and coherent way.

Greg Dalton: So when you say dominant player, does that mean it was kind of a climate authority in New York? There's a new agency that's supposed to kind of get its arms around this? Is that --

Zack Wasserman: Well, I'm sure there are some city members from other boroughs in New York and elements in New Jersey would argue with this. The city of New York itself and the mayor of New York, particularly the current mayor, plays a very dominant role. We don't have that and that's no criticism of any mayor in office today.

Greg Dalton: So it's an individual, not a government entity? Okay. Okay.

Zack Wasserman: Well, it's the two. I mean, we are a more diverse region than almost any similar region in the country.

Greg Dalton: Okay. I think some people in New York might take issue with that but --

Zack Wasserman: Diverse in governance. In governance.

Greg Dalton: Okay. So it takes -- so centralization, if there's a strong political figure, strong agency, those regions are further along, and here, we're fractured because there's a whole alphabet soup of agencies and political figures that can agree. Is that --

Zack Wasserman: Well, it's not that they can't agree, but they have different issues and different perceptions, and I want to be very clear, I'm not arguing that we should seek to make one of the cities dominant. That's not going to happen. It shouldn't happen.

We're trying to make some progress through the joint policy committee set up by the state government, but the joint policy committee has made strides that consist of the four major regional agencies, but it does not have any direct power. We're gonna have to figure out how to do this together by talking and working more closely together on a voluntary basis.

Greg Dalton: Melanie Nutter, when Gavin Newsom was mayor of San Francisco, he often was very vocal, a very visible, somewhat visionary on this issue out front, and drove lots of progress and innovation. That's not happening under Mayor Lee and there's no one quite like that, although Chuck Reed in San Jose might try to take that mantle right now, but we don't have someone who's really banging this drum every day all the time. Is that fair?

Melanie Nutter: Well, I would say, under Gavin Newsom, one of the efforts that he did work to start was coordinating city agencies around adaptation a couple of years ago. And what had happened was because this issue was so new, really the coordination effort stopped and stalled around there not being an agreed-upon risk scenario. Now, fast forward to a couple of years later and a number of city agencies ranging from the municipal transportation agency, to the court, to the San Francisco airport, all have started to do their own studies and really look at assets that are going to be threatened from sea level rise and other impacts from climate change. So now, there really is an opportunity and I think a political will among those working at that level to come together and restart this process.

As it relates to the current mayor and really, current priorities and really where the opportunity is, as you know, Mayor Lee is very invested in our infrastructure and in seeing strong infrastructure investments in San Francisco. And having just been in Washington last week, that was also echoed at the federal level. It's investments and infrastructure and thinking about that as a job creator is also really an opportunity for us to have the discussion around adaptation, even if we're not talking about climate change.

We're really talking about shoring up our assets and ensuring that those are protected and resilient. So there is really an opportunity through the infrastructure priority that we have locally and federally right now.

Greg Dalton: And that's the way to de-politicize it in some ways because climate is contentious polarizing issue in many parts of the country and even parts of the Bay Area. Ezra, let's ask you about the political leadership and whether you were seeing the right kind of -- your organization is association of political leaders. Is there really enough drive in leadership happening on this issue right now or do members sort of think, "Well, I got some time. I may not be in office when this happens. So I'll focus on something else that's gonna help me get reelected."

Ezra Rapport: We're a voluntary association of the 101 cities and 9 counties. And I think almost all of our elected officials realize that this is a regional problem. It can't be solved by any one city or one county. All of the infrastructure interconnects counties, it connects jurisdictions. So they're really looking for leadership at a higher level and I think the region is the first line of defense in terms of trying to figure out how to state this problem and identify the targets that would need to attack, but one of the conundrums about this problem is that the goalpost keeps moving. Even if you get to 2050 or 2100, the problem doesn't end there. So you're continually looking at how do you face more and more infrastructure in at a reasonable cost and lesser time period for making these investments, not to mention that we don't have the financing vehicles to even think about how to do the investments.

Greg Dalton: And you say there that the state's not really a player yet. Do you think that Sacramento needs to do more, to give more authority, to give more dollars for the Bay Area to do that kind of planning and investing it needs to do?

Ezra Rapport: It's a local, regional, state, and federal government responsibility to figure out how to come up with a planning model that is efficient enough to begin thinking about engineering investments. No one wants to invest too much in advance of the problem and no one wants to under plan.

Greg Dalton: Sacramento, just getting its own fiscal house in order. They've been taking money from regions rather than giving money back to them. So how's that gonna play out in terms of Sacramento doesn't have much money to make these kinds of investments.

Ezra Rapport: Well, we've been in a financial crisis for, you know, most of my career here and I think, at some point, you have to hit bottom, you start coming back and I believe we're at that point and so that's when more advanced planning can take place. And you see some significant initiatives in the delta. We have more attention from state agencies now for this problem than we ever had before and the state legislature passes a sustainable community strategy which I think, in the context of looking at long-term development, would incorporate these kinds of issues. So I don't think we're completely behind the eight ball. I think we have strong support from the state and I think, to some extent, the national government. They are -- their Army Corps of Engineers was working in the South Bay which is the most vulnerable area and probably the most high -- most productive in terms of its economic impact and I think the concepts of combining environmentalism with levies and hard engineering is the right approach, and they're six years into it now.

Greg Dalton: Zack Wasserman, let's ask you if you see -- you're part of a state agency that's focused on a region. Do you see more funding coming from Sacramento to address these issues?

Zack Wasserman: I do not see a flood of funding coming, but I do think that we're gonna have tides flowing back and forth and the governor has certainly made -- addressing climate change both in terms of greenhouse gas emission but also resiliency and adaption to protect the built environment one of his priorities.

So I do think we're going to see some efforts. We're working with a set of regions, San Diego, Los Angeles, Sacramento and the Bay Area, working very closely with the governor's office and Office of Planning and Research. So they are engaged. How quickly and how much funding we can get, I am not sure, but we'll get some.

Greg Dalton: Do you agree with what Ezra said earlier about the idea that when times are good, you should really go for it because state budget cycles go through good times and bad, and when times are good, basically grab as much money as you can because it won't last. He didn't say it quite like that. I'm paraphrasing.

Zack Wasserman: Yeah, I'm not sure that's what he said, but I think we need to have a more sustained and careful and thoughtful effort at all of this. I mean, part of what BCDC is doing, along with others, the joint policy committee and others, is really trying to do a longer range campaign. I talk about it as a five- or ten-year campaign to figure out what we need to do to protect our built environment, what we should do to the extent we can think about unintended consequences and, third, how we're gonna pay for it. And certainly, getting more money when there is more money makes sense, but we've got to figure out how to do that on a sustained basis.

Greg Dalton: On funding, you know, there's mitigation which is sort of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, our contribution to the problem and then there's adaptation which is dealing with the consequences. On the global warming stage, what San Francisco, in fact, even with California and the United States does, doesn't really -- isn't gonna really bend the curve. So why not just put all our money on adaptation, which is what we can control, rather than trying to cut our greenhouse gases which isn't really gonna affect the problem?

Zack Wasserman: I'm not so sure I agree that what happens in California doesn't affect the curve. You're right. Our portion of contribution to greenhouse gas is such that if we were 100 percent successful at reducing, it would not control the greenhouse gas problem. However, California is absolutely looked at as a leader in this issue and I think what we do does have benefit in terms of being replicated in and modeled in other parts of the country and indeed the world.

So I don't think it's neither -- we cannot deal with it as an either/or. We have to deal with it comprehensibly.

Greg Dalton: Melanie Nutter?

Melanie Nutter: I agree with Zack. I think it has to be a dual approach of continuing to focus on mitigation as well as having intelligent adaptation at the local level, and the city and county of San Francisco has had a climate program for about five years and we really have been predominantly focused on mitigation measures that we really have seen make a huge impact. So right now, the climate program, as well as some actions that come before that, have helped us to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions in the city by 14.5% below 1990 levels, which is double the Kyoto Protocol and is significant when you look at what other U.S. cities have done. So that is gonna continue to be an area where Mayor Lee is certainly championing many of our green building measures. We know that, in San Francisco, the built environment alone is responsible for 53% of our greenhouse gas emissions and transportation itself is responsible for about 40%. So we know that if we have strong policies and programs in those two areas, we can continue to really reduce our carbon emissions and to mitigate. But we do know, even if we stopped and we're able to mitigate everything today, we cannot ward off every possible impact of climate change. So that's why cities now are waking up to say we do need to adapt as well, so we have to have a dual approach that continues to mitigate and not just accept the fact that we are emitting greenhouse gas emissions and adapting to make us more resilient.

Zack Wasserman: There's one other way that they're really related. California is a leader in this sort of carbon cap and trade program that's generating money. A lot of that money is going to get mitigation measures. Some of that money can go to adaptation measures.

Greg Dalton: Right. And there's also a premise here. Certainly, one of the lessons from Sandy, Hurricane Sandy back east was that the federal government will be there to bail out the states. Is the Bay Area counting on Uncle Sam to bail us out if it gets really bad?

Ezra Rapport: Well, that's the operating assumption, but I think most of us who are in the profession feel that that's a risky proposition, that we're far better off thinking about how to mitigate damage rather than choose the federal government as an insurance company where they're gonna eventually get tired of bailing out coastal cities from these disasters.

Greg Dalton: And FEMA's been bankrupt a couple of times already, right? So --

Ezra Rapport: FEMA operates by annual appropriations. So when there's a disaster, there's an action by Congress that funds it. And the East Coast just got $60 billion for Sandy. What happens if we have an earthquake here where our damage is twice as much? Will we get that kind of appropriation? That's just a guess. So we're far better off trying to figure out how to retrofit our built environment before we need that money and then show what we can do in a local match. I'm not so optimistic that the U.S. government can continue to fund fixing areas just to see them in the same level of risk as they were before. And I think you need a recovery plan that's gonna demonstrate how that risk gets mitigated.

Greg Dalton: And it was a big fight. New York and New Jersey almost didn't get that money. It was really a tough fight back there even with some very strong Republican members of Congress and they're fighting for it. It almost didn't happen. So let's talk about other funding mechanisms for this. If the federal government is not gonna be there, are they gonna at least invest in preventative measures to make their future vulnerability less so that if they do get asked for a handout, that they're gonna be asked for a small handout?

Ezra Rapport: That would be the rational approach. It's the fund hazard mitigation --

Greg Dalton: Well, you just used Washington and rational in the same sentence?

Ezra Rapport: Yes, because if we do not take a rational approach to this problem, we are all facing really catastrophic impacts and particularly the Bay Area because it is a coastal city. It's gonna be facing sea level rise as a very serious problem along with liquefaction and an earthquake. So we have a lot to take care of here. And if we're going to convince Washington that they should provide more hazard mitigation money to reduce the ultimate cost in the long run, then that's, I think, a good strategy. The second part is to recognize that the Bay Area is a huge fiscal generator to the U.S. government and taxes as well as to the state, and provides a lot of the innovative engineering that fuels our defense department as well as many of our other industrial processes. So losing the golden goose would a gigantic loss for the federal government and the state government and we need some money for planning and hazard mitigation.

Greg Dalton: And so where should that money be spent to protect this goose? Obviously, Silicon Valley is a big -- as you said, jobs, economic engine. Let's protect that goose. What should be done to protect that goose?

Ezra Rapport: Well, that's what the Army Corps of Engineers is working on with the many jurisdictions in the South Bay is to look at a combination of strategies that, even within the context of seismic risk, could protect the South Bay for the next 30, 50 years.

Greg Dalton: Zack Wasserman, I've seen, there's a BCDC map that has the headquarters of a lot of technology companies and the inundations with rising sea level rise and Oracle, Google, Apple, et cetera, all those iconic companies are at or in the water.

Zack Wasserman: Yes.

Greg Dalton: So what's gonna be done about, you know --

Zack Wasserman: Well, the --

Greg Dalton: -- preventing that from happening. I imagine that can't be very good for business when the Oracle parking garage is under water.

Zack Wasserman: It most certainly would not be. At the moment, the most specific and aggressive action is what Ezra talked about, the South Bay effort with the marshes and adaptive studies, and Senator Feinstein has been very helpful there. The technology companies down there are starting to engage. They are -- I don't want to say they've had their head in the sand -- they're starting to engage. They do not yet have the sense of urgency that I and others think they need.

Greg Dalton: So they can move, whether they're focused on quarterly earnings, first of all, and this is something that could be decades. And so even the CEO thinking, "I may not be around then," but can't they just move at some point at the cost of doing business?

Zack Wasserman: Well, the abstract answer is yes. But the more concrete answer is those technology companies are located in Silicon Valley and to some extent in San Francisco and to some extent in the East Bay because the human talent pool that is critical to their success is located there.

Greg Dalton: Yeah. I understand they kind of move up the hill towards 280, away from 101.

Zack Wasserman: Well, sure. But moving the kind of facilities that they have is not easy. It makes much more sense for them to engage very heavily and utilize both their creativity as well as some of their capital in working with the Army Corps, with Noah, with BCDC, in terms of developing innovative, natural sensitive solutions and protections.

Greg Dalton: Ezra Rapport? The tech companies engaging starting to realize -- I mean, very logical for them to say, "Redwood City, you want us to stay? Pay to protect us."

Ezra Rapport: I think the assumption there is that we can't rely too much on the private sector to do the protection that government has traditionally provided and the coastal conservancy in California, the Army Corps, BCDC and a whole variety of other jurisdictions are hard at work informing these companies what's happening, but not relying on them to be the entity that pays for it.

Ultimately, what the Army Corps will do once it finishes its report is ask for a federal appropriation for support and then we'll see what other kind of matching funds are required to make it happen.

Greg Dalton: So ultimately, this is gonna cost us a lot of money, somebody a lot of money. I mean, I keep hearing federal state appropriation that this is gonna cost. Melanie Nutter, where is this money gonna come from?

Melanie Nutter: Well, one of their idea is an infrastructure bank and this is something that there's a green infrastructure bank, senate bill that was just introduced last month and the details are really still being worked out. But some folks are looking at this idea of an infrastructure bank either at the state and/or federal level as a way to engage private entities and private industry, and helping to support some of the adaptation measures. So although the details are still being worked out, this concept of having that kind of infrastructure set up at the state and federal level could be an opportunity for financing.

Greg Dalton: And so this is government money that would go in and try to sort of jumpstart this bank?

Melanie Nutter: And leverage with private dollars as well.

Greg Dalton: Okay. And so that, for example, could help protect Silicon Valley or do other things like that?

Melanie Nutter: Potentially.

Greg Dalton: Okay. Zack Wasserman?

Zack Wasserman: This region has also been fairly forward thinking and generous in supporting regional taxes for infrastructure, and that's not -- it's some -- you can't pile everything on that. But in terms of looking forward --

Greg Dalton: To pay for the Bay Bridge, for example.

Zack Wasserman: Pay for the Bay Bridge, exactly. And the regional bonds that were passed are paying for transportation infrastructure throughout the whole area. So I think there is some hope if we can come up with sensible approaches and the education campaign that demonstrates how necessary these expenditures are going to be.

Greg Dalton: So Save the Bay is an organization that wants to have a parcel tax around the bay. I don't know if it's all nine counties. The idea to basically pay for some bumpers around the bay, wetlands, et cetera, is that a viable model where the Bay Area said, "Well, someone in San Francisco is gonna say, 'Well, yeah, I guess we all have to do this,' and I'm gonna pay to protect San Francisco and also, Alameda, Richmond and San Mateo."

Zack Wasserman: I think it is a viable model, particularly in the sense, as I said before, whatever we do, we need to think about unintended consequences. You put a seawall up here, it may only divert the water to the other sides. That may not be the correct solution. We've got to think regionally about that. Whether the parcel tax that the Save the Bay is advocating at the moment is sensible, I'm not sure. I have a little bit of concern that we needed as part of a comprehensive plan that we don't have it yet. On the other hand, you've got of horse and cart problem, and where you decide to move is always one of the [cross talk].

Greg Dalton: Melanie Nutter.

Melanie Nutter: So I would say also, at the local level, we do have that capital planning process and there is a 10-year capital plan for the city and county of San Francisco where many of the dollars that are designated in that capital plan, millions of dollars, are specifically designated towards infrastructure. And it's really an opportunity to open up the discussion at the local level about, through bond measures and other money that is raised locally, specifically through bonds to support capital infrastructure, how can we include any of the adaptation measures that come out of our local and regional work to fund in that way. So I think it's really, as I think Ezra said, it's about local, regional, state and federal dollars coming to an area to really support resilient infrastructure.

Greg Dalton: And one of the big ticket items is SFO and Oakland, and people look at SFO and there was a huge fight to add additional runway some years ago, it seems like that. No one's talking about that these days. And I've talked to some engineers who say, "Well, if you just build -- you know, you build a seawall around SFO, you effectively shorten the runways.

So how is San Francisco gonna, Melanie Nutter, protect SFO?

Melanie Nutter: So SFO along with a number of other city agencies are undergoing a number of studies and assessments to decide what to do. I wouldn't say that we have the answer in a number of cases. So, for instance, the Municipal Transportation Agency is doing an adaptation plan right now looking at our trends at resources, our transit stops, well, all of our buses and our trains restored, our underground railways, how are those going to be effected by sea level rise? So they're coming out with an adaptation plan in about six months, looking particularly at their resources. The San Francisco Public Utilities Commission has really been a leader at the local level on looking at adaptation. About five years ago, they helped to start the water utility climate alliance which is working with other water utilities around the country, looking at how sea level rise, temperature changes will impact our waste water system as well as our water supply. So they're, right now, doing continued assessment about what will need to be done. Same with SFO. So they're looking at different types of reinforcement of whether it's a berm or a seawall and where will that money come from, and how does that affect the operations and the service of the airport. I think there's a lot of questions, but the good news is the work is being done. The challenging news is where will that funding come from and what are the answers gonna be to ensure that we can really address the impacts.

Greg Dalton: Is it possible that San Francisco could ask its neighbors to foot the bill for something -- for a regional facility like SFO?

Melanie Nutter: That's certainly potential. I mean, because obviously SFO does serve at the region. It is something that I'm sure SFO will look at once we know what those solutions are, trying to figure out how to get those funded potentially in a regional way.

Greg Dalton: Ezra Rapport, let's get you in on protecting Oakland and San Francisco airport. So obviously, big drivers for the regional economy, they're at sea level. You know, the idea of -- already, I think Oakland floods sometimes the runways. What's gonna be done there?

Ezra Rapport: Well, I don't think anybody has a specific plan. You know, obviously, they need to elevate. I don't think they can build seawalls and fly over those. But we'll have to wait and see, you know, what that cost is. That's the cost of aviation in the Bay Area if we get into these rising tides within a specific time period and that's one reason why we can't just constantly think about adapting our way out of this. We really need to get a much stronger voice and statement about mitigating this problem. We need to slow it down. We're not ready for all of these impacts. There's too many to just enumerate here, but it's an extremely serious problem for the entire world. We may not be the first ones to suffer catastrophically, but we are on the list because we're a coastal city. We're gonna be facing these problems.

Greg Dalton: And when something happens in New York or another coastal community around the world, how does the bureaucracies and agencies in the Bay Area respond to that? Do they say, "Well, that's them over there." Is that -- how does it connect to the Bay Area even though the facts might be different?

Ezra Rapport: It definitely connects. Most of the agencies have technical staff. We see these connections and we see an opportunity, too, to advice the public and elected officials that certain steps need to get taken. And we do have a joint policy committee of the four largest regional agencies beginning at the water board, too, but ultimately, we have the resources, the technical resources to help figure out this problem. We need some additional funding for dynamic engineering models and other kinds of scenarios that we know are -- would be very beneficial, but I think we have the skills within these agencies to come forward with a set of plans that can face in how we need to protect the Bay Area.

Greg Dalton: Melanie Nutter, you worked for Speaker Pelosi before this current job.

There's a political messaging challenge here which is to go to people and say more government, more spending is the solution to this problem. How's that gonna play out? Because that's not something politically very popular to go to voters and say, "Well, this thing that you may or may not believe in is happening and the solution is more government, more spending."

Melanie Nutter: You're absolutely right. It is a messaging problem. Again, being back in D.C. and we spoke with Senator Boxer who said the two hot button issues, in the senate particularly as it relates to California, climate change and high speed rail. Those were the two things that sort of get different members of different parties riled up and concerned. But that's, again, going back to infrastructure. That was really seem to be the solution to talk about what we're going to do to support those resources because, it's true, something like climate change now does have a lot of baggage for, you know, people of either party who don't necessarily believe it. But when you're talking about the practical day-to-day of how to support our communities, that's really the lens through which I think we can have that conversation, and again, it goes back also to mitigation and saying we can't just assume that we're gonna go forward with business as usual because we know that that is going to be way too costly and that having mitigation measures in place is actually a less expensive way to go. And so we just really need to talk about it through that lens, I think.

Greg Dalton: So we're gonna rename Climate One to Infrastructure One and [laughter] have conversations and not use that word, but there's a premise that the status quo is cost free. But that's not really the case. There's tremendous cost in the way we're doing now, but it's only those incremental costs, Zack Wasserman, that people look at. They don't look at the cost of the way of business as usual.

Zack Wasserman: You're right. One of the things I would do if I could is I would make everybody, every adult, every student above sixth grade look at the programs on Discovery Channel and Frozen Planet that shows what's happening with the ice sheets because that's the kind of graphic visceral message.

And particularly when you understand that that will not stop even if we reduce greenhouse gases to zero tomorrow. That's the kind of push that I think we need to do, the education. I don't think we can go out and talk to people today about supporting attacks for this infrastructure. I think we need to educate them about the real need, educate them about what we may do as we think about it. There are some boards here for the people in the audience on the designing for Adapting to Rising Tides Project that we did, you know, brought some science fiction, very creative approaches, but some of those are going to have to be explored. When we get those with that education, then I think people will be ready to support us.

Greg Dalton: One of those sort of science fiction approaches is called Goldilocks. The idea of sort of putting a big gate at the mouth of San Francisco Bay and can't we just build a big wall that will protect us and everything will be okay?

Zack Wasserman: I happen to think that ultimately it might be the solution. But I do not think it's one that we're quite ready to adapt today and we don't have the engineering study. But that's -- there's folding waters out there which is essentially that kind of Goldilocks gate.

Greg Dalton: Does that just push the water somewhere else? I mean, it kind of pushed them off --

Zack Wasserman: Well, absolutely. And when I talked earlier about unintended consequences, in addition to the deciding whether we can really engineer that kind of solution or there's another one out there for a net that would stop surges, it would stop rising tide. What the effect of that is, on the rest of the coast, when that water is pushed backward, it doesn't come up all the way through into the bay and into the delta.

Greg Dalton: If you're joining us, we're talking about sea level rise and adaptation in the San Francisco Bay Area. Our guests are Zack Wasserman, chair of the Bay Conservation and Development Commission. Ezra Rapport -- am I saying that right?

Ezra Rapport: Rapport.

Greg Dalton: Rapport. I knew I wasn't saying it right. Pardon me. Executive Director of the Association of Bay Area Governments. And Melanie Nutter, director of the San Francisco Department of the environment. I'm Greg Dalton. Let's talk about some specific communities that are being built. Former military bases, many of them, Treasure Island, Hunters Point, Alameda, these are areas that the military has left after the Cold War. They're at sea level. We're about to put in a lot of capital, a lot of housing. Is it being done, Zack Wasserman, in a climate smart way with sea level rise in mind?

Zack Wasserman: It will be. We do not have plans before us yet for any of those projects where BCDC has jurisdiction which is either because they're filling the bay to support something or 100 feet inland from the high tide line for purposes of public access. But realistically, anybody who is going to build us new community, particularly a residential community, that is very close to the water line, is gonna have to address those issues. It's a part of marketability. There may be some doubts in some people's minds about whether sea level is going to rise. There's enough certainty that it's going to rise in enough minds even though we don't know the exact range that to expect to be able to sell residential or commercial projects for that matter that are on the water they're gonna have to address that not simply because the regulators, both at the regional level and the individual city level, will require it, but the market will require it.

Greg Dalton: So I understand that the market will be a factor there but also the Bay Conservation and Development Commission tried to put some constraints on developer liability in the future if someone develops Treasure Island, and 15 years from now, Treasure Island is under water, what recourse would a buyer have, what responsibility would developers have if they built something in harm's way when there's a reasonable cost of, "Hey, they should have known?"

Zack Wasserman: Now you're asking me to put my hat on as a real estate lawyer as opposed to my hat as chair of BCDC. But I think the answer is it depends on how well the disclosures are developed both by the developer and their financing sources and the title industry as well as, to some extent, the deregulators, more on the individual city and county jurisdictions than at the regional level.

Greg Dalton: Melanie Nutter, San Francisco is putting billions of dollars in real estate in Mission Bay which is right in the inundation zones or the new UCS hospital. Was that built with sea level rise in mind? Is the power generator in the basement? I don't expect you to know that, but the idea is your Mission Bay is potentially at risk and we're just putting billions of dollars of capital in there.

Melanie Nutter: I think that you have hit on the critical point that we're at for San Francisco. A lot of our high-priority areas, areas that either have been recently built or are slated next for large development are our high-risk areas. So that really has brought home the point to city officials and our elected leaders that if we go forward in a piecemeal fashion, we could end up with a real problem on our hands of development that either took different risk scenarios into account and planned in a way that makes them more vulnerable without having a citywide policy strategy or plan to say this is what we know could be the impacts in the future so we have to plan now. We don't want to do it in an incremental piecemeal fashion. Right now, you know, a number of developers, it's left up to themselves right now to basically go out and do some of the studies and come up with risk scenarios that then, of course, are looked at by the permitting agencies. But we do feel the responsibility as a city to take a more proactive approach to adaptation, especially in these high-priority, high -risk areas.

Greg Dalton: So, Zack Wasserman, would you buy a waterfront condo in Mission Bay?

Zack Wasserman: It depends on my investment timeline scenario.

[Laughter]

Greg Dalton: Right. But it's basically buy or beware at this point.

Zack Wasserman: I think it is buy or beware and I think it will have and some people think it already has, I'm not sure there are statistics to support that, an effect on waterfront property values which used to have a high premium and I suspect today don't have as much of a premium. On the other hand, most people buying a house or, you know, not necessarily thinking what's gonna happen in 25 years, and so they may well be able willing to pay some premium for having that benefit of being approximate to the water, recognizing that, at some point, it's going to go away.

Greg Dalton: Melanie Nutter, how about the Warriors' arena? How's that gonna be built into a fabric or waterfront? Are they taking sea level rise into account, bringing that shiny new arena to the waterfront in San Francisco?

Melanie Nutter: So that is actually a question that we've gotten quite a bit of -- that is a high-profile development right along the waterfront and from my discussions with the Warriors stadium representatives, they are taking that into account, looking at both shoring up the piers that are really in need of repair to be able to shore up that development, as well as having a setback. So they are taking that into account, but the question is, is that development going to be operating under the same risk scenario and then adaptation measures as developments that are anywhere near it and along the waterfront. So where -- as it is being taken into account, again, the question is what is the big picture strategy for the city and other waterfront development.

Greg Dalton: So we'll go forward, but there's still lot to be determined there in terms of how that's going to be built into the city's quadrant.

Melanie Nutter: Exactly. It's definitely on their radar screen, I will tell you that.

Greg Dalton: Ezra Rapport, what are we learning from other cities around the world that have done similar things, San Diego, Vancouver, that have done smart things? I want to get the others in here in terms of other jurisdictions, other regions kind of wrestling similar issues.

Ezra Rapport: Well, I think all the regions are really suffering from the same real estate problem which is what's the residual value of the properties once the 30-year period of financing is over and what can they say about what they'll do to protect properties within inundation zones. So in the absence of an answer, since no one is providing significant infrastructure, it is buy or beware and seek higher elevations. So if you have a major project and you're not thinking about those kinds of elevations, then you're essentially assuming that you can take all the economic value through the financing period. And this was a subject in New Orleans as well as you started looking at was it gonna be coastal restoration to protect the city or were you gonna be facing the same type of problem as it went along. And there's no right answer to it. It has to do with your perception of whether you think that the methods that the city uses or the region uses to protect this high-value infrastructure is gonna success, and if not, then you'll get out of it at a time when you still make your money back.

Greg Dalton: Melanie Nutter, who does San Francisco -- what other cities that San Francisco look to for ideas and inspiration when trying to wrestle with this?

Melanie Nutter: So there's really three North American cities that we've been looking at who are pretty far along on their adaptation planning. New York City, ironically, is one of them. They actually have done quite a bit of work under Mayor Bloomberg's leadership putting together a plan where they really worked through the building codes and through the development process to integrate adaptation.

So that is a very forward-thinking effort. Also Chicago put together a very good adaptation plan, raised about a million dollars both from foundation and other private sources to put together a citywide plan. And Vancouver has also done a lot, not only looking at infrastructure but also resilient communities and neighborhoods, and how some of these climate change impacts will affect people in health. And so Vancouver has done a lot of really good work there, too. Those are three cities.

Greg Dalton: And you mentioned the health. It often gets overlooked in these sorts of things. It tends to be a very property-centric discussion. Disease, there's -- after Sandy, there was talk of mold being a big problem. So, Melanie Nutter, let's talk about the health department and health consequences of a climate-driven event or planning for health protection.

Melanie Nutter: So our department of public health has just gotten a grant from the Center for Disease Control to look at what some of the health impacts would be in our neighborhoods looking at the impacts of climate change. And so that study is currently underway. But we do know that some of the communities, particularly the Bayview neighborhood is at risk both because of where it's located, as well as because of its population. We anticipate that when we have higher temperatures in San Francisco, one projection was that we could go from about 20 extreme heat days in San Francisco to somewhere around 94. That's really going to disproportionally affect vulnerable populations, seniors, young people, low income. It worsens air quality and so people who have respiratory issues, definitely impacts asthma and other types of respiratory problems, and also the fact that we have a population that is not well acclimated to high heat. So one other thing I'll mention is 11 percent of our public housing in the Bay Area has air-conditioning. So when you think of more heat days in the Bay Area, we are simply not prepared to deal with that impact.

Greg Dalton: And is it possible that we could even have cooling centers in San Francisco?

Cooling centers where people go on hot days to shelter and place because they don't have it. I mean, is that something that you think about New York, Chicago having cooling centers but San Francisco with a cooling center?

Melanie Nutter: And again, that could be one of the adaptation measures that we have to look at. We're up to 94 heat days a year. We'll have to have those types of measures in place.

Greg Dalton: Let's bring the audience into the conversation. We're going to put the microphone up here and invite your participation with a comment or question here for our guests at Climate One. And while we do that, I just want to talk -- ask Melanie one more question about Ocean Beach. There's already plans to move the highway on Ocean Beach and actually so that it goes around the zoo. I mean, I'm trying to think of things that are more immediate and concrete that are happening very soon.

Melanie Nutter: Yes. So the Ocean Beach master plan, which a number of agencies and spur have been involved in, really have looked at the erosion. That's currently happening on Ocean Beach and what needs to happen going forward. So those are the types of measures that are being put in place right now. Relocating portions of the great highway and setting back elements of Ocean Beach, that is something that is upon us right now.

Greg Dalton: Let's have our audience question. Welcome to Climate One.

Jeff Butter: Yes. Jeff Butter again. One thing I haven't heard anything about is the fact that the same impacts that the storm had on New York City could very well happen here with a tsunami and that's flooded parks, airport flooding, levies smashed and destroyed, and so it's all part of sea level rise, just a different aspect of it.

Greg Dalton: We haven't mentioned tsunamis yet. So, Ezra Rapport?

Ezra Rapport: Yes. ABAC does do have a mitigation for the region as a whole, and we're not a terrible risk for a tsunami because our earthquake faults are called slip faults and faults that are subduction zones are the ones that cause real tsunamis that they go on top of the prior fault and then they create all this pressure to raise the tide.

So Northern California has some tsunami risk outside of the Bay Area because of the subduction faults up in the Pacific Northwest, but the Bay Area has pretty little tsunami risk.

Greg Dalton: But couldn't the tsunami be triggered at another fault far away? I remember Santa Cruz was impacted at low tide by a tsunami that originated far away in the Pacific.

Ezra Rapport: Right. There will be some potential residual tsunami effect from a subduction zone earthquake far away from the Bay Area.

Greg Dalton: But it still is a small risk?

Ezra Rapport: Yeah. It's nothing like the kind of risk that you saw in other countries --

Greg Dalton: In Japan. Okay.

Ezra Rapport: -- around the world, yeah.

Greg Dalton: Zack Wasserman, anything to add?

Zack Wasserman: No.

Greg Dalton: Okay. Let's have our next question. Welcome to Climate One.

Dan Miller: Yeah, hi. Dan Miller. There was some discussion about 15 inches of sea level rise by mid-century, and maybe 50, 55 at the end. But like many things with climate, it seems that things might happen a lot faster than the early predictions. Climate scientist James Hansen said that he expects under business as usual that we'll see 6 to 16 feet of sea level rise by the end of the century, and as much as three feet by mid-century. How does that affect your plans and do we get to a point where it's actually beyond adaption? And if so, then should maybe the Bay Area focus attention on moving Washington towards some mitigation efforts as well?

Greg Dalton: Melanie Nutter?

Melanie Nutter: Sure. So Department of Environment is currently leading an effort to bring together all of our city agencies to really have a citywide adaptation plan, and the first item on our list is to really come up with a risk scenario that we will accept and use as a city. So, exactly, the numbers that I cited were one study, but there are many different predictions around what could be our impacts.

So that is really -- the first step is, in order for us to have a plan, we need to know what our baseline is and where we're starting from, and I suspect that we will be looking not only at the conservative numbers but really kind of worst case scenario because, as a city, we have to plan for worst case scenario.

Greg Dalton: And isn't it also a challenge that a lot of these models don't distinguish between California and Colorado? They don't give regional policymakers, information in a geographic scope that you need to make decisions for your areas of jurisdiction because there's a mismatch between the climate models which are long periods of time, broad geographies and you need to know something within, you know, much narrower time than geographic zones. Zack Wasserman?

Zack Wasserman: That is a problem. On the other hand, the longest standing tide measurement in the country is at the mouth of the Bay Area, at the Golden Gate Bridge. So many of the broad projections are not necessarily true for us and recently, in the last 30 years, say, the rise here has been a little bit less than in New York for a whole range of complex scientific reasons beyond my ken, but I understand it's real. Nonetheless, we've got a lot of local data, a lot of local studies. However, the best studies, even localized, do have a great deal of uncertainty, the nature of nature and the limits of scientific information. So we do have to project between these ranges, and as planners, we get a little bit caught because we want to work for the most realistic change that we can get our hands around. If we come choose only the worst, we will engender a level of disbelief that I think will hurt what we're really trying to do.

Greg Dalton: And high costs. Melanie Nutter?

Melanie Nutter: One other thing that I'll add is it's going to be critical for our city effort and for a regional effort to think about adaptive management and knowing that even when we do come to a risk scenario that we can all agree upon, we need to know that that is not going to be fixed in time for 20, 30, 40 years. The science will continue to evolve, so we need to set up processes at the local and regional level that will also continue to evolve where we can reevaluate our plans and our scenarios, and be nimble as we continue to do this effort.

Greg Dalton: So an example is the Bay Bridge, beautiful Bay Bridge, but we now we got to raise or defend the on-ramp to that Bay Bridge because sea level rise as a reference doesn't seem to have been taken into effect, into account when that was all seismic, it wasn't sea level rise.

Ezra Rapport: I wouldn't say that entirely, but I think some of the planning that gets done is how long will that effect last, how long do you think the approach of the bridge will be cut off and so there are examples where the kind of risk benefit analysis says that the cost of the infrastructure to protect it is way more expensive than the inconvenience of not having access to the facility or the facility being down. And that's part of the issue here. We're talking about flood control. Hundred years ago, the Bay Area flooded routinely. But even since 1950, we've had 26 flooding events. This is different because the risk is not static. It just continues to climb. And it becomes very difficult to settle on what's an appropriate infrastructure investment. Are you underfunding it, meaning that it's not going to be effective, or are you overfunding it which means your investment is stranded for a substantial length of time? And it paralyzes the process because we haven't faced this type of risk before. At some point, the infrastructure can't handle the sea level rise and you're gonna be looking at a complete change in the way the Bay Area operates.

And what we're trying to advocate for is as strong a mitigation program as possible that can be sent as a message around the world with California as a demonstration project that we really can cut this emissions because people say, even if we stop the emissions today or tomorrow, we still have this problem. But we're nowhere near stopping emissions. We're finding more and more sources of hydrocarbons that's gonna look like they're gonna be cost-effective to burn and it's an extremely worrisome problem, I think, for the globe as a whole.

Greg Dalton: Let's have our next audience question. Welcome.

Male Audience: Hi. I am curious about how robust networks like C40 Cities, these groups of cities are all obviously facing similar challenges. How robust and useful they are to San Francisco, and are there opportunities there when cities act together to do maybe bigger things to confront what obviously is a global problem?

Greg Dalton: Melanie Nutter?

Melanie Nutter: So that is really an area of great hope and I think great progress. Those networks, there's a number of them. One is Green Cities California, which is a network of California sustainability directors. There's the USDN, which is the Urban Sustainability Directors Network which is U.S. and Canada. And then there's C40 which is chaired by Mayor Bloomberg where it's the largest 40 emitting cities around the globe who are all interested in doing climate work. So those networks, in the past two to four years, have been, I think, critical really to accelerating both the mitigation work as well as the adaptation work in cities because now we're in a situation where it isn't every sustainability director working with their mayor and their board of supervisors in a vacuum to create these solutions, and to find policies and programs that work. There's a lot of cross collaboration where there can be replication from one city to another and have much more rapid progress.

So I've been really thrilled and honored to participate in a number of those networks and I think that there's a lot of opportunity for additional progress there by cities working together.

Greg Dalton: And there's even a new exchange I heard about recently, people -- counties sharing adaptation plans, so sharing best practices, using the web so people don't have to do that, sort of recreate it from scratch. Yes. Welcome to climate one. Let's have our next question.

Male Audience: This is somewhat hypothetical because I don't think policy is anywhere near this type of thing but it is sort of a national defense issue. Is it possible that the funding that goes to national defense, maybe in the future, when climate awareness changes, could be applied -- that type of funding could be applied to adaptation or mitigation.

Zack Wasserman: Yes. It's not quite on the, pardon the pun, front lines now. But there have been some discussions starting with national security of national defense that it is a part of their issue as well and there may be funding available there.

Ezra Rapport: And the National Security Agency rated the risk to the delta as the number one risk to the U.S. economy. So it has registered at that level and I would expect that, as time goes on and we see more catastrophic damage probably in the East Coast where there's subject of storm surges, that we're gonna have more and more dialogue about what is really important for the U.S. economy.

Greg Dalton: Did you say the National Security Agency rated the risk to the delta as the biggest economic threat to the United States? That's really interesting.

Ezra Rapport: Yes. That's what I heard when I was in New Orleans.

Greg Dalton: I will say that I interviewed thesSecretary of the Navy who talked about a warming world and he actually said that they need more ships, more money for the navy and more ships to patrol the warming arctic because there's more sea now for them to patrol up there.

So they certainly don't see a warming world as reducing their budgets. They see it as increasing their budgets. Let's wrap up by asking you to sort of look into your crystal ball. We talked about some -- a lot about risk management, et cetera. What's the Bay Area gonna look like. How are we gonna respond to this? If you look 20 or 30 years out, Zack Wasserman, are we gonna be in a fundamentally different Bay Area where we have a different relationship with the water that we love so much, jogging, living near the water to what brought us here, are we gonna have a different relationship?

Zack Wasserman: I don't think it'll be fundamentally different. I think, in some areas, it may certainly be different. There are some pads along the dikes in the delta that you're not gonna be able to move on, so there will be some changes according to that. There may be new pads created because one of the things that we're trying to do and that the Save the Bay initiative is really aimed at is creating tidal marshes and others that can help mitigate against both surges, and rising tide that will take away some areas to get to the water will create new ones. So we're dealing with a changing bay. We're close to the end of a new strategic plan for the BCDC that is very much looking at those issues. But I don't think it's going to -- in a 10- to 20-year framework, I don't think it's gonna be critically different. If you ask me for a 30- to 50-year framework, it might be.

Greg Dalton: Melanie Nutter, a lot of tourists come to San Francisco for its charm, it's waterfront. How do you think it's gonna change in that couple of decades and then further out?

Melanie Nutter: Well, I think it's certainly going to impact our development areas. So, you know, the hope is that, because we're starting now, that adaptation measures as well as mitigation measures will be integrated into our larger developments that will be coming online in the next 10, 20, 30 years. I think, in the longer run, looking at the entire bay, one of the things that we didn't talk too much about today is wetlands restoration and really using our natural habitat as another adaptive measure because I think we do, you know, tend towards talking a lot about infrastructure because there certainly is a lot of engineering that we could do to mitigate and adapt to these impacts, but I think in the long run, we will have a bay that both has infrastructure where needed but also investments in things like wetlands restoration and additional natural areas that could help us to adapt.

So I think that that's something that we will see hopefully in the long term.

Greg Dalton: One of the big recommendations coming out of Hurricane Sandy in New York, New Jersey was the Army Corps of Engineers saying more wetlands at that sort of dollar for dollar, that's money well spent, and all sorts of ecological and asset protection, property protection ways is those wetland restoration. Ezra Rapport, a couple of decades out, the Bay Area is gonna be kind of the same or gonna be very different?

Ezra Rapport: A couple of decades out, probably pretty much the same outside of the South Bay, which I think will be protected.

Greg Dalton: Well, you think the South Bay will see the most changes or the most --

Ezra Rapport: I think the South Bay has an urgent need for protection and I think the people who are studying it are on the job and there will be a federal appropriation to support protecting portions of the South Bay. I think they are finding that the bay restoration -- the wetland restoration is an important mitigating factor to reduce the amount of engineering that's required for the seawall. So therefore, it's a compatible concept and makes sense in terms of the ultimate savings. I would say, from looking at that work, that there's probably a 20-year lead time before any significant infrastructure can take place because of the complexity of the environmental studies that are required and the need for an overall scheme for the levels of protection or the timeframes under which we're willing to accept these types of investments.

Greg Dalton: So we have enough time but we better start now.

Zack Wasserman: Amen.

Greg Dalton: And on that note, we better end it here. Our guests today at climate have been Melanie Nutter, director of San Francisco Department of the Environment; Ezra Rapport, executive director at the Association of Bay Area Governments; and Zack Wasserman, chair of the Bay Conservation and Development Commission. I'm Greg Dalton. Thank you, all, for coming to Climate One today.

[Applause]